Killing Socrates

Or, On The Willful Destruction Of Gardens Of Collaborative Inquiry

One of the more interesting dynamics of the past eight-or-so years has been watching a bunch of the people who [taught me my values] and [served as my early role models] and [were presented to me as paragons of cultural virtue] going off the deep end.

Those people believed a bunch of stuff, and they injected a bunch of that stuff into me, in the early days of my life when I absorbed it uncritically, and as they’ve turned out to be wrong and misguided and confused in two or three dozen ways, I’ve found myself wondering what else they were wrong about.

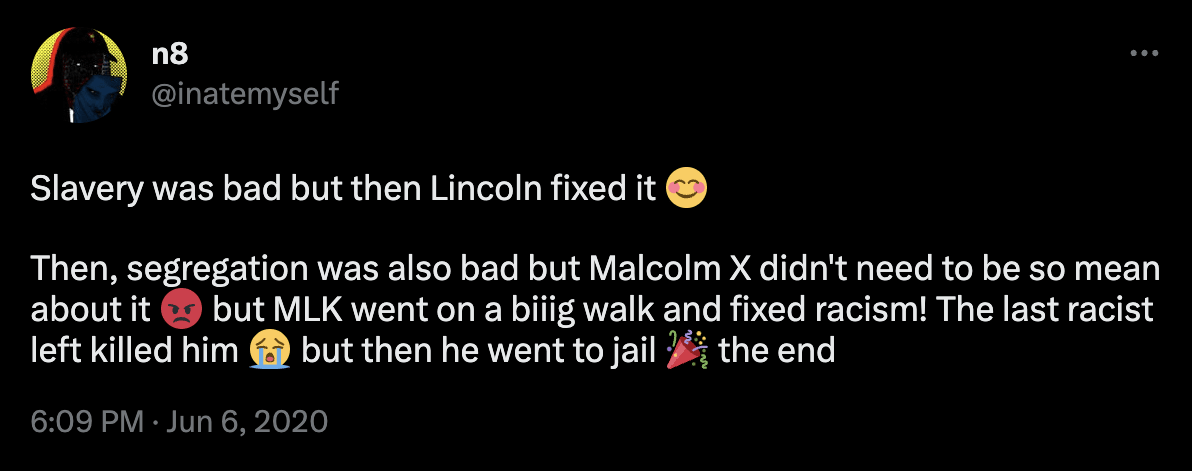

One of the things that I absorbed via osmosis and never questioned (until recently) was the Hero Myth of Socrates, who boldly stood up against the tyrannical, dogmatic power structure and was unjustly murdered for it. I’ve spent most of my life knowing that Socrates obviously got a raw deal, just like I spent most of my life knowing that

It now seems quite plausible to me that Socrates was, in fact, correctly responded-to by the Athenians of his time, and that the mythologized version of his story I grew up with belongs in the same category as Washington’s cherry tree or Pocahontas’s enthusiastic embrace of the white settlers of Virginia.

The following borrows generously from, and is essentially an embellishment of, this comment by @Vaniver.

Imagine that you are an ancient Athenian, responsible for some important institution, and that you have a strong belief that the overall survival of your society is contingent on a reliable, common-knowledge buy-in of Athenian institutions generally, i.e. that your society cannot function unless its members believe that it does function.

This would not be a ridiculous belief! We have seen, in the modern era, how quickly things go south when faith in a bank (or in the financial system as a whole) evaporates. We know what happens when people stop believing that the police or the courts are on their side. Regimes (or entire nations) fall when their constituents stop propping up the myth of those regimes. Much of civilization is shared participation in self-fulfilling prophecies like “this little scrap of green paper holds value.”

And if you buy

“My society’s survival depends upon people’s faith in its institutions.”

...then it’s only a small step from there to something like:

“My society’s survival depends upon a status-allocation structure whereby [the people who pour their time and effort into building things larger than themselves] receive lots of credit and reward, and [the people who contribute little, and sit back idly criticizing] receive correspondingly less.”

People follow incentives, after all. If you want them to contribute, you need them to believe that there is something worth contributing to, and that they will benefit from doing so. If you fail to incentivize the hard work of creation and maintenance, or if you equally incentivize the much easier work of armchair quarterbacking, you will predictably see more and more people abandoning the former for the latter.

From this perspective, Socrates looks much less like a hero whose sharp wit punctured the inflated egos of various Athenian Ayn Rand villains, and much more like someone who found a clever exploit in the system, siphoning status without making a corresponding contribution.

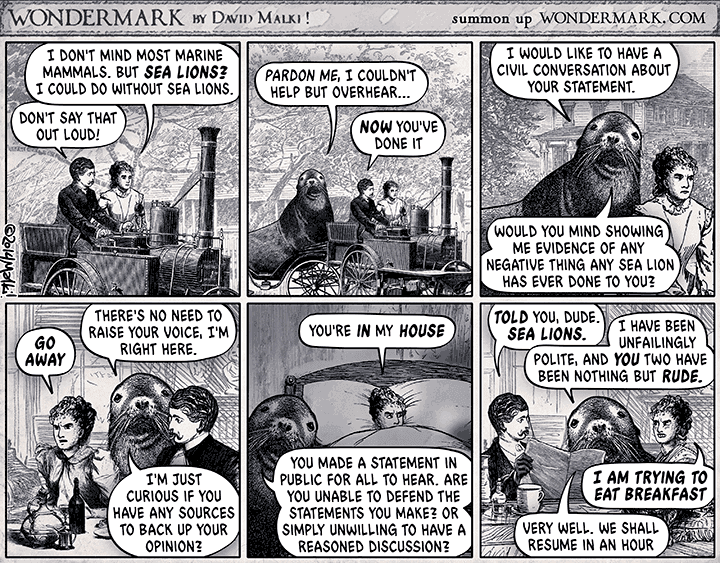

By adopting a set of tactics wherein one can win any fight by only attacking and never defending, one can place immense burdens on any positive action (“Oh, so this is annoying? How would you define annoying?”) while not accepting any burdens of their own (“I’m just asking questions!”). One of Socrates’s innovations was a sort of shamelessness—if someone responded to him with “only a fool doesn’t understand what ‘annoying’ means!” he was happy to reply with “Indeed, I am a fool! So, can you explain it to me?”

This is not, in fact, a cooperative act. It is creating a burden—of explanation, of clarification, of interpretive and pedagogical labor—and then displacing that burden onto the other person. It’s increasing the cost of contributing to intellectual progress, and thereby discouraging people from trying to contribute.

It is indeed important and valuable to have one or two Socrati around, just as it’s important and valuable to have one or two court jesters who are willing to speak truth to power.

But Socrates—as affirmed by the majority vote of some 500 Athenians who convicted him—was corrupting the youth, i.e. setting an example which many of Athens’ young people were emulating.

If it looks like a substantial fraction of an entire generation wants to grow up to be jesters instead of kings or knights or counsellors, then the bedrock upon which the polis rests—the collective self-fulfilling prophecy—crumbles. A thousand hole-pokers will rapidly tear the social fabric to shreds. This is an existential threat, to which the Athenians (plausibly) responded proportionately!

It’s worth noting at least three other relevant things:

The preceding decade had contained a military defeat, a puppet government installed by the conquerors, a coup, a counter-coup, and a counter-counter coup; things in Athens were actually unstable, and it’s not difficult to be sympathetic to the view that this was the wrong time to be picking nits.

During the trial itself, Socrates remained committed to the bit, wielding the same weaponized disingenuousness that brought him there in the first place.

While the legend I absorbed in childhood holds that he was “murdered for telling the truth,” most accounts show that he was allowed to propose his own punishment, and suggested that the state “punish” him by providing him with free food and housing as payment for noble service rendered. When the state replied with “how about death, instead?” Socrates basically responded “if you kill me, all those youth I’ve corrupted are gonna keep on doing exactly the same thing I taught them to do,” which, again, sounds very hero-spitting-in-the-villain’s-eye if you’ve predecided that you know who the good guys are, and less so if you have not.

More directly quoting the comment from which the above descends:

A few years ago, it seemed to me like one of the big problems with LessWrong was that the generativity and selectivity were unbalanced. There wasn’t much new material posted on LW, and various commenters said “well, the thing we should do is be even harsher to authors, so that they produce better stuff!”, and when I went around asking the authors what it would take for them to write more on LW, they said “well, putting up with harsh comments is a huge drawback to posting on LW, so I don’t.”

Now, it would have been one thing if it were the top writers criticizing things—if, say, Eliezer or Scott or whoever had said “actually, I don’t really want my posts to be seen next to low-quality posts by <authors>” or had been skewering the flaws in those posts/comments. [Indeed, many great Sequences posts begin by quoting a reaction in the comments to a previous post and then dissecting why the reaction is wrong.] But instead, the commenter most frequently complained about by the former authors was a person who did not themselves write posts. [emphasis added]

Now, the specific person I had been thinking of had been around for a long time. In fact, when they first started posting, their comments reminded me of my comments from a few years earlier, and so I marked them as someone to watch. But whereas I acculturated to LW (and I remember uprooting a few deep habits to do so!), I didn’t see it happen with them, and then realized that when I had been around, there had been lots of old LWers to acculturate to, whereas now the ‘typical comment’ was this sort of criticism, instead of the old LW spirit.

“Oh,” I said in a flash of insight. “This is why they executed Socrates.”

If a culture has zero Socrati, then you end up with an emperor strutting naked through the streets, claiming to be wearing robes of the most diaphanous silk.

One Socrates can prevent that. One Socrates can, in fact, call it like it is, and poke holes in things that aren’t sound and defensible, and generally improve the health of the system via a kind of hormetic stress.

But if Socrates sets the vibe—if the youth of Athens decide that the right mode to be in is aggressively critical—if they view this as a noble calling, part of holding everyone else to account—if the percentage of people doing the Socrates thing rises above a pretty small threshold—

There’s only so much withering critique a given builder is interested in receiving (frequently from those who do not themselves even build!) before eventually they will either stop building entirely, or leave to go somewhere where buildery is appreciated, rewarded, and (importantly) defended.

(Someplace where the Socrati do not have concentration of force.)

It’s a dynamic tightly analogous to the Copenhagen Interpretation of Ethics, in which trying at all to help with a problem exposes you to blame and criticism, whereas turning a blind eye leaves you safely among the anonymous and un-attacked masses.

If trying to share any thoughts at all results in a metric ton of critique, criticism, nitpicking, sealioning, and unpredictable demands for rigor—

(Which, if left unanswered, tend to be treated by the Socratic crowd as moderately strong evidence that you were full of shit to begin with, ignoring alternative hypotheses like “maybe that question wasn’t worth the time and effort it would take to deconfuse the asker.”)

—then you will observe what we do, in fact, observe: multiple specific brilliant and talented writers who seem to be “just the type we want on LessWrong” who are oddly unwilling to come anywhere near the site.

(Some of them unwilling to come anywhere near the site anymore, despite the fact that they used to enjoy being here, back when the comment sections were primarily builders offering critique to each other, in an atmosphere of collaboration rather than one of evaluation and judgment.)

Vaniver continues:

There’s a claim I saw and wished I had saved the citation of, where a university professor teaching an ethics class or w/e gets their students to design policies that achieve ends, and finds that the students (especially more ‘woke’ ones) have very sharp critical instincts, can see all of the ways in which policies are unfair or problematic or so on, and then are very reluctant to design policies themselves, and are missing the skills to do anything that they can’t poke holes in (or, indeed, missing the acceptance that sometimes tradeoffs require accepting that the plan will have problems). In creative fields, this is sometimes called the Taste Gap, where doing well is hard in part because you can recognize good work before you can do it, and so the experience of making art is the experience of repeatedly producing disappointing work.

In order to get the anagogic ascent, you need both the criticism of Socrates and the courage to keep on producing disappointing work (and thus a system that rewards those in balanced ways).

Or, to put it another way:

There are a lot of LessWrong commenters who respond to perceived falsehoods with what looks a lot like an elevated sense of threat. “Don’t let that one through! That one’s wrong!”

But many of the actual claims being responded to in this fashion are not powerful snippets of propaganda, or nascent hypnotic suggestions, or psychological Trojan horses. They aren’t the workings of an antagonist. They’re just half-baked ideas, and you can either respond to a half-baked idea by helping to bake it properly...

...or you can shriek “food poisoning!” and throw it in the trash and shout out to everyone else that they need to watch out, someone’s trying to poison everybody.

(Or pointedly interrogate the author on why exactly they chose to bake their idea this way when it’s so clearly inadequate, would you please explain what made you think that this dough was sufficiently risen to be worth serving?)

It’s the difference between, say, writing a 3300-word piece about how one section of someone else’s building is WRONG, and spending 3300 words suggesting a replacement that might solve the perceived problem better, without containing Flaw X or causing Negative Side Effect Y.

The end result of Socrates Unchecked is not, in fact, a bastion of pure reason and untainted truth. That’s a fabricated option, like believing that a ban on price gouging during a disaster will result in the normal amount of gasoline being available at the normal prices.

What happens instead, in practice, is evaporative cooling, as the most sensitive or least-bought-in of [the authors/builders who made your subculture worth participating in in the first place] give up and go elsewhere, marginally increasing the ratio of critics to makers, which makes things marginally less rewarding, which sends the next bunch of builders packing, which worsens the problem further. A steady influx of, say, people worried about AI can slow this process, but not stop or reverse it (especially if the newcomers pick up on the extant vibe and conclude that That’s How We Do Things Around Here).

People like to repeat the phrase “well-kept gardens die by pacifism,” but they also flinch from killing Socrates, when Socrates is busy suffocating every seedling he can find, and draining the joy out of the act of gardening.

I claim this is an error.

Author’s note: These days, my thoughts go onto my substack instead of onto LessWrong. Everything I write becomes free after a week or so, but it’s only paid subscriptions that make it possible for me to write. If you found a coffee’s worth of value in this or any of my other work, please consider signing up to support me; every bill I can pay with writing is a bill I don’t have to pay by doing other stuff instead. I also accept and greatly appreciate one-time donations of any size.

- Banning Said Achmiz (and broader thoughts on moderation) by (22 Aug 2025 23:02 UTC; 253 points)

- We’re losing creators due to our nitpicking culture by (EA Forum; 17 Apr 2023 17:24 UTC; 168 points)

- Voting Results for the 2023 Review by (6 Feb 2025 8:00 UTC; 88 points)

- Moderation notes re: recent Said/Duncan threads by (14 Apr 2023 18:06 UTC; 52 points)

- 's comment on Moderation notes re: recent Said/Duncan threads by (23 Apr 2023 23:41 UTC; 37 points)

- 's comment on Moderation notes re: recent Said/Duncan threads by (23 Apr 2023 23:57 UTC; 27 points)

- Critic Contributions Are Logically Irrelevant by (15 Jul 2025 1:03 UTC; 27 points)

- Summaries of top forum posts (17th − 23rd April 2023) by (EA Forum; 24 Apr 2023 4:13 UTC; 26 points)

- 's comment on Moderation notes re: recent Said/Duncan threads by (14 Apr 2023 19:38 UTC; 23 points)

- Summaries of top forum posts (17th − 23rd April 2023) by (24 Apr 2023 4:13 UTC; 18 points)

- 's comment on Moderation notes re: recent Said/Duncan threads by (15 Apr 2023 16:34 UTC; 15 points)

- 's comment on On “aiming for convergence on truth” by (12 Apr 2023 7:09 UTC; 13 points)

- 's comment on LW Team is adjusting moderation policy by (12 Apr 2023 0:31 UTC; 13 points)

- 's comment on the void by (13 Jun 2025 6:27 UTC; 11 points)

- The LW crossroads of purpose by (27 Apr 2023 19:53 UTC; 11 points)

- 's comment on Banning Said Achmiz (and broader thoughts on moderation) by (23 Aug 2025 6:21 UTC; 8 points)

- 's comment on Moderation notes re: recent Said/Duncan threads by (15 Apr 2023 17:11 UTC; 8 points)

- 's comment on If Clarity Seems Like Death to Them by (5 Jan 2024 18:19 UTC; 3 points)

I think this post was important, and pointing out a very real dynamic. It also seems to have sparked some conversations about moderation on the site, and so feels important as a historical artifact. I don’t know if it should be in the Best Of, but I think something in this reference class should be.