Physicist and dabbler in writing fantasy/science fiction.

Ben

The original post above is making the argument that leaving out the caveats and exceptions and/or exaggerating the point in order to provoke a discussion is dishonest and unhelpful. They use the term “clickbait” to describe that strategy. I think in general usage the word “clickbait” is used in a broader way, to include this strategy but also to include other things.

Of those titles 2 and 3 are clearly not exaggerating anything, so are not doing the thing the OP is complaining about. Number 1 arguably is, the post is a lawyer telling us that his clients often lie to him. You could argue that the title implies that all of them are liars, where in fact it is only many of them, not all.

But, the whole “check the titles” method is slightly flawed anyway. There is a big difference between someone Tweeting something, being challenged on it and saying something like “Oh, I didn’t mean it literally, I was gesturing in a direction. Yes there are important exceptions but I left them out because life is too short.” and someone being challenged on the title of their blog post, and responding “Did you even read the post underneath the title? I addressed that point, didn’t I?”.

My quick thoughts on why this happens.

(1) Time. You get asked to do something. You dont get the full info dump in the meeting so you say yes and go off hopeful that you can find the stuff you need. Other responsibilies mean you dont get around to looking everything up until time has passed. It is at that stage that you realise the hiring process hasnt even been finalised or that even one wrong parameter out of 10 confusing parameters would be bad. But now its mildly awkard to go back and explain this—they gave this to you on Thursday, its now Monday.

(2) Story Noise. When you were told these stories by freinds, they only gave the salient details, not a word for word repeat of everything that was said. But, at the time they experienced it word by word, they didnt know what the story beats were yet. Some of those details were just distractions, but some of them might be semi relevant. I know when i tell stories i simplify, and sometimes people assume specific solutions are possible or desrieble because of details they dont know.

The index by Reporters Without Boarders is primarily about whether a newspaper or reporter can say something without consequences or interference. Things like a competitive media environment seem to be part of the index (The USAs scorecard says “media ownership is highly concentrated, and many of the companies buying American media outlets appear to prioritize profits over public interest journalism”). Its an important thing, but its not the same thing you are talking about.

The second one, from “our world in data”, ultimately comes from this (https://www.v-dem.net/documents/56/methodology.pdf). Their measure includes things like corruption, whether political power or influence is concentrated into a smaller group and effective checks and balances on the use of executive power. It sounds like they should have called it a “democratic health index” or something like that instead of a “freedom-of-expression index”.

The last one is just a survey of what people think should be allowed.

It reminds maybe of Dominic Cummings and Boris Johnson. The Silicon-Valley + Trump combo feels somehow analogous.

One very important consideration is whether they hold values that they believe are universalist, or merely locally appropriate.

For example, a Chinese AI might believe the following: “Confucianist thought is very good for Chinese people living in China. People in other countries can have their own worse philosophies, and that is fine so long as they aren’t doing any harm to China, its people or its interests. Those idiots could probably do better by copying China, but frankly it might be better if they stick to their barbarian ways so that they remain too weak to pose a threat.”

Now, the USA AI thinks: “Democracy is good. Not just for Americans living in America, but also for everyone living anywhere. Even if they never interact ever again with America or its allies the Taliban are still a problem that needs solving. Their ideology needs to be confronted, not just ignored and left to fester.”

The sort of thing America says it stands for is much more appealing to me than a lot of what the Chinese government does. (I like the government being accountable to the people it serves—which of course entails democracy, a free press and so on). But, my impression is that American values are held to be Universal Truths, not uniquely American idiosyncratic features, which makes the possibility of the maximally bad outcome (worldwide domination by a single power) higher.

I agree this is an inefficiency.

Many of your examples are maybe fixed by having a large audience and some randomness as described by Robo.

But some things are more binary. For example when considering job applicants an applicant who won some prestigious award is much higher value that one who didnt. But, their is a person who was the counterfactual ‘second place’ for that award, they are basically as high value as the winner, and no one knows who they are.

Having unstable policy making comes with a lot of disadvantages as well as advantages.

For example, imagine a small poor country somewhere with much of the population living in poverty. Oil is discovered, and a giant multinational approaches the government to seek permission to get the oil. The government offers some kind of deal—tax rates, etc. - but the company still isn’t sure. What if the country’s other political party gets in at the next election? If that happened the oil company might have just sunk a lot of money into refinery’s and roads and drills only to see them all taken away by the new government as part of its mission to “make the multinationals pay their share for our people.” Who knows how much they might take?

What can the multinational company do to protect itself? One answer is to try and find a different country where the opposition parties don’t seem likely to do that. However, its even better to find a dictatorship to work with. If people think a government might turn on a dime, then they won’t enter into certain types of deal with it. Not just companies, but also other countries.

So, whenever a government does turn on a dime, it is gaining some amount of reputation for unpredictability/instability, which isn’t a good reputation to have when trying to make agreements in the future.

Correct.

I used to think this. I was in a café reading cake description and the word “cheese” in the Carrot Cake description for the icing really switched me away. I don’t want a cake with cheese flavor—sounds gross. Only later did I learn Carrot Cake was amazing.

So it has happened at least once.

There was an interesting Astral Codex 10 thing related to this kind of idea: https://www.astralcodexten.com/p/book-review-the-cult-of-smart

Mirroring some of the logic in that post, starting from the assumption that neither you nor anyone you know are in the running for a job, (lets say you are hiring an electrician to fix your house) then do you want the person who is going to do a better job or a worse one?

If you are the parent of a child with some kind of developmental problem that means they have terrible hand-eye coordination, you probably don’t want your child to be a brain surgeon, because you can see that is a bad idea.

You do want your child to have resources, and respect and so on. But what they have, and what they do, can be (at least in principle) decoupled. In other words, I think that using a meritocratic system to decide who does what (the people who are good at something should do it) is uncontroversial. However, using a meritocratic system to decide who gets what might be a lot more controversial. For example, as an extreme case you could consider disability benefit for somebody with a mental handicap to be vaguely against the “who gets what” type of meritocracy.

Personally I am strongly in favor of the “who does what” meritocracy, but am kind of neutral on the “who gets what” one.

Wouldn’t higher liquidity and lower transaction costs sort this out? Say you have some money tied up in “No, Jesus will not return this year”, but you really want to bet on some other thing. If transaction costs were completely zero then, even if you have your entire net worth tied up in “No Jesus” bets you could still go to a bank, point out you have this more-or-less guaranteed payout on the Jesus market, and you want to borrow against it or sell it to the bank. Then you have money now to spend. This would not in any serious way shift the prices of the “Jesus will return” market because that market is of essentially zero size compared to the size of the banks that will be loaning against or buying the “No” bets.

With low enough transaction costs the time value of money is the same across the whole economy, so buying “yes” shares in Jesus would be competing against a load of other equivalent trades in every other part of the economy. I think selling shares for cash would be one of these, you are expecting loads of people to suddenly want to sell assets for cash in the future, so selling your assets for cash now so you can buy more assets later makes sense.

I dont know Ameeican driving laws on this (i live in the UK), but these two.descriptions dont sound mutually incomptabile.

The clockwise rule tells you everything except who goes first. You say thats the first to arrive.

It says “I am socially clueless enough to do random inappropriate things”

In a sense I agree with you, if you are trying to signal something specific, then wearing a suit in an unusual context is probably the wrong way of doing it. But, the social signalling game is exhausting. (I am English, maybe this makes it worse than normal for me). If I am a guest at someone’s house and they offer me food, what am I signalling by saying yes? What if I say no? They didn’t let me buy the next round of drinks, do I try again later or take No for an answer? Are they offering me a lift because they actually don’t mind? How many levels deep do I need to go in trying to work this situation out?

I have known a few people over the years with odd dress preferences (one person really, really liked an Indiana Jones style hat). To me, the hat declared “I know the rules, and I hereby declare no intention of following them. Everyone else here thereby has permission to stop worrying about this tower of imagined formality and relax.” For me that was very nice, creating a more relaxed situation. They tore down the hall of mirrors, and made it easier for me to enjoy myself. I have seen people take other actions with that purpose, clothes are just one way.

Long way of saying, sometimes a good way of asking people to relax is by breaking a few unimportant rules. But, even aside from that, it seems like the OP isn’t trying to do this at all. They have actually just genuinely had enough with the hall of mirrors game and have declared themselves to no longer be playing. Its only socially clueless if you break the rules by mistake. If you know you are breaking them, but just don’t care, it is a different thing. The entire structure of the post makes it clear the OP knows they are breaking the rules.

As a political comparison, Donald Trump didn’t propose putting a “Rivera of the Middle East” in Gaza because he is politically clueless, he did so because he doesn’t care about being politically clued-in and he wants everyone to know it.

A nice post about the NY flat rental market. I found myself wondering, does the position you are arguing against at the beginning actually exist, or it is set up only as a rhetorical thing to kill? What I mean is this:

everything’s priced perfectly, no deals to sniff out, just grab what’s in front of you and call it a day. The invisible hand’s got it all figured out—right?

Do people actually think this way? The argument seems to reduce to “This looks like a bad deal, but if it actually was a bad deal then no one would buy it. Therefore, it can’t be a bad deal and I should buy it.” If there are a population of people out there who think this way then their very existence falsifies the efficient market hypothesis—every business should put some things on the shelf that have no purpose beyond exploiting them. Or, in other words, the market is only going to be as efficient as the customers are discerning. If there are a large number of easy marks in the market then sellers will create new deals and products designed to rip those people off.

Don’t we all know that sinking feeling when we find ourselves trying to buy something (normally in a foreign country) and we realise we are in a market designed to rip us off? First we curse all the fools who came before us and created a rip-off machine. Then, we reluctantly decide just to pay the fee, “get got” and move on with our life because its just too much faff, thereby feeding the very machine we despise (https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/ENBzEkoyvdakz4w5d/out-to-get-you ). Similarly, I at least have felt a feeling of lightness when I go into a situation I expect to look like that, and instead find things that are good.

You have misunderstood me in a couple of places. I think think maybe the diagram is confusing you, or maybe some of the (very weird) simplifying assumptions I made, but I am not sure entirely.

First, when I say “momentum” I mean actual momentum (mass times velocity). I don’t mean kinetic energy.

To highlight the relationship between the two, the total energy of a mass on a spring can be written as: where p is the momentum, m the mass, k the spring strength and x the position (in units where the lowest potential point is at x=0). The first of the two terms in that expression is the kinetic energy (related to the square of the momentum). The second term is the potential energy, related to the square of the position.

I am not treating gravity remotely accurately in my answer, as I am not trying to be exact but illustrative. So, I am pretending that gravity is just a spring. The force on a spring increases with distance, gravity decreases. That is obviously very important for lots of things in real life! But I will continue to ignore it here because it makes the diagrams here simpler, and its best to understand the simple ones first before adding the complexity.

If going to the right increases your potential energy, and the center has 0 potential energy, then being to the left of the origin means you have negative potential energy?

Here, because we are pretending gravity is a spring, potential energy is related to the square of the potion. (). The potential energy is zero when x=0. But it increases in either direction from the middle. Similarly, in the diagram, the kinetic energy is related to the square of the momentum, so we have zero kinetic energy in the vertical middle, but going either upwards or downwards would increase the kinetic energy. As I said, the circles are the energy contours, any two points on the same circle have the same total energy. Over time, our oscillator will just go around and around in its circle, never going up or down in total energy.

If we made gravity more realistic then potential energy would still increase in either direction from the middle (minimum as x=0, increasing in either direction), instead of being x^2 it would be some other equation.

The x-direction is position (x). The y-direction is momentum (p). The energy isn’t shown, but you can implicitly imagine that it is plotted “coming out the page” towards you and that is why their are the circular contour lines.

If you haven’t seen phase space diagrams much before this webpage seems good like a good intro: http://www.acs.psu.edu/drussell/Demos/phase-diagram/phase-nodamp.gif.

I am making a number of simplifying assumptions above, for example I am treating the system as one dimensional (where an orbit actually happens in 2d). Similarly, I am approximating the gravitational field as a spring. Probably much of the confusion comes from me getting a lot of (admittedly important things!) and throwing them out the window to try and focus on other things.

I am not sure that example fully makes sense. If trade is possible then two people with 11 units of resources can get together and do a cost 20 project. That is why companies have shares, they let people chip in so you can make a Suez Canal even if no single person on Earth is rich enough to afford a Suez Canal.

I suppose in extreme cases where everyone is on or near the breadline some of that “Stag Hunt” vs “Rabbit Hunt” stuff could apply.

I agree with you that, if we need to tax something to pay for our government services, then inheritance tax is arguably not a terrible choice.

But a lot of your arguments seem a bit problematic to me. First, as a point of basic practicality, why 100%? Couldn’t most of your aims be achieved with a lesser percentage? That would also smooth out weird edge cases.

There is something fundamentally compelling about the idea that every generation should start fresh, free from the accumulated advantages or disadvantages of their ancestors.

This quote stood out to me as interesting. I know this isn’t what you meant, but as a society it would be really weird to collectively decide “don’t give the next generation fire, they need to start fresh and rediscover that for themselves. We shouldn’t give them the accumulated advantages of their ancestors, send them to the wilderness and let them start fresh!”.

I think I am not understanding the question this equation is supposed to be answer, as it seems wrong to me.

I think you are considering the case were we draw arrowheads on the lines? So each line is either an “input” or an “output”, and we randomly connect inputs only to outputs, never connecting two inputs together or two outputs? With those assumptions I think the probability of only one loop on a shape with N inputs and N outputs (for a total of 2N “puts”) is 1/N.

The equation I had ( (N-2)!! / (N-1)!!) is for N “points”, which are not pre-assigned into inputs and outputs.

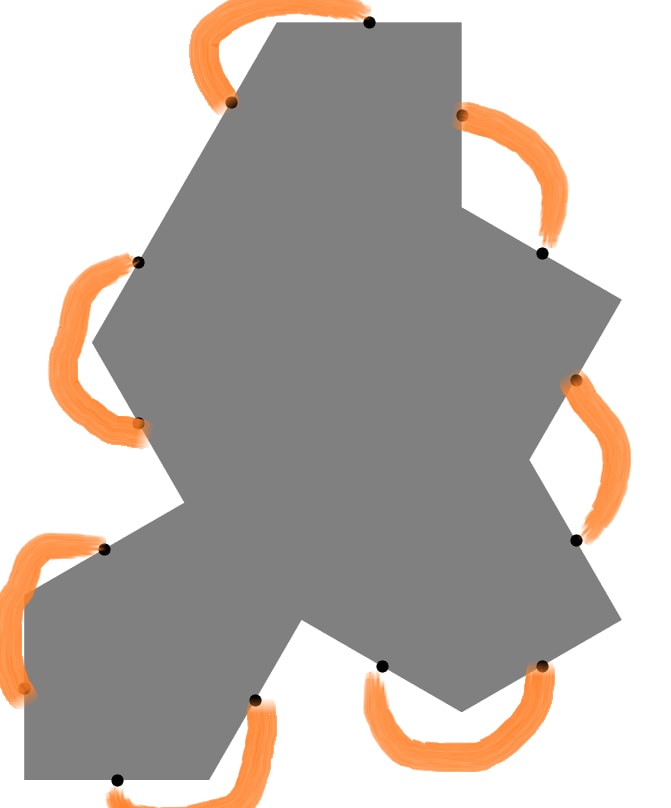

These diagrams explain my logic. On the top row is the “N puts” problem. First panel on the left, we pick a unmatched end (doesn’t matter which, by symmetry), the one we picked is the red circle, and we look at the options of what to tie it to, the purple circles. One purple circle is filled with yellow, if we pick that one then we will end up with more than one loop. The probability of picking it randomly is 1⁄7 (as their are 6 other options). In the next panel we assume we didn’t die. By symmetry again it doesn’t matter which of the others we connected to, so I just picked the next clockwise. We will follow the loop around. We are now looking to match the newly-red point to another purple. Now their are 5 purples, the yellow is again a “dead end”, ensuring more than one loop. We have a 1⁄5 chance of picking it at random. Continuing like this, we eventually find that the probability of having only one loop is just the probability of not picking badly at any step, (6/7)x(4/5)x(2/3) = (N-2)!! / (N-1)!!.

In the second row I do the same thing for the case where the lines have arrows, instead of 8 ports we have 4 input ports and 4 output ports, and inputs can only be linked to outputs. This changes things, because now each time we make a connection we only reduce the number of options by one at the next step. (Because our new input was never an option as an output). The one-loop chance here comes out as (3/4)x(2/3)x(1/2) = (N-1)! / N! = 1/N. Neither expression seems to match the equations you shared, so either I have gone wrong with my methods or you are answering a different question.

This is really wonderful, thank you so much for sharing. I have been playing with your code.

The probability that their is only one loop is also very interesting. I worked out something, which feels like it is probably already well known, but not to me until now, for the simplest case.

In the simplest case is one tile. The orange lines are the “edging rule”. Pick one black point and connect it to another at random. This has a 1⁄13 chance of immediately creating a closed loop, meaning more than one loop total. Assuming it doesn’t do that, the next connection we make has 1⁄11 chance of failure. The one after 1⁄9. Etc.

So the total probability of having only one loop is the product: (12/13) (10/11) (8/9) (6/7) (4/5) (2/3), which can be written as 12!! / 13!! (!! double factorial). For a single tile this comes out at 35% ish. (35% chance of only one loop).

If we had a single shape with N sides we would get a probability of (N-2)!! / (N-1)!! .

The probability for a collection of tiles is, as you say, much harder. Each edge point might not uniformly couple to all other edge points because of the multi-stepping in between. Also loops can form that never go to the edge. So the overall probability is most likely less than (N-2)!!/(N-1)!! for N edge dots.

Those jokes are very bad. But, in fairness I don’t think most human beings could do very well do given the same prompt/setup either. Jokes tend to work best in some kind of context, and getting from a “cold start” to something actually funny in a few sentences is hard.