HPMOR: The (Probably) Untold Lore

Eliezer and I love to talk about writing. We talk about our own current writing projects, how we’d improve the books we’re reading, and what we want to write next. Sometimes along the way I learn some amazing fact about HPMOR or Project Lawful or one of Eliezer’s other works. “Wow, you’re kidding,” I say, “do your fans know this? I think people would really be interested.”

“I can’t remember,” he usually says. “I don’t think I’ve ever explained that bit before, I’m not sure.”

I decided to interview him more formally, collect as many of those tidbits about HPMOR as I could, and share them with you. I hope you enjoy them.

It’s probably obvious, but there will be many, many spoilers for HPMOR in this article, and also very little of it will make sense if you haven’t read the book. So go read Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality before you read any further.

We talk about HPMOR’s characters, including how Eliezer tried to make every single character awesome, and why Hermione gets unicorn horn teeth. We talk about the plot, and learn some secrets about Harry’s sexuality. We talk about the setting, and Eliezer explains the Nested Nerfing Hypothesis of magic in the HPMOR universe. And finally, there’s some news about the epilogues—plural!

While I’m here, I’ll also mention that Eliezer has a non-fiction book coming out on September 16th, 2025 and I personally think it would be excellent if many thousands of people pre-ordered that book.

And now, on with the lore!

Characters

Masks

Gretta: Can you please explain the “dramatic masks” idea that we’ve talked about, and how it applies to HPMOR?

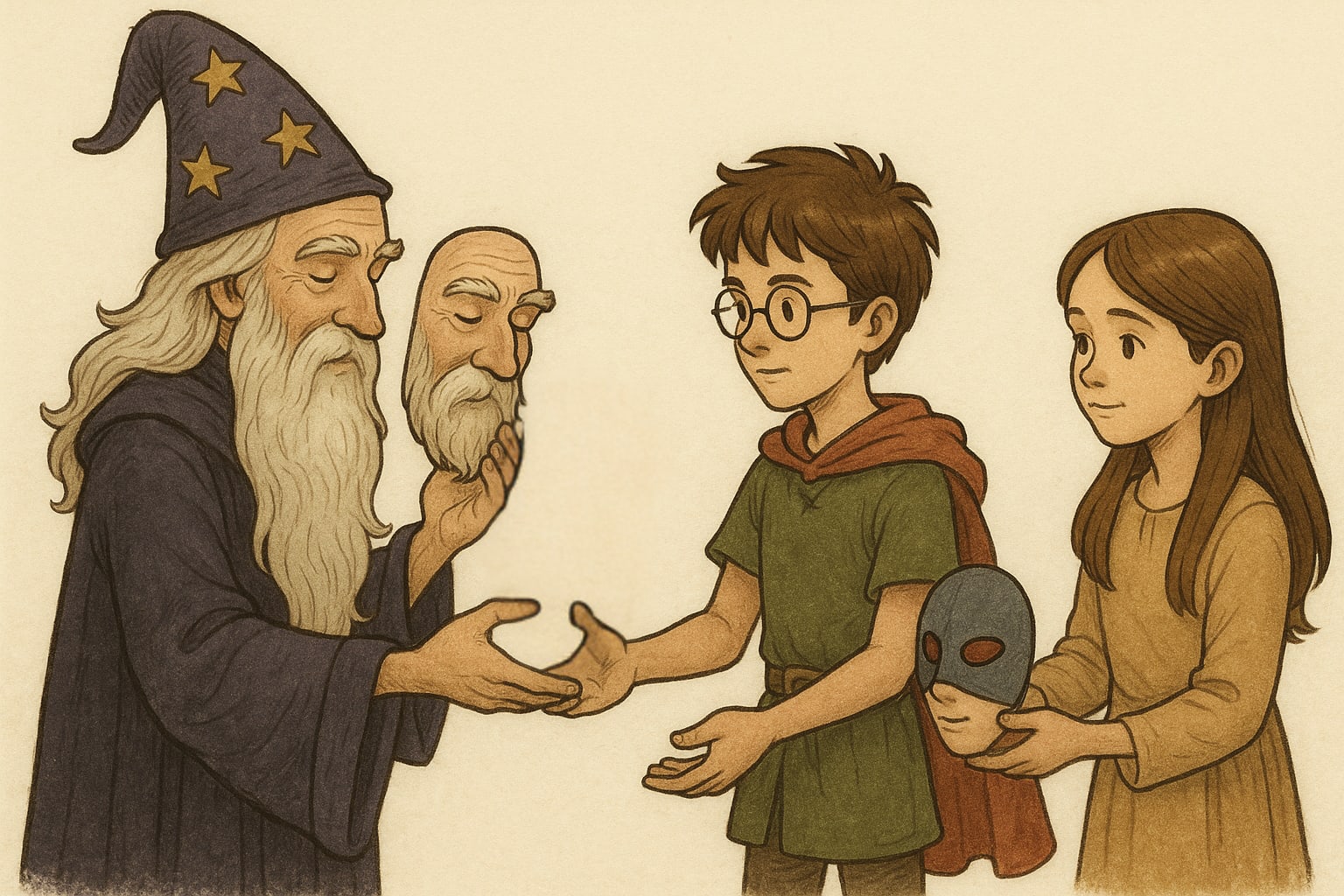

Eliezer: So there’s a science fiction and or fantasy author, Stephen R. Donaldson, who made an observation in the afterword to one of his books.[1] Donaldson says that the difference between drama and melodrama[2] is that in a drama, the characters change their masks over the course of the story, and in melodrama, they wear the same masks throughout the story.[3]

And in particular, Donaldson gave an example, which was more influential on me than the underlying statement, of how in one of his stories, it starts out with a victim, a victimizer, and a rescuer. And then by the end of the story, they have all exchanged masks.

Gretta: Okay. So three people, three masks. And they rotate. And I just want to clarify, when we’re talking about masks, we’re not talking about something that a character is pretending to do or be.

Eliezer: Yeah. This is the literary sense of mask. Like a role that a person wears inside the story, whether or not they’re conscious of it.

Gretta: So harkening back to like stage plays where people would literally wear a physical mask in order to indicate what character they’re playing.

Eliezer: Right. These are the masks of the stage play, not masks inside the play. They’re masks outside the play. Denoting which character you are.

And in a drama, according to Donaldson, they rotate. Now, Donaldson’s example is literarily perfect,[4] whereas HPMOR does not quite stand up the same way. There are only two masks for three people, and the masks themselves are different.

But by the end of the story the mysterious old wizard mask has moved from Dumbledore to Harry, and Harry’s brash young hero mask has moved to Hermione. (Hermione’s mask does not, so far as I noticed, move to Dumbledore.)

Gretta: What mask was Hermione wearing at the beginning of the story?

Eliezer: At the beginning of the story, she’s not quite asserting herself as having a mask. School know-it-all, maybe?

By the time she’s in the middle of the story, she’s got much more complicated things going on. She has multiple self concepts, plus she’s fighting against concepts imposed upon her by the school.

Gretta: What are her multiple self concepts?

Eliezer: To answer that, I need to back up a bit. This might sound initially like it’s not quite about characters. Orson Scott Card, I believe, observed that while a conflict between good and evil might hold the attention of some readers, a conflict between good and good can be much stronger than that.[5]

And why is this? Because for the same reason that a conflict between two strong forces is more literarily interesting than a conflict between a strong force and a weak force, if only one side has good arguments, that’s less of an interesting debate than if both sides have strong arguments.

And the extension of this to characters, and I don’t actually remember at this point, if this exact way of phrasing it is original to me or not, is that you might think of a three dimensional character as one who contains at least two two-dimensional characters.

Like, you just take a bunch of flat characters and put them all into the same person, and now, lo and behold, you have a three dimensional character.

The less interesting version of this is if the character has a good side and evil side, and/or a sympathetic side and an unsympathetic side. And the much stronger version of it is when they’ve got multiple sympathetic sides in conflict.

So coming back to Hermione — Hermione is, on the one hand, the hero, and on the other hand, a sensible young lady who has way too much common sense to go in for that sort of thing, both in the same person.

Gretta: Way too much common sense to go in for being a hero?

Eliezer: Yeah. At first, she’s too sensible to do all this dangerous stuff that Harry does — though later, she leans into the hero side and she goes off and does dangerous stuff too.

Gretta: I see. She knows better than that. She knows better than to take these kind of risks, or —

Eliezer: Yeah, or to get herself into this sort of trouble. She has this drive to assert her reality independently of Harry’s, despite how the lumpenproletariat of Hogwarts try to cast Hermione as Harry’s tagalong romantic interest, as a bit player in Harry’s story. Harry has a lot of sympathy for Hermione’s plight. He wouldn’t like it if someone tried to cast him as the sidekick, either, so he fights alongside her against the gossip network’s attempts to typecast her, but it doesn’t particularly work, Hogwarts continues to apply that false trope to Hermione.

And this is like a mask that she wears that is independent of her actual heroism. There’s some amount of performative heroism she’s doing to distinguish herself from Harry, but somewhat separately from whether she is an actual hero or not. Sometimes the actual heroism and the performative heroism overlap.

Gretta: What are some examples of performative heroism versus real heroism on Hermione’s part?

Eliezer: So the Society for the Promotion of Heroic Equality for Witches (SPHEW) is Hermione consciously wearing the hero mask. When she asks, “How can I be a hero?” she is consciously performing the hero role, consciously wearing the mask.[6]

But also, she hears the echoing cry of the phoenix, runs into an actual instance of bullying and stops it without very much thinking about it.[7] And that’s actual heroism.

Gretta: What happens to Dumbledore when he takes off the wise old wizard mask?

Eliezer: Inside the story, when Dumbledore loses his wise old wizard mask, he gets taken off the board immediately thereafter. He’s snapped out of time, sealed inside the mirror. Dumbledore knew that something like that was going to happen. He prepared for it in advance.

But it’s also interesting to consider what we learn about Dumbledore, who he really was, underneath that wise old wizard mask, which was after all just a role he was playing, and a role that he lost at the end.

When we find out that Dumbledore has been reading prophecies, this changes his apparent role in the story even in retrospect. It’s a moment of not just changing ongoing roles but also of revealing that he had a different story role than we thought on first readthrough. Now his actions make sense in a different way. We know what he was thinking and not just what he was doing.

We also find out that he was mistaken about a few of the prophecies. He thought some of them were about himself, but they were actually about Professor Quirrell, who was also Harry’s mentor.

On the object level, though, what happens is that he’s out of the game.

Gretta: Yeah, it’s rough when there’s no mask for you anymore. It’s like playing musical chairs and, whoops, no chair for you.

Eliezer: Yeah. Dumbledore might get one back at some point. That would be a matter for the future of the story.

Imperfect Characters

Gretta: In my writing books, it says to give your characters and especially your protagonist flaws, but you write about having respect for your characters, including for your villains.

So what in your mind constitutes a respectable flaw?

Eliezer: There are many kinds of respectable flaws. But a very strong, classic pathway is to take a mistake that you made in the past and that you’re still sympathetic to yourself for having made.

You’re like, “Yeah, that was a mistake, but I had reasons for that mistake that was not just me being stupid, all of my books gave me the wrong advice, I was trying to do the right thing there. I had no way of knowing this.”

And I’m not saying to go around being sympathetic for yourself to yourself for all your mistakes. But maybe there are some that, despite your strong Irorian self-improving heart, you can still manage to find some sympathy for yourself for making. And especially, maybe you remember how at the time it didn’t seem like a flaw to you. You were not going around being like, “And today I shall be a flawed character.” You were trying to do the right thing, and not perform doing that in any flawed way. But then you made the mistake anyway.

Gretta: So does this mean that you can only write characters who are flawed in the same ways that you personally have ever been flawed? Or is that just one wellspring for it?

Eliezer: That’s one wellspring. And the thing I would say is just keep yourself to the same standards when you’re inventing whole new flaws.

The thing that you may remember about your own flaws that you’re still sympathetic about, is that you did not arrive at these flaws by wearing the flawed mask in the theater and setting out to be flawed that way, so that you could have sympathetic flaws to your reader. No. You made a mistake. You screwed up even though you were trying.

Gretta: So now let’s bring it back to HPMOR. Could you please run through some characters and tell me what their flaws are, how you conceived of them, and how you made sure that they were respectable flaws?

Eliezer: So McGonagall. Some people thought that I treated McGonagall unfairly. If so, I wasn’t trying to.

I was trying to write McGonagall as not yet up to Dumbledore’s caliber for a wise old mentor. She has the potential to become headmistress of Hogwarts and raise future generations to be people with strong integrity. But initially, she is mainly trying to keep these kids under control. That to me does not seem like an unsympathetic motivation, but it is not as large as it could be, and it leads her into some errors. In time she does come to regard it as a flaw within herself, and thereby change.

Then take Harry. Harry’s, like, gung-ho. I sometimes tell people that Harry is me at age eighteen, but with my Wisdom and Constitution scores reversed and all the brakes taken off. So one of Harry’s flaws is that he doesn’t have his brakes on.

I charged ahead more when I was young than I do now. Maybe never quite as much as Harry, but more. And when I look back at myself, I don’t see someone who made entirely defensible mistakes, knowing everything meta that I now know. I see somebody who charged ahead and made mistakes, like Harry, but also somebody who knew a bit more than usual, got some things right that others got wrong, and was trying to do the right thing. This is what I draw on to respect a character like Harry. I know what it is like to be a coherent person who is trying to reflect on himself and still misses some things.

Gretta: So by charging ahead, you mean he acts when he would benefit by instead thinking longer first?

Eliezer: Yeah. Probably not the way I would’ve phrased it, but also a thing that is occasionally true of him.

Only it’s not necessarily thinking longer. If you think the same thoughts for longer, you’re not necessarily gonna arrive at a different destination.

Gretta: Does he consider too few possibilities?

Eliezer: We all consider too few possibilities. We literally cannot fit enough possibilities in our head for the truth to reliably be inside our considered hypothesis space. Harry has just not had enough bad stuff happen to him at the start of the story.

Gretta: His priors are too optimistic.

Eliezer: Yeah.

Gretta: His parents are nice.

Eliezer: He doesn’t realize that, of course. He doesn’t know that he is in a story with a nice version of his parents. Yeah. But they are nice.

Gretta: Yeah, they are.

What about Draco? What are Draco’s flaws?

Eliezer: You might more strongly ask, what are Draco’s strengths? Or something like, how do you even set up Draco such that, in the course of being a Death Eater, he is not performing the flaws, being the character that has been handed the flaw card — but instead merely is flawed.

And my answer there is, he’s a good kid who wants to do what his father tells him to do, and live up to the morals that his father has inculcated in him and carry on the honor of House Malfoy and all that. And he doesn’t know that he’s supposed to be the villain.

And this is his strength. Nobody at any point has told Draco that he is the villain of the story and in the end that means that he’s not.

Gretta: Yeah. Cool. Who else would be a good one to touch on here?

Eliezer: Pansy Parkinson just wears her flaw mask and doesn’t know that she’s supposed to be wearing anything else.

She’s a minor character. She has like only a few lines or, like one scene. And is just straight up wrong as far as I can remember.

And this is not true of many people in HPMOR, but —

Gretta: I can’t remember what her deal was. Can you remind me?

Eliezer: I think she has a couple of unsympathetic lines here and there, and is mainly on screen at the point where Tracy Davidson deceives her into believing that she has eaten her soul.

Gretta: Got it. So for a very minor character, they can just be one-dimensionally bad, and this is fine.

Let’s go back to the general idea of character flaws. So far you mentioned one good wellspring for respectable flaws: mistakes you, the author, have made in the past. But here’s another framework, or generator for flaws.

I watched the Sanderson lectures and he talks about a few different kinds of flaws you can give your characters, and I found this helpful to think about.

Sanderson says you can give your characters a moral flaw, like being greedy. But you can also give them restrictions or limitations. A restriction is something like Superman’s moral code, where there are actions that he will not take because he has this moral code that’s more important to him. And a limitation might be something like, I don’t know, you’re missing a limb. So there’s actions that other people can take that you can’t take ’cause you don’t have the arm.

Eliezer: I don’t think of those as character flaws, per se.

Gretta: Yeah, it’s not so much that they’re categories of flaws according to Sanderson. It’s more like when you’re trying to make a character and you’d like that character, not just to be the nicest, most awesome, most powerful. It’s boring to have a character who’s just OP[8] and everything is great for them. These are some different ways you can hobble your protagonist.

Eliezer: Weaknesses, let us call them weaknesses.

Gretta: Perfect. Yes. These are different ways you can hobble or shape your protagonist so that they have a harder time accomplishing their goals, but also they are more textured, more themselves.

Do you ever think about those other kinds of restrictions and limitations as being a useful way to shape a character?

Eliezer: Sure. Harry’s Time-Turner is limited to six hours.

But overall, character weaknesses are among the relatively trickier things to navigate. It’s all too easy for weaknesses to just visibly be grafted onto a mask.

If your character is blind, there’s this whole delicate line to walk: “How do I reflect the actual magnitude of how hard this hits them without having this be all the character’s about?” Or maybe it is all the character’s about, that’s a different set of thin lines to walk.

And especially to all the beginning writers out there, before you say, “how shall I take a weakness and slap it onto this character?” First ask if there are just organic vulnerabilities in this character that you don’t need to slap on top. And even before that, ask, can you just strengthen the opposition, the problems, the environment, the antagonist.

Gretta: Okay. You made two points there. Say more about organic vulnerabilities?

Eliezer: Who needs a special vulnerability to magic when you’ve already established that this character has the kind of moral code that can get them into trouble with a more powerful opponent?

Gretta: So instead of throwing more weaknesses at them, check and see if you fully plumbed the depths of the weaknesses they’ve already got, is that close?

Eliezer: Yeah. And if you feel like a weakness is just inherently part of a character and not in a looking down on them sort of way, but, like, this delicate sculpture all fits together, then by all means have that weakness there.

But if somebody says, “Ah, your character’s too strong. You need to slap some extra weaknesses on there.” Then I’m like, “Oh, this is not about to end well, for this burgeoning young author.”

Gretta: I think I understood the other point, which is: don’t make your character weaker, make everybody else stronger, and then you have more epic battles.

Eliezer: Yeah. There’s a version of HPMOR where you can imagine some author who had received less good advice thinking, “I’ve got my very rational character. They’re very intelligent, that’s a strength. I gotta slap a weakness in there. How about if he’s totally clueless about emotions? How about if he doesn’t understand other people?”

And where HPMOR goes instead is,”Alright. Draco’s got some good training. Hermione is gonna beat the pants off of Harry in all his classes except for broomstick riding. The Defence Professor is gonna be the older, wiser, and more evil version of himself. And Dumbledore is gonna have access to all the prophecies.”

I didn’t slap a bunch of weaknesses on Harry. I just put him in an environment where the character could hold together without needing a bunch of weaknesses slapped on top, like rotten cherries on a cake.

Gretta: Gross.

Make All the Characters Awesome

Eliezer: So to generalize that, let’s talk about the principle of “Make All the Characters Awesome.” This was an explicit process as I was envisioning the story, where I thought, for each character, how can I make this character awesome?

Take Crabbe and Goyle, for instance. I had an explicit process of flipping through various ideas, like, “Okay. Can I have them be like the Secret Masterminds who are running Draco from behind the scenes? No, because then Draco’s not awesome.”

“Can they be Secret Masterminds running all of Slytherin from behind the scenes? No, because that doesn’t really fit.”

“Could they be Those Two Bad Guys, as TVTropes named the trope? I think this trope is used in Pulp Fiction and maybe in Neverwhere, if I’m remembering the correct Neil Gaiman novel. Anyway, so I’m like, “How about if there’s Those Two Bad Guys?” And I thought, “Eh, it doesn’t quite fit. It’s been done before. It’s a little arbitrary. Why is this trope showing up here?”

And then I thought, “No, no, see, Crabbe and Goyle saw plays with Those Two Bad Guys as kids, and that’s who they think they’re supposed to be!” And then I was like, “Alright, this is adequately awesome.” And then I could stop trying to figure out how to make those two characters awesome and move on to the next character.

Gretta: Let’s do one more.

Eliezer: Sure. How about Luna Lovegood?

A fundamental fact about Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality is, it’s not quite set in the world of canon, it’s set in the world of fan fiction. And almost every fan fiction out there makes Luna Lovegood awesome. So this wasn’t just me making every character awesome, this was a required element.

But HPMOR is set in Harry’s first year at Hogwarts, and Luna is younger than Harry, so she’s not even enrolled at Hogwarts yet.

So I put a lot of effort into figuring out any way that she could be onscreen at all and awesome.

I landed on having her write all the Quibbler headlines. Had we ever made it to the epilogue, she would’ve been onscreen and even more awesome.[9]

Hermione as Mary Sue

Eliezer: While we’re talking about characters, I want to tell you a little-known aspect of Hermione Granger. I wrote her explicitly to be a deconstruction of the Mary Sue. Some people accused J. K. Rowling of having made Hermione Granger a Mary Sue. And other people were like, how dare you? Nobody would look twice at this character if she was male.

Gretta: Please explain Mary Sue, because some people aren’t going to know what that is.

Eliezer: Ah, golly. Now I feel old.

So long ago, I believe there was a character named Mary Sue in one of the first fan fictions. It might have been a Star Trek fanfiction, I’m not sure.[10] In this story, a character named Mary Sue came along, and she was stronger and smarter and prettier than the original characters. She just took over all the story and solved all the problems. In some versions of this legend she bore a certain resemblance to the author, except of course for being prettier.

And so Mary Sue came to denote this perfect character who steps in and solves all the problems and is always right. She’s stronger and prettier and takes over the story. Sometimes she turns out to be secretly related to the original characters despite having not been in the original story.

Gretta: And so people accused Rowling of making Hermione a Mary Sue.

Eliezer: Yeah, on account of Hermione being good in class and sometimes stronger than Harry at things.

Gretta: And then other people said, “Come on, if she was a boy, it would be fine for Harry to have a rival. You’re only mad because she’s a girl.”

Eliezer: Sort of? I don’t think they were really rivals in the original Harry Potter because canon Harry Potter wasn’t that good at academics.

Anyway, I set out to make Hermione check every single box in the Mary Sue trope. But you probably don’t even notice that I did it, because the thing that actually makes a character pose the literary problems of a Mary Sue has nothing to do with whether you die three days before Easter and later come back from the dead.

(I thought about having her die on Good Friday but I thought that was just a little too unsubtle. As it turned out, I was just vastly overestimating clarity and I wish I’d straight up had her die on Good Friday.)

So yeah, I had her beat Harry at all of their classes except broomstick riding. I had her die and come back from the dead. I gave her pearly white teeth made of unicorn horn. I gave her the reputation for being the one who destroyed Voldemort, just because he dared to try to touch her.

And then there was one part that was more subtle. I think very few readers and only the most obsessive ones on Reddit even guessed at this one, but Hermione is secretly the grand-niece of Professor McGonagall. McGonagall has a dead sister who died in a war, while Hermione’s mother thinks that probably her mother died in that war.

Gretta: Okay. So a very subtle hint.

Eliezer: Yeah, very subtle hint. And also later on, you see McGonagall holding Hermione, and the text remarks as if she were holding her daughter or maybe granddaughter.[11]

Gretta: So you’re really trying to check all the boxes on the Mary Sue trope.

Eliezer: Yeah. There is no other reason for Hermione and Professor McGonagall to be related, except that I wanted Hermione to have the supposedly Mary Sue property of being secretly the relative of one of the existing characters.

Gretta: But you never hear anyone complain that Hermione just took over the story of HPMOR.

Eliezer: That’s because she didn’t! So there you go, that’s it, that’s all that a Mary Sue isn’t. Hermione didn’t get to steamroll over everything. The story didn’t reshape itself entirely around her. The other characters weren’t there just to be part of her magnificence.

And that’s all a Mary Sue really is. Who cares about a character coming back from the dead or having pearly white teeth made of unicorn horn?

Who’s the Main Character?

Gretta: Most people would probably just say that Harry is the main character of HPMOR, but you’ve told me it’s a lot more complicated than that. So how many protagonists does HPMOR have according to you, and according to the characters themselves?

Eliezer: When you’ve got something as complicated and occasionally meta as HPMOR, the concept of a protagonist does tend to blur a little bit.

There are at least three ways to look at it. One, which characters see themselves as the “main character” from their own viewpoint? Two, who is the viewpoint character? And three, who makes choices that move the story?

Almost everyone is the main character from their own perspective, at least in HPMOR. I am not sure what the ratio is in the real world.

Gretta: Is there anyone in HPMOR who is not?

Eliezer: So for example, Professor McGonagall doesn’t see the world as it relates to herself. She sees the world as it relates to Hogwarts.

But if you think about that second category, viewpoint characters, then Harry, Hermione, and Draco are the most obvious ones. Then we get into secondary viewpoint characters like Snape or McGonagall.

Gretta: Does Neville think he’s the main character?

Eliezer: No, but the story sure treats him as one whenever we take on his viewpoint.

Neville sees the parts of the world that relate to Neville. Neville thinks about how it’s his fault that Hermione got killed, or that Bellatrix Black has escaped. From Neville’s perspective, obviously these events are part of Neville’s story.

Gretta: Yeah. Okay. That makes sense.

Let’s talk about the third category. There’s an awful lot of students at Hogwarts. Most of them are not actually moving and shaking, making choices that drive the story.

Eliezer: Yeah. But moving and shaking is a very distinct quality from being the main character or a viewpoint character. Dumbledore is making a fair number of choices that move the story. But the viewpoint does not tend to linger on him. And he knows perfectly well that Harry is the main character.

Gretta: So what does it mean for Dumbledore to think that Harry is the main character?

Eliezer: Dumbledore knows the plot more or less. Not in a literal sense, but Dumbledore knows the larger plot. He knows that large events are moving and Harry’s going to drive them. He’s not quite sure of the extent to which the same holds of Hermione.

And Dumbledore is pretending to be this person who believes in tropes, as opposed to a person who has read the prophecies. So he is constantly talking as if Harry is the main character as a trope, not expecting to be believed, because the people he is talking to know that they are not characters in a story. Meanwhile Dumbledore is taking great quiet amusement that Harry is the for-real main character in prophecy and not even Harry knows it.[12]

| Character | Sees self as protagonist | Viewpoint character | Makes decisions that move the story | Main character according to prophecy |

| Harry | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| Quirrell | ✅ | ((✅)) | ✅ | |

| Hermione | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | |

| Draco | ✅ | ✅ | ||

| Dumbledore | ((✅)) | ✅ | ||

| McGonagall | (✅) | |||

| Snape | (✅) | |||

| Neville | (✅) | |||

| Pansy (e.g.) | ✅ | ((✅)) |

Eliezer: Also worth noting and in a very similar vein, there’s a lot of Only Sane People in Hogwarts. People who are all, according to their own story viewpoint, the Only Sane Person and with considerable justification, include Harry, Quirrell, Dumbledore, Hermione, McGonagall, Susan Bones, and Amelia Bones. Draco Malfoy sure sees himself that way too. Even Daphne Greengrass, at one or two points, wonders when she became the only sane person in Hogwarts. It’s not quite the same thing as seeing yourself as the main character or protagonist, but it’s related—the sense that you’re the only one who’s not just bound up in the mad movements of the world, as the mad other people enact their play. Giving that feature to everyone’s own viewpoint is a similar sort of literary motion to making them all their own viewpoint’s protagonist.

Contrast canon Harry Potter’s Voldemort, who does treat Harry Potter as the main character. Voldemort does not seem to have much to do with his time on Earth besides being a villain over Harry Potter. His plans mainly center on Harry Potter or threatening things valuable to Harry Potter. You can tell that Voldemort is not at the center of his own story.

Plot

Characters interfering with plot

Gretta: You say that any level one intelligent character will try to toss your plot out the window. Do you remember any instances of this happening to you while you were writing HPMOR?

Eliezer: Oh, yeah. Let me think back here for a second.

So in terms of characters, like just straight up announcing that they will not cooperate with the story you have written, there is a good example in the original version of the Azkaban breakout. I had planned for Harry to transfigure the rocket for himself without any other assistance and ride that rocket out.

And I realized that this would not work and Harry was inevitably going to die. And that even if I tried to get away with ruling by authorial fiat that it worked, my readers wouldn’t believe it, and also Harry himself would just not have done that.

I think there were several points in the Azkaban arc where Harry was like, “Nope, I’m not doing that. This is suicidal. I need to invent something else.” And I was like, “Okay.”

Gretta: Alright, so you were making life too easy on yourself. You were grabbing for an easy solution and then your character was like, “I don’t buy it.”

Eliezer: The classic example, from my perspective, is when you’re trying to steer your character into trouble and your character says, “screw that.”

Gretta: What you just said was the opposite. You weren’t trying to steer Harry into trouble. You were trying to get him to escape the tower and then he wouldn’t.

Eliezer: Yes, but I was having him go down the corridor of the prison without having invented, like, a Patronus substitute or something.

This might not be the best example, but I do remember the Azkaban arc as my characters being like, “Why would I do that?” And then you have to manipulate external conditions to cause them to actually do the things you want them to do.

Oh, here’s a better example. How could the Defence Professor get Hermione into a position of conflict with Draco? In the first drafts and outlines of the story, I didn’t realize, there was no indication that he would have to go to such lengths. It turned out to be hard even to get Hermione to the point where she could be false-memory-charmed about having tried to kill Draco. It took multiple setup chapters.

The Defence Professor inside the story had to go pretty hard on setting that up, ’cause Hermione didn’t particularly want to cooperate with the Defence Professor’s first ideas and my own first draft.

Gretta: What were Hermione’s objections?

Eliezer: “That’s evil. I ain’t doing it even if somebody sets me up to think I have a reason.”

And similarly The Society for the Promotion of Heroic Equality for Witches. I think there’s a bunch of things inside my first story ideas where these sensible young ladies were like, “we are not going to do that.” And I was like, “… yeah, fair.” I don’t remember the specifics, but I was like, “Yeah, okay. I will have to give you a bigger push. So… what if you got this mysterious note?”[13] Or, “what if one of your people turned out to have more firepower than you expected them to have?”[14]

I’m trying to remember whether I, at any point, had Chamber of Secrets Shenanigans Plans, which Harry derailed by just sensibly telling Professor McGonagall about it. But I just don’t remember at this point if that was ever true.

Gretta: Yeah, a major flaw in many books about young wizards or just children in general is, “Oh my god, why didn’t you just ask a grownup for help?”

Eliezer: Yep.

Gretta: And how did you deal with that in this book?

Eliezer: By giving all of the people who would otherwise have derailed the plots that way, adequate reason to suspect all of the grownups they could have potentially talked to. For example, Harry sees Dumbledore setting fire to a chicken. No way Harry’s going to Dumbledore for sane help after that.

By the time Harry’s getting himself into real trouble, I had to make sure McGonagall had acted as an obstacle to him. McGonagall has to be maneuvered into telling Harry that she doesn’t want to hear anything wrong about the Defence Professor. Yeah, it’s played for laughs at the time. But really this is me asking, “How the hell am I gonna prevent these people from being sensible?”

And the answer was: “All right. There is a curse on the Defence Professor position. There has always been a curse on the Defence Professor position. The school has adapted to it. Harry has gotten into just the right kind of shenanigan to cause McGonagall to panic about this, and give Harry the instructions he needs to hear to prevent him from just taking certain matters to McGonagall.”

Setting up Plot Twists

Gretta: Yeah. Okay. So on that note, you wrote this one chapter at a time. You knew in general where you were going the whole time, and you had some of the major building blocks in mind.

But this book is a very layered book with forward references and, like, forward references to forward references. There’s so much going on here, how did you do it?

Eliezer: In part by writing a bunch of later scenes out in some detail. They did have to be re-written when I got there.

For example, the troll killing Hermione was written out, not just in outline form, but line by line, way in advance.

Gretta: Okay. That is a more comforting answer than I actually expected to get from you. I expected you to say, “I held it all in my head because I am just that good.”

Eliezer: I held surprising amounts of it in my head because I am, or at least was at that age, just that good. But I did not hold it all in my head. There were outlines, there were places where things were going to go. And it didn’t fit together perfectly. I had to try so hard to close the parentheses. I put so much effort into, “Oh no, I opened these parentheses. Now I must close these parentheses.” I would internally scream and struggle invisibly, or even visibly, for several chapters to do that.

Gretta: Okay. Can you think of any parentheses that particularly irked you, that were very hard to close?

Eliezer: The example that leaps out in my mind is — trying to arrive at a point where would make sense to have the aurors tromp in and arrest Hermione Granger for the murder of Draco Malfoy, without that seeming to come completely out of the blue.

The entire Society for the Promotion of Heroic Equality for Witches was not in the original outline. SPHEW is just me trying to set it up so that, by the time these people come in and arrest Hermione, it actually makes sense.

And her arrest had to be a consequence of her own actions, in at least some sense, for certain themes of the story to hold together. In real life, stuff happens to trash you all the time, but inside the story, this had to be, somehow and however loosely, Hermione’s knowing choice.

Gretta: So you had to do a lot of back propagation. There were many beats you were trying to hit later in the story and it just had backwards implications, layers and layers deep.

Eliezer: And that works in both directions. So many chapters, I’m trying to get this story to where it has to be in a future place. And then in so many future places, I’m doing so much work to close the parentheses that opened in an earlier chapter. That’s how I ended up writing a layered story even though I was publishing it linearly, as a serial.

Time-Turner Plots

Gretta: While we’re on the subject of plot intricacy, tell me about how you reasoned through the Time-Turner plots.

Eliezer: Someone once asked me, “What sort of note-taking or outline do you use for the Time-Turner sections? It seems hard to keep it all self-consistent.”

And this time the answer is, “I just write it.” I wrote those sections in short, connected writing sessions and published a bunch of closely related serial events that I could just hold in my head. I couldn’t hold the whole story’s plot from start to finish, but the Time-Turner sections, I could.

That person might have felt impressed, I’m not sure, but it’s not as impressive as it looks. They were trying to decode the plot I had written, and they were probably juggling multiple possibilities in their head until the evidence came in, and I only had to hold one possibility in my mind and sweep it forward.

This would actually catch me out sometimes! A lot of times my readers would see completely valid alternative interpretations that I’d never intended, and that I had arguably inadvertently foreshadowed. But because I was only holding my intended interpretation in mind, I didn’t anticipate what they would see.

So for example, some people made a very clear case that I clearly foreshadowed that Professor Quirrell was a time traveling version of Harry. Because in chapters quite close to where this sense of doom was introduced, I happen to have Harry thinking, in the course of discovering Time-Turners, that time-reversed matter looks like anti-matter and explodes when brought into contact with matter. This is obviously me telling all the attentive readers that the reason for this sense of doom is that Professor Quirrell is a time traveling version of Harry. It makes sense! It’s also false, it’s not what I meant. I wouldn’t have left that red herring if I’d thought about it. But because I knew what I meant, I didn’t realize it was a red herring.

Slashfic?

Gretta: I have two sex-related questions for you about this mostly PG-13 rated book.

My first question is about Quirrell’s humiliation of Harry at the end of chapter 19. Quirrell forces Harry to submit while several bigger students incapacitate him. He requires Harry to beg for mercy before calling the bullies off. And then when it’s over, Quirrell praises Harry and sends him to a cozy room with a light novel and some chocolate.

When I read that, I thought, “Oh, I’ve just read some slashfic,[15] how daring,” but you’ve told me that this was not at all what you intended. Say more.

Eliezer: You are not the first person to bring this up. My partner at the time I wrote HPMOR also claimed to me that Harry and Professor Quirrell had the BDSM nature. And I was like, “No, but BDSM sometimes has the Harry / Quirrell nature.”

Let’s say you subject somebody to a highly stressful experience (which you might want to do for any number of reasons). And furthermore, let’s say you are clever, as Voldemort is, and you don’t want to break them, and you want them not to resent you afterwards —

Putting them in a quiet room with some chocolate is the obvious thing to do. You don’t actually need to be in a kinky or romantic relationship with somebody to give them aftercare. You can also be Voldemort and have plots.

Gretta: Were you surprised when some people read chapters 19 and 20 and came away thinking they just read some BDSM?

Eliezer: I think that relatively few people did report that reaction to me. A much more commonly reported reaction was of immense mood whiplash. And in this, they were simply correct.

There was too much mood whiplash, too fast. And a bunch of people were like, “What the hell is going on at that school?”

And I was like, “Have you read canon? This scene would have fit right in with the stuff that teachers are doing in canon Harry Potter.”

Gretta: Yeah, Dolores Umbridge does some absolutely horrible things to the children in canon.

Eliezer: Or Snape. And I felt like this fit right into canon.

But in HPMOR, this is the first sign of things having escalated to that level. There was some amount of that from Snape earlier, but Snape’s cruelty was undercut because it was clear that Snape had cooperative reasons for pulling that particular shenanigan.[16]

Quirrell’s cruelty in chapter 19 is inadequately foreshadowed. To write it better, something like that, but less so, needed to happen to Harry earlier.

Gretta: So you have a regret as an author?

Eliezer: I have a regret as an author about the extent to which many people correctly experienced this as coming, if not out of nowhere, then out of, like, inadequately somewhere.

Gretta: Okay. So it was just too harsh, too sudden.

Eliezer: Yeah. Whiplash in that it doesn’t match with the prior tone.

Gretta: Yeah. The overpowering and the humiliation was pretty massive at that point. But the part that really surprised me was Quirrell following up with aftercare. When Snape and Umbridge are horrible to the kids in canon, there’s no chocolate and light novel afterwards.

Eliezer: Man. So the big thing to remember about all of HPMOR is that, just as in the original books, the Defence Professor was Voldemort, and I thought it would be way way more obvious than it was to the readers.

Gretta: You thought everybody was gonna know that, but in fact people had all kinds of theories.

Eliezer: Yeah. And so the intended thing you’re supposed to be feeling here is something like, “Oh, noes, Voldemort is doing all these terrible things to the protagonist, what could he possibly be planning? Oh, noes, chocolate, he is being cruel and then arranging for the protagonist to still have this very high opinion of him. What is he planning? What is he plotting? Is the Philosopher’s Stone still here? What will become of it?” And, yeah, that’s what I thought people were supposed to be feeling in that particular section. And it is utterly legitimate of them that they did not.

The number one thing HPMOR taught me as an author is that you are being so much less clear than you think you are being. You are telegraphing so much less than you think. All of the obvious reads are so much less obvious than you think. And if you try to have subtle hints and foreshadowing laced through the story, clues that will only make sense in retrospect, that’s way too subtle.

Instead, you should just write very plainly reflecting the secrets of the story. Don’t try to hide them, but don’t explicitly spell them out either. That will be just right.

Why doesn’t Harry like-like Hermione?

Gretta: Here’s another question in the sex and romance direction.

In my reading of HPMOR, it looked like Hermione is interested in Harry, at least for a while, in a romantic way, but Harry doesn’t really reciprocate. He’s very fond of Hermione, he loves her as a friend, but he’s not really interested in being with her in a dating kind of way.

When I read this, I figured that Hermione had gone through puberty and Harry hadn’t. Maybe next year Harry will have different hormones and he’ll change his mind. But when I talked to you about it, you told me something different.

And I think you’ve never gone on the record about this bit anywhere else.

Eliezer: I don’t remember going on the record about this!

I should also note that what I am about to say is merely Opinion of God here, not Word of God.[17] It doesn’t become real until the story proves it. Maybe someday I will complete the epilogue and then the story will prove it. Although also there is one part of HPMOR that sure was written straight from this model.

My model is that at some point in his past, Voldemort had sacrificed the sexuality and romance aspect of himself in a terrible, dark ritual. What did he get in exchange? No longer aging, probably, that would be the obvious thing. But it was a good sacrifice for him to make because he just wasn’t getting very much out of the sex and romance part of his life.

And thus Harry is starting from a very blank slate in the sex and romance department, until puberty kicks in and his own brain areas grow up in that particular way. He has no adult knowledge of sexuality. He has no adult knowledge of romance from his dark side.

Gretta: So, then, my reading was not incorrect, it was just incomplete. It is true that Hermione is old enough to get crushes and Harry is not, and they just have bad timing. Right?

Eliezer: Right. But there’s more! This model also explains why, when Harry faces the Dementor and is lost in his dark side, and Hermione brings him out of it with a kiss,[18] Harry’s dark side has nothing to say about that kiss, it’s at a loss. Meanwhile, the main part of Harry has a thought process activated.

Harry’s dark side, as I model it, is not actually supernatural. It is a bunch of stuff that got written into his brain and then erased by childhood amnesia. So he’s got a bunch of habits that chain into each other.

(I parenthetically mention that one of my deflationary hypotheses for why people say they get new thoughts when they’re on drugs, is just that some drugs, like psychedelics, disrupt patterned chains of thought. Normally whenever we think thought X, we then go on to think thoughts Y and Z in a familiar pattern. But taking psychedelics is one way to disrupt those patterns and think new thoughts instead. The deflationary hypothesis is that any kind of mental disruption would do it, that the results are not specific to the drug; you’d need to demonstrate some tighter correlation to get past the deflationary hypothesis for that drug.)

And that’s what I model as happening to Harry when Hermione kisses him. The main part of Harry recognizes this weird stuff going on with Hermione. It originated when they visited her parents’ house and so on.[19]

And his dark side has none of this. Hermione’s kiss is a thought, a stimulus, a thing to react to, and his dark side doesn’t latch onto it at all, but the main part of Harry latches on, and that’s why her kiss brings him out of dementation.

Dumbledore’s reaction is, “Wow, not even I would’ve expected that to actually work.” But even Dumbledore did not know that Harry’s dark side had sexuality and romance obliterated.

Gretta: Nifty. Thanks.

Setting

The Truth of Magic in HPMOR

Gretta: What is the truth of magic inside HPMOR? Where does magic come from, how does it work, what governs who is magical and who is not, and so on?

Eliezer: Well first off I need to start by saying that the only ultimate truth of magic inside HPMOR is that J. K. Rowling invented a magic system for a children’s book. (Remembering always that children’s books are harder to write than adult books.) Her magic system has the structure of a certain kind of thing that flows from a human mind. It has the structure of the sort of thing that humans make up.

This is the only truth that can compress the magic system, that can create a system of explanation that is smaller than the magic system itself.

Okay. Nonetheless, we can try to rationalize it.

Gretta: And by rationalize here, do you mean make more rationalist?

Eliezer: No. Here I am using the standard English definition, of making up reasons for things.[20] Calling that “rationalization” is like if lying were called “truthization”, but it’s the linguistic standard.

Anyway, let’s go back to making reasons up about magic in canon Harry Potter and by extension HPMOR.

Suppose you found yourself somewhere in the multiverse. Somewhere that wasn’t just a place where J. K. Rowling made up this magical system, and nobody else made it up either, but it existed anyway. What might have happened? What could possibly give rise to a universe like this?

This is still in some fundamental ways an unanswerable question. ’cause once again, the real answer is, why are you looking here? You’re looking here because it resembles something that J. K. Rowling made up.

Even so, we can try to rationalize it. Even though the only true way to make a compressible magic system is to start from some simple set of postulates and then unfold them. You can’t add on the simple postulates afterwards. It’s like trying to compress a file that was generated by a random device —

Gretta: You can’t losslessly compress a truly random file.

Eliezer: Yeah. Only structure that’s already there can be unfolded and end up not random.

That said, rationalizing it, carrying out a fundamentally invalid operation —

The story that the people inside the universe would’ve eventually come up with — Harry, Hermione, Draco et al. — Would’ve been the Nested Nerfing[21] Hypothesis.

In my private worldbuilding there is an old magical philosopher, who I never had time to reference inside the story, who asked, “Look at all the apparently non-magical stars. Look at how the Muggle world is apparently larger than the magical world. Is the true nature of the universe magical or mundane at bottom? It must be magical, I reason, because if you have a magical universe, it’s easy to cast a spell that gives rise to mundanity. But from inside a mundane universe, how can you ever get to magic?”

So the universe was magical from its very start. But to explain this further, I first need to make a digression into magical genetics.

Magical Genetics

Eliezer: Magic, in canon, seems to be mostly hereditary. Wizards mostly give birth to wizards, Muggles mostly give birth to Muggles. Then where do Muggleborns[22] come from? And for that matter, where did wizards come from in the first place?

The first idea is that perhaps you can get there via mutation. So magic would spontaneously arise, and it’s a beneficial mutation so it tends to take root once it arises.

This seems hard to justify, though. Could something as complicated as magic arise from a single mutation? And if it’s not a single mutation, then we would not expect to see it popping up as often as we see Muggleborns.

So let’s move on from that theory. Suppose the magic genetics is not a single mutation, suppose it’s more complicated than that.

Leave aside the question of where wizards come from in the first place. Suppose that wizards have complicated genes for magic. Now where do Muggleborns come from, again?

Maybe a wizard charmed a few Muggle women, impregnated them, and left them to have children and spread magical genes around? But if it takes a lot of genes like that to be a full-blown wizard, you shouldn’t often see all of those genes assembling themselves together again.

One hypothesis that Harry considers is that there’s an engineered gene complex for magic, and it’s all on one chromosome.[23] This comes closer to potentially explaining what Harry already knows about in the way of observed magical population dynamics.

Perhaps a wizard charmed a few Muggle women, impregnated them, and left them to have their children. Then those children might have single copies of the magic chromosome. They’re Muggles, but they’re magic-carriers. And then perhaps some of those children marry other children like this, and maybe their children end up as wizards.

But the true answer according to my own worldbuilding, is that there isn’t a magic chromosome. There’s a Muggle chromosome! The default is magic. The universe must be magical at its core, because there’s a spell you can cast to create the appearance of mundanity, but from pure mundanity you can’t bootstrap to magic. Similarly: Sapient beings are magical by default, unless they have the Muggle chromosome that builds a circuit in their brain that uses their own magic to cancel out all their magic.

But sometimes the Muggle chromosome gets damaged via mutation. And that’s where Muggleborns come from in the general population.

This would even explain an observation that Draco Malfoy would’ve offered, and Harry from his own assumptions would’ve initially dismissed: Wizards with recent Muggleborn ancestry are more likely to give birth to Squibs. If the Muggle gene complex is complicated and fails upon small mutations or partial damage, then chromosomal crossover might sometimes repair that gene complex—especially if it’s a gene complex with only a small bit of damage, recently precipitated out of the Muggle population and gene pool.

But now we have a new question. Where did the Muggle gene complex come from?

Perhaps wizards do not have many kids and Muggles do, so a magic-dampening gene could be beneficial from an evolutionary perspective. And we do see in canon that an awful lot of wizards appear to be only children. But then we also see the Weasleys, so over thousands of years, it does not make sense that wizards have a heritable tendency to have fewer kids than Muggles.[24]

You can keep working at it, you can keep trying to rationalize the story for how a Muggle gene complex evolves. If the gene complex is complicated, it’s hard to make it work, though. And also you’re confined to one chromosome because there’s such a clear Mendelian pattern, as Harry observes in the story.

In any case, my own mental model as an author is that the Muggle chromosome is artificial. Somebody nerfed the magic abilities that every conscious being is otherwise born with, and built brains that use their magical abilities only to nullify their own magical abilities.

An Aside: What did Harry Figure Out?

Gretta: There’s a scene at the beginning of Chapter 25 in which Harry is trying to reason about magical genetics. First he (incorrectly) convinces himself that there’s a magic chromosome (not a Muggle chromosome). And then he thinks through the various implications, touching on Atlantis and the mechanisms by which magic spells are invoked. The line of reasoning ends:

The ancient forebears of the wizards, thousands of years earlier, had told the Source of Magic to only levitate things if you said...

‘Wingardium Leviosa.’

Harry slumped over at the breakfast table, resting his forehead wearily on his right hand.

When I read this, I didn’t really know what to make of it. I came away from this chapter still believing that there was a magic chromosome but that Harry was unhappy with some aspect of how it worked, or something. What was going on here?

Eliezer: You were not the only reader who was confused! Many people were confused. This was a learning moment for me as a writer.

When I wrote “Harry slumped over,” that was supposed to indicate that Harry was rejecting his own line of reasoning. If I could add one word to HPMOR, I would add the word “Contradiction” right after “Wingardium Leviosa.”

The idea here is that the timeline just clearly does not work out. A phrase like Wingardium Leviosa sounds Latin – but not like real Latin, like some kind of adulterated Latin with some other languages mixed into it. If it were real Latin it might be a couple of thousand years old, but with the “Wing” part, it sounds several hundred years old at best.

In Harry’s theory, magic dates back to the Atlanteans. He doesn’t know when they were around – they erased themselves from history, after all – but they were ancient, much more ancient than several hundred years.

One other piece of timeline evidence is the Sumerian Simple Strike Hex from chapter 16. You could figure out a way for the Sumerians to come before the Atlanteans, maybe, but it probably makes the most sense for the Atlanteans to come first, which would make them at least four to six thousand years old.

So why would the ancient Atlanteans program magic to be responsive to phrases that would not exist for several thousand years in their future?

They wouldn’t.

Harry realizes this and slumps over. He’s reached a logical dead end. But I needed to spell that out better, because many readers didn’t see the timeline problems and also didn’t infer that there was a dead end just from Harry’s body language.

Gretta: Yeah, I was probably never going to get that. I was treating Wingardium Leviosa as if it were real Latin, and could plausibly be 2500 years old or more. In retrospect I can see that the “Wing” part of it looks suspicious but I wasn’t focused on that.

Eliezer: Again, you were not alone!

Nested Nerfing Hypothesis

Eliezer: So now we have enough of the pieces that I can explain the Nested Nerfing Hypothesis.

Take the magical genetics we discussed.

Take the old wizard-philosophy idea I didn’t have time to introduce in-story, that the universe is fundamentally magical, and that the appearance of mundanity in large sections of itself must be a magical phenomenon laid on top of that; because if you start with magic you can cast a spell to produce the appearance of mundanity, but starting from mundanity there’s no way to get magic.

Take the story of Atlantis, which is more fanon than canon,[25] but then HPMOR is set in the world of fanon rather than canon to begin with. Atlantis previously reached the height of civilization. It was a powerful ancient wizarding society, and it fell. Why was it powerful, and why did it fall?

And then take the Interdict of Merlin.[26] Merlin put that into place, says HPMOR, because there was too much powerful destructive magic getting discovered and transmitted and popularized, and civilization was starting to totter.

And you arrive at a sort of possible picture for how the universe might have worked. Maybe the truth is that magic is powerful enough that it tends to destroy a lot of things. It is hard to keep the world in equilibrium when powerful magic is unchecked.

So perhaps there is a great cycle of history where over and over, magic comes close to destroying civilization, and then powerful wizards cast spells to nerf magic and save everyone.

But the nerfing is imperfect and more magic leaks through the cracks. Later generations of wizards find exploits and loopholes and they gain in power, until again the world is threatened and destabilized and again someone casts a nerfing spell.

Under the Nested Nerfing Hypothesis, the laws of physics themselves are just a spell. If it was just magic everywhere, things would fall apart too quickly. Some little piece of magic would blow up all the rest. So some magical Entity imposed the spell we know as the Mundane Laws of Physics, or maybe even it was an emergent sort of spell that just cast itself, back when there was too much magic happening all over.

But the laws of physics have flaws. The spell is imperfect. Magic leaks in around the edges.

In particular (the author is reasoning, behind the scenes), conscious sapient beings tend to end up with their own natural magic. There’s some kind of flaw in the Laws of Physics Spell. Either conscious sapient beings automatically have magic by default, or consciousness is derived from magic.

So somebody casts the spell that creates the Muggle chromosome, an added gene complex that automatically twists your natural magic in order to cancel itself. This prevents the proliferation of magical humans doing destructive magical things.. However, the Muggle chromosome, which is complex and easy to break, ends up with some mutations, and we get Squibs and wizards again rising from the Muggle population.

Atlantis comes into existence. They grow and gain in power… and then they erase themselves completely from time.

You now have a new non-magical population, ’cause most of the magical types killed themselves. The Muggle chromosome has more mutations. You get the medieval-era wizards. Their magic again gets too powerful. Merlin creates the Interdict of Merlin, which leads to the loss of magic over a certain power threshold.

Powerful wizards find various tiny cracks and loopholes in the Interdict of Merlin, ways to pass powerful magic on to each other. For example, the Slytherin Serpent, a very long lived creature that could tell some of the ancient secrets from one living soul to another.

And this is the Nested Nerfing Hypothesis — that the very strange world Harry finds himself in is the result of a series of attempted solutions to the problem of magic being too destructive. We slap a patch on that, the patch has holes, more magic comes into existence, another event happens that doesn’t completely destroy magic, and so on. And so this is the attempt to explain why the universe has the very odd, very weird form it does.

But ultimately the real answer is: because that’s what J. K. Rowling made up. Nothing can change this being the explanation that actually compresses the observations.

Epilogues

Gretta: What can you say about the status of the epilogue(s), by the way? Will we ever see them? What are they about? Are they good? Is it worth the wait? WHEN???

Eliezer: Right, so, the issue with the first epilogue is that I wrote it before I actually finished writing HPMOR proper, and by the time I got to the end of HPMOR, some things had changed and the tone had changed and the epilogue would’ve needed rewriting. And also, go figure, I was VERY burned out, and did not want to run off and rewrite that epilogue. Every year or two I take out the epilogue and try to rewrite it and fix the jarring tone problems, and every year so far, I’ve found that’s still been hard. Is the epilogue good? I think parts of it are good. That’s why I keep going back to it. It wraps up some things. It matters to me in terms of the artistic completeness of HPMOR. But I have not yet had the time, energy, and oomph to sit down and complete it. It is hard writing rather than easy writing.

On one of those occasions I did just go write a second epilogue and fully complete that one. I feel like it would arrive better after the first epilogue, even though Epilogue #1 takes place at the start of everyone’s seventh year (except Luna Lovegood, technically in her sixth), and Epilogue #2 takes place immediately after the end of HPMOR.

Possibly I will just end up releasing Epilogue #2 first, because #2 is complete and ready to go in all aspects except my own wish that I’d been able to redo Epilogue #1 and release that one first. If so, and if we can figure out how to do that, Epilogue #2 might get released before the book comes out. If it’s not out by September 16th, 2025, you may have to wait a while.

Why does nobody ever ask about the Project Lawful / Planecrash epilogue? I still have to finish that one too!

Thanks for reading, we hope you enjoyed this! And one final plea – please do consider pre-ordering If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies. Thank you!

- ^

The Real Story: The Gap into Conflict (2009)

- ^

Eliezer adds more context to the difference between drama and melodrama: “A drama is a play or a story and it can potentially be high prestige, whereas a melodrama is exaggerated, unsubtle, low status. Stephen R. Donaldson is offering a hypothesis about what distinguishes the shouty thing from the potentially subtle thing, though I do not think this is a full explanation of the difference, it’s just an aspect.”

- ^

Donaldson: “Melodrama presents a Victim, a Villain, and a Rescuer. Drama offers the same characters and then studies the process by which they change roles.”

- ^

Amusingly, if you read the afterword to Donaldson’s book, it is all about how frustrated Donaldson was with his attempts to implement the victim / villain / rescuer triangle in his writing. He wrote the story once, it came out extremely lopsided, he put it in a drawer for a few years. He rewrote it at least six times, trying to balance the triangle, but never quite got it up to his own standards. He writes, “And eventually I came to the conclusion that I was never going to be able to make it ‘aesthetically perfect.’ Judged by the standard of my original intentions, this book would always be a failure.”

- ^

Eliezer is correct that Orson Scott Card did say something like this in chapter eight of Writing Fantasy & Science Fiction:

“The most daring course, yet the one most likely to transform your audience, is to keep [the anti-hero] sympathetic throughout, while facing him with an opponent who is also sympathetic throughout the story. The audience will like both characters — a lot — and as [the anti-hero] and his opponent come into deadly conflict, your readers will be emotionally torn.

This is anguish, perhaps the strongest of emotions you can make your audience experience directly (as opposed to sympathetically mirroring what your characters feel). Neither character is at all confused about what he wants to have happen, yet your audience, emotionally involved with both of them, cannot bear to have either character lose. The emotional stakes are raised to much greater intensity, and yet the moral issues will again be removed from a matter of mere sympathy; in having to choose between characters they love, the readers will be forced to decide on the basis of the moral issues between them. Who really should prevail?”

- ^

For example, at the end of chapter 68:

”If I want to be a hero too,” said Hermione, “if I’ve decided to be a hero too, is there anything you can do to help?” - ^

This happens right after the previous citation, at the beginning of chapter 69.

- ^

OP = gamer slang for “overpowered”

- ^

There’s more about epilogues at the end of this article!

- ^

Eliezer remembers correctly! https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Sue

- ^

“Professor McGonagall was holding Hermione so firmly that you might have thought it was a mother holding her daughter, or maybe granddaughter.” – Chapter 81

- ^

For example: “Now what?” Dumbledore echoed. “Why, now the hero wins, of course.”

- ^

Hermione wakes up one morning in Chapter 72 and finds a “small slip of parchment” under her pillow telling her where to find a bully.

- ^

Nymphadora Tonks is metamorphagused into Susan Bones’ form.

- ^

Slashfic is fan-fiction jargon for a story that focuses on unconventional romantic or sexual pairings between characters, most often male-male pairings, that were not present in the original story.

- ^

In chapter 18, we see Snape being cruel, but we also learn that Snape is working with Dumbledore and McGonagall in the conspiracy — he is, in at least some senses, one of the good guys. And Harry infers that it is necessary, according to the tropes, to have an evil-seeming Potions professor, and Dumbledore allows him to believe that. As a result, Snape’s cruelty begins to look cooperative rather than insane, and it doesn’t serve as an adequate warm-up for Quirrell’s cruelty.

- ^

“Word of God” is fanfiction lingo for an authorial ruling on how to interpret ambiguous text; this is not Eliezer elevating himself to godhood.

- ^

- ^

- ^

The Oxford Languages / Google definition: “attempt to explain or justify (one’s own or another’s behavior or attitude) with logical, plausible reasons, even if these are not true or appropriate.”

- ^

Nerfing is gamer slang for taking something powerful and hobbling it to be much less powerful.

- ^

As a reminder, some terminology:

a wizard or witch is a magical person;

a Muggle is a non-magical person;

a Muggleborn is a wizard or witch who is born to Muggle parents;

a Squib is a person with at least one magical parent but who is themselves non-magical.

- ^

Harry tries hard to reason about this at the beginning of chapter 25. We’ll say more about what Harry figured out in the next section.

- ^

The Weasleys falsify that there is a limit of 1-2 children per magical family. The existence of the Weasleys says: “There is variance; small wizard families are not universal.” In evolutionary biology, the rate of evolution of anything is proportional to its variance (and equal to its heritable covariance with fitness). So when I look at the Weasleys, I see variance, and of course very direct covariance with fitness, with heritability not established but usually personality traits are partially heritable; and then my evolutionary biology goggles tell me, “Well, there’s variance (and covariance via sheer identity), so probably this characteristic will not change all that slowly.” So over a timespan of thousands of years, if there are any genes that produce heritable tendencies to have lots of kids like the Weasleys despite being a wizard, and there’s otherwise enough resources around to support those kids, there will be more and more Weasleys with large wizard families. “All the wizards just decide to have very few kids even though they could easily have more” is not something that explains the persistence of low wizard populations for thousands of years, because you’d have some wizards with a heritable tendency to have more kids than that.

- ^

For example, Harry Potter and the Wastelands of Time

- ^

“which stops anyone from getting knowledge of powerful spells out of books, even if you find and read a powerful wizard’s notes they won’t make sense to you, it has to go from one living mind to another.” (Chapter 23)

While I appreciate the existence of this post, and have upvoted it, I was a bit disappointed that virtually all the questions were about “get Eliezer to explain how Deeply Awesome the story was” and none of them challenged Eliezer in any way on areas of weakness in the story (or even areas of weakness in his own responses to some of the softball questions here).

I made a partial transcript of a WWMoR podcast episode with Eliezer from 2020, which included this part:

It’s hard to say what the largest literary flaw is. The story is a big mix of good and bad sides. But the final exam in particular felt weak to me even by its own standards: it’s not a good description of a difficult final encounter.

For me, the gold standard for a final encounter is the ending to the video game Veil of Darkness (I haven’t played it, but Ross Scott’s review recounts the whole thing). Basically we’re an average guy, and we need to defeat an elder vampire who had enslaved a valley of people for a thousand years and stolen all their sunlight. And here’s how the final battle goes: 1) we steal the vampire’s box containing all the stolen sunlight 2) we nail his coffin shut 3) wear a garlic necklace 4) eat a mushroom making us temporarily blind 5) confront him directly 6) he tries to mind-control us but fails due to our blindness 7) he tries to physically attack us but fails due to the necklace 8) we open the box with stolen sunlight at him, thus hitting him with an attack proportional to his age, nice detail isn’t it? 9) he staggers, turns into a bat and flies away to rest in the coffin 10) but the coffin is shut, so we finally stake him and cut off his head. There were a few other attacks too, but these are the main ones.

See what happened? The story makes the average guy defeating a thousand-year-old vampire sound actually believable. Because that’s how much work and preparation it takes to do something difficult. And this lesson you can apply in real life, unlike the lesson from HPMOR’s final exam.

I also criticized HPMOR’s Final Exam at the time, though for reasons of story consistency, rather than narrative.

That said, I don’t think the particular kind of satisfying conclusion you wanted to see works for rationalist fiction like HPMOR. After all, the premise is that all characters, protagonists and antagonists alike, have their own spark of optimization, genre savvy, and so on. So they know how these stories are supposed to go (the Hero wins, the Dark Lord loses, etc.), imagine how they could be defeated, and preempt those scenarios as best they can.

So in a rationalist version of that game finale, the elder vampire takes precautions against having his precious box stolen; protects his coffin from tampering; has overcome his weakness to garlic, or found a workaround (like a gust of wind spell or something), or faked having the weakness in the first place; etc. etc.

The most likely way for a prepared adversary to lose in such a situation is through a surprise, an out-of-sample error. That may not be as narratively satisfying, but it makes a lot more sense than for an elder vampire to die because an average human learned about his weaknesses. As if the vampire wasn’t aware of those weaknesses himself and didn’t have ample time to compensate for them.

An instructive (and fun) example is the case of Cazador Szarr (an antagonist in Baldur’s Gate 3).

(Spoilers, though not very important ones, below for anyone who hasn’t played BG3.)

Cazador is a vampire lord—old and very powerful. Astarion (one of the companion characters in the player’s party, and himself one of Cazador’s spawn, formerly[1] in the vampire lord’s thrall), in the course of telling the player character about Cazador (and explaining why Cazador never turns his spawn into full-fledged independent vampires—despite this being possible and indeed very easy—and instead keeps them as thralls under his absolute command), says that “the biggest threat to a vampire… is another vampire”.

In the normal course of events, it would be totally unbelievable for the player character to defeat Cazador. (Indeed, you would never even learn of his existence.) What makes Cazador’s downfall possible is the introduction of an Outside Context Problem, in the form of… well, the main plot device of the game.

However, the way things proceed is not just that Cazador is happily vampire-lording along, and then one day, bam! plot device’d right in the face! No, instead what happens is that the main plot device is injected into the normal state of affairs, things get shaken up, but what this does is allow for the possibility of Cazador being defeated, by radically changing the balance of forces in a way that he could not have foreseen. Then it’s up to the good guys (i.e., the player character & friends) to take advantage of being the right people in the right place at the right time, and exploit their sudden and temporary advantage, their brief window of opportunity, to take down Cazador.

Thus we get the best of both worlds: the enemy can be powerful and intelligent, but their defeat is nevertheless believable and satisfying.

It’s complicated.

Say a 1000 year old vampire that spent the first 500 years thinking of every possible adversary. They are well defended against anything that existed in the year 1500. Too bad they haven’t really kept up to date with modern tech.

Or, well most people don’t wear a bulletproof vest every day. Often cost and convenience trumps protection when people aren’t expecting to be attacked.

If a powerful antagonist is dumb or shortsighted enough, anyone can kill them, but what stories go out of their way to claim that their Big Bad is dumb? That’s usually the role of side characters or mooks, not of the Big Bad.

Plus it takes a certain kind of survival instinct to survive for 1000 years in the first place.

I agree with the tradeoff of safety vs. convenience, but there are many types of preparation that require a one-off investment, rather than an ongoing inconvenience. Cost, though, should not matter to most antagonists, since they typically far exceed the protagonists’ resources.

Hmm… this setup seems to cheat by withholding from vampires one of their most well-known and archetypal powers, namely the ability to turn into mist. (Dracula in Bram Stoker’s depiction can do this, vampires in D&D can do this, lots and lots of other examples.)

It also cheats by making the vampire stupid:

Why is the coffin in an accessible location—rather than, say, sealed away in a secret chamber that is accessible only via a small passage that can be navigated only by a creature the size of a bat? (Or, if we let the vampire have a mist form ability, a chamber accessible only via tiny, carefully concealed air holes, through which only a gaseous entity can pass.)

Why is there only one coffin, instead of several? (Once again, this particular failure mode is completely absent from Bram Stoker’s novel, for example, where Dracula, who needs to sleep in grave soil from the place where he was buried, has fifty containers of such soil distributed throughout the city; if one is compromised, well, he’ll just use the next one! Such tricks are likewise used by e.g. Strahd von Zarovich—D&D’s most famous vampire—and by many other fictional vampires.)

A thousand years is a long time to not have thought of such things…

Yeah. There were several other attacks that I omitted—something with holy water, something with a book, something with the vampire’s true name—maybe one of them did something about the mist form, or maybe not, I don’t know the lore that well tbh. And yeah, in a thousand years a vampire could probably figure out how to protect themselves pretty well, so to write a story where the average guy wins, there must be a bit of stretch somewhere. Anyway, my point is that this is still a more realistic depiction of how hard problems get solved. Or a more actionable one, at least.

Interestingly, this is another point in which Bram Stoker’s Dracula is very well thought-out. Stoker is well aware that with his rules, Dracula ought to be invincible… But Dracula has the liability that he’s been stultified mentally by centuries of quasi-imprisonment, and so hasn’t yet understood or experiments with his powers.

He is slowly waking up, and doing so, and starting to understand that he can eg. move his coffins himself without hirelings, but only right as the protagonists hunt him down. It is only by hours or minutes do they manage to cut him off from each resource. With another day or two, Dracula would have realized he could, say, just bury a bunch of coffins deep underground in the dirt, and he would be immune from discovery or attack.