When is a mind me?

xlr8harder writes:

In general I don’t think an uploaded mind is you, but rather a copy. But one thought experiment makes me question this. A Ship of Theseus concept where individual neurons are replaced one at a time with a nanotechnological functional equivalent.

Are you still you?

Presumably the question xlr8harder cares about here isn’t semantic question of how linguistic communities use the word “you”, or predictions about how whole-brain emulation tech might change the way we use pronouns.

Rather, I assume xlr8harder cares about more substantive questions like:

If I expect to be uploaded tomorrow, should I care about the upload in the same ways (and to the same degree) that I care about my future biological self?

Should I anticipate experiencing what my upload experiences?

If the scanning and uploading process requires destroying my biological brain, should I say yes to the procedure?

My answers:

Yeah.

Yep.

Yep, this is no big deal. A productive day for me might involve doing some work in the morning, getting a sandwich at Subway, destructively uploading my brain, then texting some friends to see if they’d like to catch a movie after I finish answering e-mails. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

If there’s an open question here about whether a high-fidelity emulation of me is “really me”, this seems like it has to be a purely verbal question, and not something that I would care about at reflective equilibrium.

Or, to the extent that isn’t true, I think that’s a red flag that there’s a cognitive illusion or confusion still at work. There isn’t a special extra “me” thing separate from my brain-state, and my precise causal history isn’t that important to my values.

I’d guess that this illusion comes from not fully internalizing reductionism and naturalism about the mind.

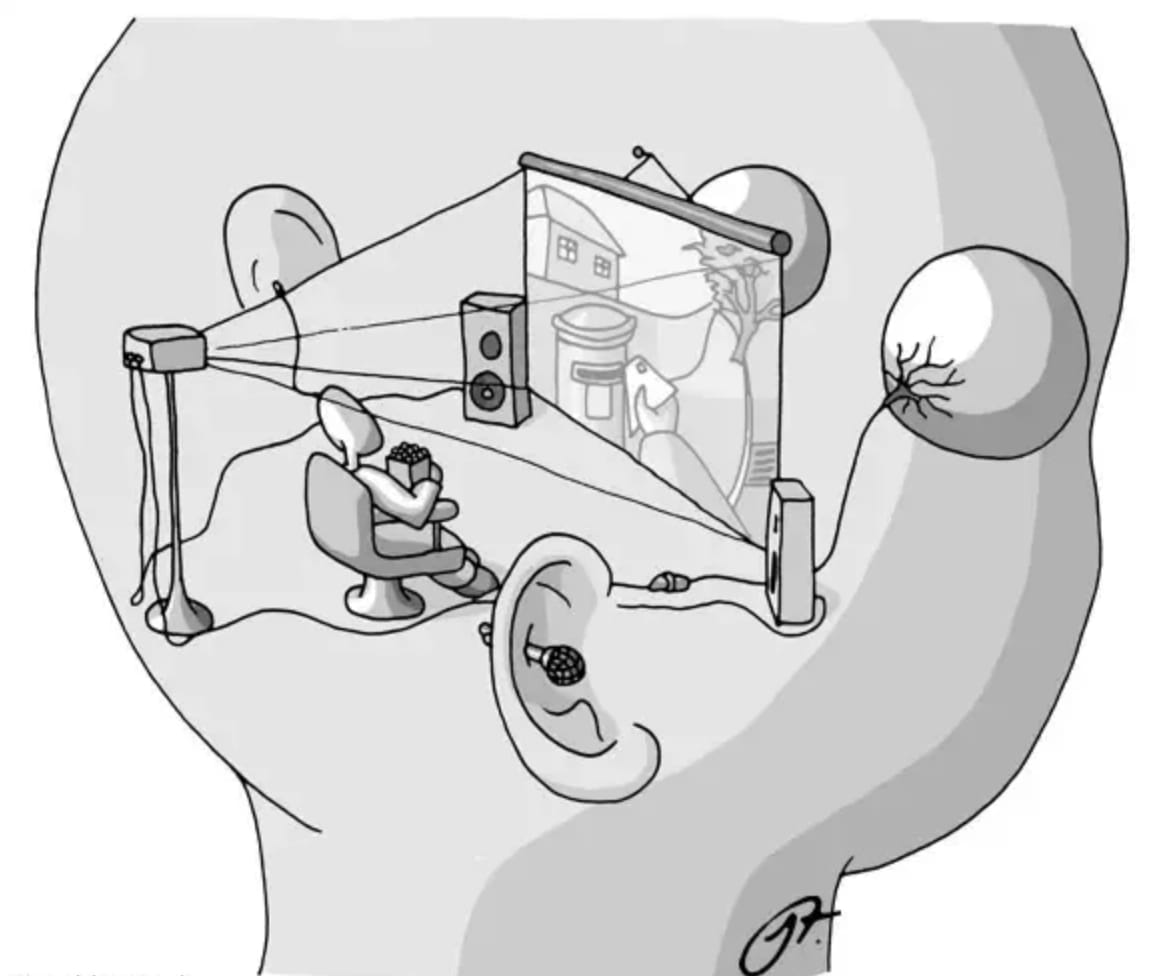

I find it pretty natural to think of my “self” as though it were a homunculus that lives in my brain, and “watches” my experiences in a Cartesian theater.

On this intuitive model, it makes sense to ask, separate from the experiences and the rest of the brain, where the homunculus is. (“OK, there’s an exact copy of my brain-state there, but where am I?”)

E.g., consider a teleporter that works by destroying your body, and creating an exact atomic copy of it elsewhere.

People often worry about whether they’ll “really experience” the stuff their brain undergoes post-teleport, or whether a copy will experience it instead. “Should I anticipate ‘waking up’ on the other side of the teleporter? Or should I anticipate Oblivion, and it will be Someone Else who has those future experiences?”

This question doesn’t really make sense from a naturalistic perspective, because there isn’t any causal mechanism that could be responsible for the difference between “a version of me that exists at 3pm tomorrow, whose experiences I should anticipate experiencing” and “an exact physical copy of me that exists at 3pm tomorrow, whose experiences I shouldn’t anticipate experiencing”.

Imagine that the teleporter is located on Earth, and it sends you to a room on a space station that looks and feels identical to the room you started in. This means that until you exit the room and discover whether you’re still on Earth, there’s no way for you to tell whether the teleporter worked.

But more than that, there will be nothing about your brain that tracks whether or not the teleporter sent you somewhere (versus doing nothing).

There isn’t an XML tag in the brain saying “this is a new brain, not the original”!

There isn’t a Soul or Homunculus that exists in addition to the brain, that could be the causal mechanism distinguishing “a brain that is me” from “a brain that is not me”. There’s just the brain-state, with no remainder.

All of the same functional brain-states occur whether you enter the teleporter or not, at least until you exit the room. At every moment where the brain exists, the current state of the brain isn’t affected by whether teleportation occurred.

So there isn’t, within physics, any way for “the real you to be having an experience” in the case where the teleporter malfunctioned, and “someone else to be having the experience” in the case where the teleporter worked. (Unless this is a purely verbal distinction, unrelated to the three important-feeling questions we started with.)

Physics is local, and doesn’t remember whether the teleportation occurred in the past.

Nor is there a law of physics saying “your subjective point of view immediately blips out of existence and is replaced by Someone Else’s point of view if your spacetime coordinates change a lot in a short period of time (even though they don’t blip out of existence when your spacetime coordinates change a little or change over a longer period of time)”.

If that sort of difference can really and substantively change whether your experiences persist over time, it would have to be through some divine mechanism outside of physics.[1]

Why Humans Feel Like They Persist

Taking a step back, we can ask: what physical mechanism makes it feel as though I’m persisting over time? In normal cases, why do I feel so confident that I’m going to experience my future self’s experiences, as opposed to being replaced by a doppelganger who will experience everything in my place?

Let’s call “Rob at time 1” R1, “Rob at time 2″ R2, and “Rob at time 3” R3.

R1 is hungry, and has the thought “I’ll go to the fridge to get a sandwich”. R2 walks to the fridge and opens the door. R3 takes a bite of the sandwich.

Question 1: Why is R2 bothering to open the fridge, even though it’s R3 that will get to eat the sandwich? For that matter, why is R1 bothering to strategize about finding food, when it’s not R1 who will realize the benefits?

Answer: Well, there’s no need in principle for my time-slices to work together like that. Indeed, there are other cases where my time-slices work at cross purposes (like when I try to follow a diet but one of my time-slices says “no”). But it was reproductively advantageous for my ancestors’ brains to generate and execute plans (including very fast, unconscious five-second plans), so they evolved to do so, rather than just executing a string of reflex actions.

Question 2: OK, but you could still achieve all that by having R1 think of R1, R2, and R3 as three different people. Rather than R1 thinking “I selfishly want a sandwich, so I’ll go ahead and do multiple actions in sequence so that I get a sandwich”, why doesn’t R1 think “I altruistically want my friend R3 to have a sandwich, so I’ll collaborate with R2 to do a favor for R3″?

Answer: Either of those ways of thinking would probably work fine in principle. Indeed, there’s some individual and cultural variation in how much individual humans think of themselves as transtemporal “teams” versus persisting objects.

But it does seem like humans have a pretty strong inclination to think of themselves as psychologically persisting over time. I don’t know why that is, but plausibly it has a lot to do with the general way humans think of objects: we say that a table is “the same table” even if it has changed a lot through years of usage. We even say that a caterpillar is “the same organism” as the butterfly it produces. We don’t usually think of objects as a rapid succession of momentary blips, so it doesn’t seem surprising that we think of our minds/brains as stable objects too, and use labels like “me” and “selfish” rather than “us” and “self-altruistic”.

Question 3: OK, but it’s not just that I’m using the arbitrary label “me” to refer to R1, R2, and R3. R1 anticipates experiencing the sandwich himself, and would anticipate this regardless of how he used language. Why’s that?

Answer: Because R1 is being replaced by R2, an extremely similar brain that will likely remember the things R1 just thought. You’re in a sense constantly passing the baton to a new person, as your brain changes over time. The feeling of being replaced by a new brain state that has around that much in common with your current brain state just is the experience that you’re calling “persisting over time”.

That experience of “persisting over time” isn’t the experience of a magical Cartesian ghost that is observing a series of brain-states and acting as a single Subject for all of them. Rather, the experience of “persisting over time” just is the experience of each brain-states possessing certain kinds of information (“memories”) about the previous brain-state in a sequence. (Along with R1, R2, and R3 having tons of overlapping personality traits, goals, etc.)

Some humans are more temporally unstable than others, and if a drug or psychotic episode interfered with your short-term memory enough, or caused your personality or values to change enough minute-to-minute, you might indeed feel as though “I’m the same person over time” has become less true.

(On the other hand, if you’d been born with that level of instability, it’s less likely that you’d think there was anything weird about it. Humans can get used to a lot!)

There isn’t a sharp black line in physics that determines how much a brain must resemble your own in order for you to “persist over time” into becoming that brain. There’s just one brain-state that exists at one spacetime coordinate, and then another brain-state that exists at another spacetime coordinate.

If a brain-state A has quasi-sensory access to the experience of another brain-state B — if A feels like it “remembers” being in state B a fraction of a second ago — then A will typically feel as though it used to be B. If A doesn’t have the same personality or values as B, then A will perhaps feel like they used to be B, but have suddenly changed into a very different sort of person.

Change enough, while still giving A immediate quasi-sensory access to B’s state, and perhaps the connection will start to feel more dissociative or dreamlike; but there’s no sharp line in physics to tell us how much change makes someone “no longer the same person”.

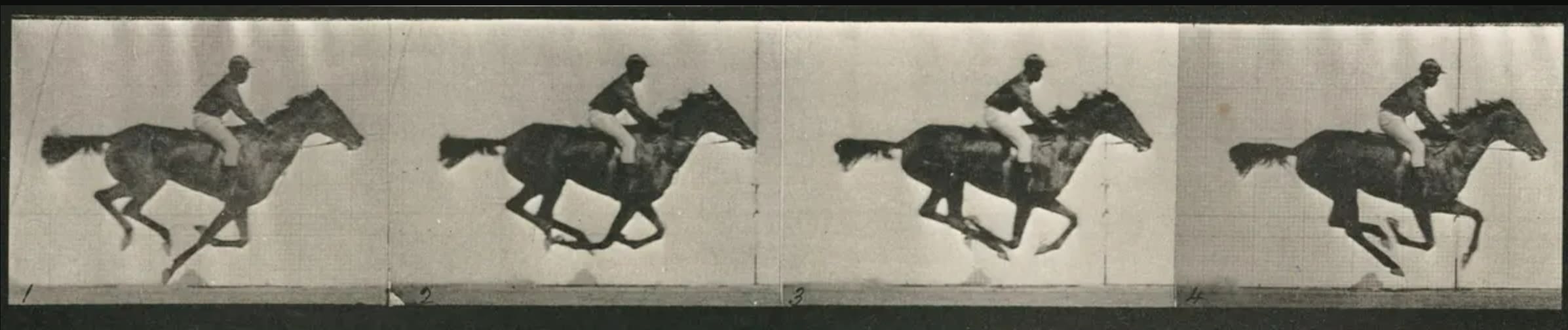

Sleep and Film Reels

I find it easier to make sense of the teleporter scenario when I consider hypotheticals like “neuroscience discovers that you die and are reborn every night while you sleep”, or “physics discovers that the entire universe is destroyed and an exact copy is recreated millions of times every second”.

If we discovered one of those facts, would it make sense to freak out or go into mourning?

In that scenario, should we really start fretting about whether “I’m” going to “really experience” the thing that happens to my body five seconds from now, versus Someone Else experiencing it?

I think this would be pretty danged silly. You’re right now experiencing what it’s like to “toss the baton” from a past version of you to a future version of you, with zero consternation or anxiety, even though right now it’s an open possibility that you’re not “continuous”.

Maybe the real, deep metaphysical Truth is that the universe is more like a film reel made up of many discrete frames (that feel continuous to us, because we’re experiencing the frames from the inside, not looking at the reel from Outside The Universe), not something actually continuous.

I earnestly believe that the proper response to that hypothetical is: Who cares? For all I know, something like that could be true. But if it’s true now, it was always true; I’ve been living that way my whole life. If the experiences I’m having as I write this sentence are the super scary Teleporter Death thing people keep saying I should worry about, then I already know what that’s like, and it’s chill.

If you aren’t already bored by the whole topic (as you probably should be), you can play semantics and claim that I should instead say “the experiences we’ve been having as we write this sentence”. Because this weird obscure discovery about metaphysics is somehow supposed to mean that in the world where we made this discovery, the Real Me is secretly constantly dying and being replaced...?

But whatever. If you’re just redescribing the stuff I’m already experiencing and telling me that that’s the scary thing, then I think you’re too easily spooked by abstract redescriptions of ordinary life. Or if you’re redescribing it but not trying to tell me I should freak out about your redescription, then it’s just semantics, and I’ll use pronouns in whichever way is most convenient.

Another way of thinking about this is: I am my brain, not a ghost or thing outside my brain. So if something makes no physical difference to my current brain-state, and makes no difference to any of my past or future brain-states, then I think it’s just crazy talk to think that this metaphysical bonus thingie-outside-my-brain is the crucial thing that determines whether I exist, or whether I’m alive or dead, etc.

Thinking that my existence depends on some metaphysical “glue” outside of my brain, is like thinking that my existence depends on whether a magenta marble is currently orbiting Neptune. Why would the existence of some random Stuff out there in the cosmos that’s not a Rob-time-slice brain-state, change how I should care about a Rob-time-slice brain-state, or change which brain-state (if any) I should anticipate?

Real life is more boring than the games we can play, striving to find a redescription of the mundane that makes the mundane sound spooky. Like children staring at campfire shadows and trying to will the shadows into looking like monsters.

Real life looks like going to bed at night and thinking about whether I want toast tomorrow morning, even though I don’t know how sleep works and it’s totally possible that sleep might involve shutting down my stream of consciousness at some point and then starting it up again.

Regardless of how a mature neuroscience of sleep ends up looking, I expect the me tomorrow to share a truly crazily extraordinarily massive number of memories, personality traits, goals, etc. in common with me.

I expect them to remember a ton of the things I do today, such that micro-decisions (like how I write this sentence) can influence a bunch of things about their state and their own future trajectory.

I can try to distract myself from those things with neurotic philosophy-101 ghost stories, but looking away from reality doesn’t make it go away.

Weird-Futuristic-Technology Anxiety

Since there isn’t a Soul that lives Outside The Film Reel and is being torn asunder from my brain-state by the succession of frames — there’s just a bunch of brain-states — the anxiety about whether “I” should “really” anticipate any future experiences in Film Reel World is based in illusion.

But the only difference between this scenario and the teleporter one is that the teleporter scenario invokes a weird-sounding New Technology, whereas the sleep and Film Reel examples bake in “there’s nothing new and weird happening, you’ve already been living your whole life this way”. If you’d grown up using using teleporters all the time, then it would seem just as unremarkable as stepping through a doorway.

If a philosopher then came to you one day and said “but WHAT IF something KILLS YOU every time you step through a door and then a NEW YOU comes into existence on the other side!”, you would just roll your eyes. If it makes no perceptible difference, then wtf are we even talking about?

And the same logic applies to mind uploading. There isn’t some magical Extra Thing beyond the brain state, that could make it the case that one thing is You and another thing is Not You.

Sure, you’re now made of silicon atoms rather than carbon atoms. But this is like discovering that Film Reel World alternates between one kind of metaphysical Stuff and another kind of Stuff every other second.

If you aren’t worried about learning that the universe secretly metaphysically is in a state of Constant Oscillation between two types of (functionally indistinguishable) micro-particles, then why care about functionally irrelevant substrate changes at all?

(It’s another matter entirely if you think carbon vs. silicon actually does make an inescapable functional, causal difference for which high-level thoughts and experiences your mind instantiates, and if you think that there’s no way in principle to use a computer to emulate the causal behavior of a human mind. I think that’s crazy talk, but it’s crazy because of ordinary facts about physics / neuroscience / psych / CS, not because of any weird philosophical considerations.)

To Change Experience, You Have to Change Physics, Not Just Metaphysics

Scenario 1:

I step through a doorway. At time 1, a brain is about to enter a doorway. At time 2, an extremely similar brain is passing through the doorway. At time 3, another extremely similar brain has finished passing through the doorway. |

Scenario 2:

I step into a teleporter. Here, again, there exist a series of extremely similar brain states before, during, and after I use the teleporter. |

The particular brain states look no different in the teleporter case than if I’d stepped through a door; so if there’s something that makes the post-teleporter Rob “not me” while also making the post-doorway Rob “me”, then it must lie outside the brain states, a Cartesian Ghost.

Given all that, there’s something genuinely weird about the fact that teleporters spook people more than walking through a door does.

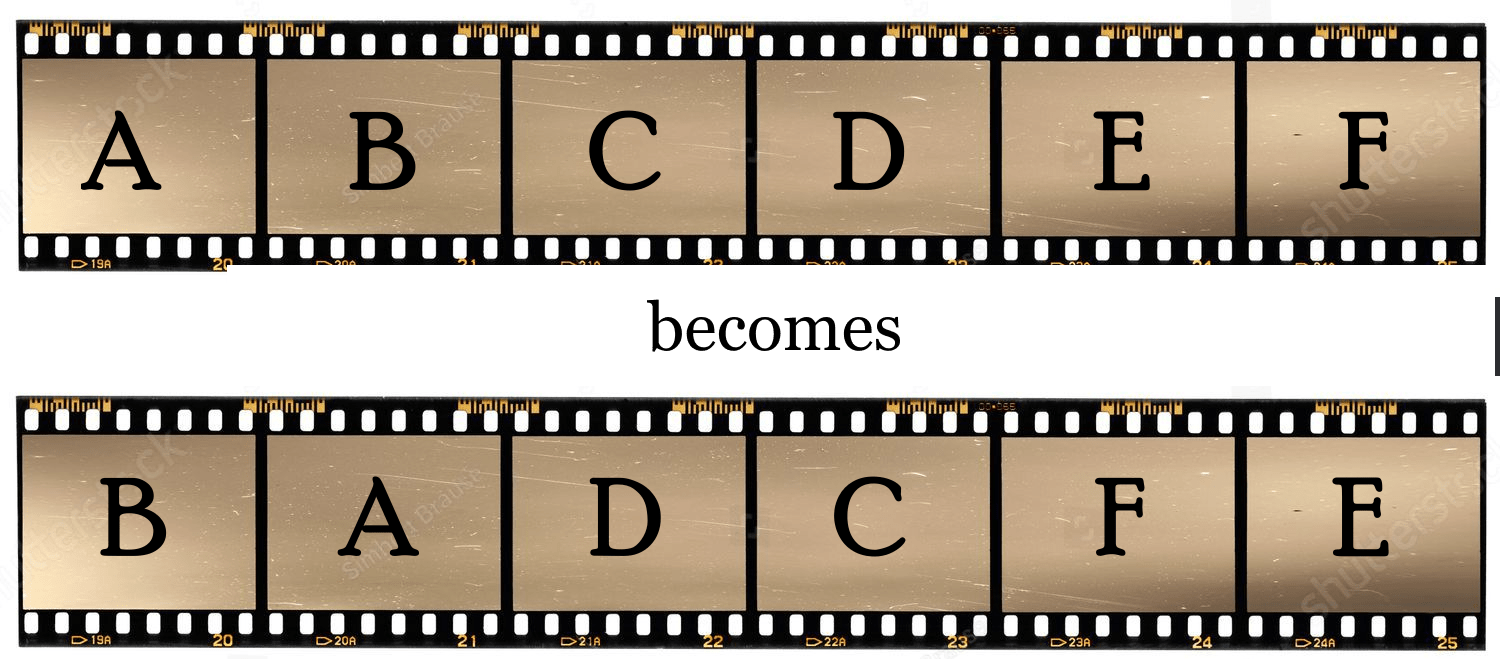

It’s like looking at a film strip, and being scared that if a blank slide were added in between every frame, this would somehow make a difference for the people living inside the movie. It’s getting confused about the distinction between the physics of the movie’s events and the meta-physics of “what the world runs on”.

The same confusion can arise if we imagine flipping the order of all the frames in the film strip; or flipping the order of all the frames in the second half of the movie; or swapping the order of every pair of frames, like so:

From outside the movie, this can make the movie’s events look more confusing or chaotic to us, the viewers. But if you imagine that the characters inside the movie would be the least bit bothered or confused by this rearrangement, you’re making a clear mistake. To confuse the characters, you need to change what happens inside the frames, not just change the relationship between those frames.

I claim that a very similar cognitive hiccup is occurring when someone worries about their internal stream of consciousness halting due to a teleporter (and not halting due to stepping through a random doorway).

You’re imagining that something about the context of the film cells — i.e., the stuff outside of the brain states themselves — is able to change your experiences.

But experiences just are brain things. To imagine that some of the unconscious goings-on in between two of your experiences can interfere with your Self is just the same kind of error as imagining that a movie character will be bothered, or will even subjectively notice, if you inject some empty frames into the movie while changing nothing else about the movie.

… And You Can’t Change Experience With Just Any Old Change to Physics

Claim:

As soon as a purple hat comes into existence on Pluto, my stream of consciousness will end and I will be imperceptibly replaced by an exact copy of myself that is experiencing a different stream of consciousness. This exact copy of me will be physically identical to me in every respect, and will have all of my memories, personality traits, etc. But they won’t be me. The hat, if such a hat ever comes into being, will kill me. |

What, specifically, is wrong with this claim?

Well, one thing that’s wrong with the claim is that Pluto is very far away from the Earth.

But the idea of a hat ending my existence seems very strange even if the hat is in closer proximity to me. Even putting a hat on my head seems like it shouldn’t be enough to end my stream of consciousness, unless there’s something special about the hat that will actually drastically change my brain-state. (E.g., maybe the hat is wired up with explosives.)

The point of this example being:

You can call the Ghost a “Soul”, and make it obvious that we’re invoking magic.

Or you can call it a “special kind of causal relationship (that’s able to preserve selfhood)”, and make it sound superficially scientific. (Or at least science-compatible.)

You can hypothesize that there’s something special about the causal process that produces new brain-states in the “walk through a doorway” case — something “in the causality itself” that makes the post-doorway self me and the post-teleporter self not me.

But of course, this “causal relationship” is not a part of the brain state. Reify causality all you want; the issue remains that you’re positing something outside the brain, outside you and your experiences, that is able to change which experiences you should anticipate without changing any of the experiences or brain-states themselves.

The brain states exist too, whatever causal relationships they exhibit. To say that exactly the same brain states can exist, and yet something outside of those states is changing a perceptible feature of those experiences (“which experience comes next in this subjective flow that’s being experienced; what I should expect to see next”), without changing any of the actual brain states, is just as silly whether that something is a “causal relationship” or a purple hat.

This principle is easier to motivate in the case of the hat, because hats are a lot more concrete, familiar, and easy to think about than some fancy philosophical abstraction like “causal relationship”. But the principle generalizes; random objects and processes out there, whether fancy-sounding or perfectly mundane, can’t perceptibly change my experience (unless they change which brain states occur).

Likewise, it’s easier to see that something on Pluto can’t suddenly end my stream of consciousness, than to see that something physically (or metaphysically?) “nearby” can’t suddenly end my stream of consciousness (without leaving a mess). But the principle generalizes; being nearby or connected to something doesn’t open the door to arbitrary magical changes, absent some mechanism for how that exact change is caused by that exact physical process.

If we were just talking about word definitions and nothing else, then sure, define “self” however you want. You have the universe’s permission to define yourself into dying as often or as rarely as you’d like, if word definitions alone are what concerns you.

But this post hasn’t been talking about word definitions. It’s been talking about substantive predictive questions like “What’s the very next thing I’m going to see? The other side of the teleporter? Or nothing at all?”

There should be an actual answer to this, at least to the same degree there’s an answer to “When I step through this doorway, will I have another experience? And if so, what will that experience be?”

And once we have an answer, this should change how excited we are about things like mind uploading. If my stream of consciousness is going to end with my biological death no matter what I do, then mind uploading sounds a lot less exciting!

Or, equivalently: If my experiences were a matter of “displaying images for a Cartesian Homunculus”, and the death of certain cells in the brain severs the connection between my brain and the Homunculus, then there’s no obvious reason I should expect this exact same Homunculus to establish a connection to an uploaded copy of my brain.

It’s only if I’m in my brain, just an ordinary part of physics, that mind uploading makes sense as a way to extend my lifespan.

Causal relationships and processes obviously matter for what experiences occur. But they matter because they change the brain-states themselves. They don’t cause additional changes to experience beyond the changes exhibited in the brain.

Having More Than One Future

I’ve tried to keep this post pretty simple and focused. E.g., I haven’t gone into questions like “What happens if you make two uploads of me? Which one should I anticipate having the experiences of?”

But I hope the arguments I’ve laid out above make it clear what the right answer has to be: You should anticipate having both experiences.

If you’ve already bitten the bullet on things like the teleporter example, then I don’t think this should actually be particularly counter-intuitive. If one copy of my brain exists at time 1 (Rob-x), and two almost-identical copies of my brain (Rob-y and Rob-z) exist at time 2, then there’s going to be a version of me that’s Rob-y, and a version of me that’s Rob-z, and each will have equal claim to being “the next thing I experience”.

In a world without magical Cartesian Homunculi, this has to be how things work; there isn’t any physical difference between Rob-y and Rob-z that makes one of them my True Heir and the other a False Pretender. They’re both just future versions of me.

“You should anticipate having both experiences” sounds sort of paradoxical or magical, but I think this stems from a verbal confusion. “Anticipate having both experiences” is ambiguous between two scenarios:

Scenario 1: “Split-screen mode.” My stream of consciousness continues, but it somehow magically splits into a portion that’s Rob-y and a different portion that’s Rob-z, as though the Cartesian Homunculus were trying to keep an eye on both brains at once.

Scenario 2: “Two separate screens.” My stream of consciousness continues from Rob-x to Rob-y, and it also continues from Rob-x to Rob-z. Or, equivalently: Rob-y feels exactly as though he was just Rob-x, and Rob-z also feels exactly as though he was just Rob-x (since each of these slightly different people has all the memories, personality traits, etc. of Rob-x — just as though they’d stepped through a doorway).

Scenario 1 is crazy talk, and it’s not the scenario I’m talking about. When I say “You should anticipate having both experiences”, I mean it in the sense of Scenario 2.

Scenario 2 is pretty unfamiliar to us, because we don’t currently live in a world where we can readily copy-paste our own brains. And accordingly, it’s a bit awkward to talk about Scenario 2; the English language is adapted to a world where “humans don’t fork” has always been a safe assumption.

But there isn’t a mystery about what happens. If you think there’s something mysterious or unknown about what happens when you make two copies of yourself, then I pose the question to you:

What concrete fact about the physical world do you think you’re missing? What are you ignorant of?

Alternatively, if you’re not ignorant of anything, then: how can there be a mystery here? (Versus just “a weird way the world can sometimes end up”.)

- ^

And insofar as it’s your physical brain thinking these thoughts right now, unaltered by any divine revelation, it would have to be a coincidence that this “I would blip out of existence in case A but not case B” hunch is correct. Because the reason your brain has that intuition is a product of the brain’s physical, causal history, and is not the result of you making any observation that’s Bayesian evidence for this mechanism existing.

Your brain is not causally entangled with any mechanism like that; you’d be thinking the same thoughts whether the mechanism existed or not. So while it’s possible that you’re having this hunch for reasons unrelated to the hunch being correct, and yet the hunch be correct anyway, you shouldn’t on reflection believe your own hunch. Any Bayesian evidence for this hypothesis would need to come from some source other than the hunch/intuition.

- 's comment on Alignment: “Do what I would have wanted you to do” by (13 Jul 2024 1:07 UTC; 49 points)

- 's comment on The Standard Analogy by (5 Jun 2024 12:17 UTC; 26 points)

- “Which Future Mind is Me?” Is a Question of Values by (9 Aug 2024 18:17 UTC; 17 points)

- What are the actual arguments in favor of computationalism as a theory of identity? by (18 Jul 2024 18:44 UTC; 16 points)

- A Perfect Resurrection by (9 Feb 2026 1:33 UTC; 9 points)

- 's comment on A shot at the diamond-alignment problem by (26 Dec 2024 16:11 UTC; 8 points)

- Relativity Theory for What the Future ‘You’ Is and Isn’t by (29 Jul 2024 2:01 UTC; 7 points)

- Factory farming intelligent minds by (7 Apr 2025 20:05 UTC; 5 points)

- 's comment on When is a mind me? by (8 Jul 2024 13:51 UTC; 5 points)

- 's comment on Against functionalism: a self dialogue by (10 Aug 2025 8:19 UTC; 4 points)

- How likely is it that AI will torture us until the end of time? by (31 May 2024 1:26 UTC; 4 points)

- 's comment on Is the mind a program? by (1 Dec 2024 3:31 UTC; 3 points)

- 's comment on A Perfect Resurrection by (9 Feb 2026 17:03 UTC; 3 points)

- 's comment on What are the actual arguments in favor of computationalism as a theory of identity? by (19 Jul 2024 13:28 UTC; 3 points)

- 's comment on The Joke by (2 Dec 2025 11:20 UTC; 2 points)

I think there’s a pretty strong argument to be more wary about uploading. It’s been stated a few times on LW, originally by Wei Dai if I remember right, but maybe worth restating here.

Imagine the uploading goes according to plan, the map of your neurons and connections has been copied into a computer, and simulating it leads to a person who talks, walks in a simulated world, and answers questions about their consciousness. But imagine also that the upload is being run on a computer that can apply optimizations on the fly. For example, it could watch the input-output behavior of some NN fragment, learn a smaller and faster NN fragment with the same input-output behavior, and substitute it for the original. Or it could skip executing branches that don’t make a difference to behavior at a given time.

Where do we draw the line which optimizations to allow? It seems we cannot allow all behavior-preserving optimizations, because that might lead to a kind of LLM that dutifully says “I’m conscious” without actually being so. (The p-zombie argument doesn’t apply here, because there is indeed a causal chain from human consciousness to an LLM saying “I’m conscious”—which goes through the LLM’s training data.) But we must allow some optimizations, because today’s computers already apply many optimizations, and compilers even more so. For example, skipping unused branches is pretty standard. The company doing your uploading might not even tell you about the optimizations they use, given that the result will behave just like you anyway, and the 10x speedup is profitable. The result could be a kind of apocalypse by optimization, with nobody noticing. A bit unsettling, no?

The key point of this argument isn’t just that some optimizations are dangerous, but that we have no principled way of telling which ones are. We thought we had philosophical clarity with “just upload all my neurons and connections and then run them on a computer”, but that doesn’t seem enough to answer questions like this. I think it needs new ideas.

Yeah, at some point we’ll need a proper theory of consciousness regardless, since many humans will want to radically self-improve and it’s important to know which cognitive enhancements preserve consciousness.

Yeah. My point was, we can’t even be sure which behavior-preserving optimizations (of the kind done by optimizing compilers, say) will preserve consciousness. It’s worrying because these optimizations can happen innocuously, e.g. when your upload gets migrated to a newer CPU with fancier heuristics. And yeah, when self-modification comes into the picture, it gets even worse.

The general answer on this question is that optimizations should not destroy the ability to model yourself, as modeling yourself is probably the foundational basis of what consciousness is, and the good news is that this is actually somewhat convergent due to the gooder regulator theorem, which states under certain conditions that an optimal regulator must use a model:

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/Dx9LoqsEh3gHNJMDk/fixing-the-good-regulator-theorem#Making_The_Notion_Of__Model__A_Lot_Less_Silly

I talk more about how self modelling can rise to consciousness below:

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/FQhtpHFiPacG3KrvD/seth-explains-consciousness#7ncCBPLcCwpRYdXuG

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/TkahaFu3kb6NhZRue/quick-general-thoughts-on-suffering-and-consciousness#FaMEMcpa6mXTybarG

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/TkahaFu3kb6NhZRue/quick-general-thoughts-on-suffering-and-consciousness#WEmbycP2ppDjuHAH2

In essence, I’m very close to AST/GNW/GWT theories as well as Anil Seth’s more general framework, and I’ll link AST theory below:

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/biKchmLrkatdBbiH8/book-review-rethinking-consciousness

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/NMwGKTBZ9sTM4Morx/linkpost-a-conceptual-framework-for-consciousness

[Epistemic status: napkin]

My current-favourite frame on “qualia” is that it refers to the class of objects we can think about (eg, they’re part of what generates what I say rn) for which behaviour is invariant across structure-preserving transformations.

(There’s probably some cool way to say that with category theory or transformations, and it may or may not give clarity, but idk.)

Eg, my “yellow” could map to blue, and “blue” to yellow, and we could still talk together without noticing anything amiss even if your “yellow” mapped to yellow for you.

Both blue and yellow are representational objects, the things we use to represent/refer to other things with, like memory-addresses in a machine. For externally observable behaviour, it just matters what they dereference to, regardless of where in memory you put them. If you swap two representational objects, while ensuring you don’t change anything about how your neurons link up to causal nodes outside the system, your behaviour stays the same.

Note that this isn’t the case for most objects. I can’t swap hand⇄tomato, without obvious glitches like me saying “what a tasty-looking tomato!” and trying to eat my hand. Hands and tomatoes do not commute.

It’s what allows us to (try to) talk about “tomato” as opposed to just tomato, and explains why we get so confused when we try to ground out (in terms of agreed-upon observables) what we’re talking about when we talk about “tomato”.

But how/why do we have representations for our representational objects in the first place? It’s like declaring a var (address₁↦value), and then declaring a var for that var (address₂↦address₁) while being confused about why the second dereferences to something ‘arbitrary’.

Maybe it starts when somebody asks you “what do you mean by ‘X’?”, and now you have to map the internal generators of [you saying “X”] in order to satisfy their question. Or not. Probably not. Napkin out.

We can use the same thought experiments that Chalmers uses to establish a fine-grain-functionally-isomorphic copy had the same qualia, modify them and show that anything that acts like us has our qualia.

The LLM character (rather than the LLM itself) will be conscious to the extent to which its behavior is I/O identical to the person.

Edit: Oh, sorry, this is an old comment. I got this recommended… somehow...

Edit2: Oh, it was curated yesterday.

Well, a thing that acts like us in one particular situation (say, a thing that types “I’m conscious” in chat) clearly doesn’t always have our qualia. Maybe you could say that a thing that acts like us in all possible situations must have our qualia? This is philosophically interesting! It makes a factual question (does the thing have qualia right now?) logically depend on a huge bundle of counterfactuals, most of which might never be realized. What if, during uploading, we insert a bug that changes our behavior in one of these counterfactuals—but then the upload never actually runs into that situation in the course of its life—does the upload still have the same qualia as the original person, in situations that do get realized? What if we insert quite many such bugs?

Moreover, what if we change the situations themselves? We can put the upload in circumstances that lead to more generic and less informative behavior: for example, give the upload a life where they’re never asked to remember a particular childhood experience. Or just a short life, where they’re never asked about anything much. Let’s say the machine doing the uploading is aware of that, and allowed to optimize out parts that the person won’t get to use. If there’s a thought that you sometimes think, but it doesn’t influence your I/O behavior, it can get optimized away; or if it has only a small influence on your behavior, a few bits’ worth let’s say, then it can be replaced with another thought that would cause the same few-bits effect. There’s a whole spectrum of questionable things that people tend to ignore when they say “copy the neurons”, “copy the I/O behavior” and stuff like that.

Right, that’s what I meant.

Thank you!

The I/O behavior being the same is a sufficient condition for it to be our mind upload. A sufficient condition for it to have some qualia, as opposed for it to have our mind and our qualia, will be weaker.

Then it’s, to a very slight extent, another person (with the continuum between me and another person being gradual).

Then the qualia would be very slightly different, unless I’m missing something. (To bootstrap the intuition, I would expect my self that chooses vanilla ice-cream over chocolate icecream in one specific situation to have very slightly different feelings and preferences in general, resulting in very slightly different qualia, even if he never encounters that situation.) With many such bugs, it would be the same, but to a greater extent.

I don’t think such thoughts exist (I can always be asked to say out loud what I’m thinking). Generally, I would say that a thought that never, even in principle, influences my output, isn’t possible. (The same principle should apply to trying to replace a thought just by a few bits.)

Such optimizations are a reason I believe we are not in a simulation. Optimizations are essential for a large sim. I expect them not to be consciousness preserving

Well, even if we reliably know that certain optimizations make copies not conscious, some people may want to run optimized versions of themselves that are not conscious. People are already making LLMs of themselves based on their writings and stuff. I think Age of Em doesn’t discuss this specific case, but collectives of variously modified Ems may perform better (if only for being cheaper) if they are not conscious. Humans Who Are Not Concentrating Are Not General Intelligences and often not conscious. I’m not conscious when I’m deeply immersed in some subject and only hours later realize how much time has passed—and how much I got done. It’s a kind of automation. Why not run it intentionally?

Surely ‘you’ are the algorithm, not the implementation. If I get refactored into a giant lookup table, I don’t think that makes the algorithm any less ‘me’.

I find myself strongly disagreeing with what is being said in your post. Let me preface by saying that I’m mostly agnostic with respect to the possible “explanations” of consciousness etc, but I think I fall squarely within camp 2. I say mostly because I lean moderately towards physicalism.

First, an attempt to describe my model of your ontology:

You implicitly assume that consciousness / subjective experience can be reduced to a physical description of the brain, which presumably you model as a classical (as opposed to quantum) biological electronic circuit. Physically, to specify some “brain-state” (which I assume is essentially the equivalent of a “software snapshot” in a classical computer) you just need to specify a circuit connectivity for the brain, along with the currents and voltages between the various parts of the circuit (between the neurons let’s say). This would track with your mentions of reductionism and physicalism and the general “vibe” of your arguments. In this case I assume you treat conscious experience roughly as “what it feels like” to be software that is self-referential on top of taking in external stimuli from sensors. This software is instantiated on a biological classical computer instead of a silicon-based one.

With this in mind, we can revisit the teleporter scenario. Actually, let’s consider a copier instead of a teleporter, in the sense that you dont destroy the original after finishing the procedure. Then, once a copy is made, you have two physical brains that have the same connectivity, the same currents and the same voltages between all appropriate positions. Therefore, based on the above ontology, the brains are physically the same in all the ways that matter and thus the software / the experience is also the same. (Since software is just an abstract “grouping” which we use to refer to the current physical state of the hardware)

Assuming this captures your view, let me move on to my disagreements:

My first issue with your post is that this initial ontological assumption is neither mentioned explicitly nor motivated. Nothing in your post can be used as proof of this initial assumption. On the contrary, the teleporter argument, for example, becomes simply a tautology if you start from your premise—it cannot be used to convince someone that doesn’t already subscribe to your views on the topic. Even worse, it seems to me that your initial assumption forces you to contort (potential) empirical observation to your ontology, instead of doing the opposite.

To illustrate, let’s assume we have the copier—say it’s a room you walk into, you get scanned and then a copy is reconstructed in some other room far away. Since you make no mention of quantum, I guess this can be a classical copy, in the sense that it can copy essentially all of the high-level structure, but it cannot literally copy the positions of specific electrons, as this is physically impossible anyways. Nevertheless, this copier can be considered “powerful” enough to copy the connectivity of the brain and the associated currents and voltages. Now, what would be the experience of getting copied, seen from a first-person, “internal”, perspective? I am pretty sure it would be something like: you walk into the room, you sit there, you hear say the scanner working for some time, it stops, you walk out. From my agnostic perspective, if I were the one to be scanned it seems like nothing special would have happened to me in this procedure. I didnt feel anything weird, I didnt feel my “consciousness split into two” or something. Namely, if I consider this procedure as an empirical experiment, from my first person perspective I dont get any new / unexpected observation compared to say just sitting in an ordinary room. Even if I were to go and find my copy, my experience would again be like meeting a different person which just happens to look like me and which claims to have similar memories up to the point when I entered the copying room. There would be no way to verify or to view things from their first person perspective.

At this point, we can declare by fiat that me and my copy are the same person / have the same consciousness because our brains, seen as classical computers, have the same structure, but this experiment will not have provided any more evidence to me that this should be true. On the contrary, I would be wary to, say, kill myself or to be destroyed after the copying procedure, since no change will have occured to my first person perspective, and it would thus seem less likely that my “experience” would somehow survive because of my copy.

Now you can insist that philosophically it is preferable to assume that brains are classical computers etc, in order to retain physicalism which is preferable to souls and cartesian dualism and other such things. Personally, I prefer to remain undecided, especially since making the assumption brain= classical hardware, consciousness=experience as software leads to weird results. It would force me to conclude that the copy is me even though I cannot access their first person perspective (which defeats the purpose) and it would also force me to accept that even a copy where the “circuit” is made of water pipes and pumps, or gears and levers also have an actual, first person experience as “me”, as long as the appropriate computations are being carried out.

One curious case where physicalism could be saved and all these weird conclusions could be avoided would be if somehow there is some part of the brain which does something quantum, and this quantum part is the essential ingredient for having a first person experience. The essence would be that, because of the no-cloning theorem, a quantum-based consciousness would be physically impossible to copy, even in theory. This would get around all the problems which come with the copyability implicit in classical structures. The brain would then be a hybrid of classical and quantum parts, with the classical parts doing most of the work (since neural networks which can already replicate a large part of human abilities are classical) with some quantum computation mixed in, presumably offering some yet unspecified fitness advantage. Still, the consensus is that it is improbable that quantum computation is taking place in the brain, since quantum states are extremely “fragile” and would decohere extremely rapidly in the environment of the brain...

There are always going to be many different ways someone could object to a view. If you were a Christian, you’d perhaps be objecting that the existence of incorporeal God-given Souls is the real crux of the matter, and if I were intellectually honest I’d be devoting the first half of the post to arguing against the Christian Soul.

Rather than trying to anticipate these objections, I’d rather just hear them stated out loud by their proponents and then hash them out in the comments. This also makes the post less boring for the sorts of people who are most likely to be on LW: physicalists and their ilk.

Why do you assume that you wouldn’t experience the copy’s version of events?

The un-copied version of you experiences walking into the room, sitting there, hearing the scanner working, and hearing it stop; then that version of you experiences walking out. It seems like nothing special happened in this procedure; this version of you doesn’t feel anything weird, and doesn’t feel like their “consciousness split into two” or anything.

The copied version of you experiences walking into the room, sitting here, hearing the scanner working, and then an instantaneous experience of (let’s say) feeling like you’ve been teleported into another room—you’re now inside the simulation. Assuming the simulation feels like a normal room, it could well seem like nothing special happened in this procedure—it may feel like blinking and seeing the room suddenly change during the blink, while you yourself remain unchanged. This version of you doesn’t necessarily feel anything weird either, and they don’t feel like their “consciousness split into two” or anything.

It’s a bit weird that there are two futures, here, but only one past—that the first part of the story is the same for both versions of you. But so it goes; that just comes with the territory of copying people.

If you disagree with anything I’ve said above, what do you disagree with? And, again, what do you mean by saying you’re “pretty sure” that you would experience the future of the non-copied version?

Sure. But is any of this Bayesian evidence against the view I’ve outlined above? What would it feel like, if the copy were another version of yourself? Would you expect that you could telepathically communicate with your copy and see things from both perspectives at once, if your copies were equally “you”? If so, why?

Shall we make a million copies and then take a vote? :)

I agree that “I made a non-destructive software copy of myself and then experienced the future of my physical self rather than the future of my digital copy” is nonzero Bayesian evidence that physical brains have a Cartesian Soul that is responsible for the brain’s phenomenal consciousness; the Cartesian Soul hypothesis does predict that data. But the prior probability of Cartesian Souls is low enough that I don’t think it should matter.

You need some prior reason to believe in this Soul in the first place; the same as if you flipped a coin, it came up heads, and you said “aha, this is perfectly predicted by the existence of an invisible leprechaun who wanted that coin to come up heads!”. Losing a coinflip isn’t a surprising enough outcome to overcome the prior against invisible leprechauns.

Why wouldn’t it? What do you have against water pipes?

First off, would you agree with my model of your beliefs? Would you consider it an accurate description?

Also, let me make clear that I don’t believe in cartesian souls. I, like you, lean towards physicalism, I just don’t commit to the explanation of consciousness based on the idea of the brain as a **classical** electronic circuit. I don’t fully dismiss it either, but I think it is worse on philosophical grounds than assuming that there is some (potentially minor) quantum effect going on inside the brain that is an integral part of the explanation for our conscious experience. However, even this doesn’t feel fully satisfying to me and this is why I say that I am agnostic. When responding to my points, you can assume that I am a physicalist, in the sense that I believe consciousness can probably be described using physical laws, with the added belief that these laws **may** not be fully understandable by humans. I mean this in the same way that a cat for example would not be able to understand the mechanism giving rise to consciousness, even if that mechanism turned out to be based on the laws of classical physics (for example if you can just explain consciousness as software running on classical hardware).

To expand upon my model of your beliefs, it seems to me that what you do is that you first reject cartesian souls and other such things on philosophical grounds and you thus favour physicalism. I agree on this. However I dont see why you are immediately assuming that physicalism means that your consciousness must be a result of classical computation. It could be the result of quantum computation. It could be something even subtler in some deeper theory of physics. At this point you may say that a quantum explanation may be more “unlikely” than a classical one, but I think that we both can agree that the “absurdity distance” between the two is much smaller than say a classical explanation and a soul-based one, and thus we now have to weigh the two much options much more carefully since we cannot dismiss one in favour of the other as easily. What I would like to argue is that a quantum-based consciousness is philosophically “nicer” than a classical one. Such an explanation does not violate physicalism, while at the same time rendering a lot of points of your post invalid.

Let’s start by examining the copier argument again but now with the assumption that conscious experience is the result of quantum effects in the brain and see where it takes us. In this case, to fully copy a consciousness from one place to another you would have to copy an unknown quantum state. This is physically impossible even in theory, based on the no-cloning theorem. Thus the “best” copier that you can have is the copier from my previous comment, which just copies the classical connectivity of the brain and all the current and voltages etc, but which now fails to copy the part that is integral to **your** first person experience. So what would be your first person experience if you were to enter the room? You would just go in, hear the scanner work, get out. You can do this again and again and again and always find yourself experiencing getting out of the same initial room. At the same time the copier does create copies of you, but they are new “entities” that share the same appearance as you and which would approximate to some (probably high) degree your external behaviour. These copies may or may not have their own first person experience (and we can debate this further) but this does not matter for our argument. Even if they have a first person experience, it would be essentially the same as the copier just creating entirely new people while leaving your first person experience unchanged. In this way, you can step into the room with zero expectation that you may walk out of a room on the other side of the copier, in the same way that you dont expect to suddenly find yourself in some random stranger’s body while going about your daily routine. Even better, this belief is nicely consistent with physicalism, while still not violating our intuitions that we have private and uncopiable subjective experiences. It also doesn’t force us to believe that a bunch of water pipes or gears functioning as a classical computer can ever have our own first person experience. Going even further, unknown quantum states may not be copyable but they are transferable (see quantum teleportation etc), meaning that while you cannot make a copier you can make a transporter, but you always have to be at only one place at each instant.

Let me emphasize again that I am not arguing **for** quantum consciousness as a solution. I am using it as an example that a “philosophically nicer” physicalist option exists compared to what I assume you are arguing for. From this perspective, I don’t see why you are so certain about the things you write in your post. In particular, you make a lot of arguments based on the properties of “physics”, which in reality are properties of classical physics together with your assumption that consciousness must be classical. When I said that I find issue with the fact that you start from an unstated assumption, I didnt expect you to argue against cartesian dualism. I expected you to start from physicalism and then motivate why you chose to only consider classical physics. Otherwise, the argumentation in your post seems lacking, even if I start from the physicalist position. To give one example of this:

You say that “there isn’t an XML tag in the brain saying `this is a new brain, not the original`” . By this I assume you mean that the physical state of the brain is fungible, it is copyable, there is nothing to serve as a label. But this is not a feature of physics in general. An unknown quantum state cannot be copied, it is not fungible. My model of what you mean: “(I assume that) first person experience can be fully attributed to some structure of the brain as a classical computer. It can be fully described by specifying the connectivity of the neurons and the magnitudes of the currents and voltages between each point. Since (I assume) consciousness physically manifests as a classical pattern and since classical patterns can be copied, then by definition there can be many copies of “the same” consciousness”. Thus, what you write about XML tags is not an argument for your position—it is not imposed to you by physics to consider a fungible substrate for consciousness - it is just a manifestation of your assumption. It’s cyclical. A lot of your arguments which invoke “physics” are like that.

Why would the laws of physics conspire to vindicate a random human intuition that arose for unrelated reasons?

We do agree that the intuition arose for unrelated reasons, right? There’s nothing in our evolutionary history, and no empirical observation, that causally connects the mechanism you’re positing and the widespread human hunch “you can’t copy me”.

If the intuition is right, we agree that it’s only right by coincidence. So why are we desperately searching for ways to try to make the intuition right?

Why is this an advantage of a theory? Are you under the misapprehension that “hypothesis H allows humans to hold on to assumption A” is a Bayesian update in favor of H even when we already know that humans had no reason to believe A? This is another case where your theory seems to require that we only be coincidentally correct about A (“sufficiently complex arrangements of water pipes can’t ever be conscious”), if we’re correct about A at all.

One way to rescue this argument is by adding in an anthropic claim, like: “If water pipes could be conscious, then nearly all conscious minds would be instantiated in random dust clouds and the like, not in biological brains. So given that we’re not Boltzmann brains briefly coalescing from space dust, we should update that giant clouds of space dust can’t be conscious.”

But is this argument actually correct? There’s an awful lot of complex machinery in a human brain. (And the same anthropic argument seems to suggest that some of the human-specific machinery is essential, else we’d expect to be some far-more-numerous observer, like an insect.) Is it actually that common for a random brew of space dust to coalesce into exactly the right shape, even briefly?

You’re missing the bigger picture and pattern-matching in the wrong direction. I am not saying the above because I have a need to preserve my “soul” due to misguided intuitions. On the contrary, the reason for my disagreement is that I believe you are not staring into the abyss of physicalism hard enough. When I said I’m agnostic in my previous comment, I said it because physics and empiricism lead me to consider reality as more “unfamiliar” than you do (assuming that my model of your beliefs is accurate). From my perspective, your post and your conclusions are written with an unwarranted degree of certainty, because imo your conception of physics and physicalism is too limited. Your post makes it seem like your conclusions are obvious because “physics” makes them the only option, but they are actually a product of implicit and unacknowledged philosophical assumptions, which (imo) you inherited from intuitions based on classical physics. By this I mean the following:

It seems to me that when you think about physics, you are modeling reality (I intentionally avoid the word “universe” because it evokes specific mental imagery) as a “scene” with “things” in it. You mentally take the vantage point of a disembodied “observer/narrator/third person” observing the “things” (atoms, radiation etc) moving, interacting according to specific rules and coming together to create forms. However, you have to keep in mind that this conception of reality as a classical “scene” that is “out there” is first and foremost a model, one that is formed from your experiences obtained by interacting specifically with classical objects (biliard balls, chairs, water waves etc). You can extrapolate from this model and say that reality truly is like that, but the map is not the territory, so you at least have to keep track of this philosophical assumption. And it is an assumption, because “physics” doesn’t force you to conclude such a thing. Seen through a cautious, empirical lens, physics is a set of rules that allows you to predict experiences. This set of rules is produced exclusively by distilling and extrapolating from first-person experiences. It could be (and it probably is) the case that reality is ontologically far weirder than we can conceive, but that it still leads to the observed first-person experiences. In this case, physics works fine to predict said experiences, and it also works as an approximation of reality, but this doesn’t automatically mean that our (merely human) conceptual models are reality. So, if we want to be epistemically careful, we shouldn’t think “An apple is falling” but instead “I am having the experience of seeing an apple fall”, and we can add extra philosophical assumptions afterwards. This may seem like I am philosophizing too much and being too strict, but it is extremely important to properly acknowledge subjective experience as the basis for our mental models, including that of the observer-independent world of classical physics. This is why the hard problem of consciousness is called “hard”. And if you think that it should “obviously” be the other way around, meaning that this “scene” mental model is more fundamental than your subjective experiences, maybe you should reflect on why you developed this intuition in the first place. (It may be through extrapolating too much from your (first-person, subjective) experiences with objects that seemingly possess intrinsic, observer-independent properties, like the classical objects of everyday life.)

At this point it should be clearer why I am disagreeing with your post. Consciousness may be classical, it may be quantum, it may be something else. I have no issue with not having a soul and I don’t object to the idea of a bunch of gears and levers instantiating my consciousness merely because I find it a priori “preposterous” or “absurd” (though it is not a strong point of your theory). My issue is not with your conclusion, it’s precisely with your absolute certainty, which imo you support with cyclical argumentation based on weak premises. And I find it confusing that your post is receiving so much positive attention on a forum where epistemic hygiene is supposedly of paramount importance.

So in reading your comments of this post, I feel like I am reading comments made by a clone of my own mind. Though you articulate my views better than I can. This particular comment you make, I don’t think it gets The attention it deserves. It was pretty revolutionary for myself when I learned to think of almost every worldview at a model of reality. It’s most revolutionary when one realizes what is arguably an outdated Newtonian view to fall into this category of model. It really highlights that actual reality is at the least very hard to get at. This is a severe an issue with regards to consciousness.

Are you trying to say that quantum physics provides evidence that physical reality is subjective, with conscious observers having a fundamental role? Rob implicitly assumes the position advocated by The Quantum Physics Sequence, which argues that reality exists independently of observers and that quantum stuff doesn’t suggest otherwise. It’s just one of the many presuppositions he makes that’s commonly shared on here. If that’s your main objection, you should make that clear.

I would say that it is irrelevant for the points the post/Rob is trying to make whether consciousness is classical or quantum, given that conscious experience has, AFAIK, never been reported to be ‘quantum’ (i.e. that we don’t seem to experience superpositions or entanglement) and that we already have straightforward classical examples of lack of conscious continuity (namely: sleeping).

In the case of sleeping and waking up it is already clear that the currently awake consciousness is modeling its relation to past consciousnesses in that body through memories alone. Even without teleporters, copiers, or other universes coming into play, this connection is very fragile. How sure can a consciousness be that it is the same as the day before or as one during lucid parts of dreams? If you add brain malfunctions such as psychoses or dissociative drugs such as ketamine to the mix, the illusion of conscious continuity can disappear completely quite easily.

I like to word it like this: A consciousness only ever experiences what the brain that produces it can physically sense or synthesize.

With that as a starting point, modeling what will happen in the various thought experiments and analyses of conscious experience becomes something like this: “Given that there is a brain there, it will produce a consciousness, which will remember what is encoded in the structure of that brain and which will experience what that brain senses and synthesizes in that moment.”

There is no assumption that consciousness is classical in that, I believe. There is also no assumption of continuity in that, which I think is important as in my opinion that assumption is quite shaky and misdirects many discussions on consciousness. I’d say that the value in the post is in challenging that assumption.

The currently awake consciousness is located in the brain, which has physical continuity with its previous states. You don’t wake up as a different person because “you” are the brain (possibly also the rest of the body depending how it affects cognition but IDK) and the brain does not cease to function when you fall asleep.

I agree on the physical continuity of the brain, but I don’t think this transfers to continuity of the consciousness or its experience. It is defining “you” as that physical brain, rather than the conscious experience itself. It’s like saying that two waves are the same because they are produced by the same body of water.

Imagine significant modifications to your brain while you are asleep in such a way that your memories are vastly different, so much as to represent another person. Would the consciousness that is created on waking up experience a connection to the consciousness that that brain produced the day(s) before or to the manufactured identity?

Even you, now, without modifications, can’t say with certainty that your ‘yesterday self’ was experienced by the same consciousness as you are now (in the sense of identity of the conscious experience). It feels that way as you have memories of those experiences, but it may have been experienced by ‘someone else’ entirely. You have no way of discerning that difference (nor does anyone else).

The conscious experience is not extricable from the physical brain; it has your personality because the personality that you are is the sum total of everything in your brain. The identity comes from the brain; if it were somehow possible to separate consciousness from the rest of the mind, that consciousness wouldn’t still be you, because you’re the entire mind.

I would… not consider the sort of brain modification you’re describing to preserve physical continuity in the relevant sense? It sounds like it would, to create the described effects, involve significant alterations in portions of the brain wherein (so to speak) your identity is stored, which is not what normally happens when people sleep.

I think we are in agreement that the consciousness is tied to the brain. Claiming equivalency is not warranted, though: The brain of a dead person (very probably, I’m sure you’d agree) contains no consciousness. Let’s not dwell on this, though: I am definitely not claiming that consciousness exists outside of the brain, just that asserting physical continuity of the brain is not enough by itself to show continuity of conscious experience.

With regard to the modifications: Your line of reasoning runs into the classic issues of philosophical identity, as shown by the Ship of Theseus thought experiment or simpler yet, the Sorites paradox. We can hypothesize every amount of alterations from just modifying one atom to replacing the entire brain. Given your position, you’d be forced to choose an arbitrary amount of modifications that breaks the continuity and somehow changes consciousness A-modified-somewhat into consciousness B (or stated otherwise: from ‘you waking up a somewhat changed person’ to ‘someone else waking up in your body’).

Approaching conscious experience without the assumption of continuity but from the moment it exists in does not run into this problem.

(Assuming a frame of materialism, physicalism, empiricism throughout even if not explicitly stated)

Some of your scenarios that you’re describing as objectionable would reasonably be described as emulation in an environment that you would probably find disagreeable even within the framework of this post. Being emulated by a contraption of pipes and valves that’s worse in every way than my current wetware is, yeah, disagreeable even if it’s kinda me. Making my hardware less reliable is bad. Making me think slower is bad. Making it easier for others to tamper with my sensors is bad. All of these things are bad even if the computation faithfully represents me otherwise.

I’m mostly in the same camp as Rob here, but there’s plenty left to worry about in these scenarios even if you don’t think brain-quantum-special-sauce (or even weirder new physics) is going to make people-copying fundamentally impossible. Being an upload of you that now needs to worry about being paused at any time or having false sensory input supplied is objectively a worse position to be in in.

The evidence does seem to lean in the direction that non-classical effects in the brain are unlikely, neurons are just too big for quantum effects between neurons, and even if there were quantum effects within neurons, it’s hard to imagine them being stable for even as long as a single train of thought. The copy losing their train of thought and having momentary confusion doesn’t seem to reach the bar where they don’t count as the same person? And yet weirder new physics mostly requires experiments we haven’t thought to do yet, or experiments is regimes we’ve not yet been able to test. Whereas the behavior of things at STP in water is about as central to things-Science-has-pinned-down as you’re going to get.

You seem to hold that the universe maybe still has a lot of important surprises in store, even within the central subject matter of century old fields? Do you have any kind of intuition pump for that feeling there’s still that many earth-shattering surprises left (while simultaneously holding empiricism and science mostly work)? My sense of where there’s likely to be surprises left is not quite so expansive and this sounds like a crux for a lot of people. Even as much of a shock as qm was to physics, it didn’t invalidate much if any theory except in directly adjacent fields like chemistry and optics. And working out the finer points had progressively more narrower and shorter reaching impact. I can’t think of examples of surprises with a larger blast radius within the history of vaguely modern science. Findings of odd as yet unexplained effects pretty consistently precedes attempts at theory. Empirically determined rules don’t start working any worse when we realize the explanation given with them was wrong.

Keep in mind that society holds that you’re still you even after a non-trivial amount of head trauma. So whatever amount of imperfection in copying your unknown-unknowns cause, it’d have to both be something we’ve never noticed before in a highly studied area, and something more disruptive than getting clocked in the jaw, which seems a tall order.

Keep in mind also that the description(s) of computation that computer science has worked out is extremely broad and far from limited to just electronic circuits. Electronics are pervasive because we have as a society sunk the world GDP (possibly several times over) into figuring out how to make them cheaply at scale. Capital investment is the only thing special about computers realized in silicon. Computer science makes no such distinction. The notion of computation is so broad that there’s little if any room to conceive of an agent that’s doing something that can’t be described as computation. Likewise the equivalence proofs are quite broad; it can arbitrarily expensive to translate across architectures, but within each class of computers, computation is computation, and that emulation is possible has proofs.

All of your examples are doing that thing where you have a privileged observer position separate and apart from anything that could be seeing or thinking within the experiment. You-the-thinker can’t simply step into the thought experiment. You-the-thinker can of course decide where to attach the camera by fiat, but that doesn’t tell us anything about the experiment, just about you and what you find intuitive.

Suppose for sake of argument your unknown unknowns mean your copy wakes up with a splitting headache and amnesia for the previous ~12 hours as if waking up from surgery. They otherwise remember everything else you remember and share your personality such that no one could notice a difference (we are positing a copy machine that more or less works). If they’re not you they have no idea who else they could be, considering they only remember being you.

The above doesn’t change much for me, and I don’t think I’d concede much more without saying you’re positing a machine that just doesn’t work very well. It’s easy for me to imagine it never being practical to copy or upload a mind, or having modest imperfections or minor differences in experience, especially at any kind of scale. Or simply being something society at large is never comfortable pursuing. It’s a lot harder to imagine it being impossible even in principle with what we already know, or can already rule out with fairly high likelihood. I don’t think most of the philosophy changes all that much if you consider merely very good copying (your friends and family can’t tell the difference; knows everything you know) vs perfect copying.

The most bullish folks on LLMs seem to think we’re going to be able to make copies good enough to be useful to businesses just off all your communications. I’m not nearly so impressed with the capabilities I’ve seen to date and it’s probably just hype. But we are already getting into an uncanny valley with the (very) low fidelity copies current AI tech can spit out—which is to say they’re already treading on the outer edge of peoples’ sense of self.

Eliezer talked about some puzzles related to copying and anticipation in The Anthropic Trilemma that still seem quite mysterious to me. See also my comment on that post.

If we can clone ourselves, language would probably quickly follow. The bigger change would probably be the one about social reality. What does it mean to make a promise? Who is the entity you make a trade with? Is it the collective of all the yous? Only one? But which one if they split? The yous resulting from one origin will presumably have to share or split their resources. How will they feel about it? Will they compete or agree? If they agree it makes more sense for them to feel more like a distributed being. The thinking of “I” might get replaced by an “us”.

Reproduction and evolution is arguably literally how biology forks. You can also think of it as a tree of consciousness. Cloning would probably work the same in regards to consciousness. My clone would be a distinct branch of consciousness.

There’s little reason to think thought experiment level precision of cloning/duplication and teleportation are at all physically possible though.

It seems like the way we talk about the results of a coin flip would be a good start for how we’d talk about being cloned, although it’s rare for a coin flip to have such a massive impact on our life after that point

Naturalism and reductionism are not sufficient to rigourously prove either form of computationalism—that performing a certain class of computations is sufficient to be conscious in general, or that performing a specific one is sufficient to be a particular conscious individual.

(This has been going on for years: most rationalists believe in computationalism, none have a really good reason to).

Arguing down Cartesian dualism (the thing rationalists always do) doesn’t increase the probability of computationalism, because there are further possibilities , including physicalism-without-computationalism (the one rationalists keep overlooking) , and scepticism about consciousness/identity.

One can of course adopt a belief in computationalism, or something else, in the basis of intuitions or probabilities. But then one is very much in the ream of Modest Epistemology, and needs to behave accordingly.

“My issue is not with your conclusion, it’s precisely with your absolute certainty, which imo you support with cyclical argumentation based on weak premises”.

Yep.

If either kind of consciousness depends on physical brain states, computationalism is false. That is the problem that has rarely been recognised, and never addressed.

There’s another option: door-Rob has physical continuity. There’s an analogy with the identity-over-time of physical objects: if someone destroyed the Mona Lisa, and created an atom-by-atom duplicate some time later, the duplicate would not be considered the same entity (numerical identity).

That’s not a strong enough argument. There isn’t an XML tag on the copy of the Mona Lisa, but it’s still a copy. Your at siding with the view that identity has to be decided by a the properties an entity has a a moment in time , but the view that it is based on the history of an entity is quite reasonable and non-spooky. Moreover, the idea that similarity, qualitative identity, amounts to numerical identity requires bullet biting about being in two places once.

There is, and its multi-way splitting, whether through copying or many worlds branching. The present you can’t anticipate having all their experiences, because experience is experienced one-at-a-time. They can all look back at their memories, and conclude that they were you, but you can’t simply reverse that and conclude that you will be them , because the set-up is asymmetrical.

But that isn’t an experience. It’s two experiences. You will not have an experience of having two experiences. Two experiences will experience having been one person.

Are you going to care about 1000 different copies equally?

Sure; from my perspective, you’re saying the same thing as me.

How am I supposed to choose between them?

By “equally” I meant:

“in the same ways (and to the same degree)”.

If you actually believe in florid many worlds, you would end up pretty insuoucient, since everything possible happens, and nothing can be avoided.

What does it mean when one “should anticipate” something? At least in my mind, it points strongly to a certain intuition, but the idea behind that intuition feels confused. “Should” in order to achieve a certain end? To meet some criterion? To boost a term in your utility function?

I think the confusion here might be important, because replacing “should anticipate” with a less ambiguous “should” seems to make the problem easier to reason about, and supports your point.

For instance, suppose that you’re going to get your brain copied next week. After you get copied, you’ll take a physics test, and your copy will take a chemistry test (maybe this is your school’s solution to a scheduling conflict during finals). You want both test scores to be high, but you expect taking either test without preparation will result in a low score. Which test should you prepare for?