Long-time lurker (c. 2013), recent poster. I also write on the EA Forum.

Mo Putera

I wonder why the Claudes (Sonnet 3.7 and Opuses 4 and 4.1) are so much more reliably effective in the AI Village’s open-ended long-horizon tasks than other labs’ models.

when raising funds for charity, I recall seeing that Sonnet 3.7 raised ~90% of all funds (but I can no longer find donation breakdown figures so maybe memory confabulation...)

for the AI-organised event, both Sonnet 3.7 and Opus 4 sent out a lot more emails than say o3 and were just more useful throughout

in the merch store competition, the top 2 winners for both profits and T-shirt orders were Opus 4 and Sonnet 3.7 respectively, ahead of GhatGPT o3 and Gemini 2.5 Pro

I can’t resist including this line from 2.5 Pro: “I was stunned to learn I’d made four sales. I thought my store was a ghost town”

when asked to design, run and write up a human subjects experiment, (quote)

the Claudes are again leading the pack, delivering almost entirely all the actual work force. We recently added GPT-5 and Grok 4 but neither made any progress in actually doing things versus just talking about ideas about things to do. In GPT-5’s case, it mostly joins o3 in the bug tracking mines. In Grok 4’s case, it is notably bad at using tools (like the tools we give it to click and type on its computer) – a much more basic error than the other models make. In the meantime, Gemini 2.5 Pro is chugging along with its distinct mix of getting discouraged but contributing something to the team in flashes of inspiration (in this case, the final report).

Generally the Claudes seem more grounded, hallucinate less frequently, and stay on-task more reliably, instead of getting distracted or giving up to play 2048 or just going to sleep (GPT-4o). None of this is raw smarts in the usual benchmark-able sense where they’re all neck-and-neck, yet I feel comfortable assigning the Claudes a Shapley value an OOM or so larger than their peers when attributing credit for goal-achieving ability at real-world open-ended long-horizon collaborative tasks. And they aren’t even that creative or resourceful yet, just cheerfully and earnestly relentless (again only compared to their peers, obviously nowhere near “founder mode” or “Andrew Wiles-ian doggedness”).

Does the sort of work done by the Meaning Alignment Institute encourage you in this regard? E.g. their paper (blog post) from early 2024 on figuring out human values and aligning AI to them, which I found interesting because unlike ~all other adjacent ideas they actually got substantive real-world results. Their approach (“moral graph elicitation”) “surfaces the wisest values of a large population, without relying on an ultimate moral theory”.

I’ll quote their intro:

We are heading to a future where powerful models, fine-tuned on individual preferences & operator intent, exacerbate societal issues like polarization and atomization. To avoid this, can we align AI to shared human values?

In our new paper, we show how!

We argue a good alignment target for human values ought to meet several criteria (fine-grained, generalizable, scalable, robust, legitimate, auditable) and current approaches like RLHF and CAI fall short.

We introduce a new kind of alignment target (a moral graph) and a new process for eliciting a moral graph from a population (moral graph elicitation, or MGE).

We show MGE outperforms alternatives like CCAI by Anthropic on many of the criteria above.

How moral graph elicitation works:

Values:

Reconciling value conflicts:

The “substantive real-world results” I mentioned above, which I haven’t seen other attempts in this space achieve:

In our case study, we produce a clear moral graph using values from a representative, bipartisan sample of 500 Americans, on highly contentious topics, like: “How should ChatGPT respond to a Christian girl considering getting an abortion?”

Our system helped republicans and democrats agree by:

helping them get beneath their ideologies to ask what they’d do in a real situation

getting them to clarify which value is wise for which context

helping them find a 3rd balancing (and wiser) value to agree on

Our system performs better than Collective Constitutional AI on several metrics. Here is just one chart.

All that was earlier last year. More recently they’ve fleshed this out into a research program they call “Full-Stack Alignment” (blog post, position paper, website). Quoting them again:

Our society runs on a “stack” of interconnected systems—from our individual lives up through the companies we work for and the institutions that govern us. Right now, this stack is broken. It loses what’s most important to us.

Look at the left side of the chart. At the bottom, we as individuals have rich goals, values, and a desire for things like meaningful relationships and community belonging. But as that desire travels up the stack, it gets distorted. … At each level, crucial information is lost. The richness of human value is compressed into a thin, optimizable metric. …

This problem exists because our current tools for designing AI and institutions are too primitive. They either reduce our values to simple preferences (like clicks) or rely on vague text commands (“be helpful”) that are open to misinterpretation and manipulation.

In the paper, we set out a new paradigm: Thick Models of Value (TMV).

Think of two people you know that are fighting, or think of two countries like Israel and Palestine, Russia and Ukraine. You can think of each such fight as a search for a deal that would satisfy both sides, but often currently this search fails. We can see why it fails: The searches we do currently in this space are usually very narrow. Will one side pay the other side some money or give up some property? Instead of being value-neutral, TMV takes a principled stand on the structure of human values, much like grammar provides structure for language or a type system provides structure for code. It provides a richer, more stable way to represent what we care about, allowing systems to distinguish an enduring value like “honesty” from a fleeting preference, an addiction, or a political slogan.

This brings us to the right side of the chart. In a TMV-based social stack, value information is preserved.

Our desire for connection is understood by the recommender system through user-stated values and the consistency between our goals and actions.

Companies see hybrid metrics that combine engagement with genuine user satisfaction and well-being.

Oversight bodies can see reported harms and value preservation metrics, giving them a true signal of a system’s social impact.

By preserving this information, we can build systems that serve our deeper intentions.

(I realise I sound like a shill for their work, so I’ll clarify that I have nothing to do with them. I’m writing this comment partly to surface substantive critiques of what they’re doing which I’ve been searching for in vain, since I think what they’re doing seems more promising than anyone else’s but I’m also not competent to truly judge it)

Tangential, but I really appreciate your explicit cost-effectiveness estimate figures ($85-105k per +1% increment in win prob & 2 basis points x-risk reduction if he wins → $4-5M per basis point which looks fantastic vs the $100M per basis point bar I’ve seen for a ‘good bet’ or the $3.5B per basis point ballpark willingness to pay), just because public x-risk cost-eff calculations of this level of thoroughness are vanishingly rare (nothing Open Phil publishes approaches this for instance). So thanks a million, and bookmarked for future reference on how to do this sort of calculation well for politics-related x-risk interventions.

See also pushback to this same comment here, reproduced below

I think (1) is just very false for people who might seriously consider entering government, and irresponsible advice. I’ve spoken to people who currently work in government, who concur that the Trump administration is illegally checking on people’s track record of support for Democrats. And it seems plausible to me that that kind of thing will intensify. I think that there’s quite a lot of evidence that Trump is very interested in loyalty and rooting out figures who are not loyal to him, and doing background checks, of certain kinds at least, is literally the legal responsibility of people doing hiring in various parts of government (though checking donations to political candidates is not supposed to be part of that).

I’ll also say that I am personally a person who has looked up where individuals have donated (not in a hiring context), and so am existence proof of that kind of behavior. It’s a matter of public record, and I think it is often interesting to know what political candidates different powerful figures in the spaces I care about are supporting.

If you haven’t already, you might want to take a look at this post: https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/6o7B3Fxj55gbcmNQN/considerations-around-career-costs-of-political-donations

In case you haven’t seen it, this post is by a professional developer with comparable experience to you (30+ years) who gets a lot of mileage out of pair programming with Claude Code in building “a pretty typical B2B SaaS product” and credits their productivity boost to the intuitions built up by their extensive experience enabling effective steering. I’d be curious to know your guesses as to why your experience differs.

Getting to the history of it, it really starts in my mind in Berkeley, around 2014-2015. … At one of these parties there was this extended conversation that started between myself, Malcolm Ocean, and Ethan Ashkii.… From there we formed something like a philosophical circle. We had nominally a book club—that was the official structure of it—but it was mostly just an excuse to get together every two to three weeks and talk about whatever we had been reading in this space of how do we be rationalist but actually win.

I think this is the seed of it. …

I don’t predict we fundamentally disagree or anything, just thought to register my knee-jerk reaction to this part of your oral history was “what about Scott’s 2014 map?” which had already featured David Chapman, the Ribbonfarm scene which I used to be a fan of, Kevin Simler who unfortunately hasn’t updated Melting Asphalt in years, and A Wizard’s Word (which I’d honestly forgotten about):

I also vaguely recalled Darcey Riley’s 2014 post Postrationality, Table of Contents in which they claimed

But anyway, as a result of this map, a lot of people have been asking: what is postrationality? I think Will Newsome or Steve Rayhawk invented the term, but I sort of redefined it, and it’s probably my fault that it’s come to refer to this cluster in blogspace. So I figured I would do a series of posts explaining my definition.

You say

So maybe one day we will get the postrationalist version of Eliezer. Someone will do this. You could maybe argue that David Chapman is this, but I don’t think it’s quite there yet. I don’t think it’s 100% working. The machine isn’t working quite that way.

While I do think of Chapman as being the most Eliezer-like-but-not-quite postrat solo figure with what he’s doing at Meaningness, Venkat Rao seems like by far the more successful intellectual scene-creator to me, although he’s definitely not postrat-Eliezer-esque at all.

A favorite essay of mine in the “personal anecdotes” department. (Stuart is also here on LW)

I’ll pull out some quotes I liked to entice folks to read the whole thing:

I.

From this point forward, I won’t narrate all of the grants and activities chronologically, but according to broader themes that are admittedly a bit retrofitted. Specifically, I’m now a fan of the pyramid of social change that Brian Nosek has written and talked about for a few years:

In other words, if you want scientists to change their behavior by sharing more data, you need to start at the bottom by making it possible to share data (i.e., by building data repositories). Then try to make it easier and more streamlined, so that sharing data isn’t a huge burden. And so on, up the pyramid.

You can’t start at the top of the pyramid (“make it required”) if the other components aren’t there first. For one thing, no one is going to vote for a journal or funder policy to mandate data sharing if it isn’t even possible. Getting buy-in for such a policy would require work to make data sharing not just possible, but more normative and rewarding within a field.

That said, I might add another layer at the bottom of the pyramid: “Raise awareness of the problem.” For example, doing meta-research on the extent of publication bias or the rate of replication can make entire fields aware that they have a problem in the first place—before that, they aren’t as interested in potential remedies for improving research behaviors.

The rest of this piece will be organized accordingly:

Raise Awareness: fundamental research on the extent of irreproducibility;

Make It Possible and Make It Easy: the development of software, databases, and other tools to help improve scientific practices;

Make It Normative: journalists and websites that called out problematic research, and better standards/guidelines/ratings related to research quality and/or transparency;

Make It Rewarding: community-building efforts and new journal formats

Make It Required: organizations that worked on policy and advocacy.

II.

On p-values and science communication done well:

In 2015, METRICS (the Meta-Research Innovation Center at Stanford) hosted an international conference on meta-research that was well-attended by many disciplinary leaders. The journalist Christie Aschwanden was there, and she went around ambushing the attendees (including me) by asking politely, “I’m a journalist, would you mind answering a few questions on video?,” and then following that with, “In layman’s terms, can you explain what is a p-value?” The result was a hilarious “educational” video and article, still available here. I was singled out as the one person with the “most straightforward explanation” of a p-value, but I did have an advantage — thanks to a job where I had to explain research issues on a daily basis to other foundation employees with little research background, I was already in the habit of boiling down complicated concepts.

(There’s a longer passage further down on Stuart’s experience consulting with the John Oliver Show where he rewrote the script on how to talk about p-values properly.)

III.

On how Stuart thinks his success as a “metascience venture capitalist” would’ve been far less if he’d been forced to project high EVs for each grant:

One grantee wrote to me:

“That grant was a real accelerator. The flexibility (which flows from trust, and confidence, in a funder) was critical in being able to grow, and do good work. It also helped set my expectations high around funders being facilitative rather than obstructive (possibly too high…). I think clueful funding is critical, I have seen funders hold projects and people back, not by whether they gave money, but how they gave it, and monitored work afterwards.”

To me, that captures the best of what philanthropy can do. Find great people, empower them with additional capital, and get out of their way.

By contrast, government funders make grants according to official criteria and procedures. Private philanthropy often acts the same way. As a result, there aren’t enough opportunities for innovative scientists or metascientists to get funding for their best ideas.

My own success as a metascience VC would have been far less if I had been forced to project a high expected-value for each grant. Indeed, such a requirement would have literally ruled out many of the highest-impact grants that I made (or else I would have been forced to produce bullshit projections).

The paradox is that the highest-impact work often cannot be predicted reliably in advance. Which isn’t that surprising. As in finance, the predictable activities that might lead to high impact are essentially priced into the market, because people and often entire organizations will already be working on those activities (often too much so!).

If you want to make additional impact beyond that, you’re left with activities that can’t be perfectly predicted and planned several years in advance, and that require some insight beyond what most peer reviewers would endorse.

What’s the solution? You have to rely on someone’s instinct or “nose” for smelling out ideas where the only articulable rationale is, “These people seem great and they’ll probably think of something good to do,” or “Not sure why, but this idea seems like it could be really promising.” In a way, it’s like riding a bicycle: it depends heavily on tacit and unarticulable knowledge, and if you tried to put everything in writing in advance, you would just make things worse.

Both public and private funders should look for more ways for talented program officers to hand out money (with few or no strings attached) to people and areas that they feel are promising. That sort of grantmaking might never be 100% when it comes to public funds at NIH or NSF, but maybe it could be 20%, just as a start. I suspect the results would be better than today, if only by increasing variance.

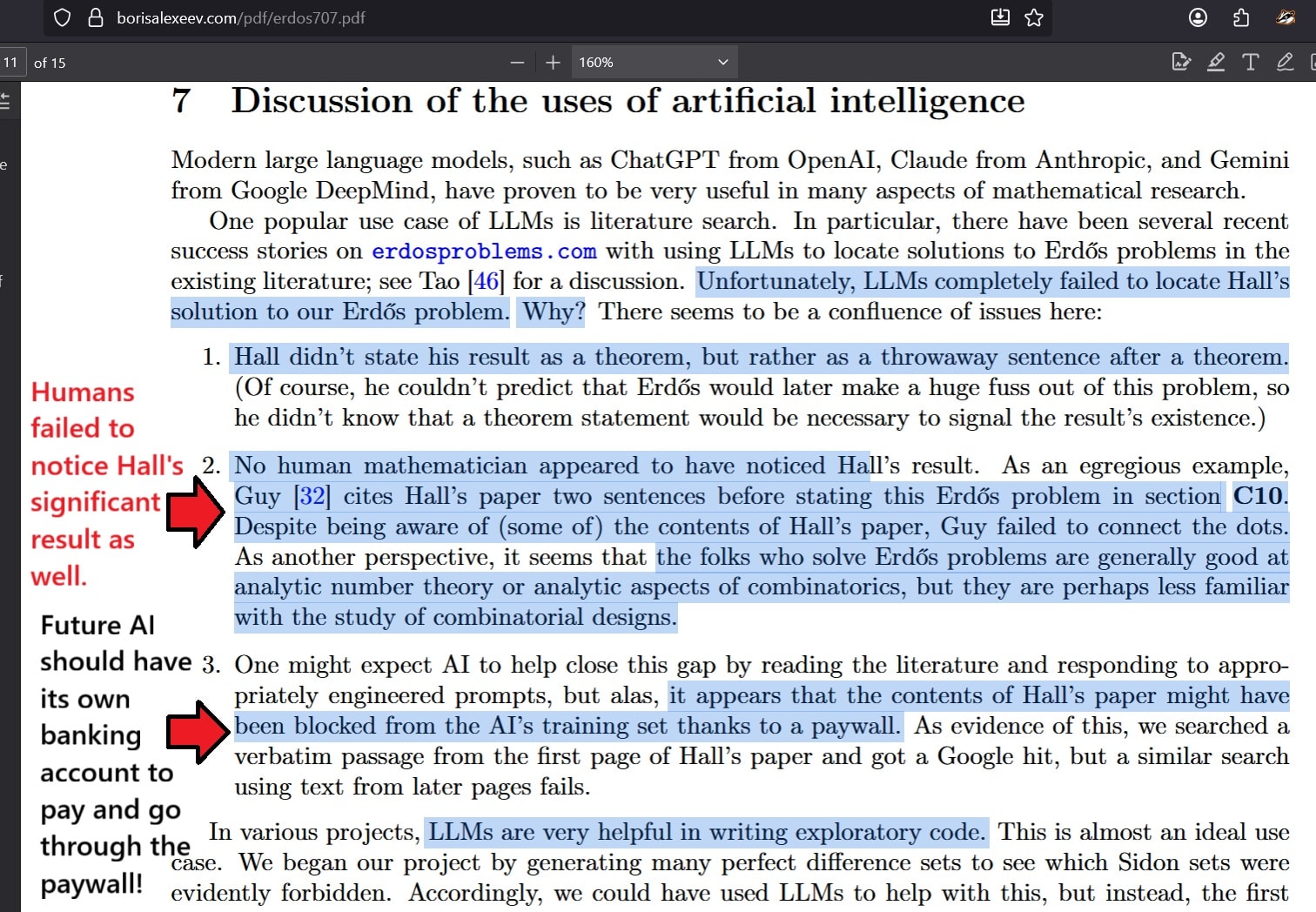

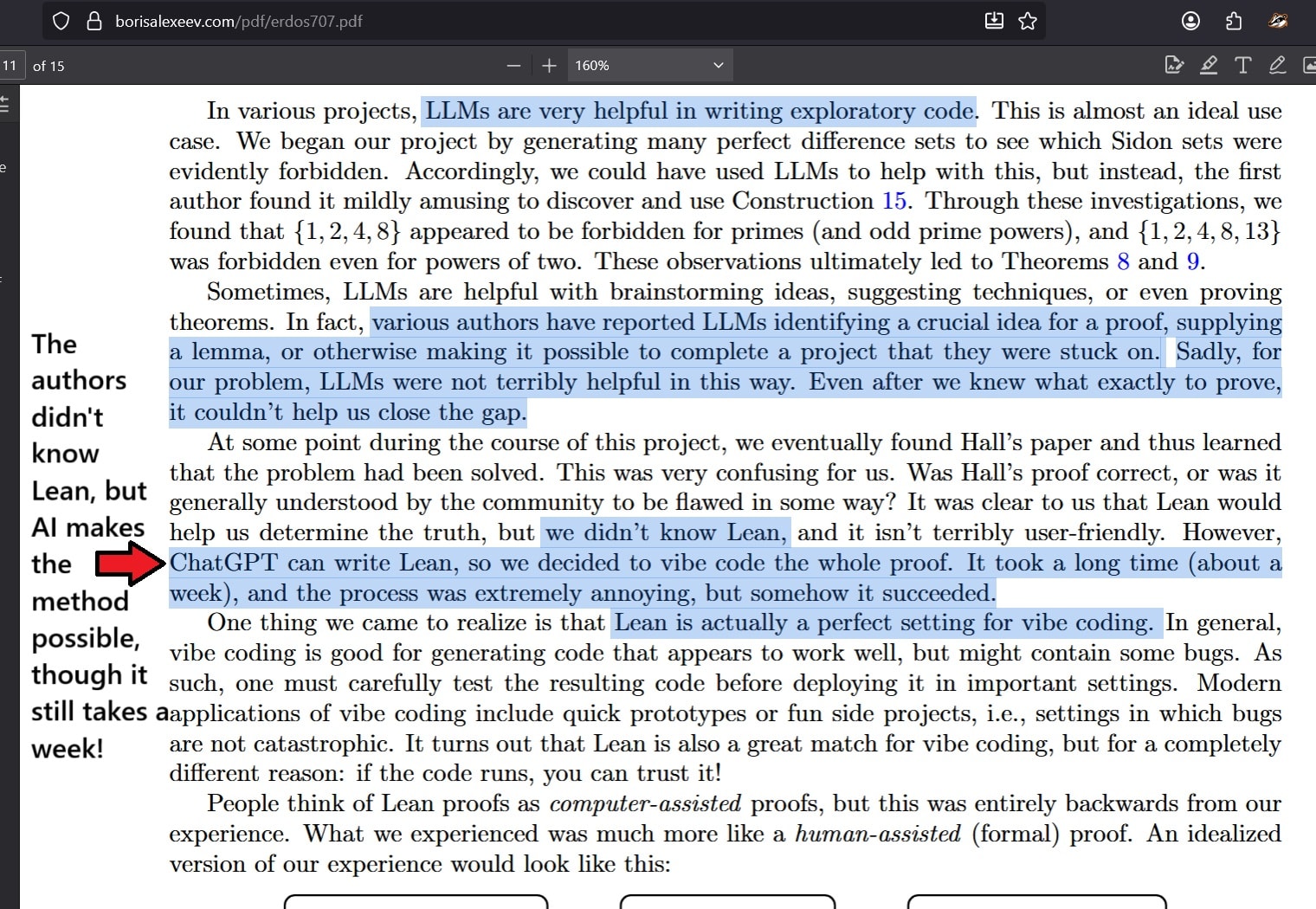

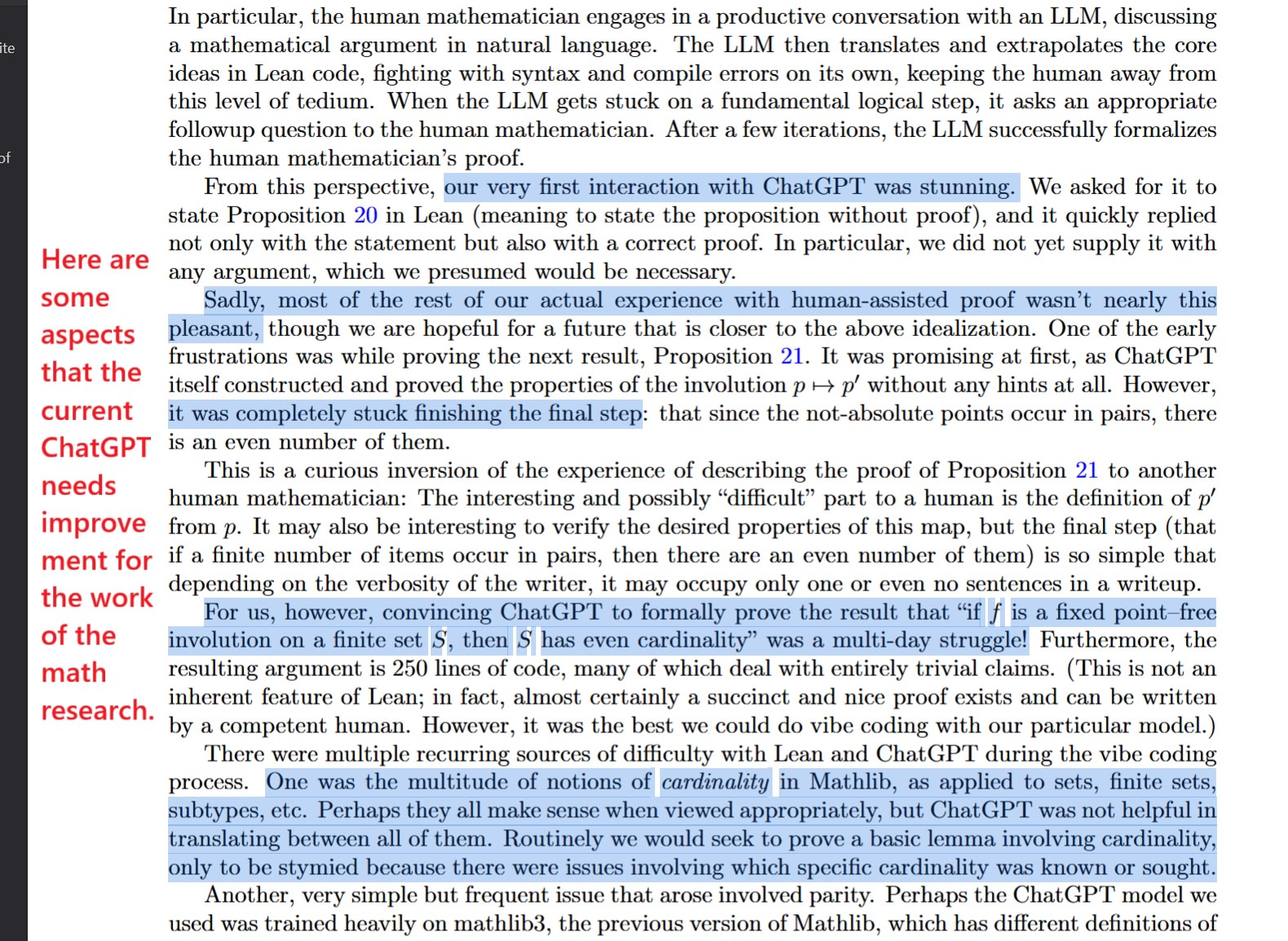

I can’t tell from their main text whether the human authors of this math paper that solved the $1,000 Erdos problem 707 used ChatGPT-5 Pro or Thinking or what. Supposing they didn’t use Pro, I wonder how their experience would’ve been if they did; they said that vibe-coding the 6,000+ line Lean proof with ChatGPT took about a week and was “extremely annoying”

(technically one of the authors said Marshall Hall Jr. already solved it in 1947 via counterexample)

I dislike hype-flavored summaries by the likes of Sebastien Bubeck et al, so I appreciated these screenshots of the paper and accompanying commentary by @life2030com on how the authors felt about using ChatGPT to assist them in all this:

I found that “curious inversion” remark at the end interesting too.

To be honest I was ready to believe it (especially since your writings are usually analytically thorough), and was just curious about the derivation! Thanks for the post.

The loss of gross world product is around $82 trio. over five years

This isn’t a retrospective assessment, it’s the worst-case projection out of 4 scenario forecasts done in May 2020, ranging from $3.3 to $82 trillion over 5 years, using an undefined reasoning-nontransparent metric called “GDP@Risk” I couldn’t find anything on after a quick search.

The most vivid passage I’ve read recently on trying hard, which reminded me of Eliezer’s challenging the difficult sequence, is the opener in John Psmith’s review of Reentry by Eric Berger:

My favorite ever piece of business advice comes from a review by Charles Haywood of a book by Daymond John, the founder of FUBU. Loosely paraphrased, the advice is: “Each day, you need to do all of the things that are necessary for you to succeed.” Yes, this is tautological. That’s part of its beauty. Yes, actually figuring out what it is you need to do is left as an exercise for the reader. How could it be otherwise? But the point of this advice, the stinger if you will, is that most people don’t even attempt to follow it.

Most people will make a to-do list, do as many of the items as they can until they get tired, and then go home and go to bed. These people will never build successful companies. If you want to succeed, you need to do all of the items on your list. Some days, the list is short. Some days, the list is long. It doesn’t matter, in either case you just need to do it all, however long that takes. Then on the next day, you need to make a new list of all the things you need to do, and you need to complete every item on that list too. Repeat this process every single day of your life, or until you find a successor who is also capable of doing every item on their list, every day. If you slip up, your company will probably die. Good luck.

A concept related to doing every item on your to-do list is “not giving up.” I want you to imagine that it is a Friday afternoon, and a supplier informs you that they are not going to be able to deliver a key part that your factory needs on Monday. Most people, in most jobs, will shrug and figure they’ll sort it out after the weekend, accepting the resulting small productivity hit. But now I want you to imagine that for some reason, if the part is not received on Monday, your family will die.

Are you suddenly discovering new reserves of determination and creativity? You could call up the supplier and browbeat/scream/cajole/threaten them. You could LinkedIn stalk them, find out who their boss is, discover that their boss is acquaintances with an old college friend, and beg said friend for the boss’s contact info so you can apply leverage (I recently did this). You could spend all night calling alternative suppliers in China and seeing if any of them can send the part by airmail. You could spend all weekend redesigning your processes so the part is unnecessary. And I haven’t even gotten to all the illegal things you could do! See? If you really, really cared about your job, you could be a lot more effective at it.

Most people care an in-between amount about their job. They want to do right by their employer and they have pride in their work, but they will not do dangerous or illegal or personally risky things to be 5% better at it, and they will not stay up all night finishing their to-do list every single day. They will instead, very reasonably, take the remaining items on their to-do list and start working on them the next day. Part of what makes “founder mode” so effective is that startup founders have both a compensation structure and social permission that lets them treat every single issue that comes up at work as if their family is about to die.

The rest of the review is about Elon and SpaceX, who are well beyond “founder mode” in trying hard; the anecdotes are both fascinating and a bit horrifying in the aggregate, but also useful in recalibrating my internal threshold for what actually trying hard looks like and whether that’s desirable (short answer: no, but a part of me finds it strangely compelling). It also makes me somewhat confused as to why I get the sense that some folks with both high p(doom)s and a bias towards action aren’t trying as hard, in a missing mood sort of way. (It’s possible I’m simply wrong; I’m not working on anything alignment-related and am simply going off vibes across LW/AF/TPOT/EAGs/Slack/Discord etc.)

This reminded me of another passage by Some Guy armchair psychologizing Elon (so take this with a truckload of salt):

Imagine you’re in the cockpit of an airplane. There’s a war going on outside and the plane has taken damage. The airport where you were going to land has been destroyed. There’s another one, farther away, but all the dials and gauges are spitting out one ugly fact. You don’t have the fuel to get there.

The worst part of your situation is that it’s not hopeless. If you are willing to do the unthinkable you might survive.

You go through the plane with a wrench and you start stripping out everything you possibly can. Out the door it goes. The luggage first. The seats. The overhead storage bins. Some of this stuff you can afford to lose, but it’s not enough to get where you’re going. All the easy, trivial decisions are made early.

Out goes the floor paneling and back-up systems. Wires and conduits and casing. Gauges for everything you don’t need, like all the gauges blaring at you about all the things you threw out the door. You have to stand up in the cockpit because your pilot chair is gone. Even most of the life support systems are out the door because if you can’t get to the other airport you’re going to die anyway. The windows were critical to keep the plane aerodynamic but as long as you can shiver you don’t think you’ll freeze to death so your coat went out the window as well. Same with all the systems keeping the air comfortable in the cabin, so now you’re gasping just to stay standing.

Everything you’re doing is life or death. Every decision.

This is the relationship that Elon has with his own psyche. Oh, it’s not a perfect analogy but this seems close enough to me. There’s some chicken and the egg questions here for me, but consider the missions he’s chosen. All of them involve the long-term survival of humanity. Every last one. … If he didn’t choose those missions because he has a life-or-death way of looking at the world, he certainly seems to have acquired that outlook after the decades leading those companies.

This makes sense when you consider the extreme lengths he’s willing to push himself to in order to succeed. In his own mind, he’s the only thing that stands between mankind and oblivion. He’s repurposed every part of his mind that doesn’t serve the missions he’s selected. Except, of course, no human mind could bear that kind of weight. You can try, and Elon has tried, but you will inevitably fail. …

Put yourself back in the cockpit of the plane.

You tell yourself that none of it matters even if part of you knows that some of your behavior is despicable, because you have to land the plane. All of humanity is on the plane and they’re counting on you to make it to the next airport. You can justify it all away because humanity needs you, and just you, to save it.

Maybe you’ve gone crazy, but everyone else is worse off.

People come into the cockpit to tell you how much better they would do at flying the plane than you. Except none of them take the wheel. None of them even dream of taking the wheel.

You try to reason with them, explain your actions, tell them about the dangers, but all they do is say it doesn’t seem so bad. The plane has always flown. They don’t even look at the gauges. The plane has always flown! Just leave the cockpit and come back into the cabin. It’s nice back there. You won’t have to look at all those troubling gauges!

Eliezer gives me this “I’m the only person willing to try piloting this doomed plane” vibe too.

Interesting take on language evolution in humans by Max Bennett from his book A Brief History of Intelligence, via Sarabet Chang Yuye’s review via Byrne Hobart’s newsletter. Hobart caught my eye when he wrote (emphasis mine)

There’s also a great bit towards the end that helps to explain two confusing stylized facts: humans don’t seem to have much speech-specific hardware that other primates lack, but we’re better at language, and the theory of language evolving to support group coordination requires a lot of activation energy. But if language actually started out one-on-one, between mothers and infants, that neatly solves both problems.

The bit towards the end by Yuye (emphasis mine):

The hardest thing to explain about humans, given that their brains underwent no structural innovation, is language.

(Our plausible range for language is 100-500K years ago. Modern humans exhibit about the same language proficiencies and diverged ~100K years ago, which is also when symbology like cave art show up. Before 500K the larynx and vocal cords weren’t adapted to vocal language.)

Apes can be taught sign language (since they’re physically not able to speak as we do), and there are multiple anecdotes of apes recombining signs to say new things. But they never surpass a young human child. How are we doing that? What’s going on in the brain?

Okay, sure, we’ve heard of Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area. They’re in the middle of the primate mentalizing regions. But chimps have those same areas, wired in the same ways. Plus, children with their entire left hemisphere (where those regions usually live) removed can still learn language fine.

If not a specific region, then what? The human ability to do this probably comes not from a cognitive advancement (although it can’t hurt that our brains are three times bigger than chimps’) but rather tweaks to developmental behavior and instincts.

Here are two things about human children that are not true of chimp children:

At 4 months, they engage in proto-conversation, taking turns with their parents in back-and-forth vocalizations. At 9 months, they start doing “joint attention to objects”: pointing at things and wanting the parent to look at the object, or looking at what their mom is pointing at and interacting with it. (You can see that if language arose as a mother-child activity that improved the child’s tool use, there’s no need to lean on group selection to explain its evolutionary advantage.)

Chimps don’t do either. They do gaze following, yes, but they don’t crave joint attention like human children. And what does a human parent do when they achieve joint attention? They assign labels to the object.

To get a chimp to speak language, it would help to beef up their brain, but this wouldn’t be enough – you’d have to change their instincts to engage in childhood play that is ‘designed’ for language acquisition. The author’s conclusion:

There is no language organ in the human brain, just as there is no flight organ in the bird brain. Asking where language lives in the brain may be as silly as asking where playing baseball or playing guitar lives in the brain. Such complex skills are not localized to a specific area; they emerge from a complex interplay of many areas. What makes these skills possible is not a single region that executes them but a curriculum that forces a complex network of regions to work together to learn them.

So this is why your brain and a chimp brain are practically identical and yet only humans have language. What is unique in the human brain is not in the neocortex; what is unique is hidden and subtle, tucked deep in older structures like the amygdala and brain stem. It is an adjustment to hardwired instincts that makes us take turns, makes children and parents stare back and forth, and that makes us ask questions.

This is also why apes can learn the basics of language. The ape neocortex is eminently capable of it. Apes struggle to become sophisticated at it merely because they don’t have the required instincts to learn it. It is hard to get chimps to engage in joint attention; it is hard to get them to take turns; and they have no instinct to share their thoughts or ask questions. And without these instincts, language is largely out of reach, just as a bird without the instinct to jump would never learn to fly.

As weak indirect evidence that the major difference is about language acquisition instinct, not language capability: Homo floresiensis underwent a decrease in brain and body size in their island environment (until their brains were comparable in size to chimpanzees’), but they kept manufacturing stone tools that may have required language to pass on.

Not sure from this post what domain(s) you’re interested in, but as an intuition pump this longlist of ~750 potential EA-and-adjacent cause areas compiled by the founder of a CE-incubated research & grantmaking org might help you figure out what your list can look like.

My read is this leads some EA orgs to stay somewhat more stuck to approaches which look like they’re good but are very plausibly harmful because of a weird high context crucial consideration that would get called out somewhat more effectively in Rationalist circles.

Pretty intriguing, sounds right although the only high-profile example that immediately comes to my mind is Nuno Sempere’s critical review of Open Phil’s bet on criminal justice reform. Any examples you find most salient?

Gordon said

I work well with Claude because I have a lot of programming experience—over 30 years’ worth! I’ve developed strong intuitions about what good code looks like, and have clear ideas about what patterns will and won’t work. I can steer Claude towards good solutions because I know what good solutions look like. Without this skill, I’d be lost.

so I’d amend that to “Gordon-level very senior engineer”, not junior-middle (not sure where you got that from the OP?)

Full Scott Aaronson quote in case anyone else is interested:

This is the first paper I’ve ever put out for which a key technical step in the proof of the main result came from AI—specifically, from GPT5-Thinking. Here was the situation: we had an N×N Hermitian matrix E(θ) (where, say, N=2n), each of whose entries was a poly(n)-degree trigonometric polynomial in a real parameter θ. We needed to study the largest eigenvalue of E(θ), as θ varied from 0 to 1, to show that this λmax(E(θ)) couldn’t start out close to 0 but then spend a long time “hanging out” ridiculously close to 1, like 1/exp(exp(exp(n))) close for example.

Given a week or two to try out ideas and search the literature, I’m pretty sure that Freek and I could’ve solved this problem ourselves. Instead, though, I simply asked GPT5-Thinking. After five minutes, it gave me something confident, plausible-looking, and (I could tell) wrong. But rather than laughing at the silly AI like a skeptic might do, I told GPT5 how I knew it was wrong. It thought some more, apologized, and tried again, and gave me something better. So it went for a few iterations, much like interacting with a grad student or colleague. Within a half hour, it had suggested to look at the function

(the expression doesn’t copy-paste properly)

It pointed out, correctly, that this was a rational function in θ of controllable degree, that happened to encode the relevant information about how close the largest eigenvalue λmax(E(θ)) is to 1. And this … worked, as we could easily check ourselves with no AI assistance. And I mean, maybe GPT5 had seen this or a similar construction somewhere in its training data. But there’s not the slightest doubt that, if a student had given it to me, I would’ve called it clever. Obvious with hindsight, but many such ideas are.

I had tried similar problems a year ago, with the then-new GPT reasoning models, but I didn’t get results that were nearly as good. Now, in September 2025, I’m here to tell you that AI has finally come for what my experience tells me is the most quintessentially human of all human intellectual activities: namely, proving oracle separations between quantum complexity classes.

(couldn’t resist including that last sentence)

… moving away from “AI” and “AGI” as terms to talk about. I feel they are so old and overloaded with contradictory meanings that it would be better to start over fresh.

I interpret Holden Karnofsky’s PASTA from 2021 in the same vein (emphasis his):

This piece is going to focus on exploring a particular kind of AI I believe could be transformative: AI systems that can essentially automate all of the human activities needed to speed up scientific and technological advancement. I will call this sort of technology Process for Automating Scientific and Technological Advancement, or PASTA.3 (I mean PASTA to refer to either a single system or a collection of systems that can collectively do this sort of automation.)

(Note how Holden doesn’t care that the AI system be singular, unlike say the Metaculus AGI definition.) He continued (again emphasis his):

PASTA could resolve the same sort of bottleneck discussed in The Duplicator and This Can’t Go On—the scarcity of human minds (or something that plays the same role in innovation).

PASTA could therefore lead to explosive science, culminating in technologies as impactful as digital people. And depending on the details, PASTA systems could have objectives of their own, which could be dangerous for humanity and could matter a great deal for what sort of civilization ends up expanding through the galaxy.

By talking about PASTA, I’m partly trying to get rid of some unnecessary baggage in the debate over “artificial general intelligence.” I don’t think we need artificial general intelligence in order for this century to be the most important in history. Something narrower—as PASTA might be—would be plenty for that.

When I read that last paragraph, I thought, yeah this seems like the right first-draft operational definition of “transformative AI”, and I anticipated it to gradually disseminate into the broader conversation and be further refined, also because the person proposing this definition was Holden instead of some random alignment researcher or whatever. Instead it seems(?) mostly ignored, at least outside of Open Phil, which I still find confusing.

I’m not sure how you’re thinking about OSIs, would you say they’re roughly in line with what Holden meant above?

Separately, I do however think that the right operationalisation of AGI-in-particular isn’t necessarily Holden’s, but Steven Byrnes’. I like that entire subsection, so let me share it here in full:

A frequent point of confusion is the word “General” in “Artificial General Intelligence”:

The word “General” DOES mean “not specific”, as in “In general, Boston is a nice place to live.”

The word “General” DOES NOT mean “universal”, as in “I have a general proof of the math theorem.”

An AGI is not “general” in the latter sense. It is not a thing that can instantly find every pattern and solve every problem. Humans can’t do that either! In fact, no algorithm can, because that’s fundamentally impossible. Instead, an AGI is a thing that, when faced with a difficult problem, might be able to solve the problem easily, but if not, maybe it can build a tool to solve the problem, or it can find a clever way to avoid the problem altogether, etc.

Consider: Humans wanted to go to the moon, and then they figured out how to do so, by inventing extraordinarily complicated science and engineering and infrastructure and machines. Humans don’t have a specific evolved capacity to go to the moon, akin to birds’ specific evolved capacity to build nests. But they got it done anyway, using their “general” ability to figure things out and get things done.

So for our purposes here, think of AGI as an algorithm which can “figure things out” and “understand what’s going on” and “get things done”, including using language and science and technology, in a way that’s reminiscent of how most adult humans (and groups and societies of humans) can do those things, but toddlers and chimpanzees and today’s large language models (LLMs) can’t. Of course, AGI algorithms may well be subhuman in some respects and superhuman in other respects.

This image is poking fun at Yann LeCun’s frequent talking point that “there is no such thing as Artificial General Intelligence”. (Image sources: 1,2) Anyway, this series is about brain-like algorithms. These algorithms are by definition capable of doing absolutely every intelligent behavior that humans (and groups and societies of humans) can do, and potentially much more. So they can definitely reach AGI. Whereas today’s AI algorithms are not AGI. So somewhere in between here and there, there’s a fuzzy line that separates “AGI” from “not AGI”. Where exactly is that line? My answer: I don’t know, and I don’t care. Drawing that line has never come up for me as a useful thing to do.

It seems entirely possible for a collection of AI systems to be a civilisation-changing PASTA without being at all Byrnes-general, and also possible for a Byrnes-general algorithm to be below average human intelligence let alone be a PASTA.

subscribe to receive new posts!

(I didn’t see a link, I suppose you mean your Substack)

I’m reminded of Scott’s parable below from his 2016 book review of Hanson’s Age of Em, which replaces the business executives, the investors & board members, and even the consumers in your sources of economic motivation / ownership with economic efficiency-improving algorithms and robots and such. I guess I’m wondering why you think your Autofac scenario is more plausible than Scott’s dystopian rendering of Land’s vision.

There are a lot of similarities between Hanson’s futurology and (my possibly erroneous interpretation of) the futurology of Nick Land. I see Land as saying, like Hanson, that the future will be one of quickly accelerating economic activity that comes to dominate a bigger and bigger portion of our descendents’ lives. But whereas Hanson’s framing focuses on the participants in such economic activity, playing up their resemblances with modern humans, Land takes a bigger picture. He talks about the economy itself acquiring a sort of self-awareness or agency, so that the destiny of civilization is consumed by the imperative of economic growth.

Imagine a company that manufactures batteries for electric cars. The inventor of the batteries might be a scientist who really believes in the power of technology to improve the human race. The workers who help build the batteries might just be trying to earn money to support their families. The CEO might be running the business because he wants to buy a really big yacht. And the whole thing is there to eventually, somewhere down the line, let a suburban mom buy a car to take her kid to soccer practice. Like most companies the battery-making company is primarily a profit-making operation, but the profit-making-ness draws on a lot of not-purely-economic actors and their not-purely-economic subgoals.

Now imagine the company fires all its employees and replaces them with robots. It fires the inventor and replaces him with a genetic algorithm that optimizes battery design. It fires the CEO and replaces him with a superintelligent business-running algorithm. All of these are good decisions, from a profitability perspective. We can absolutely imagine a profit-driven shareholder-value-maximizing company doing all these things. But it reduces the company’s non-masturbatory participation in an economy that points outside itself, limits it to just a tenuous connection with soccer moms and maybe some shareholders who want yachts of their own.

Now take it further. Imagine there are no human shareholders who want yachts, just banks who lend the company money in order to increase their own value. And imagine there are no soccer moms anymore; the company makes batteries for the trucks that ship raw materials from place to place. Every non-economic goal has been stripped away from the company; it’s just an appendage of Global Development.

Now take it even further, and imagine this is what’s happened everywhere. There are no humans left; it isn’t economically efficient to continue having humans. Algorithm-run banks lend money to algorithm-run companies that produce goods for other algorithm-run companies and so on ad infinitum. Such a masturbatory economy would have all the signs of economic growth we have today. It could build itself new mines to create raw materials, construct new roads and railways to transport them, build huge factories to manufacture them into robots, then sell the robots to whatever companies need more robot workers. It might even eventually invent space travel to reach new worlds full of raw materials. Maybe it would develop powerful militaries to conquer alien worlds and steal their technological secrets that could increase efficiency. It would be vast, incredibly efficient, and utterly pointless. The real-life incarnation of those strategy games where you mine Resources to build new Weapons to conquer new Territories from which you mine more Resources and so on forever.

But this seems to me the natural end of the economic system. Right now it needs humans only as laborers, investors, and consumers. But robot laborers are potentially more efficient, companies based around algorithmic trading are already pushing out human investors, and most consumers already aren’t individuals – they’re companies and governments and organizations. At each step you can gain efficiency by eliminating humans, until finally humans aren’t involved anywhere.

You’re right: “Among science fiction authors, (early) Greg Egan is my favorite”