Lessons I’ve Learned from Self-Teaching

In 2018, I was a bright-eyed grad student who was freaking out about AI alignment. I guess I’m still a bright-eyed grad student freaking out about AI alignment, but that’s beside the point.

I wanted to help, and so I started levelling up. While I’d read Nate Soares’s self-teaching posts, there were a few key lessons I’d either failed to internalize or failed to consider at all. I think that implementing these might have doubled the benefit I drew from my studies.

I can’t usefully write a letter to my past self, so let me write a letter to you instead, keeping in mind that good advice for past-me may not be good advice for you.

Make Sure You Remember The Content

TL;DR: use a spaced repetition system like Anki. Put in cards for key concepts and practice using the concepts. Review the cards every day without fail. This is the most important piece of advice.

The first few months of 2018 were a dream: I was learning math, having fun, and remaking myself. I read and reviewed about one textbook a month. I was learning how to math, how to write proofs and read equations fluently and think rigorously.

I had so much fun that I hurt my wrists typing up my thoughts on impact measures. This turned a lot of my life upside-down. My wrists wouldn’t fully heal for two years, and a lot happened during that time. After I hurt my wrists, I became somewhat depressed, posted less frequently, and read fewer books.

When I looked back in 2019/2020 and asked “when and why did my love for textbooks sputter out?”, the obvious answer was “when I hurt my hands and lost my sense of autonomy and became depressed, perchance? And maybe I just became averse to reading that way?”

The obvious answer was wrong, but its obvious-ness stopped me from finding the truth until late last year. It felt right, but my introspection had failed me.

The real answer is: when I started learning math, I gained a lot of implicit knowledge, like how to write proofs and read math (relatively) quickly. However, I’m no Hermione Granger: left unaided, I’m bad at remembering explicit facts / theorem statements / etc.

I gained implicit knowledge but I didn’t remember the actual definitions, unless I actually used them regularly (e.g. as I did for real analysis, which I remained quite fluent in and which I regularly use in my research). Furthermore, I think I coincidentally hit steeply diminishing returns on the implicit knowledge around when I injured myself.

So basically I’m reading these math textbooks, doing the problems, getting a bit better at writing proofs but not really durably remembering 95% of the content. Maybe part of my subconscious noticed that I seem to be wasting time, that when I come back four months after reading a third of a graph theory textbook, I barely remember the new content I had “learned.” I thought I was doing things right. I was doing dozens of exercises and thinking deeply about why each definition was the way it was, thinking about how I could apply these theorems to better reason about my own life and my own research, etc.

I explicitly noticed this problem in late 2020 and thought,

is there any way I know of to better retain content?

… gee, what about that thing I did in college that let me learn how to read 2,136 standard-use Japanese characters in 90 days? you know, Anki spaced repetition, that thing I never tried for math because once I tried and failed to memorize dozens of lines of MergeSort pseudocode with it?

hm…

This was the moment I started feeling extremely silly (the exact thought was “there’s no possible way that my hand is big enough for how facepalm this moment is”, IIRC), but also extremely excited. I could fix my problem!

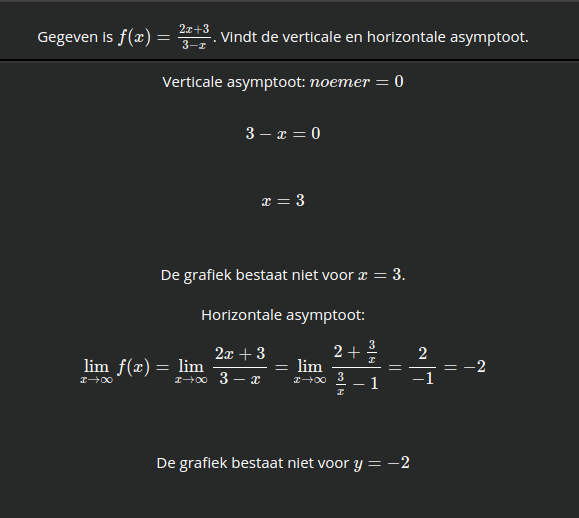

And a problem this was. In early 2020, I had an interview where I was asked to compute . I was stumped, even though this was simple high school calculus (just integrate by parts!). I failed the interview and then went back to learning algebraic topology and functional analysis and representation theory. You know, nothing difficult like high school calculus.

I was pretty frustrated with myself.

It’s not that I didn’t understand it. I just didn’t remember it, especially on the spot. The worst part was that I had brushed up on calculus the previous spring, and I still didn’t remember it. Turns out that my brain won’t remember material it doesn’t use for months on end, even if forgetting that material would be embarrassing.

Enter Anki, an amazing spaced repetition system ($20 for iOS, free for computer). The way I like to explain Anki is:

Anki is a flashcard application into which you can enter a constant number of cards each day while retaining a constant average daily workload. You can add cards each day, without having to study longer and longer to get through all of the cards.

I currently think that unless you have really good memory or you’re not learning content you want to remember months from now, you’re making a mistake by not using a spaced repetition system. Read Gwern for more on spaced repetition.

Spaced repetition seems especially useful for students. In college, I ran an experiment: for an upper-level French class, I put things I didn’t know how to say into Anki, reviewed daily, and otherwise didn’t study at all. I got an A.

How powerful might a bright 6th grader grow, were they to use Anki every day for their whole life? The best time to plant a tree may have been in sixth grade, and the second-best time may have been in seventh grade, but you should still plant the tree now rather than never.

(Once completed, the reviews in the next few days will be pushed into some of the future days, so this projection is slightly optimistic, but you get the point.)

I love Anki, and I was foolish to circumscribe it to language-learning. I now use Anki to remember key concepts from academic talks, LessWrong blogposts, and yes—textbooks. Which I now love again, and which I read for ~an hour daily again, because I’m actually retaining the content.

Measure theory, ring theory, random stuff about taxonomy and epidemiology, quantum mechanics, basic physics, deep RL papers, they all go into Anki, and Anki cards go into my brain—and stay there!

What a wonderful time to be alive.

Random Anki tips

I know quite a bit about how to best use Anki, so if you try this and it doesn’t seem to work, please message me instead of banging your head against the wall or giving up!

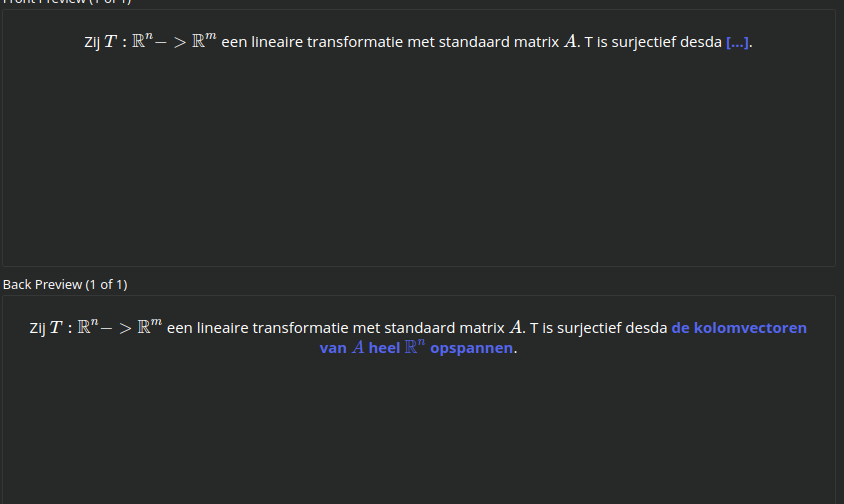

Use cloze deletions on short cards. Cloze deletions hide a small part of the text, and make you remember it given the rest of the content. They are fast to make and fast to review.

The vast, vast majority of my cards are cloze now, and they weren’t when I first wrote this post. I think that was a mistake.

Study every day, preferably at the same time so you aren’t always scrambling to get it done before bedtime.

Sync with AnkiWeb so you don’t lose all your cards if your device dies.

Save time by just screenshotting theorem statements and/or proofs.

EDIT: micpie recommends the Mathpix OCR software, which clips text into MathJax code. This works really well, in my experience.

Image occlusion is a great add-on.

On iPad, I like using MarginNote to read. I can just draw rectangles around key parts of the pdf, make cloze deletions in the app, and then export the cards to an Anki deck.

Don’t just memorize proofs, focus on the key ideas. Don’t just memorize definitions, throw in several example problems which are small enough to actually do in your head (or with a scrap of paper).

For example, if I’m trying to really ingrain the concept of an efficient pseudorandom number generator, I have cards where I reason about it by completing short proofs:

Am I ever going to actually use this math for my research? Probably not. Doesn’t matter. Anki makes it cheap to learn and retain things.

If you get a card wrong more than 4 times in the first week, it’s a bad card. Remake it.

Use MathJax instead of Latex, because MathJax renders instantly.

My trigger for “I should add a new card” is reading something and thinking, “this is a cool concept!”

I recommend adding cards liberally. Don’t worry about getting the formatting or phrasing perfect at first. Just add cards and you’ll develop a taste for what should be added, and how.

Read Several Textbooks Concurrently

TL;DR study several topics at once so that your brain has time to cement the concepts you’re learning, before the text builds on those concepts further.

AllAmericanBreakfast’s recent post is great, so I’ll refer you to that to make this point:

Wait, what? You want me to make life easier on myself by, instead of studying calculus...studying calculus, linear algebra, and statistics all at once?

~ AllAmericanBreakfast, The Multi-Tower Study Strategy

The basic idea is that your brain needs time to really cement a new idea in, and so you should study several topics at once in dependency-heavy areas like mathematics. This advice matches up with both my recent personal experience and with advice I received early on from Qiaochu Yuan, but which I had unfortunately ignored.

For example, right now I’m reading Nielsen and Chuang’s Quantum Computation and Quantum Information, Evan Chen’s The Infinite Napkin, and a ridiculously easy physics book, Kuhn and Noschese’s A Self-Teaching Guide: Basic Physics (more on this later). Previously, I’d been going back through Wasserman’s All of Statistics and Pearl’s Causality after reading Pearl’s Book of Why.

I always feel like I’m learning something new instead of banging my head against the wall. Sometimes you should just read one book, but if you don’t need to cram, I recommend diversifying.

Completing The Whole Textbook Is Usually a Big Waste of Time, Please Don’t Do It

TL;DR extract the most useful / central concepts and remember them forever via Anki. This doesn’t require grasping every arcanum, every detail of a textbook.

When I started reading textbooks, I completed the whole book. I didn’t want to miss a crucial concept. But the thing about crucial concepts is that they pop up everywhere. If you missed a crucial concept, you’ll know. You’re not going to wake up 20 years from now and be like, “OH NO! I forgot to learn about ‘force’ when I self-studied physics! And I forgot to learn about injectivity in linear algebra!”

As you read more, you’ll get a taste for what’s probably important, and what’s details you can reference later if need be. You can also ask experts if you should study part of a book—this is one key benefit of having an actual teacher.

But don’t complete the whole book and all of its exercises, if you just want to become a polymath. Leverage the Pareto principle, get 80% of the benefit out of the key 20/30/40% of the concepts and exercises, and then move on.

Another reason I used to do this a lot was that I wanted to look good by being able to mention on e.g. my resume that I had read the whole book. It’s a lot more impressive to say “I read these 10 textbooks” than “I read large parts of this book, and some of this book, and a little of this one, and a lot of this other book.” I’ve found that learning well requires keeping an eye out for these instincts. My brain is not my friend in this battle.

I now often ask myself “am I doing this, at least in part, in order to look good?”. Sometimes I answer ‘yes’, and sometimes I do it anyways—wanting to look good isn’t always bad. But there are sometimes things more important than looking good.

Read Easier Textbooks Instead of Struggling Valiantly

TL;DR even though slogging through tough textbooks makes you feel sophisticated and smart, don’t.

Imagine I’m learning how to program, but I’ve never used a computer before. Learning to program while learning to operate a computer, will probably take longer than learning to operate a computer and then learning to program. Learning time is superadditive in terms of your ignorance / the dependencies you’re missing.

But it’s worse than that. Imagine I’m learning quantum mechanics, but I don’t know any linear algebra either. I’m now trying to do three things:

Learn linear algebra,

Learn the formal postulates of quantum mechanics, and

Tie all of this into the real world.

Similarly, if I’m trying to learn fluid mechanics without knowing how to manipulate partial differential equations (PDEs), it might look trying to simultaneously

Learn PDEs,

Learn the physical equations, such as Navier-Stokes, and

Tie all of this into the real world to explain what I already know about e.g. water and rivers and blood pressure.

But what if instead I picked up some dumb book that doesn’t even have any calculus, and let it give me approximate explanations via e.g. Archimedes’ principle:

Archimedes’ principle states that the upward buoyant force that is exerted on a body immersed in a fluid, whether fully or partially, is equal to the weight of the fluid that the body displaces. (Wikipedia)

I breeze through this book no problem, and I can see how to tie in these laws to explain my intuitive models: “logs float more easily than rocks because rock is denser than wood, and so the buoyant force from Archimedes’ principle is enough to support the weight of a log.” So I’m taking care of point #3, “tie this content into the real world.”

Then, suppose I learn about PDEs and become comfortable with them. Now all I need to do to learn a piece of fluid mechanics is to learn the relevant physical equation, and then think about how it implies things like Archimedes’ principle. Crucially, via this method, I’m only confused about one thing at a time. Build models in the right order!

Be Comfortable with Approximate Models

TL;DR allow yourself to learn things in order of comprehensibility: don’t try to learn general relativity before Newton’s law of gravitation.

In 2019, I wanted to learn a bit of chemistry. I got my hands on a high school chemistry textbook. I got stuck on chapter two because I was being too strict about forming gears-level models.

I was stuck because I was thinking about electron shells. The book acknowledged the Bohr model of the atom was wrong, electrons aren’t really discrete particles orbiting the nucleus:

But I got nerd-sniped into trying to understand how the electron standing wave only has solutions for certain energy levels, which is a result of quantum mechanics (or so I remember reading). I couldn’t understand why, and so the knowledge felt “fake.”

It wasn’t like I explicitly reasoned “this model is wrong and so I’m not going to keep reading this book”, it felt more like… I just wasn’t that hungry to learn this, because it wasn’t “real.” And I gradually stopped returning to that book.

Learn things quickly, note your confusions, and correct them later when the Anki cards show up again. Let yourself learn approximate models of reality.

Conclusion

I knew about the “read easier textbooks” advice already, but I didn’t apply it. Perhaps I just didn’t recognize a chance to apply it. The same forces of chaos and entropy and madness which prevented my applying e.g. Luke Muelhauser’s advice, may prevent you from applying this post’s advice. If you think any of this advice might help you, I recommend setting up a plan now for how and when you’ll implement it.

- Insights from Modern Principles of Economics by (22 Sep 2021 5:19 UTC; 81 points)

- Voting Results for the 2021 Review by (1 Feb 2023 8:02 UTC; 66 points)

- Don’t be afraid of the thousand-year-old vampire by (18 Apr 2022 1:22 UTC; 38 points)

- Define Your Learning Goal: Competence Or Broad Knowledge by (25 Jan 2021 20:47 UTC; 37 points)

- How I use Anki: expanding the scope of SRS by (12 Apr 2022 8:28 UTC; 37 points)

- How I Learn From Textbooks by (12 Feb 2023 4:45 UTC; 26 points)

- A Gentle Introduction on How to Use Anki to Improve Your Memory by (4 Feb 2021 9:59 UTC; 19 points)

- Spaced Repetition Systems for Intuitions? by (28 Jan 2021 17:23 UTC; 19 points)

- How I use Anki: expanding the scope of SRS by (EA Forum; 12 Apr 2022 8:40 UTC; 17 points)

- 's comment on An Opinionated Guide to Using Anki Correctly by (13 Jul 2025 19:05 UTC; 8 points)

- 's comment on AMA: Ask Career Advisors Anything by (EA Forum; 21 Jul 2025 17:38 UTC; 4 points)

- 's comment on Judgment Day: Insights from ‘Judgment in Managerial Decision Making’ by (24 Jan 2021 19:51 UTC; 4 points)

- 's comment on Feedback for learning by (2 Feb 2021 22:15 UTC; 3 points)

- 's comment on papetoast’s Shortforms by (9 Jan 2023 10:17 UTC; 1 point)

This post is a solid list of advice on self-studying. It matches the Review criterion of posts that continue to affect my behavior. (I don’t explicitly think back to the post, but I do occasionally bring up its advice in my mind, like “as yes, it’s actually good to read multiple textbooks concurrently and not necessarily finish them”.)

I actually disagree with the “most important piece of advice”, which is to use spaced repetition software. Multiple times in my life, I have attempted to incorporate an SRS habit into my life, reflecting on why it previously failed, and attempting to account for that failure mechanism. But through it all it, I have not gotten it to work for me. Of course, YMMV, and I am excited for people to continue trying to take advantage of the concept of spaced repetition.

But I solidly endorse the other four major pieces of advice in this post.

I’m glad I started using Anki. I did Anki 362⁄365 days this year.

I averaged 19 minutes of review a day (although I really think review tended to take longer), which nominally means I spent 4.75 clock-days studying Anki.

Seems very worth it, in my experience.

Oh yeah, I track my time with toggl and use anki. Anki’s time numbers are always undercounting my own measurements.

I think this is because anki is only counting how long you spend looking at the front of the card. Time spent looking at the back of a card is presumably after you’ve already answerd the question, and so doesn’t count.