How To Dress To Improve Your Epistemics

When it comes to epistemics, there is an easy but mediocre baseline: defer to the people around you or the people with some nominal credentials. Go full conformist, and just agree with the majority or the experts on everything. The moon landing was definitely not faked, washing hands is important to stop the spread of covid, whatever was on the front page of the New York Times today was basically true, and that recent study finding that hydroxyhypotheticol increases asthma risk among hispanic males in Indianapolis will definitely replicate.

Alas, memetic pressures and credential issuance and incentives are not particularly well aligned with truth or discovery, so this strategy fails predictably in a whole slew of places.

Among those who strive for better than baseline epistemics, nonconformity is a strict requirement. Every single place where you are right and the majority of people are wrong must be a place where you disagree with the majority of people. Every single place where you are right and so-called “experts” are wrong is a place where you disagree with the “experts”.

And standard wisdom is that visibly disagreeing with the mainstream costs social weirdness points. Say that one story in the Times is basically wrong, and people might listen. Say that most stories in the Times are basically wrong, and people start to think you’re a conspiracy theorist. Spend too many weirdness points, diverge from “normal” in too many ways, and your social status sinks.

And most humans feel really, really awful when their social status sinks. Which means they feel pressure not to spend too many weirdness points, and thus pressure to not disagree too much with the perceived majority or experts.

But there’s a great big giant underutilized loophole: coolness.

Coolness = Status Countersignalling

Coolness is simultaneously high status and inherently opposed to mainstream conformism. What’s up with that?

On my current understanding, coolness is status countersignalling. If a low status guy shows up to school in a clown suit, it’s mildly cringe and low status. If a sufficiently high status guy shows up to school in a clown suit, it’s a statement: it says “I am so high status that I can show up in a clown suit and nobody will confuse me with a low status guy”. It therefore reinforces high status. That dynamic is what coolness is centrally about: it’s being sufficiently high status that one can do normally-status-lowering things, and it only serves to reinforce one’s high status.

… which is easier than it sounds.

We no longer live in the tribes of ~150 people for which our instincts evolved. Modern humans spend far more time than our ancestors around people who we do not know well—people who we’ve never met, or people who we’ve seen before but never talked to, etc. Which means that our social status is much more flexible than we instinctively feel! In a setting where most people do not know each other well, status is mostly guessed from appearance and bearing and presentation, as opposed to memories of past interactions. Change your appearance and bearing and presentation, and you change your status.

How to Pull Off The Clown Suit

Above all, one must wear the clown suit confidently. Remember, the clown suit is meant to make a statement: “I am so high status that I can show up in a clown suit and nobody will confuse me with a low status guy”. When someone honestly feels that in their bones, knows in their heart that they really are that high status and can pull it off… what do they feel while strutting about in the clown suit?

Proud and smug. They feel a little proud, because they know full damn well that they can pull off the clown suit. Not only are they not hiding, they want everyone to see it. And they feel a little smug, because they know that other people can’t pull it off.

You need to feel the pride and the smugness, and you need to let them leak a little. Let the people see that you’re not just not ashamed of the clown suit, you’re proud and smug about the clown suit. Don’t flaunt it; flaunting is itself a hallmark of low status. You’re not that desperate. Just leak a little whiff. And when people notice that whiff of pride and smugness, they’ll subconsciously think “damn, that guy must actually be really high status”. Even if they’d otherwise have tagged you as low status, once they catch that whiff they’ll be worried that you know something they don’t.

Looking Good

Admittedly, leaking a little pride and smugness is not sufficient by itself to make the clown suit cool. It’s usually the final bottleneck and the biggest component, but there are other necessary elements.

Remember: in a setting where most people do not know each other well, status is mostly guessed from appearance and bearing and presentation. If one flubs the other aspects of appearance and bearing and presentation sufficiently badly, then the whiff of pride and smugness will come off as delusional.

Obviously, being physically attractive is a big piece. As a general rule, for both sexes, the lowest ~third of attractiveness ratings are defined mainly by being visibly overweight. (You can see this e.g. by glancing at Aella’s posts on face ratings.) If you are visibly overweight, it’s going to be a hell of a lot harder to pull off coolness in person. Not impossible, but a lot harder.

On the other end of the spectrum, if you are a visibly jacked male or visibly hourglass-shaped female, with clear skin and a symmetric face… coming off as cool in person is likely to be very easy. You can be missing other standard pieces and still pull it off.[1]

Then there’s presentation. All the usual skills of charisma are relevant in person, and even in writing (like this post!) many remain relevant. It’s a lot easier to come off as cool if you’re an engaging conversationalist/speaker/writer. That’s a topic with a lot of depth, so I’m not going to try to go into here; if you want to learn those sorts of social skills to an unusually high skill level, pick up artists are a useful source. They have very good feedback loops and many of them love to spread what they’ve learned. Personally, the single largest boost to my social skills came from an hour-long talk/workshop twenty years ago, which (I only later realized) was basically PUA-101 but with the sex/escalation parts stripped out so that it was focused on general-purpose social skills.

Finally, of course, appearance is largely about clothes. And because useful nonconformism does not usually involve literally wearing a clown suit, clothes are one of the main tools we can use to signal coolness.

Dressing The Part

You probably already have some intuitions for coolness of clothes. Leather jackets and sunglasses are cool. A suit and tie is high status, but usually not cool. An old poorly-fit t-shirt is neither.

Isn’t it kinda weird that there are standard wardrobe items which signal coolness, if the whole point of coolness is to be nonconformist in order to countersignal?

The system works mainly because the suit and tie exist. Many institutions offer status in exchange for conformity, and the suit and tie are the wardrobe component of that deal. The people who take that deal do not have the option of leather jacket and sunglasses; if they stop conforming with the suit and tie (among many other things), they lose their status. So, wearing a leather jacket and sunglasses can signal nonconformity, even though the leather jacket and sunglasses is itself a standard outfit.

Crucially, the leather jacket and sunglasses also signal status. If someone doesn’t look confident enough or attractive enough, a leather jacket can come off as trying too hard, rather than cool.

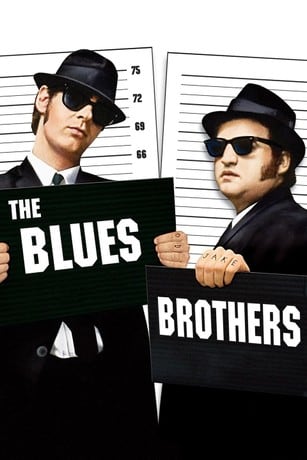

Of course, there are lots of other options besides literally just a leather jacket. As a general rule, any outfit which makes people ask “are you in a band?” signals coolness. Personally, I usually wear all black, including suit pants and jacket from a tailor in Shanghai[2], Converse sneakers, a black hat, and sunglasses. People ask me all the time if I’m in a band, and say I look like either The Blues Brothers or Kid Rock.

On the flip side, if you’re aiming for coolness, you probably want to avoid dressing too conformishly, even if the outfit is high status. Don’t go standard suit and tie. If people are reading you as conformishly high status, then it’s going to come off as weird when you start nonconforming. You want your clothes to broadcast in advance “I’m going nonconform as a high status countersignal”. Remember, you’re a little proud and smug about it, you want them to know about it and see it coming. You’re not one of those suit and tie losers, and you want it to be obvious to everyone that you’re not one of those suit and tie losers.

Beyond Nonconformist Takes

If you’re secure in your coolness, and accustomed to treating normally-status-lowering moves as countersignals, it unlocks other epistemic benefits.

For instance, I have occasionally been known to update in realtime in conversation, when I’m wrong about something which I’ve defended at length previously[3]. Internally, a load-bearing part of that is “I must not be seen hesitating to make this obviously-correct but normally-status-lowering move, because hesitating would mean I’m scared to lose status and therefore not securely cool”. My felt social pressures flip from “I must not update” to “I must not hesitate to update”.

More generally, countersignalling can flip the sign on social perceptions. Saying the thing everyone was thinking might flip from cringe to chad. Taking a risk might flip from a sign of desperation to exactly what was expected. Emotional vulnerability might flip from a sign of weakness to a sign of bravery.

… and conveniently, when one does conform, people rarely notice. So there’s an asymmetry in those sign flips: it’s cheap to ignore most cases where a sign flip is inconvenient.

Coolness is a foundation which allows a lot more social freedom.

- ^

As with the clown suit, if you’re attractive and you know it, you should feel a little proud and smug any time you get a socially-acceptable excuse to be naked or scantily clad around other people. If any of you were at Metagame 2025 last weekend and saw me taser-knife-fighting in my underwear in the central courtyard at Lighthaven, now you know why I feel totally fine with taking my clothes off in public.

- ^

Getting your clothes tailored or adjusted to fit properly is probably the single highest-value thing you can do to look good via clothing.

- ^

Nate vouches for such an occasion here.

With no shade to John in particular, as this applies to many insular lesswrong topics, I just wanna state this gives me a feeling of the blind leading the blind. I could believe someone reading this behaves in the world worse after reading it, mostly because it’d push them further in the same overwrought see-everything-through-status frame. I think it’s particularly the case here because clothing and status are particularly complex and benefit from a wider diversity of frames to think of them in, and require diverse experiences and feedback from many types of communities to generalize well (or to realize just how narrow every “rule” is!)

I’m not saying John has bad social skills or that this doesn’t contain true observations or that someone starting from zero wouldn’t become better thanks to this, nor that John shouldn’t write it, but I do think this is centrally the kind of article one should consider “reverse all advice you read” for, and would like to see more community pushback and articles providing more diverse frames on this.

I’m confident I could sensibly elaborate more on what’s missing/wrong, but in the absence of motivation to, I’ll just let this comment stand as an agree/disagree rod for the statement “We have no clear reason to believe the author is actually good at social skills in diverse environments, they are writing in a seemingly too confident and not caveated enough tone about a too complicated topic without acknowledging that and are potentially misleading/short term net negative to at least a fifth of lesswrong readers who are already on the worse side of social skills”

I think one important caveat the post didn’t mention is that dressing in a clown suit is likely to be polarizing, and there’s a selection bias in that you’re likely to get positive feedback from the people who like it, while the people who are privately rolling their eyes at you will say little. Increasing the variance in how you’re received can often be a fine tradeoff to make, but you should be aware of the fact that you’re making it!

E.g., I used to routinely dress pretty weird and mostly only got positive compliments for it (including from random people on the street), which felt quite cool and good for my self-esteem. Then I happened to mention in one conversation that “yeah, I dress weird, but nobody seems to react negatively” and one person volunteered something like “actually, when I first saw you, I did assume there was something wrong with you and it affected my opinion of you negatively, though that did get corrected when I observed more of you”.

I think there’s a bit of a “no free lunch” element in status interactions, in that if something gets you points for being seen as unusual and courageous, typically the reason why it’s unusual and courageous is that some people will, in fact, deduct you points for it. Now you might still earn more points on average than you lose, but it’s something to keep in mind.

Somewhat relatedly, when I started growing my hair long, I got exclusively positive feedback about it. It would have been easy to take this as evidence that clearly this was a good decision and this is just the better hair style for me. But then again, personal feedback like this tends to be very strongly filtered. Firstly, as in your example, the vast majority of people who disagree will just say nothing rather than telling me “I think this looks worse than before”. Secondly, there were a few cases where people saw me after a longer time, said something like “Oh, your hair is longer!” and then after a brief pause added something like “Looks good!”—I suspect many of these cases were just the person realizing that pointing that out without giving a compliment would seem rude or awkward, so they quickly made sure to say something nice about it.

Oh yeah, that actually reminds me that after not cutting my hair for several years, I recently did cut it. That gave me the chance to notice that when I had long hair, various people told me it looked good—and then after I cut it, different people told me that I looked good for having cut it shorter. But at no point did anyone say “your hair looks bad now”. (Actually no wait, one person did say that my hair was “ruined” now that I cut it, but that person was also ten years old.)

Fwiw., my hair grew longer and people often point that out, but never has anyone followed with “looks good”.

Then let me be the first one to (honestly) say that you do look good in long hair.

+1 to this. Tying it back to coolness specifically: coolness will absolutely alienate some people. That is not just an unavoidable side effect, it’s load bearing for the game theory to work.

Trying to offend as few people as possible leaves one looking generic, or like a politician/middle manager.

As the opening of the post points out, nonconformity is a strict requirement for better-than-baseline epistemics. If one is trying to offend few people in general, then one’s epistemics are doomed to basically-baseline. So I don’t recommend that goal.

One could still argue that looking generic and inoffensive is fine, so long as one’s beliefs aren’t under lots of conformity pressure. But man, I sure would be very skeptical if someone claimed that were true of themselves.

There’s also the aspect of target audiences. There’s the baseline of looking like everybody else (though of course there isn’t any single baseline, and it changes over time, etc.). Any divergences from this will grant and deduct points from different groups. This should be fine as long as you’re gaining points from groups which you value, and losing points from groups which you don’t care about.

I think I agree with this. To illustrate: When I met John (which was an overall pleasant interaction) I really did not think that the hat and sunglasses looked cool, but just assumed this was Berkeley style idiosyncracy. Usually I would not deem it appropriate to comment about this publicly, but since it was used as an example in the post this feels like a relevant enough data point to bring up.

I don’t have this feeling. I wouldn’t say that this is the full and final analysis of fashion, but I think the kind of analysis done in this post is very aware of social signaling games in a way that is very hard to find anywhere else on the internet, and so a pretty good contribution to people’s understanding of fashion for that reason.

I for one would be interested in hearing an elaboration.

Strangely, just after reading this post somebody happened to link me to this Tumblr thread:

By all means wear what you want, but the positive reactions you get from strangers who directly approach you are not necessarily an accurate way to gauge how most people are reacting to your outfit. You’re sampling from the population of “people who have spontaneously chosen to engage with you”.

Generally when you wear a polarising outfit people who dislike it won’t go out of their way to tell you. I’m extroverted enough that I will (very occasionally) complimented strangers in public on nice/unusual outfits, but I’ve never told a stranger their outfit is bad.

”I inevitably get weird looks from the kind of people who think having a tattoo is an affront to god but they give me that look for just existing with blue hair and pronouns too”

This line in particular just seems like bad epistemics. Is it really likely that everyone who reacts badly to their outfit would also judge them for having coloured hair?

I think a potential drawback of this strategy is that people tend to become more hesitant to argue with you. Their instincts tell them you’re a high-status person they can’t afford to offend or risk looking stupid in front of. If you seem less confident, less cool, and less high-status, the mental barrier for others to be disagreeable, share weird ideas, or voice confusion in your presence is lower.

I try to remember to show off some uncoolness and uncertainty for this reason, especially around more junior people. I used to have a big seal plushie on my desk in the office, partially because I just like cute stuffed animals, but also to try to signal that I am approachable and non-threatening and can be safely disagreed with.

+1 and this seems like an important failure mode John was hitting hard for me until I realized how bad his social skills are a few months ago, at which point I realized I can interact with him like an autist. He isn’t advertising that well imo; guessing his opinions by interpolating between autistic people I’ve known, I doubt as many people updated on his recent posts as he might intuitively expect.

I mean, I am in a sense a weird edge case, due to my weird mix of education/experience levels at different things. But I figured it was worth mentioning.

This just seems false to me honestly. You just have to signal in public that you’re willing to be authentic, that you’re not going to retaliate against those who come after you (I.e. try to change your mind in constructive ways), that you’re actually willing to change your mind (by actually doing so on minor points), and so on.

Status is power and people with power are more likely to be trusted if they don’t misuse that power in public.

For a more specific example, I am currently on hunger strike in protest of ASI, and there are people still willing to debate AI risk with them. I am not yet so polarising that people avoid the topic entirely.

That can go too far though, as you can then be viewed as the weird person with the seal plushie, which now means you’re harder to approach and somewhat threatening because you’re different from others, which implies there might be potential difficulties with communication or whatever and so maybe it’s better to avoid you, or not, because then I’m the one being weird… I’ll just go and talk to Bob to avoid all of this.

Or something like that.

Yeah, per Kaj’s no free lunch thing https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/WK979aX9KpfEMd9R9/how-to-dress-to-improve-your-epistemics?commentId=Q3do78rjEk6mrrtKf

Suits can be cool and nonconformist if they’re sufficiently unusual suits. >95% of the suits you see in America are black, grey, or dark blue. Usually it’s with a white or pale blue plain shirt. Nowadays, neither a tie nor a pocket square. Boring! If you have an even slightly offbeat suit—green, a light color, tweed, seersucker, three-piece, double-breasted—particularly if you have interesting shoes or an interesting tie—however you may look, you don’t look like you’re trying to fit in.

Ivy Style Any% Speedrun Complete

I really think this is a case where one needs to provide pictures of themselves for this to be taken seriously. Similar to my preference that people “post body” if they’re giving advice about fitness. I want to see proof of work. The brief self description doesn’t sound cool or high status at all to me, and it seems counterproductive to take advice on coolness and status from someone that might be uncool and low status

This is an instance where I think the ambiguity between prestige status and dominance status is unfortunate, and I’d have written it with a straight up s/status/prestige/.

Well, unless you’d argue that dominance status is involved, in which case nevermind this

I think dominance status is involved. A lot of people would feel uncomfortable wearing unusual clothes in public because they’re afraid of drawing attention to themselves, due to some kind of “people who stick out get beaten down” fear that’s related to dominance dynamics. And they’d be especially afraid of showing the kind of slight smugness described in the post, as that could be construed as a provocation (I think smugness is dominance in general).

This is fascinating. Let’s think a little more about whether this really improves your epistemics. It reduces bias to fit in, but increases bias to “act cool” in ones’ beliefs. I’m not sure that’s better.

What about being conformist half the itme and anti-conformist the other half, to balance it and try to become conscious of your attitudes and resultant biases?

Also, I’m going thrifting for offbeat clothes. I do dress to conform most of the time and to anti-conform part of the time. I might step that up.

There are lots of options in the possibility-space. But are there lots of options on the actual market?

Fashion industry is one of those things that makes me want to just go do it all myself in frustration.[1] The clothing-space seems drastically underexplored.

The most obvious element is coloration. For any piece of clothing, there’s a wide variety of complex-yet-tasteful multicolor patterns one might try. Very subtle highlights and gradients; unusual but simple geometric patterns; strong but carefully-chosen contrasts. You don’t want a literal clash-of-colors clown outfit, but there’s a wealth of possibilities beyond “one simple color”; e. g., mixing different hues of the same color.

Yet, most items on the market do just pick one simple color. Alternatively, they pick a common, basic (and therefore boring, conformist) pattern, e. g. plaid shirts. On the other end of the spectrum, you have graphic tees and such, which are varied but are decidedly unsubtle and, in my opinion, pretty lame (outside very specific combinations of design and social context[2]).

You can slightly deal with that by wearing several items of different colors that combine the way you want. But this only allows basic combinations, and the ability to do that becomes very constrained in hot weather.

Eagerly awaiting the point when AI advances enough for me to vibe-design and 3D print anything I can imagine.

Also the bag industry. You’d think the wealthy community of digital nomads would’ve incentivized a thriving ecosystem of varied, competently designed modular bags, and yet.

This is obviously peak fashion.

This guy certainly knew how to wear the clown suit...

True, but it’s not a central example of a clown suite. It’s a relatively normal (but shabby) suit with non standard colours along with face paint and dyed hair. The Joker would come off a lot different looking like this (first random image I found).

So more like this guy, then?

Your link broke for me, I shortened the URL to this and it worked.

Thank you!

Here I just thought that was your superhero costume

Can you provide specific examples of places where this fails predictably to illustrate? Better: can you make a few predictions of future failures?

If I understand correctly, your position is that we lose status points when we say weird (as in a few standard deviations outside the normal range) but likely true things, and it’s useful to get the points back by being cool (=dressing well).

It seems true that there is only so much weird things you can say before people write you off as crazy.

Do you think a strategy where you try to not lose points in the first place would work? for example by letting your interlocutor come to the conclusion on their own by using the Socratic method?

That is not my position.

Being cool is a specific social strategy (not synonymous with dressing well). The nature of that strategy frees one to do a lot more nonconformist-signalling things, without losing status each time, because doing nonconformist-signalling things is an expected part of people playing a “cool” social role.

Smugness and confidence are important, because they signify that you know what you’re doing, and if someone else doubts it, they’re in the wrong. Basically the Emperor’s New Clothes. If you can pull that off, you’re sort of by definition high status. People might privately think there is something wrong, but as long as everybody else pretends that it’s fine, and even very good, then you’re not going to step out of line.

Part of being cool is being legible. A leather jacket is legibly cool—add enough confidence and ease, and you have a good chance of being viewed cool. Unless you’re over 25 and not obviously hot, in which case you’re trying too hard / a poser. Which can happen anyway, as wearing a leather jacket to show you’re cool is so 90s (or whatever).

That Midjourney image is a good one. That guy is adding clown elements to an otherwise normally good looking suite setup. He’s wearing clothes (and importantly accessories) that are legibly “well dressed” and then added the dots and facepaint to show that he’s edgy and cool.

I think this is the main point of the lonely dissent article—wearing a leather jacket (or a black beret, or reading the communist manifesto or any other of a bunch of such things) are signs that you’re not like other girls, you’re not a sheeple, you’re the chosen or whatever. You still care about what others think about you enough to present yourself in ways that are legibly going against the system (or popular opinion, or what <some group> thinks, or whatever). While showing up in a clown suite because you have a good reason for doing so that doesn’t at all involve what other people think (even if it’s just because you want to) is non legible and strange.

Coolness is very much inside the limits of what is socially allowed, it’s just up against the borders. The further you get without crossing over, the cooler you are.

I showed this video (for lack of a better picture of you) to someone who is attuned to these kinds of things. She says you have a good looking face, so you can get away with a lot more, but that your sunglasses are a choice. Which sort of confirms your whole point, I suppose...

I wish someone (on lesswrong) who understands how fashion works on a nuts-and-bolts level would write this down. I’ve spent the last year (and a lot of money) on a bunch of outfits, and watched/read some fashion guides for guys, and can’t put my finger down on anything but the basics (match colors, collars are better than no collars, etc..)

The feedback is very sparse (coworker complimenting a dress, more smiles from strangers when I’m outside, etc) and all the sources I’ve read feel like pseudoscience. And yet some people have consistently good style—how do they do this? I now have 8 outfits that I can cycle through during dates etc, but surely this could be improved.

FWIW, this is generally true for design things. In web-design people tend to look for extremely simple surface-level rules (like “what is a good font?” and “what are good colors?”) in ways that IMO tends to basically never work. Like, you can end up doing an OK job if you go with a design framework of not looking horrendous, but when you need to make adjustments, or establish a separate brand, there really are no rules at that level of abstraction.

I often get very frustrated responses when people come to me for design feedback and I respond with things like “well, I think this website is communicating that you are a kind of 90s CS professor? Is that what you want?” and then they respond with “I mean… what? I asked you whether this website looks ‘good’, what does this have to do with 90s CS professors? I just want you to give me a straight answer”.

And like, often I can make guesses about what their aims are with a website and try to translate things into a single “good” or “bad” scalar, but it usually just fails because I don’t know what people are going for. IMO the same tends to be true for fashion.

Almost any piece of clothing you can buy will be the right choice in some context, or given some aim! If you are SBF then in order to signal your contrarian genius you maybe want to wear mildly ill-fitting tees with your company logo to your formal dinners. Signaling is complicated and messy and it’s very hard to give hard and fast rules.

In many cases the things people tend to ask here often feel to me about as confused as people saying “can you tell me how to say good things in conversations? Like, can someone just write down at a nuts-and-bolts level what makes for being good at talking to people?”. Like, yes, of course there are skills related to conversations, but it centrally depends on what you are hoping to communicate in your conversations!

I still think there’s a science to it which is yet to be properly written up. It’s not at the level of “this combination of design choices/clothing elements is bad, this one is good”, but there is a high-level organization to the related skills/principles, which can be taught to speed up someone learning design/fashion. They would still need to do a bunch of case studies/bottom-up learning afterwards (to learn specific extant patterns like “the vibe of a 90s CS professor”), but you can make that learning more sample-efficient.

Social skills are a good parallel. Actually talking to people and trying to accomplish different things with your conversations is necessary for developing social competence, but knowing some basics of the theory of mind and social dynamics is incredibly helpful for knowing what to pay attention to and try.

I know you (literally and explicitly, in similar words) say it, but this is also true of fashion and fashion advice; you are choosing what message to convey, not whether to convey one.

In the post it says:

I have nothing against John and am not commenting on John. However, there were multiple kids at my highschool who thought they would dress like they were in a band and then they’d be cool. We thought these kids were losers, because they acted like aliens with self-esteem issues looking for hacks that would make them cool.

A different way to think about fashion is to ask “What do I want people to think of me?” and “Who do I think of that way, and how do they dress?”. If you want to look cool, you should be thinking of people who are cool and how they pick their clothes, not wearing sunglasses at night[1].

Just like how websites can choose to look like Facebook or like Youtube or a ’90s computer science professor, in fashion there are a thousand ways to look cool and you need to select the appropriate style. Don’t dress up in a snazzy suit to volunteer washing oil off of ducks, don’t wear your leather jacket to a wedding, and maybe throw some faux-minimalism on your website if you’re trying to make it look trendy.

You have to find your niche though! The explicit moral of this comment is have an intended message.

Personally, I would always recommend dressing in high quality clothing[2] that is conspicuously not trendy (not bad looking, just not stuff that signals having just been bought) and that fits you well. This would be really bad advice for some subcultures!

Note: “coolness”, specifically, in fashion often comes from violating some rule, which means anyone wearing Standard Cool Garb looks more like a James Dean wannabe than anything else

Don’t complain about it being expensive just yet: if you’re in the US, somewhere a mile away from you, a resale store is hanging up clothes amounting to hundreds of dollars in sticker price and charging dozens of dollars for it.

What I’m about to say is incomplete, will probably be made up of things you already know, and may sound like pseudoscience. Nonetheless it is true and if you do not learn it then you will probably never feel that you have improved your fashion sense.

Fashion, like all forms of personal art, is a language. The way you dress is essentially a form of social signalling. And social signalling is good! Even if you prefer not to signal to others, unless you are unusually (like top hundredth of a percentile) insulated against the culture you grew up in, you can socially signal things about yourself to yourself.

Also like all forms of personal art, fashion is subjective. There are several large schools of thought and subcultures, there are novice and expert practitioners whose language and aesthetic sense barely overlap, even though they may be connected by a complex set of social streams. An outfit simultaneously picks an audience and says something to that audience. If you wear a lot of baggy, ragged clothing, maybe graphic tees, particular brands of sneakers, you are communicating a particular sort of belonging to a particular karass.

And like all languages fashion is difficult to learn, and impossible to master, formally. You must develop your own aesthetic sense, there simply is no substitute. An outfit that looks great on someone else might make you look awkward, out of place, confused, because there are forms of communication that are hard to put into words and they cannot be naively duplicated.

I recommend the following exercise to quickly develop a heuristic fashion sense. It could take anywhere from five to ten hours and may be fun.

First, watch some runway walks from fashion shows. (The language of fashion is intensely gendered—to understand men’s fashion, watch male models.) For each outfit, write down (I recommend physically doing this) some details about the outfit (how does it fit? What is the silhouette like? Colors? Layers?), some aesthetic impressions (is it passive or aggressive? Warm or cold? Salty or sweet? You don’t have synesthesia but pretend that you do, let your brain make associations. You have latent connections in your head, we’re trying to figure out what they are). Notice how the models walk—does their body language seem to accentuate certain parts of the outfit? Is it fluid and free, is it rigid, is it aggressive, is it confident? For each outfit, write down two sentences: one, what you think the outfit is trying to communicate (Maybe something like “I let life come, and it always turns out right” or simply “Don’t fuck with me”) and what it actually communicates to you personally. Since it’s a fashion show, you should expect that the outfit is signalling its core message as loudly as possible, so be bold.

Once you’ve done this for, say, 20 outfits, once you start to feel like you’re gaining some sense for what you’re going to write before you write it, do this for outfits in clothing catalogues (you’ll notice the messages centralize to things a broad audience might want to communicate!) Then for the outfits of people around you in real life, maybe even in your social circles. Then for outfits you put together out of your own wardrobe.

Once you have at least a little facility with the language of fashion, you’ll have a better sense for how to put an outfit together, how to recognize and handle clashing elements, how to think about silhouette and fit, etc. When you put an outfit on, you’ll have some sense for what it’s trying to say, and you’ll probably find yourself embodying the outfit a bit more. You will both put together better outfits and wear outfits in ways that make them look and seem better, to yourself and to those around you.

External feedback is useful but not reliable. If you don’t have an internal sense for why you want to wear one thing and not another, external feedback is useless to optimize for, because you won’t actually understand what you’re optimizing for. Develop your taste first, nothing can happen without that.

If anyone does this exercise, I’d be very interested in people sharing what they thought various outfits said, to see if different people converge on similar answers. Whether-or-not-this-is-pseudoscience seems to hinge entirely on that question, and it’s very testable.

Preregistering that I don’t think this is true. I expect mild-to-strong agreement about intentional and complex pieces, i.e. in the fashion show example, but generic pieces are a contested zone—two fashion cultures will tend to have wildly different interpretations of the meaning of a monocolored t-shirt, for example, and this is by design. A quiet outfit that means one thing to the wearer, in the loose sense of meaning we’re using here, could be gibberish to somebody with a different aesthetic sense, or could even mean something completely different. (Indeed this is how “counterculture” usually works—imagine a conlang which matches English in vocabulary and grammar but not in word meaning, a language which is deliberately built to make English ambiguous.) I expect agreement among similar people (even without discussion), but not among different people except in clear-cut cases.

Accordingly, note that I’m making a weaker claim than perceived: I do not thing fashion has or can have universal meaning unless you’re wearing an extremely stereotyped outfit. If you want to get better at fashion because you want to unify external perception, I expect this to fail unless you want your perception to be a stereotype (scene clothes, suit-and-tie, fedora and neckbeard).

That would be roughly my recommendation: pick a universally-recognizable archetype and channel that archetype real hard. (This generalizes beyond “coolness” to other goals.) Otherwise, you’re just sending messages which are in-practice far more ambiguous and weak than you think to an audience which is small to begin with, and probably the number of people who will actually recognize what you intended the clothes to say is approximately zero.

Ah I think we disagree strongly here, this advice seems disastrous in basically all cases. Channeling an archetype very hard without deeply understanding that archetype makes you look like somebody who really wants to be perceived in a particular way, which makes it hard to be perceived in that way. See fedora neckbeard style. Some archetypes are formal and harder to mess up with lack-of-understanding, basically everybody can buy a nice suit with some research and lots of money, but even then, people who wear suits without understanding what a suit signals can be off-putting. The harder you try, the better your execution must be to get credit. Confidence is not enough, non-conformity on its own is not enough, you simply can’t do fashion in negative space.

Also see my point about sending messages to yourself—if you have an individual taste, then:

(1) You can use that taste to send signals to yourself, which is much better than sending them to others. I.e. if you have a sense of what a smart, kind person dresses like, then dressing like that is an effective reminder to be kind and smart.

(2) Even if people don’t share your taste they will often be able to recognize that your style is syntactically correct, and will give you social credit for this. Gibberish is often distinguishable from prose is distinguishable from poetry even in languages you don’t speak. Incidentally, I think this is an axis of coolness that you miss, and might even be the dominant axis.

(3.1) People will come to understand your taste better as they get to know you better, so you will get the strongest signalling effects on those you care the most about signalling.

(3.2) Since people like being in on social signalling, you will attract positive attention from those who get the most benefit from grokking your style. People too different from you will think it’s too much effort, people too similar to you will think it’s too easy, so dressing according to your own taste draws in people who share intuitions but not thoughts with you. These are the best people to know.

I mean, yes, obviously you need to understand the archetype deeply in order to channel it real hard? Ok, I suppose the existence of neckbeards indicates that that is not obvious and I should be explicit about it. But yeah, as with most things, one can certainly shoot oneself in the foot by not understanding what one is doing.

I guess you’re imagining that the advice would be “disastrous in basically all cases” because basically everyone who tries it will execute incompetently rather than competently? I’m not sure why you think that, “basically all cases” seems way too strong here. There are, for example, probably people who already understand the relevant social signals and are capable of competent execution, but either haven’t thought through what would actually benefit them most or haven’t been brave enough to actually do what would benefit them most.

Regarding your four specific points:

I totally buy the “signals to self” value proposition.

I also totally buy the “syntactic correctness” point, though I wouldn’t frame it that way in my head. Coherence of a look is recognizable and valuable even when it’s unclear what signal it sends.

The people who get to know me better are the least important for my clothes to signal to; they have loads of other data which will largely overwhelm my clothes. Clothes are most important for signalling to the people I know least.

I think you are vastly overestimating the amount of effort which other people will put into grokking one’s style, regardless of whether their taste is similar to one’s own. Especially since the people I care most about signalling to with my clothes are exactly those who I know least.

On a meta note: I’m responding to most of your points because I find this discussion interesting. But I know a dense thread like this can be tiring, so please don’t feel too obligated to respond if you find it draining.

Addressing the last first: No worries, we’re in the same boat here. Fortunately (unfortunately?) I am a sort of person who cannot actually run out of energy for detailed online dialog as long as the other person is thinking and raising interesting points, so feel free to respond as you see fit (and of course to ask me to explain differently or be less verbose if that’s easier for you, I think we’re both benefiting from this exchange and want to keep it that way.)

Something like this is my view, yeah. There’s a relevant selection effect: plenty of people would benefit from just trying to emulate an archetype, but these are mostly people who are good at picking up non-verbal communication, so will learn a lot by just trying an outfit, noticing how they are perceived, repeating. The fashion advice I think people like this need is usually “care more about fashion”, sometimes “be more generous to yourself in your presentation”. But if you tell a person like this to just wear a bold established outfit and go from there, they’ll ask why they should care about what they wear, and if you can convince them to care, the explanation you give here could have been given in the beginning and they would get the same benefits.

Disastrous in all cases was an overstatement and I retract it, I should have said that I imagine this being disastrous when it’s impactful, but for most people it would not be impactful. One reason to believe this is that this is already what people do when they become interested in fashion. People tend to dress more “noisily” when they don’t have a sense of their ideal look yet, they mimic something they’ve seen. Maybe there’s an untapped group of people who have built intuition for fashion but aren’t brave enough to use it; I tend to think that lack of courage stems from lack of mastery, and a person who already has taste will feel just as fearful putting on a bad outfit as a good one, so why not choose a good one?

(I should note that it’s possible that I’m missing out on some groups of people here—if there are lots of people like you describe, who could basically dress well if only they tried to, they’d be hard to pick out for me. My model of fashion doesn’t predict that there should be many people like this, but in this arena it would be hard for me to falsify, so I’m largely explaining a prior here.)

Re points 3 and 4: I think I have two disagreements here? Mostly I’m speaking from personal experience, let me know if you think I’m miscalibrated as a result. But I don’t interact much with people I don’t know, so while wearing a noisy outfit might send strong signals to lots of people, those signals tend to be useless to me, I can’t follow up on them. By choosing colors and silhouettes and layers that make sense to me on a particular day, though, I can somewhat-reliably show my friends that I’m feeling energetic and we should do something interesting, or I’m feeling cozy and we should stay in and laugh together, and I can interpret the same from their outfits. We could of course establish these things verbally, but this would be more time-consuming, and verbal language is not well-fitted for such discussions. If you intended to wear the same thing every day this would change.

It’s also possible that I’m overestimating willingness to understand style, but I’ve made several friends and had more interesting conversations that started because of interest in another person’s outfit (or my own outfit), and I imagine most people (mostly women tbf) have had the same experience. This is more art than science; I rarely think that I want to learn another person’s style language, but I often like their ‘vibe’ and believe upon reflection that their clothing was the foundation of their vibe.

I want to dig in on this. You of course have much more visibility into your own experience than I do, but just going by that description, my first guess would be that there’s a different thing actually going on.

Notably, “how energetic is <person> feeling” is one of the easiest things to read off of body language and speech patterns. There’s usually a pretty clear energy level being broadcast.

My guess would be:

you sometimes choose an outfit to match your intended energy level for the day

that outfit mostly acts as a self-signal, reminding you of your intended energy level for the day, so you act more in accord with that intended energy level

your friends then notice your energy level from all the clear nonverbal cues being sent, most of which is not the clothes themselves.

In particular, one prediction this model makes is that if you dress low-energy but feel/act high energy, your friends will mostly pick up high energy vibes rather than low energy vibes. They might not even notice the clothes mismatching the vibes.

Curious to hear how well that does/doesn’t feel like it fits your experiences.

I disagree with this model in multiple ways. I don’t currently have a short summary of that disagreement, so I’ll hit a bunch of points which might gesture in the right direction:

I expect that even people who are relatively good at picking up non-verbal communication will either get very few bits on how they are perceived (e.g. just general positive/negative valence and strength), or (more often) hallucinate a perception which is not there. The thing you’d want to get a read on is, like, what story/role/narrative the clothing is perceived as conveying, and that’s a relatively hard thing to get from a nonverbal read.

I don’t imagine feedback from other people being the main tool anyway. Like, the core way I imagine someone not falling into the neckbeard trap is by looking in the mirror and honestly asking themselves “does that person in the mirror actually give the vibe I’m looking for?”. The hard part is to pay attention to one’s gut and give an honest answer (and different people will be differently biased in that regard).

I guess feedback from others could substitute for the “look in the mirror”, especially if one does not trust oneself. But that substitutes trusting the feedback from others, which is itself tricky. Either one needs nonverbal reads on relatively detailed things like perceived story/role/narrative, or one needs to ask for verbal feedback in a way which both elicits the relevant information (which may be hard to articulate at all) and elicits honest answers.

Insofar as one does rely on feedback from others as a main driver of fashion choices… man, that feels like a trap. Someone who iterates on that feedback is going to shoot themselves in the foot, by e.g. doing things which offend nobody and therefore just look generic, or by doing things which seem kinda vaguely nice but don’t send a coherent message at all, or ???.

When I imagine someone who “understands the relevant things but hasn’t been brave enough to use it”, a central example would be someone who can look in the mirror and accurately assess whether they’ve got the vibe they want, but has mostly optimized their wardrobe based on valence-feedback from other people, without a coherent story/role/narrative. I want to tell that person “pick a strong archetype, make the person in the mirror vibe that archetype, be honest when assessing yourself, then be brave and go rock it”.

Agree that this is the relevant experiment. I have unusually low body-language signalling intensity, so friends consistently could not read my vibe when I didn’t use fashion as a channel for nonverbal communication, but the self-signalling channel is hard to rule out explicitly. Not sure if the difference matters but I agree that the mechanism can be less straightforward here.

Regarding the rest, I agree that we have hit the main disagreement! (And it is difficult to articulate). I think it’s something to do with whether people who dress badly can tell why, or even that, they’re dressing badly. Your bullet points are all points of disagreement, most in straightforward ways, so I’ll only give voice to the interesting ones:

I think the neckbeard really truly believes that their outfit is vibe-appropriate. Perhaps more straightforwardly, the neckbeard agrees 100% with everything you’ve written thus far. When they notice negative reactions they tell themselves “well you can’t please everyone, and some people are bothered by anyone who stands out.” They put on an ironic graphic tee and a visor and a fedora and hold their katana and look in the mirror and think “fuck yeah I’m the coolest person ever, everyone wants to be like me.” (This is a fine thing to believe incidentally! I don’t have that much animosity for the neckbeard. But I think they end up confused and upset by the fact that people avoid them, and a better understanding of fashion could help.) What the neckbeard lacks is taste.

I think most people get lots of bits of information from incidental interaction. The way someone looks at you as you pass has very little informational content, but the difference between how you expect a first conversation to go and how it actually goes has a ton, and the average person can have lots of these if they wish. I don’t absorb these bits easily—I have some embodied cognition/theory of mind deviation that restricts me to just getting valence, which is why I had to do the exercise I recommended (or something like it, my way was less structured) to develop a fashion sense that I’m happy with. But in discussing fashion with others I’ve come to suspect that, like with body language, the things I discovered only by thinking very carefully are actually obvious to most people upon reflection.

Maybe a concrete deviation: It seems like you see fashion largely through the lens of offensive vs. nonoffensive? At least this seems to be the main failure mode you describe, when talking about how an outfit can fail. I do not think this is a useful frame—in my aesthetic language I call this quality “noise” (are we talking about the same quality?), the tendency of an outfit to attract attention and invite judgment of any valence, and it’s only the fourth or fifth thing that I care about when putting an outfit together. Is it your intuition that people fail to be fashionable by failing to be appropriately noisy? This would explain why bravery is the main requisite virtue to you while being nearly irrelevant to me.

I buy that, but I think the cause is more like a motivated blindspot than lack of taste.

Let’s look at the classic meme:

This guy’s problem is not combining an ironic graphic tee with a visor and a fedora and a katana. The guy’s outfit is not the main problem. The guy’s taste is not the main problem. The problem is he weighs like 300 pounds. What he needs is Ozempic.

Now, what does that guy think when he looks in the mirror?

When that guy looks in the mirror, I think he’s telling himself that the outfit looks great, and he’s motivatedly-not-thinking about how overweight he is. He’s telling himself that the outfit puts him in the same bucket as a better-looking guy wearing that same outfit and facial hair.

That’s not a problem of lack of taste, that’s a problem of lack of self-honesty. He needs to be honest with himself about what he sees in the mirror.

I wouldn’t say that’s the main lens I use in my head, but that is an accurate description of a major failure mode, plausibly the most common failure mode.

(Aside: I’d prefer the term “loud” over “noisy”, because “noisy” is easily confused with noise in the sense of signal vs noise, and signal vs noise is a very central concept here.)

I don’t think the meme is representative here though—the guy in the meme is fat because the internet hates this kind of person and also hates fat people. Memes that negatively portray their subject portray the subject as fat. To me the archetypal neckbeard looks like this:

https://preview.redd.it/bf2cd8wm46t01.jpg?width=320&crop=smart&auto=webp&s=f11661e0c9dac5237c0bb43b6ab8e72c324d1e3f

This guy isn’t overweight, isn’t unattractive. He’s confident in his outfit, he’s smug, he’s trimming his facial hair just fine. He just thinks his outfit seems suave and intelligent, but it actually seems childish, patronizing, and incompetent.

And while weight is a relevant part of appearance, it can be separate from fashion. I think Jackie Gleason is the classic example:

https://vintagepaparazzi.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/news_2522.jpg

Not every outfit or silhouette would work on Gleason here even if scaled up, he certainly couldn’t pull off aggressively-uncool counterculture looks, but he manages to dress well (at least in my view) and isn’t just adhering to the dominant archetype. (Orson Welles was also fat and stylish)

Maybe put another way: under your model, can the guy in the neckbeard meme dress well? If not, it seems like you have a model of attractiveness, but not of fashion. If so, it seems like “pick an archetype and embody it confidently, bonus points for noncomformity” is not a good enough description of your model, and I wonder (1) what other components your theory has and (2) what relative weight you attach to those components.

Those are useful examples, thanks. I’m gonna come at this from a different angle, but first to answer this question:

Unsure, either “no” or “it would be hard enough that I have no idea how he’d do it”. I do not think that makes this a model of attractiveness per se, rather I think every outfit has some level of attractiveness required to pull it off (which, for the worst outfits, may be beyond the attractiveness of any actual human). As the relevant section of the post said, attractiveness and charisma are necessary conditions.

Now back to the main cruxy part.

Suppose the neckbeard you linked to looks in the mirror and, in complete self-honesty, gets the vibe that he looks awesome. Like, he imagines someone else who looks just like that, and his gut response is “that guy looks awesome”. Well, as long as he’s being honest with himself… his own reaction is in fact extremely strong evidence that lots of other people would agree that he looks awesome. It’s very unlikely that he is so unique in his tastes (or lack thereof) that nobody else shares them. There may be lots of people who hate it, but at that point it is plausibly just correct to respond “well you can’t please everyone, and anyone who stands out is gonna bother some people”.

Personally, at this point I would tell him that he’s farther than he thinks from the best he could be doing, but yes there are probably many people who will in fact get a pretty good vibe from that outfit (again, assuming the premise that his own honest read was that it looks awesome). So at that point it’s down to numbers: just how many people would think it looks awesome, and how many would be driven away? In that guy’s case, I’d guess the “awesome” camp would be in the minority, but not so rare that it would never make sense to take the tradeoff (“better to be loved by a few and hated by many, than for everyone to feel nothing” as the saying goes).

This is importantly different from the fat guy in the meme! For that guy, the number of people who think he looks awesome is going to be very close to zero, and probably even in his own head he needs to motivatedly-ignore some things about the guy in the mirror in order to think he looks good.

Main point of all that: insofar as one is honest with oneself, one’s own reaction/vibe to a mirror is damn strong evidence of other peoples’ reaction/vibe. Probably at least a large minority will feel the same reaction/vibe, even if one lacks the majority’s taste.

And for most people, whatever reaction/vibe they get will basically match the reaction/vibe most other people would get; by definition most people are in the majority. If most people have the relevant taste, then most peoples’ honest vibe from the mirror will reflect that, and in that case the neckbeard is in the minority. If most people don’t have the relevant taste, then most peoples’ honest vibe from the mirror will reflect that, and in that case it’s fashion twitter which would be in the minority.

I think this is our empirical disagreement, so I’m not sure if conversation beyond this point is productive, but I’m glad we’ve pinpointed it. Concretely, I think this:

is simply false, and is especially false for the sort of people who need fashion advice. There are some relevant nitpicks here, mainly that if reactions to an outfit are more than one-dimensional we shouldn’t expect a “majority” vibe to exist at all, but those only seem important because I think people are often very mistaken about how others receive us.

Beyond that there’s a mindset here that I think you should be wary of, or at least should emphasize more strongly so that others are wary of it:

This is plausibly correct, sure, but I don’t think it feels more correct in cases where it’s true compared to cases where it’s false. Naively chalking up another person’s negative impression of oneself to them being bothered by anybody who stands out is in my view the dominant failure mode for personality, it’s the thought-terminating cliche that stops disagreeable or reactively non-conformist people from performing useful introspection.

Earlier we talked about the information content of a person’s impression of one’s outfit. I expect that very few people can get enough bits out of people who strongly dislike their style to make reasonable judgments about why they bother some people. Thus the strength with which this response resonates is controlled more by one’s prior, which is controlled by these personality factors. Some people may need to hear this, sure, but I’d usually accompany it with “On the other hand, the most stylish people I know very rarely get strong negative reactions, draw a lot of positive attention, and are not optimizing for perceived status or polarization.”

This second point seems more like a values difference than an object-level disagreement, though. If the goal is to optimize for the number of people who see you as (ingroup-proximate + high-status) your advice becomes makes a little more sense, and I’d recommend approaching things differently but broadly adopting the more polarizing, counter-signalling approach (although this means you don’t get to choose the ingroup you’re proximate to! It’s just going to be Todd Phillips fans and co.) I just don’t think this is a worthwhile or efficient thing to optimize for in this medium, and I expect whatever you can accomplish in this way to not be worth the downsides.

I agree that a competent write-up on the (true) theory of fashion seems to be missing. The usual way to deal with such situations is to act like the neural network you are: find some big dataset of [clothing example, fashionability analysis] pairs, consume it, then reverse-engineer the intuitions you’ve learned. If there’s no extant literature on the top-down theory available, go bottom-up and derive it yourself. (It will be time-consuming.)

Left a long comment that largely agrees, but I want to add: Do not just passively consume data! Working with a huge unlabeled dataset can be useful when you know nothing about the structure of the data, but you do know something about the structure of your data. You don’t have to understand fashion that well to build a good curriculum, or to give yourself a better architecture, or to add some side terms to your loss function. As with real neural networks, if you know anything at all about your domain, then you will get faster results by incorporating that knowledge into your training structure.

Do you know of such a dataset? I’ve tried spending some time on Pinterest for “fashionable” outfits but didn’t find that productive

Honestly, not to sound like a fop, but if you trust yourself to moderate opinions you hear, go for something “old fashioned” like https://www.gentlemansgazette.com/ and learn some of the old-timey rules and then work forwards from there. Like many squishy disciplines, modern fashion is hopelessly complicated with 15 levels of counter-counter-counter-counter-counter-signaling, and going back to the basics can help.

Try to learn things like:

How do I know if a shirt fits?

What’s the basic mold than men’s outfits were built around (hint, it’s the suit) and how does the shadow of this hang over modern fashion?

Why do we care about “clashing” outfits, and how do I know if two pieces of clothing “clash”? What colors go together, what patterns go together, etc?

What materials exist, and how do I, personally, feel about including them in an outfit?

Seems like a good question to prompt AI with. Here’s what I got from Gemini 2.5 Pro.

“good style” by what metric of good?

Do you accessorize? Collecting some accessories that you genuinely like / enjoy / think are cool, and then wearing whichever combination aligns with your mood on a given day, is one of the easiest ways to elicit positive remarks from strangers.

It’s socially acceptable to remark positively on a recent choice that a stranger has made, but things start getting fraught when one remarks on things that aren’t recent or aren’t choices. Therefore, to dress in a way that’s amenable to positive remarks, it’s kind of the bare minimum to include some element which is clearly a choice today rather than your default. When someone dresses to blend in, it’s a signal of “please do not remark on my appearance”, so it can start feeling weird to do so.

For more concrete suggestions, if you’d like to tell me a bit about how you currently dress and what attributes you’re most proud of about your identity (appearance, personality, character, whatever), I’d be happy to offer some suggestions from which you might find a couple that resonate.

High status is something you can only control to a limited degree, especially when you are trying to do things that have an immediate effect rather than doing thigns that gain status in the long run. Acting confident certainly helps, but it won’t help by so much that you can get away with wearing a clown suit because you’re acting confident. What will happen is that instead of confidence making the clown suit work, the clown suit will make the confidence fail.

Fedoras aren’t quite clown suits, but still, you can see how they worked, which is “not well”.

None of the ideas you’re saying are completely wrong, but you’re wrong about how they balance against each other.

… did you read the section after that one?