Focusing

Epistemic status: Firm

The Focusing technique was developed by Eugene Gendlin as an attempt to answer the question of why some therapeutic patients make significant progress while others do not. Gendlin studied a large number of cases while teasing out the dynamics that became Focusing, and then spent a significant amount of time investigating whether his technique-ified version was functional and efficacious. While the CFAR version is not the complete Focusing technique, we have seen it be useful for a majority of our alumni.

If you’ve ever felt your throat go suddenly dry when a conversation turned south, or broken out into a sweat when you considered doing something scary, or noticed yourself tensing up when someone walked into the room, or felt a sinking feeling in the pit of your stomach as you thought about your upcoming schedule and obligations, or experienced a lightness in your chest as you thought about your best friend’s upcoming visit, or or or or …

If you’ve ever had those or similar experiences, then you’re already well on your way to understanding the Focusing technique.

The central claim of Focusing (at least from the CFAR perspective) is that parts of your subconscious System 1 are storing up massive amounts of accurate, useful information that your conscious System 2 isn’t really able to access. There are things that you’re aware of “on some level,” data that you perceived but didn’t consciously process, competing goalsets that you’ve never explicitly articulated, and so on and so forth.

Focusing is a technique for bringing some of that data up into conscious awareness, where you can roll it around and evaluate it and learn from it and—sometimes—do something about it. Half of the value comes from just discovering that the information exists at all (e.g. noticing feelings that were always there and strong enough to influence your thoughts and behavior, but which were somewhat “under the radar” and subtle enough that they’d never actually caught your attention), and the other half comes from having new threads to pull on, new models to work with, and new theories to test.

The way this process works is by interfacing with your felt senses. The idea is that your brain doesn’t know how to drop all of its information directly into your verbal loop, so it instead falls back on influencing your physiology, and hoping that you notice (or simply respond). Butterflies in the stomach, the heat of embarrassment in your cheeks, a heavy sense of doom that makes your arms feel leaden and numb—each of these is a felt sense, and by doing a sort of gentle dialogue with your felt senses, you can uncover information and make progress that would be difficult or impossible if you tried to do it all “in your head.”

On the tip of your tongue

We’ll get more into the actual nuts and bolts of the technique in a minute, but first it’s worth emphasizing that Focusing is a receptive technique.

When Eugene Gendlin was first developing Focusing, he noticed that the patients who tended to make progress were making lots of uncertain noises during their sessions. They would hem and haw and hesitate and correct themselves and slowly iterate toward a statement they could actually endorse:

“I had a fight with my mother last week. Or—well—it wasn’t exactly a fight, I guess? I mean—ehhhhhhh—well, we were definitely shouting at the end, and I’m pretty sure she’s mad at me. It was about the dishes—or at least—well, it started about the dishes, but then it turned into—I think she feels like I don’t respect her, or something? Ugh, that’s not quite right, I’m pretty sure she knows I respect her. It’s like—hmmmmm—more like there are things she wants—she expects—she thinks I should do, just because—because of, I dunno, like tradition and filial piety, or something?”

Whereas patients who tended not to find value in therapy were those who already had a firm narrative with little room for uncertainty or perspective shift:

“Okay, so, I had another fight with my mother last week; she continues to make a lot of demands that are unreasonable and insists on pretending like she can decode my actions into some kind of hidden motive, like the dishes thing secretly means I don’t respect and appreciate everything she’s done for me. It’s frustrating, because that relationship is important to me, but she’s making it so that the only way I can maintain it is through actions I feel like I shouldn’t have to take.”

According to Gendlin, this effect was the dominant factor in patient outlook—more important than the type of therapy, or the magnitude of the problem, or the skill and experience of the therapist.

Gendlin posited that patients found value in this tip-of-the-tongue process because they were spending time at what he called “the edge”—the fuzzy boundary between implicit and explicit, between “already known” and “not yet known,” between pre-verbal and verbal. If (as is often the case for patients in therapy) one’s goal is increased awareness and clarity with regard to complex issues, spending time in the already-known areas is not very useful. The juicy stuff, the new insight and knowledge, comes from gently approaching that edge, being willing to sit with the vague and not-yet-clear, and patiently waiting as things materialize.

From the use-your-whole-brain perspective that CFAR tends to take, it makes sense that the latter patient—the one with a strong set of preconceptions—would be less likely to make progress than the former. The latter patient is using their System 2 explicit reasoning to make sense of the situation—and they’re using only their System 2. They have a top-down narrative explanation for everything that’s happening, and that top-down narrative is drowning out contrary evidence and subtle signals and anything that doesn’t fit the party line.

Whereas the former patient is certainly thinking, in the classic System 2 sense, but they’re also listening. They’re doing a sort of guess-and-check process, whereby they try out a label or a description, and then zero in on the note of discord. They’re allowing their implicit models to do a significant amount of the driving, and not settling on a single story prematurely.

There’s often a similar dynamic in Focusing, where people are trying to tease out the meaning of a felt sense that can be subtle or quiet or easily overwritten. The act of interfacing with a felt sense often feels like having something right on the tip of your tongue—you don’t know what it is, but you also know that you’ll recognize it once you get it. It’s like being at the grocery store without a list, and knowing that there’s something you’re forgetting, but not quite knowing what, and having to sort of gently feel your way toward it:

“Okay, what’s left, what’s left. Hmmm. I need … hmmm. It was for the party? Was it soda? No, it wasn’t—I mean yes, I do need soda, but that isn’t the thing I’m forgetting. Something for the snacks—was it … hummus? No, not hummus, but we’re getting clos—GUACAMOLE! Yes. That’s it. It was guacamole.”

From felt senses to handles

All right, so we have felt senses—which, to recap, are a sort of physiological reflection of some bit of information somewhere in your brain.

The next piece of the puzzle is handles.

A handle is like a title or an abstract for a felt sense. It’s a word, or short phrase, or story, or poem, or image—some System-2-parseable tag for the deeper thing that’s going on. It’s the True Name of the problem, in the magical sense used in fantasy novels—the True Name that gives you some degree of power over a thing.

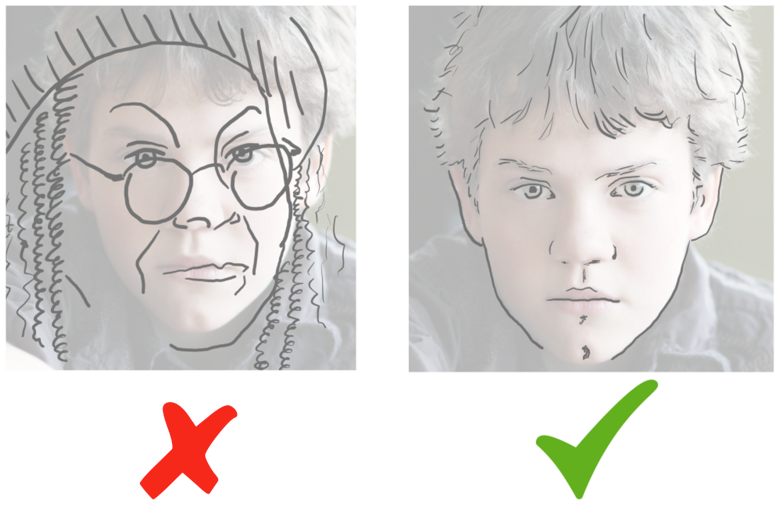

Let’s say a felt sense is like a photograph:

Photographs contain a lot of information. They’re rich in detail and nuance. They often have lots of colors and contrast. They’re unique, in the sense that it’s not at all hard to tell most photos apart from one another.

But the vast majority of that information is tacit. It’s hard to compress into words. If I were to show you a hundred similar photographs of a hundred similar faces, it would be pretty hard to get you to pick out the right one simply by talking about the details of the face.

The same is true of felt senses—or, more strictly, of the implicit mental models that lie behind the felt sense. The thing-in-your-thoughts that is producing the butterflies in your stomach, or the sudden tension in your shoulders, is built up of hundreds of tiny, interconnected thoughts and experiences and predictions that are very hard to sum up in words.

A sketch, on the other hand, is compressed. It can be evocative, but it’s sparse and utilitarian, conveying as much of the relevant information as possible with economy of line. In order to get something as rich as a real face out of a sketch, your brain has to do a lot of processing, and regenerate a lot of information, filling in a lot of gaps.

Yet a sketch can nevertheless be more or less accurate. It can be a good fit for the photograph—a true match. You could have a sketch of very high quality that just isn’t the same face:

It’s that sense of correspondence that we’re looking for, when we do Focusing. Gendlin often uses the word resonance—does the word or phrase that you just used resonate with the felt sense? Are they a good match for each other?

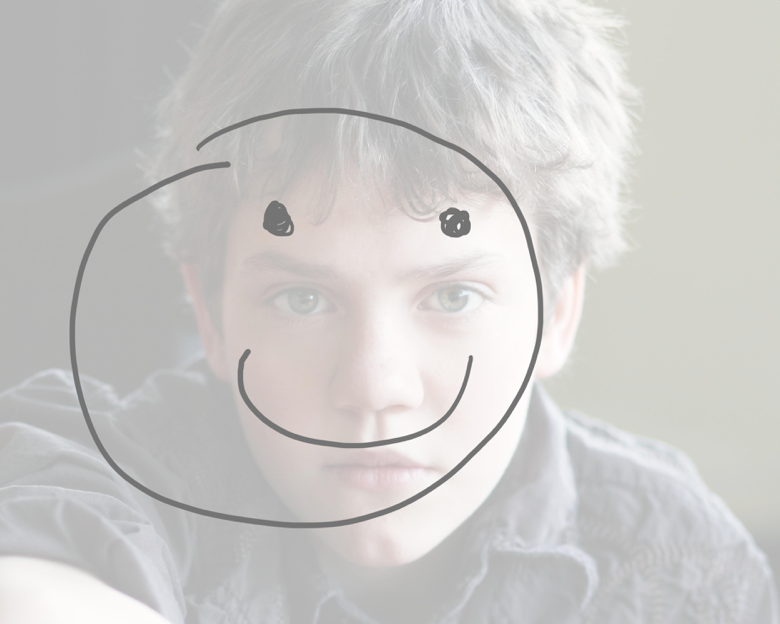

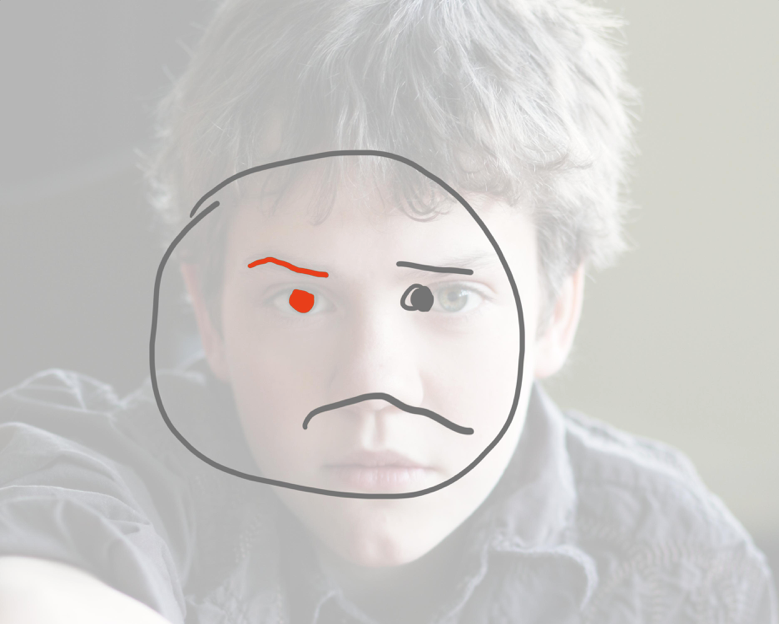

Often, your first attempt at a handle will not resonate at all. Let’s imagine that you’re focusing on something that’s been bothering you about your relationship with your romantic partner, and this has manifested itself in a felt sense of hot, slightly nauseous tightness in your chest.

You might try out a first-draft statement like “I’m bothered by the fact that we’ve been fighting a lot,” and then sort of hold that statement up against the felt sense, just like holding a sketch up next to a photograph to see if they match. You’ll think of the sentence, and then turn your attention back to the tightness in your chest, and see if the tightness responds in any way.

“No, that’s not it.”

From there, you can iterate and explore, following your sense of that was partially true—which part was most true?

“It’s more like—ugh—like I never know what to say? Or—no—it’s like I have to say the right things, or else.”

Hopefully, some part of the handle is more resonant with the felt sense, now that you’ve wiggled your way around a little—some part of it is a better match than before. And then you keep iterating, being sure to pause each time and leave space for the felt sense to respond. Remember, the goal is to listen, not to explain.

“It’s like—if I say the wrong thing, everything will fall apart? Because— because I’m the only one who’s trying to fix things, or something? Yeah—it’s like I’m the only one who’s willing to do the work—who’s willing to make sacrifices to keep the relationship healthy and strong.”

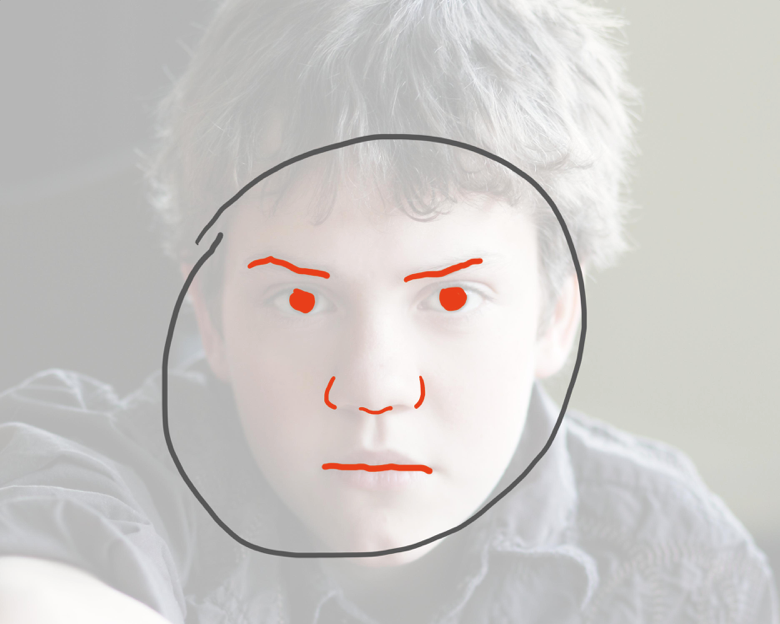

You get the idea. As the process continues, the handle grows more and more accurate, and evokes more and more of the underlying what’s-really-going-on. You’ll often feel a sort of click, or a release of pressure, or a deep rightness, once you say the thing that really completes the picture.

(Note that “completes” is actually a bit of an overstatement—it’s often the case that you don’t get a full picture of something like an entire face, but that instead you get a lot of clarity on one or more parts. In our metaphor, this would be something like, you traced the jawline and one eyebrow and nothing else, but you really got an accurate sense of that jawline and that eyebrow, and that produces a click on its own.)

Gendlin makes the point that the felt sense will often change—or vanish—once you’ve uncovered a good handle. It’s as if there was a part of you that was trying to send up a red flag via a physiological sensation—as long as your System 2 hasn’t got the message yet, that sensation is going to continue to occur. Once the message is accurately received, though, and your System 2 can write a poem that captures what that part of you was really trying to say, there’s often a relaxing, opening-up sort of feeling. The physiological alert is no longer necessary, because the problem is no longer unrecognized or unacknowledged or unclear.

Advice and caveats

Of course, the fact that you’ve accurately expressed your brain’s sense of what’s going on doesn’t mean you’ve found the bona-fide truth. As pretty much all of the rest of this handbook shows, we often have confused or incomplete or biased beliefs about the world around us and our own role within it.

But either way, getting clarity on what’s going on in your head, under the hood—on what sorts of narratives and frames resonate with the part of your subconscious that was generating frustration or fear or unease or pain in the first place—is usually a huge step forward in turning the problem into something tractable. Instead of being Something That’s Been Bothering Me, it’s now mundane, with gears and levers and threads to pull on. That’s not saying it’ll be easy to fix, just that it’s usually much better than fumbling around in the dark.

Here are some tips to keep in mind when practicing Focusing:

Choosing a topic

Often you’ll enter a Focusing session with a clear sense of what the session will be about—it’s the thing that’s been bothering you lately, or the thing that you can’t get out of your shower thoughts, or the thing that you haven’t got around to processing (but now’s the time).

If not, though, or if multiple things are all sort of clamoring for attention, one useful motion is to do something like laying them all out on the shelf.

Imagine saying, out loud, “Everything in my life is perfect right now.”

(You can also actually do this; it is often a useful exercise.)

For most people, there will usually be an immediate objection of some kind. Often there is both a word or phrase (the parking tickets!) and a visceral feeling (lump in my throat).

You can sort of imagine mentally lifting out the parking ticket problem and placing it on a shelf. Now the sentence becomes “Yeah, okay—so there’s that thing with the parking tickets, but other than that, everything in my life is perfect right now.”

<flinch>

“Oh, right, there’s that thing where I was going to already have an exercise routine by now, but I haven’t even started. Okay. So that’s there. But except for the parking tickets thing, and the exercise thing, everything in my life is perfect.”

...and so on.

Eventually, you should be able to say a sentence that feels true, and which doesn’t provoke any strong internal reaction—you should feel sort of calm and flat and level as you say it.

And then, from among the items “on the shelf,” you can choose one that you want to Focus with. Perhaps one of them seems particularly urgent or alive, or perhaps you’ll simply pick.

Or maybe, having gotten out all the tangible problems, there remains some sensation that you have no explanation for. Having created space for it, you can now sit with it and see what it has to say.

Get physically comfortable

The Focusing technique depends on you being able to attend to your physiological sensations, and also to do so with some degree of lightness. If you’re physically uncomfortable, you’re likely to end up either distracted (by e.g. a pain in your back) or with too much weight on your felt sense, as you brute-force your attention into place.

Don’t “focus”

The Focusing technique doesn’t mean focusing in the sense of “target your attention deliberately and with a lot of effort,” as in “stop daydreaming and focus!” Instead, it means something more like turning the knob on a microscope or a pair of binoculars—there’s something that you can see or sense, but only indistinctly, and the mental motion is one of gently bringing it into focus.

Hold space

Remember, Focusing is a receptive technique. Often, the back-and-forth between felt sense and handle will contain long stretches of silence—sometimes thirty seconds or more. Don’t push to go super fast, and don’t expect immediate clarity or staggering revelations. Just listen, and feel, and try to hold space for whatever might float up.

It’s worth noting here that we have a line in our Focusing class where we tell first-time participants “whatever it is you’re doing, that’s Focusing— don’t spend half your attention worrying about whether you’re doing the technique correctly. If you’re sitting and thinking and listening, you’re on the right track, and you can worry about the details later.”

Stay on one thread at a time

Often, during a Focusing session, other entangled threads will rise in relevance, and other felt senses will appear. While it’s good to let your attention shift, if there’s some new thing that feels more alive and worth listening to, it’s not good to let your attention split. We recommend a mental motion that’s something like asking the other felt senses to “wait out in the hallway”—acknowledge them, and perhaps form an intention to look into them later, but then return your attention to the thing you want to be Focusing on. It’s hard enough to “hear” what a single felt sense has to say; listening to two or three or four at once is not recommended.

Always return to the felt sense

It’s often easy, when Focusing, to start piecing things together in words, and to get excited about the story that’s cohering, and to end up “in your head.” If you notice this happening, pause, take a breath, and return back to the level of sensation—are you feeling anything in your body? What is it/what’s it like? Is it different from what you were feeling before? What does the felt sense “think” about the words you were just stringing together? What does the felt sense have to “say”?

Don’t limit yourself to the body

For many people, the idea of listening to and gathering information from their bodies is revelatory and revolutionary. But it’s important to note that there are whole other families of felt senses which CFAR participants have reported finding, and finding useful. For instance, rather than a physiological sensation, you might have a vivid image, or a sense of objects or feelings floating around your head, or just behind you. It’s important to check in the body, but don’t limit yourself to physiological felt senses—if you’re picking up on something else and finding it valuable, keep it up!

Try saying things out loud

This is useful both when trying to evoke felt senses (as when you say something you know is slightly false, so as to get a sense of the difference) and also can be useful in dialogue with your felt senses. Sometimes, phrases like “and what do I feel about that?” or “and what does that mean?” spoken aloud can shake something loose in a productive fashion.

Don’t get in over your head

This one is important. Frequently, first-time Focusers will dive right into a large and frightening felt sense, or get very very close to something deep and traumatic and personal. This can have the opposite of the intended effect, leaving you triggered or jittery or anxious. It can bring up a lot of stuff that you were sort of holding at arms’ length for good reason.

In cases like this, you can end up subject to the emotions and your experience of whatever’s going on, rather than being able to take them as object. They can fill your vision and be somewhat overwhelming.

The first piece of advice in this domain is “give yourself permission to not dive in too deep.” Simply reminding yourself that there are boundaries, and that you’re not required to climb down into the pit of despair, is often enough.

If you do find yourself drawn toward something large and scary, though, or if you find yourself slipping in despite your best efforts, we recommend doing something like going meta.

Let’s say you were in the middle of Focusing, and your current felt sense has a handle like “slumped and defeated.” You haven’t yet figured out what the slumped and defeated is about, and you were just about to start asking.

But you’re worried that might be too intense. What you can do instead is ask yourself how you feel about your sense that you feel slumped and defeated. When you hold that story in your mind, what’s your reaction to it? What does it feel like, to look at yourself and see “slumped and defeated”?

Perhaps your reaction to that is “sad.” You don’t like being in a slumped and defeated state, and so noticing that you are produces sadness.

If you check how you feel about that—if you ask yourself “what’s it like to feel sad about feeling slumped?”—you may find something like squidginess or uncertainty. You may be unsure whether it’s good or bad to feel sad about feeling slumped.

And if you check how you feel about the squidginess, you may finally reach a state of something like neutrality or equanimity or okay-ness. It seems “fine” to feel uncertain about feeling sad about feeling slumped. The loop has sort of bottomed out, and from that perspective you can see all of the things without being subject to any of them. You’re no longer blended with the parts of you that are in thrall to the emotion; you’re now outside of them, or larger than them, and able to dialogue with them, and that’s a good place from which to do Focusing.

Another way to create space in a similarly useful fashion is to simply restate a feeling two or three times, with increasing awareness and metacognitive distance each time. So, for instance, the word “rage” might become “I’m feeling rage,” and then “something in me is feeling rage,” and then “I’m sensing that something in me is feeling rage.” The slow backing-out from this is me to this is something I’m noticing can go a long way toward allowing you to engage with deep or heavy feelings without getting lost in them or overwhelmed by them.

The Focusing algorithm

1. Select something to bring into focus

Something that’s alive for you, or that has been looming in the back of your mind

Something that you haven’t had time for, but want to disentangle

Something where it seems like there’s insight on the tip of your tongue

Put your present worries on the shelf and see what else arises in the space you cleared.

2. Create space

Get into a physically comfortable position and spend a minute or two “dropping in.”

Put your attention into your body, and notice what sensations are present. If none are immediately obvious, start somewhere (e.g. the feet) and run your attention across your body part by part.

If you discover multiple things that are tugging at your attention, ask some of them to “wait in the hallway.”

If you are highly emotional or triggered or tense or overwhelmed, try going meta to slowly gain more space.

3. Look for a handle for your felt sense

Start with your best guess as to what’s going on, or what the feeling is about.

Remember to listen rather than projecting or explaining.

Continue returning to the level of sensation—what do you feel in your body?

Check for resonance each time you iterate. What does the felt sense “think” of the handle you just tried? What does it want to “say” in response?

Use prompts like “and now I’m feeling ” or “what this feels like in my body is .” Ask gentle questions like “and what’s that like?” or “how does it feel to say ?” or “and the thing about that is …”

Take your time, often as much as thirty or sixty or ninety seconds between sentences.

- Skills from a year of Purposeful Rationality Practice by (18 Sep 2024 2:05 UTC; 199 points)

- Advice for newly busy people by (11 May 2023 16:46 UTC; 150 points)

- How To Observe Abstract Objects by (30 Sep 2022 2:11 UTC; 54 points)

- Internal communication framework by (15 Nov 2022 12:41 UTC; 38 points)

- Advice for newly busy people by (EA Forum; 12 May 2023 23:47 UTC; 27 points)

- 's comment on sam’s Shortform by (30 Apr 2025 9:24 UTC; 18 points)

- Does the “ancient wisdom” argument have any validity? If a particular teaching or tradition is old, to what extent does this make it more trustworthy? by (4 Nov 2024 15:20 UTC; 18 points)

- 's comment on Opinionated Takes on Meetups Organizing by (25 Dec 2025 7:55 UTC; 15 points)

- LessWrong Meetup—Gendlin’s Focusing by (19 Jul 2022 16:55 UTC; 10 points)

- 's comment on Frame Bridging v0.8 - an inquiry and a technique by (20 Jun 2023 20:49 UTC; 8 points)

- 's comment on Johannes C. Mayer’s Shortform by (7 Oct 2023 2:33 UTC; 7 points)

- 's comment on How To Observe Abstract Objects by (15 Jan 2024 0:43 UTC; 6 points)

- Focusing by (24 Sep 2024 22:05 UTC; 5 points)

- Day Retreat Amsterdam: Resolving Internal Conflict by (EA Forum; 29 Mar 2024 8:49 UTC; 2 points)

- 's comment on Internal Double Crux by (8 Feb 2023 19:15 UTC; 2 points)

One trick helpful to me: Do this in your native language. Many aren’t native English speakers, but because so much they read about emotional growth and many of their “emotional growth conversations” are in English (bc most EA/LW meetups are in English, even e.g. here in Germany), it can be tempting to do Focusing in English as well. In my experience, this is a mistake.

Apart from any comment about the usefulness of this stuff, I just want to point out how patently ridiculous it is to name this very, very specific psychological technique “Focusing”. It’s akin to calling a particular 9-step yoga pranayama technique “Breathing”, or a particular diet “The Food Diet”. This usage “Focusing” clashes both with the common understanding of the word and with the more established, specific meditative meaning. It also doesn’t help that normal, everyday focusing is also something that you’d like to talk about in a psychology setting, so the context doesn’t uniquely rule out the other meanings of the word. I’m reminded of Jack Willis, who called his specific brand of Reichian Therapy “The Work”, perhaps in an attempt to make it seem more universal and important than it really was.

Yeah, definitely not the name we would have chosen if we’d been naming the technique (we were somewhat stuck with Eugene Gendlin’s choice).

I do think calling it “Gendlin’s Focusing” is probably a bit better.

Ah, but then we’d be misrepresenting it as the full technique?

“Step four of Gendlin’s Focusing” :/ :/ :/

I like the name focusing—it creates the feeling of the technique being powerful (since it signals it’s strong enough it can use a non-most-frequent meaning of focus (i.e. to concentrate)). Or maybe I’m feeling it incorrectly—English isn’t my first language—but I do like it.

Since when are we bound to the original discoverer’s wishes about naming?

I’m quite in favor of choosing a better name. I’ll start by proposing a long name that I think captures the essence: “Iterated felt-sense introspection”? Then maybe one could drop the “iterated” part for brevity. Other thoughts?

What does “felt sense” mean in contrast to simply “sense”? It has never been clear to me what work the word “felt” is doing there, other than making it a term of art that tells me that the writer is referencing Gendlin.

I believe that the “sense” in “felt sense” doesn’t mean “sense” as in “the five senses”, but rather “sense” as in “meaning”. So you could also say “felt meaning”. I think that contrasts with e.g. “cognitive meaning” (thoughts whose meaning we’re consciously aware of without needing to explicitly dig into them) and helps highlight that various things that we might describe as “feelings”, such as “a numb feeling in my back”, may actually contain meaning.

“I have a felt sense of danger in this situation” → “I have a sense/belief that this situation is dangerous, with that belief manifesting itself in the form of a feeling rather than explicit reasoning”

Yeah, it seems to me to point in the direction of “not necessarily legible but definitely there.” Intuitive, implicit, S1 instead of S2, similar to the distinction between aliefs and beliefs.

So… “alief”?

In many cases, a person doesn’t feel anything in their body for an alief. An alief is likely going to trigger a felt sense, but it’s useful to have different concepts for both to talk clearly.

I would not distinguish aliefs in the chest vs. aliefs in the abdomen but those categories make sense for felt senses.

That seems right to me.

Huh, pretty surprised that you agreed readily to that – I think the connotations of alief and felt sense are pretty different. (I think of “aliefs” as still fairly “propositional”, i.e. “I don’t belief my dad hates me, but apparently I alieve it.” Where felt senses include things that are sort-of-propositional but also things that don’t really have a clearcut meaning at all. Looking at your own post on The Felt Sense where you introduce it with the difference between the steampunk and forest artwork, the difference I get looking at each of them is very subtle and pretty unlike a lot of other experiences I have. It felt more to me like a sense-in-terms of “5 senses” than “meaning.”)

Hmm, maybe I’m just so used to thinking in terms of felt senses that I interpret all aliefs as being felt senses? :) E.g. when I hear the word “alief”, I usually think of Scott Alexander’s haunted house story, as well as these examples from Wikipedia:

And all of these aliefs feel like they would have distinct felt senses associated with them, e.g. if you cry at a sad movie because one of the characters died or lost something important to them, you probably have some kind of a felt sense of loss. If you’re afraid or disgusted, you have felt senses corresponding to both the general emotion as well as the more specific anticipation. It feels a little hard for me to imagine an alief that wouldn’t have a felt sense associated with it.

Though you could argue that while an alief implies a felt sense, a felt sense doesn’t necessarily imply an alief, and that steampunk vs. forest pictures differ in their felt senses but not their aliefs. I guess that depends on how exactly we’re defining an alief. I’m thinking of it as something like “a belief embedded in an implicit predictive model of the world”.

In that frame, the felt senses evoked by different kinds of pictures reflect unconscious beliefs about what kinds of things are associated with the specific things in the pictures E.g. there was relatively little specifically Victorian in the steampunk pictures, but that was a word that popped to my mind anyway when trying to describe the vibe in them, because of the more general steampunk <-> Victorian association. Aesthetics such as “steampunk” also seem to encode more complicated belief networks and predictions, as you’ve argued yourself. :)

There’s also the consideration that aliefs seem to activate not just beliefs, but also behavioral dispositions. E.g. if you’re standing on a transparent balcony or spending the night in a mansion that’s supposedly haunted, your aliefs may activate flight-type responses. (That was the most top-voted response to Scott’s haunted mansion post: that it’s less about there being a secret belief about the mansion really being haunted, and more about the mind being semi-hardwired to activate fear responses when you’re alone at night in an unfamiliar place with lots of weird sounds.) I think some of the more subtler changes you’re referencing to are something like changing activation levels in subsystems responsible for behavioral dispositions. E.g. looking from the steampunk pictures to the forest ones may cause the predominant input to be registered as “more safe”, which slightly downgrades the priority of systems with an objective of making yourself small in order to hide from threats, which may be subjectively experienced as a subtle sense of the mind opening up. And I think of those kinds of changes in behavioral dispositions as being driven by predictions (e.g. an environment being safe vs. unsafe) made on an alief level.

Okay, I guess the issue was I never actually had a clear definition of alief. But usually when I hear some say alief it’s in the context of ‘I alieve X’, where x is something propositional.

“Alief and Belief” (Gendler 2007) [PDF]

i mean in a pretty straightforward way… there are many senses (canonically but inaccurately, 5), and felt sense narrows the scope to “things you can feel in your body.” (I think it’s also intended to have more specific connotations, and just being clear that it’s a term of art is kinda useful)

FYI I think this post by Kaj Sotala is a good reference: https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/eccTPEonRe4BAvNpD/the-felt-sense-what-why-and-how

Also this other post (also by Duncan) has a somewhat different take on it (I think I might actually still find this post better than the OP) https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/PXqQhYEdbdAYCp88m/focusing-for-skeptics

There are different things you can sense.

You can sense your breathing movement inside of your body but it’s not a felt sense. With training, you can feel your heartbeat but it’s also not a felt sense. You can also sense temperature in your body.

Gendlin used a new term to distinguish a certain class of feelings and it’s useful to have a combination of two words, to refer to it, that is not used in other contexts.

If you would speak to yoga people who are good at categorization, they would likely speak about a sense of something on a different Kosha (/sheath) than the one where you feel the breathing movement. Saying “felt sense” is a simple way to go one step in the direction of making a new distinction without importing a system with a bunch of strange history like the Yoga one.

“felt” also has the nice property of it describing the relationship of how the person relates to the sense and that relationship matters for the process to work.

A physical sensation entangled with an interpretation.

This reminds me a lot of what I would do when I was trying to access the Spirit of God to get divine guidance, back when I was Mormon. The essential distinction is in your sentence:

In the process of getting my mind untied from my Mormon upbringing, I became a lot more connected with my rational mind and more untrusting of my subconscious. This is a good reminder that you have to pay attention to that subconscious processing when it comes to understanding what’s happening in your head.

Edit: I’d like to add a point that another exmormon friend made to me:

In my experience, it is not safe to rely on this sort of subconscious exploration when you have been taught to have a strong fear of certain “unsafe” or “sinful” thoughts. It brings you too close to emotional reasoning.

In the PDF version of the handbook, this section recommends these further resources on focusing:

Summary

Focusing is a technique for bringing subconscious system 1 information into conscious awareness

Felt sense: a feeling in the body that is not yet verbalized but may subconsciously influence behavior, and which carries meaning.

The dominant factor in patient outcomes: does the patient remain uncertain, instead of having firm narratives?

A goal of therapy is increased awareness and clarity. Thus, it is not useful to spend much time in the already known.

The successful patient thinks and listens to information

If the verbal part utters something, the patient will check with the felt senses to correct the utterance

Listening can feel like “having something on the tip of your tongue”

From felt senses to handles

A felt sense is like a picture

There’s lots of tacit, non-explicit information in it

A handle is like a sketch of the picture that is true to it.

Handles “resonate” with the felt sense

The first attempt at a handle will often not resonate — then you need to iterate

In the end, you might get a “click”, “release of pressure”, or “sense of deep rightness”

The felt sense can change or disappear once “System 2 got the message”

Advice and caveats

The felt sense may also not be true — your system 1 may be biased.

Tips:

Choosing a topic: if you don’t have a felt sense to focus on, produce the utterance “Everything in my life is perfect right now” and see how system 1 responds. This will usually create a topic to focus on

Get physically comfortable

Don’t “focus” in the sense of effortful attention, but “focus” in the sense of “increase clarity”

Hold space: don’t go super fast or “push”; silence in one’s mind is normal

Stay with one felt sense at a time

Always return to the felt sense, also if the coherent verbalized story feels “exciting”

Don’t limit yourself to sensations in your body — there are other felt senses

Try saying things out loud (both utterances and questions “to the felt sense”)

Try to not “fall into” overwhelming felt senses; they can sometimes make the feeling a “subject” instead of an “object” to hold and talk with

Going “meta” and asking what the body has to say about a felt sense can help with not getting sucked in

Verbalizing “I feel rage” and then “something in me is feeling rage” etc. can progressively create distance to felt senses

The Focusing Algorithm

Select something to bring into focus

Create space (get physically comfortable and drop in for a minute; Put attention to the body; ask sensations to wait if there are multiple; go meta if you’re overwhelmed)

Look for a handle of the felt sense (Iterate between verbalizing and listening until the felt sense agrees; Ask questions to the felt sense; Take time to wait for responses)

I couldn’t think about this before, ’cause it was obviously false in 100% of cases. I’ve gained greater understanding now.

“Perfect” is a 3-place word. It asks if a given state of the world is the best of a given set of states, given some values.

Is perfect(my life right now, ???, my values) true? If we take the minimal set as default, we get perfect(my life right now, my life right now, my values), which is obviously true. This isn’t totally unreasonable; there’s only one multiverse in the world, and there’s only one set of things in it I identify with. It’s very.intuitive to just stop there.

The sentence on its own doesn’t feel much false or true. But it doesn’t feel inconceivable anymore either.

I feel like I’ve come to the insight backward. I’ll keep meditating, haha.