Optimal Timing for Superintelligence: Mundane Considerations for Existing People

[Sorry about the lengthiness of this post. I recommend not fixating too much on all the specific numbers and the formal apparatus. Originally the plan was to also analyze optimal timing from an impersonal (xrisk-minimization) perspective; but to prevent the text from ballooning even more, that topic was set aside for future work (which might never get done). But I should at least emphasize that there are other important factors, not covered here, that would need to be taken into account if one wishes to determine which timeline would be best all things considered.]

[Working paper.[1] Version 1.0. Canonical link to future revised version of this paper.]

Abstract

Developing superintelligence is not like playing Russian roulette; it is more like undergoing risky surgery for a condition that will otherwise prove fatal. We examine optimal timing from a person-affecting stance (and set aside simulation hypotheses and other arcane considerations). Models incorporating safety progress, temporal discounting, quality-of-life differentials, and concave QALY utilities suggest that even high catastrophe probabilities are often worth accepting. Prioritarian weighting further shortens timelines. For many parameter settings, the optimal strategy would involve moving quickly to AGI capability, then pausing briefly before full deployment: swift to harbor, slow to berth. But poorly implemented pauses could do more harm than good.

Introduction

Some have called for a pause or permanent halt to AI development, on grounds that it would otherwise lead to AGI and superintelligence, which would pose intolerable dangers, including existential risks. For instance, Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares argue in their recent book If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies that nations should enforce a global ban on advanced AI and the computational infrastructure to support it, and on research into improved AI algorithms.[2] These authors are extremely pessimistic about the prospects of aligned superintelligent AI, regarding its advent as an almost certain doom. In their view, creating superintelligence would be far worse than subjecting all of humanity to a universal death sentence.[3] Others have argued that even a much lower level of risk would warrant an indefinite moratorium on AI. Would it not be wildly irresponsible, they ask, to expose our entire species to even a 1-in-10 chance of annihilation?

However, sound policy analysis must weigh potential benefits alongside the risks of any emerging technology. Yudkowsky and Soares maintain that if anyone builds AGI, everyone dies. One could equally maintain that if nobody builds it, everyone dies. In fact, most people are already dead. The rest of us are on course to follow within a few short decades. For many individuals—such as the elderly and the gravely ill—the end is much closer. Part of the promise of superintelligence is that it might fundamentally change this condition.

For AGI and superintelligence (we refrain from imposing precise definitions of these terms, as the considerations in this paper don’t depend on exactly how the distinction is drawn), the potential benefits are immense. In particular, sufficiently advanced AI could remove or reduce many other risks to our survival, both as individuals and as a civilization.

Superintelligence would be able to enormously accelerate advances in biology and medicine—devising cures for all diseases and developing powerful anti-aging and rejuvenation therapies to restore the weak and sick to full youthful vigor.[4] (There are more radical possibilities beyond this, such as mind uploading, though our argument doesn’t require entertaining those.[5]) Imagine curing Alzheimer’s disease by regrowing the lost neurons in the patient’s brain. Imagine treating cancer with targeted therapies that eliminate every tumor cell but cause none of the horrible side effects of today’s chemotherapy. Imagine restoring ailing joints and clogged arteries to a pristine youthful condition. These scenarios become realistic and imminent with superintelligence guiding our science.

Aligned superintelligence could also do much to enhance humanity’s collective safety against global threats. It could advise us on the likely consequences of world-scale decisions, help coordinate efforts to avoid war, counter new bioweapons or other emerging dangers, and generally steer or stabilize various dynamics that might otherwise derail our future.

In short, if the transition to the era of superintelligence goes well, there is tremendous upside both for saving the lives of currently existing individuals and for safeguarding the long-term survival and flourishing of Earth-originating intelligent life. The choice before us, therefore, is not between a risk-free baseline and a risky AI venture. It is between different risky trajectories, each exposing us to a different set of hazards. Along one path (forgoing superintelligence), 170,000 people die every day of disease, aging, and other tragedies; there is widespread suffering among humans and animals; and we are exposed to some level of ongoing existential risk that looks set to increase (with the emergence of powerful technologies other than AI). The other path (developing superintelligence) introduces unprecedented risks from AI itself, including the possibility of catastrophic misalignment and other failure modes; but it also offers a chance to eliminate or greatly mitigate the baseline threats and misfortunes, and unlock wonderful new levels of flourishing. To decide wisely between these paths, we must compare their complex risk profiles—along with potential upsides—for each of us alive today, and for humanity as a whole.

With this in mind, it becomes clear (pace Hunt, Yampolskiy, and various other writers) that analogies likening AGI development to a game of Russian roulette are misplaced.[6] Yes, launching superintelligence entails substantial risk—but a better analogy is a patient with severe heart disease deciding whether to undergo risky surgery. Imagine a patient with advanced coronary artery disease who must weigh the immediate risk of bypass surgery against the ongoing risk of leaving the condition untreated. Without an operation, they might expect to live for several more months, with a gradually increasing daily risk of a fatal cardiac event. The risk of dying on any given day remains small, but it relentlessly accumulates over time. If they opt for surgery, they face a much higher risk of dying immediately on the operating table. However, if the procedure succeeds, the reward is many additional years of life in better health.

Whether the patient should undergo the operation, and if so when, depends on many variables—their tolerance for risk, their discount rate on future life years, whether a more skillful surgeon is likely to become available at some point, how much better their quality of life would be if the condition is cured, and so on. All these considerations have clear parallels in deciding whether and when to deploy transformative superintelligent AI.[7]

When we take both sides of the ledger into account, it becomes plausible that our individual life expectancy is higher if superintelligence is developed reasonably soon. Moreover, the life we stand to gain would plausibly be of immensely higher quality than the life we risk forfeiting. This conclusion holds even on highly pessimistic “doomer” assumptions about the probability of misaligned AI causing disaster.

Evaluative framework

To analyze all the facets of our predicament is possibly infeasible—certainly too complex to attempt in a single paper. However, we can examine some of the tradeoffs through a few different lenses, each providing a view on some of the relevant considerations. By breaking the issue down in this way, we can clarify some aspects of the macrostrategic choices we face, even if a comprehensive evaluation remains out of reach.

One distinction that may usefully be made is between what we could term mundane and arcane realms of consideration. By the former we refer to the ordinary kinds of secular considerations that most educated modern people would understand and not regard as outlandish or weird (given the postulated technological advances). The latter refers to all the rest—anthropics, simulation theory, aliens, trade between superintelligences, theology, noncausal decision theories, digital minds with moral status, infinite ethics, and whatnot. The arcane is, in the author’s view, relevant and important; but it is harder to get to grips with, and rolling it in upfront would obscure some simpler points that are worth making. In this paper, we therefore limit our purview to mundane considerations (leaving more exotic issues to possibly be addressed in subsequent work).[8]

Within either the mundane or arcane domain, we must also decide which evaluative standard to apply. In particular, we may distinguish between a person-affecting perspective, which focuses on the interests of existing people, and an impersonal perspective, which extends consideration to all possible future generations that may or may not come into existence depending on our choices. Individual mortality risks are salient in the person-affecting perspective, whereas existential risks emerge as a central concern in the impersonal perspective. In what follows, we adopt the person-affecting perspective (leaving an analysis from the impersonal perspective for future work).

We begin by introducing a very simple model. Subsequent sections will explore various complications and elaborations.[9]

A simple go/no-go model

Suppose that without superintelligence, the average remaining life expectancy is 40 years.[10] With superintelligence, we assume that rejuvenation medicine could reduce mortality rates to a constant level similar to that currently enjoyed by healthy 20-year-olds in developed countries, which corresponds to a life expectancy of around 1,400 years.[11] This is conservative, since superintelligence could also mitigate many non-aging causes of death—such as infectious diseases, accidents, and suicidal depression. It is also conservative because it ignores more radical possibilities (like mind uploading with periodic backup copies), which could yield vastly longer lifespans.[12]

Now consider a choice between never launching superintelligence or launching it immediately, where the latter carries an % risk of immediate universal death. Developing superintelligence increases our life expectancy if and only if:

In other words, under these conservative assumptions, developing superintelligence increases our remaining life expectancy provided that the probability of AI-induced annihilation is below 97%.

More generally, let m0 be the annual mortality hazard before AGI, and let m1 be the hazard after a successful AGI launch. Assign positive quality-of-life weights q0 and q1 to life before and after AGI, respectively. Launching immediately increases (quality-adjusted) life expectancy for those alive today iff:

Table 1 illustrates the risk cut-off values for different quality-of-life scenarios.

TABLE 1: Acceptable AI-risk if post-AGI life expectancy is 1,400 years

| Pre-AGI LE (y) | Post-AGI LE (y) | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | 1,400 | 1 | 97.1% |

| 40 | 1,400 | 2 | 98.6% |

| 40 | 1,400 | 10 | 99.7% |

Table 2 shows the corresponding thresholds if the gain in life expectancy were only 20 years (so post-AGI life expectancy is 60 years instead of 40)—perhaps a case in which the underlying aging processes for some reason remain unaddressed.

TABLE 2: Acceptable AI-risk if post-AGI life expectancy is 60 years

| Pre-AGI LE (y) | Post-AGI LE (y) | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | 60 | 1 | 33.3% |

| 40 | 60 | 2 | 66.7% |

| 40 | 60 | 10 | 93.3% |

We observe that, from a mundane person-affecting perspective—even without a difference in quality of life and with very modest assumptions about superintelligence-enabled life extension—developing superintelligence now would increase expected remaining lifespan even with fairly high levels of AI risk.[13]

Incorporating time and safety progress

The previous section treated the choice as binary: either launch superintelligence now or never launch it at all. In reality, however, we may instead face a timing decision. We may be able to make AGI safer by slowing its development or delaying its deployment, allowing further alignment research (and other precautions) to reduce the risk of catastrophic failure. This introduces a new tradeoff. Launching earlier means accepting a higher level of AI risk; launching later means extending the period during which people continue to die from ordinary causes and remain vulnerable to other background dangers.

This mirrors the medical analogy introduced earlier. A patient might postpone a risky operation in the hope that a safer method becomes available, but waiting exposes them to the ongoing risk of the underlying disease (and postpones their enjoying a state of improved health).

To formalize this idea (details in Appendix A), we assume that before AGI, individuals face a constant mortality hazard m0; after a successful launch, this drops to a much lower value m1. We also assume that the probability of catastrophic failure if AI is launched at time t declines gradually as safety work advances. The central question becomes: How long is it worth waiting for additional safety progress?

Table 3 shows representative “optimal waiting times” under different assumptions about the initial level of AGI risk and the (relative) rate at which that risk is reduced through further safety work. We include some perhaps unrealistically extreme values for initial (at ) and rate of safety progress to get a sense of the full space of possibilities.

TABLE 3: Optimal delay for various initial risks and rates of safety progress

| Safety Progress | 1% | 5% | 20% | 50% | 80% | 95% | 99% |

| No progress (0%/yr) | Launch asap | Launch asap | Launch asap | Launch asap | Launch asap | Launch asap | Never |

| Glacial (0.1%/yr) | Launch asap | Launch asap | Launch asap | Launch asap | Launch asap | Wait 16.9y | Wait 58.1y |

| Very slow (1%/yr) | Launch asap | Launch asap | Launch asap | Launch asap | Wait 14.3y | Wait 14.3y | Wait 35.5y |

| Moderate (10%/yr) | Launch asap | Launch asap | Wait 8.1m | Wait 9.4y | Wait 13.8y | Wait 15.5y | Wait 15.9y |

| Brisk (50%/yr) | Launch asap | Wait 6.8m | Wait 2.6y | Wait 3.9y | Wait 4.6y | Wait 4.8y | Wait 4.9y |

| Very fast (90%/yr) | Launch asap | Wait 8.2m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.7y | Wait 1.9y | Wait 2.0y | Wait 2.0y |

| Ultra-fast (99%/yr) | Wait 1.7m | Wait 5.9m | Wait 9.5m | Wait 11.9m | Wait 1.1y | Wait 1.1y | Wait 1.1y |

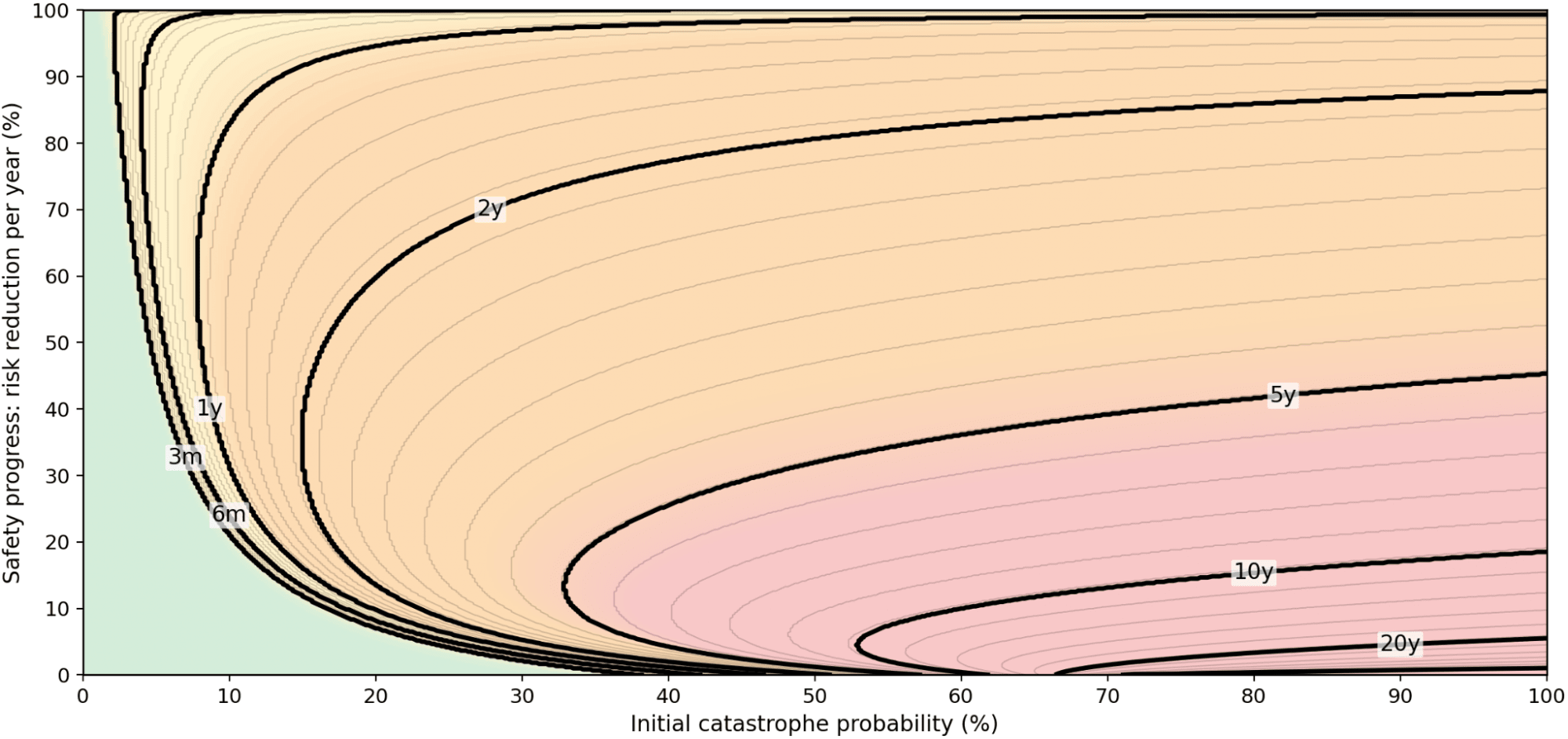

We observe a clear pattern. When the initial risk is low, the optimal strategy is to launch AGI as soon as possible—unless safety progress is exceptionally rapid, in which case a brief delay of a couple of months may be warranted. As the initial risk increases, optimal wait times become longer. But unless the starting risk is very high and safety progress is sluggish, the preferred delay remains modest—typically a single-digit number of years. The situation is further illustrated in Figure 1, which shows iso-delay contours across the parameter space.

Interestingly, both very fast and very slow rates of safety progress favor earlier launch. In the fast-progress case, the risk drops so quickly that there is no need to wait long. In the slow-progress case, waiting yields little benefit, so it is better to act sooner—while the potential gains are still reachable for many. It is intermediate-to-slow progress rates that produce the longest optimal delays: just slow enough that safety improvements accumulate only gradually, but fast enough that waiting still buys some benefit. (There is also a corner case: if the initial risk is extremely high and safety improvements are negligible or non-existent, the model recommends never launching at all.)

If we measured outcomes in quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) rather than raw life-years, we would in most cases become even more impatient to launch. However, in the current model, this effect is modest. The prospect of reducing mortality to that of a healthy 20-year-old already dominates the tradeoff, making the value of the short pre-AGI period relatively insignificant by comparison. What drives the result is the balance between the risk of dying before AGI arrives, and the risk of dying because the launch goes wrong.

FIGURE 1: Iso-delay contours (cf. Table 3)

Temporal discounting

Thus far, we have assumed that future life-years are valued equally regardless of when they occur. In practice, decision-makers often apply a temporal discount rate, which downweights benefits that occur further in the future. Various pragmatic factors that are sometimes baked into an economic discount rate can be set aside here. For example, we should not use the discount rate to account for the fact that we may prefer to frontload good things in our lives on the ground that we might not be around to enjoy them if they are postponed far into the future (since we are modeling mortality risks separately). But decision-makers are sometimes supposed to also have a “pure time preference”, where they simply care less about what happens further into the future, and this is what we will examine here.

Discounting weakens the incentive to “rush” for the vast long-term life extension that successful AGI might bring. The enormous benefit of gaining centuries of expected life is no longer valued at its full magnitude; whereas the risk of dying soon—either from a misaligned AGI or from current background hazards—remains at nearly full weight. As a result, introducing a discount rate shifts the optimal launch date later.

Table 4 illustrates the effect of a medium (3%) annual discount rate on optimal AGI timing. (Technical details appear in Appendix B, along with results for other discount rates.)

TABLE 4: Optimal delay with a 3% annual discount rate

| Safety Progress | 1% | 5% | 20% | 50% | 80% | 95% | 99% |

| No progress (0%/yr) | Launch asap | Launch asap | Launch asap | Never | Never | Never | Never |

| Glacial (0.1%/yr) | Launch asap | Launch asap | Launch asap | Wait 142.3y | Wait 612.0y | Wait 783.8y | Wait 825.0y |

| Very slow (1%/yr) | Launch asap | Launch asap | Launch asap | Wait 29.1y | Wait 75.8y | Wait 92.9y | Wait 97.0y |

| Moderate (10%/yr) | Launch asap | Launch asap | Wait 2.6y | Wait 11.3y | Wait 15.8y | Wait 17.4y | Wait 17.8y |

| Brisk (50%/yr) | Launch asap | Wait 7.5m | Wait 2.6y | Wait 3.9y | Wait 4.6y | Wait 4.9y | Wait 4.9y |

| Very fast (90%/yr) | Launch asap | Wait 8.2m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.7y | Wait 1.9y | Wait 2.0y | Wait 2.0y |

| Ultra-fast (99%/yr) | Wait 1.7m | Wait 5.9m | Wait 9.5m | Wait 11.9m | Wait 1.1y | Wait 1.1y | Wait 1.1y |

We see that some borderline cases shift from “launch immediately” to “wait a bit”; and cases that already warranted waiting now recommend longer delays. Higher discount rates would amplify this effect: if the far future counts for little, it makes sense to mostly focus on securing the near future.

Quality of life adjustment

One important hope is that developing superintelligence will not only extend life but also make it better. We can model this by assigning a quality weight to life before AGI and a higher weight to life after a successful AGI launch.

Table 5 shows optimal timing when post-AGI life is twice as good as current life () with a standard 3% discount rate. (See Appendix C for details and further illustrations.)

TABLE 5: Optimal delay: small quality difference (q₁/q₀ = 2, medium discount rate )

| Safety Progress | 1% | 5% | 20% | 50% | 80% | 95% | 99% |

| No progress (0%/yr) | Launch asap | Launch asap | Launch asap | Launch asap | Never | Never | Never |

| Glacial (0.1%/yr) | Launch asap | Launch asap | Launch asap | Launch asap | Wait 122.2y | Wait 294.0y | Wait 335.2y |

| Very slow (1%/yr) | Launch asap | Launch asap | Launch asap | Launch asap | Wait 27.1y | Wait 44.2y | Wait 48.3y |

| Moderate (10%/yr) | Launch asap | Launch asap | Launch asap | Wait 6.7y | Wait 11.1y | Wait 12.8y | Wait 13.2y |

| Brisk (50%/yr) | Launch asap | Launch asap | Wait 1.9y | Wait 3.2y | Wait 3.9y | Wait 4.2y | Wait 4.2y |

| Very fast (90%/yr) | Launch asap | Wait 5.7m | Wait 1.1y | Wait 1.5y | Wait 1.7y | Wait 1.8y | Wait 1.8y |

| Ultra-fast (99%/yr) | Wait 12.8d | Wait 4.6m | Wait 8.2m | Wait 10.6m | Wait 11.8m | Wait 1.0y | Wait 1.0y |

We can see that higher post-AGI quality expands the “launch asap” region, and shortens delays in the instances where waiting is optimal.

The magnitude of this shift is limited because the “launch-asap” risk bar—the level of AGI-risk below which it becomes optimal to launch immediately—is bounded above. This means that the quality-effect saturates: even arbitrarily large quality improvements cannot push all cases to immediate launch. Thus, if we postulated that post-AGI life would be 1,000 or 10,000 times better than pre-AGI life, this would not make much difference compared to more modest levels of quality improvement. Intuitively, once post-AGI life becomes sufficiently attractive (because of its length and/or quality), pre-AGI life contributes relatively little to the expected value of the future; and the chief concern then becomes maximizing the chance of actually reaching the post-AGI era—i.e. balancing the improvements in AGI safety that come from waiting against the accumulating risk of dying before AGI if the wait is too long.

Interestingly, the effect of temporal discounting can flip sign depending on the magnitude of the pre/post-AGI quality differential. When there is no quality differential, higher temporal discount rates always push towards launching later. However, when there is a quality differential that is sufficiently large, impatience penalizes delaying the onset of the higher-quality existence that would follow a successful superintelligence; and this pulls towards launching earlier. Consequently, while discounting always acts as a brake in the pure longevity model, it acts as an accelerator when the quality-of-life gap is sufficiently large.

Diminishing marginal utility

The preceding models have relied on a linear value assumption—essentially treating a 1,400-year lifespan as subjectively worth exactly 35 times as much as a 40-year lifespan. However, most people’s actual current preferences may exhibit diminishing marginal utility in quality-adjusted lifeyears (QALYs), meaning that e.g. a ten-year extension of a life that would otherwise be, say, 30 years is regarded as more desirable than a ten-year extension of a life that would otherwise be 1,390 years. Such a preference structure can also be viewed as a form of risk-aversion. Few people would accept a coin flip where “heads” means doubling their remaining lifespan and “tails” means dying immediately—and they may reject it even if we introduce a modest sweetener (such as a $10,000 reward or an additional bonus lifeyear if the coin lands heads).

We can model this using a standard diminishing-returns utility function—constant relative risk aversion (CRRA)—that introduces a curvature parameter, , representing the degree of risk-aversion. As this parameter increases, the decision-maker becomes more conservative, requiring higher probabilities of success (or greater potential upside) before betting their current life on a transformation.

Table 6 shows the results for , a typical value derived from the empirical health-economics literature. Other parameters are the same as in the previous section. (See Appendix D for details and additional illustrations.)

TABLE 6: Diminishing marginal utility (CRRA, medium rate)

| Safety Progress | 1% | 5% | 20% | 50% | 80% | 95% | 99% |

| No progress (0%/yr) | Launch asap | Launch asap | Launch asap | Launch asap | Never | Never | Never |

| Glacial (0.1%/yr) | Launch asap | Launch asap | Wait 3.1d | Wait 1.9y | Wait 122.6y | Wait 294.0y | Wait 335.2y |

| Very slow (1%/yr) | Launch asap | Launch asap | Wait 4.2d | Wait 4.4y | Wait 31.7y | Wait 46.3y | Wait 50.1y |

| Moderate (10%/yr) | Launch asap | Launch asap | Wait 1.1y | Wait 8.4y | Wait 12.5y | Wait 14.1y | Wait 14.4y |

| Brisk (50%/yr) | Launch asap | Wait 4.4m | Wait 2.3y | Wait 3.6y | Wait 4.2y | Wait 4.5y | Wait 4.5y |

| Very fast (90%/yr) | Launch asap | Wait 7.2m | Wait 1.2y | Wait 1.6y | Wait 1.8y | Wait 1.9y | Wait 1.9y |

| Ultra-fast (99%/yr) | Wait 1.2m | Wait 5.4m | Wait 9.0m | Wait 11.3m | Wait 1.0y | Wait 1.1y | Wait 1.1y |

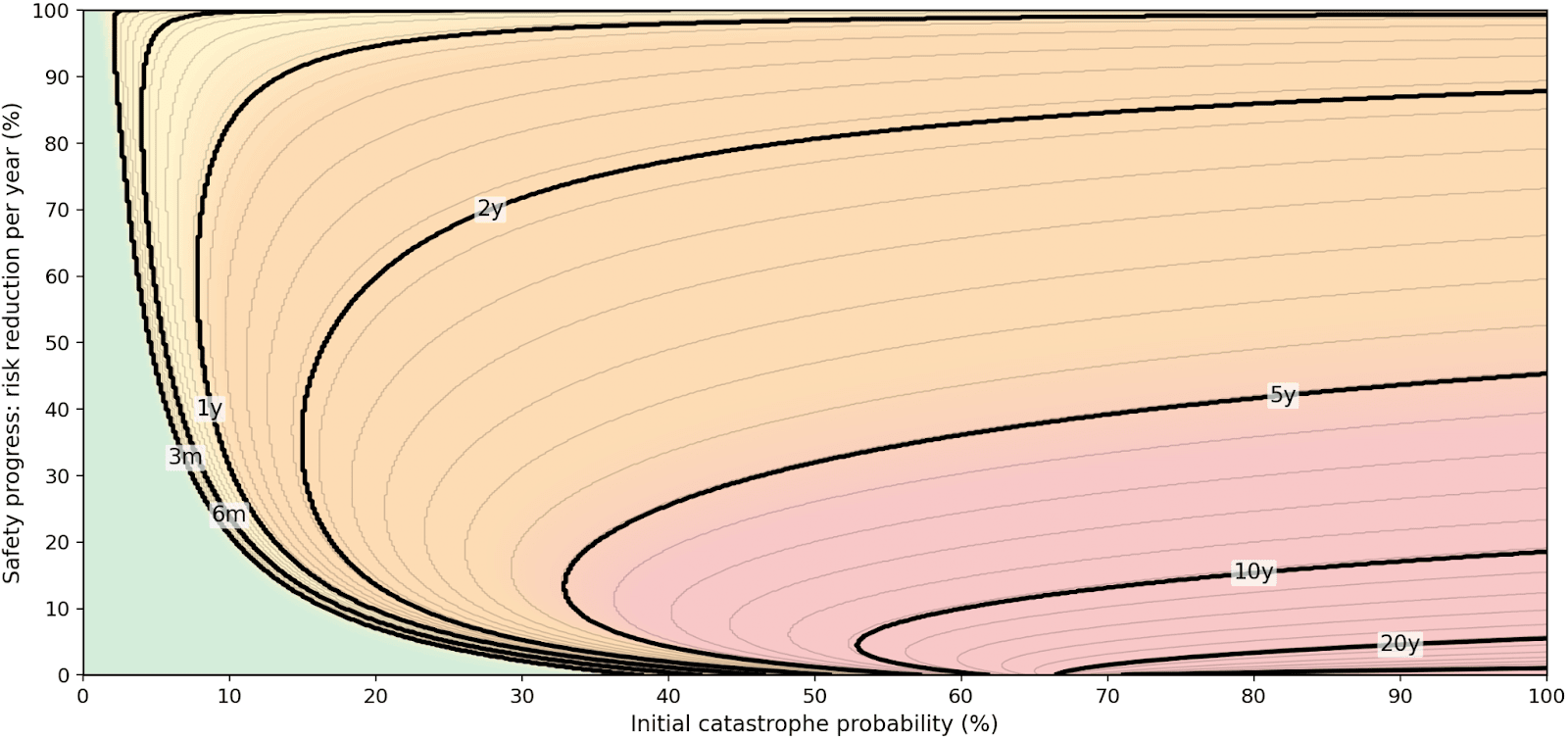

Comparing this to Table 5, we see that diminishing marginal utility in QALYs leads to a somewhat more conservative approach: the zone of “launch asap” shrinks and optimal wait times increase. This effect is strongest for earlier dates. (See also Figure 2.)

FIGURE 2: Iso-delay contours (cf. Table 6)

Table 7 shows what the risk is if launch occurs at the optimal time (for the same parameter settings as Table 6).

TABLE 7: Risk-at-launch (for the same model)

| Safety Progress | 1% | 5% | 20% | 50% | 80% | 95% | 99% |

| No progress (0%/yr) | 1.0% | 5.0% | 20.0% | 50.0% | Never | Never | Never |

| Glacial (0.1%/yr) | 1.0% | 5.0% | 20.0% | 49.9% | 70.8% | 70.8% | 70.8% |

| Very slow (1%/yr) | 1.0% | 5.0% | 20.0% | 47.9% | 58.1% | 59.6% | 59.9% |

| Moderate (10%/yr) | 1.0% | 5.0% | 17.9% | 20.6% | 21.4% | 21.6% | 21.6% |

| Brisk (50%/yr) | 1.0% | 3.9% | 4.1% | 4.2% | 4.2% | 4.2% | 4.2% |

| Very fast (90%/yr) | 1.0% | 1.3% | 1.3% | 1.3% | 1.3% | 1.3% | 1.3% |

| Ultra-fast (99%/yr) | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.6% |

These risk-at-launch values are somewhat—but not dramatically—reduced compared to those of a risk-neutral agent (except in cases where the risk-neutral agent would never launch or the risk-averse agent would launch asap, in which case risk-at-launch is the same for both).

Changing rates of safety progress

In the models considered so far, we assumed that AGI can be launched at any time, that background mortality remains constant until launch, that AI safety improves at a constant rate, and that no evidence about system safety is obtained beyond what that steady progress implies. In reality, however, we are not yet in a position to launch full AGI; background mortality risk could shift around the time AGI becomes available; the pace of safety progress is likely to vary across stages; and we may be able to run tests that provide direct information about whether a system is safe. We now explore how some of these factors affect the picture.

It is helpful to distinguish two timing variables:

: the time from now until full AGI first becomes technically deployable. We will refer to this period as Phase 1.

: any additional delay we choose after that point before deploying—a deliberate pause between AGI becoming available and being rolled out at scale. We will refer to such a period as Phase 2.

Launch thus occurs at time .

In principle, one could try to choose both variables so as to maximize expected (discounted, quality-adjusted) life-years. In practice, may be harder to affect to a degree that makes a significant difference. It is largely determined by the inherent technical difficulty of attaining AGI-level capabilities and by investment choices currently driven by intense competitive dynamics; whereas , in at least some scenarios, may be more a matter of deliberate choice by company leaders or policymakers who at that juncture may be more focused on making macrostrategically sound deployment decisions. Furthermore, as we shall see, relatively small changes to plausibly make a bigger difference to expected outcomes than similarly small changes to .

Before considering joint optimization over both variables, therefore, let us examine a model in which only is subject to choice. Here we treat as exogenous and given by the scenario (0, 5, 10, or 20 years until AGI availability). We retain the notation and parameters from previous sections, including exponential time discounting and concave utility (both at their “medium” values unless otherwise noted).

A key feature of this multiphase setup is that the rate of safety progress need not be constant. Different stages of development offer different opportunities for progress, and the most tractable problems tend to be solved first.

During Phase 1—the period before full AGI is available—safety researchers must work without access to the systems that will ultimately matter most. They can study precursor systems, develop theoretical frameworks, and devise alignment techniques that seem likely to scale; but the exact algorithms and architectures that enable full AGI remain unknown, limiting what can be tested or verified. Safety progress during this phase is therefore likely to be moderate.

The situation changes once AGI-ready systems are attained. In Phase 2, researchers can study the actual system, run it in constrained environments, probe its behavior under controlled conditions, and potentially leverage the system’s own capabilities to accelerate safety work. This suggests a burst of rapid safety progress immediately after AGI becomes available—a “safety windfall” from finally having the real artifact to work with.

Yet such rapid gains cannot continue indefinitely. The most promising interventions get explored first, and diminishing returns eventually set in. This motivates dividing Phase 2 into distinct subphases:

Phase 2a: An initial period of very rapid safety progress. With the full system now available, researchers can perform interventions that were previously impossible—shaping the system, probing failure modes while slowly ramping capabilities, and implementing oversight mechanisms on the actual weights. This subphase is brief (perhaps weeks to months) but highly productive.

Phase 2b: Continued fast progress, though slower than 2a. The most obvious low-hanging fruit has been picked, but researchers still benefit from working on the actual system, assisted by advanced AI tools. This might last around a year.

Phase 2c: Progress slows to a rate similar to Phase 1, the benefits of having the actual system now roughly offset by the depletion of tractable problems. This subphase might last several years.

Phase 2d: Ultimately progress becomes very slow, consisting of fundamental research into alignment science or the development of qualitatively new architectures. This continues indefinitely.

Figure 3 illustrates the qualitative picture. The key feature is that safety progress is front-loaded within Phase 2.

Figure 3. Qualitative picture of risk in a multiphase model

To make this concrete, Table 8 shows the optimal pause durations (from the start of Phase 2) for eight different scenarios. (For details, see Appendix E.)

TABLE 8: A multiphase model: several scenarios

| # | Phase 1 | 2a | 2b | 2c | 2d | 1% | 5% | 20% | 50% | 80% | 95% | 99% |

| ① | 0y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 5%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Wait 3.6m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.3y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 6.3y |

| ② | 0y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 10%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Wait 3.6m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 4.1y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 6.3y |

| ③ | 5y 5%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 5%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Wait 3.6m | Wait 9.4m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 2.2y | Wait 5.0y | Wait 5.7y |

| ④ | 5y 10%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 10%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Wait 1.5m | Wait 3.6m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 3.0y | Wait 4.5y | Wait 4.9y |

| ⑤ | 10y 5%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 5%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Wait 1.2m | Wait 3.6m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.3y |

| ⑥ | 10y 10%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 10%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Launch asap | Wait 3.6m | Wait 1.0y | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.3y |

| ⑦ | 20y 5%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 5%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Launch asap | Wait 3.6m | Wait 11.1m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.3y |

| ⑧ | 20y 10%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 10%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Launch asap | Launch asap | Wait 3.6m | Wait 3.6m | Wait 3.6m | Wait 3.6m |

We see that for a wide range of initial risk levels and rates of safety progress, the optimal strategy is to implement a short pause once we enter Phase 2. If the “windfall” available in subphases 2a and 2b is significant, the optimal pause is often measured in months or a small number of years. Beyond that point, the safety benefits of further waiting tend to be outweighed by the continuing costs of mortality and temporal discounting.

If we instead consider jointly optimizing over both and —so that the decision-maker can choose how long Phase 1 lasts (up to the maximum given by each default scenario) and then also choose how long to pause after AGI-capability is attained—we get the results shown in Table 9. (For ease of comparison, the times are expressed relative to the point at which launch would have occurred “by default” in each scenario, i.e. if there were neither acceleration of Phase 1 nor any subsequent pause. For example, in scenario 4, where the default Phase 1 duration is 5 years, “Wait −3.7 y” means launch occurs 1.3 years after the beginning of Phase 1. Likewise, “launch asap” here denotes the time as it did previously, the point at which Phase 2 would have commenced by default.)

TABLE 9: Joint optimization over Phase 1 and Phase 2

| # | Phase 1 | 2a | 2b | 2c | 2d | 1% | 5% | 20% | 50% | 80% | 95% | 99% |

| ① | 0y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1y 25%/y | 5.0y 5%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Wait 3.6m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.3y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 6.3y |

| ② | 0y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1y 25%/y | 5.0y 10%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Wait 3.6m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 4.1y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 6.3y |

| ③ | 5y 5%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1y 25%/y | 5.0y 5%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Wait −5.0y | Wait −4.7y | Wait −3.7y | Wait −3.7y | Wait 2.2y | Wait 5.0y | Wait 5.7y |

| ④ | 5y 10%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1y 25%/y | 5.0y 10%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Wait −5.0y | Wait −4.7y | Wait −3.7y | Wait −11.3m | Wait 3.0y | Wait 4.5y | Wait 4.9y |

| ⑤ | 10y 5%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1y 25%/y | 5.0y 5%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Wait −10.0y | Wait −9.7y | Wait −8.7y | Wait −8.7y | Wait −2.8y | Launch asap | Wait 8.6m |

| ⑥ | 10y 10%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1y 25%/y | 5.0y 10%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Wait −10.0y | Wait −9.7y | Wait −8.7y | Wait −5.9y | Wait −2.0y | Wait −5.6m | Wait −1.3m |

| ⑦ | 20y 5%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1y 25%/y | 5.0y 5%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Wait −20.0y | Wait −19.7y | Wait −18.7y | Wait −18.7y | Wait −12.8y | Wait −10.0y | Wait −9.3y |

| ⑧ | 20y 10%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1y 25%/y | 5.0y 10%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Wait −20.0y | Wait −19.7y | Wait −18.7y | Wait −15.9y | Wait −12.0y | Wait −10.5y | Wait −10.1y |

We see that in many scenarios and for many initial levels of risk, if the decision-maker is free to jointly optimize over both AGI development time and subsequent pausing, it is optimal to launch earlier than would have happened by default: these are the cells with blue background. (In scenarios 1 and 2, acceleration is impossible since Phase 1 has zero duration.)

Additionally, there are several scenarios in which, although launch occurs in Phase 2 after some period of pausing, it is still optimal to accelerate to some extent in Phase 1: these are the cells that do not have blue background but do have blue borders. This can happen because the rate of risk reduction is faster in Phase 2a and 2b than during Phase 1. There is thus a special value in being able to pause for at least a short while after AGI-capability has been attained before deploying it; and it can be worth going faster through Phase 1 in order to harvest these rapid safety gains while still keeping the overall time until AGI deployment tolerably short.

Shifting mortality rates

We have been assuming a constant background mortality rate until the launch of AGI, yet it is conceivable that it could change around the time when AGI-capability is attained (but before it is fully deployed).

Pessimistically, the world might become more dangerous with the introduction of near-AGI capabilities. For example, specialized AI systems could proliferate the capability to produce (new and more lethal) bioweapons, enable vast swarms of autonomous drones, precipitate mayhem by destabilizing our individual or collective epistemic systems and political processes, or raise geopolitical stakes and urgency in such a way as to trigger major war.

Optimistically, one might hope that near-AGI systems would enable breakthroughs in medicine that reduce mortality rates. However, substantial mortality reductions seem unlikely to materialize quickly, since many medical innovations must pass through extensive clinical trials and then require further time to achieve globally significant scale. Near-AGI systems could, of course, also have many other positive effects; yet except possibly for medical applications, it seems unlikely that they would have a big immediate impact on average death rates, since most people who are currently dying are succumbing to age-related and other medical issues.

On balance, therefore, if there is a dramatic change in global mortality just around the time when AGI becomes possible, it seems likelier to be for the worse than for the better. This adds to the reasons for keeping wait times relatively short after AGI-capability (or near-AGI capability that starts having dangerous applications) has been attained.

Yet if a medical breakthrough were to emerge—and especially effective anti-aging therapies—then the optimal time to launch AGI could be pushed out considerably. In principle, such a breakthrough could come from either pre-AGI forms of AI (or specialized AGI applications that don’t require full deployment) or medical progress occurring independently of AI. Such developments are more plausible in long-timeline scenarios where AGI is not developed for several decades.

Note that for this effect to occur, it is not necessary for the improvement in background mortality to actually take place prior to or immediately upon entering Phase 2. In principle, the shift in optimal timelines could occur if an impending lowering of mortality becomes foreseeable; since this would immediately increase our expected lifespan under pre-launch conditions. For example, suppose we became confident that the rate of age-related decline will drop by 90% within 5 years (even without deploying AGI). It might then make sense to favor longer postponements—e.g. launching AGI in 50 years, when AI safety progress has brought the risk level down to a minimal level—since most of us could then still expect to be alive at that time. In this case, the 50 years of additional AI safety progress would be bought at the comparative bargain price of a death risk equivalent to waiting less than 10 years under current mortality conditions.

Table 10 shows the effects of postulating a precipitous drop in background mortality upon entering Phase 2—all the way to , i.e. the rate that corresponds to a life expectancy of 1,400 years, same as what we have been assuming successful AGI would achieve. (Other parameters are the same as in Table 8; and we are assuming here that Phase 1 cannot be accelerated.)

TABLE 10: Pre-deployment mortality plummeting to 1/1400 (medium temporal discounting)

| # | Phase 1 | 2a | 2b | 2c | 2d | 1% | 5% | 20% | 50% | 80% | 95% | 99% |

| ① | 0y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 5%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Wait 1.1m | Wait 4.9m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 18.0y | Wait 24.7y | Wait 26.4y |

| ② | 0y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 10%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Wait 1.1m | Wait 4.9m | Wait 3.3y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 8.9y | Wait 14.5y | Wait 15.9y |

| ③ | 5y 5%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 5%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Wait 3.6m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 7.4y | Wait 13.6y | Wait 15.1y |

| ④ | 5y 10%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 10%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Wait 3.6m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 6.1y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 6.3y |

| ⑤ | 10y 5%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 5%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Wait 3.6m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.5y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 6.3y |

| ⑥ | 10y 10%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 10%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Wait 3.6m | Wait 11.2m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 5.2y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 6.3y |

| ⑦ | 20y 5%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 5%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Wait 3.6m | Wait 9.8m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.3y | Wait 2.5y | Wait 3.3y |

| ⑧ | 20y 10%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 10%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Launch asap | Wait 3.6m | Wait 3.6m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.3y |

We see that the optimal pause duration becomes longer—but not dramatically so. That the impact is fairly limited is due in part to safety gains being front-loaded, with diminishing returns arriving quickly after entering Phase 2. And in part it is due to the “medium”-level temporal discounting () dominating the mortality rate.

Table 11 shows the same scenarios but with the “low” discount rate (). This does lead to longer wait times, especially in scenarios where the initial AI risk is so high that even after the sizable reductions during Phase 1 and Phases 2a–c, the level of risk remains too high for comfort.

TABLE 11: Pre-deployment mortality plummeting to 1/1400 (low temporal discounting)

| # | Phase 1 | 2a | 2b | 2c | 2d | 1% | 5% | 20% | 50% | 80% | 95% | 99% |

| ① | 0y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 5%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Wait 3.6m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 5.1y | Wait 14.9y | Wait 33.8y | Wait 41.2y | Wait 43.0y |

| ② | 0y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 10%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Wait 3.6m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 22.5y | Wait 29.6y | Wait 31.3y |

| ③ | 5y 5%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 5%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Wait 3.6m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.3y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 22.2y | Wait 29.4y | Wait 31.2y |

| ④ | 5y 10%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 10%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Wait 1.6m | Wait 4.6m | Wait 3.2y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 7.8y | Wait 9.3y |

| ⑤ | 10y 5%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 5%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Wait 1.4m | Wait 3.7m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 10.7y | Wait 17.7y | Wait 19.4y |

| ⑥ | 10y 10%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 10%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Wait 3.6m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 6.3y |

| ⑦ | 20y 5%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 5%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Wait 3.6m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.3y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 6.3y |

| ⑧ | 20y 10%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 10%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Wait 1.1m | Wait 3.6m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.3y | Wait 2.2y | Wait 2.6y |

Thus, if the background mortality risk is greatly reduced, then those with a low discount rate would be willing to wait a long time in order for AI risk to decline to a very low level. Note, however, that even if people stopped dying altogether, it could still be optimal to launch AGI eventually—and in fact to do so without extremely long delays—provided only there is a significant quality-of-life differential, a nontrivial temporal discount rate, and that AI safety continues to improve appreciably.

For contrast, Table 12 illustrates the situation for the opposite scenario, where mortality rates rise upon entering Phase 2. Unsurprisingly, this shortens optimal pause durations. The effect for the parameter-setting used in this table—a doubling of the mortality rate—is fairly modest. It would be more pronounced for greater elevations in the level of peril.

TABLE 12: Pre-deployment mortality rising to 1⁄20 (medium temporal discounting)

| # | Phase 1 | 2a | 2b | 2c | 2d | 1% | 5% | 20% | 50% | 80% | 95% | 99% |

| ① | 0y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 5%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Wait 2.9m | Wait 6.6m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 2.6y | Wait 5.0y | Wait 5.6y |

| ② | 0y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 10%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Wait 2.9m | Wait 6.6m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 4.8y | Wait 6.3y | Wait 6.3y |

| ③ | 5y 5%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 5%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Launch asap | Wait 3.6m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.3y |

| ④ | 5y 10%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 10%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Launch asap | Wait 3.6m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.7y |

| ⑤ | 10y 5%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 5%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Launch asap | Wait 3.6m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.3y |

| ⑥ | 10y 10%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 10%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Launch asap | Wait 3.6m | Wait 3.6m | Wait 1.2y | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.3y |

| ⑦ | 20y 5%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 5%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Launch asap | Wait 3.6m | Wait 3.6m | Wait 1.1y | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.3y |

| ⑧ | 20y 10%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1.0y 25%/y | 5.0y 10%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Launch asap | Launch asap | Wait 3.0m | Wait 3.6m | Wait 3.6m | Wait 3.6m |

Safety testing

AI safety work can provide at least two types of benefit: first, it can improve the nature of an AI system so that it is less likely to cause catastrophic harm if deployed; second, it can provide information about that nature, so that we can better judge whether to deploy it or to keep working to make it safer. The previous sections modeled both effects with a single parameter (the “rate of AI safety progress”). If we are willing to tolerate a more complicated setup, we can instead treat them separately. This leads to models where what is determined in advance is not an optimal launch time but an optimal policy that specifies—conditional on whatever safety information is then available—whether to launch or to continue working and testing.

To keep the setup manageable, we graft a simple testing process onto the multiphase model from the previous section. Once AGI‑capable systems exist (the start of Phase 2), the true catastrophe probability at that time is unknown: it could be any of seven values, corresponding to the initial risk levels used earlier (1 %, 5 %, 20 %, 50 %, 80 %, 95 %, or 99 %). We assume a uniform prior over these possibilities. Safety work reduces the underlying risk over time following the same multiphase schedule as before: Phase 1 with moderate progress, followed (once AGI‑capable systems exist) by a brief period of very rapid safety improvement (Phase 2a), a somewhat slower but still fast phase (2b), a medium‑progress phase (2c), and then a long tail of very slow progress (2d).

Safety tests are triggered by safety progress rather than by clock time. Starting from the moment AGI‑capable systems are available, a new test is performed every time safety work has reduced the system’s intrinsic catastrophe probability by another 20 % relative to the last test. This reflects the idea that developing informative tests is itself part of safety work: as we make the system safer, we also learn how to probe it more effectively. If the underlying risk at the moment of testing is , the test returns “fail” with probability and “pass” with probability . Systems with very high intrinsic riskiness therefore tend to fail tests repeatedly, whereas fairly safe systems mostly pass—even if their remaining risk is still substantial. In particular, these tests usually cannot distinguish reliably between, say, ten and twenty per cent risk at launch; they are better at separating “clearly terrible” from “not obviously terrible”.

We can formalize this setup as a partially observed Markov decision process (POMDP) and compute the optimal policy numerically (see Appendix G for details). Table 13 shows the expected delays (counting from the beginning of Phase 2).

TABLE 13: Periodic safety tests

| # | Phase 1 | 2a | 2b | 2c | 2d | 1% | 5% | 20% | 50% | 80% | 95% | 99% |

| ① | 0y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1y 25%/y | 5.0y 5%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Wait 1.4y | Wait 1.7y | Wait 2.7y | Wait 4.9y | Wait 7.3y | Wait 8.6y | Wait 8.9y |

| ② | 0y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1y 25%/y | 5.0y 10%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Wait 1.6y | Wait 2.0y | Wait 3.2y | Wait 4.8y | Wait 5.8y | Wait 6.1y | Wait 6.1y |

| ③ | 5y 5%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1y 25%/y | 5.0y 5%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Wait 1.1y | Wait 1.2y | Wait 1.7y | Wait 3.1y | Wait 4.7y | Wait 5.3y | Wait 5.5y |

| ④ | 5y 10%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1y 25%/y | 5.0y 10%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Wait 4.7m | Wait 6.6m | Wait 1.3y | Wait 3.1y | Wait 4.8y | Wait 5.4y | Wait 5.6y |

| ⑤ | 10y 5%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1y 25%/y | 5.0y 5%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Wait 5.1m | Wait 6.1m | Wait 10.5m | Wait 1.8y | Wait 3.1y | Wait 3.7y | Wait 3.9y |

| ⑥ | 10y 10%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1y 25%/y | 5.0y 10%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Wait 3.9m | Wait 5.3m | Wait 9.2m | Wait 1.2y | Wait 1.5y | Wait 1.7y | Wait 1.7y |

| ⑦ | 20y 5%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1y 25%/y | 5.0y 5%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Wait 3.9m | Wait 5.3m | Wait 9.2m | Wait 1.1y | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.3y | Wait 1.3y |

| ⑧ | 20y 10%/y | 0.3y 70%/y | 1y 25%/y | 5.0y 10%/y | ∞ 2%/y | Launch asap | Launch asap | Wait 1.9m | Wait 3.4m | Wait 4.5m | Wait 5.2m | Wait 5.4m |

We observe that in most cases, the optimal policy results in an expected short (but greater-than-zero) delay, to take advantage of the rapid safety progress and concomitant opportunities gaining more information about the system’s riskiness available in Phases 2a and 2b. Conditional on the system’s initial riskiness being high when entering Phase 2, waiting times are longer; whereas when this is not the case, the optimal policy typically recommends launching within a year or two.

Note that Table 13 is not directly comparable to Table 8 (which represents the multiphase model analyzed earlier, the one most similar to the present model). This is because earlier we assumed that the decision-maker knew the initial riskiness of the system, whereas in the current model the agent starts out with a uniform probability distribution over the seven possible initial risk levels. If we want to pinpoint the difference that testing makes, we need to compare it to a baseline in which the agent starts out with the same agnostic distribution yet gains no further information from safety testing. Table 14 presents the result of such a comparison.

TABLE 14: Difference in outcomes from safety tests

| # | Avg launch (no tests) | Avg launch (tests) | Δ wait | Risk (no tests) | Risk (tests) | Δ risk | Utility gain |

| ① | 3.90y | 5.05y | +1.15y | 22.9% | 20.6% | -2.2% | +3.58% |

| ② | 6.30y | 4.23y | -2.07y | 15.4% | 16.9% | +1.5% | +2.95% |

| ③ | 1.30y | 3.23y | +1.93y | 20.2% | 17.3% | -2.9% | +1.31% |

| ④ | 1.50y | 3.03y | +1.53y | 15.1% | 11.5% | -3.6% | +1.71% |

| ⑤ | 1.30y | 2.05y | +0.75y | 15.7% | 14.8% | -0.9% | +0.37% |

| ⑥ | 1.30y | 1.09y | -0.21y | 9.1% | 9.1% | +0.0% | +0.45% |

| ⑦ | 1.30y | 0.93y | -0.37y | 9.4% | 9.6% | +0.3% | +0.28% |

| ⑧ | 0.30y | 0.25y | -0.05y | 4.2% | 4.2% | +0.0% | +0.06% |

We see that testing increases expected utility, sometimes by shortening the expected time-to-launch and sometimes by reducing the expected risk-at-launch. (That the expected utility gains look quite small in percentage terms is not particularly significant—this is driven by the infrequency and low sensitivity we assume of the tests and by other modeling assumptions. In reality, tests may also provide value by guiding future safety work in more productive directions.)

Figure 4 further illustrates how safety testing affects launch times. The dashed lines indicate where launches occur without safety testing (but with the agnostic prior over initial riskiness levels) for each of the eight scenarios. The solid lines show the cumulative probability distributions for the optimal policy with safety testing. We see that safety testing results in early launches in worlds where tests repeatedly pass, and later launches where tests keep failing and the posterior remains pessimistic.

FIGURE 4: Cumulative distribution functions of launch times with versus w/o safety tests

The main takeaway is that once system safety is uncertain, and future tests may provide information about how risky a system is, the relevant object is not a single optimal launch date but an optimal policy that conditions on evidence. Such a policy does something no fixed delay can do: it launches quickly when tests indicate the system is likely to be safe enough, but delays when tests reveal signs of danger. (The value of safety testing, however, depends not only on the quality of the tests themselves but—crucially—also on whether decision‑makers are willing and able to let deployment decisions actually respond to what the tests reveal.)

Distributional considerations

We have analyzed the situation from the standpoint of the current world population as a whole. However, we need to acknowledge that the prudentially optimal timing for superintelligence is not the same for everyone.

One important factor of divergence is that people’s mortality rates differ. Elderly people face a higher likelihood in the status quo of dying in the near future, while the young and hale could tolerate longer delays without accumulating an excessive risk of perishing before the main event.

Another factor is that those whose present quality of life is poor could rationally accept a higher risk of death for a shot at experiencing the great abundance and efflorescence that successful AGI would enable than those who are currently enjoying (what in present era is regarded as) a high standard of living.

There are therefore conflicts between different demographics over what is prudentially optimal regarding the timing of AGI. Other things equal, those who are old, sick, poor, downtrodden, miserable—or who have higher discount rates or less concave preferences over future quality-adjusted life years—should prefer earlier AGI launch dates compared to people who are comparatively satisfied and secure in the status quo.[14]

In the public policy literature, social welfare functions are often designed to include a prioritarian or egalitarian skew, such that a higher desirability is assigned (ceteris paribus) to outcomes in which the worst-off receive a given boost to their welfare than to ones in which a boost of equal magnitude is given to those who are already better-off.[15] If such priority is given to the worse off, and we combine this stipulation with the observations already made about the divergent prudential interests of different demographics, there may be implications for what is globally optimal regarding AI timelines.

In particular, the optimal timeline to superintelligence is likely shorter on a prioritarian view than it is on a neutral (person-affecting) utilitarian stance. This is partly because the worse off have less to lose and more to gain from rolling these dice. And partly it is because, in the case of the sick and the elderly, they have less ability to wait and roll the dice later when the odds may be more favourable. There is therefore a prioritarian argument for accelerating timelines beyond what the preceding analysis suggests.

Let us examine these issues a little more closely. One possible thought one might have is that the younger age structure in low-income countries would reduce the strength of the aforementioned prioritarian argument for shorter timelines, by introducing a correlation between being worse off and having longer remaining life expectancy—so that poor people in the developing world would have a prudential interest in longer AGI timelines compared to their better-off counterparts in rich countries. However, although the population does skew younger in poor countries, this is not enough to make up for the generally higher life expectancy in rich countries. The difference in life expectancy between rich and poor countries—which can exceed 25 years at birth when comparing the richest and poorest nations—narrows considerably when calculated as a population-weighted average of remaining years, due to the younger age structure in poorer countries. However, it does not close, let alone reverse.[16] While some convergence in life expectancy between poor and rich countries might be expected to occur during the remaining lifetime of people living in poor countries, it still seems plausible that, on average, people who are currently economically unfortunate can also expect to die sooner under default conditions than people who are currently economically fortunate. This positive correlation between poverty and lower remaining life expectancy strengthens the prioritarian case for faster timelines (compared to the distribution-agnostic analysis of the preceding sections).

One may also regard lifespan itself as a contributing factor in how fortunate a person is, and hence—on a prioritarian view—in how strong a claim they have to marginal resources or weighting of their marginal interests in the context of social planning. There are several different possible ways in which lifespan-related variation could be taken to influence somebody’s baseline welfare level:

i. Remaining life years. One might hold that (ceteris paribus) persons with more remaining life years are better off than those with fewer years left, since it seems unfortunate to be in a condition in which one is soon about to get sick and die.

If one adopts this stance, then the prioritarian skew towards shorter timelines would be amplified. This is because older people—whose interests favor shorter timelines—would be weighted more heavily by this metric, since it would adjudge them comparatively unfortunate in the status quo.

ii. Life years already had. One might hold that (ceteris paribus) persons who have lived longer are better off, on grounds that they have gotten to feast more on life.

If one adopts this stance, then the prioritarian skew would be pulled in the direction favoring longer timelines, since the metric implied by (ii) would tend to deem older people as better off and hence less deserving of marginal consideration. It would not necessarily pull it far enough to make the prioritarian favor longer timelines all things considered compared to a neutral (non-prioritarian) criterion, since there are other categories of badly-off people (aside from, supposedly, the young) and who may have interests that differentially benefit from shorter timelines.

However, in any case, (ii) seems like a mistaken way to reckon. Consider two persons, a 10-year-old and a 20-year-old, both of whom have a genetic condition from which they will die at age 30, unless they receive a therapy, of which only one dose is available—in which case they live to age 50. It seems implausible to maintain that the 10-year-old has a stronger claim to the therapy just because he hasn’t lived as long as the 20-year-old. It seems more plausible that their claims are equally strong—or, if not, then perhaps that the 20-year-old has a stronger claim (as would be implied by (i)).

A more plausible way to capture whatever intuition might appear to support (ii) would be:

iii. Total life years. One might hold that (ceteris paribus) persons whose total lifespans are longer are better off, since their endowment of life is greater.

This would accord the 10-year-old and the 20-year-old in the previous example equal weight, since they have the same baseline length of lifespan. When coupled with a prioritarian ethic, stance (iii) results in greater weight being placed on the interests of those whose lives in the default condition would be shorter.

So whose lives would, absent AGI, be shorter: the lives of the old or the lives of the young? On the one hand, the old have already survived all the hazards that kill some people prematurely. On the other hand, the young can expect to benefit from many decades of economic and medical progress which might prolong their lives. If we extrapolate recent rates of increases in life expectancy, in wealthy countries, we may get a U-shaped curve: younger people and the very oldest people have the longest total life expectancy, with the nadir occurring for those who are around age 80. (Intuitively: somebody who’s a centenarian has already lived longer than a newborn is likely to do, while a child has an advantage over people who are in their forties because the child is very likely to make it to forty and then gets benefit from four more decades of medical progress.) Since there are many more people who are substantially younger than 80 than who are substantially older than 80, this means there is a positive correlation between youth and total life expectancy. Hence (iii) induces an overall prioritarian downweighting of the interests of the young in wealthy countries. This would shorten the optimal timeline to AGI. In poor countries, however, the relationship may be more complicated due to high infant mortality: newborns have low expected total lifespans; young adults, high expected total lifespans, older adults, lower expected total lifespans; and the very old, high expected total lifespans. Absent a detailed quantitative analysis, it is not obvious how that adds up.

If one expects a radical breakthrough in life extension will happen, even in the absence of AGI, years from now, which will enable people to live very long lives, such as two hundred years (or even to attain longevity “escape velocity”), then a discontinuity is introduced whereby those who would live less than years without AGI are comparatively a lot more unfortunate according to (iii) than those who without AGI have more than years left to live. Those with less than years left to live without AGI would thus have their interests upweighted in a prioritarian social welfare function. This would increase the shift towards shorter timelines being optimal, assuming that is within the lifetime of at least some significant fraction of currently living people.

Note that these effects from prioritarian upweighting of those with shorter total life expectancy—or those with shorter remaining life expectancy, if we adopt stance (i)—are additional to the effect that results from whatever extra benefit there is to adding life years to otherwise short lives that stem directly from diminishing marginal utility in life years (or QALYs). In other words, there are two possible reasons for giving an extra life year to a short-lived person rather than to a long-lived person, which are analogous to two possible reasons for giving a hundred dollar bill to a poor person rather than to a rich person: first, the poor person may derive a greater benefit from the hundred dollars; and second, the poor person might be overall worse off than the rich person, and would therefore—on a prioritarian ethic—have a stronger claim to marginal benefits (such that even if we suppose that the rich person would derive an equally large benefit from the hundred dollar bill—perhaps they are out of cash and need a taxi home—it would still be better for it to go to the poor person).

Yet another possible stance on how life chronology could be a prioritarian weight-factor is that there is some specific number of life years—for instance, the traditional three-score-and-ten—such that it is bad for a person to die earlier than that yet not significantly better to live beyond it. The metaphor might be that a human is like a cup of limited capacity, and once it’s been filled up with life there’s no value to keep pouring.

iv. Full cup. One might hold that it is unfortunate for somebody to die before the age of approximately seventy, but somebody who lives much beyond seventy is not thereby significantly better off, since they’ve already had a full life.[17]

This stance would have four relevant implications. First, it would reduce the value of AGI success, because some of the supposed upside consisted of the (exponentially time-discounted) value of lifespans much longer than the currently typical one for humans. (However, another part of the upside—the prospect of a greatly improved quality of life—would remain important.) Second, it would tilt the prioritarian skew in favor of the young, since they are not guaranteed in the pre-AGI default condition to reach the “full cup” number of life years that the old have already attained, thus making the young count as more unfortunate, thus giving their interests (which favor longer timelines) greater weight. Third, it would increase the downside for the young of early AGI launch, since—unless the risk has been brought down to quite a low level—an AGI launch could amplify the threat that the young will fail to reach their normal allotment of years. And fourth, since this increased downside pertains exclusively to the young, whereas the old, according to (iv), have little to lose from an AGI launch as they are already home and dry, it would tilt prioritarian concern even further towards favoring the interests of the young. The upshot would be that optimal AGI timelines, if one adopted the “full cup” stance, would become significantly longer.

However, even if the “full cup” stance might have some prima facie appeal, it is plausible that the intuitions that appear to support it are rooted—at least in substantial part—in a conflation between chronological age and contingently associated circumstances of age. In contemporary settings, old age is associated with multimorbidity, declining capacities, loneliness, pain, loss of autonomy, a sense of being a burden, and bleak future prospects. It would hardly be remarkable if additional life years under those conditions have limited appeal to many.[18] This might lead one to believe that seventy years (or some “normal lifespan” in that neighborhood) is all we need to max out our utility function in life years. But the most it would really show is that in present circumstances we gain little from living much beyond that age. In other circumstances, we may gain a lot. In particular, if an AGI-breakthrough enables the restoration of full health and youthful vigor, and a return or even strengthening of our previously lost capacities—and pulls open the curtains to a long continued existence, together with friends and family who can also expect to stick around for a long time, in a world that is dawning on a new age, immeasurably richer, more promising, and teeming with marvels than any earlier era—then why should additional life years stop being valuable for somebody just because seventy life years have passed since they were born? In such a scenario, would we not rather all be like children again—with the potential before us so greatly outstripping our comparatively paltry past?

This suggests that we should reject the “full cup” stance as a fundamental evaluative principle, and specifically reject its application in the context of transformative AI, where many of the usual conditions of life years at old age are stipulated not to obtain. It is also worth noting that even under current (often very bad) conditions, those who seem best placed to judge the value of continued life at old age—namely, those who actually are in that situation and have first-hand knowledge of what it is like—often deny the stance and place a high value on remaining alive longer. For example, in one multicenter study of hospitalized patients aged 80+, more than two-thirds were willing to give up at most one month of a remaining year for “excellent health”.[19] Surrogate decision-makers systematically underestimated their reluctance to trade away time. When patients who were still alive a year later were asked the same question again, they were willing to trade even less time for better health than at baseline.

We have focused on distributional considerations that are fairly directly tied to when AGI is developed. There are of course many other potentially important distributional considerations that arise in the context of AGI. For example, citizens of a country that leads AGI development might benefit more than citizens of other countries; and individuals who directly participate in a successful AGI launch might gain disproportionate profits and glory. Although who and how may be correlated in various ways to when, these broader distributional questions fall outside the scope of this paper.

Other-focused prudential concerns

A different set of considerations arises if we expand our conception of what might lie in the prudential interest of a person to include the welfare of other persons they strongly care about. For example, while it might be in the narrow self-interest of an old person for superintelligence to be launched very soon, they might prefer a somewhat delayed launch because they also care about their grandchildren who have a much longer remaining life expectancy under pre-AGI conditions than they themselves do.

However, if we take into account these kinds of preferences, we should also take into account preferences going in the other directions: younger people who, for their own part, might benefit from longer timelines yet may prefer somewhat shorter timelines because they care about others who are closer to dying. Just as we can love our children and grandchildren, we can also love our parents and grandparents. So this type of concern for kin might total up to roughly a wash.

With regard to caring for our friends (or admired strangers), it is likewise unclear which way the correlation goes between somebody’s age and the number of people who care about them. The very old may have fewer people who care about them because many of their friends have already died; but the very young may also have fewer friends who care about them because they have not met many people yet or have not known them for long.

On a prioritarian view, including other-focused concerns among our prudential interests might induce a slight shift in the direction of longer timelines. Suppose we assume a symmetric degree of average care between the young and the old. Suppose, further, that the old are on average worse off than the young in the default condition (because of their shorter remaining and total life expectancy); so that a prioritarian reckoning upweights the interests of the old in determining the optimal social policy. Then the prioritarian upweighting of the interests of the old means that the interests of those whom the old care about receive extra weight (relative to what they would get if we didn’t include other-focused concerns in our conception of what is prudentially desirable for somebody). Since on average the people whom old people care about are younger than they are themselves, this would shift some emphasis towards younger people, whose interests are served by longer timelines. Any such effect, however, is quite subtle and second-order.

Theory of second best

We have thus far asked the question about the optimal timing for superintelligence (from a person-affecting perspective) in an abstracted way—as if the world had a knob for different dates and your job was to turn it to the correct setting. In reality, the situation is more complex. Nobody has full control over AGI timelines, and different actors have different preferences. The ideal timing may not be achievable, or might be achievable only through methods that would carry a significant risk of making the timing much worse than it would otherwise have been. Furthermore, interventions aimed at influencing when superintelligence arrives may have other important consequences besides their effect on timing. For these reasons, while the preceding discussion highlights some relevant background considerations, it does not on its own imply particular policy recommendations.

While a full policy analysis would require bringing into consideration many facts and arguments that are out of scope for this paper, it may be useful to briefly list some of the ways that an AI pause, or efforts to bring about such a pause, could have undesirable effects (aside from simply delaying the arrival of the benefits that successful AGI could bring):

The pause occurs too early. People conclude that it was pointless, and become less willing to pause later when it would have been useful.

The call for a pause results in poorly designed or incomplete regulation, producing safety theater that adds costs and bureaucracy and slows useful applications, while doing nothing to reduce the real risks. Compliance and box-ticking crowd out substantive work on risk reduction.

A pause is implemented, but the developments it aims to forestall continue anyway—just elsewhere. Work may be driven underground, or shift towards less scrupulous actors or less cooperative states.

The pause has an exemption for national security, pushing AI activities away from the civilian into the military sector. The result may be greater emphasis on destructive uses, lower transparency and democratic oversight, amplified AI-assisted coup risk or power concentration risk, and perhaps less competent alignment efforts.

There are calls for a pause but they go unheeded—and no catastrophe occurs. Those who warned of danger are discredited, making it harder for future calls for AI safety work to be taken seriously.

The push for a pause highlights the strategic importance of the technology, intensifying geopolitical AI competition.

An international agreement is reached on pausing, but this creates a prisoner’s dilemma in which some parties cheat (driving developments into covert programs) or triggers geopolitical conflict when some countries accuse others of cheating.

A pause is implemented, leading to economic recession and general pessimism and lowered hopes for the future. People see the world more as a zero-sum battle for a limited set of resources, increasing conflict and tribalism.

A pause prolongs the period during which the world is exposed to dangers from applications of already developed levels of AI (and to risks independent of AI), which more advanced AI could have helped mitigate.

To enforce a pause, a strong control apparatus is created. The future shifts in a more totalitarian direction.

There is a pause on AI development, yet progress in hardware and algorithm development continues. When the pause is eventually lifted, there is a massive compute and/or algorithm overhang that leads to explosive advances in AI that are riskier than if AI had advanced at a steadier pace throughout. The world will also not have had the opportunity to learn from and adapt to living with weaker AI systems. (Or in a more extreme case, the pause holds until dangerous models or superintelligence can be implemented on consumer-grade hardware, making it ungovernable.)- Agitation for a pause leads to extremism. Some people become radicalized or violent. Attitudes towards AI become polarized to such an extent as to make constructive dialogue difficult and destroy the ability of institutions to pass nuanced adaptive safety policy.

The push for a pause galvanizes supporters of AI to push back. Leading AI firms and AI authorities close ranks to downplay risk, marginalizing AI safety researchers and policy experts concerned with AI risk, reducing their resourcing and influence.A pause, initially sold as a brief moratorium to allow social adjustments and safety work to catch up, calcifies into a de facto permaban that prevents the immense promise of superintelligence from ever being realized—or is indefinitely extended without ever being formally made permanent.[20]

Of course, there are also some potentially positive side effects that might come from calls to bring about a pause even if they fail in their main aim. For example, they might lead to an increase in funding for AI safety work as a more acceptable alternative to pausing, or generally stimulate the world to more seriously prepare for AGI. Still, the potential ways that pausing or pushing for pausing could backfire are many and quite plausible.

The profile of potential upsides and downsides of a pause or delay looks different depending on the mechanics of implementation and the context in which it takes place. We have already touched on the idea that the safety benefit of a pause of a given duration seems likely to be much greater if it occurs at a late stage—ideally, once the capacity for AGI exists, and perhaps even a fully implemented system, yet prior to maximum scaleup or general deployment; since extra time for safety testing, oversight, and final adjustment may be especially impactful during that stage. The scope of and causal process inducing the pause is also relevant. Consider the following cases:

Frontrunner unilaterally burning lead. At the time when AGI becomes possible, one developer might have a technological lead over its competitors. It could choose to burn some or all of its lead to implement extra precautions while remaining ahead. This type of pause is relatively attractive, as it has less risk of producing many of the downsides listed above. It does not rely on the creation of a regulatory apparatus or enforcement regime, and it is less likely to result in a permanent abandonment of superintelligence. The pause is self-limiting, as it expires once a competitor catches up. If the case for additional safety precautions is very clear and strong, this competitor may also be persuaded to agree to halt (either unilaterally or in coordination with the frontrunner, perhaps with some nudging from the government), thus extending its duration. But eventually, as more competitors reach similar capability levels, the pause naturally expires. The scope for this kind of pause, however, is reduced in a highly competitive environment. At present, it is unclear who is ahead; and whatever lead they have is measured in a small number of months.

Government-imposed moratorium. This brings in more of the potential failure modes and side-effects that we listed. Risks of bureaucratization, militarization, self-coups, etc. are increased. The maximum duration of the pause is extended, and there is a greater risk that it would remain in place for longer than it ought to. It matters how the government action was brought about: if it is the result of technocratic pragmatics, the risk of it becoming too long or permanent is lower than if it comes about as a result of a general political anti-AI mobilization that stigmatizes the very idea of superintelligence. Instead of an outright moratorium, there could be regulation that permits the development and deployment of AGI only when safety standards have been met—this might be theoretically superior to an outright ban, but in practice it could be difficult to specify sensible criteria with enough precision.