Ruling Out Everything Else

Clear communication is difficult. Most people, including many of those with thoughts genuinely worth sharing, are not especially good at it.

I am only sometimes good at it, but a major piece of what makes me sometimes good at it is described below in concrete and straightforward terms.

The short version of the thing is “rule out everything you didn’t mean.”

That phrase by itself could imply a lot of different things, though, many of which I do not intend. The rest of this essay, therefore, is me ruling out everything I didn’t mean by the phrase “rule out everything you didn’t mean.”

Meta

I’ve struggled much more with this essay than most. It’s not at all clear to me how deep to dive, nor how much to belabor any specific point.

From one perspective, the content of this essay is easy and obvious, and surely a few short sentences are all it takes to get it across?

From another perspective, if this were obvious, more people would have discovered it, and if it were easy, more people would do it, and if more people knew and acted in accordance with the below, the world would look very different.

So that’s evidence that my “easy and obvious” intuition is typical minding or similar, and in response I’ve decided to err on the side of going slowly and being more thorough than many readers will need me to be. If you find yourself impatient, and eager to skip to the end, I do not have a strong intuition that you’re making a mistake, the way I have in certain other essays.

I note that most of my advice on how to communicate clearly emerges fairly straightforwardly from a specific model of what communication is—from my assumptions and beliefs about what actually happens when one person says words and other people hear those words. So the majority of this essay will be spent transmitting that model, as a prerequisite for making the advice make sense.

The slightly less short version

Notice a concept you wish to communicate.

Form phrases and sentences which accurately match the concept as it lives in your mind. (For some thoughts on how to gain skill at this, look here.)

Notice the specific ways in which those phrases and sentences will mislead your audience/reliably trigger predictable confusions. (I say “notice” to equivocate between “actively check for” and “effortlessly perceive”—in my experience, it’s the latter, but that comes from a combination of deliberately practicing the former and having been exposed to a large number of misunderstandings in the wild. For some thoughts on how to gain skill that is relevant to this, look here.)

Pre-empt the confusion by ruling out those misunderstandings which are some weighted combination of “most likely,” “most common,” “most serious,” and “most charged.” (For some responses to all of those objections that are no doubt coming to mind, read on.)

Words have meaning (but what is it?)

It’s a common trope in rationalist circles that arguments over semantics are boring/unproductive. Everyone seems to have gotten on the same page that it’s much more worthwhile to focus on the substance of what people intend to say than on what the words they used to say it ‘really’ mean.

I agree with this, to a point. If you and I are having a disagreement, and we discover that we were each confused about the other’s position because we were using words differently, and can quickly taboo those words and replace them with other words that remove the confusion, this is obviously the right thing to do.

But that’s if our goal is to resolve a present and ongoing disagreement. There can be other important goals, in which the historical record is not merely of historical interest.

For instance: it’s possible that one of us made an explicit promise to the other, and there was a double illusion of transparency—we both thought that the terms of the agreement were clear, but they were not, thanks to each of us using words differently. And then we both took actions according to our contradictory understandings, and bad things happened as a result, and now we’re trying to repair the damage and settle debts.

In this case, there’s not just the question of “what did we each mean at the time?” There’s also the question of “what was reasonable to conclude, at the time, given all of the context, including the norms of our shared culture?”

This is a more-or-less objective question. It’s not an unresolvable he-said-she-said, or a situation where everyone’s feelings and perspectives are equally valid.

(For a related and high-stakes example, consider the ongoing conflict over whether-or-not-and-to-what-degree the things Donald Trump said while president make him responsible for the various actions of his supporters. There are many places where Trump and Trump’s supporters use the defense “what he literally said was X,” and Trump’s detractors counter “X obviously means Y, what kind of fools do you take us for,” and in most cases this disagreement never resolves.)

I claim there is a very straightforward way to cut these Gordian knots, and it has consistently worked for me in both public and private contexts:

“Hey, so, looking back, your exact words were [X]. I claim that, if we had a hundred people in the relevant reference class evaluate [X] with the relevant context, more than seventy of them would interpret those words to be trying to convey something like [Y].”

This method has a lot to recommend it, over more common moves like “just declare authoritatively what words mean,” or “just leap straight to accusing your conversational partner of being disingenuous or manipulative.”

In particular, it’s checkable. In the roughly thirty times I’ve used this method since formalizing it in my head three years ago, there have been about four times that my partner has disagreed with me, and we’ve gone off and done a quick check around the office, or set up a poll on Facebook, or (in one case) done a Mechanical Turk survey. We never went all the way out to a hundred respondents, but in each of the four cases I can recall, the trends became pretty compelling pretty quickly.

(I was right in three cases and wrong in one.)

It also underscores (embodies?) a crucial fact about the meaning of words in practice:

Axiom: the meaning of a given word or phrase is a distribution.

Meaning is not a single fact, like “X means [rigorous definition Y],” no matter how much we might wish it were (and no matter how much it might be politically convenient to declare it so, in the middle of a disagreement).

Rather, it’s “X means Y to most people, but also has a tinge of Z, especially under circumstance A, and it’s occasionally used sarcastically to mean ¬Y, and also it means M to people over the age of 45,” and so on and so forth.

Alexis: “X clearly means Y!”

Blake: “No, X just means X!”

Cameron: “It means both—obviously, since you’re fighting about it—and the question of what either of you secretly meant inside your own head isn’t one we can conclusively resolve, but we can resolve the question of which interpretation was more reasonable at the time, which will let us all get past this tedious sniping and on to more actionable questions of who owes what for the misunderstanding and how to avoid similar misunderstandings in the future.”

Cameron is fun at parties.

(Cameron is actually fun at parties, at least according to me and my aesthetic and the kind of experience I want to have at parties; I know that “X is fun at parties” usually means that X is not fun at parties so I figured I’d clarify that my amusement at the above line is grounded in the fact that it’s unusually non-sarcastic.)

Visualizing the distribution

There’s a parallel here to standard rationalist reasoning around beliefs and evidence—it’s not that X is true so much as we have strong credence in X, and it’s not that X means Y so much as X is stronger evidence for Y than it is for ¬Y. In many ways, thinking of meaning as a distribution just is applying the standard rationalist lens to language and communication.

Even among rationalists, not everyone actually bothers to run the [imagine a crowd of relevant people and make a prediction about the range of their responses] move I described in the previous section. I run it because I’ve spent the last twenty years as a teacher and lecturer and writer and manager, and have had to put a lot of energy into adapting and reacting to things-landing-with-people-in-ways-I-didn’t-anticipate-or-intend. These days, I have something like a composite shoulder mob that’s always watching the sentences as they form in my mind, and responding with approval or confusion or outrage or whatever.

But I claim that most people could run such an algorithm, if they chose to. Most people have sufficient past experience with witnessing all sorts of conversations-gone-sideways, in all sorts of contexts. The data is there, stored in the same place you store all of your aggregated memories about how things work.

And while it’s fine to not want that subprocess running all the time, the way it does in my brain, I claim it’s quite useful to practice booting it up until it becomes a switch you are capable of flipping at will.

It’s especially useful because the generic modeling-the-audience move is step three in the process of effective, clear communication. If you can’t do it, you’ll have a hard time moving past “say the words that match what’s in your brain” and getting to “say the words that will cause the thing in their brain to match what’s in your brain.”

(Which is where the vast majority of would-be explainers lose their audiences.)

A toy example:

Imagine that I’m imagining a tree. A specific tree—one from the front yard of my childhood home in North Carolina.

If I want to get the thing in my head to appear in your head, a pretty good start would be to say “So, there’s this tree...”

At that point, two seconds in, the minds of my audience will already be in motion, and there will be a range of responses to having heard and understood those first four words.

...in fact, it’s likely that, if the audience is large enough, some of them will be activating concepts that the rest of us wouldn’t recognize as trees at all. Some of them might be imagining bushes, or Ents, or the act of smoking marijuana, or a Facebook group called “Tree,” or their family tree, or the impression of shade and rustling leaves, or a pink elephant, and so on and so forth.

I like to envision this range-of-possible-responses as something akin to a bell curve. If all I’ve communicated so far is the concept “tree,” then most people will be imagining some example of a tree (though many will be imagining very different trees) and then there will be smaller numbers of people at the tails imagining weirder and weirder things. It’s not actually a bell curve, in the sense that the-space-of-possible-responses is not really one-dimensional, but a one-dimensional graph is a way to roughly model the kind of thing that’s going on.

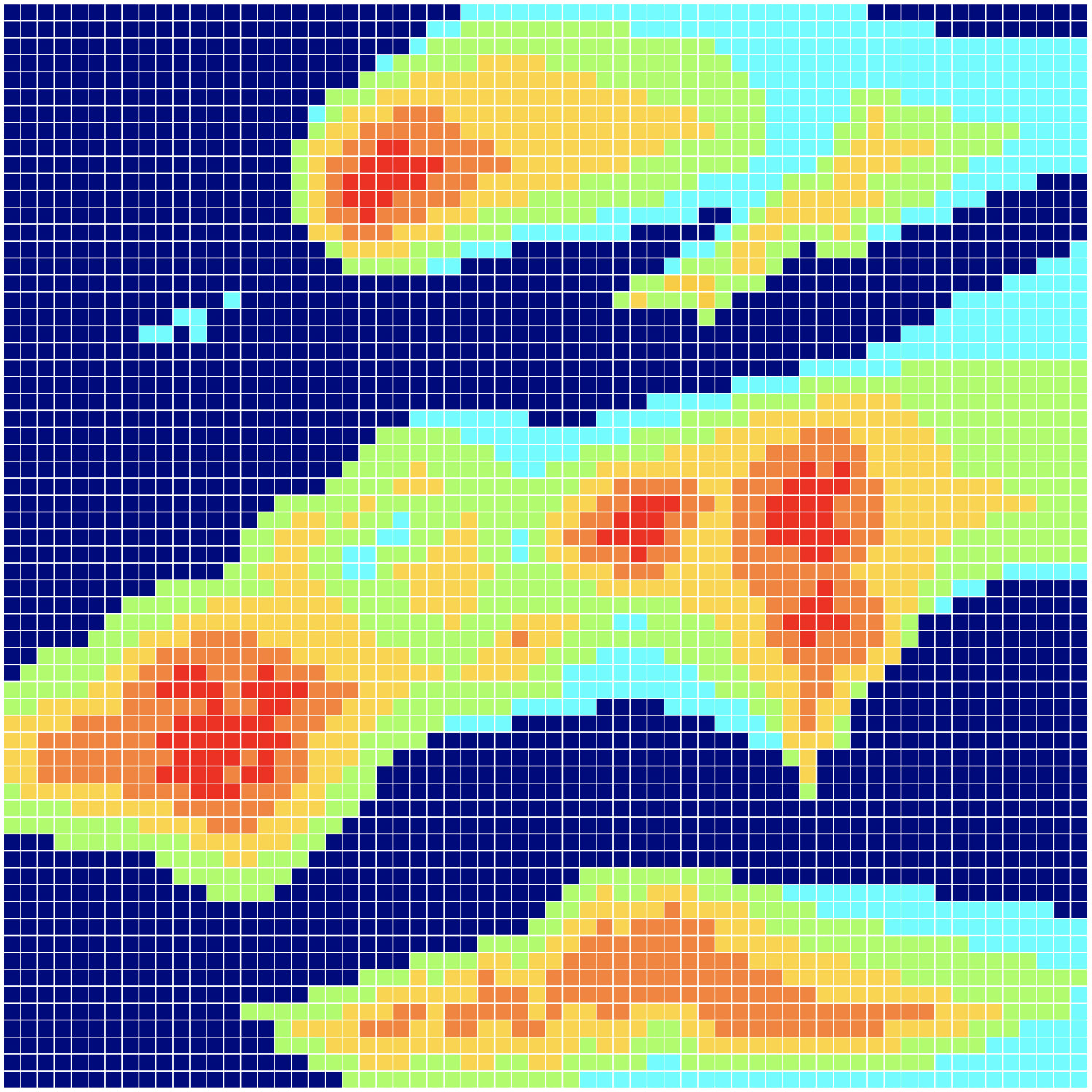

The X-axis denotes the range of responses. Everyone in a given column is imagining basically the same thing; the taller the column the more common that particular response. So perhaps one column contains all of the people imagining oak trees, and another column contains all of the people imagining pines:

Columns that are close to one another are close in concept-space; they would recognize each other as thinking of a pretty similar thing. For something like “tree,” there’s going to be a cluster in the middle that represents something like a normal response to the prompt—the sort of thing that everyone would agree is, in fact, a tree.

If there’s a cluster off to one side, as in this example, that might represent a second, more esoteric definition of the word (say, variants of the concept triggered in the minds of actual botanists), or maybe a niche subculture with unique associations (say, some group that uses trees as an important religious metaphor).

Of course, if we were to back out to a higher-dimensional perspective, we would likely see that there are actually a lot of distinct clusters that just appear to overlap, when we collapse everything down to a single axis:

… perhaps the highest peak here represents all of the people thinking of various deciduous leafy trees, and the second highest is the cluster of people thinking of various coniferous evergreen trees, and the third highest contains people thinking of tropical trees, and so on.

This more complicated multi-hump distribution is also the sort of thing one would expect to see if one were to mention a contentious topic with clear, not-very-overlapping camps, such as “gun rights” or “cancel culture.” If all you say is one such phrase, then there will tend to be distinct clusters of people around various interpretations and their baggage.

Shaping the distribution

But of course, one doesn’t usually stop after saying a single word or phrase. One can usually keep going.

“So, there’s this tree, a magnolia, that stands in the center of my yard in suburban North Carolina. It was the only living thing in the yard when we moved in, and it was sickly and scrawny and my dad wanted to tear it out. But my mom saved it, and over time it grew and got stronger and healthier and now it’s over ten meters tall and has the most beautiful white blossoms in the spring.”

There are two ways to conceptualize what’s happening, as I keep adding words.

The standard interpretation is that I am adding detail. There was a blank canvas in your mind, and at first it did not have anything at all, but now it has a stop-motion of a sickly magnolia tree growing into a magnificent, thriving one.

I claim the additive frame is misleading, though. True, I am occasionally adding new conceptual chunks to the picture, but what’s much more important, and what’s much more central to what’s going on, is what I’m taking away.

If you had a recording of me describing the tree, and you paused after the first four words and asked a bunch of people to write down what I was probably talking about, many of them would likely feel uncomfortable doing so. They would, if pressed, point out that while sure, yeah, they had their own private default mental association with the word “tree,” they had no reason to believe that the tree in their head matched the one in my head.

Many of them would say, in other words, that it’s too soon to tell. There are too many possibilities that fit the words I’ve given them so far.

Pause again after another couple of seconds, though, and they’d feel a lot more comfortable, because adding ”...a magnolia” rules out a lot of things. Pines, for instance, and oaks, and bushes, and red balloons.

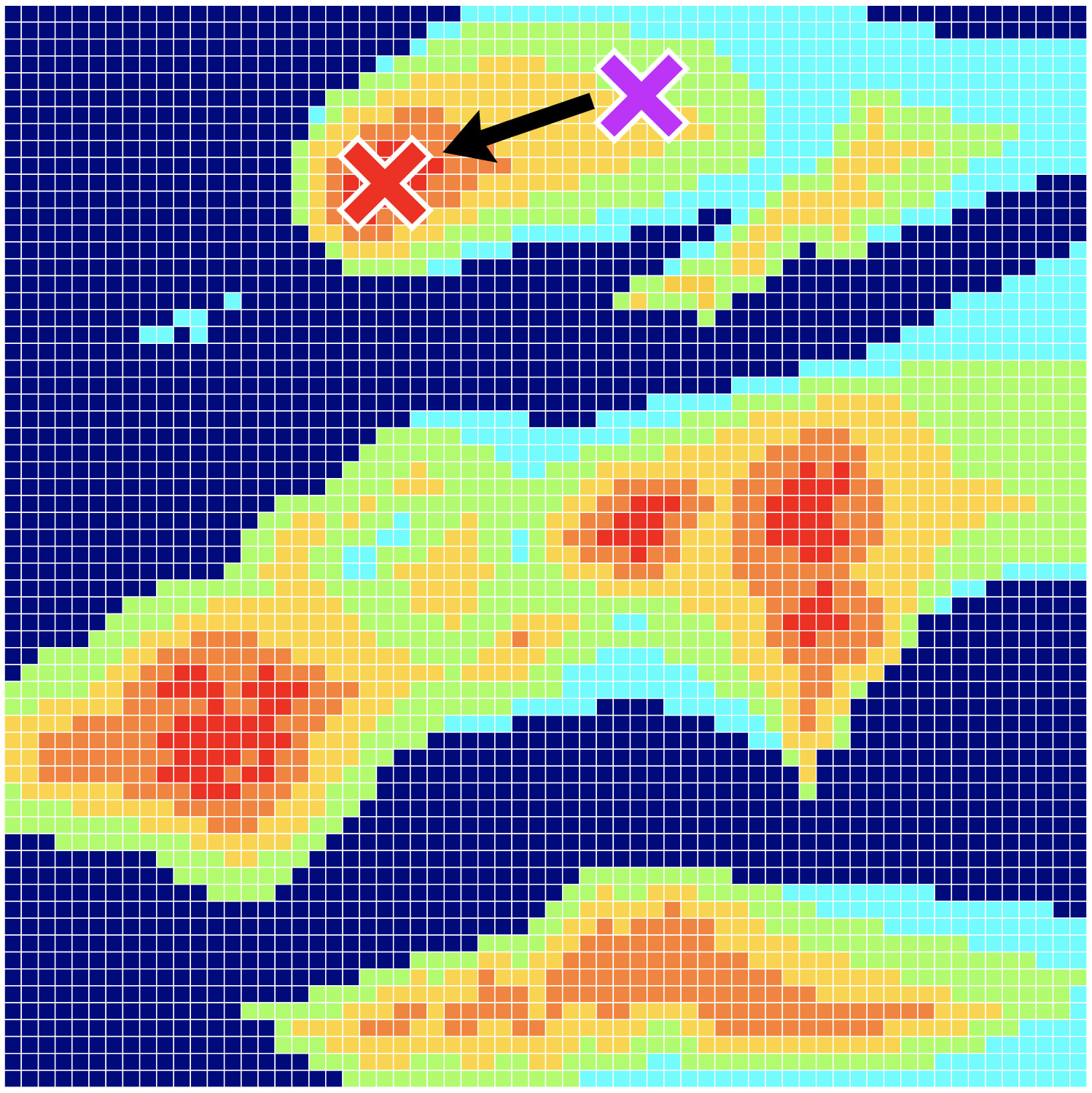

If we imagine that same pile of listeners that were previously in a roughly-bell-shaped distribution, adding the word “magnolia” reshuffles the distribution. It tightens it, shoving a bunch of people who were previously all over the place into a much narrower spread:

Each time I add another layer of detail to the description, I am narrowing the range of things-I-might-possibly-mean, taking huge swaths of options off the table. There are many more imaginings compatible with “tree” than with the more specific “magnolia tree,” and many more imaginings compatible with “magnolia tree” than with “magnolia tree that was once sickly and scrawny but is now healthy and more than ten meters tall.”

Note that the above paragraph of description relies upon the listener already having the concept “magnolia.” If I were trying to create that concept—to paint the picture of a magnolia using more basic language—I would need to take a very different tack. Instead, in the paragraph above, what I’m doing is selecting “magnolia” out of a larger pile of possible things-you-might-imagine. I’m helping the listener zero in on the concept I want them to engage with.

And the result of this progressive narrowing of the picture is that, by the time I reach the end of my description, most of the people who started out imagining palm trees, or family trees, or who misheard me and thought I said “mystery,” have now updated toward something much closer to the thing in my head that I wanted to transmit.

Backing out from the toy example, to more general principles:

No utterance will be ideally specific. No utterance will result in every listener having the same mental reaction.

But by using a combination of utterances, you can specify the location of the-thing-you-want-to-say in concept space to a more or less arbitrary degree.

“I’m thinking of a rock, but more specifically a gray rock, but more specifically a rock with a kind of mottled, spotted texture, but more specifically one that’s about the size of a washing machine, but more specifically one that’s sitting on a hillside, but more specifically one that’s sitting half embedded in a hillside, but more specifically a hillside that’s mostly mud and a few scruffy trees and the rock is stained with bird poop and scattered with twigs and berries and the sun is shining so it’s warm to the touch and it’s located in southern California—”

Building a meaning moat

When the topic at hand is trees, it’s fairly easy to get people to change their position on the bell curve. Most people don’t have strong feelings about trees, or sticky tribal preconceptions, and therefore they will tend to let you do things like iterate, or add nuance, or start over and try again.

There aren’t really attractors in the set of tree concepts—particular points in concept-space that tinge and overshadow everything near them, making nuance difficult. Not strong ones, at least.

This is much less true for topics like politics, or religion, or gender/sexuality/ relationships. Topics where there are high stakes—where the standard positions are more or less known, and audiences have powerful intuitions about the kinds of people who take those positions.

A few hundred years ago, the people that were trying to cobble together a new nation had incompatible opinions about some basic moral principles.

Their ancestors were, in part, people who’d had to flee an entire hemisphere because the disagreement there was so vehement and virulent that you couldn’t even propose the possibility that debate itself might be valid or called-for.

And so, each of them holding some of their colleagues’ opinions in contempt, they nevertheless saw enough nuance and uncertainty in their own individual cultures that they recognized, and enshrined-as-instrumentally-critical, the value and legitimacy of disagreement and debate.

And so various people were able to live shoulder-to-shoulder despite often-extreme disagreement, on the twin principles of “live and let live” and “it’s possible my own culture’s answers might not be universally correct or applicable.”

But at some point, some people came up with the clever argument that nuance itself was being used by Very Bad People, who were leveraging it as wiggle room to get away with doing Very Bad Things.

This was, in fact, incontrovertibly true, in some cases.

That allowed them—some of them, in some places—to use their argument to attack the idea that nuance itself was a valid concept to recognize, or a thing worth having and defending, and to successfully paint anyone who relied upon or defended nuance as deliberately enabling Very Bad People.

And since the difference between “deliberately enabling a Very Bad Person” and “arguing for a system that sometimes enables them as an unavoidable cost that is nevertheless worth paying” is itself nuance, and since the difference between incidentally enabling a Very Bad Person and being a Very Bad Person is nuance, too...

In some domains, there are strong pressures driving a kind of rounding-off and oversimplification, in which everything sufficiently close to X sounds like X, and is treated as if it is X, which often pushes people in favor of not-quite-X straight into the X camp, which further accelerates the process.

(Related.)

It’s one thing to nudge people from “tree” to the more specific “magnolia,” even if your clumsy first pass had them thinking you meant “mangroves.” It’s another thing entirely to start out with a few sentences that trigger the schema “eugenicist” or “racist” or “rape apologist,” and then get your listeners to abandon that initial impression, and update to believing that you meant something else all along.

This is why this essay strongly encourages people to model the audience’s likely reactions up front, rather than simply trying things and seeing what comes back. Attractors are hard to escape, and if you have no choice but to tread near one, there’s a huge difference between:

Okay, before I even start, I want to clearly differentiate my belief D from A, B, and C, each of which I disagree with for [reason, reason, reason].

and

Whoa, whoa, wait, I didn’t mean A, B, or C! I’m trying to say D, which is different! For [reasons which now sound like frantic backpedaling and an attempt to escape judgment]!

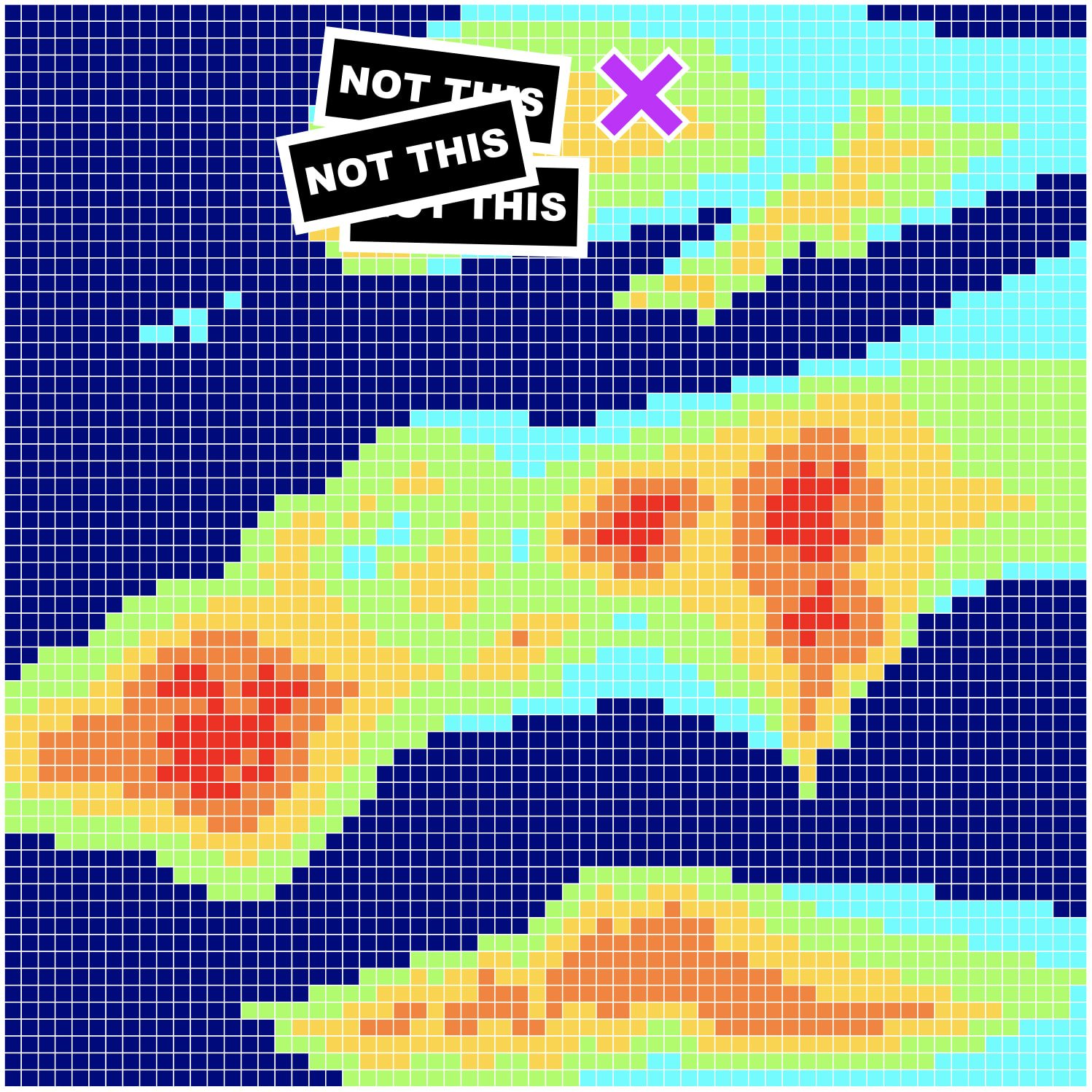

The key tool I’m advocating here is something I’m calling a meaning moat.

(As in, “I’m worried people will misinterpret this part of the email; we need to put a meaning moat in between our proposal and [nearest objectionable strawman].”)

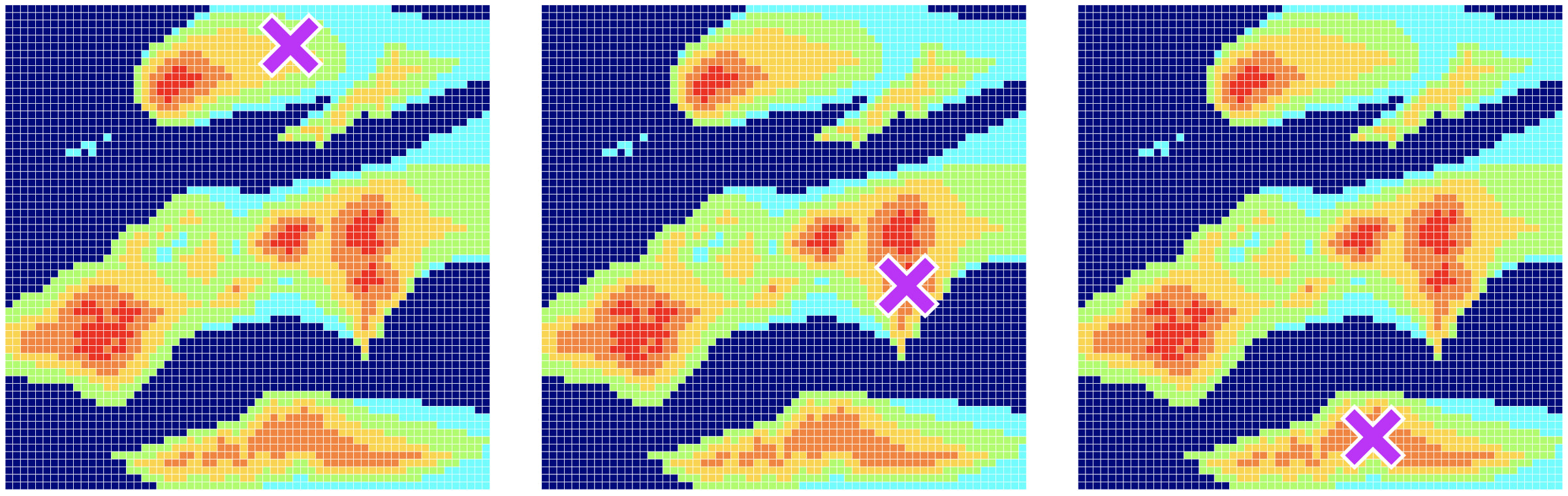

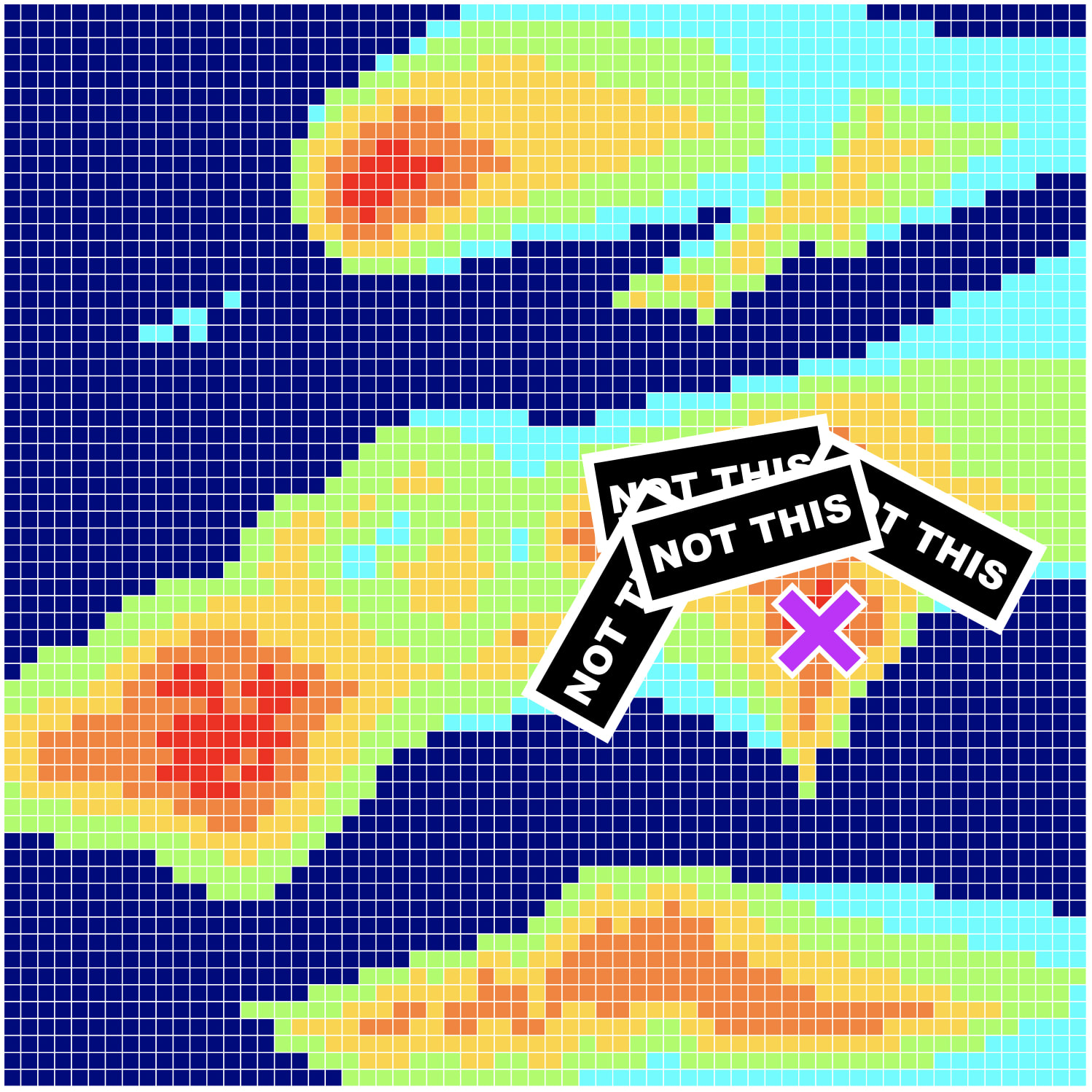

Imagine one of the bell curves from before, but “viewed from above,” such that the range of responses are laid out in two-dimensional space. Someone is planning on saying [a thing], and a lot of people will hear it, and we’re going to map out the distribution of their probable interpretations.

Each square above represents a specific possible mental state, which would be adopted in response to whatever-it-is that our speaker intends to say. Squares are distinct(ish) audience interpretations.

(I’m deliberately not using a specific example in this section because I believe that any such example will split my readers in exactly the way I want to talk about sort of neutrally and dispassionately, and I don’t want the specifics to distract from a discussion of the general case. But if you absolutely cannot move forward without something concrete, feel free to imagine that what’s depicted is the range of reactions to someone who starts off by saying “people should be nicer.” That is, the above map represents the space of what a bunch of individual listeners would assume that the phrase “people should be nicer” means—the baggage that each of them would bring to the table upon hearing those words.)

As with the side-view of the bell curve above, adjacent spots are similar interpretations; for this map we’ve only got two axes so there are only two gradients being represented.

Navy squares means “no one, or very few people, would hold this particular interpretation after hearing [thing].”

Red squares mean “very many people would hold this interpretation after hearing [thing].”

The number of clusters in the map is more or less arbitrary, depending on how tight a grouping has to be before you call it a “cluster.” But there are at least three, and arguably as many as eight. This would correspond to there being somewhere between three and eight fairly distinct interpretations of whatever was just said. So, if it was a single word, that means that word has at least three common definitions. If it was a phrase, that means that the phrase could be taken in at least three substantially different ways (e.g. interpreted as having been sincere, sarcastic, or naive). And if it was a charged or political statement, that means there are probably at least three factions with three different takes on this issue.

I claim that something-like-this-map accurately represents what actually happens whenever anyone says approximately anything. There is always a range of interpretation, and if there are enough people in the audience, there will be both substantial overlap and substantial disoverlap in those interpretations.

(I’ve touched on this claim before.)

And now, having anticipated this particular range of responses, most of which will not match the concept within the speaker’s mind, it’s up to the speaker to rule out everything else.

(Or, more accurately, since one can’t literally rule out everything else, to rule out the most likely misunderstandings, in order of importance/threat.)

What is our speaker actually trying to convey?

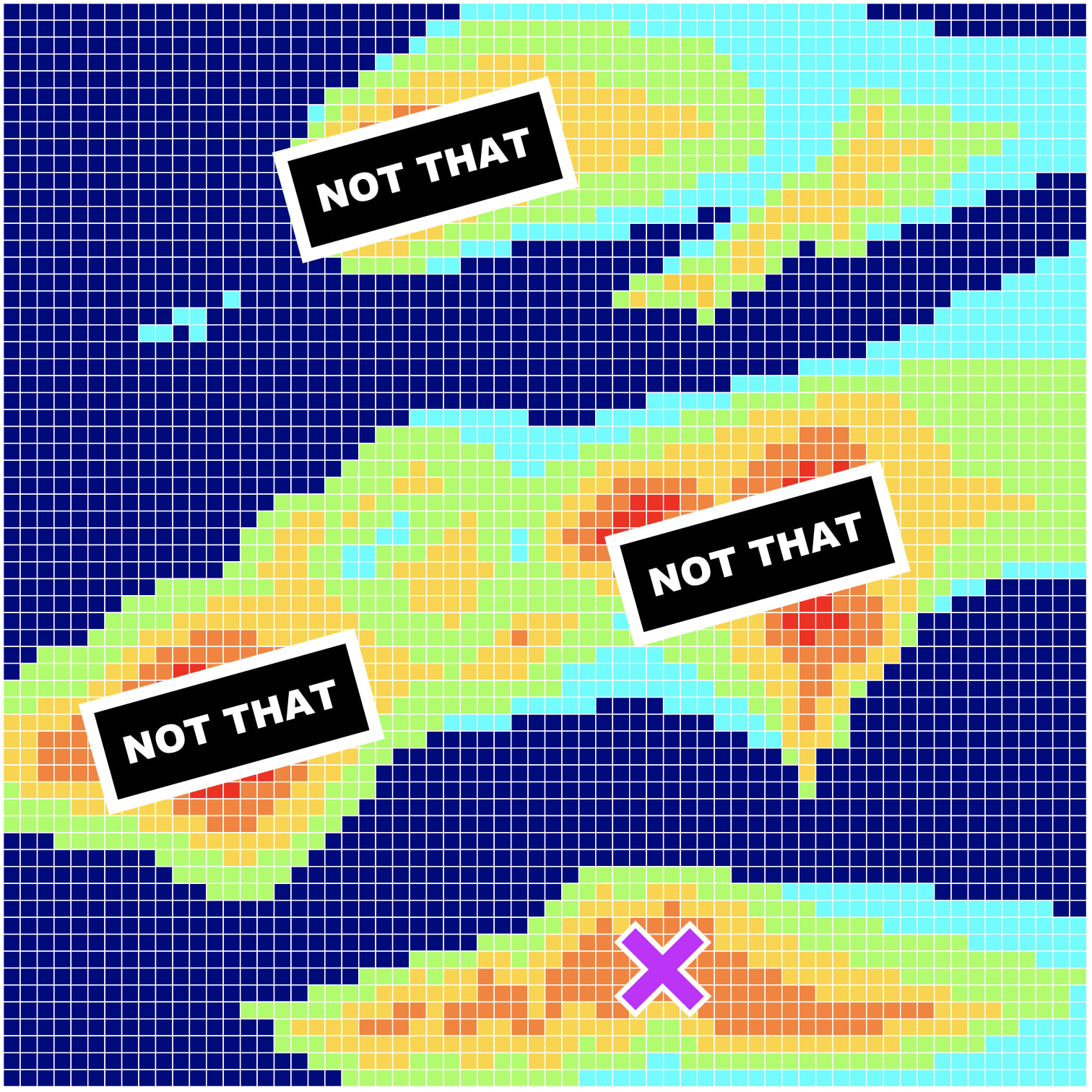

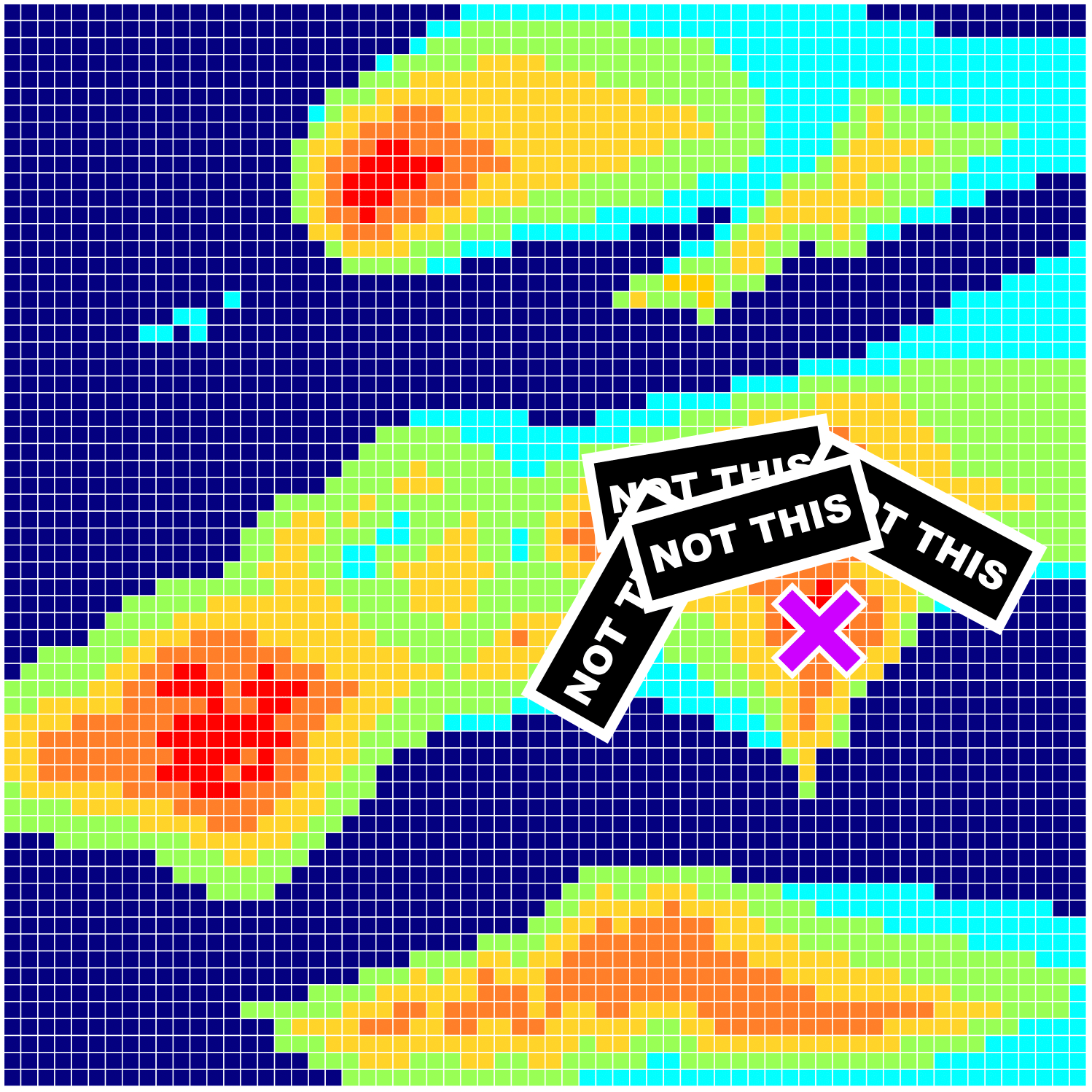

Let’s imagine three different cases:

In the first case, the concept that lives in our speaker’s mind is near to the upper cluster, but pretty distinct from it.

In the second case, the speaker means to communicate something that is its own cluster, but it’s also perilously close to two other nearby ideas that the speaker does not intend.

In the third case, the speaker means something near the center of a not-very-tightly-defined memeplex.

(We could, of course, explore all sorts of other possibilities, including possibilities on very different maps, but these three should be enough to highlight the general principle.)

(I’m going to assume that the speaker is aware of these other, nearby interpretations; things get much harder if you’re feeling your way forward blindly.)

(I’m also going to assume that the speaker is not trying to say something out in the blue, because if so, their first draft of an opening statement was so misleading in expectation, and set them up for such an uphill battle, that they may as well give up and start over.)

In each of these three cases, there are different misconceptions threatening to take over. Our speaker has different threats to defend against, and should employ a different strategy in response to each one.

In the first case, the biggest risk is that the speaker will be misconstrued as intending [the nearby commonly understood thing]. People will listen to the first dozen words, recognize some characteristic hallmarks of the nearby position, and (implicitly, unintentionally) conclude that they know exactly what the speaker is talking about, and it’s [that thing]:

This will be particularly true of people who initially thought that the speaker meant [things represented by the lower patches of red and orange]. As soon as those people realize “oh, they’re not expressing the viewpoint I originally thought they were,” many of them will leap straight to the central, typical position of the upper patch.

People usually do not abandon their whole conceptual framework all at once; if I at first thought you were pointing at a pen on my desk, and then realized that you weren’t, I’ll likely next conclude that you were pointing at the cup on my desk, rather than concluding that you were doing an isometric bodyweight exercise. If there are a few common interpretations of your point, and it wasn’t the first one, people will quite reasonably tend to think “oh, it was the second one, then.”

So in the first case, anticipating this whole dynamic, the speaker should build a meaning moat that unambiguously separates their point from that nearby thing. They should rule it out; put substantial effort into demonstrating that [that thing] cannot possibly be what they mean. [That thing] represents the most likely misunderstanding, and is therefore the highest priority for them to distinguish their true position from.

(One important and melancholy truth is that you are never fully pinning down a concept in even a single listener’s mind, let alone a diverse group of listeners. You’re always, ultimately, drawing some boundary and saying “the thing I’m talking about is inside that boundary.” The question is just how tight you need the boundary to be—whether greater precision is worth the greater effort required to achieve it, and how much acceptable wiggle room there is for the other person to be thinking something a little different from what you intended without that meaningfully impacting the goals of the interaction. Hence, the metaphor of a moat rather than something like precise coordinates.)

In the second case, there’s a similar dynamic, except it’s even more urgent, since the misunderstandings are closer. It will likely take even more words and even more careful attention to avoid coming off as trying to say one of those other very nearby things; it often won’t suffice to just say “by the way, not [that].”

For instance, suppose there’s a policy recommendation B, which members of group X often support, for reasons Y and Z.

If you disagree with group X, and think reasons Y and Z are bad or invalid, yet nevertheless support B for reasons M and N, you’ll often have to do a lot of work to distinguish yourself from group X. You’ll often have to carefully model Y and Z, and compellingly show (not just declare) that they are meaningfully distinct from M and N. And if the policy debate is contentious enough, or group X abhorrent enough, you may even need to spend some time passing the ITT of someone who is suspicious that anyone who supports B must be X, or that support of B is tantamount to endorsement of the goals of X.

(A hidden axiom here is that people believe the things they believe for reasons. If you anticipate being rounded off to some horrible thing, that’s probably both because a) you are actually at risk of being rounded off to it, and b) the people doing the rounding are doing the rounding because your concept is genuinely hard to distinguish from the horrible thing, in practice. Which means that you can’t reliably/successfully distinguish it by just saying that it’s different—you have to make the difference clear, visceral, and undeniable. For more in this vein, look into decoupling vs. contextualizing norms.)

In other words, not “I’m not racist, but B” so much as “no, you’re not crazy, here’s why B might genuinely appear racist, and here’s why racists might like or advocate for B, I agree those things are true and problematic. But for what it’s worth, here’s a list of all the things those racists are wrong about, and here’s why I agree with you that those racists are terrible, and here’s a list of all the good things that are in conflict with B, and here’s my best attempt to weigh them all up, and here are my concrete reasons why I still think B even after taking all of that into account, and here’s why and how I think it’s possible to support B without effectively lending legitimacy to racists, and here are a couple of examples of things I might observe that would cause me to believe I was wrong about all this, and here’s some up-front validation that you’ve probably heard this all before and I don’t expect you to just take my word for any of this but please at least give me a chance to prove that I actually have a principled stance, here.”

The latter is what I mean by “meaning moat.” The former is just a thin layer of paint on the ground.

Interestingly, the speaker in the third case can get away with putting forth much less effort. There’s no major nearby attractor threatening to overshadow the point they wish to make, and the other available preconceptions are already distant enough that there likely won’t be a serious burden of suspicion to overcome in the first place. There’s a good chance that they actually will be able to simply declare “not that,” and be believed.

Axiom: the amount of work required to effectively build a meaning moat between your point and nearby attractors is proportional to a) their closeness, and b) their salience.

The more similar your point is to a preconception the audience holds, the harder you’ll have to work to get them to understand the distinction. And the stronger they feel about the preconception, the harder it will be to get them to have a different feeling about the thing you’re trying to say (which is why it’s best to start early, before the preconception has had a chance to take hold).

Three failures (a concrete example)

Recently-as-of-the-time-of-this-writing, there was heated discussion on LessWrong about the history of a research organization in the Bay Area, and the impact it had on its members, many of whom lived on-site under fairly unusual conditions.

Without digging into that broader issue at all, the following chain of three comments in that discussion struck me as an excellent example of three people in a row not doing sufficient work to rule out what they did not mean.

The first comment came from a member of the organization being discussed:

Managing the potential for abuses by those in positions of power is very important to us. If anyone is aware of harms or abuses that have taken place involving staff at [organization], please email me, in confidence, at [name]@[organization] or [name]@gmail.com.

In response:

Bullshit. This is not how you prevent abuse of power. This is how you cover it up.

And in response to that (from a third party):

Have you even read the default comment guidelines? Hint: they’re right below where you’re typing.

For your reference:

Default comment guidelines:

Aim to explain, not persuade

Try to offer concrete models and predictions

If you disagree, try getting curious about what your partner is thinking

Don’t be afraid to say ‘oops’ and change your mind

In my culture, none of these three comments passes muster, although only one of them was voted into negative territory in the actual discussion.

The first speaker was (clearly and credibly, in my opinion) concerned with preventing harm. They felt that the problems under discussion had partially been caused by a lack of outreach/insufficient lines of communication, and were trying to say “there are people here who care, and who are listening, and I am one of them.”

(Their comment was substantially longer than what’s quoted here, and contained a lot of other information supporting this interpretation.)

But even in the longer, complete comment, they notably failed to distinguish their offer of help from a trap, especially given the atmosphere of suspicion that was dominant at the time. Had they paused to say to themselves “Imagine I posted this comment as-is, and it made things worse. What happened?” they would almost certainly have noticed that there was an adversarial interpretation, and made some kind of edit in pre-emptive response.

(Perhaps by validating the suspicion, and providing an alternate, third-party route by which people could register concerns, which both solves the problem in the world where they’re a bad actor and credibly signals that they are not a bad actor.)

The second speaker … well, the second speaker probably did say exactly what they meant, connotation and implication and all. But if I imagine a better version of the second speaker—one who is less overconfident and more capable of doing something like split and commit—and I try to express the same concern from that perspective, it would go something like:

“Okay, so, I understand that you’re probably just trying to help, and that you genuinely want to hear people’s stories so that you can get to work on making things better. But like. You get how this sounds, right? You get how, if I’m someone who’s been systematically and cleverly abused by [organization], that asking me to email the higher-ups of [organization] directly is not a realistic solution. At best, this comment is tone-deaf; at worst, it’s what someone would do if they were trying to look good while participating in a cover-up.”

The key here being to build a meaning moat between “this is compatible with you being a bad actor” and “you are a bad actor.” The actual user in question likely believed that the first comment was sufficient evidence to conclude that the first speaker is a bad actor. I, in their shoes, would not be so confident, and so would want to distinguish my pushback from an accusation.

The third speaker’s mistake, in my opinion, lay in failing to distinguish pushback on the form of the second speaker’s comment from pushback on the content. They were heavily downvoted—mostly, I predict, because people felt strong resonance with the second speaker’s perspective, and found the third speaker’s objection to be tangential and irrelevant.

If I myself had wanted to push back on the aggressive, adversarial tone of the second comment, I would have been careful to show that I was not pushing back on the core complaint (that there really was something lacking in the first comment). I would have tried, in my reply, to show how one could have lodged the core complaint while remaining within the comment guidelines, and possibly said a little bit about why those guidelines are important, especially when the stakes are high.

(And I would have tried not to say something snarky while in the middle of policing someone else’s tone.)

All of that takes work. And perhaps, in that specific example, the work wasn’t worth it.

But there are many, many times when I see people assuming that the work won’t be worth it, and ultimately being compelled to spend way more effort trying to course-correct, after everything has gone horribly (and predictably) wrong.

The central motivating insight, restated, is that there’s a big difference between whether a given phrasing is a good match for what’s in your head, and whether that phrasing will have the effect you want it to have, in other people. Whether it will create, in those other people’s heads, the same conceptual object that exists in yours.

A lot of people wish pretty hard that those two categories were identical, but they are not. In many cases, they barely even overlap. The more it matters that you get it right, the more (I claim) you should put concrete effort into envisioning the specific ways it will go wrong, and heading them off at the pass.

And then, of course, be ready for things to go wrong anyway.

Author’s note: These days, my thoughts go onto my substack instead of onto LessWrong. Everything I write becomes free after a week or so, but it’s only paid subscriptions that make it possible for me to write. If you found a coffee’s worth of value in this or any of my other work, please consider signing up to support me; every bill I can pay with writing is a bill I don’t have to pay by doing other stuff instead. I also accept and greatly appreciate one-time donations of any size.

- Simulators by (2 Sep 2022 12:45 UTC; 672 points)

- Sazen by (21 Dec 2022 7:54 UTC; 295 points)

- Basics of Rationalist Discourse by (27 Jan 2023 2:40 UTC; 283 points)

- 's comment on Moderation notes re: recent Said/Duncan threads by (14 Apr 2023 18:32 UTC; 75 points)

- Prizes for the 2021 Review by (10 Feb 2023 19:47 UTC; 69 points)

- The possible shared Craft of deliberate Lexicogenesis by (20 May 2023 5:56 UTC; 66 points)

- Voting Results for the 2021 Review by (1 Feb 2023 8:02 UTC; 66 points)

- At odds with the unavoidable meta-message by (10 Oct 2025 0:13 UTC; 58 points)

- 's comment on An epistemic advantage of working as a moderate by (29 Aug 2025 15:27 UTC; 36 points)

- 's comment on Buck’s Shortform by (9 Oct 2025 21:49 UTC; 31 points)

- 's comment on Speaking of Stag Hunts by (7 Nov 2021 20:19 UTC; 27 points)

- 's comment on Speaking of Stag Hunts by (8 Nov 2021 1:50 UTC; 10 points)

- 's comment on LW Team is adjusting moderation policy by (6 Apr 2023 20:33 UTC; 10 points)

- 's comment on Speaking of Stag Hunts by (7 Nov 2021 22:25 UTC; 9 points)

- 's comment on Epistemic Legibility by (11 Feb 2022 22:10 UTC; 9 points)

- 's comment on [Book Review] “The Bell Curve” by Charles Murray by (3 Nov 2021 0:29 UTC; 9 points)

- 's comment on Why defensive writing is bad for community epistemics by (EA Forum; 10 Oct 2022 23:16 UTC; 8 points)

- 's comment on Speaking of Stag Hunts by (6 Nov 2021 14:23 UTC; 8 points)

- 's comment on Speaking of Stag Hunts by (9 Nov 2021 3:33 UTC; 6 points)

- 's comment on Basics of Rationalist Discourse by (31 Jan 2023 20:53 UTC; 6 points)

- 's comment on [SEE NEW EDITS] No, *You* Need to Write Clearer by (30 Apr 2023 17:00 UTC; 6 points)

- 's comment on [anonymous]’s sketchpad by (13 Nov 2021 18:45 UTC; 5 points)

- 's comment on Murphyjitsu: an Inner Simulator algorithm by (5 Jul 2022 16:12 UTC; 5 points)

- 's comment on Repairing the Effort Asymmetry by (8 Apr 2023 6:10 UTC; 4 points)

- 's comment on Policy discussions follow strong contextualizing norms by (2 Apr 2023 5:34 UTC; 4 points)

- 's comment on Our mental building blocks are more different than I thought by (15 Jun 2022 16:33 UTC; 3 points)

- 's comment on Benito’s Shortform Feed by (27 Feb 2024 16:53 UTC; 2 points)

- 's comment on “Rationalist Discourse” Is Like “Physicist Motors” by (10 Mar 2023 6:00 UTC; 2 points)

- 's comment on Murphyjitsu: an Inner Simulator algorithm by (6 Jul 2022 12:33 UTC; 1 point)

- 's comment on Write a Thousand Roads to Rome by (27 Dec 2021 2:01 UTC; 1 point)

- 's comment on lsusr’s Shortform by (21 Jun 2023 4:25 UTC; 1 point)

- 's comment on Monks of Magnitude by (27 May 2022 18:58 UTC; 1 point)

- 's comment on [Book Review] “The Bell Curve” by Charles Murray by (3 Nov 2021 2:01 UTC; -2 points)

One of the things I like about this post the most, is it shows how much careful work is required to communicate. It’s not a trick, it’s not just being better than other people, it’s simple, understandable, and hard work.

I think all the diagrams are very helpful, and really slow down and zoom in on the goal of nailing down an interpretation of your words and succeeding at communicating.

There’s a very related concept (almost so obvious that you could say it’s contained in the post) of finding common ground, where, in negotiation/conflict/disagreement, you can rule out things that neither of you want or believe and thus find common ground. “I believe people should be nicer” “While I think that’s a nice thing to say, I think you’re pushing against some other important norm, perhaps of being direct with people or providing criticism” “Sorry, let me be clear; I in no way wish to lower the current levels of criticism, directness, or even levels of upset people are getting, and I think we’re on the same page on that; I’m interested in people increasing their thoughtfulness in other ways” “Ah, thanks, I see we have common ground on that issue, so I feel less threatened by this disagreement. I’m not sure I agree yet, but let’s see about this.” I think the post is helpful for seeing this.

I disagree with the application to an example on LessWrong, as is not uncommon I tend to think the theory in Duncan’s post is true and very well explained, and then thoroughly disagree with its application to a recent political situation. I don’t think that is much reason to devalue the post though.

This is a post I think about explicitly on occasion, I think it’s pretty important for communication, and I’m giving the post a +4.

(Meta: this is not a great review on my part, but I am leaning on the side of sharing my perspective for why I’m voting. I wish I had more time to write great reviews that I more confidently expected to help others think about the posts.)

This is a great post that exemplifies what it is conveying quite well. I have found it very useful when talking with people and trying to understand why I am having trouble explaining or understanding something.