It has been a subject of much recent internet discourse that the kids are not okay. By all reports, the kids very much seem to be not all right.

Suicide attempts are up. Depressive episodes are way up. The general vibes and zeitgeist one gets (or at least that I get) from young people are super negative. From what I can tell, they see a world continuously getting worse along numerous fronts, without an ability to imagine a positive future for the world, and without much hope for a positive future for themselves.

Should we blame the climate? Should we blame the phones? Or a mind virus turning them to drones? Heck, no! Or at least, not so fast.

Let’s first lay out the evidence and the suspects.1

Then, actually, yes. Spoiler alert, I’m going to blame the phones and social media.

After that, I’ll briefly discuss what might be done about it.

Suicide Rates

The suicide numbers alone would seem at first to make it very very clear how not all right the kids are.

Washington Post reports, in an exercise in bounded distrust:

Nearly 1 in 3 high school girls reported in 2021 that they seriously considered suicide — up nearly 60 percent from a decade ago — according to new findings from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Almost 15 percent of teen girls said they were forced to have sex, an increase of 27 percent over two years and the first increase since the CDC began tracking it.

…

Thirteen percent [of girls] had attempted suicide during the past year, compared to 7 percent of boys.

One child in ten attempted suicide this past year, and it is steadily increasing? Yikes.

There is a big gender gap here, but as many of you already suspect because the pattern is not new, it is not what you would think from the above.

In the U.S, male adolescents die by suicide at a rate five times greater than that of female adolescents, although suicide attempts by females are three times as frequent as those by males. A possible reason for this is the method of attempted suicide for males is typically that of firearm use, with a 78–90% chance of fatality. Females are more likely to try a different method, such as ingesting poison.[8] Females have more parasuicides. This includes using different methods, such as drug overdose, which are usually less effective.

I am going to go ahead and say that if males die five times as often from suicide, that seems more important than the number of attempts. It is kind of stunning, or at least it should be, to have five boys die for every girl that dies, and for newspapers and experts to make it sound like girls have it worse here. Very big ‘women have always been the primary victims of war. Women lose their husbands, their fathers, their sons in combat’ (actual 1998 quote from Hillary Clinton) energy.

The conflation of suicide rates with forced sex here seems at best highly misleading. The sexual frequency number is rather obviously a reflection of two years where people were doing rather a lot of social distancing. With the end of that, essentially anything social is going to go up in frequency, whether it is good, bad or horrifying – only a 27 percent increase seems well within the range one would expect from that. Given all the other trends in the world, it would be very surprising to me if the rates of girls being subjected to forced sex (for any plausible fixed definition of that) were not continuing to decline.

That implies that in the past, things on such fronts were no-good, horribly terrible, and most of it remained hidden. I do indeed believe exactly this.

Also, can we zoom out a bit? On a historical graph, the suicide rate does not look all that high (scale is suicides per 100,000 children, per year)?

The kids are not okay. The kids in the 1990s were, by some of these graphs, even more not okay. The kids in between were also not okay. It’s not like 14% is an acceptable number of kids seriously considering suicide in a given year, or 7% an acceptable rate of them attempting it. But those kids, by these measures, were less not okay.

CDC Risk Study

We also know that the rate of major depressive episodes among US adolescents increased by more than 52 percent between 2005 and 2017. I do think some of that is changing norms on what we call such an episode. I doubt that is all (or more than all) of it. That problem still seems sufficient to make farther-back comparisons not so meaningful, and make me want to fall back on suicides, similar to the case count vs. death count question in measuring Covid.

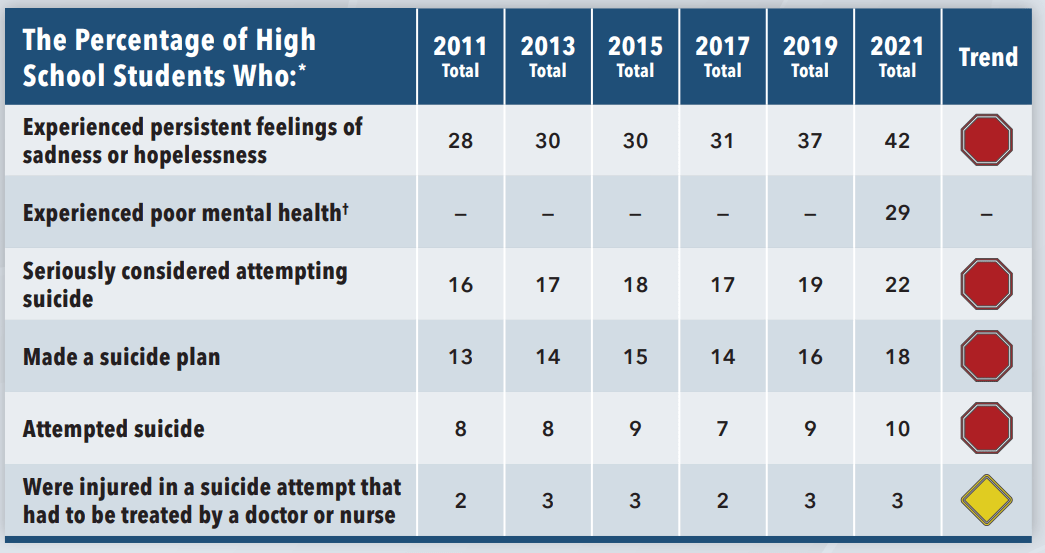

Here is the CDC study of youth risk behavior.

They are happy to report several things. Adolescents are engaging in less ‘risky sexual behavior,’ which means less sexual behavior period, both at all and with four or more partners. There is less substance (alcohol, marijuana, illicit drug, misused prescription drug) use.

(Rough math aside: In case anyone was wondering, yes, sexual contacts and alcohol use go together. If 30% of students have had sex and they are 41% likely to be drinking, and overall rate is 23%, that means only 13% of virgins are drinking, over a 3:1 ratio. For illicit drugs, 25% vs. 7.4%. And for marijuana, this it’s 34% vs. 8.3%, over 4:1, so looks like hard drugs are bad even on their own terms.)

Overall: So less fun. Sounds depressing. Less sexual activity is flat out called ‘improvement’ by the CDC. I am going to come out and say that the optimal amount of teenage sexual activity, and the optimal amount of teenage substance use, are importantly not zero.

They also talk glowingly about ‘parental monitoring,’ defined as parents or other adults in their family knowing where students are going and who they are with, as ‘another key protective factor for adolescent health and well-being.’ While I certainly would agree with the correlation with short term physical safety, and that this leads to less sexual activity and substance use, I would centrally say that considering this a key protective factor is one of the prime suspects for reasons kids are depressed so often.

On the plus side, there was also less bullying.

They are less happy to report worse overall mental health, more suicidal thoughts and more suicidal behaviors, as already noted. There is less condom use, less STD testing and less HIV testing, which is what rational people would do given less sexual promiscuity and improved treatments available for HIV.

(On another note, this below has to be the weirdest stat I’ve seen, I keep trying to figure out what it could mean and coming up short.)

If you look at the above graph, you’ll notice that HIV testing is not declining once you control for rates of sexual activity. The decline in condom use is entirely explained by the decline in multiple sex partners combined with selecting responsible teens out of the dating pool. If we had access to ‘the crosstabs’ we could check if this is indeed what is happening.

They also observe a rise in ‘experiences of violence.’ When I saw that I noted I was outright calling BS on any real effect. To the extent that ‘experiences of violence’ are rising, it is about what people are told to report experiencing changing, not about any increase in real physical violence. Then I found the actual stats on page 46:

I mean that’s some bounded distrust right there. Is this an increase in violence? The only substantial increase here is not going to school because of safety concerns. I am happy to report that safety concerns are not violence. Actual safety concerns in a school surround bullying, which is down (and I’d heavily bet is down in severity too). What do we do about that? I mean, same as we always have, and hint it isn’t letting them miss school. We force students who are being beaten up by other students into close proximity with their bullies at the barrel of a gun, of course. What else would we do?

Also, seriously, no increase in electronic bullying since the introduction of the smart phone, are you kidding me? How is this even real? How did we do it? Huge if true.

Also I will state that ‘did not go to school because of safety concerns’ did not change between 2019 and 2021 and let that float around in everyone’s head for a bit.

There are a bunch of other ‘are you seriously saying this trend went this way during the pandemic?’ stats and I will spare you the rest of them.

On to their depression stats, which match other sources.

I am curious about the 13% or more who experienced persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness without poor mental health. If I was feeling persistently sad or hopeless and someone asked me for the quality of my mental health, and I had the energy to reply, I would reply ‘poor, thanks for asking.’

Strangely, they list suicide considerations, plans, attempts and injuries, but do not list stats on actual suicides.

Objectively Worse?

This New York Magazine article says that ‘No, Teen Suicide Isn’t Rising Because Life Got Objectively Worse.’ It does confirm that the lived experience of teens seems to have gotten worse, at least in terms of their mental health.

Life isn’t ‘objectively worse,’ in this view, because the economy has improved as has our social safety net. Our treatment of many groups has dramatically improved. If you are entering the labor force today, goes the argument, you can expect to earn a much higher ‘standard of living’ than your predecessors in the 1950s. Suspicion is pointed towards our phones and social media.

I would suggest this misunderstands what it means for things to be ‘objectively worse.’

Economically one should emphasize the ability to purchase a socially acceptable goods basket that enables the important aspects of life, more than worrying about the measured quality of its components.

Similarly, I would assert that the existence of social media can absolutely make things ‘objectively’ worse if it works like its critics fear, as can all the other suspects one might have. To the extent one disagrees with this, the word ‘objective’ is being used to dismiss concerns other than access to material goods as not ‘objective.’

If you want to use that definition, fine, you can use that word in that way. In which case I do not much care whether the ‘worse’ is ‘objective.’

(Also, you can’t both assert factors like ‘tolerance for many groups is way up’ as objectively good and then reject factors like ‘tolerance for not using social media is way down’ as not objectively bad. Both are real, and they are equally ‘objective.’)

That does not tell us what is causing the kids to not be okay. It does make it less likely that we should be looking mostly or exclusively at social media, or at wokeness, or fear of climate change, since none of those can explain the early 1990s. That would require the two peaks have distinct causes.

Children Versus Adults

Should the cause differentiate adults from children? Adults continue to say they are happy with their own lives despite not being happy with things in general (source). To the extent that their happiness with things in general changed, it does not correspond at all to when the kids were relatively not okay.

All the usual suspects correlate, in case anyone is pretending they don’t.

An alternative hypothesis is that perhaps adults are happy with their lives largely relative to the baseline of what they see as the lives of others around them, rather than as an absolute thing. Being more worried about losing one’s job makes you not okay, but it could also make you more satisfied with the job you do (at least for now) have. You can see 2008 on the personal satisfaction line, but it is a rather small effect. Whereas kids perhaps have not learned these tricks so much yet, and only observe that things are not okay.

School Daze

A reasonable suspect for the core problem would be American schools. Remember that suicide rates go up during school, go down during summer vacation. When there were school closings, suicide rates declined.

Robin Hanson thinks this is clear, responding to the new paper reported via MR to have shown a negative log-linear relationship between per-capita GDP and adolescent life satisfaction.

If a group is attempting suicide this frequently, reports of life satisfaction this high do not make sense unless they represent comparison to expectations, or to the lives of others. We need to look for a better understanding of what such responses mean.

The problem with the school hypothesis is that while it explains kids not being okay in general, it does not explain the changes over time. If you buy as I do the hypothesis that our schools have been making kids miserable, why would that effect have gone down and then gone back up again?

I can tell a story for why school was especially toxic during the pandemic. ‘Remote learning’ was a new level of dystopian nightmare. That still does not fit the graphs.

I can tell a story where recently schools have become more controlling and restrictive, perhaps more woke and liable to alarm kids regarding climate change or gun violence, they interact in toxic ways with social media. Heck, they’re doing mandatory trauma infliction periodically, which they call active shooter drills.

That all seems like it doesn’t sufficiently differentiate school from these other candidate source factors, and we would still need a second story for how those things had local peaks in the 1990s, which doesn’t seem right.

Thus I would say that school lays the foundation for children to be miserable. I would say school directly causes children to be miserable. It still does not seem to explain why things recently got so much worse.

Liberal Politics

Matt Yglesias suggests we look at politics, and why young liberals are so much more depressed than young conservatives. He points to a study looking at depression in adolescents by political beliefs.

I notice that this graph is suggesting something happened around 2011 that impacted everyone, and disproportionally impacted only liberal girls. Until then, liberal girls and liberal boys had similar depressive levels. Even now, conservative boys and conservative girls are similar, and the temporary difference ran the other way. The conservative vs. liberal gap among boys is similar in 2005 and 2018.

The story this data is telling is something like:

Liberal children are more often depressed than conservative children.

Since 2005, depression among children has risen across the board.

Since 2005, something has made liberal girls in particular more depressed.

Causation between politics and depression is not obvious here. All of these stories seem plausible:

If you are depressed, that tends to make you liberal. Change is needed.

If you are liberal, that tends to make you depressed. Change is needed.

If you are liberal, you tend to identify as depressed more often.

If you are attending liberal-area school, you’ll report depression more often.

If you are around liberals more in person, you’ll report depression more often.

Liberal parents are raising their kids in ways that cause more depression, and kids tend to adopt the ideologies of their parents.

Urban areas lead to greater risk of childhood depression, and are liberal.

A left-wing theory by authors of a paper on the subject of why this is happening is that it is all because bad political actors are doing bad things, which are very depressing if you are a good person who understands. I’ll quote the same passage as Yglesias does, except for spacing:

Adolescents in the 2010s endured a series of significant political events that may have influenced their mental health.

The first Black president, Democrat Barack Obama, was elected to office in 2008, during which time the Great Recession crippled the US economy (Mukunda 2018), widened income inequality (Kochhar & Fry 2014) and exacerbated the student debt crisis (Stiglitz 2013).

The following year, Republicans took control of the Congress and then, in 2014, of the Senate. Just two years later, Republican Donald Trump was elected to office, appointing a conservative supreme court and deeply polarizing the nation through erratic leadership (Abeshouse 2019).

Throughout this period, war, climate change (O’Brien, Selboe, & Hawyard 2019), school shootings (Witt 2019), structural racism (Worland 2020), police violence against Black people (Obasogie 2020), pervasive sexism and sexual assault (Morrison-Beedy & Grove 2019), and rampant socioeconomic inequality (Kochhar & Cilluffo 2019) became unavoidable features of political discourse.

In response, youth movements promoting direct action and political change emerged in the face of inaction by policymakers to address critical issues (Fisher & Nasrin 2021, Haenschen & Tedesco 2020). Liberal adolescents may have therefore experienced alienation within a growing conservative political climate such that their mental health suffered in comparison to that of their conservative peers whose hegemonic views were flourishing.

To me and to Matthew Yglesias, this sounds like a story of political discourse among and directed to young people making them depressed.

This is not plausibly a story about a society that was suddenly overcome by a huge rise in war (which wars is this even claiming to be talking about given the time frame, I seriously have no idea?) or any of the other non-economic factors. For economics, the timing does not match, nor is there any reason bad economic prospects should depress liberals but not conservatives during a period where both parties took turns in political office.

This is instead a story about how these bad things became central and constant parts of the discourse that young people felt socially obligated to discuss and endorse. As the authors say, they became ‘unavoidable.’

Young people in liberal peer group social circles – which is most young people, especially given the internet – were increasingly socially punished for not expressing the view that a lot of extremely depressing things were happening. Social media amplified this quite a lot. The youth both had to endorse that these things were depressing and terrible and unacceptable, focusing carefully on the current thing of the week, and signal that this depressed them, and also express the belief that these things were getting worse.

That certainly sounds like it would cause a lot of depression, regardless of the truth the claims subject to these social cascades.

Regardless of the extent to which these issues are central, I highly endorse not catastrophizing, and not encouraging others to catastrophize.

These last few weeks, I have written two giant posts covering events that Isee as plausibly leading directly to all humans being killed and the wiping out of all value in the universe. I have seen the richest man in the world announce his intention to do the worst possible thing he could do, to make the problem arrive faster and be that much harder to solve. Whether or not you (or most others) agree with this perspective on recent events in AI, it is my perspective, yet I do my best to (mostly successfully) keep smiling.

It is important to cultivate the skill of not letting such things bring you down, and to encourage a discourse and culture that helps others not be brought down rather than reinforcing such failure modes.

Whereas, as far as I can tell, liberal discourse explicitly reinforces not doing that.

Another aspect of liberal politics is the focus on various forms of identity, including demands for how kids must react to things and then potentially severe punishment if caught reacting the ‘wrong’ way, except for the hot and popular kids who of course react the way they always have and get away with it.

All of this is also plausibly very not good for kids’ mental health, and plausibly much more not good than the (also not good) traditional versions.

Then there is the tendency to medicate children every time they get out of line or pose any sort of problem, or are given any kind of label that needs fixing – you can imagine why worries about this happening could make one paranoid and unhappy. Also the drugs themselves often make kids unhappy.

I had a rough childhood in many ways. I never got any sort of formal diagnosis, and was never put on medication. Whatever other things I might be mad about, I am deeply grateful for both of these things.

These days? Not a chance. There is more to say here, but I would leave it as an exercise to the reader.

Phones and Social Media

The Social Media Hypothesis (SMH) is both common and common sense. It is easy to see why we might expect social media to be (1) damaging to everyone, (2) especially damaging to teenagers, (3) even more damaging to girls and (4) extremely difficult to escape even when you know about the problem.

The timing also matches quite well, although it obviously can’t explain the 90s.

Richard Hanania considers the SMH. He notes that given his other views he has strong motivations to reject the SMH and instead blame anything else and especially to blame wokeness. Despite this, he is convinced:

After looking at various kinds of evidence, however, I have changed my mind. This essay sets out to explain why I think that the rise of social media has had disastrous effects on the mental health of young people. First, randomized control trials show that quitting or cutting back on Facebook is good for your mental health. It’s true that some studies show a null or even opposite effect, but, as I explain, the studies supporting the hypothesis that social media causes misery tend to be larger and more convincing. Second, I looked to see whether the increase in teen depression since around 2010 can be found in other developed countries. The answer is mostly yes, and some of this data is extremely impressive in that much of it comes from sources that weren’t setting out to prove anything about the social media hypothesis, but found data that supported it anyway. Finding similar trends across the developed world makes it much less likely that something specific to the US like the rise of wokeness can be blamed for teen misery.

He focuses on gold standard RCTs, dismissing quasi-experimental findings and even suicide rates as too confounded.

I am not going to check the primary sources here, so take with that note of caution.

The largest study he cites paid participants to stay off Facebook for a month, which improved their happiness by 0.1 standard deviations (which might not sound like a lot, but under the circumstances is kind of a lot), and caused permanent reductions in Facebook use after the trial period – it looks like a 23% reduction, which lines up exactly with their planned reductions after the trial period, which is weird because one would expect big willpower issues.

I would also note that abandoning Facebook suddenly carries costs due to network effects, so everyone getting off it at once would presumably have a larger positive effect, everyone never joining in the first place an even larger one, and then there’s the question of substitution by other social media.

The second largest study finds an even bigger effect, again from Facebook explicitly. Whereas the largest study Hanania found with negative findings was over the course of two days and doesn’t seem like it was measuring much that is useful.

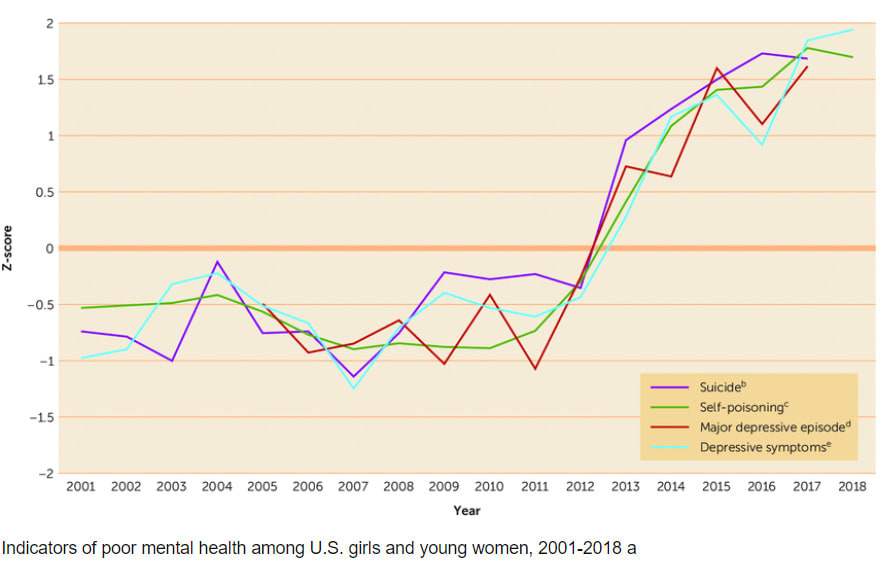

Hanania then surveys studies on rates of depression around the developed world, finds that the trends are not isolated to America. This matches what phones would do, and rules out many (but far from all) other hypotheses as central explanations.

He then notices that Covid caused a lot of additional mental distress, which I don’t doubt but comes too late to explain most of what we are observing.

Noah Smith later points to the study Lambert et al from 2022, where a week off of all the major social media cites improved well-being and depression, which certainly is evidence but to know anything terribly useful we need longer observation periods. There are a lot of studies that point in this direction, but there are a lot of studies period, and most don’t measure what we need to know.

Johnathan Haidt notes that his larger story is the transition from play based childhood to phone based childhood.

In brief, it’s the transition from a play-based childhood involving a lot of risky unsupervised play, which is essential for overcoming fear and fragility, to a phone-based childhood which blocks normal human development by taking time away from sleep, play, and in-person socializing, as well as causing addiction and drowning kids in social comparisons they can’t win.

He also frames the social media, I think correctly, as primarily about network effects rather than individuals or dose-response effects. The existence of social media transforms the social landscape. As an adult, one can mitigate this by choosing one’s friends and colleagues. As a young student in school, you have no chance.

Correlation is not causation, it is easy to see causation running partly the other way, the correlation is still pretty strong here.

He also claims that studies often support that social media use at Time T predicts poor mental health at time T+1. I’d need to check a few details before I’d agree.

Derek Thompson did a podcast about this, and both he and his guest endorsed the social media hypothesis.

The theory here was that this hits girls much harder than boys because girls are far more vulnerable to social comparison, which social media forces on them even more and worse than traditional media.

They also focus on the contrast of passive scrolling versus active use. Actively talking to people you know, arranging events and other similar things, in this view, are fine. That, too, makes sense to me. The problem is modern social media pushes against this. Even when you are being active, there is a huge push to do what will go viral or be popular.

Accounts of all sizes, in my experience, do both kinds of behavior. My experience is that as I get more followers I become more conscious of wanting not to waste people’s time or drive them away, whereas if my followers were mainly people I know I think I’d post more freely. My self-awareness might be lacking, though.

What I am confident is making this worse is the transition away from seeing your followers or friends stuff and towards algorithmic feeds. When I post something on Twitter that the algorithm does not care for, maybe 10% of my followers will see it. When I post something that catches fire, sky is the limit. Most of my views on Twitter come from a handful of posts – which means your likes and retweets actually matter a lot for effective visibility, and are appreciated.

Noah Smith agrees: It’s probably the phones. Here’s his fresh variation of everyone’s favorite graphs.

Why would that make us unhappy? There’s an obvious reason: social isolation.

…

As the natural experiment of the pandemic demonstrated, physical interaction is important. Text is a highly attenuated medium — it’s slow and cumbersome, and an ocean of nuance and tone and emotion is lost. Even video chat is a highly incomplete substitute for physical interaction.

This graph looks quite a lot like the depression graphs, note this ends in 2016. Once again, something quite terrible happened around 2011 or 2012.

And look, it’s the reverse version.

My experiences growing up strongly confirm this. When I got to spend a bunch of time with friends, that was a much better day than whenever I didn’t.

It is noteworthy that the 1990s did not have especially low numbers here, things slowly got worse until finally the bottom fell out.

Here’s another happiness graph for comparison.

Noah doesn’t consider it that meaningful to differentiate the phones versus social media, since to have anything like its full effects social media requires phones. It does still point to very different best responses now.

Arnold Kling also surveys the situation, concludes it is ’all one big unhappy loop of reinforcement, connecting a neurotic temperament, smart phone technology, social media and pathological progressive politics.

A consequence of social media and phones that needs more attention is the destruction of privacy and the expansion of the permanent record.

When socialization takes place in a medium that is largely public record, it destroys privacy. It means one must constantly be on guard for what anyone, now or in the future might have to say or think about what you are up to. Even if you are communicating in a private channel, it is recorded, so there is every reason to worry that it might eventually be made public or used against you.

This then combines with a zero-tolerance policy for many things, often things that were widely considered fine not too long ago, and that can ruin your entire life plan. Every attempt to talk to another person, especially to perhaps date them, is an existential risk. Colleges rescind admissions based on a single social media post taken out of context. Schools suspend you. You have no room to experiment, to breathe, to make mistakes.

I think this is a pretty big deal.

How do we solve this? I would start by normalizing vanishing messages and auto-deletion of posts, and making it out of bounds to do unannounced recording, as a start.

Is This Core Case for the Social Media Hypothesis Convincing? Is It The Phones?

Mostly, yes.

I am convinced that the central problem here is likely a combination of phones, social media and the resulting physical social isolation. Kids aren’t seeing friends in person, they often don’t even have good friends, they’re instead scrolling on their phones, and this is bad for them.

Phones also expose children (and adults) to a bunch of other information in ways that seem plausibly to do great harm to their lived experiences and mental health, as I discuss in the two sections after this one.

There are a lot of different angles of evidence gathered to support the phone hypothesis. Except for the need to explain the 1990s, and discounting the misleading alarmist stuff, they all point in the same direction – the phones.

The population data over time is to me the strongest evidence.

There is little question that something very terrible for teenagers happened around 2012. That rules out an economic cause. That rules out some weird political shift, other than the shift in discourse that came from the rise of phones and social media. The only two things suggested that could possibly match the timing at all are a cultural shift (e.g. towards some form of social-media-and-being-online-reinforced wokeness.)

Wokeness would plausibly hit the mental health of girls and liberals harder, and the timeline isn’t completely crazy. It still is a far less good match, the timing isn’t quite right here, takeoff would be more gradual at first and if the action mechanism is ‘world seems terrible to students’ then you’d expect a large spike when Trump was elected, and it isn’t there. Whereas for phones timing is almost too perfect, and have the studies behind them.

I do see a role here for political viewpoints, but mostly or entirely as acting through phones and social media. The phones and social media make everyone Too Online, they create pressure to keep up with and affirm current thing, create signaling cascades and so on. Such toxic dynamics are part of the story of phones and social media, without those (in this model) these dynamics wouldn’t be that big a deal. Or: Yes what you are talking about on tumblr might be making you miserable, but that has less to do with the particular details of what you’re discussing and more to do with tumblr.

What About Other Causes?

That is not to say that there aren’t plenty of other things that are not great and one would do well to fix, both things that are getting worse and things that have always sucked.

Our screen problem is not limited to phones, there are also tablets and computers and good old fashioned televisions. Plausibly the damage compounds over time and generations.

Tablets are a serious problem for younger children. I know of a number of examples of children who are very very attached to their tablets. If you are not careful, they will lose interest in everything else in favor of a bunch of optimized dreck. This kind of thing can easily compound if allowed to fester. The timeline would be a few years delayed so it doesn’t match, but it’s a real issue. Of course, good tablet applications are insanely great here, if you put in the work and keep it in moderation.

Computers and video games are the screens that came online in the 1990s. Could that have been what happened then? In the early-mid 1980s, you played video games in an arcade. The arcade was social, and it cost money per play so it was limiting. Then kids started getting their hands on an NES or a PC. And at first NES was super awesome and kids played together and had the same three games but then things branched out and the SNES/Genesis era was more insular and also more all-consuming, and things went south for a bit until we learned how to handle it?

One could tell a story of computers and video games being social in the 80s, then isolating in the 90s, then early internet bringing us together in the 00s, only to have phones and social media turn it all toxic in the 10s. It’s a theory. It’s the only one I could come up with that even pretends to explain the 90s. Paging Chuck Klosterman.

A common pattern when dismissing the dangers of new tech is to say ‘remember how everyone said television would rot our brains and destroy our communities? You know, like Socrates worried about books?’ Books turned out to be good, but television? Have we considered that perhaps, while there is also plenty of good television out there that enhances our lives and culture, those warnings were one hundred percent right? And then it pretty much happened?

I think it pretty much did happen.

Like phones, television most certainly wasn’t all bad. Used responsibly it’s great.

Still happened.

The whole ‘too much screen time’ concern is very real. One difference is that with television you had a much easier time imposing limits than you do now with phones. The television stayed in one place, and wasn’t a means of socialization.

The social isolation problem, and lack of community, predates smart phones and even widespread video games and computers. Remember Bowling Alone? I do think that phenomenon was real and important then, and has been massively amplified now. Its other causes count too.

What role do economic issues have, the fear of not being able to get job or support a family or the terror of endless school and student loan debt, or the competition to get into a good college or else not be employable?

I do know the timing does not match. It is not obvious to me the extent to which these things got worse over this period, but I am confident they did not suddenly get worse in 2011-2013, whereas they did get worse in 2007-2008. The ’90s don’t seem like they were a time of unusually high economic worry either.

This could still be an important contributing factor, I do think we are not doing a good job measuring the lived expectations of youth when we point to our economic statistics.

Perhaps young people now better know their situations, aren’t fooled by our slogans and statistics, and are not so happy about it?

Perhaps The Truth Can Be Rather Depressing?

I have several times seen claims that depressed people see the world more accurately in its details, whereas most people are overly optimistic and rosy on those details.

What about if all this wasn’t about actual economic problems, or other problems, but the newfound perception of those problems? That could alter the timing and brings us back to the smart phones.

Under this theory, economic, career and lifestyle expectations for many have been declining for decades. Our system fell into great stagnation, rent seekers have been stealing opportunity by locking up housing markets and jacking up health care and education costs and such. Our culture has stopped respecting core human needs like raising a family. As the competition tightens, and you need a college degree to get any decent job, childhood becomes a tightrope of cutthroat competition rather than a time for exploration and joy. We are failing our young people.

For a while, this theory might say, kids mostly managed not to notice this. When kids go off to college they still mostly choose liberal arts majors and take on debt, f*** around and find out, because they are sold a lie that they won’t get punished for this. Your future sucking doesn’t make you miserable now if you don’t know about it.

Same could be said for plenty of other problems, including all the leftwing favorites: racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, police brutality, the list goes on. By any reasonable standard, humans have been pretty damn horrible about all that for at least as long as we’ve wanted to have cities enough to build roads.

Similarly, most people throughout history have, by any standard a modern American would consider reasonable, lived really terrible economic lives. They struggled to keep a roof over their head, food on the table and everyone clothed. People did not automatically get to save up to have secure and comfortable retirements. We did not follow our passions and love our jobs, we worked where we could find work. Kids were forced to work terrible jobs. We did not have ready access to health care, fair treatment or effective due process of law, and if you wanted to live any kind of alternative lifestyle then good luck with that.

Many, many things we consider standard now were luxuries.

Then came smart phones and being constantly online. The truth came out.

We could no longer maintain our mismatches between our rhetoric and reality. Kids could no longer be gently introduced to the realities of the world over time. And switching fully over to what our rhetoric implies is not actually possible, because continued physical existence does not care what your principles are, and our view of what our principles should be will always be ahead of whatever we can pull off.

It was all really freaking upsetting and depressing, perhaps?

Under this theory, smart phones did not make us miserable because we are using them to engage in ‘unhealthy behaviors and comparisons.’ They are making us miserable because they woke us up to our problems – one could say they made us ‘woke.’ How much of that is economic reality versus social reality or other problems one can debate.

We all hide some truths from our kids. Disagreements are a matter of details, and a matter of degree – we don’t want to overwhelm our children with thoughts of man’s inhumanity to man, of suffering and hunger and nuclear firestorms and misery and death. We also quite reasonably hold back various stuff about sex – except now everyone with internet access has unlimited free hardcore porn. There is a term ‘grow up too soon’ for a reason.

I strongly don’t believe in lying to kids, that still doesn’t mean dumping the weight of the world on them all at once at age seven, or even twelve, or ideally even seventeen2.

At this point, we kind of do exactly that. It is all right there, right in your face, and it is on you as a student to be ‘raising awareness’ of it all. Maybe that really, really sucks?

Combine that with what has been called the Revolution of Rising Expectations, where we continuously raise our standards on all fronts, doing social comparisons with all the unrealistic reference classes from individuals up through to civilizations, with a laser focus on the exact places either you or the collective we are visibly falling short. What did you think was going to happen?

This theory doesn’t centrally say ‘blame liberal politics’ as much as us being a little itchy on the trigger with pointing out that Life’s a Bitch and Then You Die in all its forms. There are plenty of ugly truths out there. No one has a monopoly, and everyone has a web browser. The political response could scarcely be otherwise. Perhaps it is mostly result rather than cause.

Looping back to the economic and competition aspects, kids nowadays can very clearly see how rough it is going to be out there for them.

That, in turn, makes their real physical situation worse.

If kids are mostly going around being kids and then colleges judge them, and then employers judge them on where they went to college and what they studied, and there are lots of consequences for messing up at every step, and the losers suffer a lot? The few who are highly motivated to get ahead mostly can get ahead. The suffering of the losers is not great, but the kids get to be kids, life gets to be lived, we play and learn and love and so on.

If that is all happening and it is common knowledge, that is so much worse. If you don’t start optimizing for the metrics in order to have a childhood, you’re increasingly screwed. Everyone is suddenly spending their adolescence in a rigid thankless contest to present themselves the right way, building the best possible resume, learning all the right passwords and that actually living life is not a luxury they can afford or so important to their lives. Then the distribution of final economic outcomes doesn’t change and everyone has had less fun, is less of an actual person and is in worse mental health. Moloch triumphs. This seems really, really bad.

If all of this is happening, it is common knowledge, except that people think things are even worse than they are, that’s even worse than an accurate perception. Parents and kids are convinced you absolutely have to stay on the straight and narrow and go to the best possible schools and all that, or you’re finished. And, frankly, that’s not true. You can and likely should go out there, start a business, join a start-up, find ways to do real things and get paid for it regardless of your educational resume. And you can always learn to code (or, for now, among other things, play poker, and also none of this is investment advice or career advice and so on, standard invocation). Things are not so great out there, but people think they’re even worse, which is making them continuously get worse.

A similar pattern on the personal level is what happens if we now more reliably learn about, understand and process information about bad things that have happened to us, difficulties and disadvantages we have, and ways in which we diverge from the normal, that isn’t going to always make us happier or better off, adjustments made in response are often harmful. One way that happens is that we calibrate our understanding of a problem based on the group that couldn’t hide the problem, and then tell the mild cases that could have muddled through that they have this terrible problem, and how bad it must be. It often goes poorly. The correct level of walking things off is not zero.

There is also a big fertility effect from all this, as kids despair of having the resources to raise families so they don’t plan on it, they increasingly don’t even party or have sex. Even when they do get into position later on, they don’t relish their children having to go through the same obstacle course, and they feel obligated to provide everything to let their children succeed at that, which raises their felt financial and other burdens a lot.

The same dynamics, in various ways, also are contributing to increasingly harsh restrictions on children’s ability to exist and be kids, which in turn is crippling their social lives and making them miserable well beyond what makes sense from the game theory involved.

Compare this to the ‘revolt of the public’ theory. What if this revolt is that much more widespread, for most of the same reasons?

Perhaps We’re Spouting All Sorts of Obvious Nonsense?

When the things people say don’t make sense, and you are not yet old enough to have been beaten down enough to stop noticing, it could be kind of depressing.

I am not going to formally defend such claims or cite examples or cite causes beyond phones and social media definitely being a contributing factor, and I won’t be taking any questions.

I will simply say, for completeness, that it is my belief that the overall quality of discourse has radically declined during the period in question, the number of people capable of good discourse has radically declined, the sanity waterline has receded, and it is commonly demanded that people endorse or at least not oppose various things that are obvious nonsense on a continuous basis.

I’m also just going to leave this here, don’t mind me.

What Is To Be Done about Ubiquitous Phone Use and Social Media?

So what do we do about all this?

Whatever other problems are here, social media is making things far worse. What can we do about it?

What won’t work is advising kids of the harm social media does. Even if they can overcome the addictive properties and make an intentional choice, they are stuck in an inadequate equilibrium. The inadequate equilibrium with social media problem is obvious. Even for an individual, turning off one’s phone or deleting one’s accounts is hard. Once all your peer group’s social coordination is on social media, what are you going to do about it?

Being a full-on weirdo no one knows how to contact is not exactly the way to go back to hanging out with friends all the time and having a rich social life.

Even if true, I do not see how this is an answer. Magnitude matters. So does the direction of the effect.

As an obvious parallel, at times in the past, smoking was a key part of socialization. If you wanted to hang out with the cool people, you had to smoke. So lots of people smoked, which meant lots of other people smoked, and everyone was colder and sicker and poorer and worse off. It is at least reasonable to propose a regulation to shift the norm away from that, where restricting people’s choices makes everyone better off. If it’s kids, the case is that much stronger.

If your friends use of social media is bad for teenagers, as it seems to be, that is an externality. Externalities are a classic market failure that, if big enough and important enough, justify intervention to fix them, ideally in the form of a tax but alternatives can easily be superior to nothing.

Would I support stricter age restrictions on social media or smartphone use?

I am loathe to have the government come in and start restricting our ability to communicate. The problem is that the statistics here are really, really dreadful and horrifying. So I’m on the fence about that. In practice, I’m probably still against it – I’d be for the ideal version but we won’t get the ideal version, and also I don’t want to get into bad habits.

If we can’t reduce usage, one idea as hinted at above is perhaps to make evidence drawn from children’s social media and electronic communications broadly inadmissible. Make it hide auto-delete or at least hide from everyone else by default after a while, viewable only by friends, illegal to consider in any school disciplinary action or admissions process or job interview.

I do know that I want my own children to stay off social media, and minimize their ownership and use of smart phones, for as long as they possibly can. And that I intend to spend quite a lot of my available points, if needed, to fight for this. And that if I was running a school I’d do my best to shut the phones down during school hours.

The only solution to phone use in general is a cultural shift. Being on your phone actually pretty much sucks. I am very rarely on my phone, and constantly strive to be on it less. I don’t play games on my phone. Constantly checking your phone also sucks.

If this was merely a collective action or externality problem I would despair, but you really are better using the larger screens sometimes and mostly unplugging (aside from things like logistical coordination and directions, and actual phone calls) otherwise. So if nothing else was about to hugely disrupt such dynamics I’d expect a cultural shift to start improving things.

Well, whoops. Social media and phone use are about to crash head first into the problem of ubiquitous and rapidly advancing AI. If it wasn’t for AI, I’d say I expect the social media issues are now about as bad as they are going to get and should improve as we adapt to the new world, and that the culture should start shifting soon to get people to look up from their phones more often. Instead, things are about to get super weird, in ways that are very hard to predict.

We can also help this along by improving alternatives to phone use. If children aren’t allowed to go places without adults knowing, or worse adults driving them and coming along and watching them, what do you think they are going to do all day? What choices do they have?

The more we allow and encourage free range childhood at all, in our actually vastly safer world, and encourage rather than discourage the kinds of in-person social interactions kids are missing, the more they won’t need to be on phones all day.

Another potential idea is a rule against any major product (in terms of number of users) that has features that are available on a phone app and not on a desktop. Forcing people to use their phones like this is feeding toxic habits.

What is To Be Done About Information Overload?

The exposure to information problem is that much tougher. If your fellow students know things, you get to know them too. Cultural shifts don’t have opt outs either. There is no way for families to opt out of any of it without radically altering their lifestyles, and even that likely doesn’t work. Any government intervention with much chance of working here would be far worse than the disease.

So the unfortunate answer is, essentially, ‘not much.’ We can avoid making it actively worse, but I don’t see what else we can do on a societal level.

What About Other Economic and Social Problems?

The economic and social problems, and other lived experience issues, can be divided into perception versus expectations versus reality.

For fixing the reality, how to Do Better, and in what ways we must Do Better, is of course an endless debate – I won’t get into it here beyond strongly asserting there is lots of low hanging fruit.

For fixing perception, there are the places where the problem is that perception is wrong and the places where perception is right but causing problems.

Where it is wrong and doing harm, the ideal answer is obvious, but also sometimes one must actually ‘fix’ the problem due to such perceptions alone. If no one will fly in an airplane unless they are a hundred times as safe as it otherwise makes sense to make them, well, I have news about how safe you are going to make your planes.

Where it is right but doing harm, that is tricker. Going back to lying is not going to work. You never want to be in this spot, in any context:

We can take individual-level steps to shield info for a time, but that is also severely limited.

The obvious solution is ‘fix the underlying problem and ensure people realize this,’ which when feasible is obviously insanely great.

Alas, depending on political and social realities, and on the physical aspects of the problem, that may not be possible.

That brings us to the problem of rising expectations.

In many cases, our expectations for economic or social progress have become completely divorced from physical reality and how humans and civilization work. In others, expectations automatically ratchet to the level above wherever one happens to be, so they can never be satisfied.

So we might correctly understand what is happening, and still find it is impossible to ‘fix’ what is happening. This could be either because the problem is inherent to civilization and humans and the fix flat out can’t be done, or maybe it could in theory be solved but the fix would break other things and make things worse or be absurdly expensive, or the fix would cause a shift in expectations and thus would not solve the central problem.

Then what?

Lowered expectations? Hopefully via better understanding of the problems, but also perhaps when that isn’t working some ordinary despair and willingness to compromise, realizing that things are actually pretty good, considering?

I mean, kind of, yeah. Otherwise, I don’t know. I don’t think anyone else knows either.

Ideally with a large side of actually doing much better, and acting as if the kids are not okay and constantly on their phones for good reasons – that we’ve robbed them of their alternatives and their futures and their freedom and their privacy, so perhaps we should give some of those things back.

Other problems resulting from cultural shifts will be similarly hard to reverse, the damage has been done. It is still possible, all such things go in cycles rather than only getting worse.

Conclusion and First Step

I wish I knew of better answers.

The good news is that for most of us, ubiquitous use of smart phones and social media is transparently terrible for us. This isn’t an inadequate equilibrium if it is not an equilibrium. There is a reason so many comedians and other famous people talk about locking their phones so they can’t use them for anything but a few basic functions.

You can profitably be the change you want to see in the world here. My recommendation for adults (including myself, some of this is aspirational)is that you do the following, and insist kids do the same:

Don’t ever passively use social media on your phone. No scrolling, ever.

Cut down social media use as much as you can even on your computer. Twitter is a strange hybrid case where I think it is often necessary, but f*** Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram and TikTok unless you’re actively doing business or logistics.

Don’t ever play games on your phone.

Don’t do anything on your phone that you could do better on your computer.

Also, get yourself a desktop computer with a large monitor. Walk over, use that.

When you are at home, don’t even have your phone next to you if you’re not expecting or in a call or actively texting. When you’re not at home, unless you have a specific thing to be doing, don’t take it out. Never scroll. Be present. In case of boredom, see the approved uses list.

Don’t never take pictures but mostly never take pictures.

Turn off all non-essential notifications in all forms, definitely including email.

Actively fine uses of a smartphone include: Maps and directions, phone calls and video calls, reading e-books, playing music and podcasts and audio books, quickly looking up relevant information, storing tickets or otherwise showing others info.

Look upon all other uses as highly suspicious.

…and make concerted efforts to see people in person as often as possible. I have been failing at this one since the birth of my third child. I need to do better.

So do we all.

ChatGPT’s top 5 candidates in order, after failing to come up with a good song completion (not that I tried that hard): Financial Pressure, Lack of Good Role Models, Social Media and Cell Phones, Fear of Failure, Need for Friends and Lack of Self-Care.

Or 44, really, my first hand report is that it still isn’t any fun.

Something I rarely see considered in hypotheses of childhood happiness and rather wish there was more discussion of, is the ubiquity of parental and state control over children’s lives. The more systems that are created to try and protect and nurture children, the more those same systems end up controlling and disempowering them. Feelings of confinement, entrapment, and hopeless disempowerment are the main pathways to suicidal ideation and our entire industrial childrearing complex is basically a forced exercise in ritualistic disempowerment. Children are legally the property of their parents and the system is set up to constantly remind them that they are property, not people, and that they can’t stand up for themselves without being infinitely out-escalated by their parents with the full backing of their governments. Technology has only made this worse, and resulted in more and more layers of control being draped over kids in a misguided attempt to steer them away from danger and leaves them feeling trapped and hopeless.

These may be true, but it is unclear how they are relevant to explaining the recent trends and how they differ by groups. There is, and long has been, intense state & parental control of childrens’ lives and often not for the better: but how does that explain a change in trends in 2011 to increase, prior decreases in the 1990s, experimental results like quitting social media (where parental/state oversight is minimal) apparently increasing mental health, or differences like ‘liberal girls are more affected than conservative girls’?

Control is not a constant, and ability to effectively control depends on the social context. The state itself has acted as a counterweight to parental control for hundreds of years, and capital also acts as a counterweight—if you don’t want to live the way your parents want you to live or marry who they want you to marry, you can run away to the city and live free, which is easier if there are strong laws preventing you from being hunted down and honor-killed and jobs waiting for you in the urban center. Control was arguably at all-time lows in the late 60s and 70s. But the 80s are a period of reaction against these excesses, and safetyism can be argued to have started in the 80s. The first law mandating car seats is passed in 1979 and the first law mandating seat belts in 1984. More tellingly, the satanic ritual abuse panic kicks off hard in 1983 with the McMartin trial and the next year satanic ritual abuse panic advocates testify before Congress. Stranger danger spreads as a meme, reducing the ability of young people to travel freely via hitchhiking, even though the actual risk remains low.

The Internet disrupts this control process by creating a new space where young people are more able to navigate than parents. I’d argue this is the cause of the decline through the 90s: increased freedom from the nascent Internet. Gradually, this is curtailed as BBSs become forums, and forums become social media. At the same time, censorship is productized and sold to parents, and as early as 2008 schools were having extracurricular brainwashing sessions designed to scare children away from using the Internet as a vehicle of expression because “what’s on the Internet is forever.” I do not understand how parental and state oversight could be said to be minimal on social media. Schools install spyware on their own devices and recommend parents do the same. “Parental control features” are ubiquitous and you can’t crack your mom’s password with a l0phtcrack CD because Windows Vista didn’t use NTLM hashes. The endpoints are controlled. You live in a panopticon. Even Kindles have parental controls, but paper books don’t.

2011 is arguably the death rattle of free speech on the Internet. Wikileaks goes from being the place where you download the Scientology PDFs to being a terrorist group in the eyes of the US government and I think promotes a lot more walling-off of the gardens of the Internet. Reddit shuts down several subreddits in 2011, going from being a free speech social media website to what it is now. SOPA is introduced in October. If the Internet gave young people hope in the 90s, 2011 is the year that hope started dying, amidst the Arab Spring, the Eurozone collapse, and the Occupy movement. The high school first years in the fall of 2011 would graduate the spring of 2016, just in time to see Trump elected.

And finally, conservatives live in the country. The country is inherently less conducive to control than the city. Insurgents hide in the countryside. People go to parties in the fields. You can light huge bonfires and get drunk next to them and nobody will see or hear you. People in cities have to have better coordinating to create spaces like this, which is limited by a censored and surveilled Internet. Conservativism as an ideology is less conducive to paternalistic control. But I think the urban/rural divide is the main driver here.

We have been going through a societal cycle of increasing control since the 80s that was disrupted by the computer and the Internet, but since 2011, smartphones, and social media, the Internet has become another vehicle of control, rather than the liberatory technology it once was that made life literally worth living for so many young people. To me, this explains all of the holes much more parsimoniously than “Socrates was wrong about books, but I’m right about

network televisionOne additional factor that would lead to increasing rates of depression is the rise in sleep deprivation. Sleep deprivation leads to poor mental health and is also a result of increased device usage.

From https://www.ksjbam.com/2022/02/23/states-where-teens-dont-get-enough-sleep/:

https://www.prb.org/resources/more-sleep-could-improve-many-u-s-teenagers-mental-health/:

As for school daze: I can easily tell a story for how academic stress has risen over the past decade. As college admissions become more selective, top high school students are trying to juggle increasing levels of schoolwork and extracurriculars in order to try to get into a top university. See also NYU Study Examines Top High School Students’ Stress and Coping Mechanisms.

Anecdote: I have ADHD, which went undiagnosed in high school and most of college. Digital media, my poor impulse control, and school/work waking-times all combined to drastically make my overall well-being worse. My ideal day would start at noon, and it rarely happens. My sleep cycle might run on >24 hours, I don’t know at this point but it seems plausible that I’d “drift forward” if left to my own devices.

Thank you Zvi for writing this excellent post that has helped my research immensely. I will make sure that this post’s research will be used to help other people’s research immensely as well, even if it doesn’t here.

I’ve researched this class of problem professionally, full time, for more than 3 years now. I’ve already found the best hack that mostly solves the problem is to rejigger chrome’s autofill to go exactly to the valuable pages and away from any news feed/scrolling. This is how you do it:

When you go to facebook on a desktop, you type “F” into the chrome bar and it autofills to “facebook.com″ which takes you directly to the news feed for scrolling. What you want instead is to type “F” and it autofills to ”https://www.facebook.com/duncan.sabien″ instead.

Write down/print a list of all the social media accounts that are worth looking at. In my case, that includes Eliezer Yudkowsky’s twitter and Duncan Sabien’s facebook, which update the most frequently.

For each one, use ctrl + C to copy the url of their home page, and use ctrl + t to create a new tab and ctrl + V to paste it in that new tab, then hit enter. Repeat that around ten times, ctrl + T, ctrl + V, enter

This is the tricky part. Type in the habit-letter into the chrome bar (in this case, “F” for “facebook.com″) then use the arrow keys to select the bad-habit autofill (in this case, ”facebook.com″) and hold down alt + shift + backspace to remove it. Continue using alt +shift +backspace to remove things, until autocorrect only shows you the stuff you want. You might need to reinforce the things you want using the step 3 cycle more than ten times.

The final result should look like this:

In summary:

write down the accounts that are worth looking at (such as Dank EA memes)

copy their url and cycle ctrl + T, ctrl + V, enter, for about 10 iterations

use alt + shift + backspace to delete anything but the accounts that are worth looking at

when you type “f” for facebook, it will show you exactly what you need to see, instead of the main page news feed which is the danger zone

This is the optimal strategy, and I’m only tentatively proposing it because it might lull people into a false sense of security. You are never safe on the contemporary internet. There will always be a springtrap somewhere that disarms you sucks you back into a news feed.

If you’re in the habit of using a phone for leisure, you’re fucked. There are many reasons why, none of which I’m willing to talk about publicly (aside from the news feed issue which is a big one). Zvi underestimates the difficulty of replacing phone usage with desktop/laptop usage, but phone habits will get net-harder to quit with every year that passes (possibly a little easier, probably much harder) so you might as well do it now.

If you want to make people good at skilling up for alignment technical work (e.g. if their brain-type is unique enough for them to have good odds of ending up becoming one of the alignment champions), then getting the candidates to switch from phones to desktops is probably one of the biggest bottlenecks.

Anyone up for writing software that can automate this browser process? Seems like it should be viable to write a program that checks all your autocompletes, you tell it what you want to change and then it fixes it via doing the thing a human would do?

Seems like we could use a browser/addon that gives the user more direct control over the autocomplete, rather than writing workarounds to hack bad software.

If this doesn’t work (chrome might refuse to cooperate) you can send an email to yourself containing all the links, and then bookmark the url to that email. After using it for a week or so, you can have that email be second on the list of search suggestions (the correct word for the stuff in the chrome search bar) whenever you type the first letter that takes you to gmail/other mail.

You can also use alt + shift + backspace and ctrl + T, ctrl + V, enter to change that search suggestion to a new updated email with new links. Or, even easier, just make a bookmark to the email to yourself.

Thiseems a bit overkill when there are such things as bookmarks and pinning sites to your home page. Also if you have a bookmark manager app you can just make that your home page.

I’m 3 years late to this party, but i still want to ask: why?

I’m probably one of the lucky few—i tried to use my phone for Facebook and again and again find myself walking to the computer to write comment, because trying to use the phone is unbearable. I find all the descriptions of phone addictivity—not facebook (though it stopped to be addictive with the enshittification, so, i guess i won? I don’t feel like I won) - but phone, incomprehensible.

like… why?

it obvious your model better then mine—I totally fail to understand something i can see all around me. can you explain, please?

I think the strength of your objection here depends on which of two possible underlying models is at play:

The boys who attempt suicide and the girls who attempt suicide are in pretty much the same mental state when they attempt suicide (that is: definitely wanting to end their life). But, for whatever reason, the boys use more effective methods, and so they end up actually dying at a higher rate.

There are two categories of mental states for suicide-attempters: one in which they genuinely and definitely want to die, and will therefore seek out and use effective methods; and one in which they are ok with dying but also would be ok with living and receiving attention, in which case they may use a less effective method

If (1) is the case, then I think it is at least arguable that girls have it worse here, since they end up in the mental state of “definitely wanting to die” more often than boys, and that sucks. That said, it’s still true that they’re not actually dying as much, and so I think it’s still kinda disingenuous to frame it the way the newspaper and experts have here.

If (2) is the case, then that means that boys are ending up in the “definitely wanting to die” state much more often than girls, in which case I’d agree that it’s very wrong to say that girls have it worse.

It also depends if you are going “suicide bad because people dying is bad” or “high suicide rates are evidence for a large number of unhappy people”.

I don’t think this distinction was made in the post.

The quoted possible reason of more attempted firearm use by male adolescents committing suicide can only be a partial explanation.

Looking at the German figures (where firearms are not widely available) from 2021, absolute numbers of suicides:

under 15: m 12, w 15

15-19: m 118, w 44

20-24: m 223, w 83

25-29: m 268, w 58

and from then on about a 3:1 ratio more or less across the age groups.

destatis.de

The elevated male:female suicide ratio is now universal across countries, getting consistently more male-skewed, and some of the countries with the biggest increases, like Iceland and Cuba and Poland, are countries where firearm access is very low. In Poland, 90% of completed suicides are by hanging. So yes, the idea that firearm access is driving this is a parochial US notion.

We have to be careful about all these stats, though. Women tend to choose “softer” suicide methods that may get counted as non-suicides more often than unambiguous male methods of suicide. On the flip side, men may experience depression as anger, not sadness or hopelessness, and may be less open about it overall. So both male depression and female completed suicides may be systematically undercounted across countries. I’m personally more uncertain about the m:f depression ratio than the m:f suicide ratio. I think it is possible that men are both more depressed than women (40% confidence), on the basis of the suicide ratio and evidence of undercounting, and self-harm more severely than women (60% confidence), but mainly I wish we had better data.

The firearm use is a weird thing to point out. The usual explanation I see here is that social programming directed towards women drives them to value appearance more highly and use methods that are not as disfiguring, which means no firearms, but also no trains, bridges, high buildings, and so on.

Social media could be a factor, but a much bigger one is that kids are so ludicrously overcontrolled all day every day that they often get no opportunity for good experiences.

My childhood was much closer to Comazotz from A Wrinkle in Time than to a healthy upbringing.

It’s crazy that even kids today are getting politically aligned now. When I grew up, I had no idea what politics was about. There was no social media, so to get politically aligned, you had to either read the news or watch news on TV. I wonder if it’s parents or their peers are also pressuring kids to get involved in politics.

I don’t think it’s that new or weird, I mean, I guess it depends what you mean by ‘kids’, but universities have been hotbeds of political activism since long before the internet. And I know that I had strong political ‘opinions’ growing up just by virtue of living in a city where 95% of the adults I encountered were liberal. My parents took me and my sister to protests against the Iraq War when I was five despite not being particularly politically involved people, and the 2011 Wisconsin protests happened when I was 14 and I and most of my friends were there (especially since school was canceled, so there wasn’t much reason not to go).

Seems like politics are almost always led by the parties and their leaders themselves rather than the citizens involved. Then the parties themselves take in their supporters reactions and the cycle repeats. There has been an ongoing trend where the two parties in the US are moving further away from each other. This has led to both some people stopped caring as much as they did and some people started caring more than they did before. Those who drop out are more centrist while the more extremes are driven to increased engagement. I wonder if the same trend applies to the topic discussed in this post.

When I was in middle school and high school (Michigan, 1996-2004) the only identifiable political engagement I remember any of my peers doing ever was that we knew it was funny to make fun of George Bush for being an idiot. I don’t remember ever having any other conversation with my friends about any political topic. I certainly had no clue what was going on in politics, outside of knowing who the president was, and knowing that 9/11 happened, and knowing that the Iraq War existed. So the idea that teenagers have political opinions now is also striking to me.

There is a paradox of competence at play regarding the social dynamics of increasing the awareness of any issue.

Experts find something that require awareness in order to induce policy change.

Experts require large social following in order to raise awareness

Social following will not be competent in the topic at hand, will need to just trust that the experts are right

With increased awareness, the oppositions create their own social forces to counter the initial social movement

The public incompetence increases as more people get involved

The original awareness has lost its way and will focus instead on competing the the opposition force

This social dynamic reduces down to “how to attract followers” for any topic, and the topic itself becomes irrelevant.

If anyone can think of a solution to this paradox, I will be forever grateful. I personally can’t. I have spent a couple of years on this already.

I am basically the same age as you, and I remember being very engaged in trying to protest against the Iraq War before it started. But I lived in the suburbs of DC, and so 9/11 was a much bigger deal to me as some of my friends’ parents e.g. worked at the Pentagon, and also just politics and government was a much bigger part of our lives. But perhaps I’m the weird one.

I think this might play a really big role. I’m a teenager and I and all the people I knew during school were very political. At parties people would occasionally talk about politics, in school talking about politics was very common, people occasionally went to demonstrations together, during the EU Parlament election we had a school wide election to see how our school would have voted. Basically I think 95% of students, starting at about age 14, had some sort of Idea about politics most probably had one party they preferred.

We were probably most concerned about climate change, inequality and Trump, Erdogan, Putin all that kind of stuff.

The young people that I know that are depressed are almost all very left wing and basically think capitalism and climate change will kill everyone exept the very rich. But I don’t know if they are depressed because of that (and my sample size is very small).

I think it might be better to think of it this way. The increase in social media usage has changed people’s cognition to a large extend that they are not aware of that exist not only just in politics but everything that has taken root in the collective consciousness. If only 20-30% of any individual’s cognition is focused on the collective topics/consciousness before social media, then I’d say now it’s flipped to 70-80%. We no longer have much free time and free thinking to ourselves these days.

I’ve noticed this change not just in people whom I don’t know but also in people I’ve known since growing up. They used to be different. The popularization of the zeitgeist has drawn those people in. They are tempted to participate, yet they are fully unaware of how participation has gradually changed their own cognitive habits. I was unaware for a long time, but when I decided that I probably need a break from all this stuff, I started looking for trends and started comparing how life was 10-20 years ago.

What you spend time thinking about is subtly robbing you of time and opportunity to think about something else. What that something else is requires your own volition to explore and find out for yourself, instead of being pulled in all directions by the collective.

The power of the human collective has never been stronger. This trend is led by celebrities and figureheads whom themselves are deeply entrenched in the collective consciousness more than most other participants. The sense of power they are experiencing is mesmerizing, thus leading to a form of addiction.

It’s both the technology itself and the convenience of participation. These two trends are reflective of the social model that came before: an increase in the public participation in everything that’s larger than the life of an individual. There are cultural tendencies that shift out much this trend has permeated different societies, yet the overarching trend is there regardless of the degree of effect.

I think we have past the point of productive participation into territories of counterproductive participation. Most of the topics lack objectivity, thus inducing the chaotic nature of the collective consciousness and participation. It’s always worth considering the following two points when you consciously decide whether to participate and how much time you want to spend on any given topic.

Is my participation productive for the collective? Does it bring something new? Does the collective need my voice to be heard?

Is my participation productive for myself, the individual? Do I learn something new? Do I need to learn this new thing? Do I need my voice to be heard?

There is a lot of depth regarding the role of ego in questioning whether participation is worthwhile. I’m not going to discuss it here. Maybe some other time if the opportunity presents itself.

I’m not certain whether my intuition should be trusted here, since this is definitely the kind of thing my brain would form a habit of rationalizing about. But my guess is that I would’ve been way worse off without phones/social media/stuff. I didn’t really have any great alternatives to socializing on the internet—the only people I ever interacted with in person were devout Christians.

So I tentatively think it might be better to really focus on the improving alternatives part first? I’m sure I would’ve been much better off if I had good in-person friends, but I don’t think not having access to social media would have really helped with that, it’d just have meant I wouldn’t have any good friends at all.