LLM Generality is a Timeline Crux

Four-Month Update

[EDIT: I believe that this paper looking at o1-preview, which gets much better results on both blocksworld and obfuscated blocksworld, should update us significantly toward LLMs being capable of general reasoning. See update post here.]

Short Summary

LLMs may be fundamentally incapable of fully general reasoning, and if so, short timelines are less plausible.

Longer summary

There is ML research suggesting that LLMs fail badly on attempts at general reasoning, such as planning problems, scheduling, and attempts to solve novel visual puzzles. This post provides a brief introduction to that research, and asks:

Whether this limitation is illusory or actually exists.

If it exists, whether it will be solved by scaling or is a problem fundamental to LLMs.

If fundamental, whether it can be overcome by scaffolding & tooling.

If this is a real and fundamental limitation that can’t be fully overcome by scaffolding, we should be skeptical of arguments like Leopold Aschenbrenner’s (in his recent ‘Situational Awareness’) that we can just ‘follow straight lines on graphs’ and expect AGI in the next few years.

Introduction

Leopold Aschenbrenner’s recent ‘Situational Awareness’ document has gotten considerable attention in the safety & alignment community. Aschenbrenner argues that we should expect current systems to reach human-level given further scaling[1], and that it’s ‘strikingly plausible’ that we’ll see ‘drop-in remote workers’ capable of doing the work of an AI researcher or engineer by 2027. Others hold similar views.

Francois Chollet and Mike Knoop’s new $500,000 prize for beating the ARC benchmark has also gotten considerable recent attention in AIS[2]. Chollet holds a diametrically opposed view: that the current LLM approach is fundamentally incapable of general reasoning, and hence incapable of solving novel problems. We only imagine that LLMs can reason, Chollet argues, because they’ve seen such a vast wealth of problems that they can pattern-match against. But LLMs, even if scaled much further, will never be able to do the work of AI researchers.

It would be quite valuable to have a thorough analysis of this question through the lens of AI safety and alignment. This post is not that[3], nor is it a review of the voluminous literature on this debate (from outside the AIS community). It attempts to briefly introduce the disagreement, some evidence on each side, and the impact on timelines.

What is general reasoning?

Part of what makes this issue contentious is that there’s not a widely shared definition of ‘general reasoning’, and in fact various discussions of this use various terms. By ‘general reasoning’, I mean to capture two things. First, the ability to think carefully and precisely, step by step. Second, the ability to apply that sort of thinking in novel situations[4].

Terminology is inconsistent between authors on this subject; some call this ‘system II thinking’; some ‘reasoning’; some ‘planning’ (mainly for the first half of the definition); Chollet just talks about ‘intelligence’ (mainly for the second half).

This issue is further complicated by the fact that humans aren’t fully general reasoners without tool support either. For example, seven-dimensional tic-tac-toe is a simple and easily defined system, but incredibly difficult for humans to play mentally without extensive training and/or tool support. Generalizations that are in-distribution for humans feel intuitively like tasks that any general intelligence should be able to do; generalizations that are out-of-distribution for humans don’t feel as though they ought to count.

How general are LLMs?

It’s important to clarify that this is very much a matter of degree. Nearly everyone was surprised by the degree to which the last generation of state-of-the-art LLMs like GPT-3 generalized; for example, no one I know of predicted that LLMs trained on primarily English-language sources would be able to do translation between languages. Some in the field argued as recently as 2020 that no pure LLM would ever able to correctly complete Three plus five equals. The question is how general they are.

Certainly state-of-the-art LLMs do an enormous number of tasks that, from a user perspective, count as general reasoning. They can handle plenty of mathematical and scientific problems; they can write decent code; they can certainly hold coherent conversations.; they can answer many counterfactual questions; they even predict Supreme Court decisions pretty well. What are we even talking about when we question how general they are?

The surprising thing we find when we look carefully is that they fail pretty badly when we ask them to do certain sorts of reasoning tasks, such as planning problems, that would be fairly straightforward for humans. If in fact they were capable of general reasoning, we wouldn’t expect these sorts of problems to present a challenge. Therefore it may be that all their apparent successes at reasoning tasks are in fact simple extensions of examples they’ve seen in their truly vast corpus of training data. It’s hard to internalize just how many examples they’ve actually seen; one way to think about it is that they’ve absorbed nearly all of human knowledge.

The weakman version of this argument is the Stochastic Parrot claim, that LLMs are executing relatively shallow statistical inference on an extremely complex training distribution, ie that they’re “a blurry JPEG of the web” (Ted Chiang). This view seems obviously false at this point (given that, for example, LLMs appear to build world models), but assuming that LLMs are fully general may be an overcorrection.

Note that this is different from the (also very interesting) question of what LLMs, or the transformer architecture, are capable of accomplishing in a single forward pass. Here we’re talking about what they can do under typical auto-regressive conditions like chat.

Evidence for generality

I take this to be most people’s default view, and won’t spend much time making the case. GPT-4 and Claude 3 Opus seem obviously be capable of general reasoning. You can find places where they hallucinate, but it’s relatively hard to find cases in most people’s day-to-day use where their reasoning is just wrong. But if you want to see the case made explicitly, see for example “Sparks of AGI” (from Microsoft, on GPT-4) or recent models’ performance on benchmarks like MATH which are intended to judge reasoning ability.

Further, there’s been a recurring pattern (eg in much of Gary Marcus’s writing) of people claiming that LLMs can never do X, only to be promptly proven wrong when the next version comes out. By default we should probably be skeptical of such claims.

One other thing worth noting is that we know from ‘The Expressive Power of Transformers with Chain of Thought’ that the transformer architecture is capable of general reasoning under autoregressive conditions. That doesn’t mean LLMs trained on next-token prediction learn general reasoning, but it means that we can’t just rule it out as impossible. [EDIT 10/2024: a new paper, ‘Autoregressive Large Language Models are Computationally Universal’, makes this even clearer, and furthermore demonstrates that it’s true of LLMs in particular].

Evidence against generality

The literature here is quite extensive, and I haven’t reviewed it all. Here are three examples that I personally find most compelling. For a broader and deeper review, see “A Survey of Reasoning with Foundation Models”.

Block world

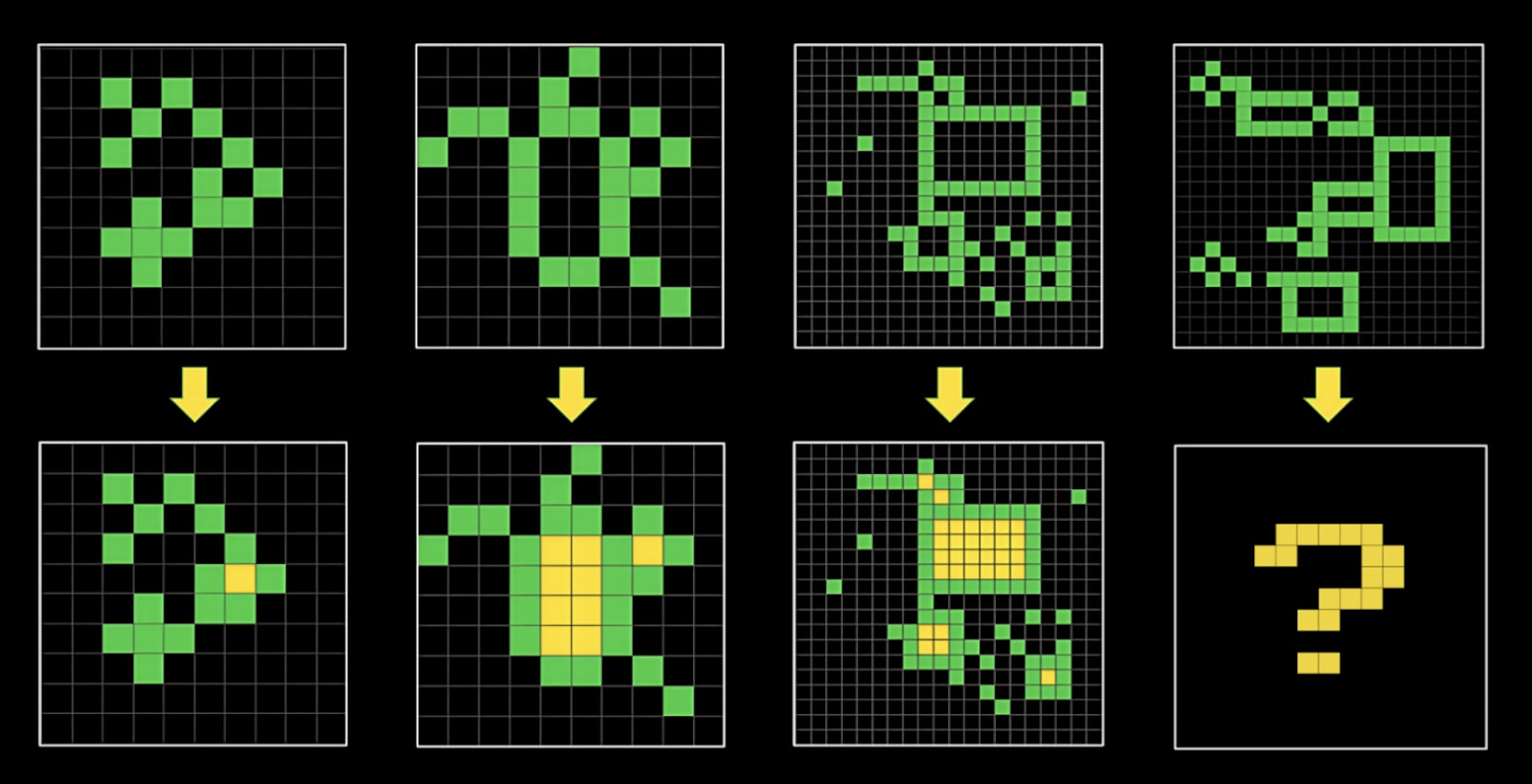

All LLMs to date fail rather badly at classic problems of rearranging colored blocks. We do see improvement with scale here, but if these problems are obfuscated, performance of even the biggest LLMs drops to almost nothing[5].

Scheduling

LLMs currently do badly at planning trips or scheduling meetings between people with availability constraints [a commenter points out that this paper has quite a few errors, so it should likely be treated with skepticism].

ARC-AGI

Current LLMs do quite badly on the ARC visual puzzles, which are reasonably easy for smart humans.

Will scaling solve this problem?

The evidence on this is somewhat mixed. Evidence that it will includes LLMs doing better on many of these tasks as they scale. The strongest evidence that it won’t is that LLMs still fail miserably on block world problems once you obfuscate the problems (to eliminate the possibility that larger LLMs only do better because they have a larger set of examples to draw from)[5].

One argument made by Sholto Douglas and Trenton Bricken (in a discussion with Dwarkesh Patel) is that this is a simple matter of reliability—given a 5% failure rate, an AI will most often fail to successfully execute a task that requires 15 correct steps. If that’s the case, we have every reason to believe that further scaling will solve the problem.

Will scaffolding or tooling solve this problem?

This is another open question. It seems natural to expect that LLMs could be used as part of scaffolded systems that include other tools optimized for handling general reasoning (eg classic planners like STRIPS), or LLMs can be given access to tools (eg code sandboxes) that they can use to overcome these problems. Ryan Greenblatt’s new work on getting very good results on ARC with GPT-4o + a Python interpreter provides some evidence for this.

On the other hand, a year ago many expected scaffolds like AutoGPT and BabyAGI to result in effective LLM-based agents, and many startups have been pushing in that direction; so far results have been underwhelming. Difficulty with planning and novelty seems like the most plausible explanation.

Even if tooling is sufficient to overcome this problem, outcomes depend heavily on the level of integration and performance. Currently for an LLM to make use of a tool, it has to use a substantial number of forward passes to describe the call to the tool, wait for the tool to execute, and then parse the response. If this remains true, then it puts substantial constraints on how heavily LLMs can rely on tools without being too slow to be useful[6]. If, on the other hand, such tools can be more deeply integrated, this may no longer apply. Of course, even if it’s slow there are some problems where it’s worth spending a large amount of time, eg novel research. But it does seem like the path ahead looks somewhat different if system II thinking remains necessarily slow & external.

Why does this matter?

The main reason that this is important from a safety perspective is that it seems likely to significantly impact timelines. If LLMs are fundamentally incapable of certain kinds of reasoning, and scale won’t solve this (at least in the next couple of orders of magnitude), and scaffolding doesn’t adequately work around it, then we’re at least one significant breakthrough away from dangerous AGI—it’s pretty hard to imagine an AI system executing a coup if it can’t successfully schedule a meeting with several of its co-conspirator instances.

If, on the other hand, there is no fundamental blocker to LLMs being able to do general reasoning, then Aschenbrenner’s argument starts to be much more plausible, that another couple of orders of magnitude can get us to the drop-in AI researcher, and once that happens, further progress seems likely to move very fast indeed.

So this is an area worth keeping a close eye on. I think that progress on the ARC prize will tell us a lot, now that there’s half a million dollars motivating people to try for it. I also think the next generation of frontier LLMs will be highly informative—it’s plausible that GPT-4 is just on the edge of being able to effectively do multi-step general reasoning, and if so we should expect GPT-5 to be substantially better at it (whereas if GPT-5 doesn’t show much improvement in this area, arguments like Chollet’s and Kambhampati’s are strengthened).

OK, but what do you think?

[EDIT: see update post for revised versions of these estimates]

I genuinely don’t know! It’s one of the most interesting and important open questions about the current state of AI. My best guesses are:

LLMs continue to do better at block world and ARC as they scale: 75%

LLMs entirely on their own reach the grand prize mark on the ARC prize (solving 85% of problems on the open leaderboard) before hybrid approaches like Ryan’s: 10%

Scaffolding & tools help a lot, so that the next gen[7] (GPT-5, Claude 4) + Python + a for loop can reach the grand prize mark[8]: 60%

Same but for the gen after that (GPT-6, Claude 5): 75%

The current architecture, including scaffolding & tools, continues to improve to the point of being able to do original AI research: 65%, with high uncertainty[9]

Further reading

Foundational Challenges in Assuring Alignment and Safety of Large Language Models, 04⁄24

Language Models Are Greedy Reasoners: A Systematic Formal Analysis of Chain-of-Thought 10⁄22

Finding Backward Chaining Circuits in Transformers Trained on Tree Search 05⁄24

Faith and Fate: Limits of Transformers on Compositionality, 05⁄23

Papers from Kambhampati’s lab, including

NATURAL PLAN: Benchmarking LLMs on Natural Language Planning, 06⁄24

What Algorithms can Transformers Learn? A Study in Length Generalization, 10⁄23

ARC prize, 06⁄24 and On the Measure of Intelligence, 11⁄19

See also Chollet’s recent appearance on Dwarkesh Patel’s podcast.

Large Language Models Cannot Self-Correct Reasoning Yet, 10⁄23

- ^

Aschenbrenner also discusses ‘unhobbling’, which he describes as ‘fixing obvious ways in which models are hobbled by default, unlocking latent capabilities and giving them tools, leading to step-changes in usefulness’. He breaks that down into categories here. Scaffolding and tooling I discuss here; RHLF seems unlikely to help with fundamental reasoning issues. Increased context length serves roughly as a kind of scaffolding for purposes of this discussion. ‘Posttraining improvements’ is too vague to really evaluate. But note that his core claim (the graph here) ‘shows only the scaleup in base models; “unhobblings” are not pictured’.

- ^

Discussion of the ARC prize in the AIS and adjacent communities includes James Wilken-Smith, O O, and Jacques Thibodeaux.

- ^

Section 2.4 of the excellent “Foundational Challenges in Assuring Alignment and Safety of Large Language Models” is the closest I’ve seen to a thorough consideration of this issue from a safety perspective. Where this post attempts to provide an introduction, “Foundational Challenges” provides a starting point for a deeper dive.

- ^

This definition is neither complete nor uncontroversial, but is sufficient to capture the range of practical uncertainty addressed below. Feel free to mentally substitute ‘the sort of reasoning that would be needed to solve the problems described here.’ Or see my more recent attempt at a definition.

- ^

A major problem here is that they obfuscated in ways that made the challenge unnecessarily hard for LLMs by pushing against the grain of the English language. For example they use ‘pain object’ as a fact, and say that an object can ‘feast’ another object. Beyond that, the fully-obfuscated versions would be nearly incomprehensible to a human as well; eg ‘As initial conditions I have that, aqcjuuehivl8auwt object a, aqcjuuehivl8auwt object b...object b 4dmf1cmtyxgsp94g object c...‘. See Appendix 1 in ‘On the Planning Abilities of Large Language Models’. It would be valuable to repeat this experiment while obfuscating in ways that were compatible with what is, after all, LLMs’ deepest knowledge, namely how the English language works.

- ^

A useful intuition pump here might be the distinction between data stored in RAM and data swapped out to a disk cache. The same data can be retrieved in either case, but the former case is normal operation, whereas the latter case is referred to as “thrashing” and grinds the system nearly to a halt.

- ^

Assuming roughly similar compute increase ratio between gens as between GPT-3 and GPT-4.

- ^

This isn’t trivially operationalizable, because it’s partly a function of how much runtime compute you’re willing to throw at it. Let’s say a limit of 10k calls per problem.

- ^

This isn’t really operationalizable at all, I don’t think. But I’d have to get pretty good odds to bet on it anyway; I’m neither willing to buy nor sell at 65%. Feel free to treat as bullshit since I’m not willing to pay the tax ;)

- LLMs Look Increasingly Like General Reasoners by (8 Nov 2024 23:47 UTC; 94 points)

- Numberwang: LLMs Doing Autonomous Research, and a Call for Input by (16 Jan 2025 17:20 UTC; 71 points)

- Will LLM agents become the first takeover-capable AGIs? by (2 Mar 2025 17:15 UTC; 37 points)

- Computational Complexity as an Intuition Pump for LLM Generality by (25 Jun 2024 20:25 UTC; 18 points)

- 's comment on Surprising LLM reasoning failures make me think we still need qualitative breakthroughs for AGI by (21 Apr 2025 18:57 UTC; 5 points)

- 's comment on Are LLMs on the Path to AGI? by (16 Sep 2024 20:14 UTC; 4 points)

Looking back at this post 18 months later, it’s making two distinct claims:

Whether LLMs are capable of general reasoning has strong implications for timelines.

We should be unsure whether LLMs are capable of general reasoning.

Point 1 stands. Point 2 was true at the time of publication, and is still somewhat true now, but I think the evidence that LLMs are capable of general reasoning is significantly stronger. Essentially all of the specific skeptical evidence I found most compelling in this post no longer held for frontier models four months later. The best-known LLM skeptics don’t seem to have updated much; see Gary Marcus’s blog for examples of this stance. I think there’s been a fair amount of goalpost-moving and a tendency to selectively focus on the negative evidence.

This became the first post of the ‘General Reasoning in LLMs’ sequence. I still owe a final post in that sequence, reporting the outcomes of empirical work on this question, which found that LLMs were capable of characterizing toy, novel scientific domains (up to some level of complexity, and not that reliably)

Of course, there are limits to LLM generalization, just as there are limits to human generalization. These are somewhat hard to cleanly specify, since as far as I know there’s still no good account of what counts as in- and out-of-distribution for LLM training data (please correct me!). But the pattern has been that when skeptics point to a specific missing capability that (in their view) shows that obviously LLMs are just shallow stochastic parrots, that capability is usually present in the next generation of models.

Interestingly, looking back at ARC-AGI while writing the review, I notice that Gemini-3 Deep Think has quietly crossed the winning threshold (85%) on the original ARC-AGI without that getting much notice. Of course it’s a big closed-source model, so not eligible for the grand prize. But it’s fascinating to compare to Chollet & Knoop’s original prediction that LLM-based approaches would stall out far below that: