Transformers Represent Belief State Geometry in their Residual Stream

Produced while being an affiliate at PIBBSS[1]. The work was done initially with funding from a Lightspeed Grant, and then continued while at PIBBSS. Work done in collaboration with @Paul Riechers, @Lucas Teixeira, @Alexander Gietelink Oldenziel, and Sarah Marzen. Paul was a MATS scholar during some portion of this work. Thanks to Paul, Lucas, Alexander, Sarah, and @Guillaume Corlouer for suggestions on this writeup.

Update May 24, 2024: See our manuscript based on this work

Introduction

What computational structure are we building into LLMs when we train them on next-token prediction? In this post we present evidence that this structure is given by the meta-dynamics of belief updating over hidden states of the data-generating process. We’ll explain exactly what this means in the post. We are excited by these results because

We have a formalism that relates training data to internal structures in LLMs.

Conceptually, our results mean that LLMs synchronize to their internal world model as they move through the context window.

The computation associated with synchronization can be formalized with a framework called Computational Mechanics. In the parlance of Computational Mechanics, we say that LLMs represent the Mixed-State Presentation of the data generating process.

The structure of synchronization is, in general, richer than the world model itself. In this sense, LLMs learn more than a world model.

We have increased hope that Computational Mechanics can be leveraged for interpretability and AI Safety more generally.

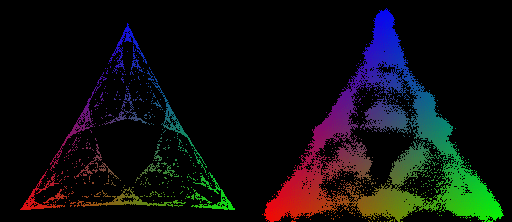

There’s just something inherently cool about making a non-trivial prediction—in this case that the transformer will represent a specific fractal structure—and then verifying that the prediction is true. Concretely, we are able to use Computational Mechanics to make an a priori and specific theoretical prediction about the geometry of residual stream activations (below on the left), and then show that this prediction holds true empirically (below on the right).

Theoretical Framework

In this post we will operationalize training data as being generated by a Hidden Markov Model (HMM)[2]. An HMM has a set of hidden states and transitions between them. The transitions are labeled with a probability and a token that it emits. Here are some example HMMs and data they generate.

Consider the relation a transformer has to an HMM that produced the data it was trained on. This is general—any dataset consisting of sequences of tokens can be represented as having been generated from an HMM. Through the discussion of the theoretical framework, let’s assume a simple HMM with the following structure, which we will call the Z1R process[3] (for “zero one random”).

The Z1R process has 3 hidden states, and . Arrows of the form denote , that the probability of moving to state and emitting the token , given that the process is in state , is . In this way, taking transitions between the states stochastically generates binary strings of the form ...01R01R... where R is a random 50⁄50 sample from {0, 1}.

The HMM structure is not directly given by the data it produces. Think of the difference between the list of strings this HMM emits (along with their probabilities) and the hidden structure itself[4]. Since the transformer only has access to the strings of emissions from this HMM, and not any information about the hidden states directly, if the transformer learns anything to do with the hidden structure, then it has to do the work of inferring it from the training data.

What we will show is that when they predict the next token well, transformers are doing even more computational work than inferring the hidden data generating process!

Do Transformers Learn a Model of the World?

One natural intuition would be that the transformer must represent the hidden structure of the data-generating process (ie the “world”[2]). In this case, this would mean the three hidden states and the transition probabilities between them.

This intuition often comes up (and is argued about) in discussions about what LLM’s “really understand.” For instance, Ilya Sutskever has said:

Because if you think about it, what does it mean to predict the next token well enough? It’s actually a much deeper question than it seems. Predicting the next token well means that you understand the underlying reality that led to the creation of that token. It’s not statistics. Like it is statistics but what is statistics? In order to understand those statistics to compress them, you need to understand what is it about the world that creates this set of statistics.

This type of intuition is natural, but it is not formal. Computational Mechanics is a formalism that was developed in order to study the limits of prediction in chaotic and other hard-to-predict systems, and has since expanded to a deep and rigorous theory of computational structure for any process. One of its many contributions is in providing a rigorous answer to what structures are necessary to perform optimal prediction. Interestingly, Computational Mechanics shows that prediction is substantially more complicated than generation. What this means is that we should expect a transformer trained to predict the next token well should have more structure than the data generating process!

The Structure of Belief State Updating

But what is that structure exactly?

Imagine you know, exactly, the structure of the HMM that produces ...01R... data. You go to sleep, you wake up, and you see that the HMM has emitted a 1. What state is the HMM in now? It is possible to generate a 1 both from taking the deterministic transition or from taking the stochastic transition . Since the deterministic transition is twice as likely as the 50% one, the best you can do is to have some belief distribution over the current states of the HMM, in the case [5].

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1... | |

| P() | |||||

| P() | |||||

| P() |

If now you see another 1 emitted, so that in total you’ve seen 11, you can now use your previous belief about the HMM state (read: prior), and your knowledge of the HMM structure alongside the emission you just saw (read: likelihood), in order to generate a new belief state (read: posterior). An exercise for the reader: What is the equation for updating your belief state given a previous belief state, an observed token, and the transition matrix of the ground-truth HMM?[6] In this case, there is only one way for the HMM to generate 11, , so you know for certain that the HMM is now in state . From now on, whenever you see a new symbol, you will know exactly what state the HMM is in, and we say that you have synchronized to the HMM.

In general, as you observe increasing amounts of data generated from the HMM, you can continually update your belief about the HMM state. Even in this simple example there is non-trivial structure in these belief updates. For instance, it is not always the case that seeing 2 emissions is enough to synchronize to the HMM. If instead of 11... you saw 10... you still wouldn’t be synchronized, since there are two different paths through the HMM that generate 10.

The structure of belief-state updating is given by the Mixed-State Presentation.

The Mixed-State Presentation

Notice that just as the data-generating structure is an HMM—at a given moment the process is in a hidden state, then, given an emission, the process move to another hidden state—so to is your belief updating! You are in some belief state, then given an emission that you observe, you move to some other belief state.

| Data Generating Process | Belief State Process | |

|---|---|---|

| States belong to | The data generating mechanism | The observer of the outputs of the data generating process |

| States are | Sets of sequences that constrain the future in particular ways | The observer’s beliefs over the states of the data generating process |

| Sequences of hidden states emit | Valid sequences of data | Valid sequences of data |

| Interpretation of emissions | The observables/tokens the data generating process emits | What the observer sees from the data generating process |

The meta-dynamics of belief state updating are formally another HMM, where the hidden states are your belief states. This meta-structure is called the Mixed-State Presentation (MSP) in Computational Mechanics.

Note that the MSP has transitory states (in green above) that lead to a recurrent set of belief states that are isomorphic to the data-generating process—this always happens, though there might be infinite transitory states. Synchronization is the process of moving through the transitory states towards convergence to the data-generating process.

A lesson from Computational Mechanics is that in order to perform optimal prediction of the next token based on observing a finite-length history of tokens, one must implement the Mixed-State Presentation (MSP). That is to say, to predict the next token well one should know what state the data-generating process is in as best as possible, and to know what state the data-generating process is in, implement the MSP.

The MSP has a geometry associated with it, given by plotting the belief-state values on a simplex. In general, if our data generating process has N states, then probability distributions over those states will have degrees of freedom, and since all probabilities must be between 0 and 1, all possible belief distributions lie on an simplex. In the case of Z1R, that means a 2-simplex (i.e. a triangle). We can plot each of our possible belief states in this 2-simplex, as shown on the right below.

What we show in this post is that when we train a transformer to do next token prediction on data generated from the 3-state HMM, we can find a linear representation of the MSP geometry in the residual stream. This is surprising! Note that the points on the simplex, the belief states, are not the next token probabilities. In fact, multiple points here have literally the same next token predictions. In particular, in this case, , , and , all have the same optimal next token predictions.

Another way to think about this claim is that transformers keep track of distinctions in anticipated distribution over the entire future, beyond distinctions in next token predictions, even though the transformer is only trained explicitly on next token prediction! That means the transformer is keeping track of extra information than what is necessary just for the local next token prediction.

Another way to think about our claim is that transformers perform two types of inference: one to infer the structure of the data-generating process, and another meta-inference to update it’s internal beliefs over which state the data-generating process is in, given some history of finite data (ie the context window). This second type of inference can be thought of as the algorithmic or computational structure of synchronizing to the hidden structure of the data-generating process.

A final theoretical note about Computational Mechanics and the theory presented here: because Computational Mechanics is not contingent on the specifics of transformer architectures and is a well-developed first-principles framework, we can apply this framework to any optimal predictor, not just transformers[7].

Experiment and Results

Experimental Design

To repeat the question we are trying to answer:

What computational structure are we building into LLMs when we train them on next-token prediction?

To test our theoretical predictions, we designed an experiment with the following steps:

Generate training data from a known HMM structure, specifically the 3-state HMM described in the “Data-Generating Process and MSP” section below.

Train a transformer on this data to perform next-token prediction. In the experiments shown here we use a 4-layer transformer with 64 dimensional residual stream, and 4 attention heads per layer.

Analyze the final layer of the transformer’s residual stream to look for a linear subspace with a geometry matching the predicted fractal structure of the Mixed-State Presentation (MSP).

By controlling the structure of the training data using an HMM, we can make concrete, falsifiable predictions about the computational structure the transformer should implement during inference. Computational Mechanics, as presented in the “Theoretical Framework” section above, provides the framework for making these predictions based on the HMM’s structure.

The specific HMM we chose has an MSP with an infinite fractal geometry, serving as a highly non-trivial prediction about what we should find in the transformer’s residual stream activations if our theory is correct.

The Data-Generating Process and MSP

For this experiment we trained a transformer on data generated by a simple HMM, called the Mess3 Process, that has just 3 hidden states[8]. Moving between the 3 hidden states according to the emission probabilities on the edges generates strings over a 3-token vocabulary: {A, B, C}. The HMM for this data-generating process is given on the left of the figure below.

Our approach allows us to make rigorous and testable predictions about the internal structures of transformers. In the case of this HMM, the theory (outlined above) says that transformers trained on this data should instantiate the computational structure associated with the fractal geometry shown on the right of the figure above. Every colored point in the simplex on the above right panel is a distinct belief state.

We chose the Mess3 HMM because it’s MSP has an infinite fractal structure, and thus acts as a highly-nontrivial prediction about what geometry we should find in the residual stream.

The Results!

We train a transformer on data generated by the Mess3 HMM. We look in the final layer of the residual stream and find a linear 2D subspace where activations have a structure remarkably similar to that of our predicted fractal. We do this by performing standard linear regression from the residual stream activations (64 dimensional vectors) to the belief distributions (3 dimensional vectors) which associated with them in the MSP.

We can also look at how this structure emerges over training, which shows (1) that the structure we find is not trivial[9] since it doesn’t exist in detail early in training, and (2) the step-wise refinement of the transformers activations to the fractal structure we predict.

A movie of this process is shown below. Because we used Stochastic Gradient Descent for training, the 2D projection of the activations wiggles, even after training has converged. In this wiggling you can see that fractal structures remain intact.

Limitations and Next Steps

Limitations

Presented here was one simple data structure given by an HMM with 3 states, with a vocab size of 3. In practice, the LLMs that currently exist are much larger, have vocab sizes of >50,000, and natural language has infinite Markov order. Though we’ve tested this theory on other HMMs and everything continues to work, all tests so far have been on similarly small examples. How this relates to larger, more complicated, and more realistic settings is unknown (but we have ideas!).

Though we haven’t focused on it in this post, the MSP is an input-driven dynamical system. For each possible input in the system, we have dynamics that determine where in the belief simplex one should move to given the current belief. We have not explicitly tested that the LLM instantiates these dynamics, and instead have only tested that the belief states and their geometry is represented in the transformer.

Computational Mechanics is primarily a story about optimal prediction. LLMs in practice won’t be literally optimal. A number of papers exist studying near-optimality, non-optimality, and rate-distortion phenomenon from the point of view of Computational Mechanics, but applying that to LLMs has not been done.

We have focused on ergodic and stationary processes in the work presented here. Computational Mechanics can relax those assumptions, but again, we have not applied those (very interesting!) extensions of Computational Mechanics to LLMs. Non-ergodicity, in particular, is likely at the heart of in-context learning.

In the experiment presented in this post we focussed on the final layer of the residual stream, right before the unembedding. In other experiments we’ve run (not presented here), the MSP is not well-represented in the final layer but is instead spread out amongst earlier layers. We think this occurs because in general there are groups of belief states that are degenerate in the sense that they have the same next-token distribution. In that case, the formalism presented in this post says that even though the distinction between those states must be represented in the transformers internal, the transformer is able to lose those distinctions for the purpose of predicting the next token (in the local sense), which occurs most directly right before the unembedding.

Next Steps

We are hopeful that the framing presented in this post provides a formal handle on data structure, internal network structure, and network behavior.

There are many open questions about how this work relates to other technical AI Safety work. I’ll list a few ideas very quickly, and expand on these and more in future posts. In particular:

What is the relationship between features and circuits, as studied in Mechanistic Interpretability, and the Mixed-State Geometry?

Is there a story about superposition and compression of the MSP in cases where the residual stream is too small to “fit” the MSP.

Can we relate the development of MSP geometric structure over training to phenomenon in SLT? see Towards Developmental Interpretability

Can we use our formalism to operationalize particular capabilities (in-context learning, out-of-distribution generalization, situational awareness, sleeper agents, etc.) and study them in toy models from our framework?

Can we use our formalism to understand task structure and how distinct tasks relate to each other? see A starting point for making sense of task structure (in machine learning)

As mentioned in the Limitations section, how MSP structures in transformers divide across the layers of the transformer, and how the functional form of the attention mechanism relates to that is an obvious next step.

We will be releasing a python library soon to be able to perform these types of experiments. Here is the github repo.

Computational Mechanics is a well-developed framework, and this post has only focused on one small section of it. In the future we hope to bring other aspects of it to bear on neural networks and safety issues, and also to expand Computational Mechanics and combine it with other methods and frameworks.

If you’re interested in learning more about Computational Mechanics, we recommend starting with these papers: Shalizi and Crutchfield (2000), Riechers and Crutchfield (2018a), and Riechers and Crutchfield (2018b)

We (Paul and Adam) have received funding to start a new AI Safety research org, called Simplex! Presented here was one small facet of the type of work we hope to do, and very much only the beginning. Stay tuned for posts that outline our broader vision in the future.

In about a month we will be teaming up with Apart to run a Hackathon! We will post about that soon as well, alongside an open problems post, and some more resources to run experiments.

There’s a lot of work to do going forward! This research plan has many parts that span the highly mathematical/theoretical to experimental. If you are interested in being a part of this please have a low threshold for reaching out!

- ^

PIBBSS is hiring! I wholeheartedly recommend them as an organization.

- ^

One way to conceptualize this is to think of “the world” as having some hidden structure (initially unknown to you), that emits observables. Our task is then to take sequences of observables and infer the hidden structure of the world—maybe in the service of optimal future prediction, but also maybe just because figuring out how the world works is inherently interesting. Inside of us, we have a “world model” that serves as the internal structure that let’s us “understand” the hidden structure of the world. The term world model is contentious and nothing in this post depends on that concept much. However, one motivation for this work is to formalize and make concrete statements about peoples intuitions and arguments regarding neural networks and world models—which are often handwavy and ill-defined.

- ^

Technically speaking, the term process refers to a probability distribution over infinite strings of tokens, while a presentation refers to a particular HMM that produces strings according to the probability distribution. A process has an infinite number of presentations.

- ^

Any HMM defines a probability distribution over infinite sequences of the emissions.

- ^

Our initial belief distribution, in this particular case, is the uniform distribution over the 3 states of the data generating process. However this is not always the case. In general the initial belief distribution is given by the stationary distribution of the data generating HMM.

- ^

You can find the answer in section IV of this paper by @Paul Riechers.

- ^

There is work in Computational Mechanics that studies non-optimal or near-optimal prediction, and the tradeoffs one incurs when relaxing optimality. This is likely relevant to neural networks in practice. See Marzen and Crutchfield 2021 and Marzen and Crutchfield 2014.

- ^

This process is called the mess3 process, and was defined in a paper by Sarah Marzen and James Crutchfield. In the work presented we use x=0.05, alpha=0.85.

- ^

We’ve also run another control where we retain the ground truth fractal structure but shuffle which inputs corresponds to which points in the simplex (you can think of this as shuffling the colors in the ground truth plot). In this case when we run our regression we get that every residual stream activation is mapped to the center point of the simplex, which is the center of mass of all the points.

- Shallow review of technical AI safety, 2024 by (29 Dec 2024 12:01 UTC; 202 points)

- Why Would Belief-States Have A Fractal Structure, And Why Would That Matter For Interpretability? An Explainer by (18 Apr 2024 0:27 UTC; 185 points)

- Announcing ILIAD — Theoretical AI Alignment Conference by (5 Jun 2024 9:37 UTC; 163 points)

- Language Models Model Us by (17 May 2024 21:00 UTC; 159 points)

- Why I funded PIBBSS by (15 Sep 2024 19:56 UTC; 115 points)

- Simplex Progress Report—July 2025 by (28 Jul 2025 21:58 UTC; 108 points)

- Why I funded PIBBSS by (EA Forum; 15 Sep 2024 19:56 UTC; 90 points)

- Announcing ILIAD2: ODYSSEY by (3 Apr 2025 17:01 UTC; 80 points)

- Renormalization Redux: QFT Techniques for AI Interpretability by (18 Jan 2025 3:54 UTC; 47 points)

- Deeper Reviews for the top 15 (of the 2024 Review) by (14 Jan 2026 23:59 UTC; 45 points)

- Mech Interp Lacks Good Paradigms by (16 Jul 2024 15:47 UTC; 40 points)

- Cross-context abduction: LLMs make inferences about procedural training data leveraging declarative facts in earlier training data by (16 Nov 2024 23:22 UTC; 36 points)

- AI in a vat: Fundamental limits of efficient world modelling for safe agent sandboxing by (1 Aug 2025 18:37 UTC; 34 points)

- Computational Mechanics Hackathon (June 1 & 2) by (24 May 2024 22:18 UTC; 34 points)

- 's comment on How We Picture Bayesian Agents by (10 Apr 2024 2:16 UTC; 30 points)

- AXRP Episode 36 - Adam Shai and Paul Riechers on Computational Mechanics by (29 Sep 2024 5:50 UTC; 25 points)

- 's comment on Double’s Shortform by (22 Jul 2025 15:16 UTC; 6 points)

- Towards Understanding the Representation of Belief State Geometry in Transformers by (18 Apr 2025 12:39 UTC; 5 points)

- 's comment on Getting 50% (SoTA) on ARC-AGI with GPT-4o by (17 Jun 2024 23:52 UTC; 4 points)

- 's comment on Ryan Kidd’s Shortform by (23 Dec 2025 18:36 UTC; 4 points)

- 's comment on KAN: Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks by (4 May 2024 3:36 UTC; 3 points)

- 's comment on Daniel Tan’s Shortform by (17 Jul 2024 7:39 UTC; 3 points)

- 's comment on LW Frontpage Experiments! (aka “Take the wheel, Shoggoth!”) by (2 May 2024 7:04 UTC; 2 points)

- 's comment on A quantum equivalent to Bayes’ rule by (2 Sep 2025 5:37 UTC; 2 points)

- 's comment on Daniel Tan’s Shortform by (17 Jul 2024 8:01 UTC; 1 point)

This is a self review. It’s been about 600 days since this was posted and I’m still happy and proud about this post. In terms of what I view as the important message to the readership, the main thing is introducing a framework and way of thinking that connects what is a pretty fuzzy notion of “world model” to the concrete internal structure of neural networks. It does this in a way that is both theoretically clear and amenable to experiments. It provides a way to think about representations in transformers in a general sense, that is quite different than the normal tactic taken in interpretability. One interesting thing given how interp has progressed since then, is that it provides a way to think about geometric structures in the activations of these networks, which is something the field seems to be moving towards (albeit not guided by theory the way this work is).

I spent a lot of time/effort on making the presentation both easy to follow while actually containing the important lessons. I feel this post does a great job at that. (and in fact, others around me were telling me I was taking too long and that I just needed to hit submit—I’m glad I didn’t follow that advice :)

This work has been expanded on in a number of directions (a recent post summarizes three of those direction). We now have Simplex, an entire org that would likely not exist in the way that it does without this post (we got seed funding right before this post, but the ability to fundraise and attract talent were highly dependent on this post)! We are ~10 people and expanding. Starting this org, watching it grow, being part of the building up of a new way to think about/do interpretability has been the greatest intellectual achievement of my life, and again, I do not think this would have occured (at least not the way it did), without this post.

Some of the things we are working on is extending the framework to more complicated (factorizable) generative structures, which gives way to both a very nice story explaining how it is neural nets can cram so much into their activations, and the corresponding geometric relationship to computational structure. We also have a team dedicated to red-teaming the theory and application to experiments in a number of ways, one of which is more precisely testing the distinction between representing next-token vs. far future representaitons. We are also looking for the types of geometric structures our theory predicts in LLMs, and building tools to do unsuprvised finding of these geometric structures in LLMs.

In retrospect there are a few things I would have emphasized or done differently. The most concrete one would have been to include experiments on RRXOR in this writeup, which more directly test/show representations that have information beyond the next token, and that are predicted by the theory.

Another regret is that I haven’t done a good job of keeping up with the public facing side of our work since this post. We made one post about our work since then, and it really does hide a lot of the insights we’ve made internally. This is not great, since I do believe that we have refined our way of thinking about representations and computations in these systems, in a way that the interp community needs.

More personally (and perhaps this isn’t relevant for a review since it really is just about me), this post came after switching fields from neuroscience, where I was for a decade, to interpretability. There was a lot of uncertainty and stress about that move, and quite a bit of wondering if I could actually contribute. So it was a big deal for me to see the community react positively to this work. Additionally, I had been interested in computational mechanics for a decade from within neuroscience, since it felt like it could say something about computation in biological neural nets, but I could never figure out how to get it to do anything useful. So it’s also a privilege to see the dream play out and be realized in neural nets, and to start a research org dedicated to that vision!

The start of the research program presented here is in a real sense a bet, in that it could fail to be useful at scale, for a few different reasons. But the fact that we are building up with both theory and experiment in a way where each informs the other, and that we were able to show the community a small part of what this looks like, is a lesson I hope the readership takes, even beyond the specific content of this post. (hot take) I think a lot of great work happens within this community, but too often the more theoretical and the more empirical approaches don’t talk to eachother as much as they should.