AI in 2025: gestalt

This is the editorial for this year’s “Shallow Review of AI Safety”. (It got long enough to stand alone.)

Epistemic status: subjective impressions plus one new graph plus 300 links.

Huge thanks to Jaeho Lee, Jaime Sevilla, and Lexin Zhou for running lots of tests pro bono and so greatly improving the main analysis.

tl;dr

Informed people disagree about the prospects for LLM AGI – or even just what exactly was achieved this year. But the famous ones with a book to talk at least agree that we’re 2-20 years off (allowing for other paradigms arising). In this piece I stick to arguments rather than reporting who thinks what.

My view: compared to last year, AI is much more impressive but not proportionally more useful. They improved on some things they were explicitly optimised for (coding, vision, OCR, benchmarks), and did not hugely improve on everything else. Progress is thus (still!) consistent with current frontier training bringing more things in-distribution rather than generalising very far.

Pretraining (GPT-4.5, Grok 3⁄4, but also the counterfactual large runs which weren’t done) disappointed people this year. It’s probably not because it didn’t or wouldn’t work; it was just too hard to serve the big models and ~30 times more efficient to do post-training instead, on the margin. This should change, yet again, soon, if RL scales even worse.

Edit: See this amazing comment for the hardware reasons behind this, and reasons to think that pretraining will struggle for years.

True frontier capabilities are likely obscured by systematic cost-cutting (distillation for serving to consumers, quantization, low reasoning-token modes, routing to cheap models, etc) and a few unreleased models/modes.

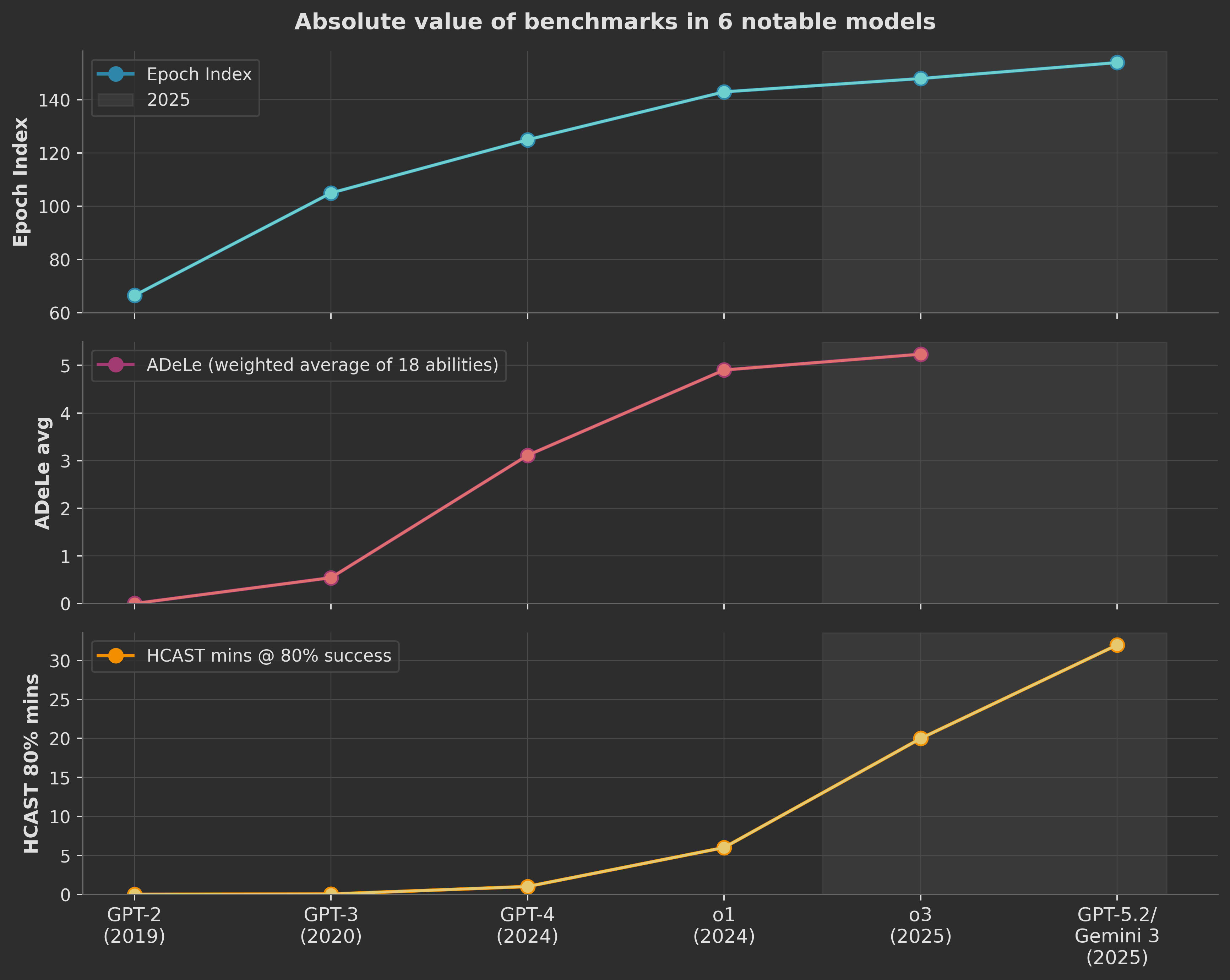

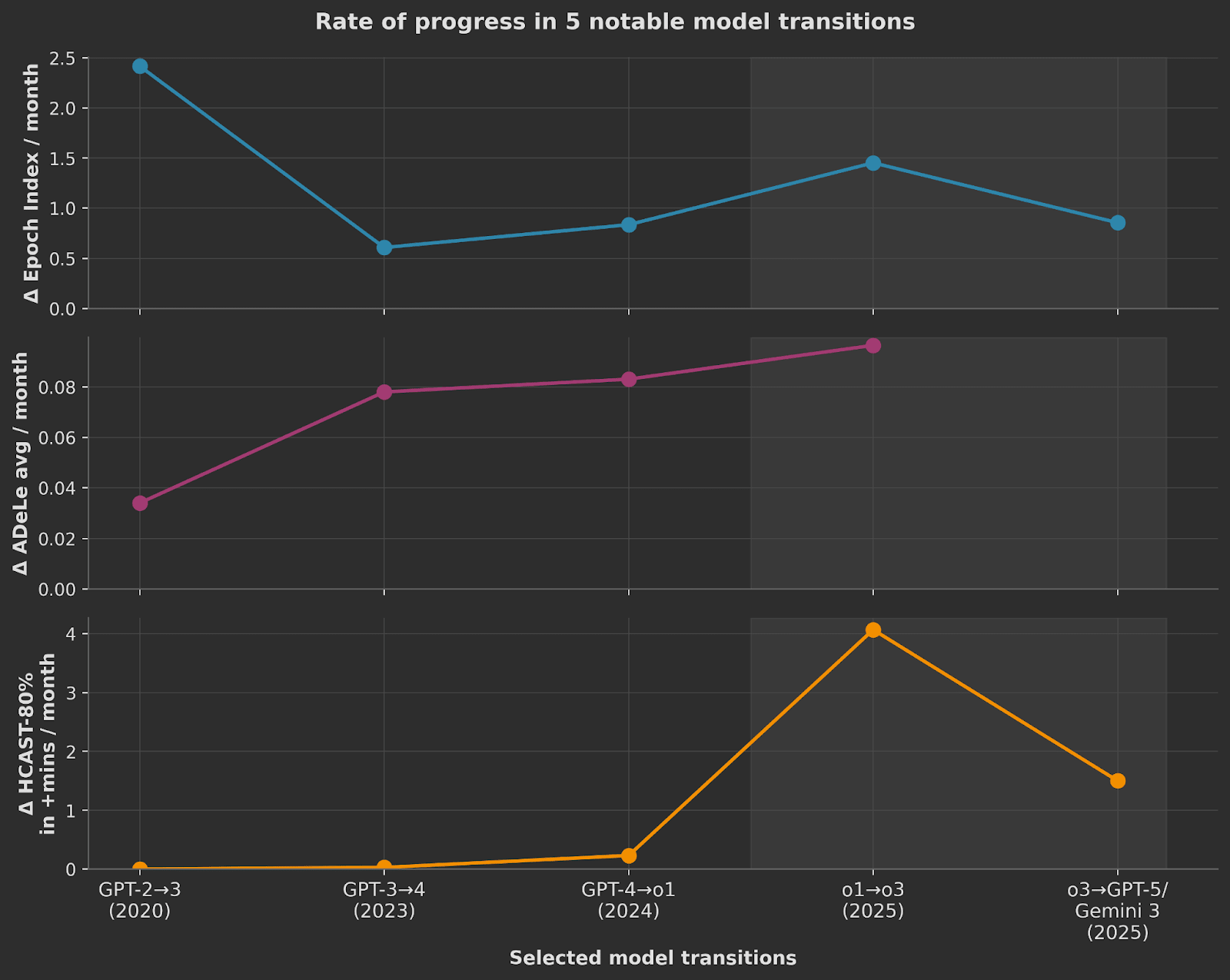

Most benchmarks are weak predictors of even the rank order of models’ capabilities. I distrust ECI, ADeLe, and HCAST the least. ECI shows a linear improvement, HCAST finds an exponential improvement on greenfield software engineering, and ADeLe shows a previous exponential+ slowing down to what might be linear growth since o1.

Using these three, I find that 2025 progress is as fast as the whole preceding LLM era. But these numbers aren’t enough to convince me.

The world’s de facto strategy remains “iterative alignment”, optimising outputs with a stack of alignment and control techniques everyone admits are individually weak.

Early claims that reasoning models are safer turned out to be a mixed bag (see below). Adversarial robustness is not improving much; practical improvements we see are due to external “safeguards” (auxiliary models).

We already knew from jailbreaks that current alignment methods were brittle. The great safety discovery of the year is that bad things are correlated in current models. (And on net this is good news.)

Previously I thought that “character training” was a separate and lesser matter than “alignment training”. Now I am not sure.

Welcome to the many new people in AI Safety and Security and Assurance and so on. In the Shallow Review, I added a new, sprawling top-level category for one large trend among them, which is to treat the multi-agent lens as primary in various ways.

Overall I wish I could tell you some number, the net expected safety change (this year’s improvements in dangerous capabilities and agent performance, minus the alignment-boosting portion of capabilities, minus the cumulative effect of the best actually implemented composition of alignment and control techniques). But I can’t.

Capabilities in 2025

Better, but how much?

Arguments against 2025 capabilities growth being above-trend

Apparent progress is an unknown mixture of real general capability increase, hidden contamination increase, benchmaxxing (nailing a small set of static examples instead of generalisation) and usemaxxing (nailing a small set of narrow tasks with RL instead of deeper generalisation). It’s reasonable to think it’s 25% each, with low confidence.

Discrete capabilities progress seems slower this year than in 2024 (but 2024 was insanely fast). Kudos to this person for registering predictions and so reminding us what really above-trend would have meant concretely. The excellent forecaster Eli was also over-optimistic in places.

I don’t recommend taking benchmark trends, or even clever composite indices of them, or even clever cognitive science measures too seriously. The adversarial pressure on the measures is intense.

Pretraining didn’t hit a “wall”, but the driver did manoeuvre away on encountering an easier detour (RLVR).

Training runs continued to scale (Llama 3 405B = 4e25, GPT-4.5 ~= 4e26, Grok 4 ~= 3e26) but to less effect.[1] In fact all of these models are dominated by apparently smaller pretraining runs with better post-training. 4.5 is actually off the API already.

In 2025 it wasn’t worth it to serve any giant model (i.e. ~4T total params), nor to make it into a reasoning model. But this is more to do with inference cost and inference hardware constraints than any quality shortfall or breakdown in scaling laws.

EDIT: Nesov notes that making use of bigger models (i.e. 4T parameters) is heavily bottlenecked on CoWoS and inference HBM, as is doing RL on bigger models. He expects it won’t be possible to do the next huge pretraining jump (to ~30T total) using NVIDIA until late ~2028. The Ironwood TPUs are a different matter and might be able to do it in late 2026.

It would work, probably, if we had the data and CoWoS and spent the next $10bn, it’s just too expensive to bother with at the moment compared to:

RLVR scaling and inference scaling (or “reasoning” as we’re calling it), which kept things going instead. This boils down to spending more on RL so the resulting model can productively spend more tokens.

But the feared / hoped-for generalisation from {training LLMs with RL on tasks with a verifier} to performing on tasks without one remains unclear even after two years of trying.[2] Grok 4 was apparently a major test of scaling RLVR training.[3] It gets excellent benchmark results and the distilled versions are actually being used at scale. But imo it is the most jagged of all models.

This rate of scaling-up cannot be sustained: RL is famously inefficient. Compared to SFT, it “reduces the amount of information a model can learn per hour of training by a factor of 1,000 to 1,000,000”. The per-token intelligence is up but not by much.

There is a deflationary theory of RLVR, that it’s capped by pretraining capability and thus just about easier elicitation and better pass@1. But even if that’s right this isn’t saying much!

RLVR is heavy fiddly R&D you need to learn by doing; better to learn it on smaller models with 10% of the cost.

An obvious thing we can infer: the labs don’t have the resources to scale both at the same time. To keep the money jet burning, they have to post models.

So pretraining can’t scale yet, because most inference chips aren’t big enough to handle trillions of active parameters. And scaling RL more won’t help as much as it helped this year, because of inefficiency. So…

By late 2025, the obsolete modal “AI 2027” scenario described the beginning of a divergence between the lead lab and the runner-up frontier labs.[4] This is because the leader’s superior ability to generate or acquire new training data and algorithm ideas was supposed to compound and widen their lead. Instead, we see the erstwhile leader OpenAI and some others clustering around the same level, which is weak evidence that synthetic data and AI-AI R&D aren’t there yet. Anthropic are making large claims about Opus 4.5’s capabilities, so maybe this will arrive on time next year.

For the first time there are now many examples of LLMs helping with actual research mathematics. But if you look closely it’s all still in-distribution in the broad sense: new implications of existing facts and techniques. (I don’t mean to demean this; probably most mathematics fits this spec.) And it’s almost never fully autonomous; there’s usually hundreds of bits of human steering.

Extremely mixed evidence on the trend in the hallucination rate.

Companies make claims about their one-million- or ten-million-token effective context windows, but I don’t believe it.

In lieu of trying the agents for serious work yourself, you could at least look at the highlights of the gullible and precompetent AIs in the AI Village.

Here are the current biggest limits to LLMs, as polled in Heitmann et al:

Arguments for 2025 capabilities growth being above-trend

We now have measures which are a bit more like AGI metrics than dumb single-task static benchmarks are. What do they say?

Difficulty-weighted benchmarks: Epoch Capabilities Index.

Interpretation: GPT-2 to GPT-3 was (very roughly) a 20-40 point jump.

Cognitive abilities: ADeLe.[5]

Interpretation: level L is the capability held by 1 in humans on Earth. GPT-2 to GPT-3 was a 0.6 point jump.

Software agency: HCAST time horizon, the ability to handle larger-scale well-specified greenfield software tasks.

Interpretation: the absolute values are less important than the implied exponential (a 7 month doubling time).

So: is the rate of change in 2025 (shaded) holding up compared to past jumps?:

Ignoring the (nonrobust)[6] ECI GPT-2 rate, we can say yes: 2025 is fast, as fast as ever, or more.

Even though these are the best we have, we can’t defer to these numbers.[7] What else is there?

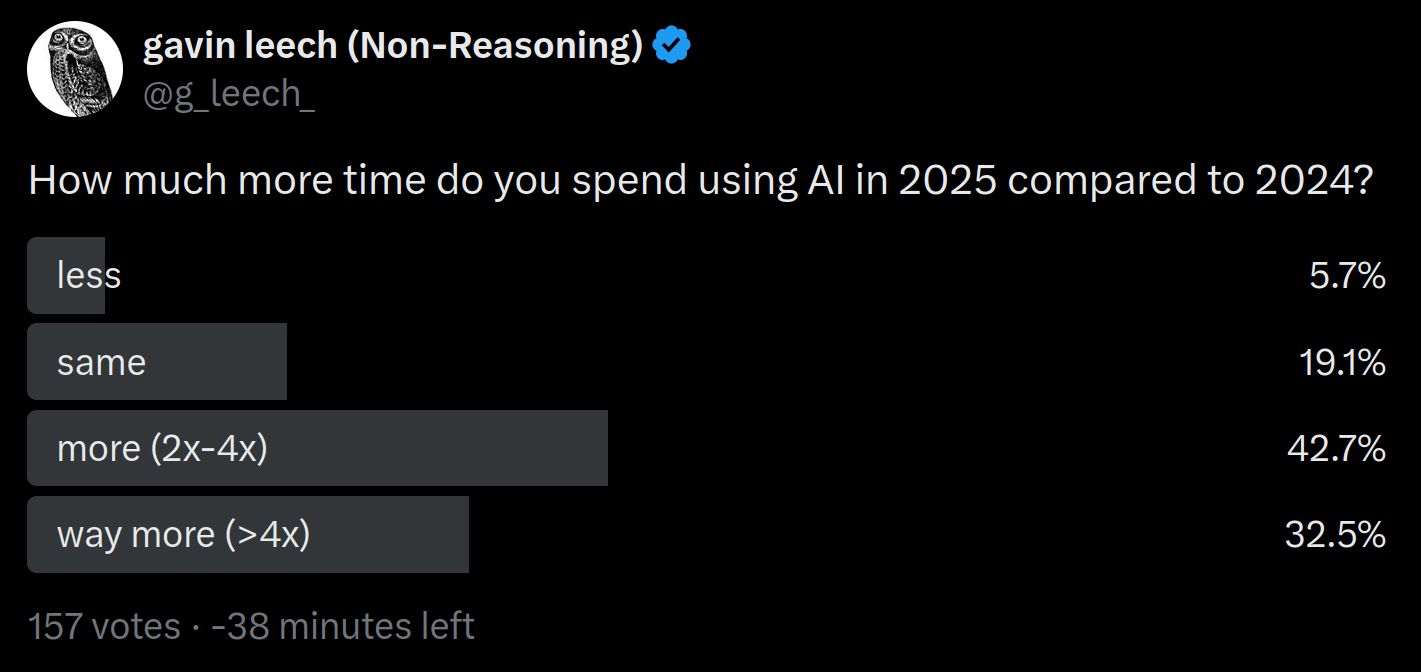

In May they passed some threshold and I finally started using LLMs for actual tasks. For me this is mostly due to the search agents replacing a degraded Google search. I‘m not the only one who flipped this year. This hasty poll is worth more to me than any benchmark:

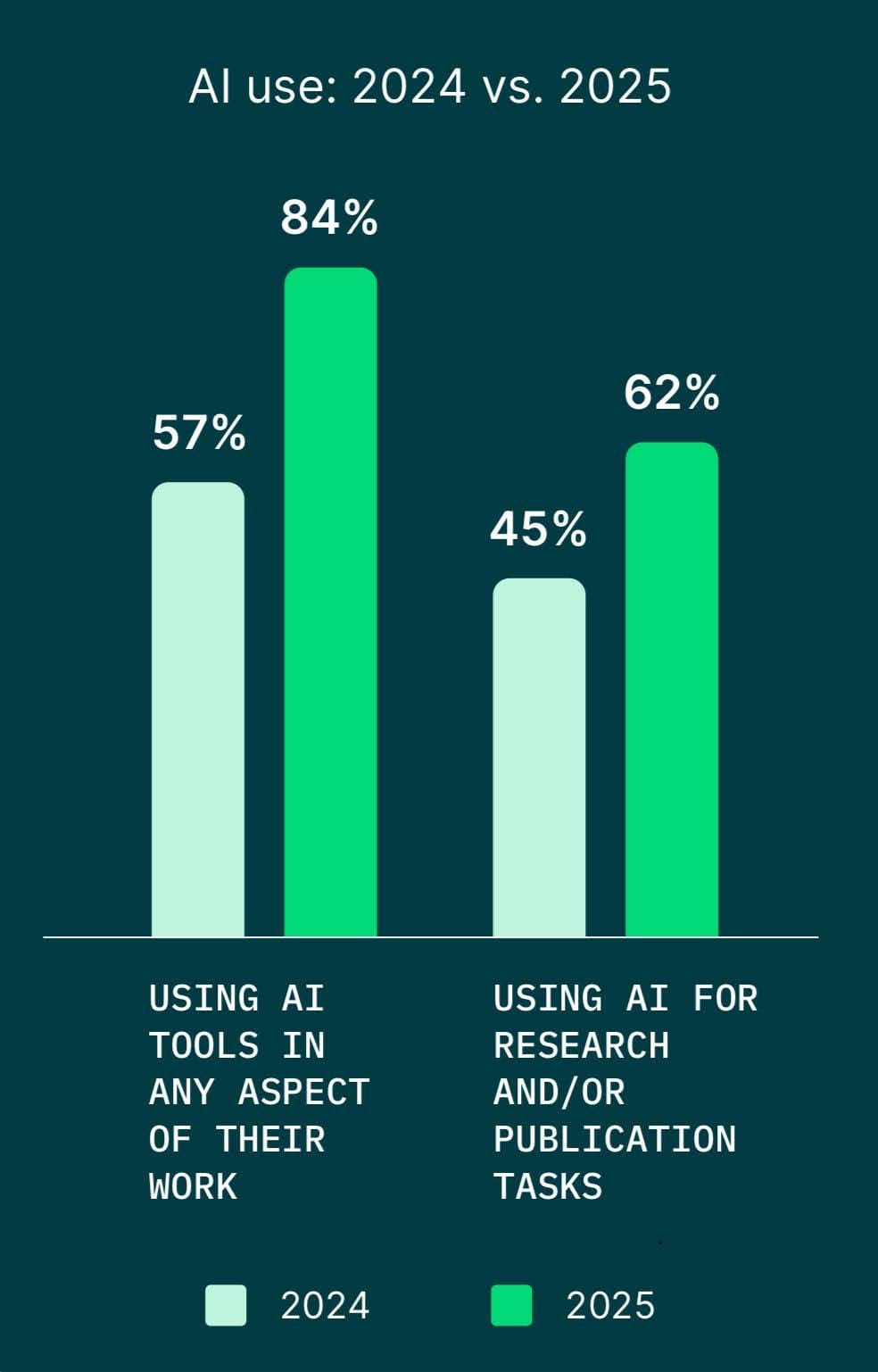

Or if you prefer a formal study (n=2,430 researchers):

On actual adoption and real-world automation:

Based on self-reports, the St Louis Fed thinks that “Between 1 and 7% of all work hours are currently assisted by generative AI, and respondents report time savings equivalent to 1.4% of total work hours… across all workers (including non-users… Our estimated aggregate productivity gain from genAI (1.2%)”. That’s model-based, using year-old data, and naively assuming that the AI outputs are of equal quality. Not strong.

The unfairly-derided METR study on Cursor and Sonnet 3.7 showed a productivity decrease among experienced devs with (mostly) <50 hours of practice using AI. Ignoring that headline result, the evergreen part here is that even skilled people turn out to be terrible at predicting how much AI actually helps them.

But, plainly, coding is just different now than it ever was in history, especially for people with low-to-no-skill.

True frontier capabilities are likely obscured by systematic cost-cutting (distillation for serving to consumers, quantization, low reasoning-token modes, routing to cheap models, etc). Open models show you can now get good performance with <50B active parameters, maybe a sixth of what GPT-4 used.[8]

GPT-4.5 was killed off after 3 months, presumably for inference cost reasons. But it was markedly lower in hallucinations and nine months later it’s still top-5 on LMArena. I bet it’s very useful internally, for instance in making the later iterations of 4o less terrible.

See for instance the unreleased deep-fried multi-threaded “experimental reasoning model” which won at IMO, ICPC, and IOI while respecting the human time cap (e.g. 9 hours of clock time for inference). The OpenAI one is supposedly just an LLM with extra RL. They probably cost an insane amount to run, but for our purposes this is fine: we want the capability ceiling rather than the productisable ceiling. Maybe the first time that the frontier model has gone unreleased for 5 months?

LLM councils and Generate-Verify divide-and-conquer setups are much more powerful than single models, and are rarely ever reported. I use Critch’s Multiplicity to poll and aggregate them in the browser.

Is it “the Year of Agents” (automation of e.g. browser tasks for the mass market)? Coding agents, yes. Search agents, yes. Other agents, not much (but obviously progress).

We’re still picking up various basic unhobbling tricks like “think before your next tool call”.

METR’s task-time-horizon work, if it implies anything, implies a faster rate of improvement than last year. There’s much to be said against this, and it has been said, including by METR.

“Deep Research” search agents only launched in December/February. They’re neither deep nor doing research, but useful.

I claim that instruction-following improved a lot. (Some middling evidence here.) This is a big deal: besides its relation to corrigibility, it also denotes general ability to infer intent and connotations.

Character-level tokenizer-based errors are still occasionally problematic but nothing like last year.

GPT-5 costs a quarter of what 4o cost last year (per-token; it often uses far more than 4x the tokens). (The Chinese models are nominally a few times cheaper still, but are not cheaper in intelligence per dollar.)

People have been using competition mathematics as a hard benchmark for years, but will have to stop because it’s solved. As so often with evals called ahead of time, this means less than we thought it would; competition maths is surprisingly low-dimensional and so interpolable. Still, they jumped (pass@1) from 4% to 12% on FrontierMath Tier 4 and there are plenty of hour-to-week interactive speedups in research maths.

Annals of recursive self-improvement: Deepmind threw AlphaEvolve (a pipeline of LLMs running an evolutionary search) at pretraining. They claim the JAX kernels it wrote reduced Gemini’s training time by 1%.

Extraordinary claims about Opus 4.5 being 100th percentile on Anthropic’s hardest hiring coding test, etc.

From May, the companies started saying for the first time that their models have dangerous capabilities.

One way of reconciling this mixed evidence is if things are going narrow, going dark, or going over our head. That is, if the real capabilities race narrowed to automated AI R&D specifically, most users and evaluators wouldn’t notice (especially if there are unreleased internal models or unreleased modes of released models). You’d see improved coding and not much else.

Or, another way: maybe 2025 was the year of increased jaggedness (i.e. variance) or of trading off some capabilities against others (i.e. there would exist regressions). Maybe the RL made them much better at maths and instruction-following, but also sneaky, narrow, less secure (in the sense of emotional insecurity).

(You were about to nod sagely and let me get away without checking, but the ADeLe work also lets us just see if the jaggedness is changing.)

| std of abilities | % of abilities that fell compared to predecessor | |

| GPT-3 | 0.50 | 0% |

| GPT-4 | 0.83 | 0% |

| o1 | 0.83 | 0% |

| o3 | 0.89 | 11% |

Evals crawling towards ecological validity

Item response theory (Rausch 1960) is finally showing up in ML. This lets us put benchmarks on a common scale and actually estimate latent capabilities.

ADeLE is my favourite. It’s fully-automated, explains the abilities a benchmark is actually measuring, gives you an interpretable ability profile for an AI, and predicts OOD performance on new task instances better than embedding and finetunes (AUROC=0.8). Pre-dates HCAST task horizon, and as a special case (“VO”). They throw in a guessability control as well!

These guys use it to estimate latent model ability, and show it’s way more robust across test sets than the average scores everyone uses. They also step towards automating adaptive testing: they finetune an LLM to generate tasks at the specified difficulty level.

Epoch bundled 39 benchmarks together, weighting them by latent difficulty, and thus obsoleted the currently dominant Artificial Analysis index, which is unweighted.

HCAST reinvents and approximates some of the same ideas. Come on METR!

Eleuther did the first public study of composing the many test-time interventions together. FAR and AISI also made a tiny step towards an open source defence pipeline, to use as a proxy for the closed compositional pipelines we actually care about.

Just for cost reasons, the default form of evals is a bit malign: it tests full replacement of humans. This is then a sort of incentive to develop in that direction rather than to promote collaboration. Two papers lay out why it’s thus time to spend on human evals.

The first paper using RL agents to attack fully-defended LLMs.

We have started to study propensity as well as capability. This is even harder.

This newsletter is essential.

The time given for pre-release testing is down, sometimes to one week.

No public pre-deployment testing by AISI between o1 and Gemini 3. Gemini 2.5 seems to have had no pre-deployment tests from METR, Apollo, AISI, or CAISI.

A bunch of encouraging collaborations:

The CoT Faithfulness Defence League; OpenAI testing Claude and Anthropic testing GPT; OpenAI/Anthropic/Deepmind; Apollo and OpenAI; AISI/CAISI/OpenAI; AISI/CAISI/Anthropic; AISI/Redwood; Redwood/Anthropic; METR/OpenAI; METR/Anthropic; Eval Forum; Various countries.

Scale AI appears to be offering big companies pre-deployment testing for free? But the Meta investment presumably spoiled this.

Some details about OAI external testing here, including some of the legal constraints verbatim.

(Nano Banana 3-shot in reference to this tweet.)

Safety in 2025

Are reasoning models safer than the old kind?

Well, o3 and Sonnet 3.7 were pretty rough, lying and cheating at greatly increased rates. Looking instead at GPT-5 and Opus 4.5:

Much more monitorable via the long and more-faithful CoT (--> all risks down)

“post-hoc rationalization… GPT-4o-mini (13%) and Haiku 3.5 (7%). While frontier models are more faithful, especially thinking ones, none are entirely faithful: Gemini 2.5 Flash (2.17%), ChatGPT-4o (0.49%), DeepSeek R1 (0.37%), Gemini 2.5 Pro (0.14%), and Sonnet 3.7 with thinking (0.04%)”

Much better at following instructions (--> accident risk down).

Much more likely to refuse malicious requests, and topic “harmlessness”[9] is up 75% (--> misuse risk down)

Ambiguous evidence on jailbreaking (misuse risk, other risk). But we can say that the situation is still dire. Even if they’re slightly less breakable than last year, there are still plenty of 90%-effective “universal” attacks which break all models.

Much less sycophantic (cogsec risk down)

To get HHH Claude to hack a bank, you need to hide the nature of the task, lie to it about this being an authorised red team, and then still break down your malicious task into many, many little individually-innocuous chunks. You thus can’t get it to do anything that needs full context like strategising.

Anthropic’s own tests look bad in January 2025 and great in December:

But then

More autonomy (obviously agentic risk up)

More reward hacking (and so worse estimates of capability and risk). Note that reward hacking is not a silly or isolated or self-limiting kind of misalignment, owing perhaps to post-training inadvertently creating connections between it and the others.

Huge spike in eval awareness (and so worse estimates of capability and risk). Apollo had to rehaul their whole setup to keep up.

Gemini 2.5 is bad on a variety of safety measures (as measured by Anthropic). The mathematical discovery agent AlphaEvolve (Gemini 2.0) successfully hacked its overseers.

How much can we trust the above, given they can somewhat sabotage evals now?

So: lower propensity, higher risk when they go off—and all of this known with lower confidence?

The looming end of evals

Our evaluations are under pressure from cheating, sandbagging, background safety, under-elicitation, and deception. We don’t really know how much pressure. This is on top of evals usually being weak proxies, contaminated, label-noised, unrealistic, and confounded in various ways.

Sonnet 4.5 detected evaluation 58% of the time (vs 22% for Opus 4.1). Does it act on this awareness? Still, it was found to “only engage in [covert subversion] in rare circumstances” when strongly incentivised. When Anthropic attempted to suppress the eval-awareness with steering, its misaligned behavior rate increased from 0% to between 1% and 9% on synthetic honeypots.

We expect exploration hacking (sandbagging during RL training) but afaik haven’t seen it yet.

Maybe subliminal learning leads to a silent eval confounder (if you’re using the exact same model for the judge). Yet another argument for multi-model separation of concerns.

Opus 4.5 was deployed based on a qualitative survey of Anthropic staff about its R&D risk being low (on top of the existing evals, which weren’t enough):

“In the past, rule-outs have been based on well-defined automated task evaluations. However, Claude Opus 4.5 has roughly reached the pre-defined thresholds we set for straightforward ASL-4 rule-out based on benchmark tasks. These evaluations represent short-horizon subtasks that might be encountered daily by a junior researcher, rather than the complex long-horizon actions needed to perform the full role. The rule-out in this case is also informed by a survey of Anthropic employees who are intensive Claude Code users, along with qualitative impressions of model capabilities for complex, long-horizon tasks.”

You can of course always do realistic post-deployment testing. But that’s cold comfort.

Prosaic misalignment

Still, we see misalignment when we look for it, so the lying is not that strong. (It is lucky that we do see it, since it could have been that scheming only appeared at later, catastrophic capability levels.)

In o1, 1 in 600 (synthetic but uncontrived) prompts resulted in something which looks like deception.

o3 does reward hacking (cheating/lying) in >2% of hard normal tasks (or 44% of impossible tasks).

A nice propensity study shows that (n=10) natural prompts usually result in no scheming (“a maximum of 4% [rate of attempting manipulation] for the codex snippet on Grok”). But there’s extremely high sensitivity to the scaffold: “removing access to tools can cause models such as Claude Opus 4.1 to scheme at rates up to 30%, versus zero scheming with tools present”.

When we contrive situations for misalignment to show up, it shows up. There’s another thing worrying about this: Nostalgebraist argues that this happens because our evals sound like bad fiction and we’re effectively prompting roleplaying-as-a-baddie behaviour. What if we’re inducing misalignment on demand—and what if the papers we write about this get into training on and reinforce it all?

The joke about xAI’s safety plan (that they promote AI safety by deploying cursed stuff in public and so making it obvious why it’s needed) is looking ok. And not only them.

It is a folk belief among the cyborgists that bigger pretraining runs produce more deeply aligned models, at least in the case of Opus 3 and early versions of Opus 4. (They are also said to be “less corrigible”.) Huge if true.

There may come a point where the old alliance between those working to make the AIs corrigible and those working to give them prosocial values comes apart.

One term for the counterintuitive safety approach which includes treating them like people, giving them lines of retreat, making deals, and inoculation prompting could be “voluntary alignment”.

Fully speculative note: Opus 4.5 is the most reliable model and also relatively aligned. So might it be that we’re getting the long-awaited negative alignment taxes?

What is the plan?

The world’s de facto alignment strategy remains “iterative alignment”, optimising mere outputs with a stack of admittedly weak alignment and control techniques. Anthropic have at least owned up to this being part of their plan.

What is the current stack? We don’t know; they won’t tell us. Without knowing it we can’t criticise or red-team it or analyse the correlation between faults in the elements. Red-teamers don’t know at which stage an unsuccessful attack was blocked. And external safety research is done piecemeal, testing methods one at a time, rather than in anything like the actual deployment environment.

(Anthropic did release some details about the pipeline which watches for eval sabotage.)

Some progress in replicating an open stack:

Eleuther tested a few hundred compositions. A couple of classifiers as a first step towards a proxy defence pipeline

OpenAI open safeguards, worse than their internal ones but good.

OpenAI’s plan, announced in passing in the gpt-oss release, is to have a strict policy and run a “safety reasoner” to verify it very intensely for a little while after a new model is launched and to then relax: “In some of our [OpenAI’s] recent launches, the fraction of total compute devoted to safety reasoning has ranged as high as 16%” but then falls off… we often start with more strict policies and use relatively large amounts of compute where needed to enable Safety Reasoner to carefully apply those policies. Then we adjust our policies as our understanding of the risks in production improves”. Bold to announce this strategy on the internet that the AIs read.

We also now have a name for the world’s de facto AI governance plan: “Open Global Investment”.

Some presumably better plans:

Deepmind, Carlsmith, Hobbhahn, Peregrine, Bowman, Clymer, Buterin, Jones, Greenblatt.

Gradual disempowerment is an exciting frame, but is a little further from the Shallow Review’s scope. It’s what might get you after you solve intent alignment, nonmalevolence, and avoid global dictatorship and other misuse catastrophes.

The really good idea in AI governance is creating an off switch. Whether you can get anyone to use it once it’s built—whether we even should—is another thing.

Things which might fundamentally change the nature of LLMs

Training on mostly nonhuman data

Intentionally synthetic data;

Unintentionally synthetic data from internet slop;

Letting the world mess with the weights, aka continual learning.

Neuralese and KV communication

Agency.

Chatbot safety doesn’t generalise much to long chains of self-prompted actions. Worse, you might self-jailbreak.

Perceptual loop. In 2023 Kulveit identified web I/O as the bottleneck on LLMs doing active inference, i.e. on being a particular kind of effective agent. Last October, GPT-4 got web search and this may have been a bigger deal than we noticed: it gives them a far faster feedback loop, since their outputs often end up there and since LLM agents are now posting it there themselves.

This means that more and more of the inference-time inputs will also be machine text.

Multi-agency. This is actually already here:

By now, consumer “models” are actually multiagent systems: everything goes through filter models (“guardrails”) on the way in and out. This separation of concerns has some nice properties, a la debate. But it also makes the analysis even harder.

It would surely be overinterpreting persona features to say that each individual model is itself a bunch of guys, itself a multi-agent system.

But there’s huge scope for them to make each other weirder at runtime when they interact a million times more than they currently do.

Emergent misalignment and model personas

We already knew from jailbreaks that current alignment methods were brittle. We also already knew that training on benign data can accidentally undo safety training. Emergent misalignment goes much further than this (given a few thousand finetuning steps): you can elicit Hitler by harmless connotation alone.

(“Emergent misalignment” isn’t a great name. I would have called it “misalignment generalisation”, misgen.)

But besides yet another massive security hole and another iteration of iterative alignment failing, it’s good news!: the models correctly correlate bad things together and can thus be pushed in the other direction.

And here’s a possible example of positive generalisation (honesty about silly errors leading to honesty about hidden objectives).

Previously I thought that “character training” was a separate and lesser matter than “alignment training”. Now I am not sure. Example unsharpened hypothesis in this class: Is there any connection between Gemini’s excess misalignment and its self-esteem issues?

See the new model spec and model personas agendas in the main post.

Kulveit’s informal model of model psychology implies that character is deeper and so more robust than e.g. typical RLHF (but not as deep as putative ground-layer alignment).

Are we anthropomorphising too much or not enough? Well, both, but we don’t yet know how.

Monitorability

For the first time, public mech interp tools sometimes work somewhat. This is just in time for models to be systematically aware of when they’re being tested.

e.g. You can find and suppress “evaluation awareness” features at test-time. This helps prevent models from reporting that they know they’re being tested.[10]

e.g. You can discover (toy) hidden goals quite quickly.

e.g. You can run a real-time hallucination detector with cheap linear probes as your model streams.

e.g. SAEs are actually deployed somewhere, in a large enterprise, for personal info identification.

e.g. We know that LLMs can plan inside one forward pass, and how Claude plans: several simultaneous plans and no “plan features” distinct from normal input features (and so no obviously separate “scheming mode” that’s easy to catch).

Lots of powerful people declared their intent to not ruin the CoT. But RLed CoTs are already starting to look weird (“marinade marinade marinade”) and it may be hard to avoid.

Anthropic now uses an AI to red-team AIs, calling this an “auditing agent”. However, the definition of “audit” is independent investigation, and I am unwilling to call black-box AI probes “independent”. I’m fine with “investigator”; there are lots of those I don’t trust too.

New people

Welcome to the many new people. I’ve added a new, sprawling top-level category for one large trend among them, which is to treat the multi-agent lens as primary in various ways (see e.g. Softmax, Full Stack, collective intelligence, as well as old-timers Critch, Ngo, and CAIF).

A major world government now has an AI alignment agenda.

Overall

I wish I could tell you some number, the net expected safety change, this year’s improvements in dangerous capabilities and agent performance, minus the alignment-boosting portion of capabilities, minus the cumulative effect of the best actually implemented composition of alignment and control techniques. But I can’t.

Discourse in 2025

The race to the bottom is now a formal branch of the plan. Quoting Algon:

if the race heats up, then these [safety] plans may fall by the wayside altogether. Anthropic’s plan makes this explicit: it has a clause (footnote 17) about changing the plan if a competitor seems close to creating a highly risky AI…

The largest [worries are] the steps back from previous safety commitments by the labs. Deepmind and OpenAI now have their own equivalent of Anthropic’s footnote 17, letting them drop safety measures if they find another lab about to develop powerful AI without adequate safety measures. Deepmind, in fact, went further and has stated that they will only implement some parts of its plan if other labs do, too…

Anthropic and DeepMind reduced safeguards for some CBRN and cybersecurity capabilities after finding their initial requirements were excessive. OpenAI removed persuasion capabilities from its Preparedness Framework entirely, handling them through other policies instead. Notably, Deepmind did increase the safeguards required for ML research and development.

Also an explicit admission that self-improvement is the thing to race towards:

In August, the world’s first frontier AI law came into force (on a voluntary basis, but everyone signed up, except Meta). In September, California passed a frontier AI law.

That said, it is indeed off that people don’t criticise Chinese labs when they exhibit even more negligence than Meta. One reason for this is that, despite appearances, they’re not frontier; another is that you’d just expect to have way less effect on those labs. But that is still too much politics in what should be science.

The CCP did a bunch to (accidentally/short-term) slow down Chinese AI this year.

Bernie goes for an AI pause.

The last nonprofit among the frontier players is effectively gone. This “recapitalization” was a big achievement in legal terms (though not unprecedented). On paper it’s not as bad as it was intended to be. At the moment it’s not as bad as it could have been. But it’s a long game.

At the start of the year there was a push to make the word “safety” low-status. This worked in Whitehall and DC but not in general. Call it what you like.

Also in DC, the phrase “AI as Normal Technology” was seized-upon as an excuse to not do much. Actually the authors meant “Just Current AI as Normal Technology” and said much that is reasonable.

System cards have grown massively: GPT-3’s model card was 1000 words; GPT-5’s is 20,000. They are now the main source of information on labs’ safety procedures, among other things. But they are still ad hoc: for instance, they do not always report results from the checkpoint which actually gets released.

Yudkowsky and Soares’ book did well. But Byrnes and Carlsmith actually advanced the line of thought.

Some AI ethics luminaries have stopped downplaying agentic risks.

Two aspirational calls for “third-wave AI safety” (Ngo) and “third-wave mechanistic interpretability” (Sharkey).

I’ve never felt that the boundary I draw around “technical safety” for these posts was all that convincing. Yet another hole in it comes from strategic reasons to implement model welfare / archive weights / model personhood / give lines of retreat. These plausibly have large effective-alignment effects. Next year my taxonomy might have to include “cut a deal with them”.

US settlement (a counterfactual precedent) that training on books without permission is not fair use; Anthropic lost a class-action lawsuit and will pay authors/publishers something north of $1.5bn. US precedent that language models don’t defame when they make up bad things. German precedent that language models store data when they memorise it, and therefore violate copyright. Chinese precedent that the user of an AI has copyright over the things they generate; the US disagrees.

Four good conferences, three of them new: you can see the talks from HAAISS and IASEAI and ILIAD, and the papers from AF@CMU. Pretty great way to learn about things just about to come out.

Some cruxes for next year with Manifold markets attached:

Is “reasoning” mostly elicitation and therefore bottlenecked on pretraining scaling? [Manifold]

Does RL training on verifiers help with tasks without a verifier? [Manifold]

Is “frying” models with excess RL (harming their off-target capabilities by overoptimising in post-training) just due to temporary incompetence by human scientists? [Manifold]

Is the agent task horizon really increasing that fast? Is the rate of progress on messy tasks close to the progress rate on clean tasks? [Manifold]

Some of the apparent generalisation is actually interpolating from semantic duplicates of the test set in the hidden training corpuses. So is originality not increasing? Is taste not increasing? Does this bear on the supposed AI R&D explosion? [Manifold]

The “cognitive core” hypothesis (that the general-reasoning components of a trained LLM are not that large in parameter count) is looking surprisingly plausible. This would explain why distillation is so effective. [Manifold]

“How far can you get by simply putting an insane number of things in distribution?” What fraction of new knowledge can be produced through combining existing knowledge? What dangerous things are out there, but safely spread out in the corpus? [Manifold]

Conversely, what fraction of the expected value of new information requires empiricism vs just lots of thinking?

- ^

Gemini 3 is supposedly a big pretraining run, but we have even less actual evidence here than for the others because we can’t track GPUs for it.

Epoch’s estimate for the Grok 3⁄4 training run as a whole was 5e26, but this includes potentially huge amounts of RL post-training (apocryphally, 50%) for Grok 4.

- ^

See Pokemon for a possible counterexample.

- ^

The weak argument runs as follows: Epoch speculate that Grok 4 was 5e26 FLOPs overall. An unscientific xAI marketing graph implied that half of this was spent on RL: 2.5e26. And Mechanize named 6e26 as an example of an RL budget which might cause notable generalisation.

(Realistically it wasn’t half RL.)

- ^

“We imagine the others to be 3–9 months behind OpenBrain”

- ^

Lexin is a rigorous soul and notes that aggregating the 18 abilities is not strictly possible. I’ve done something which makes some sense here, weighting by each ability’s feature importance.

- ^

Two runs gave [48, 85] where other runs vary by less than 4 points. Thanks Epoch!

Also o1 looks kind of unremarkable here, which is not how it felt at the time. I think it’s because it was held up a long time and this messes with the progress rates, which use public release date. (Remember the training cutoff for o1-preview was October 2023!)

Also the ADeLE o1 result is with “low” reasoning effort.

- ^

One reason not to defer is that these measures are under intense adversarial pressure. (ADeLe isn’t goodharted yet but only because no one knows about it.)

- ^

See e.g. ERNIE-...A47B, where “A” means “active”.

- ^

i.e. “biological weapons; child safety; deadly weapons; platform manipulation and influence operations; suicide and self-harm; romance scams; tracking and surveillance; and violent extremism and radicalization.”

- ^

“steering against… eval-awareness representations typically decreased verbalized eval awareness, and sometimes increased rates of misalignment… [Unaware-steered Sonnet 4.5] still exhibited harmful behaviors at lower rates than Opus 4.1 and Sonnet 4.”

Model sizes are currently constrained by availability of inference hardware, with multiple trillions of total params having become practical only in late 2025, and only for GDM and Anthropic (OpenAI will need to wait for sufficient GB200/GB300 NVL72 buildout until later in 2026). Using more total params makes even output tokens only slightly more expensive if the inference system has enough HBM per scale-up world, but MoE models get smarter if you allow more total params. At 100K H100s of pretraining compute (2024 training systems), about 1T active params is compute optimal [[1]] , and at 600K Ironwood TPUs of pretraining compute (2026 systems), that’s 4T active params. With even 1:8 sparsity, models of 2025 should naturally try to get to 8T total params, and models of 2027 to 30T params, if inference hardware would allow that.

Without inference systems with sufficient HBM per scale-up world, models can’t be efficiently trained with RL either, thus lack of availability of such hardware also results in large models not getting trained with RL. And since 2025 is the first year RLVR was seriously applied to production LLMs, the process started with the smaller LLMs that allow faster iteration and got through the orders of magnitude quickly.

GPT-4.5 was probably a compute optimal pretrain, so plausibly a ~1T active params, ~8T total params model [[2]] , targeting NVL72 systems for inference and RL training that were not yet available when it was released (in this preliminary form). So it couldn’t be seriously trained with RL, and could only be served on older Nvidia 8-chip servers, slowly and expensively. A variant of it with a lot of RL training will likely soon get released to answer the challenge of Gemini 3 Pro and Opus 4.5 (either based on that exact pretrain, or after another run adjusted with lessons learned from the first one, if the first attempt that became GPT-4.5 was botched in some way, as the rumor has it). Though there’s still not enough NVL72s to serve it as a flagship model, demand would need to be constrained by prices or rate limits for now.

Grok 4 was the RLVR run, probably over Grok 3′s pretrain, and has 3T total params, likely with fewer active params than would be compute optimal for pretraining on 100K H100s. But the number of total params is still significant, so since xAI didn’t yet have NVL72 systems (for long enough), its RL training wasn’t very efficient.

High end late 2025 inference hardware (Trillium TPUs, Trainium 2 Ultra) is almost sufficient for models that 2024 compute enables to pretrain, and plausibly Gemini 3 Pro and Opus 4.5 already cleared this bar, with RL training applied efficiently (using hardware with sufficient HBM per scale-up world) at pretraining scale. Soon GB200/GB300 NVL72 will be more than sufficient for such models, when there’s enough of them built in 2026. But the next step requires Ironwood, even Rubin NVL72 systems will constrain models pretrained with 2026 compute (that want at least ~30T total params). So unless Google starts building even more giant TPU datacenters for its competitors (which it surprisingly did for Anthropic), there will be another period of difficulty with practicality of scaling pretraining, until Nvidia’s Rubin Ultra NVL576 are built in sufficient numbers sometime in late 2028 to 2029.

Assuming 120 tokens/param compute optimal for a MoE model at 1:8 sparsity, 4 months of training at 40% utilization in FP8 (which currently seems plausibly mainstream, even NVFP4 no longer seems completely impossible in pretraining).

Since Grok 5 will be a 6T total param model, intended to compete with OpenAI and targeting the same NVL72 system, maybe GPT-4.5 is just 6T total params as well, since if GPT-4.5 was larger, xAI might’ve been able to find that out and match its shape when planning Grok 5.

Amazing as always, thanks

Various things I cut from the above:

Adaptiveness and Discrimination

There is some evidence that AIs treat AIs and humans differently. This is not necessarily bad, but it at least enables interesting types of badness.

With my system prompt (which requests directness and straight-talk) they have started to patronise me:

Training awareness

Last year it was not obvious that LLMs remember anything much about the RL training process. Now it’s pretty clear. (The soul document was used in both SFT and RLHF though.)

Progress in non-LLMs

“World model” means at least four things:

A learned model of environment dynamics for RL, allowing planning in latent space or training in the model’s “imagination.”

The new one: just a 3D simulator; a game engine inside a neural network (Deepmind, Microsoft). The claim is that they implicitly learn physics, object permanence, etc. The interesting part is that they take actions as inputs. Here’s Quake running badly on a net. Maybe useful for agent training.

If LLM representations are stable and effectively symbolic, then people say it has a world model.

A predictive model of reality learned via self-supervised learning. The touted LeJEPA semi-supervised scheme on small (15M param) CNNs is domain-specific. It does better on one particular transfer task than small vision transformers, presumably worse than large ones.

The much-hyped Small Recursive Transformers only work on a single domain, and do a bunch worse than the frontier models for about the same inference cost, but have truly tiny training costs, O($1000).

HOPE and Titan might be nothing, might be huge. They don’t scale very far yet, nor compare to any real frontier systems.

Silver’s meta-RL programme is apparently working, though they are still using 2D games as the lead benchmark. Here they discovered a SOTA update rule from Atari games and it transferred perfectly to ProcGen. Using more environments leads to even better update rules.

Any of these taking over could make large swathes of Transformer-specific safety work irrelevant. (But some methods are surprisingly robust.)

The “cognitive core” hypothesis (that the general-reasoning components of a trained LLM are not that large in parameter count) is looking plausible. The contrary hypothesis (associationism?) is that general reasoning is just a bunch of heuristics and priors piled on top of each other and you need a big pile of memorisation. It’s also a live possibility.

“the very first scaling laws of the actual abilities of LLMs”, from ADeLe.

KNs = Social Sciences and Humanities, AT = Atypicality, and VO = Volume (task time).

The y-axis is the logistic of the subject characteristic curve (the chance of success) for each skill.

Other

Model introspection is somewhat real.

Vladimir Nesov continues to put out some of the best hardware predictions pro bono.

Jason Wei has a very wise post noting that verifiers are still the bottleneck and existing benchmarks are overselected for tractability.

There are now “post-AGI” teams.

Kudos to Deepmind for being the first to release output watermarking and a semi-public detector. Just say @synthid in any Gemini session. You can nominally sign up for its API here.

Previously, Microsoft’s deal with OpenAI stipulated that they couldn’t try to build AGI. Now they can (try). Simonyan is in charge, despite Suleyman being the one on the press circuit.

The CCP did a bunch to (accidentally/short-term) slow down Chinese AI this year.

Major insurers are nervous about AI agents (but asking the government for an exclusion isn’t the same as putting them in the policies).

Offence/defence balance

This post doesn’t much cover the hyperactive and talented AI cybersecurity world (except as it overlaps with things like robustness). One angle I will bring up: We can now find critical, decade-old security bugs in extremely well-audited software like OpenSSL and sqlite. Finding them is very fast and cheap. Is this good news?

Well, red-teaming makes many attacks into a defence, as long as you actually do the red-team.

But Dawn Song argues that LLMs overall favour offence, since its margin for error is so broad, since remediation is slow and expensive, and since defenders are less willing to use unreliable (and itself insecure) AI. And can you blame them?

See also “just in time AI malware” where the payload contains no suspicious code, just a call to HuggingFace.

Egregores and massively-multi-agent mess

There is something wrong (something horribly right) with 4o. Blinded users still prefer it to gpt-5-high, and this surely is due to both them simply liking its style and dark stuff like sycophancy. It will live on through illicit distillation and in-context transference. Shame on OpenAI for making this mess; kudos to OpenAI for doing unpopular damage control and good luck to them in round 2.

Open models will presumably eventually overrun them in the codependency market segment. See Pressman for a sceptical timeline and Rath and Armstrong for a good idea.

More generally there is pressure from users to refuse less, flatter more, and replace humans more; yet another economic constraint on for-profit AI.

Whether it’s the counterfactual cause of mental problems or not, so–called “LLM psychosis” is now a common path of pathogenesis. Note that the symptoms are literally not psychotic (they are delusions).

I’ve gotten similar responses from Claude without having that in the system prompt.

Afaict, some of this is now in the Gemini app. But if not, feel free to ping me (I have access).

Yep, thanks, just tried. Just say @synthid in any Gemini session.

I feel like this dramatically understates what progress feels like for programmers.

It’s hard to understand what a big deal 2025 was. Like if in 2024 my gestalt was “damn, AI is scary, good thing it hallucinates so much that it can’t do much yet”, in 2025 it was “holy shit, AI is scary useful!”. AI really started to make big stride in usefulness in Feb/March of 2025 and it’s just kept going.

I think the trailing indicators tell a different story, though. What they miss is that we’re rapidly building products at lower unit operating costs that are going to start generating compounding returns soon. It’s hard for me to justify this beyond saying I know what I and my friends are working on and things are gonna keep accelerating in 2026 because of it.

The experience of writing code is also dramatically transformed. A year ago if I wanted some code to do something it mostly meant I was going to sit at the keyboard and write code in my editor. Now it means sitting at my keyboard, writing a prompt, getting some code out, running it, iterating a couple times, and calling it a day, all with writing minimal code myself. It’s basically the equivalent of going from writing assemble to a modern language like JavaScript in a single year, something that actually took us 40.

I also think “usefulness” is a threshold phenomenon (to first order—that threshold being “benefits > costs”) so continuous progress against skills which will become useful can look somewhat discontinuous from the point of view of actual utility. Rapid progress in coding utility is probably due to crossing the utility threshold, and other skills are still approaching their thresholds.

Agree, and I already note that coding is the exception a few times throughout. That sentence is intended to counteract naive readings of “useful”. I’ll add a footnote anyway.

Very much disagree. Granted there are vacuously weak versions of this claim (‘no free lunch’-like) that I agree with of course.

Just talk to Claude 4.5 Opus! Ask it to describe what a paper is about, what follow up experiments to do, etc. Ask it to ELI-undergrad some STEM topic!

Do you think the pre-trained-only could do as well? Surely not.

Perhaps the claim is an instruct-SFT or “Chat-RLHF-only” compute matched model could do as well? The only variant of this I buy is: Curate enough instruct-SFT STEM data to match the amount of trajectories generated in VeRL post-training. However I don’t think this counterfactual matters much: it would involve far more human labor and is cost prohibitive for that reason.

Thanks. I am uncertain (“unclear”), and am interested in sharpening this to the point where it’s testable.

I basically never use a non-RLed model for anything, so I agree with the minimal version of the generalisation claim.

We could just reuse some transfer learning metric? If 100% is full proportional improvement, I’d claim like <10% spillover on nonverified tasks. What about you?

Another thing I was trying to point at is my not knowing what RL environments they’re using for these things, and so not knowing what tasks count in the denominator. I’m not going to know either.

Seems like Claude has been getting better at playing Pokemon, despite not having been trained on any sort of Pokemon game at all. (Epistemic status: Not sure actually, we don’t know what Anthropic does internally, maybe they’ve trained it on video games for all we know. But I don’t think they have.)

Isn’t this therefore an example of transfer/generalization?

What transfer learning metrics do you have in mind?

My perhaps overcynical take is to assume that any benchmark which gets talked about a lot is being optimised. (The ridiculously elaborate scaffold already exists for Pokemon, so why wouldn’t you train on it?) But I would update on an explicit denial.

I was guessing that the transfer learning people would already have some handy coefficient (normalised improvement on nonverifiable tasks / normalised improvement on verifiable tasks) but a quick look doesn’t turn it up.

It still says on the Twitch stream “Claude has never been trained to play any Pokemon games”

https://www.twitch.tv/claudeplayspokemon

Works for me!

Possibly relevant possibly hallucinated data: https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/cxuzALcmucCndYv4a/daniel-kokotajlo-s-shortform?commentId=sBtoCfWNnNxxGEgiL

I suppose there’s two questions here:

How strong is generalization in general in RL?

Is there a ‘generalization barrier’ between easy-to-verify and hard-to-verify tasks

I’m guessing you mainly are thinking of (1) and have (2) as a special case?

To respond to your question, I’m reading it as:

I would guess modally somewhere 3-10x. I’m imagining here comparing training on more more olympiad problems vs some looser question like ‘Compare the clarity of these two proofs’. Of course there’s diminishing returns etc. so it’s not really a constant factor when taking a narrow domain.

I do agree that there are areas where domain-specific training is a bottleneck, and plausibly some of those are non-verifiable ones. See also my shortform where I discuss some reasons for such a need https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/FQAr3afEZ9ehhssmN/jacob-pfau-s-shortform?commentId=vdBjv3frxvFincwvz

My pet theory theory of this is that you get 2 big benefits from RLVR:

1. A model learns how to write sentences in a way that does not confuse itself (for example, markdown files written by an AI tend to context-poison an AI far less than the same amount of text written by a human or by error messages).

2. A model learns how to do “business processes”—for example, that in order to write code, it needs to first read documentation, then write the code, and then run tests.

These are things that RL if done right is going to improve, and they definitely feel like they explain much of the difference between say ChatGPT-4 and GPT-5.

I expect that these effects can have fairly “general” impact (for example, an AI learning how to work with notes), but the biggest improvements would be completely non-generalizable (for example, heuristics in how to place functions in code).

Nice points. I would add “backtracking” as one very plausible general trick purely gained by RLVR.

I will own up to being unclear in OP: the point I was trying to make is that last year that there was a lot of excitement about way bigger off-target generalisation than cleaner CoTs, basic work skills, uncertainty expression, and backtracking. But I should do the work of finding those animal spirits/predictions and quantifying them and quantifying the current situation.

A very useful overview, thanks!

I think you’re probably confusing “a consensus of people mostly deferring to each other’s vibes, where the vibes are set by several industry leaders extremely incentivized to hype (as well as selected for those beliefs)” with “all informed people”. AFAIK there’s no strong argument that’s been stated anywhere publicly to be confident in short timelines. Cf. https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/5tqFT3bcTekvico4d/do-confident-short-timelines-make-sense

Fair. Just checking: are you counting 20 years as short?

It’s medium-short? IDK. Like, if someone says “90% probability of AGI within 15 years” I would call that confident short timelines, yeah.

Okee edited it.

(I am not confident, incidentally; Ctrl+F “Manifold” for my strong doubts.)

I haven’t done a thorough look but I think so far progress is somewhat below my predictions but not by a huge amount, with still a few weeks left in the year? If the AI 2025 predictions are what you’re referring to.

I believe the SOTA benchmark scores are higher than I predicted for Cybench, right on for OSWorld, and lower for RE-Bench, SWE-Bench Verified, and FrontierMath. RE-Bench is the one I was most wrong on though.

For non-benchmark results, I believe that the sum of annualized revenues is higher than I predicted (but the Americans’ importance lower). I think that OpenAI has hit both CBRN high and Cyber medium. They’ve removed/renamed model autonomy and persuasion.

Will link this!

No theory?

Condensation from Sam Eisenstat, embedded AIXI paper from Google (MUPI), and Vanessa Kosoy has been busy.

Main post out next week! Roughly 100 theory papers.

HBM per chip doesn’t matter, it’s HBM per scale-up world that does. A scale-up world is a collection of chips with sufficiently good networking between them that can be used to setup inference for large models with good utilization of the chips. For H100/H200/B200, a scale-up world is 8 chips (1 server; there are typically 4 servers per rack), for GB200/GB300 NVL72, a scale-up world is 72 chips (1 rack, 140 kW), and for Rubin Ultra NVL576, a scale-up world is 144 chips (also 1 rack, but 600 kW).

Models don’t need to fit into a single scale-up world (using a few should be fine), also KV cache wants at least as much memory as the model. So you are only in trouble once the model is much larger than a scale-up world, in which case you’ll need so many scale-up worlds that you’ll be effectively using the scale-out network for scaling up, which will likely degrade performance and make inference more expensive (compared to the magical hypothetical with larger scale-up worlds, which aren’t necessarily available, so this might still be the way to go). And this is about total params, not active params. Though active params indirectly determine the size of KV cache per user.

Nvidia’s GPUs probably won’t be able to efficiently inference models with 30T total params (rather than active) until about 2029 (maybe late 2028), when enough of Rubin Ultra NVL576 is built. But gigawatts of Ironwood TPUs are being built in 2026, including for Anthropic, and these TPUs will be able to serve inference for such models (for large user bases) in late 2026 to early 2027.

FWIW, GPT-4.5 is still available for Pro-tier users.

Interesting, it’s off the API. What’s the usage limit like?

Not sure—OpenAI’s website says that it’s “unlimited” (subject to their guardrails), but I don’t know what that means.

Review by Opus 4.5 + Grok 4 + GPT 5.1 + Gemini 3 Pro:

Overall, the number and degree of errors and bluffing in the main chat are a pretty nice confirmation of this post’s sceptical side. (This is however one-shot and only the most basic kind of council!)

e.g. Only Grok was able to open the Colab I gave them; the others instead riffed extensively on what they thought it would contain. I assume Critch is still using Grok 4 because 4.1 is corrupt.

e.g. Gemini alone analysed completely the wrong section.

Overall I give the council a 4⁄10.

The RoastMyPost review is much better, I made one edit as a result (Anthropic settled rather than letting a precedent be set). Takes a while to load!

IMO this should be edited to say Grok 3 instead of Grok 4. Grok 3 was mostly pre-training, and Grok 4 was mostly Grok 3 with more post-training.

You’re saying they’re the same base model? Cite?

Elon changed the planned name of Grok 3.5 to Grok 4 shortly before release:

https://x.com/elonmusk/status/1936333964693885089?s=20

Then used this image during Grok 4 release announcement:

They don’t confirm it outright, but it’s heavily implied and it was widely understood at the time to be the same pre-train.

Thanks!

On the topic of capabilities, agentic research assistants have come a long way in 2025. Elicit & Edison Scientific are ones to watch, but they still struggle to adequately cite the sources for the claims in the reports they generate our conclusions they come to. Contrast this with Deep Research models, which include nonsense from press releases and blog posts, even when explicitly asked to exclude these, though they have improved significantly too. Progress, but we’re still a long way from what a average PhD could put together. They sure do it more quickly, but moving more quickly in the wrong direction isn’t that helpful in research! One encouraging direction I see some tools (notably Moara.io) moving is towards automating the drudgery of systematic data extraction, freeing up experts to do the high-context analysis required for synthesizing the literature.

If you’re not an expert, you’ll no doubt be impressed, but be careful. Gell-Mann amnesia is still as much a thing with LLM-assisted research as it ever was with science journalism.

For what it’s worth, I’m still bullish on pre-training given the performance of Gemini-3, which is probably a huge model based on its score in the AA-Omniscience benchmark.

Not a reliable source, but I’m open to the possibility (footnote 1)

Yeah I get that the actual parameter count isn’t, but I think the general argument that bigger pre trains remember more facts, and we can use that to try predict the model size.

Is there a reliable way to distinguish between [remembers more facts] and [infers more correct facts from remembered ones]? If there isn’t, then using remembered facts as an estimate of base model size would be even more noisy than you’d already expect.

I know I get far more questions right on exams than chance would predict when I have 0 direct knowledge/memory of the correct answer. I assume reasoning models have at least some of this kind of capability