An Opinionated Guide to Using Anki Correctly

I can’t count how many times I’ve heard variations on “I used Anki too for a while, but I got out of the habit.” No one ever sticks with Anki. In my opinion, this is because no one knows how to use it correctly. In this guide, I will lay out my method of circumventing the canonical Anki death spiral, plus much advice for avoiding memorization mistakes, increasing retention, and more, based on my five years’ experience using Anki.

This guide comes in four parts, with the most important stuff in Parts I & II and more advanced tips in Parts III & IV. If you only have limited time/interest, only read Part I; it’s most of the value of this guide!

Roadmap to the Guide

This guide’s structure is inspired by how someone new to Anki might want to read it:

Part I contains day 1 advice for using Anki in a way that prevents the Anki death spiral. (But it is not a general intro to Anki; I leave that to other resources.)

Part II aims to save you from common mistakes, especially ones that waste effort without increasing your recall, for day 3 of using Anki.

Part III dives into more detailed card design issues, including for difficult and interrelated “information thickets”, for week 3 of using Anki.

Part IV contains even more & obscure pro tips for Anki, for week 5 of using Anki.

But Anki users of all experience levels have found this guide useful by skimming & skipping between the parts that were new/interesting to them!

My Most Important Advice in Four Bullets

20 cards a day — Having too many cards and staggering review buildups is the main reason why no one ever sticks with Anki. Setting your review count to 20 daily (in deck settings) is the single most important thing you can do to stick with Anki long-term.

Atomic cards — Studying long cards is gruelling. Studying cards with 1-5 words on the back is fun. Make every card as short as humanly possible (even 1 word!) by breaking things up into many cards.

No to-be-learned information in the prompt — You’re only memorizing the back of cards. Don’t put any to-be-learned information on the front. If recalling the back of a card is not useful without knowing crucial info given in the prompt, the card is not useful.

Bland prompts — Make prompts as absolutely non-descript and standardized as possible. Otherwise, you will learn a dumb pattern like prompt with fancy words → recall X, or funny typesetting → recall X, and not be able to recall X outside Anki at all.

I. Anki Day 1: Or, No One Ever Sticks With Anki

I cannot emphasize enough how often I’ve met people who want to use Anki in principle, but don’t seem to be able to create a long-term habit. (This was also me for most of my five years on-and-off using it.) No one ever sticks with Anki. I believe I know the two reasons for this:

Too many cards

Too long cards

Solving these two problems is probably 90% of the value of this guide. Let’s get into it.

Too many cards

People usually enthusiastically start by revising like 50+ new cards in a day. Then the enthusiasm wears off, and you skip a day. Next day, there are like 200 revisions due. Then you are discouraged, skip that day as well, along with the next seven, until you have about a million cards due and see no way of ever getting through them. This is the canonical Anki death spiral.

Instead, set a daily limit on card reviews of 10 or 20. This is perhaps my most important piece of advice. Really, do it. Yes, you will learn fewer cards. But the alternative (in my experience) is not using Anki long-term at all. If you set your daily review limit to 20, even if you skip a day (or ten), Anki will only show you 20 cards due after. This prevents procrastination spirals. You are always capable of doing 20 reviews after all, no matter the day.

If you truly feel like doing more on a given day, you can always increase your limit for that day by another 20 (long-tap the deck > Custom Study > Modify Today’s Review Card Limit). You can do this as often as you like, which, in any case, is more fun than doing one monster heap of reviews. (But doing it too much on one day is probably not sensible, as you won’t be able to review all those new cards within your normal daily limit going forward.)

You can set your daily review limit by long-tapping the deck > Deck options > “Daily Limits” at the top. If you set the daily review limit to 20, you should set the daily limit of new cards to 2, since otherwise your reviews won’t keep pace with your adding new cards. If you set the review limit to 10, you should set the new card limit to 1, etc.[1] This assumes that you have one deck; otherwise, the limits would have to be even lower per deck. (As an aside, I think it’s totally fine to have basically one deck for everything. I have such a deck, containing history facts alongside math alongside friends’ birthdays, and this is not a problem. The only separate decks I’ve ever needed were for language learning and university courses.)

I really think a limit of 20 is plenty to start with. I’m a pretty disciplined person, and I struggle with anything over 20 on some days. Also, if 20 goes well for a month or so, and you really want to do more, you can always increase the limit then.

And that’s it. This solves half the problem of the canonical Anki death spiral! Now for the other half.

Too long cards

When I started using Anki, I would often take an entire topic/text of interest, convert it into bullet points, and dump them all onto one Anki card. The card would then expect me to recite the whole thing in one big laundry list of information. This is super cognitively demanding and unfun. On the other end of the spectrum, now, I often have cards that have literally one word on the back, e.g., “pronunciation τ” → “tau”. And guess what? Revising these cards is actively fun! I would happily do fifty of these in my free time, whereas nothing could get me to do one of the “laundry list” variety again.

The lesson here, if you want to build a long-term Anki habit, is simply to make cards short. A typical card should have no more than 9 words. (If you write in sentences, and not abbreviated bullets like me, maybe a few more). This requires breaking information down into multiple cards. As a rule, if it is possible to break down a card into two shorter cards, you should do so. For example, consider this card:

In fact, there is no reason to learn the pronunciation of τ and what it means in one card. And shorter cards are more fun, therefore:

The ideal is to have “atomic” cards, i.e., cards that are as small as possible and whose meaning could not be preserved when splitting further. Of course, this is practically inconvenient because it takes too much time, so it is only an ideal.

Enforcing extreme brevity has the additional benefit of uncovering when I don’t actually understand something very precisely. If I don’t understand it, I can’t break it down. Ankifying routinely forces me to reread the source or to google, which is a pretty valuable impulse in and of itself.

How to keep cards short — Handles

Alas, breaking down cards is often harder than in the example above. E.g., you may start with a long text of interrelated information and somehow want to “ankify” this to remember it. For such rich information “thickets”, I must say it takes some extra time to break it down into sensible Anki cards, but it is 100% possible! The key is not to try to squeeze everything into one card but to allow Anki cards to refer to one another for more information. This way, you can split up information without making it meaningless taken out of context.

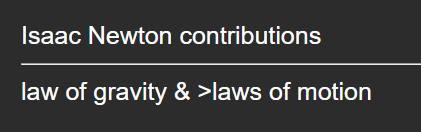

E.g., say you want to remember what Sir Isaac Newton’s key scientific contributions were. You could allow your card to refer to another card as follows:

It would be a mistake to make the first card longer by detailing what the laws of motion are. Instead, the little ‘>’ indicates a reference to another card, which has more information on the laws of motion. This way, the present card can remain short. You would now not have to recall all the laws of motion when revising it, but the reference ensures that you could. (> is just a convention I like to use; you could write this any way you like.)

I call these little ‘>’ referring to other cards ‘handles’ and I use them all the time to keep cards short. If something doesn’t have to be detailed on your card, but has to be remembered as related, you should probably use a handle. Handles don’t even necessarily have to contain any information in and of themselves, as “laws of motion” does; they can also purely be for splitting things up. E.g., if your card on Isaac Newton is getting too long, you could split out any logical subset of it and give it some handle name (that needn’t contain information in and of itself). For example:

It’s also totally okay to make cards that contain only handles. These are often necessary for splitting topics into manageable chunks, and they ensure that you remember how these chunks fit together.

How to keep cards short — Levels

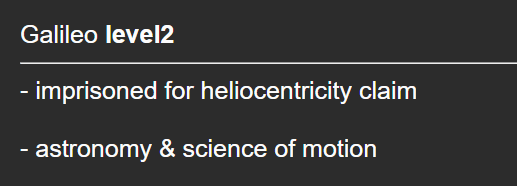

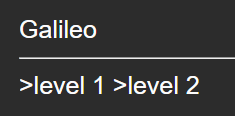

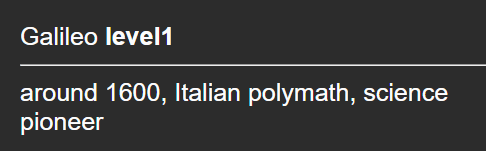

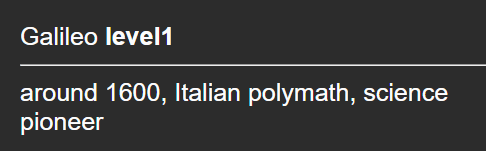

Another trick I like for keeping cards short is to have multiple cards adding increasing levels of detail on the same concept. Let’s say you want to remember stuff about Galileo Galilei. Instead of squeezing everything into one card, you could have a “level 1” card and a “level 2″ card like this:

Level 2 adds further detail while still being short of itself. To get even closer to the “atomic card” ideal, one could also separate out the date from the level 1 card and make a “Galileo date → around 1600″ card (and various other such improvements). But I think these two cards are pretty good.

In my experience, it pays off to make an additional third card simply to ensure that you recall you have two cards on Galileo.

(Note that these Galileo cards, just like any other cards in this post, are only examples of what someone might want to memorize. If it’s not important to you when Galileo lived, then by no means ankify it. I think you should have a pretty high bar for what’s important enough to ankify.)

At the absolute maximum, a card should have 3 logical bullets with a total of 18 words (in my opinion). Such a length is never necessary, but sometimes undeniably convenient.

In 6 bullets

Set a daily review limit of 10 or 20 cards.

If you feel like doing more on a given day, increase your limit for that day by another 10⁄20 as often as you like.

Max 9 words for most cards. At absolute max, 3 logical bullets/18 words.

If it’s possible to break a card up further, do it.

Use >handles to split out details / logical subsets.

Use level 1/2/3 cards to learn increasing detail on the same concept.

End of the most important part of the guide

And that’s it! This is my simple recipe for sticking with Anki when 90%[2] of people don’t: Keep few cards and keep them short. Try it and it should become apparent very quickly how much more fun Anki is this way. And if it’s fun, you’re much more likely to stick with it. This point is essentially most of the value in reading this guide. Everything from here is less important, so if you’re only going to take away one or two things from this guide, let it be from Part I, and maybe stop reading here.

II. Anki Day 3: Or, Common Mistakes

Moderation

The promise of retaining any information indefinitely, guaranteed, may lead to wanting to ankify pretty much all interesting information one comes across, all of the time. At least this was what I did when I first started using Anki. But this is not a good idea. Firstly, you simply don’t have space for it. If you have a daily limit of 20 cards (you should), you can do max. 2 new cards a day.[3] So maybe think twice before ankifying, e.g., the length of a whale intestine (unless this scores very high on your importance metric, in which case, fair play). More fundamentally, realize that putting cards into Anki is not “free”. In fact, committing to learning even a single card is committing to reviewing that card, and relearning it when forgotten, roughly indefinitely, which is quite a bit of work. It makes sense to prioritize important information because of this. My recommendation would be to start by only ankifying what you feel like you absolutely have to know. And while revising, to ruthlessly suspend any cards that don’t feel like they pay enough rent. If it turns out there is space for more cards, you can always lower your bar for ankification later!

In 1 bullet:

Anki cards are a lot of work; start by ankifying what you absolutely have to know.

Three big memorization mistakes

Once using Anki sustainably, I still made three big mistakes that sabotaged my ability to actually remember learned cards outside of Anki revision. This often meant that all the work of revision was for naught, since what’s the point in memorizing information if you can’t recall it when you need it? I think making these mistakes is essentially the default/obvious way to use Anki. So I hope this section saves someone all that wasted effort!

Mistake 1: Too specific prompts

I think prompts should ideally be as close as possible to the “real life” situation (outside of Anki) where you will want to recall the card. E.g., a bad prompt would be “Length of a whale intestine”. Instead, ask yourself why do you want to know this information? When will you practically want to recall this piece of information? Maybe you like to tell your friends animal fun facts. In that case, a better prompt would be “animal fun facts”. Maybe you are a gastroenterologist(?), and the length of a whale intestine is a constant that comes up in your work all the time(??). Okay, I’m struggling to come up with examples here, but the point is to make your prompt closely model the real situation where you will want to notice, don’t I have a related Anki card here? Otherwise, when the time is ripe to impress your friend with an animal fun fact, you might not even recall that you have a related Anki card. Usually, the default/obvious prompt you may want to use is actually too specific. The real-life prompt will often be vague. E.g., not “length of whale intestine” but “animal fun facts”.

In this context, I should also mention one tempting method of breaking down cards that I think can be a bad idea. Recall the Galileo “level 1” card from earlier:

Why not break this down into super short cards like this?!

Certainly, these cards are more fun to revise since they are so short. However, ask yourself when you might want to recall this information in “real life”. This, of course, is individual, but perhaps a common answer is “when I hear/read the name somewhere, I want to quickly recall what his basic deal was”. If this is one’s answer, one should probably memorize something like the level 1 card. Otherwise, it would be harder to scratch together all the related information in memory, and one might forget some related cards altogether. So if the expected “real-life prompt” demands a longer card, consider making one. Still, it’s a tradeoff, and how to strike it is probably down to individual preference for detailed cases.

In any event, it can’t hurt to do both and, in effect, have multiple cards with overlapping information. This also applies when there are several possible real-life prompts. Redundant cards with different prompts are always a good idea and prevent all sorts of memorization pitfalls, as I will describe further in the next two sections.

In 2 bullets:

Make prompts closely correspond to the real-life situation where you want to recall the card.

Make multiple cards if you have multiple prompt formulations (redundancy is good).

Mistake 2: Putting to-be-learned information in the prompt

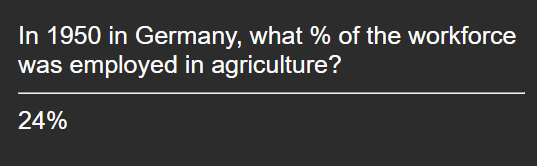

Let’s say you learn that in 1950 in Germany, 24% of the workforce was employed in agriculture and you want to ankify this. You may attempt it like so:

You revise the card and easily recall the answer. So now you should have memorized this fact, right?

Unfortunately, no. Imagine something in “real life” prompts you to recall this fact. E.g., you’re reading about population movement to cities in the 1920s. You think the percentage of people working in agriculture would be a relevant fact in this context, and you recall having a card in your Anki deck about this. The answer was 24%, but what precise year was this about again? As far as you remember, it could equally well be 1920 or 1980. And the number could relate to Germany, or equally well to Britain, or even the world. And was that percent of the workforce or of the whole population again?

As you can see, memorizing just the number (24%) without what that number actually means is pointless here. This is a way to waste your time revising cards without actually gaining knowledge. The problem is that Anki cards only make you memorize the answer, i.e., the back of the card. Therefore, putting crucial information in the prompt is a mistake, and leads to recalling disconnected fragments like “24%” that have no meaning without your Anki prompt. Therefore, all to-be-learned information needs to go on the back of (one or more) Anki cards.

For example, you could reformulate your agriculture card like so:

This also naturally aligns with a less specific “real-life prompt”. It’s more likely that you’ll ask yourself, “What do I know about the history of agriculture?” than “What do I know about 1950s agriculture in Germany?”.

Unfortunately, sometimes real-life prompts don’t work so well without including to-be-learned information. E.g., say you want to memorize something like this:

Recalling “Victorian period” is useless without remembering what century this refers to (was it the 18th or the 19th?), so in principle, the century number should go on the back of the card too.

But this is not a real-life prompt—in most situations, you’ll probably want to recall a specific period, not a general list of periods. Also, this card feels harder because here you additionally have to recall what periods are on the list (though it’s only one here). Luckily, there are three alternatives to just putting everything on the back of the card: Making the card reversible, making multiple similar cards, and using handles.

Firstly, the original “Victorian period” card can easily be made reversible, so the reverse looks like this:

This solves the problem of having the century in the prompt, because it is now also on the back of the reverse card. I would recommend always making a card reversible if that makes any semantic sense at all. This is because foreseeing the three memorization issues discussed in this section is often tricky, and redundancy is a good failsafe.

Secondly, one could also make several more similar cards, each asking for the period name of a different century.

This removes the problem of only remembering “Victorian period” and going “Which century was this again?” (since the Anki cards require you to remember this too). You can even do a lazy version where, for the 17th/18th century cards, the back just says “idk” or “this card is a red herring”.

Thirdly, it’s fine to put to-be-learned information in the prompt if this is part of a >handle, since then it is also on the back of another card. For illustration:

Such a structure can be convenient when you have so much information that you need to use handles for splitting anyway.

Again, it’s a good idea to make redundant cards using several of these four approaches (putting all information on the back, reversible cards, multiple similar cards, handles). Especially when it makes any sense at all to make a card reversible, I would recommend always doing so for redundancy.

In 5 bullets:

Always make cards reversible if this makes semantic sense.

Or put all to-be-learned information on the back.

Or make several similar cards, e.g., “18th century period”, “19th century period”, etc.

Or make to-be-learned information in the prompt into a >handle.

Or do all; redundancy is good.

Mistake 3: Memory shortcuts

Ideally, when you revise an Anki card, you see a prompt, understand what it means (its semantics), and then recall the information that is logically related to that meaning. Unfortunately, our brains like to take shortcuts. So it may happen that you see a prompt, see a unique word in it, or an unusual symbol, or simply recognize its overall visual appearance; skip over the whole semantics part, and immediately recall the correct answer. This is not something you can turn off consciously. And it’s a problem because in real life, you will want to recall the answer without seeing that unique word/unusual sign/visual appearance first.

The idea is to eliminate such memory shortcuts so that you actually have to read the semantics of the prompt in order to recall the answer. Ideally, a prompt wouldn’t have one static syntactical shape at all, but be a different syntactical variation of the same semantic meaning on every revision. But since that would be a painful amount of work, it’s more practical to eliminate memory shortcuts by making prompts as bland and nondescript as possible: Never use images or unusual symbols in the prompt if it can be helped. Don’t use a different font, colors, or other formatting divergences. Don’t use italics/bold/etc. if you don’t usually do this. Don’t use unusual or fancy words where standard ones will do. You get the idea.

For this reason, I also think “cloze deletion” cards are a bad idea: they offer too many structural and visual memory shortcuts.

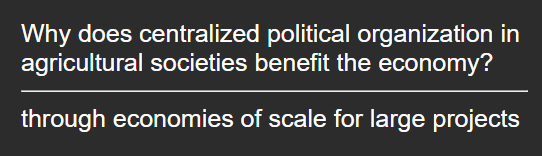

One more note in this vein is to avoid using words in the prompt that also occur in the answer. I’ve empirically observed that these almost always become memory shortcuts/aids for me, but of course, they would not be given to me in “real life”. E.g., consider this card:

Though the words economy/economies are not even used in the same sense here, I would reformulate the prompt, e.g., using the word “progress” instead.

Unfortunately, the brain works in tricky and mysterious ways, and sometimes constructs memory shortcuts even out of apparently completely bland prompts. It’ll find an unremarkable word that nevertheless is used only once in your deck, or a formulation that you’ve used only once within a particular topical context, and that alone will suffice for a memory shortcut, or at least a memory aid. I’ve noticed this happening with as innocuous a formulation as “When did X happen”, when standardly I had used “Date(s) of X”.

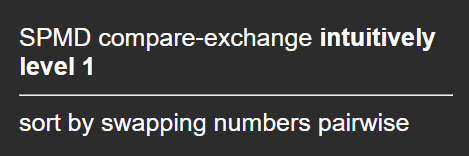

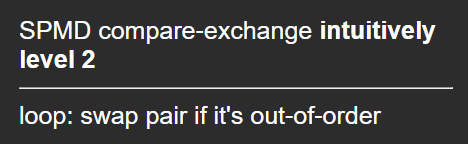

My solution to this is basically to standardize the wording and structure of similar prompts as much as humanly possible. When all your cards asking for dates have exactly the same structure, your brain is going to have to actually parse semantics eventually. A few examples of standardizations I’ve made for illustration:

| ”When did X start/end/happen?” | X dates |

| ”What’s the term/name of X?” | T X |

| ”What person did/was/is known for X?” | who X |

| ”What is the formal definition of X?” (for math stuff) | X formally |

| ”What is the easiest way to understand X?” (for math) | X intuitively |

| ”What are the advantages/disadvantages/ reasons/outcomes of X?” (usually for exam study) | often summarizable as: X pros/cons |

I also usually put any dates at the start of my prompt for consistency.

I recommend identifying types/shapes of prompts that occur often for you and standardizing those in a way you find intuitive. This is not a one-off task. Rather, I recommend doing this constantly, even if you are only creating two or three cards of a similar shape.

Anticipating and preventing memory shortcuts and other memorization mistakes is an imperfect and haphazard art. You won’t always be able to tell what will go wrong in advance. Constant attention to whether you are actually recalling cards when you should in real life is crucial, and you should dynamically improve cards that don’t quite seem to work.

In 4 bullets:

Make prompts as bland as possible.

Don’t use words in the prompt that also occur in the answer.

Standardize recurring types/shapes of prompts.

Keep paying attention to whether you are actually recalling cards in real life & keep improving them.

Aside: Pushback to my approach

Above, I have presented three mistakes that prevent you from actually recalling your Anki cards in real life. However, I should acknowledge some uncertainty in the generalizability of my approach to other people. I don’t generally look over other people’s shoulders (or into their brains) while they use Anki. Moreover, before publishing, I sent a version of this guide to Magdalena Wache, who has used Anki the longest and most prolifically out of everyone I know. (She’s been described as the “Queen of Anki” more than once in my presence.) I will describe her reaction here briefly to give a sense of the way in which this guide is “opinionated” and to show a sensible example of diverging from it.

To my surprise, Magdalena told me that she doesn’t struggle with the three memorization problems as much as I do. Her Anki philosophy is much more about making each card radically short. She rarely makes cards with more than a bullet on the back. So, for example, she would break down the Galileo cards discussed earlier into components of 1-3 words, while I rejected this approach since it doesn’t correspond to the likely “real-life prompt”. (In fact, Magdalena said she wouldn’t memorize Galileo facts at all, but let’s just imagine he was super important to all of us.)

My sense is also that Magdalena has fewer issues with to-be-learned information in the prompt. She said she would gladly use the example prompt “What happened while humans first left Africa?”, whereas I would worry that in real life, I’d recall such a card and then go “Was this before, during, or after leaving Africa?” etc. (Magdalena did say she worries about this too, but to a lesser extent.)

This difference in approach is probably partially due to simple differences in how our brains work. And it’s probably due to different tradeoffs being struck between card shortness and real-life recall of cards. Short cards make revising more fun of course, and allow you to revise more cards. But fast and reliable real-life recall is also desirable. It depends on what you want and how your brain works. You should feel free to diverge from the approach presented in this guide depending on what works best for you. I do want to nudge you to try my approach, though, since it’s so non-obvious that it required five years of trial-and-error to take shape. (This is, after all, an opinionated guide to Anki.)

III. Anki Week 3: Or, Pro Card Design

More detailed opinions on how to make good cards. I’ll first talk about considerations specific to very short cards, two-bullet cards, and long cards, respectively. Then I’ll dive more into how to break down tough “information thickets”.

Very short cards

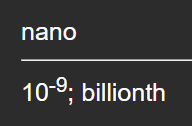

First, I want to reemphasize that, if you can break down a card to have literally one word on the back, do it! This may feel pedantic, but try and see if studying doesn’t become actively fun with such cards. E.g., why have a card like this

if you can have two cards like this

Extremely short cards are especially important if you need to recall a fact really quickly. Having multiple facts on the back of that card would just slow down your recall of the one you need at a given time. In fact, don’t ask me why, but my recall time doesn’t seem to grow linearly in the length of the back of the card. I seem to slow down more than 2x for a double card length. Ergo: Fast recall needs short cards. For facts that I’ll want to recall in <1 sec, the card can generally not be short enough. Examples of such facts are what nano means and what period “Victorian” refers to, which would be super hindering to have to think about every time they come up.

As an aside on very short cards, in my experience, it is possible to push the daily card limit a bit if you have a large enough class of very short cards. I would make these into a separate “easy” deck, also with a daily limit of 10 or 20. Very short cards feel pretty fun to me, anyway. So when revising, I still have one main “hard” deck, and the easier deck feels sort of “free” to revise as well, which means I can revise more cards overall. (But this only works with very short cards.) Example decks I’ve had that worked like this are decks for vocabulary and for memorizing multiplication tables.

Two-bullet cards

I generally try to write each bullet on an Anki card to be a logical unit so that it’s easy to memorize as such. This is a rather minor point, but I wanted to mention an exception I find it useful to make. Often, I find that a two-bullet card, whose bullets aren’t too long, is actually quicker to recall as one long bullet. Don’t ask me why. So, for example, I have changed the following card in my deck

to look like this:

Try it out and see if it makes your recall faster, too. I don’t tend to make many two-bullet cards anymore, at least.

Long cards

Recall that my recommendation for the absolute maximum length of a card is 3 bullets with a total of 18 words. Now, this might just be me, but I find recalling cards of this length pretty hard and unfun. I find myself giving up and closing Anki most often when such a card comes up. I have therefore taken to “staging” the recall of such cards, to recall them bullet by bullet, and check the correct answer progressively as I go. I enable this simply by adding a lot of whitespace at the top of the back of the card, so that the first line will appear at the very bottom of my phone screen, and I can progressively scroll down and reveal more.

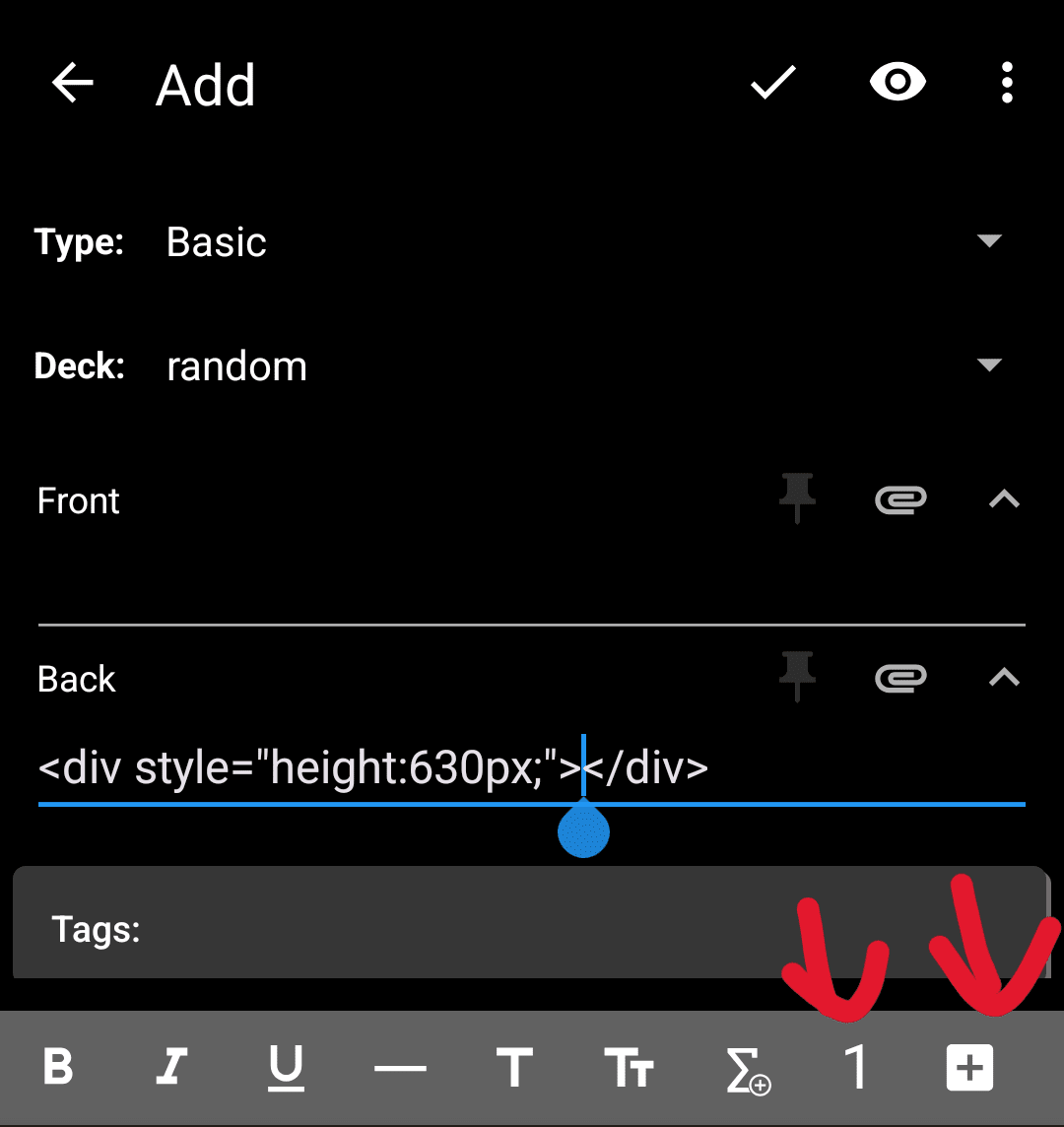

If you want to do the same, on mobile, you can make custom shortcuts to insert text or HTML on cards, so adding whitespace is very quick. I created a shortcut that appears as a “1″ in the below screenshot and produces the following html: <div style=”height: 630px;”></div>

This simply adds an empty block of 630 pixels, which is a bit less than the height of my phone. You can create shortcuts by pressing the “+” you can see on the bottom right in the screenshot.

On desktop, I used the app AutoHotkey (Windows) to make a custom keyboard shortcut. If you want to do this too, I recommend using ChatGPT to quickly write the shortcut script for you.

I’d only really recommend doing this for long cards with three bullets, since staging the recall of short cards in this way just makes your recall slower in my experience.

In 4 bullets:

If you can break down cards to 1 word on the back, do it!

For a <1 sec recall, cards cannot be short enough.

2-bullet cards are usually faster to recall as 1 bullet (if not too long).

Add whitespace to long 3-bullet cards to enable recalling them bullet by bullet.

Ankifying information thickets

The hardest stuff to ankify is rich information “thickets”, e.g., textbook sections, with many interrelations and no obvious linear breakdown. The first thing to say here is that you shouldn’t! You probably only care about 1-2 facts in the whole section, so be ruthless in cutting out the rest. (You don’t have time to memorize all that anyway.) The main situation where you might want to ankify information thickets is probably an exam of some sort. I’ve used Anki for this extensively, so I’m putting my learnings here. But you may not need this at all!

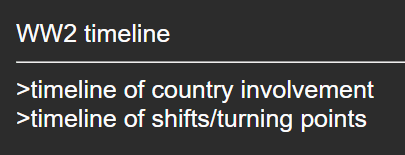

My personal approach to information thickets is to try to find a sort of tree shape in all the interrelated information. The root of this tree is the ultimate motivating theme/what overall question is being answered. The subtrees splitting off from the root, and the subsubtrees, etc., deal with subquestions discussed in the text and/or give increasing levels of detail. The goal is to use this structure to keep each individual node very short and ultimately make short Anki cards. E.g., this is a sketch of a tree based on a text about World War II:

(I don’t write down such a tree explicitly, I construct it in my head while making Anki cards.)

When ankifying such a tree, you would generally want to memorize which child nodes belong to each node. You can do this by adding >handles referring to the children to the node’s Anki card. E.g.,

Sometimes it’s not necessary to do this. For example, I wouldn’t add a handle to the “Level 1” card referring to the “Pacific War dates” card. It’s pretty obvious that the Pacific War must have had a date, so there’s no point in memorizing this connection.

Sequential breakdowns versus multiple levels of abstraction

There are often many possible choices regarding the grouping and subgrouping of information into subtrees. For example, under the “timeline of country involvement”, I chose to split the information into a level 1 and a level 2 subtree. Another, perhaps more obvious grouping would have been to have a subtree per year of the war. However, my general advice is to avoid sequential breakdowns in favor of breakdowns into multiple levels of abstraction. When you think about World War II, you don’t want the first thing you remember to be highly specific details about its beginning; you probably want to remember an overview at a high level of abstraction. Splitting things up in a sequential way often robs you of the big picture. Also, sequential numbers (e.g., years) are not very memorable and are easily confused in my experience.

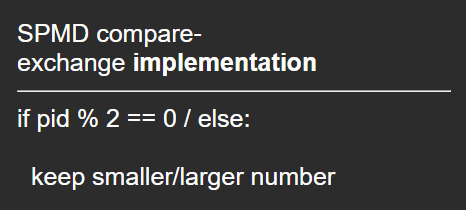

As another example, when studying algorithms in university, I quickly moved away from memorizing them sequentially. Below is a stylized example of how one might memorize an algorithm in three levels of abstraction. (“SPMD compare-exchange” is an algorithm that sorts numbers, but no need to understand the details here.)

Adding missing connections

I should note that after ankifying such a tree, you’re not quite done yet. On the upside, you have ankified all information in one coherent structure. On the downside, this also means that each fact is probably only linked to one prompt and one parent card. In reality, information is interrelated, and one might want to recall a fact in a multitude of related contexts. Unfortunately, just because all your information is now in one tree, this doesn’t mean you will be able to recall the connection between any two facts, in my experience. To make your recall more flexible, you need to add these links. (There may be less linear approaches to ankifying, too, which don’t use a base tree shape at all. I just find it easiest to start with a tree shape and add on a bit of nonlinearity at the end.)

The very first thing you should always consider after making a card is whether it should actually be reversible. Very often, if you want to recall fact X given context Y, you will also want to recall context Y given fact X. Again, if it makes any sense at all to make a card reversible, do it!

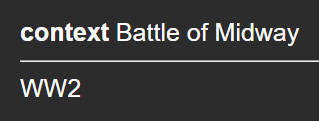

Other than that, the quickest way to add a link between two facts is, again, with a handle. E.g., if somewhere else in your tree you have a card on the Battle of Midway, you can make the “timeline of shifts/turning points” card include that as a handle (even though it’s not a direct child).

Child-to-parent connections

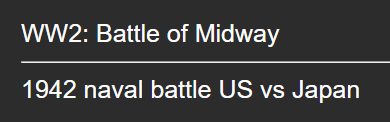

Similar to learning what children belong to each card using handles, you should often learn what parent (or grandparent) belongs to a card. Sometimes this is obvious and need not be learned. For example, you certainly need not learn explicitly that a “WW2 timeline of country involvement” card belongs to a “WW2 timeline” card. However, maybe you’d want to learn that a “Battle of Midway” card belongs to WW2. Unfortunately, this “child-to-parent” connection is not necessarily ready for recall just by learning the “parent-to-child” connections. In general, whenever it’s possible to forget what context a card belongs to, you should make a separate card to memorize this.

I call these “context” cards, but that is just my personal convention.

By the way, I think it’s totally fine to make your actual “Battle of Midway” card easier by providing the “context” in the prompt like so:

This makes your card “shorter” in a sense since you need to recall one less thing (and short cards are good). In the spirit of atomic cards, memorizing the “context” here is split out onto the separate “context card”.

Multiple redundant breakdowns

Sometimes it is actually a good idea to break down a topic in multiple ways, e.g., breaking down the WW2 timeline as in the example earlier, and additionally by year as well. One should always ask, “What will the real-life prompt look like?” Sometimes there are several answers to this, and so several breakdowns make sense. E.g., in real life, a general overview of the war timeline is definitely useful, but sometimes one might also be thinking about a specific year and trying to remember what exactly the state was that year. (Again, although that information is contained in the first breakdown, it is harder to remember since the prompt doesn’t look like the real-life prompt, and the answer might be scattered across several cards.) As another pro, creating redundancy avoids the memorization pitfalls discussed earlier and so makes your recall more reliable.

In 7 bullets:

Find a tree shape in information thickets to break them down into short cards.

Memorize parent-to-child links using >handles.

Memorize (nonlinear) links to other parts of the tree using >handles, too.

Break information into levels of abstraction instead of sequential parts (e.g., years).

Always make cards reversible if this makes semantic sense.

If it’s possible to forget what (parent) context a card belongs to, make a context card.

If 2 possible real-life prompts suggest 2 different breakdowns of information, do both!

IV. Anki Week 5: Or, More Pro Tips If You Still Haven’t Had Enough

Four less essential tips, ordered by how useful I find them.

Save anything for ankification instantly

A little hack that I love is to have a keyboard shortcut that saves any currently selected text to a file for later ankification. I use this so often. Whenever I read an interesting fact or an English word I didn’t know—bam, saved for later. Opening Anki and making a card every time this happens would be an absolute pain. (And therefore, I wouldn’t do it.) Hitting the key combination is entirely automatic by now. I need to go back to the file once in a while to ankify the things, but I actually find this kind of fun, too. (Then is also the time to practice moderation and be ruthless in culling the less important facts!)

If you want to try this, which I highly recommend, you can make such a shortcut with the app AutoHotkey (Windows). I’ll put my AutoHotkey script in a footnote.[4] I recommend using ChatGPT for getting any additional help with this process.

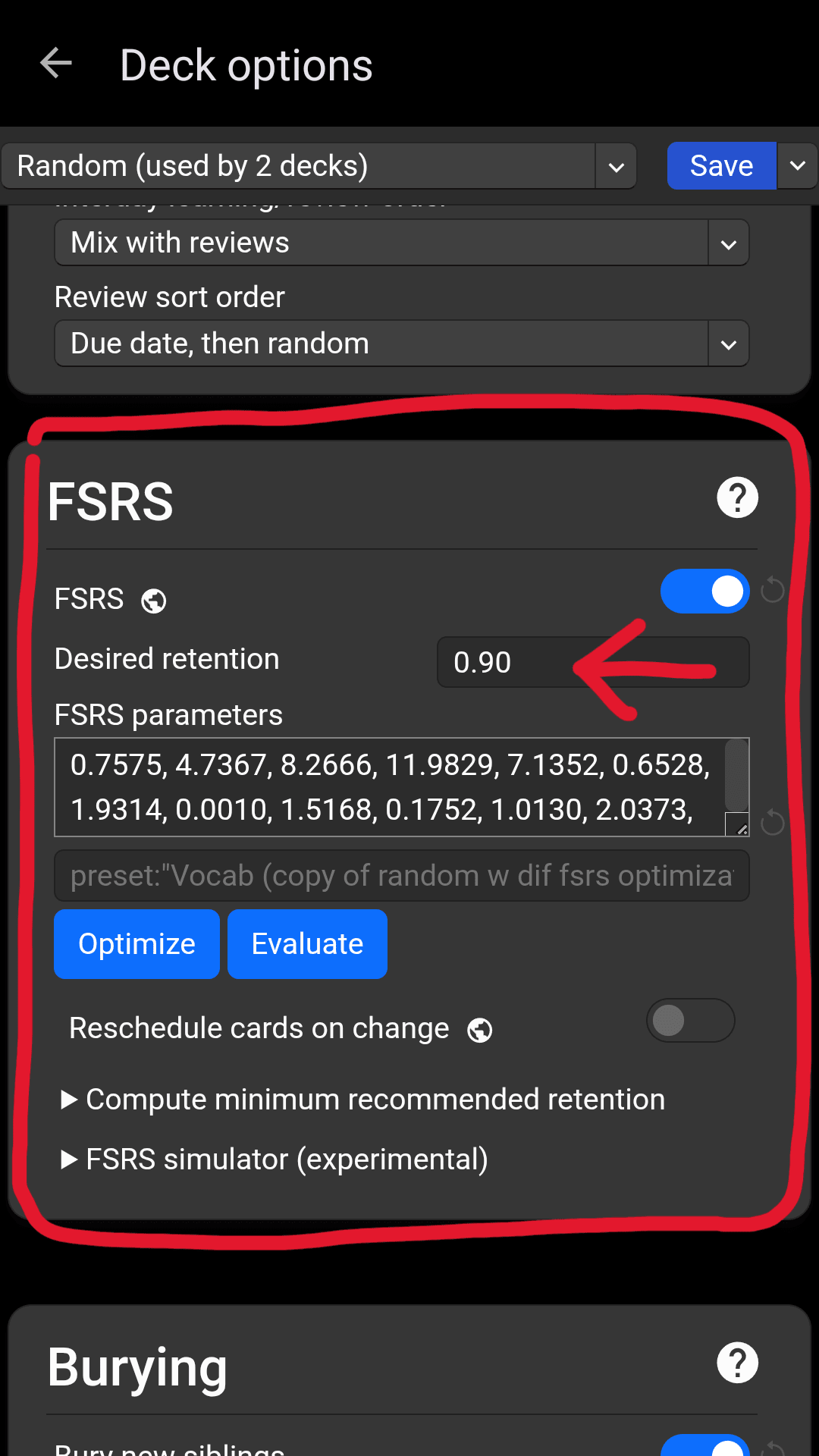

Fix your desired retention rate

By default, Anki will aim for revision intervals/frequencies that give you a 90% chance of remembering each card correctly. However, you can actually adjust this if you want to have a higher (or lower) retention. You can do this by long-tapping a deck > Deck options > scroll down to the “FSRS” box.

Note that if you increase the desired retention, it will result in more revision work. I’ve only ever used this for easy decks where accuracy mattered a lot to me.

Note also that all deck options are applied to deck groups, so you’ll need to make multiple groups if you want differing retention rates.

Spaced reminders

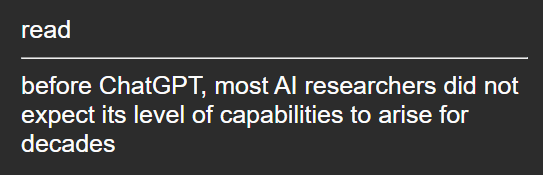

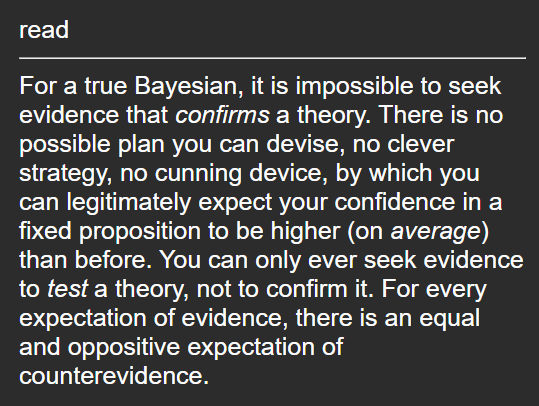

A perhaps unusual way in which I like to use Anki is to periodically remind me of thoughts that could come in handy in many situations, yet that have no particular “prompt” that should trigger them. For example, I have an Anki card that reads “before ChatGPT, most AI researchers did not expect its level of capabilities to arise for decades”. There is no particular situation where I will want to remember this fact, and yet I don’t want to completely forget it either. Ideally, I would like to remember it whenever it is relevant. Admittedly, Anki is not a perfect tool to realize this, but at least I can put a card into Anki so that I reread it once in a while.

Here’s another example:

Make your own card templates and types

As a final tip, I wanted to mention that you can make your own card templates and card types by creating what Anki calls a “note type”. Before getting into this, I first need to explain some Anki lingo. I used the word “card” colloquially in this post, but to not get confused, let me explain how Anki uses words precisely:

A card is a single pair of prompt and answer. That means reversible ones are actually two cards (two distinct pairs of prompt and answer).

A field is one of the input fields when you create cards. Usually, there are two fields: front and back.

A note type is selected when you create a card and defines whether one or multiple cards will be created, and where to put the field values in their prompts and answers. For example, the reversible note type, called in Anki “Basic (and reversed card)”, says 2 cards will be created: One card should have the “front” and “back” field values in the prompt and answer, respectively; the other card should have them swapped:

Note types can even use more than 2 fields or create more than 2 cards.

A note is all the cards created as one unit due to their note type. E.g., the reversible note type creates 2 cards, so these 2 together are 1 note.

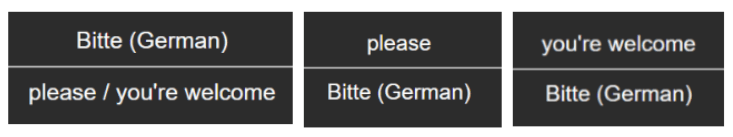

Creating your own note type is useful if you often want to create multiple cards at once that use the same fields in some specific pattern. For example, I have created a note type for the situation where a vocabulary word has two meanings. In that case, I want to create 3 cards in total since I also want reverse cards for each meaning individually. For example:

Having this custom note type saves me the work of creating all 3 cards individually. Instead, I only have to type in 3 field values once (1 word in the source language and 2 different meanings).

While creating your own note type, you can also entirely customize what, besides the field values, should appear on the cards. Here, I simply decided to add a ”/” between the 2 meanings on the first card. But you could also decide, for example, to prepend “2 possible meanings: ” there, or to make the prompt red and bolded, or to add a picture of an iguana to all cards.

For this reason, note types are not only useful for creating multiple cards at once. They can also be used to create templates if you need to create many cards that have text/styling in common. For example, imagine you need to memorize loads of Venn diagrams for some reason, and don’t want to manually create a new Venn diagram image/text representation for every card. You could make a note type defining 1 card and add a generic Venn diagram so you only need to fill in the diagram labels (via fields) per card.

I won’t go into the details of how to do any of this concretely in Anki. I think it’s most useful to know that it is possible, and you can go find out the details if and when you need them. (I recommend ChatGPT for this purpose.)

In 5 bullets

Create a keyboard shortcut to save any selected text for ankification instantly.

You can adjust your desired retention rate per deck.

Make cards for thoughts that you’ll want to remember in many situations, but that don’t have a particular associated prompt, to be reminded of them.

Create a note type if you often need multiple cards that use the same fields.

Create a note type if you need to create many cards with shared text/styling.

Conclusion

If you have read this far, it may be best to remind you that the most important part of this guide is Part I. Most people never get over the initial hurdle of actually using Anki long-term. So if you only take away one or two things from this post, let them be about making a sustainable and fun Anki habit: Keep few cards and keep them short. Having fun is important to stick with Anki long-term. Everything else in this post can be dealt with once that’s in place!

I’m very interested in additions or pushback to my advice in the comments. As a final side note, I’d also be interested if anyone has made/wants to make shareable AI safety or EA-related Anki decks. If so, please comment! I at least would love to use/contribute to something like this!

I’m grateful to Oscar Delaney, Jeremy Gillen, Magdalena Wache, Inés Fernandez, and Neel Alex for their Anki experience and comments, and to Leon Lang for a fortunate introduction.

- ^

Anki will tell you if your daily new card limit exceeds what is sensible given your daily review card limit.

- ^

Freely made-up number

- ^

If you have a daily limit of 20 cards, but add more than 2 new cards a day, your revisions won’t keep pace with your adding cards (as mentioned in the section “Too many cards”).

- ^

My AutoHotkey script for saving any currently selected text to a file

; Define the file to store saved texts

SavedTextsFile := “C:\...\saveForAnki.txt”; Hotkey to save selected text (Ctrl+Shift+S)

^+s::

; Copy the selected text to the clipboard

Send, ^c

Sleep, 200 ; Wait a moment for the clipboard to update

SavedText := Clipboard; Trim whitespace from the saved text

SavedText := Trim(SavedText); If clipboard is not empty, save it to the file

if (SavedText != “”)

{

; Ensure the file path is valid

if (!FileExist(SavedTextsFile))

{

FileAppend, , %SavedTextsFile% ; Create the file if it doesn’t exist

}; Try to append the text to the file

try {

FileAppend, %SavedText%`n`n, %SavedTextsFile%

} catch {

MsgBox, 16, Error, Failed to save text. Please check file permissions or path.

}

}

else

{

MsgBox, 48, Warning, Clipboard is empty or contains invalid data!

}

return

Thank you for writing this! It’s great to see someone tackling Anki methodology in depth. I’d like to add my currently held beliefs about what makes for well-designed Anki cards and good practices. These are stated in definitive terms to make the critique tangible, though I acknowledge this means sacrificing some nuance.

Against the “Levels” System

The “level 1, 2, 3” hierarchy presupposes meta-knowledge about your knowledge. I think this risks wasting cognitive resources tracking what you know instead of learning more. I prefer closed-ended questions with single correct answers.

More Cards is Better

A couple of people have mentioned it here, but 2 new cards per day is very aggresive. I probably agree with Nielsen/Matuschak that you should make “more cards than you think you should.” While there are diminishing returns, there are also diminishing costs. A tightly interconnected web of facts has better retention than isolated ones.

Redundancy is a Feature

Hard agree with this point you make. Cards reinforce the pattern “circumstances → solution.” Multiple cards with slight prompt variations (epsilon changes) help you recognize solution spaces more generally. This is underappreciated.

Against “Everything on the Back”

This creates open-ended questions with multiple valid answers. You end up harshly reinforcing one answer while “forgetting” others that are technically valid (if this is really the preference, then it is hard to say anything against). Better alternatives:

Reverse cards (both-sides definitions)

Separate cards for object names vs. properties

Cloze Deletion: Format vs. Application

I disagree that clozes are bad. Every card type is technically cloze deletion (if there is any point in getting pedantic). Your real issue therefore (I assume) isn’t the format but excessive context, which leads to remembering “visual shape → answer” instead of “semantic meaning → answer.” Is this accurate do you think?

Practical Deviations

I break the 18-word limit regularly—mathematical theorems need their assumptions. I make one card for results, separate cards for assumptions. I also skip parent-child memorization by embedding more context directly in cards. This might be the fundamental tradeoff.

If you have run into any of these issues in your own practice or believe them to be non-essential, then I would be happy to know

I find it a lot easier to memorize content with an “Everything on Back” approach, but I have encountered the problem you’re talking about. Usually, if this starts happening though I go back and merge the cards I’m having issues with. So you can kind of have both approaches at once, if you’re willing to edit your deck aggressively.

I think this is really common, even if you are not using the “Everything on Back” approach. If I had to give it a name, I would go with “interference”, which seems to be the name from 20 Rules. This is not an endorsement of the 20 rules.

I previously used Obsidian with an Anki plugin for syncing to Anki one way (this also allowed card updates from Obsidian to Anki, but not the other way–hence one way). The upkeep became too heavy. I have since been trying to keep upkeep to a minimum.

I will update a bit however, since more people have now mentioned the same thing. Perhaps I am just doing something wrong. Thanks for sharing:)

as a datapoint: I do an average of 60 reviews per day these days, down from my peak of 400/day or so (which lasted about a year), and 200/day when I was first starting. I don’t generally form habits easily, and I am generally extremely procrastinatory, but I’ve basically never missed more than a few days of Anki in a row since I started nearly 7 years ago. So I think this habit is especially robust once instilled, and once you can reliably do 20/day you should slowly ramp up to more and more.

What things do you tend to have in your Anki decks?

languages, math, cs, music, miscellaneous knowledge

What’s your total lifetime review count? (Stats → Collection/All Time → Reviews)

319,892

Oh also how many mature cards? (from the same window)

I’m in a similar situation to to leogao (low conscientiousness but found it easy to install the habit) and have 432,864 lifetime reviews, 15,414 mature cards.

another useful tip: you can put arbitrary javascript on cards, do you can do stuff like randomize the font size or make minor wording tweaks or whatever to avoid overfitting

After reading this comment I choose to make my font random (within a class of six readable ones). I normalised font height, but my line sizes are now all jumbled (I use max 50ch because I use my phone for Anki). Will probably keep this change indefinitely.

I really like this idea. Thank you so much for sharing!

glad it was helpful!

Please give an example of JavaScript code that would make a minor wording tweak. I often find I need to not memorize the cue so precisely.

After fighting with Claude and O3 for a while I managed to get the following:

1. Create a new note type

Go to Tools → Manage Note Types (or hit Ctrl-Shift-n)

Click “Add”

Select “Clone:Basic”

Name it “Basic (randomized prompt)”

Click OK

2. Edit the Card Template

Click cards (Tools → Manage Note Types → select “Basic (randomized prompt)” → Click “Cards”)

In the Front Template panel, replace all content with:

Front Template Code

<div id=”q”></div>

<script>

(function () {

// Raw contents of the Front field, with any book‑end <br> removed

const raw = `{{Front}}`.replace(/^\s*<br\s*\/?>\s*|\s*<br\s*\/?>\s*$/ig, ″);

// Utility to turn the raw string into an array of clean prompts

function parseVariants(txt) {

return txt

.split(/;\s*<br\s*\/?>\s*/i) // split ONLY on ”;<br>”

.map(s ⇒ s.replace(/^\s*<br\s*\/?>\s*|\s*<br\s*\/?>\s*$/ig, ″).trim())

.filter(Boolean);

}

/* ---------------------------------------------------------

Tiny cache that persists while a single Q‑A pair is on

screen, but is *cleared* as soon as you flip to the back,

so the next time the card appears it randomises anew.

--------------------------------------------------------- */

window._ankiPromptCache = window._ankiPromptCache || {};

const onAnswerSide = !!document.getElementById(‘answer’); // <hr id=”answer”> exists only on back

const needNewPrompt = !onAnswerSide || !window._ankiPromptCache.prompt;

if (needNewPrompt) {

const variants = parseVariants(raw);

window._ankiPromptCache.prompt = variants.length

? variants[Math.floor(Math.random() * variants.length)]

: raw; // fallback if nothing splits

}

// Show the prompt selected for this Q‑A pair

document.getElementById(‘q’).textContent = window._ankiPromptCache.prompt || raw;

// Once the answer side is rendered, invalidate the cache so the *next* visit re‑randomises

if (onAnswerSide) {

setTimeout(() ⇒ { window._ankiPromptCache.prompt = null; }, 0);

}

})();

</script>

In the Back Template panel, replace all content with:

Back Template Code

{{FrontSide}}

<hr id=”answer”>

<div id=”a”>{{Back}}</div>

<style>

/* Hide the single auto‑inserted <br> Anki places after <hr> */

#answer + br { display: none; }

</style>

3. Make a card

Create a card of type “Basic (randomized prompt)”

In the Front field, the different prompt variations should be separated by a semicolon followed by a new line. An additional blank line separating variations is optional:

or

The formatting will be messed up if you have all variations on the same line, or have whitespace after the semicolons, or have more than one blank line between questions.

Put the answer in the Back field like usual:

Thank you that works as desired!

Thank you for an interesting guide!

I used Anki very differently than you do, and I used it consistently for many years, totalling more than 30,000 card reviews. (We’ll get to why I stopped.) My learning was focused on foreign languages, which is a special case.

If I had to boil down my advice:

Make card creation as easy as possible. This may mean building or using special tools.

As you said, limit new cards to 10-20 per day.

It is almost impossible to make a card too easy to be useful. For example:

Put an interesting snippet of foreign language text on the front. Boldface one word. If you understand roughly what the boldfaced word means in that context, pass the card. You’re not obligated to read all the text. (Credit to Khatzumoto for this idea.)

Alternatively, cloze (hide) one word on the front. Or better, just half the word. If you can recall the word, pass the card.

Use automatic tools to convert subtitles & audio into cards. If you can understand at least 80% of one subtitle, pass the card.

Most importantly, once you make it easy to create lots of cards, and once you make the cards easy to answer, then the final Anki skill is to DELETE DELETE DELETE cards at the slightest provocation. Cards are cheap! If a card annoys or frustrates you, delete it! If you need to learn that information, you’ll eventually encounter it in a better context and turn it into a new card.

In fact, consider deleting cards instead of failing them. Or set cards to auto-suspend if you fail them twice.

Most of the high-value learning occurs in the first 30-40 days. It’s OK to keep older cards if you like them! But if you’re not learning any new cards, and you’ve just been reviewing old cards for a couple of months, it’s fine to just suspend entire decks.

This approach to Anki may seem unfamiliar! That’s because it’s based on a different philosophy:

The normal way to use spaced repetition software is as a database of facts to memorize. The goal is to learn almost everything.

The philosophy I describe above is using Anki as a memory amplifier. The goal is to “turn up the volume” on interesting knowledge, particularly linguistic knowledge. But even with the volume cranked, many signals will still be too weak. And that’s OK!

I strongly suspect that selective forgetting is closely tied into how the brain generalizes. Trying to remember everything feels slightly unnatural. Trying to remember more and to generalize better can work quite well.

Ohh I love this and it is indeed very different from what I do! I’d be super interested in a wee writeup on what non-language learner Anki users can learn from this approach, if you ever have the time for that. Maybe there’s a hybrid approach with the best of both worlds? (Also lowkey interested in why you stopped now!)

Oh, sorry! I stopped because for the language I cared the most about, I had reached a point where natural use of the language was enough to maintain at least 90+% of college-level reading skills. If I go too long without doing enough reading, then I start to miss obscure vocabulary in difficult texts. So when doing Anki reviews on old decks became tedious, I followed my advice and suspended my decks!

Adapting to non-language areas. If I were going to try to adapt this language-focused “memory” amplifier approach to other areas, I would start by experimenting with new card formats, looking for new embarassingly easy formats. I don’t know exactly what would work. But let’s try an experiment!

Keeping with your example, I asked ChatGPT to summarize a Wikipedia article about Isaac Newton. It gave me this (I have manually removed the citations and header/footer text):

Turning this into a card. This feels like a good time to use cloze cards, because they’ll let us autogenerate a bunch of easy cards from the base text. Let’s split this into two cards, and add Anki cloze markers. Here’s how I might mark up the second:

For those unfamiliar with cloze cards, this will generate 4 cards, each hiding the information marked with c1 through c4, respectively.

When reviewing each card,

You are in no way obligated to read anything other than what you needed to fill in the blank.

If you can fill in the blank, mark the card correct.

Note that these are all stupidly easy:

c1: “calculus” is a gimme, especially thanks to the mentions of infinitesimals and Leibniz.

c2: I only hide the first two digits of the year. And “17” is left unhidden elsewhere. Usually getting people in right century is good enough, so why stress over it? Or you could hide the decade digit if you were focusing on a specific century.

c3: “prism” is pretty obvious from context, but just in case, I leave the “p” visible.

c4: I leave “ref” visible, and you need to remember it’s “reflecting”, not “refracting”, but that doesn’t require more than basic physics knowledge.

Predictions. My hypotheses:

This style of card can be created very cheaply, especially since cloze gives you 4 cards for the price of 1.

You will retain a surprising amount of information about Isaac Newton.

You will (and should!) delete a bunch of these cards within a month or two, and not really feel the loss.

Reviewing these cards can be very low stress, especially since you should have a hair-trigger delete.

Possible objections:

“Doesn’t seeing the same information on multiple cards mess with the spaced recognition algorithm?” Surprisingly, this seems to matter less than I expected. We’re focusing on amplification, not flawless memorization.

“Would you actually use an LLM to generate initial summaries?” Possibly, at least if I could get the hallucination rate low enough. I might also copy-paste interesting bullet points from various places.

“Aren’t these cards too easy?” The more Anki reviews I did, the more I started to suspect “too easy” wasn’t actually a thing.

Anyway, like I said, this is mostly guesswork! I would be fascinated if someone wanted to create (say) 10-20 base cards this way, with 3-5 clozes each, and review them for at least 40 days, then report back. But I hope this provides some useful ideas to someone!

The problem with these cloze cards is that you tend to link the shape to the information rather than the words themselves. After a few goes you’ll basically stop reading the words entirely. It’s not very effective for recalling the facts irl, since usually you’ll be trying to recall the answer to a specific question (prompt), not fill in the blanks. I find that the things the OP talks about in the above guide are much better for actually recalling info when it counts.

As an aside, the philosophy of impulsive deletion/suspension from your main comment seems like a promising idea. I typically take the opposite approach and don’t even suspend leeches, with that being exclusively for useless or obviously-defined words. I might try it out if I go about learning another language though, it definitely has potential (though it also seems far more suited for high-immersion learners which isn’t something I’m good at).

I think you might have misread that part, the post is advocating 10-20 review(!) cards per day and only 1-2 new cards

Huh, I suppose. My card formats (see sibling comments) are easy and fun enough that reviewing 50-100 cards takes 15-30 minutes, and it’s not especially high stress.

But then again, like I noted above, I delete cards pretty ruthlessly if they’re obnoxious to review.

I think this was fine with the old anki algorithm, but less so with FSRS.

It’s sensible a priori to expect that your forgetting curves for birthdays and math are different. If you optimize parameters for a single deck, anki will treat every card in the set {birthdays, math, historical trivia} the same. But if you have separate decks (and deck groups) for each topic, FSRS will be able to extract more signal and pick better parameters.

Admittedly, using a single deck probably isn’t a huge mistake, but it seems like an unforced error to me.

you can use subdecks and get best of both worlds

both good points, thank you!

Curated. I’ve periodically attempted Anki and bounced off. This post got me somewhat excited to try again, feeling a bit more in control of it this time.

The “keep it short” advice certainly resonates. The ideas on how to handle “knowledge thickets” felt practical and useful.

Ironically I do think it might have made more sense to break it into multiple posts, not only because it’s quite long and each section felt reasonably self-contained, but also, I think there’s a “space-repetition” like principle on LessWrong where, like, people are more likely to absorb an overall idea if it’s repeated across multiple days/weeks on LessWrong.

I do wish this post felt more oriented about why you might want to be using Anki. I like the focus on “what’s a realistic trigger”, but most of the examples felt kind of random and not like facts I’d actually likely want to remember. (By contrast, I liked Turntrout’s old post on Self Teaching which presented Anki in a more goal-directed way)

thanks Raymond! agree this post would be better if it was split up & repeating things, more like approximating a “course”. this was just the level of effort i happened to feel inspired to put in.

my mission with this post was mostly to fix problems if one IS using Anki, not to convince anyone to use it. since writing, responses have seemed like the why might’ve been interesting for several people tho!

I’d expect what your goals are to have a pretty noticeable effect on how to optimize your anki.

My favourite tip I rarely see mentioned in Anki discussions: add a hidden source field to your custom card template and paste the original source or reference or hyperlink it.

This is useful for several reasons:

You can easily find the source to read more about the subject simply by editing the card in the app.

You don’t have to clutter the card with info about the source if it is not essential to the card.

In addition to the source info, you can add your own notes about why this information was useful or why you chose this specific source etc. You can give additional context such as “This principle was explained to me by Person X when we talked about Y”

Keep in mind you can save large amount of info in the field since it is not supposed to be visible during review and text and images take relatively little space on devices nowadays. Thus you can copypaste entire paragraphs/pages and multiple pictures etc[1] to have the source info easily accessible without having to the original source later, it makes it easier to:

edit the card later if you find it confusing or unclear.

read the original context where the thing was discussed or explained.

(edit: added a missing word)

If it is based on or created from an LLM conversation or an LLM summary, likewise you can just copypaste the conversation there, not just hyperlink it.

Great post! I used Anki religiously during the first few years of my undergrad but eventually fell out of the habit, mostly because making new cards became too time-consuming. (I wish I had come across advice like this back then!)

A few anecdotes from my own experience:

For math, I naively created cards that covered my first-year real analysis and linear algebra lecture notes in extreme detail. I used a custom card template that supported LaTeX, and many of the cards required me to prove theorems or solve problems. Despite how tedious they were to make, I actually enjoyed them. They forced me to whiteboard solutions and gave me reasonably quick feedback.

While I wouldn’t recommend this approach (it was incredibly time-intensive) reviewing those cards has consistently been a uniquely rewarding experience.

They trigger a kind of mental time travel, vividly bringing back both the content and mindset I was in when I created them. More than anything else, they help me reconnect with a sense of intellectual curiosity and creativity that I often struggle to access otherwise.

One experiment I tried was adding images to the back of my cards to aid recall. For language learning, I wrote a Python script to scrape Google Images for vocabulary terms. For math and CS, I’d usually hand-pick images.

I have mixed feelings about how well this worked. I can still recall some of the images, but not always the questions they were tied to. Still, they sometimes help me recall the general “neighborhood” of related cards. Curious if anyone else has tried this and what their experience was like.

Ironically, the deck I learned the least from was my computer science one, which makes sense in hindsight. The cards were often too large and passive. Unlike the math ones, I didn’t design them to actively engage with the material.

Looking back, I wonder how things might’ve changed if I had created cards that asked me to implement things, maybe even with runnable code snippets on the back.

I think the biggest hurdle for me in getting back into Anki has been not knowing what information is actually worth the effort to memorize. Reading this made me realize that creating really small, focused cards might make that question feel a lot less “all or nothing.” I might give it another shot :)

I think you could have separated this into two posts, or even a sequence. Part 1 is very beginner friendly, but later parts have tips that were novel to me (For reference, I’ve been using SR for ~3 years).

I think it would be most accessible/searchable as a sequence.

That’s an interesting post, thank you! I’ve also been using Anki for a long time. I started in 2018. Now I do about 70 reviews a day (just checked my stats in Anki). The downside of your system, imho, is that it doesn’t integrate with other notes, like notes for books, one’s published posts, ideas, etc. And your handles from the cards looks an artificial and unmaintainable solution that won’t last long, I think. I found it useful to have one system organized around plain text (markdown). I create my anki cards from those plain text files using this script. Other than that, I liked the idea of short cards, and your other advice.

Also, I’m suspicious about effectiveness of sharing personal Anki cards because personal associations matter a lot for retention and recall. I found this article useful.

I also do this! I like to take freeform notes in Obsidian (e.g. for part of a textbook) and then at the bottom create Anki cards. It’s really nice being able to edit/update related cards from the same place, and particularly the same place as the raw context.

By default, Anki uses SM-2 algorithm, which doesn’t aim for any retention level.

the image shows that you don’t have a distinct card front, so how do you judge whether to pass or fail the card?

Is it by how familiar the thought is, by how readily you think you would remember this when you need, by looking at the projected intervals and deciding which interval you want, or something else entirely?

Thank you for writing this post. It has a lot of great advice I want to internalize, so I did the recursive thing and made Anki cards for it. But I had some trouble following your advice while ankifying your advice.

The tricky rule is:

Even after very aggressive cutting, this card violates the rule (it has 4 logical bullets and 20 words):

I am not sure how to break this down further. Do you (or any other veteran Anki users) have advice?

This is seperate from my feedback and just an addition that really helps me: If you plan to do like 100 cards in one day, find yourself a calm straight path through some natural environment, and learn the cards while walking there. This is the type of multitasking that, in my opininion, mostly has benefits. The natural envirnoment is good for your psyche, you get some healthy steps in, and it’s only a teensy bit slower. I cannot recommend it enough and do it every time I have to study a lot of cards for an exam.

Related; from the founder of Supermemo and a pioneer in SRS: https://www.supermemo.com/en/blog/twenty-rules-of-formulating-knowledge

I think “20 cards a day” might be too aggressive, but I decided (after taking a shower and realizing that learning thirty new concepts a day is extreme) to lower the presets for my 2 decks (French and Mandarin Chinese) to 5 new cards and 50 review cards per day. Previously, it was 15 new cards and 150 reviews. I even finished one of the decks, which is kind of crazy.

Amazing guide! I only wish I had read it earlier.

This post made me start using Anki and one month in, I really enjoy the process! Looking forward to re-visit the post and all thoughtful comments to see how I can improve my usage further.

I’ve never tried Anki but thank you so much for the way you’ve written this post. The precise moment I find a topic that I’m convinced is worth Anki-fying[1] I’m going to try it.

The way you’ve structured the post is really helpful – the whole accordion format: introduce an idea expand upon it, and then bullet point it.

I’m always skeptical about any note taking or memorization system – but you’ve raised a good counter which applies to not just Anki: don’t make prompts overly specific. Great advice. General advice. That is always my question, and again, why I haven’t tried Anki (yet?): when will I use this in real life?

But this post is a wealth of techniques on how to structure those cards – using bland prompts, always breaking down things, useful heuristics for words per card or number of cards to read per day etc. etc.. And they are only heuristics – your tone is very permissive.

Great post because it contains a lot of practical, nitty gritty execution details, and is well structured and doesn’t feel too dogmatic even if it’s “opinionated”.

“Friend’s birthdays” now that I don’t use Facebook anymore that is a realistic and useful thing to memorize. Hmmm

I’ve been learning with Anki for Exams for Years now and I have never managed to keep learning them after the exams. I’ve been using very few cards, and been splitting them more and more, but I guess not enough.

In my experience, however, some bigger cards are needed against frustration, but to be kept at a minimum. I call them ‘Overview Cards’. For instance, if you split a mathematical proof into bite sized chunks, the way I inferred from your post would be to have a card ‘Step after X’ between every two steps. This worked well when the intervals were small, but with larger intervals (and the random ordering the anki scheduler injects) I found myself losing track of the overall structure of the proofs. I then had to go back to browsing to find the linear sequence. I find this more exhausting than just learning the structure of the proof. Please tell me if you had experiences that contradict my observation :D

Simplifying these Cards with the tree-method is useful, though. Hierarchical organization is everything!

Talking of Hierachical Organization: You can Store it all in a Big Ol’ Card Container, but use subdecks! They can be a useful addition to the prompt if your front side is too ambiguous (e.g. definitions of variables). In your card template, just include {{Deck}} with smaller font size and lower opacity above your {{Front}}. You can also include a subchapter field to your cards, and include it the same way. Just make sure that the subchapter is not the literal solution to your prompt, this happened to me once or twice.

Next, concerning the prompt types. While you should not color the prompts themselves, you can indeed give specific colors to prompt-types you often use. For example “context” can be blue and so on. This does not lead to overfitting in my experience, but reduce cognitive load in recognizing the prompt types. (And colors make everything better for ADHD folks by just being more stimulating. (source)[https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1087054711430332])

Great post!

I think I’d argue something similar but distinct at the beginning. My impression is that people only quit anki for one reason, and that reason is that they don’t like it. All “how to stick with anki” advice is only useful insofar as it makes anki more fun or enjoyable. I genuinely look forward to my reviews (almost) every day. Sometimes I do a lot, sometimes I do a little.

The 20-card/day limit is probably more useful at the beginning, when it can be tempting to try to add in tons of new cards. But more reviews can be fun too! I don’t have a hard limit, and I think I do something like 40-50 reviews/day (and often at the end I still want more!) There’s definitely such a thing as too many reviews, but that threshold is different for everyone. I’d recommend everyone reading this to test their limits, but as soon as you get annoyed, move back into easy-mode.

Also, I’d like to second @Random Developer that knowing to DELETE cards with little provocation is essential to making anki fun. If your cards are annoying, you will start to associate that annoyance with anki more generally. If you are annoyed with anki, you’re more likely to drop it.

From my own experience, the closest I came to deleting anki was when I was trying to learn a bunch of esperanto quickly, doing hundreds of reviews/day (and getting many of them wrong) and became annoyed with it. I tried to push through, but I started to not want to do my other reviews, either. One of the best decisions I ever made was giving up and deleting that entire deck. I think I would have slowly faded away from anki in general if I had stuck with it for a few more weeks. “You must not dread anki; you must not treat it like a chore. If a card causes you to avoid reviewing, gouge it out and throw it away. It is better to give up on one card than to lose the benefits of spaced repetition forever.”

Actually interested in your post and spaced repetition (SR) techniques, although I am not a specialist. I had no idea what means: “Anki,” but it was on my LessWrong feed, so I gave it a look.

Consider adding a brief line to the intro—for those who, clueless like me, find their way to your post.

Something to identify what it is and most important acknowledge the developer—like: Anki is a free, open-source flashcard program that utilizes spaced repetition and active recall to help users memorize information effectively.

Elmes, D. (2024). Anki (Version 2.1.66) [Software]. https://apps.ankiweb.net/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anki_(software)

Apologies if this is too basic or repeated elsewhere.

Thank you for the post.

Leo

Do you use any technological method for making it easy to look up these handles? I am a long-time user of Obsidian for note-taking, and there is a great Obsidian_to_Anki plugin which allows for creating and managing Anki cards as part of one’s Obsidian notes and it inserts functional links on both Desktop and Android.

It might also integrate well with the AutoHotkey script that you use.

I have not kept up my Anki usage after setting it up once and will now try again. I really did find it extremely demotivating to find the “400 cards due” every time I did get myself to open Anki.

Thanks for the great tips!

Thank you and best of luck with the renewed Anki attempt!! I don’t have “functional” handles like in Obsidian and haven’t really felt the need to. But I hope you get that to work with your setup!

It seems like there could be so much upside from building out tools for spaced repetition that anki just isn’t going to deliver. For example

- llm assisted card re-writes

- audio and voice testing (akin to a viva voce)

It also seems plausible that the progress of spaced repetition algorithms has been stunted by the fact that one company isn’t actively trying to make it better. A cloud type anki, where a company has visibility over forgetting curves, long term habit tracking, etc would probably deliver a better product for the type of learning most people are searching for.

Do people tend to entirely create their own decks of cards? Or are there “ready made” ones you can download online?

I get the impression creating your own decks is pretty common, but there are also a ton of shared ones at https://ankiweb.net/shared/decks.