I Would Have Solved Alignment, But I Was Worried That Would Advance Timelines

The alignment community is ostensibly a group of people concerned about AI risk. Lately, it would be more accurate to describe it as a group of people concerned about AI timelines.

AI timelines have some relation to AI risk. Slower timelines mean that people have more time to figure out how to align future intelligent AIs, potentially lowering the risk. But increasingly, slowing down AI progress is becoming an end in itself, taking precedence over ensuring that AI goes well. When the two objectives come into conflict, timelines are winning.

Pretty much anything can be spun as speeding up timelines, either directly or indirectly. Because of this, the alignment community is becoming paralyzed, afraid of doing anything related to AI - even publishing alignment work! - because of fears that their actions will speed up AI timelines.

The result is that the alignment community is becoming less effective and more isolated from the broader field of AI; and the benefit to this, a minor slowdown in AI progress, does not nearly outweigh the cost.

This is not to say that trying to slow down AI progress is always bad. It depends on how it is done.

Slowing Down AI: Different Approaches

If you want to slow down AI progress, there are different ways you can go about it. One way to categorize it is by who a slowdown affects.

Government Enforcement: Getting the government to slow down progress through regulation or bans. This is a very broad category, including both regulations in a certain country vs. international bans on models over a certain size, but the important distinguishing feature of this category is that the ban applies to everyone, or, if not to everyone, at least to a large group that is not selected for caring about AI risk.

Voluntary Co-Ordination: If OpenAI, DeepMind, and Anthropic all agreed to halt capability work for a period of time, this would be voluntary co-ordination. Because it’s voluntary, a pause around reducing AI risk could only affect organizations that are worried about AI risk.

Individual Withdrawal: When individuals concerned about AI risk refrain from going into AI, for fear of having to do capability work and thereby advancing timelines, this is individual withdrawal; ditto for other actions that are not taken in order to avoid speeding up timelines, such as not publishing alignment research.

The focus of this piece is on individual withdrawal. I think nearly all forms of individual withdrawal are highly counterproductive and don’t stand up to an unbiased cost benefit analysis. And yet, individual withdrawal as a principle is becoming highly entrenched in the alignment community.

Examples of Individual Withdrawal in the Alignment Community

Let’s first see how individual withdrawal is being advocated for and practiced in the alignment community and try to categorize it.

Capabilities Withdrawal

This is probably the point which has the most consensus: people worried about AI risk shouldn’t be involved in AI capabilities, because that speeds up AI timelines. If you are working on AI capabilities, you should stop. Ideally no one in the field of AI capabilities would care about AI risk at all, because everyone who cared had left—this would be great, because it would slow down AI timelines. Here are examples of people advocating for capabilities withdrawal:

Zvi in AI: Practical Advice for the Worried:

Remember that the default outcome of those working in AI in order to help is to end up working primarily on capabilities, and making the situation worse.

Nate Soares in Request: stop advancing AI capabilities:

This is an occasional reminder that I think pushing the frontier of AI capabilities in the current paradigm is highly anti-social, and contributes significantly in expectation to the destruction of everything I know and love. To all doing that (directly and purposefully for its own sake, rather than as a mournful negative externality to alignment research): I request you stop.

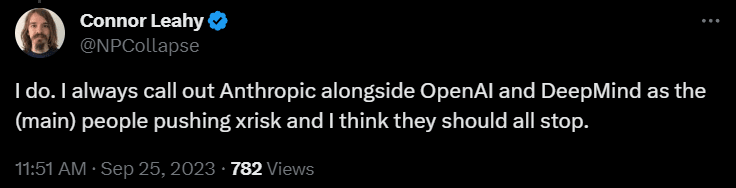

Connor Leahy:

Alignment Withdrawal

Although capabilities withdrawal is a good start, it isn’t enough. There is still the danger that alignment work advances timelines. It is important both to be very careful in who you share your alignment research with, and potentially to avoid certain types of alignment research altogether if it has implications for capabilities.

Examples:

From Miri, in a blog post titled “2018 Update: Our New Research Directions”, concern about short timelines and advancing capabilities led them to decide to default to not sharing their alignment research:

MIRI recently decided to make most of its research “nondisclosed-by-default,” by which we mean that going forward, most results discovered within MIRI will remain internal-only unless there is an explicit decision to release those results, based usually on a specific anticipated safety upside from their release.

This is still in practice today. In fact, this reticence about sharing their thoughts is practiced not just in public-facing work but even in face-to-face communication with other alignment researchers:

I think we were overly cautious with infosec. The model was something like: Nate and Eliezer have a mindset that’s good for both capabilities and alignment, and so if we talk to other alignment researchers about our work, the mindset will diffuse into the alignment community, and thence to OpenAI, where it would speed up capabilities. I think we didn’t have enough evidence to believe this, and should have shared more.

Another example of concern about increasing existential risk by sharing alignment research was raised by Nate Soares:

I’ve historically been pretty publicly supportive of interpretability research. I’m still supportive of interpretability research. However, I do not necessarily think that all of it should be done in the open indefinitely. Indeed, insofar as interpretability researchers gain understanding of AIs that could significantly advance the capabilities frontier, I encourage interpretability researchers to keep their research closed.

Interpretability research is also warned about by Justin Shovelain and Elliot Mckernon of Convergence Analysis:

Here are some heuristics to consider if you’re involved or interested in interpretability research (in ascending order of nuance):

Research safer topics instead. There are many research areas in AI safety, and if you want to ensure your research is net positive, one way is to focus on areas without applications to AI capabilities.

Research safer sub-topics within interpretability. As we’ll discuss in the next section, some areas are riskier than others—changing your focus to a less risky area could ensure your research is net positive.

Conduct interpretability research cautiously, if you’re confident you can do interpretability research safely, with a net-positive effect. In this case:

Stay cautious and up to date. Familiarize yourself with the ways that interpretability research can enhance capabilities, and update and apply this knowledge to keep your research safe.

Advocate for caution publicly.

Carefully consider what information you share with whom. This particular topic is covered in detail in Should we publish mechanistic interpretability research?, but to summarise: it may be beneficial to conduct interpretability research and share it only with select individuals and groups, ensuring that any potential benefit to capability enhancement isn’t used for such.

General AI Withdrawal

It’s not just alignment and capability research you need to watch out for—anything connected to AI could conceivably advance timelines and therefore is inadvisable. Examples:

Again from Zvi’s “Practical Advice for the Worried”, mentioned above:

Q: How would you rate the ‘badness’ of doing the following actions: Direct work at major AI labs, working in VC funding AI companies, using applications based on the models, playing around and finding jailbreaks, things related to jobs or hobbies, doing menial tasks, having chats about the cool aspects of AI models?

A: Ask yourself what you think accelerates AI to what extent, and what improves our ability to align one to what extent. This is my personal take only – you should think about what your model says about the things you might do. So here goes. Working directly on AI capabilities, or working directly to fund work on AI capabilities, both seem maximally bad, with ‘which is worse’ being a question of scope. Working on the core capabilities of the LLMs seems worse than working on applications and layers, but applications and layers are how LLMs are going to get more funding and more capabilities work, so the more promising the applications and layers, the more I’d worry. Similarly, if you are spreading the hype about AI in ways that advance its use and drive more investment, that is not great, but seems hard to do that much on such fronts on the margin unless you are broadcasting in some fashion, and you would presumably also mention the risks at least somewhat.

So in addition to not working on capabilities, Zvi recommends not investing in organizations that use AI, and not working on applications of LLMs, with the note that doing things that build hype or publicity about AI is “not great” but isn’t that big a deal.

On the other hand, maybe publicity isn’t OK after all—in Hooray for stepping out of the limelight, Nate Soares comes out against publicity and hype:

From maybe 2013 to 2016, DeepMind was at the forefront of hype around AGI. Since then, they’ve done less hype. For example, AlphaStar was not hyped nearly as much as I think it could have been.

I think that there’s a very solid chance that this was an intentional move on the part of DeepMind: that they’ve been intentionally avoiding making AGI capabilities seem sexy.

In the wake of big public releases like ChatGPT and Sydney and GPT-4, I think it’s worth appreciating this move on DeepMind’s part. It’s not a very visible move. It’s easy to fail to notice. It probably hurts their own position in the arms race. I think it’s a prosocial move.

What is the cost of these withdrawals?

The Cost of Capabilities Withdrawal

Right now it seems likely that the first AGI and later ASI will be built with utmost caution by people who take AI risk very seriously. If voluntary withdrawal from capabilities is a success—if all of the people calling for OpenAI and DeepMind and Anthropic to shut down get their way—then this will not be the case.

But this is far from the only cost. Capabilities withdrawal also means that there will be less alignment research done. Capabilities organizations that are concerned about AI risk hire alignment researchers. Alignment research is already funding constrained—there are more qualified people who want to do alignment research than there are jobs available for them. As the number of available alignment jobs shrinks, the number of alignment researchers will shrink as well.

The alignment research that is done will be lower quality due to less access to compute, capability knowhow, and cutting edge AI systems. And, the research that does get done is far less likely to percolate through to researchers building cutting edge AI systems, because the people building those systems simply won’t be interested in reading it.

Lastly, capabilities withdrawal makes a government-implemented pause less likely, because the credibility of AI risk is closely tied to how many leading AI capability researchers take AI risk seriously. People in the alignment community are in a bubble, and talk about “alignment research” and “capability research” as if they are two distinct fields of approximately equal import. To everyone else, the field of “AI capability research” is just known as “AI research”. And so, by trying to remove people worried about AI risk from AI research, you are trying to bring about a scenario where the field of AI research has a consensus that AI risk is not a real problem. This will be utterly disastrous for efforts to get government regulations and interventions through.

Articles like this, this, and this:

are only possible because the people featured in them pushed AI capabilities.

Similarly, look at the top signatories of the CAIS Statement on AI Risk which had such a huge impact on the public profile of AI risk:

Why do you think they chose to lead off with these signatures and not Eliezer Yudkowsky’s? If the push for individual withdrawal from capabilities work is a success, then any time a government-implemented pause is proposed the expert consensus will be that no pause is necessary and AI does not represent an existential risk.

The Cost of Alignment Withdrawal

Capabilities withdrawal introduces a rift between the alignment community and the broader one of AI research. Alignment withdrawal will widen this rift as research is intentionally withheld from people working on cutting edge AI systems, for fear of advancing timelines.

A policy of not allowing people building powerful AI systems to see alignment research is a strong illustration of how AI risk has become a secondary concern to AI timelines.

The quality of alignment research that gets done will also drop, both because researchers will be restricting their research topics for fear of advancing capabilities, and because researchers won’t even be talking to each other freely.

Figuring out how to build an aligned general intelligence will necessarily involve knowing how to build a general intelligence at all. Because of this, promising alignment work will have implications for capabilities; trying to avoid alignment work that could speed up timelines will mean avoiding alignment work that might actually lead somewhere.

The Cost of General Withdrawal

As people worried about AI risk withdraw from fields tangentially related to AI capabilities—concerned VCs avoid funding AI companies, concerned software devs avoid developing apps or other technologies that use AI, and concerned internet denizens withdraw from miscellaneous communities like AI art—the presence of AI risk in all of these spaces will diminish. When the topic of AI risk comes up, all of these places—AI startups, AI apps, AI discord communities—will find fewer and fewer people willing to defend AI risk as a concern worth taking seriously. And, in the event that these areas have influence over how AI is deployed, when AI is deployed it will be done without thought given to potential risks.

Benefits

The benefit of withdrawal is not a pause or a stop. As long as there is no consensus on AI risk, individual withdrawal cannot lead to a stop. The benefit, then, is that AI is slowed down. By how much? This will depend on a lot of assumptions, and so I’ll leave it to the reader to make up their own mind. How much will all of the withdrawal going on—every young STEM nerd worried about AI risk who decides not to get a PhD in AI because they’d have to publish a paper and Zvi said that advancing capabilities is the worst thing you could do, every alignment researcher who doesn’t publish or who turns away from a promising line of research because they’re worried it would advance capabilities, every software engineer who doesn’t work on that cool AI app they had in mind—how much do you think all of this will slow down AI?

And, is that time worth the cost?

- The case for a negative alignment tax by (18 Sep 2024 18:33 UTC; 79 points)

- 's comment on Anthropic’s leading researchers acted as moderate accelerationists by (2 Sep 2025 13:36 UTC; 65 points)

- There Should Be More Alignment-Driven Startups by (31 May 2024 2:05 UTC; 62 points)

- There Should Be More Alignment-Driven Startups by (EA Forum; 31 May 2024 2:05 UTC; 30 points)

- AI Alignment [Incremental Progress Units] this Week (10/22/23) by (23 Oct 2023 20:32 UTC; 22 points)

I found the tone of this post annoying at times, especially for overgeneralizing (“the alignment community” is not monolithic) and exaggerating / mocking (e.g. the title). But I’m trying to look past that to the substance, of which there’s plenty :)

I think everyone agrees that you should weigh costs and benefits in any important decision. And everyone agrees that the costs and benefits may be different in different specific circumstances. At least, I sure hope everyone agrees with that! Also, everyone is in favor of accurate knowledge of costs and benefits. I will try to restate the points you’re making, without the sass. But these are my own opinions now. (These are all pro tanto, i.e. able to be outweighed by other considerations.)

If fewer people who care about AI risk join or found leading AI companies, then there will still be leading AI companies in the world, it’s just that a smaller fraction of their staff will care about AI risk than otherwise. (Cf. entryism.) (On the other hand, presumably those companies would make less progress on the margin.)

And one possible consequence of “smaller fraction of their staff will care about AI risk” is less hiring of alignment researchers into these companies. Insofar as working with cutting-edge models and knowhow is important for alignment research (a controversial topic, where I’m on the skeptical side), and insofar as philanthropists and others aren’t adequately funding alignment research (unfortunately true), then it’s especially great if these companies support lots of high-quality alignment research.

If fewer people who care about AI risk go about acquiring a reputation as a prestigious AI researcher, or acquiring AI credentials like PhDs then there will still be prestigious and credentialed AI researchers in the world, it’s just that a smaller fraction of them will care about AI risk than otherwise. (On the other hand, presumably those prestigious researchers would collectively make less progress on the margin.)

This and the previous bullet point are relevant to public perceptions, outreach, legislation efforts, etc.

MIRI has long kept some of their ideas secret, and at least some alignment people think that some MIRI people are “overly cautious with infosec”. Presumably at least some other people disagree, or they wouldn’t have that policy. I don’t know the secrets, so I am at a loss to figure out who’s in the right here. Incidentally, the OP implies that the stuff MIRI is choosing not to publish is “alignment research”, which I think is at least not obvious. One presumes that the ideas might bear on alignment research, or else they wouldn’t be thinking about it, but I think that’s a weaker statement, at least for the way I define “alignment research”.

If “the first AGI and later ASI will be built with utmost caution by people who take AI risk very seriously”, then that’s sure a whole lot better than the alternative, and probably necessary for survival, but experts strongly disagree about whether it’s sufficient for survival.

(The OP also suggests that this is the course we’re on. Well that depends on what “utmost caution” means. One can imagine companies being much less cautious than they have been so far, but also, one can imagine companies being much more cautious than they have been so far. E.g. I’d be very surprised if OpenAI etc. lives up to these standards, and forget about these standards. Regardless, we can all agree that more caution is better than less.)

A couple alignment people have commented that interpretability research can have problematic capabilities externalities, although neither was saying that all of it should halt right now or anything like that.

(For my part, I think interpretability researchers should weight costs and benefits of doing the research, and also the costs and benefits of publishing the results, on a case-by-case basis, just like everyone else should.)

The more that alignment researchers freely share information, the better and faster they will produce alignment research.

If alignment researchers are publishing some stuff, but not publishing other stuff, then that’s not necessarily good enough, because maybe the latter stuff is essential for alignment.

If fewer people who care about AI risk become VCs who invest in AI companies, or join AI startups or AI discord communities or whatever, then “the presence of AI risk in all of these spaces will diminish”.

I think some of these are more important and some are less, but all are real. I just think it’s extraordinarily important to be doing things on a case-by-case basis here. Like, let’s say I want to work at OpenAI, with the idea that I’m going to advocate for safety-promoting causes, and take actions that are minimally bad for timelines. OK, now I’ve been at OpenAI for a little while. How’s it going so far? What exactly am I working on? Am I actually advocating for the things I was hoping to advocate for? What are my prospects going forward? Am I being indoctrinated and socially pressured in ways that I don’t endorse? (Or am I indoctrinating and socially pressuring others? How?) Etc. Or: I’m a VC investing in AI companies. What’s the counterfactual if I wasn’t here? Do I actually have any influence over the companies I’m funding, and if so, what am I doing with that influence, now and in the future?

Anyway, one big thing that I see as missing from the post is the idea:

“X is an interesting AI idea, and it’s big if true, and more importantly, if it’s true, then people will necessarily discover X in the course of building AGI. OK, guess I won’t publish it. After all, if it’s true, then someone else will publish it sooner or later. And then—and only then—I can pick up this strand of research that depends on X and talk about it more freely. Meanwhile maybe I’ll keep thinking about it but not publish it.”

In those kinds of cases, not publishing is a clear win IMO. More discussion at “Endgame safety” for AGI. For my part, I say that kind of thing all the time.

And I publish some stuff where I think the benefits of publishing outweigh the costs, and don’t publish other stuff where I think they don’t, on a case-by-case basis, and it’s super annoying and stressful and I never know (and never will know) if I’m making the right decisions, but I think it’s far superior to blanket policies.

> I just think it’s extraordinarily important to be doing things on a case-by-case basis here. Like, let’s say I want to work at OpenAI, with the idea that I’m going to advocate for safety-promoting causes, and take actions that are minimally bad for timelines.

Notice that this is phrasing AI safety and AI timelines as two equal concerns that are worth trading off against each other. I don’t think they are equal, and I think most people would have far better impact if they completely struck “I’m worried this will advance timelines” from their thinking and instead focused solely on “how can I make AI risk better”.

I considered talking about why I think this is the case psychologically, but for the piece I felt it was more productive to focus on the object level arguments for why the tradeoffs people are making are bad. But to go into the psychological component a bit:

-Loss aversion: The fear of making AI risk worse is greater than the joy of making it better.

-Status quo bias: Doing something, especially something like working on AI capabilities, is seen as giving you responsibility for the problem. We see this with rhetoric against AGI labs—many in the alignment community will level terrible accusations against them, all while having to admit when pressed that it is plausible they are making AI risk better.

-Fear undermining probability estimates: I don’t know if there’s a catchy phrase for this one but I think it’s real. The impacts of any actions you take will be very muddy, indirect, and uncertain, because this is a big, long term problem. When you are afraid, this makes you view uncertain positive impacts with suspicion and makes you see uncertain negative impacts as more likely. So people doubt tenuous contributions to AI safety like “AI capability researchers worried about AI risk lend credibility to the problem, thereby making AI risk better”, but view tenuous contributions to AI risk like “you publish a capabilities paper, thereby speeding up timelines, making AI risk worse” as plausible.

This seems confused in many respects. AI safety is the thing I care about. I think AI timelines are a factor contributing to AI safety, via having more time to do AI safety technical research, and maybe also other things like getting better AI-related governance and institutions. You’re welcome to argue that shorter AI timelines other things equal do not make safe & beneficial AGI less likely—i.e., you can argue for: “Shortening AI timelines should be excluded from cost-benefit analysis because it is not a cost in the first place.” Some people believe that, although I happen to strongly disagree. Is that what you believe? If so, I’m confused. You should have just said it directly. It would make almost everything in this OP besides the point, right? I understood this OP to be taking the perspective that shortening AI timelines is bad, but the benefits of doing so greatly outweigh the costs, and the OP is mainly listing out various benefits of being willing to shorten timelines.

Putting that aside, “two equal concerns” is a strange phrasing. The whole idea of cost-benefit analysis is that the costs and benefits are generally not equal, and we’re trying to figure out which one is bigger (in the context of the decision in question).

If someone thinks that shortening AI timelines is bad, then I think they shouldn’t and won’t ignore that. If they estimate that, in a particular decision, they’re shortening AI timelines infinitesimally, in exchange for a much larger benefit, then they shouldn’t ignore that either. I think “shortening AI timelines is bad but you should completely ignore that fact in all your actions” is a really bad plan. Not all timeline-shortening actions have infinitesimal consequence, and not all associated safety benefits are much larger. In some cases it’s the other way around—massive timeline-shortening for infinitesimal benefit. You won’t know which it is in a particular circumstance if you declare a priori that you’re not going to think about it in the first place.

I think another “psychological” factor is a deontological / Hippocratic Oath / virtue kind of thing: “first, do no harm”. Somewhat relatedly, it can come across as hypocritical if someone is building AGI on weekdays and publicly advocating for everyone to stop building AGI on weekends. (I’m not agreeing or disagreeing with this paragraph, just stating an observation.)

I think you’re confused about the perspective that you’re trying to argue against. Lots of people are very confident, including “when pressed”, that we’d probably be in a much better place right now if the big AGI labs (especially OpenAI) had never been founded. You can disagree, but you shouldn’t put words in people’s mouths.

The focus of the piece is on the cost of various methods taken to slow down AI timelines, with the thesis being that across a wide variety of different beliefs about the merit of slowing down AI, these costs aren’t worth it. I don’t think it’s confused to be agnostic about the merits of slowing down AI when the tradeoffs being taken are this bad.

Views on the merit of slowing down AI will be highly variable from person to person and will depend on a lot of extremely difficult and debatable premises that are nevertheless easy to have an opinion on. There is a place for debating all of those various premises and trying to nail down what exactly the benefit is of slowing down AI; but there is also a place for saying “hey, stop getting pulled in by that bike-shed and notice how these tradeoffs being taken are not worth it given pretty much any view on the benefit of slowing down AI”.

> I think you’re confused about the perspective that you’re trying to argue against. Lots of people are very confident, including “when pressed”, that we’d probably be in a much better place right now if the big AGI labs (especially OpenAI) had never been founded. You can disagree, but you shouldn’t put words in people’s mouths.

I was speaking from experience, having seen this dynamic play out multiple times. But yes, I’m aware that others are extremely confident in all kinds of specific and shaky premises.

This seems at least somewhat backwards to me. I think the credibility of AI Risk is more closely tied to how many people not at leading AI capabilities labs, but still broadly seen as trustworthy and knowledgeable on the topic, take AI risk seriously. An AI alignment field where the vast majority of people talking about the topic have their paycheck depend on their parent company developing AGI looks much less trustworthy (and indeed, people like Stuart Russell and Yoshua Bengio gain a huge amount of credibility specifically from not being at top labs).

Yoshua, isn’t it?

Oops, fixed.

Capabilities withdrawal doesn’t just mean fewer people worried about AI risk at top labs—it also means fewer Stuart Russells and Yoshua Bengios. In fact, publishing AI research is seen as worse than working in a lab that keeps its work private.

Then I think you are arguing against a straw man. I don’t know anyone who argued against doing the kind of research or writing that seems to have been compelling to Stuart or Yoshua.

As far as I can tell Stuart read a bunch of Bostrom and Eliezer stuff almost a decade ago, and Yoshua did the same and also has a bunch of grad students that did very clearly safety research with little capability externalities.

I think we’re talking past each other a bit. I’m saying that people sympathetic to AI risk will be discouraged from publishing AI capability work, and publishing AI capability work is exactly why Stuart Russell and Yoshua Bengio have credibility. Because publishing AI capability work is so strongly discouraged, any new professors of AI will to some degree be selected for not caring about AI risk, which was not the case when Russell or Bengio entered the field.

I agree that this is a concern that hypothetically could make a difference, but as I said in my other comment, we are likely to alienate many of the best people by doing means-end-reasoning like this (including people like Stuart and Yoshua), and also, this seems like a very slow process that would take decades to have a large effect, and my timelines are not that long.

Seems like we mostly agree and our difference is based on timelines. I agree the effect is more of a long term one, although I wouldn’t say decades. OpenAI was founded in 2015 and raised the profile of AI risk in 2022, so in the counterfactual case where Sam Altman was dissuaded from founding OpenAI due to timeline concerns, AI risk would have much lower public credibility less than a decade.

Public recognition as a researcher does seem to favour longer periods of time though, the biggest names are all people who’ve been in the field multiple decades, so you have a point there.

Stuart and Yoshua seem to be welcomed into the field just fine, and their stature as respected people on the topic of existential risk seems to be in good shape, and I don’t expect that to change on the relevant timescales.

I think people talking openly about the danger and harm caused by developing cutting edge systems is exactly the kind of thing that made them engage with the field, and a field that didn’t straightforwardly recognize and try to hold the people who are causing the harm accountable would have been much less likely to get at least Stuart involved (I know less about Yoshua). Stuart himself is one of the people who is harshest about people doing dangerous research, and who is most strongly calling for pretty hard accountability.

Thanks for writing this piece; I think your argument is an interesting one.

One observation I’ve made is that MIRI, despite its first-mover advantage in AI safety, no longer leads the conversation in a substantial way. I do attribute this somewhat to their lack of significant publications in the AI field since the mid-2010s, and their diminished reputation within the field itself. I feel like this serves as one data point that supports your claim.

I feel like you’ve done a good job laying out potential failure modes of the current strategy, but it’s not a slam dunk (not that I think it was your intention to write a slam dunk as much as it was to inject additional nuance to the debate). So I want to ask, have you put any thought into what a more effective strategy for maximizing work on AI safety might be?

My specific view:

OpenAI’s approach seems most promising to me

Alignment work will look a lot like regular AI work; it is unlikely that someone trying to theorize about how to solve alignment, separate from any particular AI system that they are trying to align, will see success.

Takeoff speed is more important than timelines. The ideal scenario is one where compute is the bottleneck and we figure out how to build AGI well before we have enough compute to build it, because this allows us to experiment with subhuman AGI systems.

Slow takeoff is pretty likely. I think we’ll need a lot more compute than we have before we can train human-level AGI

I don’t think alignment will be that hard. A LLM trained to be agentic can easily be trained to be corrigible.

Because I don’t think alignment will be that hard, I think a lot of AI risk involves ASI being built without proper precautions. I think if teams are taking the proper precautions it will probably be fine. This is one more reason why I think individual withdrawal is such a terrible idea.

As an aside, my subjective impression is that Yann LeCun is correct when he says that worry about AI risk is a minority position among AI researchers. I think a lot of pushes for individual withdrawal implicitly assume that most AI researchers are worried about AI risk.

With that said, I’m not super confident in anything I said above. My lack of confidence goes both ways; maybe AI alignment isn’t a real problem and Yann LeCun is right, or maybe AI alignment is a much more difficult problem than I think and theoretical work independent from day-to-day AI research is necessary. That’s why on a meta level I think people should pursue different approaches that seem promising to them and contribute how they think they personally are suited to contribute. For some people that will be public advocacy, for some that will be theorizing about alignment, for some that will be working at AI labs. But working in AI capabilities absolutely seems strongly +EV to me, and so do all of the major AI labs (DM + OAI + Anthropic). Even giving a small likelihood to the contrary view (timelines are very fast, alignment is hard and unsolved) doesn’t change that—if anything, if I thought ASI was imminent I would be even more glad that the leading labs were all concerned about AI risk.

Do you understand the nature of consciousness? Do you know the nature of right and wrong? Do you know how an AI would be able to figure out these things? Do you think a superintelligent AI can be “aligned” without knowing these things?

I suspect that MIRI was prioritising alignment research over the communication of that research when they were optimistic about their alignment directions panning out. It feels like that was a reasonable bet to make, even though I do wish they’d communicated their perspective earlier (happily, they’ve been publishing a lot more recently).

So when are you planning on ceasing to define the alignment community in a way that excludes the people who do net-beneficial capabilities work?

We could take this logic further. Any participation in the global economy could conceivably be connected to AI. Therefore people concerned about AI x-risk should quit their jobs, stop using any services, learn to live off nature, and go live as hermits.

Of course, it’s possible that the local ecosystem may have a connection to the local economy and thus the global economy, so even living off nature may have some influence on AI. Learning to survive on pure sunlight may thus be a crucial alignment research priority.

I strongly agree with Steven Byrnes suggestion that we consider things on a case-by-case basis. I think it’s both clear that some people in the alignment community have already taken actions that have significantly shortened timelines and also that it’s possible to go too far. I suspect that the earlier someone is in their career, the less they need to worry about accidentally causing capability externalities lest they end up paralysed, but the further people go, the more careful they have to be.

Strong upvote, I think it’s very important to avoid being paralyzed in the way you describe (and will become increasingly important as AI becomes an increasing proportion of the economy).

Here’s a related shortform I wrote.

I am an engineer. That means, if I see a problem, I run towards the fire and try to figure out how to put it out, and then ensure it doesn’t start again. (Plus, for this particular fire, Mars probably isn’t far enough to run if you were going to try to run away from it.) The fire in AI is coming from scaling labs rapidly increasing capabilities, and the possibility they might continue to do so at a rate faster than alignment can keep up. All of the major labs are headed by people who appear, from their thoughtful public statements, to be aware of and fairly cautious about AI x-risk (admittedly less cautious than Eliezer Yudkowsky, but more so than, say, Yann LeCun, let alone Mark Andreesson) — to the point that they have gone to some lengths to get world governments to regulate their industry (not normal behavior for captains of industry, and the people dismissing this as “regulatory capture” haven’t explained why industry would go out of their way to get regulated in the first place: regulatory capture is process that gets attempted after a robust regulatory regime already exists).

I think there is a shortage of “what success looks like” stories on LW about solving alignment. We need to a) solve alignment (which is almost certainly easier with experimental access large amounts of compute and not-fully-aligned versions of frontier models than without these), b) get the solution adopted by all the frontier labs, and c) ensure that no-one else later builds an equally powerful unaligned model. I’m dubious that a) can be done by a small group of people in Berkeley or London carefully not talking to anyone else, but I’m very certain that b) and c) can’t.

I think this is treating expert consensus and credibility as more fixed / independent / inexorably derived from working for big AI labs or gaining status in academia than is actually the case.

If lots of bright individuals all decide it’s not a good idea to work on AI capabilities, that fact itself shifts what the expert consensus actually is.

Also, when someone chooses not to work on AI capabilities research, it’s not like they’re withdrawing from productive society as a whole—they’re often very bright and capable people who choose to dedicate themselves to other socially and economically valuable projects.

Sometimes these other projects are directly related to aspects of AI x-risk (governance, consensus-building, movement building, etc.); sometimes they are entirely unrelated (earning to give, founding a startup or a charitable endeavor in an unrelated field). There are lots of ways for smart, hard-working, principled individuals to do good and build legible status, credibility, and wealth for themselves outside of AI capabilities. By choosing to work on AI capabilities instead, less talent will go into these alternatives.

I think this is false, though it’s a crux in any case.

Capabilities withdrawal is good because we don’t need big models to do the best alignment work, because that is theoretical work! Theoretical breakthroughs can make empirical research more efficient. It’s OK to stop doing capabilities-promoting empirical alignment, and focus on theory for a while.

(The overall idea of “if all alignment-knowledgeable capabilities people withdraw, then all capabilities will be done by people who don’t know/care about alignment” is still debatable, but distinct. One possible solution: safety-promoting AGI labs stop their capabilities work, but continue to hire capabilities people, partly to prevent them from working elsewhere. This is complicated, but not central to my objection above.)

I see this asymmetry a lot and may write a post on it:

If theoretical researchers are wrong, but you do follow their caution anyway, then empirical alignment goes slower… and capabilities research slows down even more. If theoretical researchers are right, but you don’t follow their caution, you continue or speedup AI capabilities to do less-useful alignment work.

It seems fairly obvious and probably uncontentious that reading AI safety related literature (MIRI stuff, and even more broadly the sequences, HPMOR) is reasonably well correlated with holding an AI risk or doomer worldview, which leads to a strong selection effect as those people end up competing for a limited number (although less so now) of AI safety jobs rather than working in DL advancing timelines. Indeed that was EY et al’s goal!

On the other hand, deep reading of DL/neurosci is less correlated or perhaps anticorrelated with the high p(doom) worldview. Part of that naturally could be selection effect (on both sides), but I argue that instead a large chunk of the standard doom arguments appeal only to those lacking grounding in DL/neuroscience—knowledge which tends to lead to a more optimistic wordlview.

All that being said, from what I see the net contribution of AI safety researchers to DL capability / AGI timelines effectively rounds to zero. The most relevant border exception is perhaps some of the interpretability work having engineering utility, but even there doesn’t seem to have developed much earlier.

Which population are you evaluating this with respect to? If with the general population, it seems obviously false. If with those on LessWrong, I’m uncertain. If with other academics, probably false. If with other people who know anything about DL, probably weakly false, but I’d guess it looks more like people who know a moderate amount are less worried than those who know a bit, but also less worried than those who know a lot. But I’m also pretty uncertain about that.

For those in DL or neurosci outside of LW, high p(doom) seems more rare, from what I can gather. For some specific examples of the notable DL+neurosci people: Jeff Hawkins doesn’t think AGI/ASI poses much existential risk, Hassabis takes the risk seriously but his words/actions strongly imply[1] low p(doom). Carmack doesn’t seem very worried. Hinton doesn’t give a p estimate but from recent interviews I’d guess he’s anywhere between p(5) and p(50). Randall O’ Reilly’s paper on neurmorophic AGI safety is an example[2]: there is risk yes but those who generally believe we are getting neurmorphic AGI mostly aren’t nearly as worried as EY/doomers.

For the LW neurosci contingent the shard theory people like Q Pope aren’t nearly as worried and largely optimistic. I’m also in that contingent and put p(doom) at ~5% or so. I’m not sure what Bryne’s p(doom) is but I’d wager it’s less than 50%.

Like this interview for example.

link

50% seems pretty high to me, I thought you were trying to make a population level case that the more knowledge you have about deep learning, the lower your probability of doom is. Outside LessWrong, I think most surveys are against your position. Most outside the field don’t see it as a world-ending issue, and surveys often turn up an average of over 10% among experts that it ends up being a world-ending issue. Though the ones I know of mostly look at DL researchers, not neuroscientists. I don’t think any survey has been done about the topic within the LessWrong-o-sphere. I do not know people’s pdooms off the top of my head. Seems plausible.

Yes sort of but not exactly—deep knowledge of DL and neurosci in particular is somewhat insulating against many of the doom arguments. People outside the field are not relevant here, i’m only concerned with a fairly elite group who have somewhat rare knowledge. For example there are only a handful of people on LW who I would consider demonstrably well read in DL&neurosci and they mostly have lower p(doom) then EY/MIRI.

If you are referring to this survey: https://aiimpacts.org/2022-expert-survey-on-progress-in-ai/?ref=warpnews.org

The actual results are near the complete opposite of what you claim.

5% is near my p(doom) and that of Q Pope’s (who is a self proclaimed optimist). So the median DL respondent from their survey is an optimist, which proves my point.

Also only a small portion of those sent the survey actually responded, and only a small portion of those who responded − 162 individuals—actually answered the doom question. It seems extremely unlikely that responding to that question was correlated with optimism, so there is probably a large sample bias effect here.

I will note that I was correct in the number I gave. The mean is 14%, the median is 5%. Though I didn’t know the median was so low, so good piece of data to include. And your original claim was about the fraction of people with high pdoom, so the median seems more relevant.

Otherwise, good points. I guess I have more disagreements with the DL networks than I thought.

The LessWrong Review runs every year to select the posts that have most stood the test of time. This post is not yet eligible for review, but will be at the end of 2024. The top fifty or so posts are featured prominently on the site throughout the year.

Hopefully, the review is better than karma at judging enduring value. If we have accurate prediction markets on the review results, maybe we can have better incentives on LessWrong today. Will this post make the top fifty?

Thank you for writing this post. One thing that I would be interested in as a comparison is another field where there are competing ethical concerns over training and working in it. For example, if I am concerned about global warming but I work at Shell in order to internally advocate for faster build out of renewable energy generation, better ESG, etc. is that a net positive benefit compared to not working there at all?

I am personally sceptical of the ‘change the system from the inside’ approach, but I dont know of any strong evidence either way. In the climate change example though, a common criticism of this approach is that the fossil fuel organisations gain social license and capital to keep developing new projects because they are seen to fund carbon capture research, develop some renewable projects, and so on. It might be worth considering that AI organisations can use ostensibly well funded safety departments and the papers their researchers produce in the same sort of way without it actually addressing dangerous AI developments.

However though, I think you have made a strong case for not withdrawing alltogether, particularly with respect to alignment withdrawal.

We should not study alignment and interpretability because that improves AI capabilities = We should not build steering wheels and airbags because that improves car capabilities. Not a perfect metaphor of course, but it surmises how I feel.