Instead of technical research, more people should focus on buying time

This post is the first in a sequence of posts about AI strategy. In the next post, we’ll provide more examples of “buying time” interventions that we’re excited about.

We’re grateful to Ajeya Cotra, Daniel Kokotajlo, Ashwin Acharya, and Andrea Miotti for feedback on this post.

If anyone is interested in working on “buying time” interventions, feel free to reach out. (Note that Thomas has a list of technical projects with specifics about how to implement them. We also have a list of non-technical projects).

Summary

A few months ago, when we met technical people interested in reducing AI x-risk, we were nearly always encouraging them to try to solve what we see as the core challenges of the alignment problem (e.g., inner misalignment, corrigibility, interpretability that generalizes to advanced systems).

But we’ve changed our mind.

On the margin, we think more alignment researchers should work on “buying time” interventions instead of technical alignment research (or whatever else they were doing).

To state the claim another way: on the margin, more researchers should backchain from “how do I make AGI timelines longer, make AI labs more concerned about x-risk, and present AI labs with clear things to do to reduce x-risk”, instead of “how do I solve the technical alignment problem?”

Some “buying time” interventions involve performing research that makes AI safety arguments more concrete or grounds them in ML (e.g., writing papers like Goal misgeneralization in deep reinforcement learning and Alignment from a deep learning perspective & discussing these with members of labs).

Some “buying time” interventions involve outreach and engagement with capabilities researchers, leaders in AI labs, and (to a lesser extent) the broader ML community (e.g., giving a presentation to a leading AI lab about power-seeking and deception). We expect that successful outreach efforts will also involve understanding the cruxes/counterarguments of the relevant stakeholders, identifying limitations of existing arguments, and openly acknowledging when the AI safety community is wrong/confused/uncertain about certain points.

We are excited about “buying time” interventions for four main reasons:

Multiplier effects: Delaying timelines by 1 year gives the entire alignment community an extra year to solve the problem.

End time: Some buying time interventions give the community a year at the end, where we have the most knowledge about the problem, access to near-AGI systems, the largest community size, the broadest network across other influential actors, and the most credibility at labs. Buying end time also increases the amount of serial alignment research, which some believe to be the bottleneck. We discuss this more below.

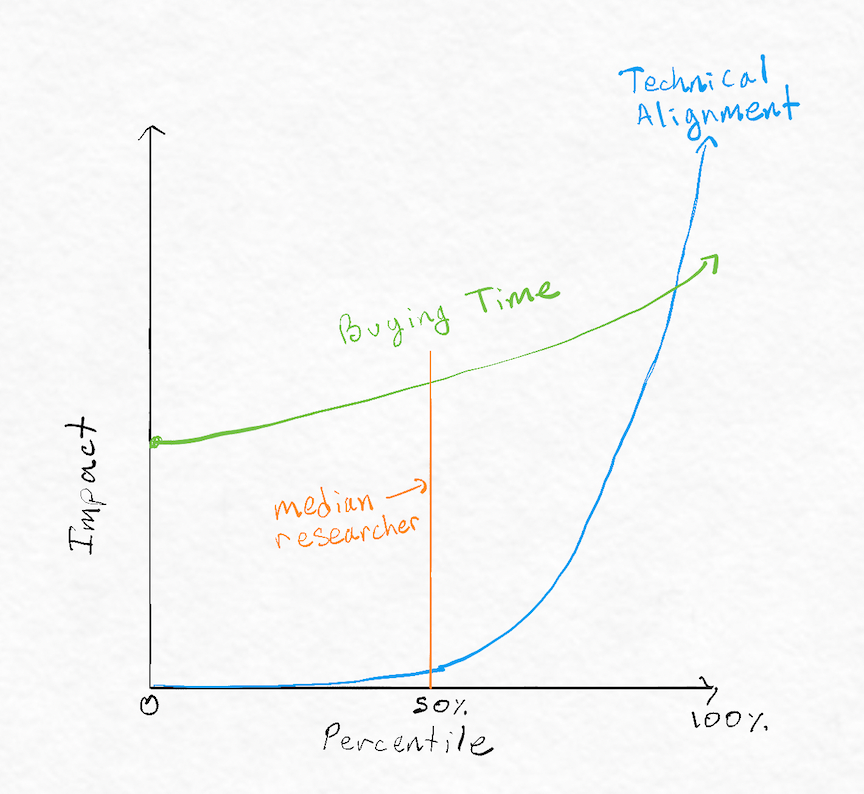

Comparative advantage: Many people would be better-suited for buying time than technical alignment work (see figure 1).

Buying time for people at the tails: We expect that alignment research is extremely heavy-tailed. A median researcher who decides to buy time is buying time for people at the tails, which is (much) more valuable than the median researcher’s time.

Externalities/extra benefits: Many buying time interventions have additional benefits (e.g., improving coordination, reducing race dynamics, increasing the willingness to pay a high alignment tax, getting more people working on alignment research).

Figure 1: Impact by percentile for technical alignment research and buying time interventions.

Caption: We believe that impact in technical alignment research is more heavy-tailed than impact for buying time interventions. Figure 1 illustrates this belief. Note that this is a rough approximation. Note also that both curves should also go below the 0-point of the y-axis, as both kinds of interventions can be net negative.

Concretely, we recommend that ~40-60% of alignment researchers should focus on “buying time” interventions rather than technical alignment research (whereas we currently think that only ~20% are focusing on buying time). We also recommend that ~20-40% of community-builders focus on “buying time” interventions rather than typical community-building (whereas we currently think that ~10% are focusing on buying time).

In the rest of the post, we:

Offer some disclaimers and caveats (here)

Elaborate on the reasons why we’re excited about “buying time” interventions (here)

Describe some examples of “buying time” interventions (here)

Explain our theory of change in greater detail (here)

Describe some potential objections & our responses (here)

Describe some changes we recommend (here)

Disclaimers

Disclaimer #1: We’re not claiming that “buying time” is the only way to categorize the kinds of interventions we describe, and we encourage readers to see if they can come up with alternative frames/labels. Many “buying time” interventions also have other benefits (e.g., improving coordination, getting more people to work on AI safety researchers, and making it less likely that labs deploy dangerous systems). We chose to go with the “buying time” frame for two main reasons

For nearly all of the interventions we describe, we think that most of the benefit comes from buying time, and these other benefits are side benefits. One important exception to this is that much of the impact of evals/demos may come from their ability to prevent labs from deploying dangerous systems. This buys time, but it’s plausible that the main benefit is “the world didn’t end”.

We have found backchaining from “buying time” more useful than other frames we brainstormed. Some alternative frames have felt too limiting (e.g., “outreach to the ML community” doesn’t cover some governance interventions).

Disclaimer #2: Many of these interventions have serious downside risks. We also think many of them are difficult, and they only have a shot at working if they are executed extremely well.

Disclaimer #3: We have several “background assumptions” that inform our thinking. Some examples include (a) somewhat short AI timelines (AGI likely developed in 5-15 years), (b) high alignment difficulty (alignment by default is unlikely, and current approaches seem unlikely to work), and (c) there has been some work done in each of these areas, but we are far behind what we would expect in winning worlds, and there are opportunities to do things that are much more targeted & ambitious than previous/existing projects.

Disclaimer #4: Much of our thinking is informed by conversations with technical AI safety researchers. We have less experience interacting with the governance community and even less experience thinking about interventions that involve the government. It’s possible that some of these ideas are already widespread among EAs who focus on governance interventions, and a lot of our arguments are directed at the thinking we see in the technical AI safety community.

Why are we so excited about “buying time” interventions?”

Large upsides of buying time

Some time-buying interventions buy a year at the end. If capabilities growth continues as normal until someone is about to deploy an AI model that would improve into a TAI, but an evaluation triggers and reveals misaligned behavior, causing this lab to slow down and warn the other labs, the time from this event until when AGI is deployed is very valuable for the following reasons:

You have bought one month for the entire AI safety community[1].

More researchers: The number of alignment researchers is growing each year, so we expect to have the most alignment researchers at the end.

Better understanding of alignment: We understand more about the alignment problem each year, and the field becomes less pre-paradigmatic. This makes it easier to make progress each year.

Serial time: buying time increases the amount of serial alignment research, which could be the bottleneck.

AGI assisted alignment: Some alignment agendas involve using AI assistants to boost alignment research. It’s plausible that a year of alignment research with AI assistants is 5-10X more valuable than a year of alignment research right now. If we’re able to implement interventions that buy time once we have powerful AI assistants, this intervention would be especially valuable (assuming that these assistants can make differential alignment progress or that we can buy time once we have the assistants).

Better understanding of architecture: when we are close to AGI, we have a better understanding of the architectures and training paradigms that will be used to actually build AGI, allowing for alignment solutions to be much more concrete and informed.

Other interventions have a different shape, and do not buy as valuable time. If you simply slow the rate of capabilities progress through publication policies or convince some capabilities researchers to transition, such that on net then AI will take one more year to generate, this has the benefit of 1-4, but not 5 and 6. However, we are proposing to reallocate alignment researchers to buying time interventions, which means that less alignment research is being made this year, so reason 3 might be less strong.

Some interventions that buy time involve coordinating with members of major AI labs (e.g., OpenAI, DeepMind, Anthropic). As a result, these interventions often have the additional benefit of increasing communication, coordination, trust, and shared understanding between major AI labs and members of the AI safety community who are not part of the AI labs. (Note that this is not true of all “buying time” interventions, and several of them could also lead to less coordination or less trust).

Tractability and comparative advantage: lots of people can have a solid positive impact by buying time, while fewer can do great alignment work

Buying a year buys a year for researchers at the tails. If you buy a year of time, you buy a year of time for some of the best alignment researchers. It’s plausible to us that researchers at the tails are >50-100X more valuable than median researchers.

Many projects that are designed to buy time require different skills than technical AI safety research.

Skills that seem uniquely valuable for buying time interventions: general researcher aptitudes, ability to take existing ideas and strengthen them, experimental design skills, ability to iterate in response to feedback, ability to build on the ideas of others, ability to draw connections between ideas, experience conducting “typical ML research,” strong models of ML/capabilities researchers, strong communication skills

Skills that seem uniquely valuable for technical AI safety research: abstract thinking, ability to work well with very little structure or guidance, ability to generate and formalize novel ideas, focus on “the hard parts of the problem”, ability to be comfortable being confused for long periods of time.

Skills that seem roughly as useful in both: Strong understanding of AI safety material, machine learning knowledge.

Alignment research seems heavy-tailed. It’s often easy to identify whether or not someone has a reasonable chance of being at the tail (e.g., after 6-12 months of trying to solve alignment). People who are somewhat likely to be at the tail should keep doing alignment research; other people should buy time.

A reasonable counterpoint is that “buying time” might also be heavily-tailed. However, we currently expect it to be less heavy-tailed than alignment research. It seems plausible to us that many “median SERI-MATS scholars” could write papers like the goal misgeneralization paper, explain alignment difficulties in clearer and more compelling ways, conduct (or organize) high-quality outreach and coordination activities and perform many other interventions we’re excited about. On the other hand, we don’t expect that “median SERI-MATS scholars” would be able to make progress on heuristic arguments, create their own alignment agendas, or come up with other major conceptual advancements.

Nonetheless, a lot of the argument depends on the specific time-buying and the specific alignment research. It seems plausible to us that some of the most difficult time-buying interventions are more heavy-tailed than some of the more straightforward alignment research projects (e.g., coming up with good eval tools and demos might be more heavy-tailed than performing interpretability experiments).

What are some examples of “buying time” interventions?

The next post in this sequence (rough draft here) outlines more concrete interventions that we are excited about in this space, but we highlight three interventions here that are especially exciting to us. We briefly provide some examples below.

Outreach efforts that involve interactions between the AI safety community and (a) members of AI labs + (b) members of the ML community.

Some specific examples:

More conferences that bring together researchers from different groups who are working on similar topics (e.g., Anthropic recently organized an interpretability retreat with members from various different AI labs and AI alignment organizations).

More conferences that bring together strategy/governance thinkers from different groups (e.g., Olivia and Akash recently ran a small 1-day strategy retreat with a few members from AI labs and members).

Discussions like the MIRI 2021 conversations, except with a greater emphasis on engaging with researchers and decision-makers at major AI labs by directly touching on their cruxes.

Collaborations on interventions that involve coordinating with AI labs (e.g., figuring out if there are ways to collaborate on research projects, efforts to implement publication policies and information-sharing agreements, efforts to monitor new actors that are developing AGI, etc.)

More ML community outreach. Examples include projects by the Center for AI Safety (led by Dan Hendrycks) and AIS field-building hub (led by Vael Gates).

The Evaluations Project (led by Beth Barnes)

Beth’s team is trying to develop evaluations that help us understand when AI models might be dangerous. The path to impact is that an AI company will likely use the eval tool on advanced AI models that they train, and this eval could then lead them to delay deployment of a model for which the eval unveiled scary behavior. In an ideal world, this would be so compelling that multiple AI labs slow down, potentially extending timelines by multiple years.

Papers that take theoretical/conceptual safety ideas and ground them in empirical research.

Specific examples of this type of work include Lauro Langosco’s goal misgeneralization paper (which shows how an RL agent can appear to learn goal X but actually learn goal Y) and Alex Turner’s optimal policies tend to seek power paper. Theoretical alignment researchers had already proposed that agents could learn unintended goals and that agents would have incentives to seek power. The papers by Lauro and Alex take these theoretical ideas (which are often perceived as fuzzy and lacking concreteness), formalize them more crisply, and offer examples of how they affect modern ML systems.

We think that this buys time primarily by convincing labs and academics of alignment difficulty. In the next section, we give more detail on the theory of chance.

Theory of Change

In the previous section, we talked about why we were so excited about buying time interventions. However, the interventions we have in mind often have a number of other positive impacts. In this section, we provide more detail about these impacts as well as why we think these impacts end up buying time.

We summarize our theory of change in the following diagram:

Labs take AGI x-risk seriously + Labs have concrete things they can do → More Time

We think that timelines are largely a function of (a) the extent to which leaders and researchers at AI labs are concerned about AI x-risk and (b) the extent to which they have solutions that can be (feasibly) implemented.

If conditions (a) and (b) are met, we expect the following benefits:

Less capabilities research. There is less scaling and less algorithmic progress.

More coordination between labs. There are more explicit and trusted agreements to help each other with safety research, avoid deploying AGI prematurely, and avoid racing.

Less publishing capabilities advances. Capabilities knowledge is siloed, so when one lab discovers something, it doesn’t get used by the rest of the world. For example, PaLM claims a 15% speed up from parallelizing layers. If this insight hadn’t been published, PaLM would likely have been 15% slower.

Labs being less likely to deploy AGI and scale existing models.

These all lead to relative slowdowns of AGI timelines, giving everyone more time to solve the alignment problem.

Benefits other than buying time

Many of the interventions we describe also have benefits other than buying time. We think the most important ones are:

Willingness to pay a higher alignment tax: Concern about alignment going poorly means that the labs invest more resources into safety. An obvious resource is that a computationally expensive solution to alignment becomes a lot more likely to be implemented, as the labs recognize how important it is. Concretely, we are substantially more excited about worlds in the lab building AGI actually implements all of the interventions described in Holden’s How might we align transformative AI if it’s developed very soon?. By default, if AGI were developed in the next few years at OpenAI or DeepMind, we would put ~20% on each of these solutions actually being used.

Less likely to deploy dangerous systems: If evaluations are used and safety standards are implemented, labs could catch misaligned behavior and decide not to deploy systems that would have ended the world. This leads to timelines increases, but it also has the more direct impact of literally saving the world (at least temporarily). We expect that this causes the probability of a naive accident risk to go down substantially.

More alignment research: If labs are convinced by AI safety arguments, they may shift more of their (capabilities) researchers toward alignment issues.

Some objections and our responses

1. There are downside risks from low-quality outreach and coordination efforts with AI labs

Response: We agree. Members of AI labs have their own opinions about AI safety; efforts to come in and proselytize are likely to fail. We think the best efforts will be conducted by people who have (a) strong understandings of technical AI safety arguments, (b) strong interpersonal skills and ability to understand different perspectives, (c) caution and good judgment, and (d) collaborators or advisors who can help them understand the space. However, this depends on the intervention. Caution is especially warranted when doing direct outreach that involves interaction with capabilities researchers, but more technical work such as empirically grounding alignment arguments pretty much only requires technical skill.

2. Labs perceive themselves to be in a race, so they won’t slow down.

Response #1: We think that some of the concrete interventions we have in mind contribute to coordination and reduce race dynamics. In particular, efforts to buy time by conveying the difficulty of alignment could lead multiple players to become more concerned about x-risk (causing all of the leading labs to slow down).

Furthermore, we’re optimistic that sufficiently well-executed coordination events could lead to increased trust and potentially concrete agreements between labs. We think that differences in values (company A is worried that company B would not use AI responsibly) and worries about misuse risk (company A is worried that company B’s AI is likely to be unaligned) are two primary drivers of race dynamics.

However, to the extent that A and B are value-aligned, both are aware that each of them are taking reasonable safety precautions, and leaders at both companies trust each other, they are less incentivized to race each other. Coordination events could help with each of these factors.

Response #2: Some interventions don’t reduce race dynamics (e.g., slowing down the leading lab). These are high EV in worlds where the safety-conscious lab (or labs) has a sizable advantage. On the margin, we think more people should be investing into these interventions, but they should be deployed more carefully (ideally after some research has been conducted to compare the upside of buying time to the downside of increasing race dynamics).

3. Labs being more concerned about safety isn’t that helpful. They already care; they just lack solutions.

Response: Our current impression is that many leaders at major AGI labs are concerned about safety. However, we don’t think everyone is safety-conscious, and we think there are some policies that labs could adopt to buy time (e.g., adopting publication policies that reduce the rate of capabilities papers).

4. Slowing down ODA+[2] could increase the chance that a new (and less safety-conscious actor) develops AGI.

Response #1: Our current best guess is that ODA+ has a >6 month lead over less safety-conscious competitors. However, this is fairly sensitive to timelines. If scale is critical, then one would expect a small number of very large projects to be in the lead for AGI, and differentially slowing the most receptive / safety oriented / cautious of those labs seems on net negative. However, interventions that slow the whole field such as a blanket slowdown in publishing or increases the extent to which all labs are safety oriented are robustly good.

Response #2: Even if ODA+ does not have a major lead, many of the interventions (like third-party audits) could scale to new AGI developers too. For example, if there’s a culture in the field of doing audits, and pressure to do so, talented researchers are likely not to want to work for you unless you participate, or if later there’s a regulatory regime attached to all that.

Response #3: Some interventions to buy time increase lead time of labs and slow research overall (e.g., making it more difficult for new players to enter the space; compelling evals or concretizations of alignment difficulties could cause many labs to slow down).

Response #4: Under our current model, most P(doom) comes from not having a solution to the alignment problem. So we’re willing to trade some P(solution gets implemented) and some P(AGI is aligned to my values) in exchange for a higher P(we find a solution). However, we acknowledge that there is a genuine tradeoff here, and given the uncertainty of the situation, Thomas thinks that this is the strongest argument against buying time interventions.

5. Buying time is not tractable.

Response: This is possible, but we currently doubt it. There seems to be a bunch of stuff that no one has tried (we will describe this further in a follow-up post).

6. In general, problems get solved by people actually trying to solve them. Not by avoiding the hard problems and hoping that people solve them in the future.

Response #1: Getting mainstream ML on board with alignment concerns is solving one of the hardest problems for the alignment field.

Response #2: Although some of the benefit from “buying time” involves hoping that new researchers show up with new ideas, we’re also buying time for existing researchers who are tackling the hard problems.

Response #3: People who have promising agendas that are attacking the core of the problem should continue doing technical alignment research. There are a lot of people who have been pushed to do technical alignment work who don’t have promising ideas (even after trying for years), or feel like they have gotten substantial signal that they are worse at thinking about alignment than others. These are the people we would be most excited to reallocate. (Note though that we think feedback loops in alignment are poor. Our current guess is that among the top 10% of junior researchers, it seems extremely hard to tell who will be in the tail. But it’s relatively easy to tell who is in the top 10-20% of junior researchers).

7. There’s a risk of overcorrection: maybe too many people will go into “buying time” interventions and too few people will go into technical alignment.

Response: Currently, we think that the AIS community heavily emphasizes the value of technical alignment relative to “buying time.” We think it’s unlikely that the culture shifts too far in the other direction.

8. This doesn’t seem truth-seeky or epistemically virtuous— trying to convince ML people of some specific claims feels wrong, especially given how confused we are and how much disagreement there is between alignment researchers.

Response #1: There are a core set of claims that are pretty well supported that the majority of the ML community has not substantially engaged with (e.g. goodharting, convergent instrumental goals, reward misspecification, goal misgeneralization, risks from power-seeking, risks from deception).

Response #2: We’re most excited about outreach efforts and coordination efforts that actually allow us to figure out how we’re wrong about things. If the alignment community is wrong about something, these interventions make it more likely that we find out (compared to a world in which we engage rather little with capabilities researchers + ML experts and only talk to people in our community). If others are able to refute or deconfuse points that are made in this outreach effort, this seems robustly good, and it seems possible that sufficiently good arguments would convince us (or the alignment community) about potentially cruxy issues.

What changes do we want to see?

Allocation of talent: On the margin, we think more people should be going into “buying time” interventions (and fewer people should be going into traditional safety research or traditional community-building).

Concretely, we think that roughly 80% of alignment researchers are working on directly solving alignment. We think that roughly 50% should be working on alignment, while 50% should be reallocated toward buying time.

We also think that roughly 90% of (competent) community-builders are focused on “typical community-building” (designed to get more alignment researchers). We think that roughly 70% should do typical community-building, and 30% should be buying time.

Culture: We think that “buying time” interventions should be thought of as a comparable or better path than (traditional) technical AI safety research and (traditional) community-building.

Funding: We’d be excited for funders to encourage more projects that buy time via ML outreach, improved coordination, taking conceptual ideas and grounding them empirically, etc.

Strategy: We’d be excited for more strategists to think concretely about what buying time looks like, how it could go wrong, and if/when it would make sense to accelerate capabilities (e.g., how would we know if OpenAI is about to lose to a less safety-conscious AI lab, and what would we want to do in this world?)

- ^

We did a BOTEC that suggested that 1 hour of alignment researcher time would buy, in expectation, 1.5-5 quality-adjusted research hours. The BOTEC made several conservative assumptions (e.g., it did not account for the fact that we expect alignment research to be more heavy-tailed than buying time interventions). We are in the process of revising our BOTEC, and we hope to post it once we have revised it.

- ^

ODA+ = OpenAI, DeepMind, Anthropic, and a small number of other actors.

- Cyborgism by (10 Feb 2023 14:47 UTC; 335 points)

- The Alignment Community Is Culturally Broken by (13 Nov 2022 18:53 UTC; 142 points)

- AI Summer Harvest by (4 Apr 2023 3:35 UTC; 130 points)

- Wentworth and Larsen on buying time by (9 Jan 2023 21:31 UTC; 74 points)

- An AI Race With China Can Be Better Than Not Racing by (2 Jul 2024 17:57 UTC; 68 points)

- 2022 (and All Time) Posts by Pingback Count by (16 Dec 2023 21:17 UTC; 53 points)

- Wentworth and Larsen on buying time by (EA Forum; 9 Jan 2023 21:31 UTC; 48 points)

- Ways to buy time by (EA Forum; 12 Nov 2022 19:31 UTC; 47 points)

- Slowing AI: Reading list by (17 Apr 2023 14:30 UTC; 47 points)

- List of requests for an AI slowdown/halt. by (14 Apr 2023 23:55 UTC; 46 points)

- For ELK truth is mostly a distraction by (4 Nov 2022 21:14 UTC; 44 points)

- Advice I found helpful in 2022 by (EA Forum; 28 Jan 2023 19:48 UTC; 40 points)

- List of projects that seem impactful for AI Governance by (EA Forum; 14 Jan 2024 16:52 UTC; 40 points)

- Advice I found helpful in 2022 by (28 Jan 2023 19:48 UTC; 36 points)

- Ways to buy time by (12 Nov 2022 19:31 UTC; 34 points)

- An AI Race With China Can Be Better Than Not Racing by (EA Forum; 2 Jul 2024 17:57 UTC; 19 points)

- List of projects that seem impactful for AI Governance by (14 Jan 2024 16:53 UTC; 14 points)

- Ideas for AI labs: Reading list by (24 Apr 2023 19:00 UTC; 11 points)

- Massive Scaling Should be Frowned Upon by (EA Forum; 17 Nov 2022 17:44 UTC; 9 points)

- 's comment on faul_sname’s Shortform by (18 Dec 2023 5:03 UTC; 6 points)

- Massive Scaling Should be Frowned Upon by (17 Nov 2022 8:43 UTC; 5 points)

- 's comment on An AI Race With China Can Be Better Than Not Racing by (3 Jul 2024 0:42 UTC; 4 points)

- 's comment on The Alignment Community Is Culturally Broken by (13 Nov 2022 23:50 UTC; 3 points)

- Why AI Safety is Hard by (22 Mar 2023 10:44 UTC; 1 point)

Epistemic status: Quick rant trying to get a bunch of intuitions and generators across, written in a very short time. Probably has some opinions expressed too strongly in various parts.

I appreciate seeing this post written, but currently think that if more people follow the advice in this post, this would make the world a lot worse (This is interesting because I personally think that at least for me, doing a bunch of “buying time” interventions are top candidates for what I think I should be doing with my life) I have a few different reasons for this:

I think organizing a group around political action is much more fraught than organizing a group around a set of shared epistemic virtues and confusions, and I expect a community that spent most of its time on something much closer to political advocacy would very quickly go insane. I think especially young people should really try to not spend their first few years after getting interested in the future of humanity going around and convincing others. I think that’s a terrible epistemic environment in which to engage honestly with the ideas.

I think the downside risk of most of these interventions is pretty huge, mostly because of effects on epistemics and morals (I don’t care that much about e.g. annoying capabilities researchers or something). I think a lot of these interventions have tempting paths where you exaggerate or lie or generally do things that are immoral in order to acquire political power, and I think this will both predictably cause a lot of high-integrity people to feel alienated and will cause the definitions and ontologies around AI alignment to get muddled, both within our own minds and the mind of the public.

Separately, many interventions in this space actually just make timelines shorter. I think sadly on the margin going around and trying to tell people about how dangerous and powerful AGI is going to be seems to mostly cause people to be even more interested in participating in its development, so that they can have a seat at the table when it comes to the discussion of “how to use this technology” (despite by far the biggest risk being accident risk, and it really not mattering very much for what ends we will try to use the technology)

I think making the world more broadly “safety concerned” does not actually help very much with causing people to go slower, or making saner decisions around AI. I think the dynamics here are extremely complicated and we have many examples of social movements and institutions that ended up achieving the opposite of their intended goals as the movement grew (e.g. environmentalists being the primary reason for the pushback against nuclear power).

The default of spreading vague “safety concern” memes is that people will start caring a lot about “who has control over the AI” and a lot of tribal infighting will happen, and decisions around AI will become worse. Nuclear power did not get safer when the world tried to regulate the hell out of how to design nuclear power plants (and in general the reliability literature suggests that trying to legislate reliability protocols does not work and is harmful). A world where the AIs are “legislated to be transparent” probably implies a world of less transparent AIs because the legislations for transparency will be crazy and dumb and not actually help much with understanding what is going on inside of your AIs.

Historically some strategies in this space have involved a lot of really talented people working at capabilities labs in order to “gain influence and trust”. I think the primary effect of this has also been to build AGI faster, with very limited success at actually getting these companies on a trajectory that will not have a very high chance of developing unaligned AI, or even getting any kind of long-term capital.

I think one of the primary effects of trying to do more outreach to ML-researchers has been a lot of people distorting the arguments in AI Alignment into a format that can somehow fit into ML papers and the existing ontology of ML researchers. I think this has somewhat reliably produced terrible papers with terrible pedagogy and has then caused many people to become actively confused about what actually makes AIs safe (with people walking away thinking that AI Alignment people want to teach AIs how to reproduce moral philosophy, or that OpenAIs large language model have been successfully “aligned”, or that we just need to throw some RLHF at the problem and the AI will learn our values fine). I am worried about seeing more of this, and I think this will overall make our job of actually getting humanity to sensibly relate to AI harder, not easier.

I think all of these problems can be overcome, and have been overcome by many people in the community, but I predict that the vast majority of efforts, especially by people who are not in the top percentiles of thinking about AI, and who avoided building detailed models of the space because they went into “buying time” interventions like the ones above, will result in making things worse in the way I listed above.

That said, I think I am actually excited about more people pursuing “buying time” interventions, but I don’t think trying to send the whole gigantic EA/longtermist community onto this task is going to be particularly fruitful. In contrast to your graph above, my graph for the payoff by percentile-of-talent for interventions in the space looks more like this:

My guess is maybe some people around the 70th percentile or so should work harder on buying us time, but I find myself very terrified of a 10,000 person community all somehow trying to pursue interventions like the ones you list above.

I appreciate this comment, because I think anyone who is trying to do these kinds of interventions needs to be constantly vigilant about exactly what you are mentioning. I am not excited about loads of inexperienced people suddenly trying to suddenly do big things in AI strategy, because downsides can be so high. Even people I trust are likely to make a lot of miscalculations. And the epistemics can be bad.

I wouldn’t be excited about (for example) retreats with undergrads to learn about “how you can help buy more time.” I’m not even sure of the sign of interventions people I trust pursue, let alone people with no experience who have barely thought about the problem. As somebody who is very inexperienced but interested in AI strategy, I will note that you do have to start somewhere to learn anything.

That said—and I don’t think you dispute this—we cannot afford to leave strategy/fieldbuilding/policy off the table. In my view, a huge part of making AI go well is going to depend on forces beyond the purely technical, but I understand that this varies depending on one’s threat models. Societechnical systems are very difficult to influence, and it’s easy to influence them in an incorrect direction. Not everyone should try to do this, and even people who are really smart and thinking clearly may have negative effects. But I think we still have to try.

I want to push back on your suggestion that safety culture is not relevant. I agree that being vaguely “concerned” does seem not very useful. But safety culture seems very important. Things like (paraphrased from this paper):

Preoccupation with failure, especially black swan events and unseen failures.

Reluctance to simplify interpretations and explain failures using only simplistic narratives.

Sensitivity to operations, which involves closely monitoring systems for unexpected behavior.

Commitment to resilience, which means being rapidly adaptable to change and willing to try new ideas when faced with unexpected circumstances.

Under-specification of organizational structures, where new information can travel throughout the entire organization rather than relying only on fixed reporting chains.

In my view, having this kind of culture (which is analagous to having a security mindset) proliferate would be a nearly unalloyed good. Notice there is nothing here that necessarily says “slow down”—one failure mode with telling the most safety conscious people to simply slow down is, of course, that less safety conscious people don’t. Rather, simply awareness and understanding, and taking safety seriously, I think is robustly positive regardless of the strategic situation. Doing as much as possible to extract out the old fashioned “move fast and break things” ethos and replace it with a safety-oriented ethos would be very helpful (though I will emphasize, will not solve everything).

Lastly, regarding this:

I’m curious if you think that these topics have no relevance to alignment, or whether you’re saying it’s problematic that people come away thinking that these things are the whole picture? Because I see all of these as relevant (to varying degrees), but certainly not sufficient or the whole picture.

Sorry, I don’t want to say that safety culture is not relevant, but I want to say something like… “the real safety culture is just ‘sanity’”.

Like, I think you are largely playing a losing game if you try to get people to care about “safety” if the people making decisions are incapably of considering long-chained arguments, or are in incentives structures that make it inherently difficult to consider new arguments, or like, belief that humanity cannot go extinct because that would go against the will of god.

Like, I think I am excited about people approaching the ML field with the perspective of “how can I make these people more sane, and help them see the effects of their actions more clearly”, and less excited about “how can I make people say that they support my efforts, give resources to my tribe, and say lots of applause lights that are associated with my ingroup”. I am quite worried we are doing a lot of the latter, and little of the former (I do think that we should also be a bit hesitant about the former, since marginal sanity might people mostly just better at making AGI, though I think the tradeoff is worth it). I think it’s actually really hard to have a community whose advocacy doesn’t primarily end up oriented around being self-recommending.

I think none of these topics have almost any relevance to AI Alignment. Like, I do want my AI in some sense to learn moral philosophy, but having it classify sentences as “utilitarian” or “deontological” feels completely useless to me. I also think OpenAIs large language model efforts have approximately nothing to do with actual alignment, and indeed I think are mostly doing the opposite of alignment (training systems to build human models, become agentic, and be incentivized towards deception, though I recognize this is not a consensus view in the AI Alignment field). The last one is just a common misunderstanding and like, a fine one to clear up, but of course I think if someone comes away from our materials believing that, then that’s pretty terrible since it will likely further emboldem them to mostly just run ahead with AI.

I think I essentially agree with respect to your definition of “sanity,” and that it should be a goal. For example, just getting people to think more about tail risk seems like your definition of “sanity” and my definition of “safety culture.” I agree that saying that they support my efforts and say applause lights is pretty bad, though it seems weird to me to discount actual resources coming in.

As for the last bit: trying to figure out the crux here. Are you just not very concerned about outer alignment/proxy gaming? I think if I was totally unconcerned about that, and only concerned with inner alignment/deception, I would think those areas were useless. As it is, I think a lot of the work is actively harmful (because it is mostly just advances capabilities) but it still may help chip away at the proxy gaming problem.

I think RLHF doesn’t make progress on outer alignment (like, it directly creates a reward for deceiving humans). I think the case for RLHF can’t route through solving outer alignment in the limit, but has to route through somehow making AIs more useful as supervisors or as researchers for solving the rest of the AI Alignment problem.

Like, I don’t see how RLHF “chips away at the proxy gaming problem”. In some sense it makes the problem much harder since you are directly pushing on deception as the limit to the proxy gaming problem, which is the worst case for the problem.

I’m not a big supporter of RLHF myself, but my steelman is something like:

RLHF is a pretty general framework for conforming a system to optimize for something that can’t clearly be defined. If we just did, “if a human looked at this for a second would they like it?” this does provide a reward signal towards deception, but also towards genuinely useful behavior. You can take steps to reduce the deception component, for example by letting the humans red team the model or do some kind of transparency; this can all theoretically fit in the framework of RLHF. One could try to make the human feedback as robust as possible by adding all sorts of bells and whistles, and this would improve reliability and reduce the deception reward signal. It could be argued this still isn’t sufficient because the model will still find some way around it, but beware too much asymptotic reasoning.

I personally do not find RLHF very appealing since I think it complexifies things unnecessarily and is too correlated with capabilities at the moment. I prefer approaches to actually try to isolate the things people actually care about (i.e. their values), add some level of uncertainty (moral uncertainty, etc.) to it, try to make these proxies as robust as possible, and make them adaptive to changes in the models that are trying to constantly exploit and Goodhart them.

This has also motivated me to post one of my favorite critiques of RLHF.

I worry that people will skip the post, read this comment, and misunderstand the post, so I want to point out how this comment might be misleading, even though it’s a great comment.

None of the interventions in the post are “go work at OpenAI to change things from the inside.” And only the outreach ones sound anything like “going around and convincing others.” And there’s a disclaimer that these interventions have serious downside risks and require extremely competent execution.

EDIT: one idea in the 2nd post is to join safety and governance teams at top labs like OpenAI. This seems reasonable to me? (“Go work on capabilities at OpenAI to change things” would sound unreasonable.)

I agree truth matters, but I have a question here: Why can’t we sacrifice a small amount of integrity and conventional morality in order to win political power, when the world is at stake? After all, we can resume it later, when the problem is solved.

As my favorite quote from Michael Vassar says: “First they came for our epistemology. And then they...well, we don’t really know what happened next”.

But some more detailed arguments:

In-particular if you believe in slow-takeoff worlds, a lot of the future of the world rests on our ability to stay sane when the world turns crazy. I think in most slow-takeoff worlds we are going to see a lot more things that make the world at least as crazy and tumultuous as during COVID, and I think our rationality was indeed not strong enough to really handle COVID gracefully (we successfully noticed it was happening before the rest of the world, but then fucked up by being locked down for far too long and too strictly when it was no longer worth it).

At the end of the day, you also just have to solve the AI Alignment problem, and I think that is the kind of problem where you should look very skeptically at trading off marginal sanity. I sure see a lot of people sliding off the problem and instead just rationalize doing capabilities research instead, which sure seems like a crazy error to me, but shows that even quite smart people with a bit less sanity are tempted to do pretty crazy things in this domain (or alternatively, if they are right, that a lot of the best things to do are really counterintuitive and require some galaxy-brain level thinking).

I think especially when you are getting involved in political domains and are sitting on billions of dollars of redirectable money and thousands of extremely bright redirectable young people, you will get a lot of people trying to redirect your resources towards their aims (or you yourself will feel the temptation that you can get a lot more resources for yourself if you just act a bit more adversarially). I think resistance against adversaries (at least for the kind of thing that we are trying to do) gets a lot worse if you lose marginal sanity. People can see each others reasoning being faulty, this reduces trust, which increases adversarialness, which reduces trust, etc.

And then there is also just the classical “Ghandi murder pill” argument where it sure seems that slightly less sane people care less about their sanity. I think the arguments for staying sane and honest and clear-viewed yourself are actually pretty subtle, and less sanity I think can easily send us off on a slope of trading away more sanity for more power. I think this is a pretty standard pathway that you can read about in lots of books and has happened in lots of institutions.

A few quick thoughts:

I think one of the foremost questions I and many people ask when deciding who to allocate political power to is “will this person abuse their position” (or relatedly “will the person follow-through on their stated principles when I cannot see their behavior”), and only secondarily “is this person the most competent for it or the most intelligent person with it”. Insofar as this is typical, in an iterated game you should act as someone who can be given political power without concern about whether you will abuse it, if you would like to be given it at all.

I tend to believe that, if I’m ever in a situation where I feel that I might want to trade ethics/integrity to get what I want, instead, if I am smarter or work harder for a few more months, I will be able to get it without making any such sacrifices, and this is better because ethical people with integrity will continue to trust and work with me.

A related way I think about this is that ethical people with integrity work together, but don’t want to work with people who don’t have ethics or integrity. For example I know someone who once deceived their manager, to get their job done (cf. Moral Mazes). Until I see this person repent or produce credible costly signals to the contrary, I will not give this person much resources or work with them.

That said ‘conventional’ ethics, i.e. the current conventions, include things like recycling and not asking people out on dates in the same company, and I already don’t think these are actually involved in ethical behavior, so I’ve no truck with dismissing those.

I don’t know who you have in your life, but in my life there is a marked difference between the people who clearly care about integrity, who clearly care about following the wishes of others when they have power over resources that they in some way owe to others, and those who do not (e.g. spending an hour thinking through the question “Hm, now that John let me stay at his house while he’s away, how would he want me to treat it?”). The cognition such people run would be quite costly to run differently at the specific time to notice that it’s worth it to take adversarial action, and they pay a heavy cost doing it in all the times I end up being able to check. The people whose word means something are clear to me, and my agreements with them are more forthcoming and simple than with others.

It is my experience that those with integrity are indeed not the sorts of people that people in corrupt organizations want to employ, they do not perform as the employers wish, and get caught up in internal conflicts.

I do have a difference in my mind between “People who I trust to be honest and follow through on commitments in the current, specific incentive landscape” and “People who I trust to be honest and follow through on commitments in a wide variety of incentive landscapes”.

Here is a sceptical take: anyone who is prone to getting convinced by this post to switch to attempts at “buying time” interventions from attempts at do technical AI safety is pretty likely not a good fit to try any high-powered buying-time interventions.

The whole thing reads a bit like “AI governance” and “AI strategy” reinvented under a different name, seemingly without bothering to understand what’s the current understanding.

Figuring out that AI strategy and governance are maybe important, in late 2022, after spending substantial time on AI safety, does not seem to be what I would expect from promising AI strategists. Apparent lack of coordination with people already working in this area does not seem like a promising sign from people who would like to engage with hard coordination problems.

Also, I’m worried about suggestions like

Concretely, we think that roughly 80% of alignment researchers are working on directly solving alignment. We think that roughly 50% should be working on alignment, while 50% should be reallocated toward buying time.

We also think that roughly 90% of (competent) community-builders are focused on “typical community-building” (designed to get more alignment researchers). We think that roughly 70% should do typical community-building, and 30% should be buying time.

...could be easily counterproductive.

What is and would be really valuable are people who understand both the so-called “technical problem” and the so-called “strategy problem”. (secretly, they have more in common than people think)

What is not only not valuable, but easily harmful, would be an influx of people who understand neither, but engage with the strategy domain instead of technical domain.

I overall agree with this comment, but do want to push back on this sentence. I don’t really know what it means to “invent AI governance” or “invent AI strategy”, so I don’t really know what it means to “reinvent AI governance” or “reinvent AI strategy”.

Separately, I also don’t really think it’s worth spending a ton of time trying to really understand what current people think about AI governance. Like, I think we are mostly confused, it’s a very green-field situation, and it really doesn’t seem to me to be the case that you have to read the existing stuff to helpfully contribute. Also a really large fraction of the existing stuff is actually just political advocacy dressed up as inquiry, and I think many people are better off not reading it (like, the number of times I was confused about a point of some AI governance paper and the explanation turned out to be “yeah, the author didn’t really believe this, but saying it would aim their political goals of being taken more seriously, or gaining reputation, or allowing them to later change policy in some different way” is substantially larger than the number of times I learned something helpful from these papers, so I do mostly recommend staying away from them).

By reinventing it, I means, for example, asking questions like “how to influence the dynamic between AI labs in a way which allows everyone to slow down at critical stage”, “can we convince some actors about AI risk without the main effect being they will put more resources into the race”, “what’s up with China”, “how to generally slow down things when necessary” and similar, and attempts to answer them.

I do agree that reading a lot of policy papers is of limited direct use in terms of direct hypothesis forming: in my experience the more valuable parts often have the form of private thoughts or semi-privately shared thinking.

On the other hand… in my view, if people have a decent epistemic base, they often should engage with the stuff you dislike, but from a proper perspective: not “this is the author attempting to literally communicate what they believe”, but more of “this is a written speech-act which probably makes some sense and has some purpose”. In other words… people who want to work on strategy unfortunately eventually need to be able to operate in epistemically hostile environments. They should train elsewhere, and spent enough time elsewhere to stay sane, but they need to understand e.g. how incentive landscapes influence what people think and write, and this is not possible to get good without dipping your feet in the water.

I’m sympathetic under some interpretations of “a ton of time,” but I think it’s still worth people’s time to spend at least ~10 hours of reading and ~10 hours of conversation getting caught up with AI governance/strategy thinking, if they want to contribute.

Arguments for this:

Some basic ideas/knowledge that the field is familiar with (e.g. on the semiconductor supply chain, antitrust law, immigration, US-China relations, how relevant governments and AI labs work, the history of international cooperation in the 20th century) seem really helpful for thinking about this stuff productively.

First-hand knowledge of how relevant governments and labs work is hard/costly to get on one’s own.

Lack of shared context makes collaboration with other researchers and funders more costly.

Even if the field doesn’t know that much and lots of papers are more advocacy pieces, people can learn from what the field does know and read the better content.

Yeah, totally, 10 hours of reading seems definitely worth it, and like, I think many hours of conversation, if only because those hours of conversation will probably just help you think through things yourself.

I also think it does make a decent amount of sense to coordinate with existing players in the field before launching new initiatives and doing big things, though I don’t think it should be a barrier before you suggest potential plans, or discuss potential directions forward.

Do you have links to stuff you think would be worthwhile for newcomers to read?

Yep! Here’s a compilation.

If someone’s been following along with popular LW posts on alignment and is new to governance, I’d expect them to find the “core readings” in “weeks” 4-6 most relevant.

Thanks!

I agree that “buying time” isn’t a very useful category. Some thoughts on the things which seem to fall under the “buying time” category:

Evaluations

I think people should mostly consider this as a subcategory of technical alignment work, in particular the work of understanding models. The best evaluations will include work that’s pretty continuous with ML research more generally, like fine-tuning on novel tasks, developing new prompting techniques, and application of interpretability techniques.

Governance work, some subcategories of which include:

Lab coordination: work on this should mainly be done in close consultation with people already working at big AI labs, in order to understand the relevant constraints and opportunities

Policy work: see standard resources on this

Various strands of technical work which is useful for the above

Outreach

One way to contribute to outreach is doing logistics for outreach programs (like the AGI safety fundamentals course)

Another way is to directly engage with ML researchers

Both of these seem very different from “buying time”—or at least “outreach to persuade people to become alignment researchers” doesn’t seem very different from “outreach to buy time somehow”

Thomas Kuhn argues in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions that research fields that focus directly on real-world fields usually make little progress. In his view, a field like physics where researchers in the 20th century focused on questions that are very theoretical produced a lot of progress.

When physicists work to advance the field of physics they look for possible experiments that can be done to increase the body of physics knowledge. A good portion of those doesn’t have any apparent real-world impact but they lead to accumulated knowledge in the field.

In contrast, a field like nutrition research tries to focus on questions that are directly relevant to how people eat. As a result, they don’t focus on fundamental research that leads to accumulated knowledge.

Given that background, I think that we want a good portion of alignment researchers not laser-focussed on specific theories of change.

I think that being driven by curiosity is different than being driven by a theory of change. Physicists are curious about figuring out any gaps in their models.

Feynman is also a good example. He hit a roadblock and couldn’t really think about how to work on any important problem so he decided to play around with math about physical problems.

If someone is curious to solve some problem in the broad sphere of alignment, it might be bad has to think about whether or not that actually helps with specific theories of change.

On the funding level, the theory of change might apply here, where you give the researchers who is able to solve some unsolved problem money because it progresses the field even if you have no idea whether the problem is useful to be solved. On the researcher level, it’s more being driven by curiosity.

At the same time, it’s also possible for the curiosity-driven approach to lead a field astray. Virology would be a good example. The virologists are curious about problems they can approach with the molecular biological toolkit but aren’t very curious about the problems you need to tackle to understand airborne transmission.

The virologists also do dangerous gain-of-function experiments that are driven by the curiosity to understand things about viruses but that are separate from a theory of change.

When approaching them a good stance might be: “If you do dangerous experiments then you need a theory of change” but for the non-dangerous experiments that are driven by curiosity to understand viruses without a theory of change there should be decent funding. You also want that there are some people who actually think about theory of change and go “If we want to prevent a pandemic, understanding how virus transmission works is important, so we should probably fund experiments for that even if it’s not the experiments toward which our curiosity drives us”.

Going back to the alignment question: You want to fund people who are curious about solving problems in the field to the extent that solving those problems isn’t likely to result in huge capability increases they should have decent funding. When it comes to working on problems where that are about capability increases you should require the researchers to have a clear theory of change. You also want some people to focus on a theory of change and seek problems based on a theory of change.

Thinking too hard about whether what you are doing actually is helping can lead to getting done nothing at all as Feymann experienced before we switched his approach.

It’s possible that at the present state of the AI safety field there are no clear roads to victory. If that’s the case then you would want to grow the AI safety field by letting researchers grow it more via curiosity-driven research.

The number of available researchers doesn’t tell you what’s actually required to make progress.

I feel somewhat conflicted about this post. I think a lot of the points are essentially true. For instance, I think it would be good if timelines could be longer all else equal. I also would love more coordination between AI labs. I also would like more people in AI labs to start paying attention to AI safety.

But I don’t really like the bottom line. The point of all of the above is not reducible to just “getting more time for the problem to be solved.”

First of all, the framing of “solving the problem” is, in my view, misplaced. Unless you think we will someday have a proof of beneficial AI (I think that’s highly unlikely), then there will always be more to do to increase certainty and reliability. There isn’t a moment when the problem is solved.

Second, these interventions are presented as a way of giving “alignment researchers” more time to make technical progress. But in my view, things like more coordination could lead to labs actually adopting any alignment proposals at all. The same is the case for racing. In terms of concern about AI safety, I’d expect labs would actually devote resources to this themselves if they are concerned. This shouldn’t be a side benefit, it should be a mainline benefit.

I don’t think high levels of reliability of beneficial AI will come purely from people who post on LessWrong, because the community is just so small and doesn’t have that much capital behind it. DeepMind/OpenAI, not to mention Google Brain and Meta AI research, could invest significantly more in safety than they do. So could governments (yes, the way they do this might be bad—but it could in principle be good).

You say that you thought buying time was the most important frame you found to backchain with. To me this illustrates a problem with backchaining. Dan Hendrycks and I discussed similar kinds of interventions, and we called this “improving contributing factors” which is what it’s called in complex systems theory. In my view, it’s a much better and less reductive frame for thinking about these kinds of interventions.

I’m confused why this is an objection. I agree that the authors should be specific about what it means to “solve the problem,” but all they need is a definition like “<10% chance of AI killing >1 billion people within 5 years of the development of AGI.”

I think if they operationalized it like that, fine, but I would find the frame “solving the problem” to be a very weird way of referring to that. Usually, when I hear people saying “solving the problem” they have a vague sense of what they are meaning, and have implicitly abstracted away the fact that there are many continuous problems where progress needs to be made and that the problem can only really be reduced, but never solved, unless there is actually a mathematical proof.

Thanks for posting this!

There’s a lot here I agree with (which might not be a surprise). Since the example interventions are all/mostly technical research or outreach to technical researchers, I’d add that a bunch of more “governance-flavored” interventions would also potentially contribute.

One of the main things that might keep AI companies from coordinating on safety is that some forms of coordination—especially more ambitious coordination—could violate antitrust law.

One thing that could help would be updating antitrust law or how it’s enforced so that it doesn’t do a terrible job at balancing anticompetition and safety concerns.

Another thing that could help would be a standard-setting organization, since coordination on standards is often more accepted when it’s done in such a context.

[Added] Can standards be helpful for safety before we have reliably safety methods? I think so; until then, we could imagine standards on things like what types of training runs to not run, or when to stop a training run.

If some leading AI lab (say, Google Brain) shows itself to be unreceptive to safety outreach and coordination efforts, and if the lead that more safety-conscious labs have over this lab is insufficient, then government action might be necessary to make sure that safety-conscious efforts have the time they need.

To be more direct, I’m nervous that people will (continue to) overlook a promising class of time-buying interventions (government-related ones) through mostly just having learned about government from information sources (e.g. popular news) that are too coarse and unrepresentative to make promising government interventions salient. Some people respond that getting governments to do useful things is clearly too intractable. But I don’t see how they can justifiably be so confident if they haven’t taken the time to form good models of government. At minimum, the US government seems clearly powerful enough (~$1.5 trillion discretionary annual budget, allied with nearly all developed countries, thousands of nukes, biggest military, experienced global spy network, hosts ODA+, etc.) for its interventions to be worth serious consideration.

(Update: I’m less optimistic about this than I was when I wrote this comment, but I still think it seems promising.)

This is the most and fastest I’ve updated on a single sentence as far back as I can remember. I am deeply gratefwl for learning this, and it’s definitely worth Taking Seriously. Hoping to look into it in January unless stuff gets in the way.

Have other people written about this anywhere?

I have one objection to claim 3a, however: Buying-time interventions are plausibly more heavy-tailed than alignment research in some cases because 1) the bottleneck for buying time is social influence and 2) social influence follows a power law due to preferential attachment. Luckily, the traits that make for top alignment researchers have limited (but not insignificant) overlap with the traits that make for top social influencers. So I think top alignment researchers should still not switch in most cases on the margin.

Please check out my writeup from April! https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/juhMehg89FrLX9pTj/a-grand-strategy-to-recruit-ai-capabilities-researchers-into

I would not have made this update by reading your post, and I think you are saying very different things. The thing I updated on from this post wasn’t “let’s try to persuade AI people to do safety instead,” it was the following:

If I am capable of doing an average amount of alignment work ¯x per unit time, and I have n units of time available before the development of transformative AI, I will have contributed ¯x∗n work. But if I expect to delay transformative AI by m units of time if I focus on it, everyone will have that additional time to do alignment work, which means my impact is ¯x∗m∗p, where p is the number of people doing work. Naively then, if m∗p>n, I should be focusing on buying time.[1]

This assumes time-buying and direct alignment-work is independent, whereas I expect doing either will help with the other to some extent.

That’s totally fair!

The part of my post I meant to highlight was the last sentence: “To put it bluntly, we should—on all fronts—scale up efforts to recruit talented AI capabilities researchers into AI safety research, in order to slow down the former in comparison to the latter. ”

Perhaps I should have made this point front-and-center.

No, this isn’t the same. If you wish, you could try to restate what I think the main point of this post is, and I could say if I think that’s accurate. At the moment, it seems to me like you’re misunderstanding what this post is saying.

I think the point of Thomas, Akash, and Olivia’s post is that more people should focus on buying time, because solving the AI safety/alignment problem before capabilities increase to the point of AGI is important, and right now the latter is progressing much faster than the former.

See the first two paragraphs of my post, although I could have made its point and the implicit modeling assumptions more explicitly clear:

“AI capabilities research seems to be substantially outpacing AI safety research. It is most likely true that successfully solving the AI alignment problem before the successful development of AGI is critical for the continued survival and thriving of humanity.

Assuming that AI capabilities research continues to outpace AI safety research, the former will eventually result in the most negative externality in history: a significant risk of human extinction. Despite this, a free-rider problem causes AI capabilities research to myopically push forward, both because of market competition and great power competition (e.g., U.S. and China). AI capabilities research is thus analogous to the societal production and usage of fossil fuels, and AI safety research is analogous to green-energy research. We want to scale up and accelerate green-energy research as soon as possible, so that we can halt the negative externalities of fossil fuel use.”

If the “multiplier effects” framing helped you update, then that’s really great! (I also found this framing helpful when I wrote it in this summer at SERI MATS, in the Alignment Game Tree group exercise for John Wentworth’s stream.)

I do think that in order for the “multiplier effects” explanation to hold, it needs to slow down capabilities research relative to safety research. Doing the latter with maximum efficiency is the core phenomenon that proves the optimality of the proposed action, not the former.

That’s fair, but sorry[1] I misstated my intended question. I meant that I was under the impression that you didn’t understand the argument, not that you didn’t understand the action they advocated for.

I understand that your post and this post argue for actions that are similar in effect. And your post is definitely relevant to the question I asked in my first comment, so I appreciate you linking it.

Actually sorry. Asking someone a question that you don’t expect yourself or the person to benefit from is not nice, even if it was just due to careless phrasing. I just wasted your time.

I’m excited by many of the interventions you describe but largely for reasons other than buying time. I’d expect buying time to be quite hard, in so far as it requires coordinating to prevent many actors from stopping doing something they’re incentivized to do. Whereas since alignment research community is small, doubling it is relatively easy. However, it’s ultimately a point in favor of the interventions that they look promising under multiple worldviews, but it might lead me to prioritize within them differently to you.

One area I would push back on is the skills you describe as being valuable for “buying time” seem like a laundry list for success in research in general, especially empirical ML research:

It seems pretty bad for the people strongest at empirical ML research to stop doing alignment research. Even if we pessimistically assume that empirical research now is useless (which I’d strongly disagree with), surely we need excellent empirical ML researchers to actually implement the ideas you hope the people who can “generate and formalize novel ideas” come up with. There are a few aspects of this (like communication skills) that do seem to differentially point in favor of “buying time”, maybe have a shorter and more curated list in future?

Separately given your fairly expansive list of things that “buy time” I’d have estimated that close to 50% of the alignment community are already doing this—even if they believe their primary route to impact is more direct. For example, I think most people working on safety at AGI labs would count under your definition: they can help convince decision-makers in the lab not to deploy unsafe AI systems, buying us time. A lot of the work on safety benchmarks or empirical demonstrations of failure modes falls into this category as well. Personally I’m concerned people are falling into this category of work by default and that there’s too much of this, although I do think when done well it can be very powerful.

How do you account for the fact that the impact of a particular contribution to object-level alignment research can compound over time?

Let’s say I have a technical alignment idea now that is both hard to learn and very usefwl, such that every recipient of it does alignment research a little more efficiently. But it takes time before that idea disseminates across the community.

At first, only a few people bother to learn it sufficiently to understand that it’s valuable. But every person that does so adds to the total strength of the signal that tells the rest of the community that they should prioritise learning this.

Not sure if this is the right framework, but let’s say that researchers will only bother learning it if the strength of the signal hits their person-specific threshold for prioritising it.

Number of researchers are normally distributed (or something) over threshold height, and the strength of the signal starts out below the peak of the distribution.

Then (under some assumptions about the strength of individual signals and the distribution of threshold height), every learner that adds to the signal will, at first, attract more than one learner that adds to the signal, until the signal passes the peak of the distribution and the idea reaches satiation/fixation in the community.

If something like the above model is correct, then the impact of alignment research plausibly goes down over time.

But the same is true of a lot of time-buying work (like outreach). I don’t know how to balance this, but I am now a little more skeptical of the relative value of buying time.

Importantly, this is not the same as “outreach”. Strong technical alignment ideas are most likely incompatible with almost everyone outside the community, so the idea doesn’t increase the number of people working on alignment.

I’m excited to see the next post in this sequence. I think the main counterargument, as has been pointed out by Habryka, Kulveit, and others, is that the graph at the beginning is not at all representative of the downsides from poorly executed buying-time interventions. TAO note the potential for downsides, but it’s not clear how they think about the EV of buying-time interventions, given these downsides.

This post has the problem of trying to give advice to a broad audience; among readers of this post, some should be doing buying-time work, some should do alignment research, some should fill in support roles, and some should do less-direct things (e.g., building capacities so that you may be useful later, or earning to give; not a complete list of things people should be doing). I suspect most folks agree that [people trying to make AI go well] should be taking different approaches; duh, comparative advantage is a thing.

Given that people should be doing different things, attempts at community coordination should aim to be relatively specific about who should do what; I feel this post does not add useful insight on the question of who should be doing buying-time interventions. I agree with the post’s thrust that buying-time interventions is important[1] and that there should be more of it happening, but I think this contribution doesn’t do much on its own. TAO should try to build an understanding of why people with various skills should pursue particular paths. Pointing in the direction of “we think more people should be going into “buying time” interventions” is different from directing the right individual people in that direction, and broad pointing will plausibly lead to a misallocation here.

This all said, I’m excited about the rest of the sequence, which I hope will better flesh out these ideas, including discussion of who is a good fit for time-buying interventions (building on CAIS’s related thoughts, which I would link but temporarily can’t find). I think this post will fit well into a whole sequence, insofar as it makes the point that time-buying interventions are particularly impactful, and other posts can address these other key factors (what interventions, who’s a good fit, existing projects in the space, and more).

and the idea around buying end-time being particularly valuable is a useful contribution

If you look at past interventions like this, weighted by quality, to what extent were they due to ideas that came from technical alignment research? I suspect a lot, but could be convinced otherwise.

A concrete suggestion for a buying-time intervention is to develop plans and coordination mechanisms (e.g. assurance contracts) for major AI actors/labs to agree to pay a fixed percentage alignment tax (in terms of compute) conditional on other actors also paying that percentage. I think it’s highly unlikely that this is new to you, but didn’t want to bystander just in case.

A second point is that there is a limited number of supercomputers that are anywhere close to the capacity of top supercomputers. The #10 most powerfwl is 0.005% as powerfwl as the #1. So it could be worth looking into facilitating coordination between them.

Perhaps one major advantage of focusing on supercomputer coordination is that the people who can make the relevant decisions[1] may not actually have any financial incentives to participate in the race for new AI systems. They have financial incentives to let companies use their hardware to train AIs, naturally, but they could be financially indifferent to how those AIs are trained.