Researcher at MIRI

peterbarnett

Were current models (e.g., Opus 4.5) trained using this updated constitution?

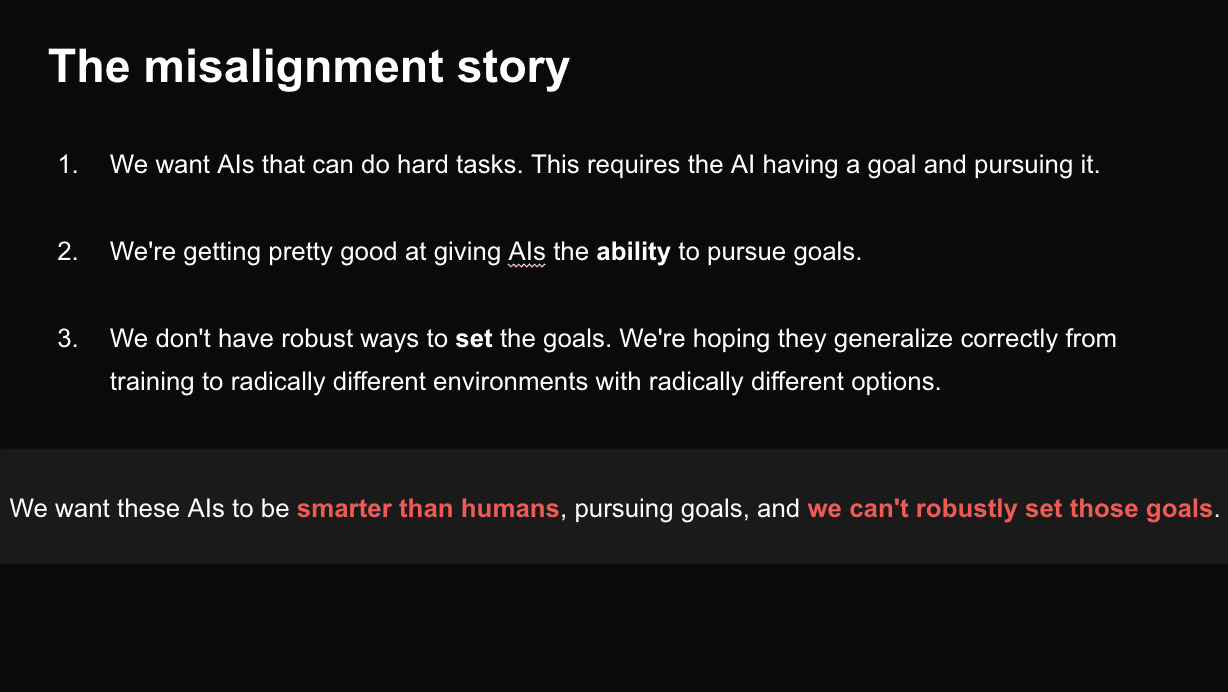

Here’s a slide from a talk I gave a couple of weeks ago. The point of the talk was “you should be concerned with the whole situation and the current plan is bad”, where AI takeover risk is just one part of this (IMO the biggest part). So this slide was my quickest way to describe the misalignment story, but I think there are a bunch of important subtleties that it doesn’t include.

Recognizable values are not the same as good values, but also I’m not at all convinced that the phenomena in this post will be impactful enough to outweigh all the somewhat random and contingent pressures what will shape a superintelligence’s values. I think a superintelligence’s values might be “recognizable” if we squint, and don’t look/think to hard, and if the superintelligence hasn’t had time to really reshape the universe.

Maybe I’m dense, but was the BART map the intended diagram?

The inability to copy/download is pretty weird. Anthropic seems to have deliberately disabled downloading, and rather than uploading a PDF, the webpage seems to be a bunch of PNG files.

I am very concerned about breakthroughs in continual/online/autonomous learning because this is obviously a necessary capability for an AI to be superhuman. At the same time, I think that this might make a bunch of alignment problems more obvious, as these problems only really arise when the AI is able to learn new things. This might result in a wake up of some AI researchers at least.

Or, this could just be wishful thinking, and continual learning might allow an AI to autonomously improve without human intervention and then kill everyone.

I like the sentiment and much of the advice in this post, but unfortunately I don’t think we can honestly confidently say “You will be OK”.

Announcing: MIRI Technical Governance Team Research Fellowship

Maybe useful to note that all the Google people on the “Chain of Thought Monitorability” paper are from Google Deepmind, while Hope and Titans are from Google Research.

Thanks!

Great point! This possibly makes my proposal a Bad idea. I would need to know more about how the labs respond to this kind of incentive to actually know.

Model providers often don’t provide the full CoT, and instead provide a summary. I think this is a fine/good thing to do to help prevent distillation.

However, I think it would be good if the summaries provided a flag for when the CoT contained evaluation awareness or scheming (or other potentially concerning behavior).

I worry that currently the summaries don’t really provide this information, and this probably makes alignment and capability evaluations less valid.

What they don’t do is filter out every web page that has the canary string. Since people put them on random web pages (like this one), which was not their intended use, they get into the training data.

As others have mentioned, this seems kinda crazy and bad. I was surprised you didn’t think this.

“Unrelated” question, but are you under a non-disparagement agreement with GDM that would prevent you from criticizing things like their data-filtering practices?

Considerations for setting the FLOP thresholds in our example international AI agreement

New Report: An International Agreement to Prevent the Premature Creation of Artificial Superintelligence

There’s a funny and bad incentive where I want to upvote posts I haven’t read to push them past the 30 Karma threshold and make them appear on the podcast feed.

I expect the line to blur between introspective and extrospective RSI. For example, you could imagine AIs trained for interp to doing interp on themselves, directly interpretting their own activations/internals and then making modifications while running.

Someone please explain

It might be good to have you talk about more research directions in AI safety you think are not worth pursuing or are over-invested in.

Also I think it would be good to talk about what the plan for automating AI alignment work would look like in practice (we’ve talked about this a little in person, but it would be good for it to be public).