Cultivating And Destroying Agency

Something that really surprised me about high school is how little agency the majority of the students there had. This was even more pronounced among the students at the local magnet school, Academies of Loudoun; they were selected for on intelligence and work ethic, but generally had a “the world affects me” mindset as opposed to “I affect the world”. It took me a while to understand what led to this, and over time my way of describing this went from “NPCs/sheeple (somewhat joking)” to “NPCs/sheeple (almost completely serious)” to my current way of describing it, which is “kids who had the agency burned out of them”.

In this post, I’ll go through the fully general way of increasing agency, some actual examples of that, and what it was that burned the agency out of my peers.

Building Agency

The academic term for agency, or the “I affect the world” vs. “The world affects me” continuum is internal vs. external locus of control, and I’ll be using that interchangeably with agency.

Charles Duhigg’s Smarter Faster Better has a chapter dedicated to locus of control. He talks about how the Marines restructured their basic training around building an internal locus of control:

Krulak [The head of the Marines] believed basic training needed to change. “We were seeing much weaker applicants,” he told me. “A lot of these kids didn’t just need discipline, they needed a mental makeover. They’d never belonged to a sports team, they’d never had a real job, they’d never done anything. They didn’t even have the vocabulary for ambition. They’d followed instructions their whole life.”

(...)

This was a problem, because the Corps increasingly needed troops who could make independent decisions… In today’s world, that means the Corps requires men and women capable of fighting in places such as Somalia and Baghdad, where rules and tactics change unpredictably and marines often have to decide—on their own and in real time—the best course of action.

This is one of two times I’ve seen an organization explicitly try to maximize agency in its members; the second is the Atlas Fellowship.

Duhigg went on to explain what researchers had found to be the core of creating an internal locus of control; choice. Presenting people with a choice, as opposed to just picking something for them, gives them a feeling of power over the outcome, instead of someone else picking their path for them.

If [Krulak] could redesign basic training to force trainees to take control of their own choices, that impulse might become more automatic, he hoped. “Today we call it teaching ‘a bias towards action,’ ” Krulak told me. “The idea is that once recruits have taken control of a few situations, they start to learn how good it feels.”

Building agency is a feedback loop. When people are agentic and pursue their own goals as opposed to executing the default strategy (which I’ll talk about later), they will be more agentic in the future if what they’ve done works. In environments like Marine basic camp, the environment is shaped to reward agency and independence; that by itself goes a long way towards encouraging agency.

So, to train the exercise of choice in basic training, the Marines began to add open-ended tasks into training.

In his fourth week of training, for instance, Quintanilla’s platoon was told to clean the mess hall. The recruits had no idea how. They didn’t know where the cleaning supplies were located or how the industrial dishwasher worked. Lunch had just ended and they weren’t sure if they were supposed to wrap the leftovers or throw them away. Whenever someone approached a drill instructor for advice, all he received was a scowl. So the platoon started making choices. The potato salad got tossed, the leftover hamburgers went into the fridge, and the dishwasher was loaded with so much detergent that suds soon covered the floor. It took three and a half hours, including the time sent mopping up the bubbles, for the platoon to finish cleaning the mess hall. They mistakenly threw away edible food accidentally turned off the ice cream freezer, and somehow managed to misplace two dozen forks. When they were done, however, their drill instructor approached the smallest, shyest member of the platoon and said he had noticed how the recruit had asserted himself when a decision was needed on where to put the ketchup. In truth, it was pretty obvious where the ketchup should have gone. There was a huge set of shelves containing nothing but ketchup bottles. But the shy recruit beamed as he was pleased.

The other challenge mentioned:

Midway through the Crucible, the recruits encountered a task called Sergeant Timmerman’s Tank. “The enemy has chemically contaminated this area,” a drill instructor shouted, pointing to a pit the size of a football field. “You must cross it while wearing full gear and gas masks. If a recruit touches the ground, you have failed and must start over. If you spend longer than sixty minutes in the pit, you have failed and must start over. You must obey your team leader. I repeat: You may not proceed without a direct verbal order from the team leader. You must hear a command before you act, otherwise you have failed and must start over.

Quintanilla’s team formed a circle and began using a technique they had learned in basic training.

“What’s our objective?” one recruit said.

“To cross the pit,” someone replied.

“How do we use the boards?” another recruit said, pointing to planks with ropes attached.

“We could lay them end to end,” someone answered. The team leader issued a verbal order and the circle broke up to test this idea along the border of the pit. They stood on one board while hauling the other forward. No one could keep their balance. The circle reformed. “How do we use the ropes? a recruit asked.

“To lift the planks,” another said. He suggested standing on both boards simultaneously and using the ropes to lift each piece in tandem, as if on skis.

The Marines complement those [psychological] insights by helping us understand how to teach drive to people who aren’t practiced in self-determination: If you give people an opportunity to feel a sense of control and let them practice making choices, they can learn to exert willpower. Once people know how to make self-directed choices into a habit, motivation becomes more automatic.

Moreover, to teach ourselves to self-motivate more easily, we need to learn to see our choices not just as expressions of control but also as affirmations of our values and goals. That’s the reason recruits ask each other “why”—because it shows them how to link small tasks to larger aspirations.

Nysmith Electives

My middle school, Nysmith, did an amazing job of having these open-ended challenges. The most notable were from my two eighth grade electives: Maker Lab and How To Make Or Break An Empire.

Maker Lab’s final project was multi-step.

We each came up with something we wanted to build in the class. Mine was a trebuchet; I remember my friend’s pick was little houses for bats.

Everyone gave a presentation on their idea to the class.

We voted on our favorite build ideas; the most popular, which in our class was just “build a cart”, would then be built by the class.

Individually create a custom design w/ blueprints for how you’d build the cart, using the CAD program Autodesk Inventor.

Break into groups of four, and then actually build the cart, with access to the many power tools and spare materials that our teacher had lying around.

Here’s what my group made:

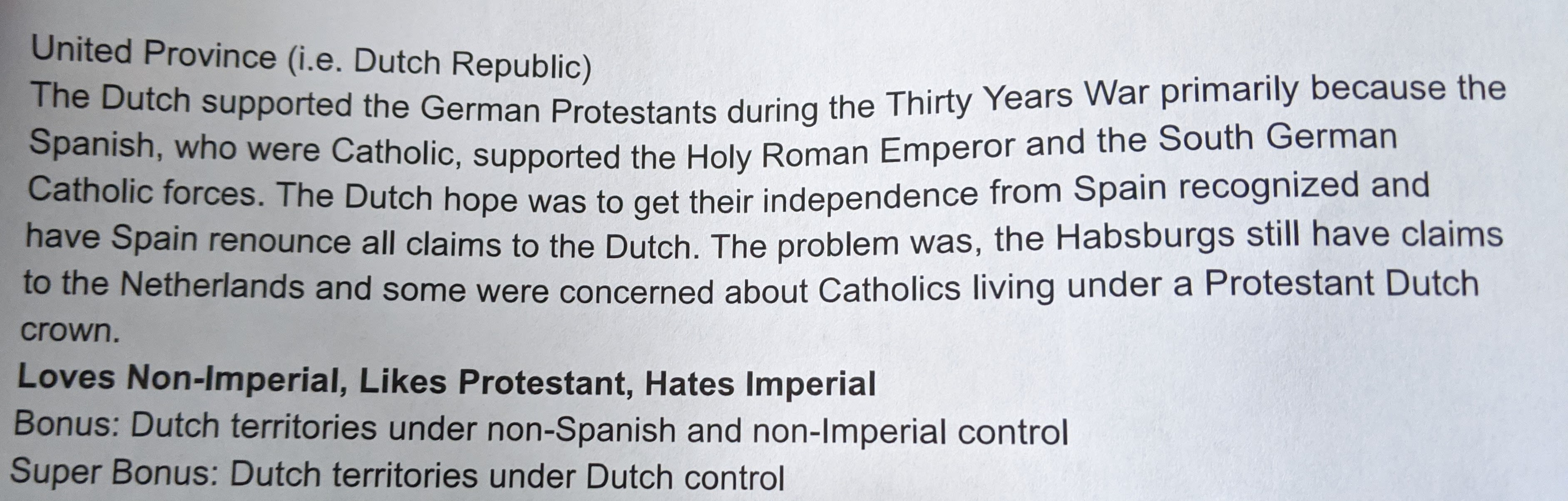

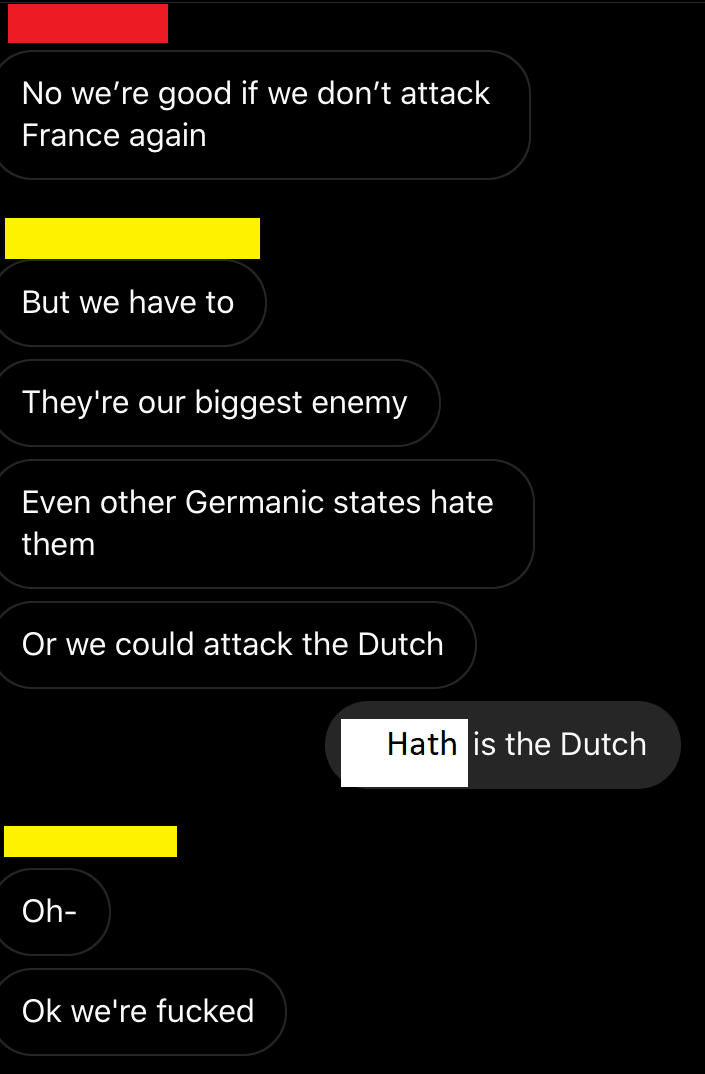

For Make Or Break An Empire, our final project was a detailed wargame of the Thirty Year’s War.

These were activities that had:

Little to no adult direction/instruction

Extremely high quality ceilings

Clear measures of success that weren’t “please the teacher to get a good grade”

Required initiative and the ability to work with other people for greater odds of success.

All of that forces kids to actually figure out how to complete difficult, open-ended tasks on their own. Some other high-agency, low-direction projects at Nysmith:

A grade-wide mock trial of Frankenstein’s monster, after reading the book

The science assignment to build a large Rube Goldberg machine, for which we were allowed to have incendiary components

The only things I’ve seen in all of my time at high school that’s anywhere near as good as Nysmith projects at teaching agency are AP Seminar, which is still significantly more constrained, formulaic, and boring, and the version of The Darwin Game that I helped run for our AP Computer Science class.

Personal activities

For something to increase your agency, it must require agency and succeed. For me, those were things like:

Signing up to take the AP BC Calculus exam two years ahead of schedule, and teaching myself the material

That Time I Almost Snuck Into Homecoming

Buying Visa gift cards for making online purchases

Asking people out, and generally being socially agentic (which Evie Cottrell describes well here)

Putting my own money into stocks, and getting 15x returns during the whole Gamestop thing.

For you, this should be things in your general area of expertise, but outside your social/societal comfort zone. Ideally, it would violate at least one social/institutional norm.

What’s with the kids?

Agentic people optimize for themselves; they think about what it is in life they want, and they do what it takes to get it.

That doesn’t work when you have, in the worst case, zero power whatsoever in your own life. This is the power that children have. Most of the time, this isn’t all bad; you just have “make sure my parents don’t get mad at me” permanently at the bottom rung of your hierarchy of needs. The worst case, however, is your parents forcing you to do exactly what they want you to do, in every situation, by punishing you for every single deviation from their norm.

Probably 60% of the students at Academies aren’t allowed to date. It’s easy for your parents to enforce that when they read through all of your texts, track your location with Life360, and don’t let you leave the house unsupervised. I have a friend who isn’t allowed to hang out with friends of the opposite sex. Her parents aren’t letting her go to college out of state, or so much as move out until she’s married. She can’t do anything to stop them; any fighting back will result in even worse conditions for her.

This is what I meant by “the kids in my high school have the agency burned out of them”. It’s an adaptive strategy, when the only thing that can bring you personal happiness is by pleasing your parents. Trying to learn to be agentic in their school with their parents is like trying to learn to be an independent thinker in 1984. Not a very conducive environment.

I’ve recently been reading a work of fiction that takes place in a dystopia where authorities punish infractions through literal torture. It’s somewhat counterproductive; when exposed to pain, people lose the ability to be creative and agentic, with all other thought processes replaced with MAKE IT STOP. This is what I’ve seen happen to my friends, to my peers, to people that could legitimately change the world if they were in a more competent situation. It breaks my heart.

School is a slightly easier environment to navigate, but is just as bad at producing agency. Something that helps is to see through the abstraction of “rules” and instead have a more specific model of actors and behaviors, like: “if I go to Ms. Nigro’s class during Advisory, she’ll report me to the front office, but if I instead spend my time in Ms. Novi’s classroom, nobody will be the wiser.” The Lesson To Unlearn, and the other recommendations in lsusr’s Advice For High School, are good at teaching you to think independently from The System.

One last thing.

My favorite section from Smarter Faster Better is this:

Researchers were studying why some seniors thrived inside such facilities, while others experienced rapid physical and mental declines. A critical difference, the researchers determined, was that the seniors who flourished made choices that rebelled against the rigid schedules, set menus, and strict rules that the nursing homes tried to force upon them.

Some researchers referred to such residents as “subversives,” because so many of their decisions manifested as small rebellions against the status quo. One group at a Santa Fe nursing home, for instance, started every meal by trading food items among themselves in order to construct meals of their own design rather than placidly accept what had been served to them. One resident told a researcher that he always gave his cake away because, even though he liked cake, he would “rather eat a second-class meal that I have chosen.”

A group of residents at a nursing home in Little Rock violated the institution’s rules by moving furniture around to personalize their bedrooms. Because wardrobes were attached to the walls, they used a crowbar—appropriated from a tool closet—to wrench their dressers free. In response, an administrator called a meeting and said there was no need to undertake independent redecorations; if the residents needed help, the staff would provide it. The residents informed the administrator that they didn’t want any assistance, didn’t need permission, and intended to continue doing whatever they damn well pleased.

These small acts of defiance were, in the grand scheme of things, relatively minor. But they were psychologically powerful because the subversives saw the rebellions as evidence that they were still in control of their own lives. The subversives walked, on average, about twice as much as other nursing home residents. They ate about a third more. They were better at complying with doctors’ orders, taking their medications, visiting the gym, and maintaining relationships with family and friends. These residents had arrived at the nursing homes with just as many health problems as their peers, but once inside, they lived longer,reported higher levels of happiness, and were far more active and intellectually engage.

“It’s the difference between making decision that prove to yourself that you’re still in charge of your life, versus falling into a mindset where you’re just waiting to die,” said Rosalie Kane, a gerontologist at the University of Minnesota. “It doesn’t really matter if you eat cake or not. But if you refuse to eat their cake, you’re demonstrating to yourself that you’re still in charge.” The subversives thrived because they knew how to take control, the same way that Quintanilla’s troop learned to cross a pit during the Crucible by deciding, on their own, how to interpret the rules [as was shown earlier in the chapter].

- Concrete examples of doing agentic things? by (12 Jan 2024 15:59 UTC; 13 points)

- London Rationalish meetup by (10 Sep 2022 11:18 UTC; 8 points)

- ACX Montreal meetup—July 5th @1PM by (2 Jul 2025 2:43 UTC; 5 points)

- 's comment on hath’s Shortform by (24 Feb 2023 2:21 UTC; 2 points)

- London Rationalish Meetup 2022-09-11 by (9 Sep 2022 18:39 UTC; 1 point)

I’m one of those people who’s never in my life been agentic. I still live in my parents’ house (I’m 25) and spend most of my time in my bedroom, because they burnt out all my capacity for agency when I was a child—it didn’t even take until teenage years. I can’t even go outside without telling someone!

Homeschooled till 16, never went to college because it seemed like a waste of money and anyway I was afraid of leaving the house, never had a job because I can’t stand the idea of yet another person telling me what to do and I don’t need anything that money could buy anyway, as long as I live here...

Endless free time, but no freedom, and no idea what I would do if I had freedom. It’s somehow hellish, comfortingly familiar, and completely emotionally neutral at the same time. Honestly, I feel totally trapped.

Sorry to complain lol. Point is, you’re right, this is a thing.

I’m really sorry to hear that, man. It’s honestly a horrible thing that this is what happens to so many people; it’s another sign of a generally inadequate civilization.

For what it’s worth, the first chapter of Smarter Faster Better is explicitly on motivation, and how to build it from nothing. It mentions multiple patients with brain injuries who were able to take back control over their own lives because someone else wanted to help them become agentic. I think reading that might help.

On another note, thank you for being open about this. I appreciate all comments on my posts, especially the ones actively related to the subject; your comment wasn’t complaining, and it was appreciated. Best of luck to you in the future.

Interesting, I’m homeschooled (unschooled specifically) and that probably benefited my agency (though I could still be much more agentic). I guess parenting styles matter a lot more then surface level “going to school”

You’re super brave for sharing this, it’s hard to stand up and say “Yes I’m the stereotypical example of the problem mentioned here”, stay optimistic though; people starting lower have risen higher.

My homeschooling was basically, my parents gave me textbooks and ignored me while I pretended to work through them and actually spent most of my time daydreaming because I hated the whole experience. Honestly the only reason I’m as smart as I am is that I’m naturally curious and they didn’t actively discourage that—they just didn’t encourage it particularly well either. I honestly have schooled myself more than anything—though nowhere near as well as I would like, as I lack motivation on my own and am at the mercy of my constantly changing interests.

My parents’ parenting style is essentially “children are extensions of their parents who must obey and never develop their own personality or opinions.” The fact that I’ve managed to do both of the latter things is again a testament to how hard it is to prevent, but I’m still regularly finding ways in which I have just passively assumed my parents were right about certain things without any evidence, and they in fact were wrong.

As for bravery: thank you, but I don’t have much filter, and I’m a bit self-centered. Talking about myself is usually easier than not doing so. :P

Related, copied from this FB post:

Accurate. My own aliveness was deadened for very pragmatic reasons; it’s what’s enabled me to endure my life. There are some advantages, such as greater rationality, but it was very eerie and disturbing noticing the capacity to feel strong emotions gradually weakening over the course of my teenage years. I don’t know if that will ever come back.

Overall I strongly agree with your post, but I’m confused about this example.

I don’t know all of the context of your friend’s situation, but you say “out of state” which makes me think that she lives in the US, in which case I don’t understand how her parents could prevent her from leaving home once she is an adult.

Are they...

Using emotional manipulation, e.g. making it clear that they’ll be really mad or disappointed if she doesn’t comply? In that case, that sounds like a toxic situation that your friend should leave.

Threatening to withhold funding and support that they would otherwise provide? This one is tough but it’s possible to go to college without being financially supported by your parents.

Physically preventing her from leaving? Less common but I’m sure it happens. They can’t legally do this, so at this point, if she is a legal adult, she could get police involved to escort her out out of the property.

It’s really hard to do from zero to living independently in one day. You need to save for a deposit, or have friends to crash with, a steady source of income, household management skills… Even going into a shelter requires knowing where it is and what the admission rules are.

It’s fairly easy for parents (or abusive spouses) to interrupt the process before your can actually leave. If they won’t fill out FAFSA good luck with college before age 25. They can emotionally punish going for job interviews. If you’re saving to leave but don’t have enough yet they can create an emergency and demand your savings. They can make demands on your schedule or disrupt your sleep so it’s impossible to work consistently.

And all of this can be wrapped in a bunch of physical and emotional abuse that makes everything much harder.

You can’t legally imprison an adult or keep them from leaving your home, but if you control their living situation and have for decades, there are a lot of morally awful but legally fine actions available to weaken your child and raise the difficulty of leaving.

Weird question but I am in the 2 situation. Is there any specific advice in terms of waying the loss vs gain in that situation. Edit for clarity: I am giving up graduating a year early for financial backing in college.

So, your exact situation is going to be unique, but there’s no reason you shouldn’t be able to get alternate funding to do college. Could you give more specifics about your situation and I’ll see what I can do or who I can put you in contact with?

You make good points about how to develop agency, but your section on how it’s lost feels incomplete to me.

For instance, as a child my parents had a mostly hands-off approach and let me do what I wanted, but because I’d spent so much time in front of the PC from a young age, the main thing I wanted was to play video games (this was in the late 90s and early 00s, before YouTube and social media). Games aren’t necessarily bad, but they give you pre-packaged goals to complete, when it would be healthier to learn to develop goals on one’s own.

This also ties into the issue of boredom: the easier it is to get rid of boredom (eg via games or feeds), the less one needs to explore to stop being bored.

As for school, I was somewhat contrarian and eg argued with my teachers, but because I lacked goals and ambitions of my own, I adopted those of the school, i.e. getting good marks. And one of the major downsides of that is that marks count down from perfect, which is not at all how real life works; I suspect that some of my perfectionism and risk aversion comes from that time.

(Plus having to get up way too early due to school is probably also not conducive for agency and motivation.)