Building Blocks of Politics: An Overview of Selectorate Theory

From 1865 to 1909, Belgium was ruled by a great king. He helped promote the adoption of universal male suffrage and proportional-representation voting. During his rule Belgium rapidly industrialized and had immense economic growth. He gave workers the right to strike. He passed laws protecting women and children. Employment of children under 12, of children under 16 at night, and of women under 21 underground, was forbidden. Workers also gained compensation rights for workplace accidents and got Sundays off. He improved education, built railways and more.

Around the same time, Congo was ruled by an awful dictator. He ruled the country using a mercenary military force, which he used for his own gain. He extracted a fortune out of ivory. He used forced labor to harvest and process rubber. Atrocities such as murder and torture were common. The feet and hands of men, women and children were severed when the quota of rubber was not met. Millions have died during his rule.

The catch? They were the same person—King Leopold II of Belgium. Leopold II is a prominent example of a person who ruled two nations simultaneously. What made the same person act as a great king in one nation and a terrible dictator in the other? If neither innate benevolence nor malevolence led to his behavior, it has to be something else.

This post covers Selectorate Theory. We’ll come back to the story of Leopold and see how this theory explains it, but first, we have to understand the theory.

The theory takes a game theoretical approach to political behavior, by which I mean two things. First, that it’s built on a mathematical model. And second, that it’s agent and strategy based. That means the analysis doesn’t happen at the level of countries, which aren’t agents, but at the level of individuals, like leaders and voters, and that the behavior of these agents is strategic, and not a product of psychology, personality or ideology.

This abstraction makes this model more generally applicable beyond countries to any hierarchical power structure, such as small local governments, companies, and even small teams and groups, but to keep things simple I’ll only talk about it in the context of countries.

I will try to give a comprehensive overview of the theory based on the book The Logic of Political Survival. We’ll start with the basic framework, then go through the predictions and implications the authors talk about, then I’ll mention further implications I think the theory has.

I won’t go over the statistical evidence for the theory, except for a brief comment at the end, or over the mathematical model itself[1] - the post is long enough without it—but I might do that in future posts.

To give some background: Selectorate Theory was developed by Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, Alastair Smith, Randolph M. Siverson, and James D. Morrow.

They introduced it in The Logic of Political Survival and later the first two authors wrote a more public oriented version in The Dictator’s Handbook.

I want to thank Bruce, the first author, for reading this article before publication. I sent him a question, not even sure I would get a response, and mentioned the article, saying I’d be happy to send it to him. He responded in just two hours and agreed.

Also thanks to Shimon Ravid, Nir Aloni, and Daniel Segal for beta reading this article.

The Basic Framework

The theory is based on the idea that the primary goal of leaders is to remain in power, or put simply, to survive, and that the behavior of organizations can be predicted through the optimal survival strategy for the leader, which depends on various properties of that organization.

To do all that, we need to make some assumptions and build a simple model of a country and the people and groups in it. The theory doesn’t use abstract terms like “democracy” and “dictatorship” to define nations, instead, it tries to derive them from other properties.

The Groups

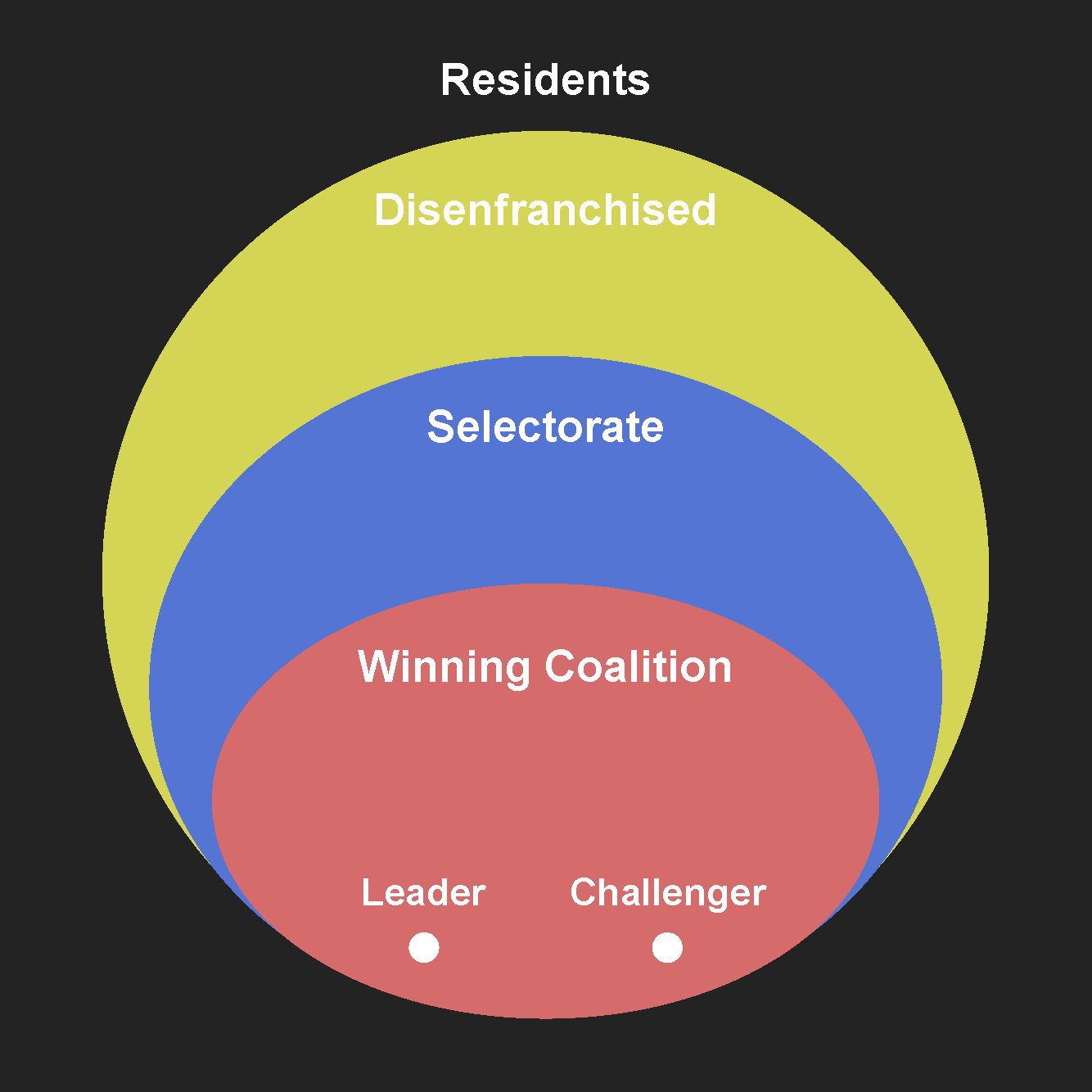

Every country has a leader, and usually also a challenger for leadership. The other residents of the country are split into three groups, the Winning Coalition, which is part of the Selectorate. Those not in the selectorate are the Disenfranchised.

The Leader

The leader or leadership is the one who can make policy decisions—this means Tax policy, and spending policy, which is the allocation of tax revenue to public goods and private goods.

These two assumptions about the leader are the basis for the whole theory:

No ruler rules alone. Every leader has to satisfy at least some people in order to rule. If they don’t satisfy them, they’ll be deposed.

The leader’s goal is to gain as much influence/power/money as they can, and to keep it for as long as they can. This may sound cynical. And it might be, somewhat. But it also makes sense. Holding office is required to achieve the leader’s personal goals—whether these goals are selfish or altruistic. To some people holding office isn’t that important, but these people don’t usually become leaders, and if they do, they don’t stay long.

The leader’s desire to survive stays constant, but the most effective survival strategy changes depending on the size of the other groups and other facts about the nation.

Residents

All residents engage in economic activity, pay taxes, and benefit from public goods. The size of the population determines the cost of providing public goods and increases how much tax can be collected. Residents may be included or excluded from the selectorate. Those excluded are called the disenfranchised.

The Winning Coalition

The Winning Coalition are the essentials, the keys to power—The people the leader has to satisfy to survive. The leader does that by rewarding them with private goods. The size of the Coalition (w) is one of two most important characteristics of a nation.

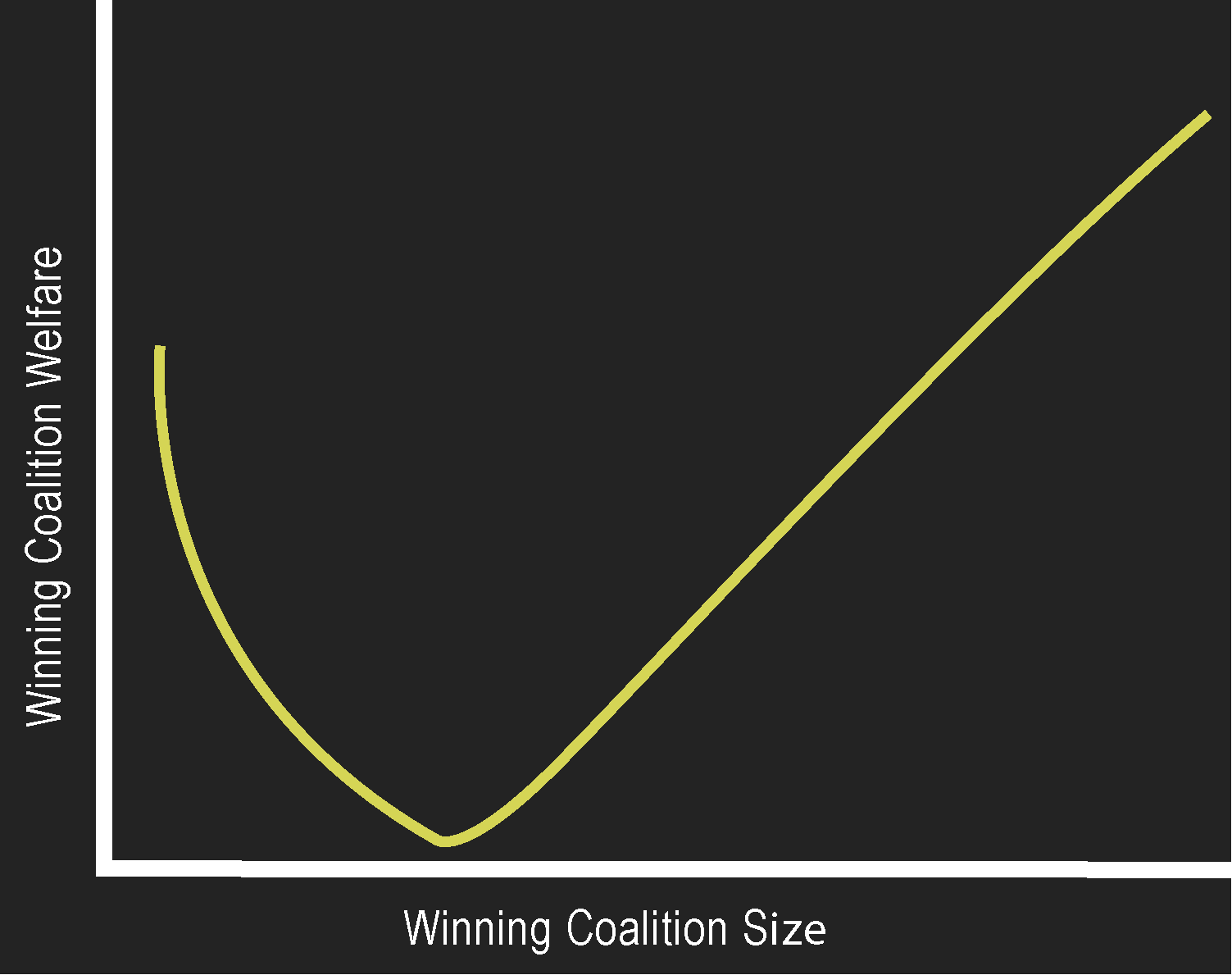

When the coalition is small, the leader can give private rewards to each person in the coalition. The more the coalition grows, the more expensive it becomes to produce private rewards for all coalition members, so the leader starts producing public goods instead.

This creates an interesting dynamic. When the coalition is sufficiently small, making it smaller is within a coalition member’s interest (as long as they aren’t the ones getting ejected, of course) since it lets them demand higher pay from the leader. As the coalition gets larger, there comes a point where it’s better for the coalition to expand, as all of them already get so little private goods, that they can all benefit more from the leader creating more public goods and less private goods.

We’ll see how small winning coalitions create autocracies and monarchies, and large coalitions create democracies.

The Selectorate

The Selectorate are those who can influence who gets to be the leader (say, by voting). The size of the Selectorate (s) is the other most important characteristic of a nation. They do not get private rewards from the leader, but still benefit from public goods. The base rate probability of being included in the coalition for any selectorate member is w/s.

The selectorate wants the winning coalition to expand, since then more money will be spent on public goods, and it increases their own chance of getting into the coalition. They don’t want the selectorate to expand as that decreases their chance of inclusion in the coalition—though this effect gets weaker as the coalition grows and more public goods are produced.

In the real world, common characteristics societies use to divide people in and out of the selectorate include birthplace, lineage, skills, beliefs, knowledge, wealth, sex and age. In the Coups and Revolutions section, we’ll see how military ability matters especially.

The disenfranchised

The disenfranchised are those who don’t have any influence over who gets to be leader. They too do not get private goods, but still benefit from public goods. The disenfranchised want the coalition to expand for the same reason as the selectorate. They also want the selectorate to expand so they may be included, but have no established way of making that happen—other than violence and asking nicely.

The Challenger

The Challenger is a person that challenges the current leadership in order to replace it. The challenger has a commitment problem—they have to get support from at least some members of the current coalition to win, but even if they promise to those who defect to their side that they will get more rewards than they currently do, they can’t guarantee that, or even guarantee that they’ll remain in the winning coalition at all.

The challenger can be anyone, but challengers from within the current coalition have an inherent advantage—they automatically get and take one supporter away from the current incumbent.

The challenger usually has a similar interest to the current incumbent (except who’s the leader, of course) since they wish to replace and get the same benefits as the leader, or more. For example, if the winning coalition grows, the country the challenger is trying to take over now has a larger coalition, which makes it less valuable.

Economy

Every game theory model has to state what agents desire and get value from, and every model of a country needs to model some basic economics.

In this model the things people value are:

The untaxed portion of their economic activity

Leisure

Public goods

Private goods (only available for coalition members)

And the leader values:

Above all else—staying in office. If the leader fails to stay in office nothing else matters.

And, if they remain, tax revenue not spent on public or private goods.

In the mathematical model these are precisely defined utility functions with diminishing returns and temporal discounting. If you don’t know what that means, you can ignore it.

Economic Activity and Leisure

Residents split their time between economically productive activities, which we’ll shorten to work, and economically unproductive activities, which we’ll shorten to leisure.

More specifically, work refers to activities that can, and leisure to activities that can’t, be subjected to:

Taxes

The leader decides on the tax rate, and collects the revenue.

The theory defines the tax rate as the percentage of total economic products the government extracts from the residents. No complex tax policies here—any such policy is simplified to that definition for analysis. But as we’ll see, the theory does make predictions about more complex tax policies.

When the tax rate is 0%, residents split their time equally between work and leisure. As the tax rate increases they work less, until at 100% they spend all their time on leisure.

As people work more their income increases, which further increases the money available for taxation. Together this creates a tension between tax rates and GDP (the sum of what is produced by the economic activity of residents).

High tax rate > Less productive economic activity > Lower GDP overall

Low tax rate > More productive economic activity > Higher GDP overall

The tax revenue is a percentage of the GDP, so the leader always wants to find the tax rate that will create the most revenue.

Spending

The leader splits their tax revenue between private goods and public goods. Whatever isn’t spent on those is the surplus, with which the leader can do whatever they want—engage in kleptocracy and keep it to themselves, invest it in some pet project, or keep it as a cushion against future political rivals.

Goods are assumed to be “normal”, such that more is always better.

The optimal spending strategy for the leader requires finding how much needs to be spent on the coalition in total, and how much of that should be split between private and public goods.

Private goods only benefit coalition members. The pool of private goods is divided between the members of the coalition, making the value of private goods shrink as the coalition size increases.

Public goods are indivisible and non-excludable—they benefit everyone and have to be provided to everyone. Think roads, defense, education, sewage, the grid and communications. The price of public goods rises with the size of the population.

It’s not necessary that any one good will be a pure private or public good—the theory simply deals with how much is spent on each type. Almost any public good will also have private benefits. If in the real world one of the things I listed as a public good is excluded or divided, it just becomes partially private.

Loyalty and Replaceability

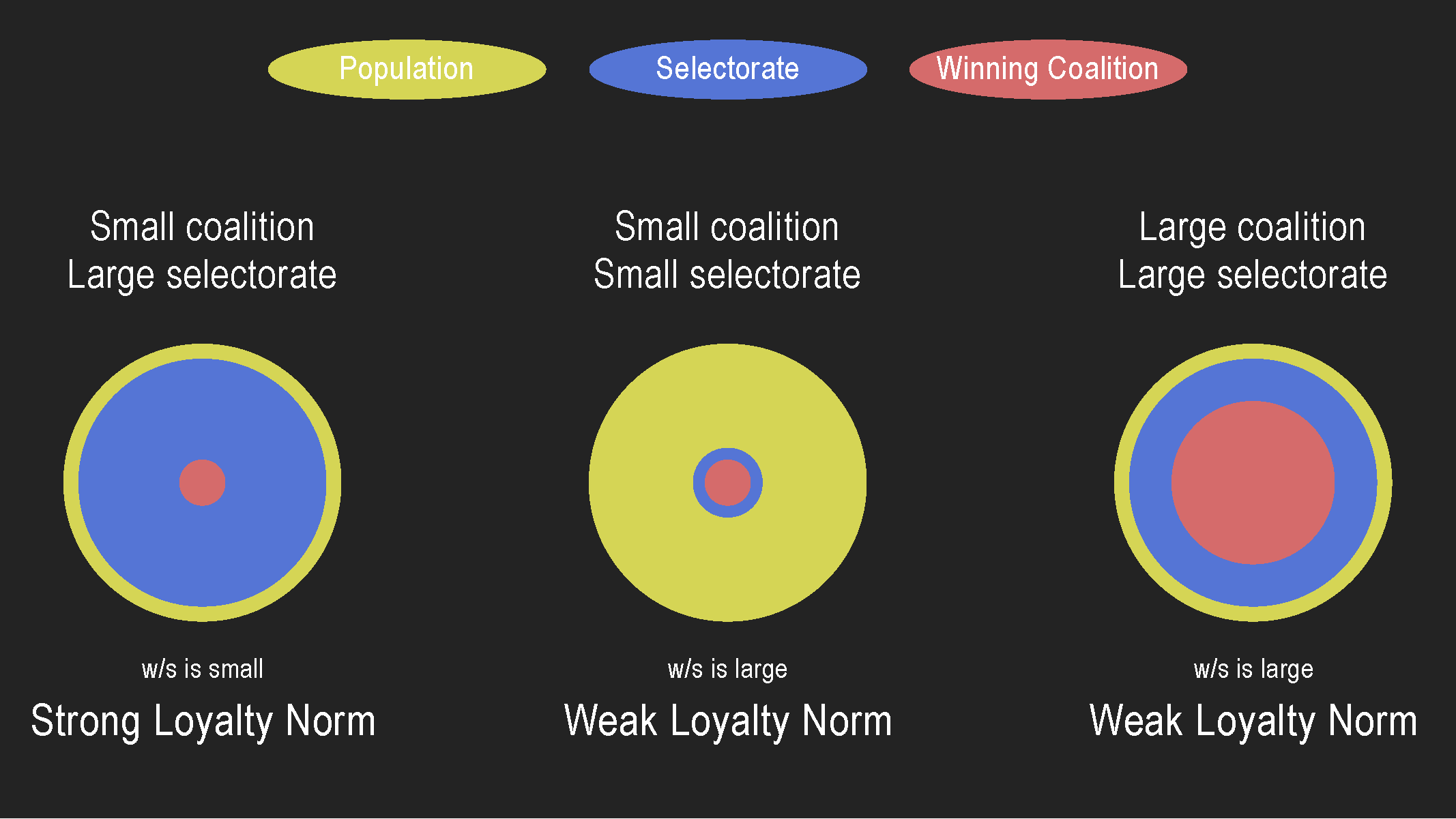

The loyalty norm refers to how loyal to the leader are the coalition members . It is defined as the size of the winning coalition divided by the size of the selectorate (w/s) and it is also the base rate probability that a selectorate member will be part of a winning coalition.

A strong loyalty norm happens when coalition members are easy for the leader/challenger to replace. A weak loyalty norm happens when it’s hard. The larger the selectorate is compared to the coalition, the more replacement options there are, which makes it easier to replace coalition members.

Selectorate size close to coalition size > Large w/s ratio (closer to 1) > Hard to replace members > Weak loyalty norm.

Selectorate size much larger than coalition size > Small w/s ratio (closer to 0) > Easy to replace members > Strong loyalty norm.

A weak loyalty norm means members of the coalition are more likely to defect to the challenger (since the probability of being included in the coalition is higher), and will require more spending from the leader to stay loyal. A strong loyalty norm means low chances of defection, and less required spending. Needless to say—Leaders like strong loyalty from their supporters.

This creates two competing effects on the coalition’s welfare. On one hand, expanding the coalition reduces the amount of private rewards each member gets, on the other hand, if the selectorate size is kept constant, it increases the total amount spent on the coalition.

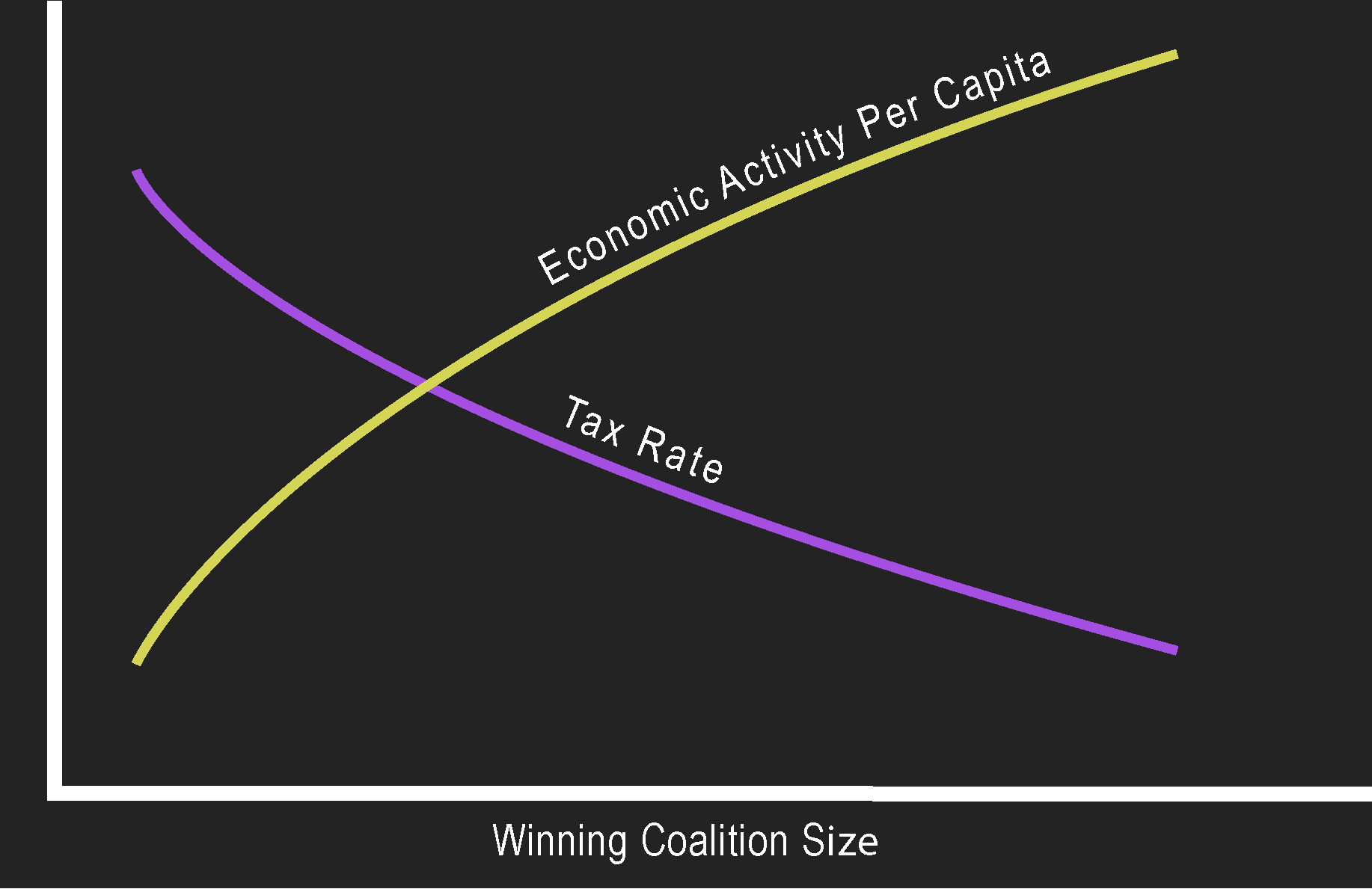

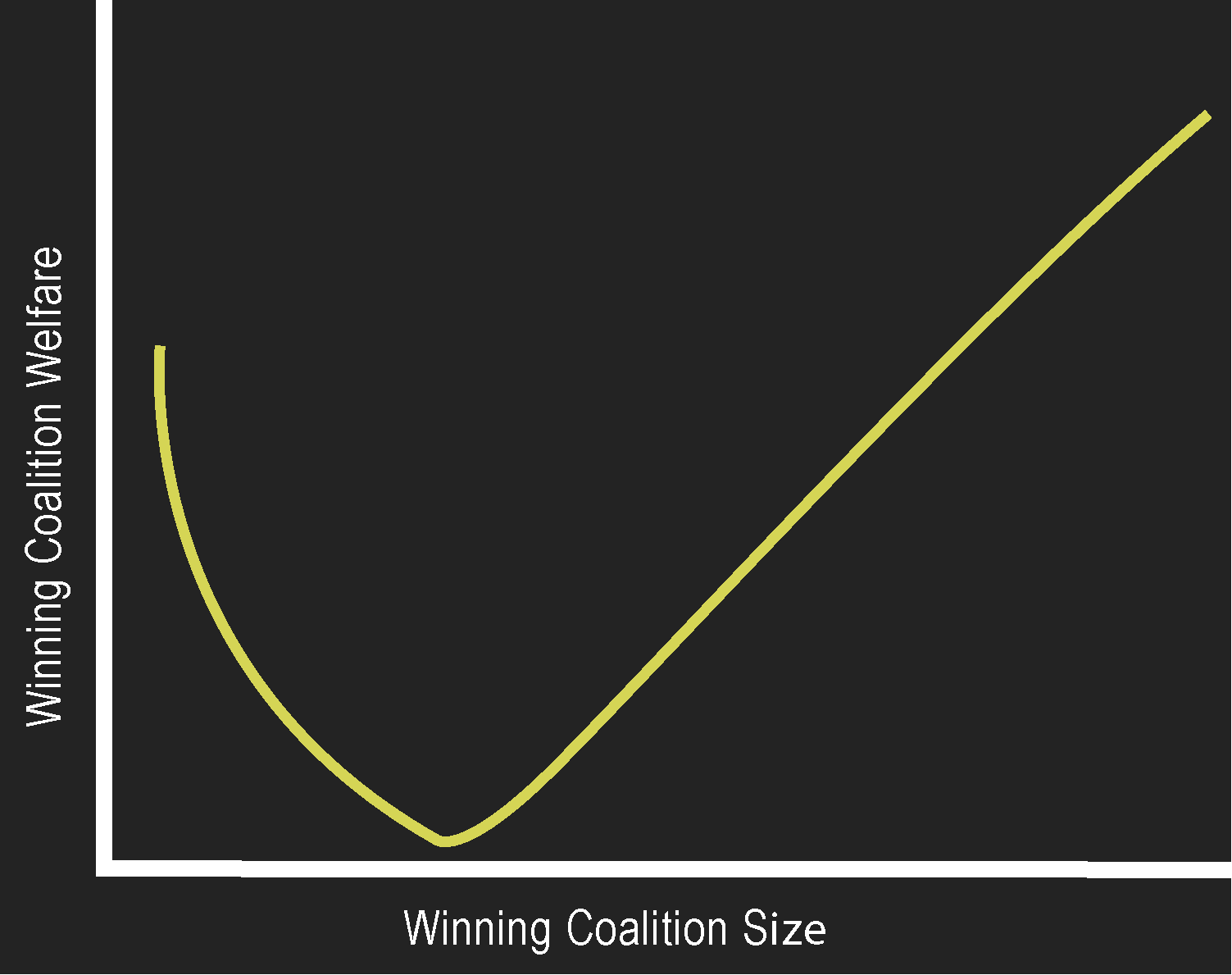

The following graph shows the relationship between the size of the coalition and these two effects.

Whether the coalition prefers to shrink or expand depends on where they are on this graph.

Coalition members prefer weak loyalty. When they’re on the left side of the graph they only want to do so by shrinking the selectorate, since expanding the coalition would hurt their welfare, but on the right side of the graph both options are good for them.

Shrinking the coalition without shrinking the selectorate will increase loyalty, but if the coalition is small enough the extra goods compensate for it.

Affinity

Affinity represents the idea that there’s some bond between leaders and followers independent of policy that can be used to anticipate each other’s future loyalty. All else being equal, people prefer to support leaders they have affinity for, but they won’t support a leader with worse policy due to affinity. It is used in the mathematical model only for tie breaking, and isn’t necessary for any of the main conclusions of the theory.

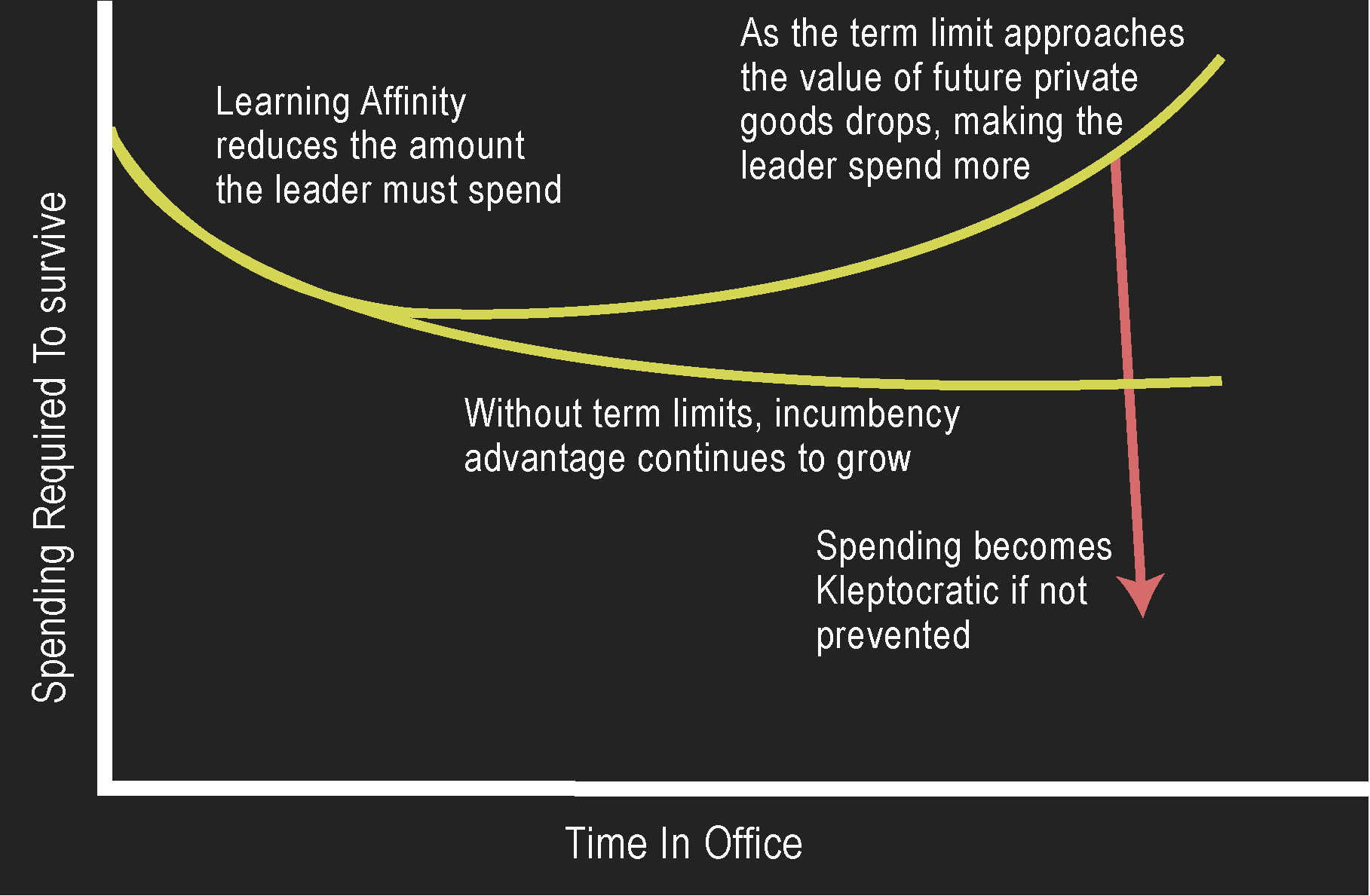

Leaders include in the coalition those they have the most affinity for. But, affinity has to be learned, and can never be known perfectly. Affinity is learned by staying in power. Challengers can have some knowledge of affinities before coming into power, but they’ll always learn more once they’re in power, and will remove and add coalition members as they do.

This asymmetric knowledge of affinity creates the Incumbency Advantage, expanded upon in the next section.

Deposition

The deposition rule defines the circumstance under which an incumbent leader is deposed. In the book they use a deposition rule called constructive vote of no confidence, which simply means a coalition of size w is both sufficient and necessary to stay in office (though not sufficient to get it in the first place). For the challenger to win, they must both have enough supporters that they can create a coalition of size w, and get enough people to defect from the current leader so that they lack w supporters. In other words, if less than w of the incumbent’s coalition supports the incumbent and at least w of the challenger’s coalition supports the challenger, the incumbent is deposed and replaced by the challenger. Otherwise they stay. Hence the amount of people who’s choice actually matters is never greater than 2w.

(The authors say that other deposition rules are plausible, but produce similar results, so they focus only on this one. We’ll take them at their word for now and do the same, since we’ll need to reproduce the mathematical model to see for ourselves.)

Coalition members who are only in the Incumbent’s coalition will always prefer to support the incumbent, likewise for the challenger’s coalition. Hence the decision depends on those who are in both coalitions, and on them the challenger has to compete with the incumbent, by offering a better deal.

The incumbent, to stay in office, has to at least match the challenger’s offer. So the incumbent’s strategy is to maximize the surplus after offering their supporters at least as much as the challenger’s best possible offer.

Incumbency Advantage

The incumbent has the advantage, since they have better knowledge of affinities and can promise inclusion in the coalition and private goods more credibly, while the challenger cannot credibly promise to keep supporters in their coalition. The Incumbency Advantage is inversely related to coalition size, as the larger the coalition the less private goods matter.

The more the selectors know the affinity between them and the challenger, the lesser the incumbency advantage, and the more they’ll be willing to defect. The incumbent counters that by oversizing their coalition, so they can punish defectors and still retain power.

The risk of defection moves from the risk of not being included in the challenger’s coalition, to the risk of being excluded from the incumbent’s coalition, or a mix of the two.

With the model in mind, we can see how the interaction of all these interests and incentives imply and predict various political behaviors.

Scope and Limitations

But before I get into the implications and predictions of the theory, I want to lay out the scope of the theory and its limitations.

The model doesn’t distinguish between one ruler having all authority to set policy and a large group of legislators all capable of setting policy. For the purposes of the theory, they’re treated as an individual and their inner group dynamics aren’t addressed. This might sound like a big shortcoming, but I think the theory does exceptionally well even with democracies, considering that it abstracts the decision making process so much. Also unaddressed are questions of separation of powers and checks and balances.

The theory assumes no limitation on the implementation of policy. The theory has implications on how inefficiencies are addressed and how strategies are implemented, as far as they can be described as goods, but not on what the strategies themselves are.

The model treats goods very abstractly. It does not deal with the question of which goods are prioritized (beyond public and private).

The model also assumes all members of all groups to be identical (except for affinity). There are no differences in competence. Particular interests (beyond what is covered above in economics) like protecting the environment, advancing science, or buying lots of yachts are not represented. Leaders don’t represent people who share their opinions, but those who share their interests (and are in the coalition).

The theory naturally lends itself to being fractal—meaning every group might have subgroups with a similar structure, where the leader of the subgroup is an individual from the super-group. For example, a member of a country’s selectorate or winning coalition might be the mayor of a town. With that said, the analysis in the book focuses on one level at a time, and doesn’t consider interplay between levels (Though see bloc voting later in the article, which comes close to that).

That said, we should see that the insights from this theory have implications on all these questions when explored on their own.

Implications

With all those limitations in mind, the authors still extrapolate the implications of the model to a vast array of subjects, giving many concrete predictions. In this section I’ll try to give a comprehensive overview of these implications and predictions.

Form of Government

The three general clusters of polities produce the characteristics of various regime types we’re familiar with.

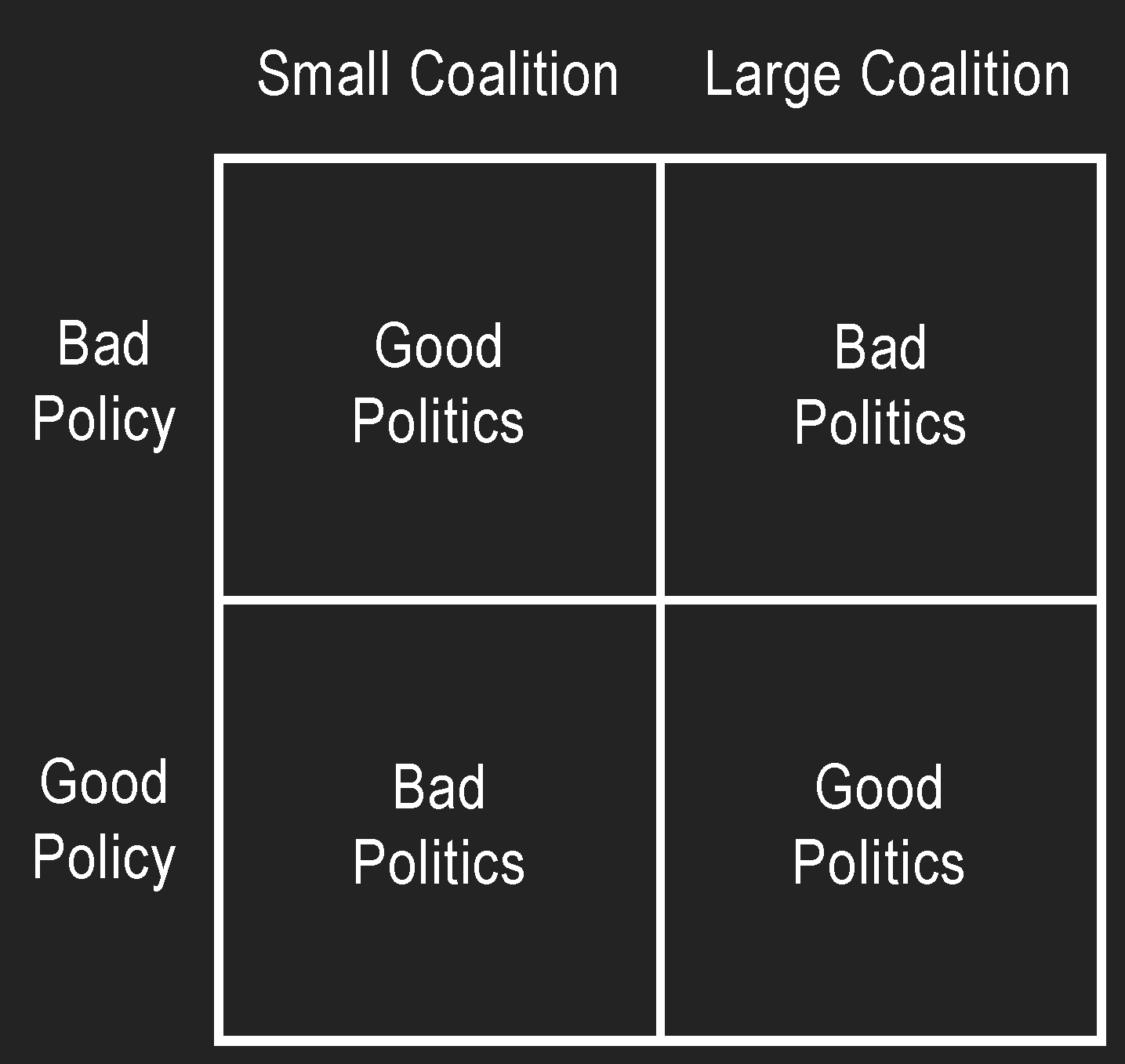

Large winning coalition systems resemble democracies—The leader requires a large supporter base, near or totally universal suffrage is common, plenty of public goods are provided and relatively little private goods, taxes are lower and economic productivity is higher.

Small-coalition, small-selectorate systems resemble monarchies and military juntas—The leader requires a small supporter base chosen from a small group such as aristocrats, priests and military persons, little public goods are provided and many private goods, people aren’t rich. Examples: Old England monarchy, Saudi Arabia Monarchy, Argentine Junta in 1976-1983

Small-coalition, large-selectorate systems resemble autocracies—The leader requires a small supporter base chosen from a vast pool of potential people who otherwise usually only participate in rigged elections, the amount of public goods is tiny and the amount of private goods big but smaller than in monarchies, the leader extracts the vast majority of people’s wealth and people are extremely poor. Examples: The soviet union, North Korea, Maoist China.

Smaller variations in size can account for variations within these regimes. It’s hard to say which of two democracies is more democratic, or what makes it so, but if we can estimate the winning coalition of both, it’s easy to say which is larger and what we should expect based on that. Not all democracies are the same, and neither are monarchies and autocracies—some more extreme and some milder.

I will sometimes use these regime types instead of specifying coalition and selectorate sizes, but remember what it represents are coalition and selectorate sizes. I do it mostly because it makes for less awkward phrasing, but also to reinforce the connection.

Transitional Democracies

When autocracies transition to democracies and expand the selectorate faster than they expand the coalition, the loyalty norm increases, which mimics the structure of a more autocratic system where the coalition is smaller relative to the selectorate. In such cases transitional democracies will temporarily exhibit more autocratic behavior like kleptocracy and willingness to start wars. This shouldn’t happen in transitional democracies that either increase the coalition first, at the same rate, or faster than the selectorate.

Presidential VS Parliamentary Democracy

In presidential systems the leader is usually elected directly by the people. In parliamentary systems the people choose a group of legislators which choose the leader themselves. As we’ll see in the next section, this means they require less votes to be elected, leading to a smaller coalition.

In parliamentary systems a further distinction can be made, between single-member district system, and party list proportional representation system. The former can create winning coalition as small as a quarter of the selectorate, or even less. The reason is that if the leader requires approval from half of elected legislators, and each of them require approval from half of their constituents, then the leader only requires approval from half of their constituents. Under plurality voting with more than two candidates (either for leader or legislators), it can require even less than half to win an election, which means a leader may be able to win with even less than a quarter of voter approval.

Party list Proportional Representation Systems tend to behave more like presidential systems, and shouldn’t lead to coalitions as small as single-member district parliamentary systems

The US, which has a presidential system but also has indirect elections through the electoral college, is a spacial case.

Federalism and Localism

The authors predict that corruption will “rise as one moves down the ladder from the central governments to state or provincial governments and on down to city, town, and village governments. Each successive layer relies on a smaller coalition and so provides more incentive to turn to private rewards rather than public goods as the means of maintaining loyalty. That incentive may be partially offset by the central government’s incentives to protect the rule of law, one of the central public goods it can be expected to provide.”

Federalism should let people benefit from both the benefits of large states and the benefits of small states.

Correlated Support, Bloc Voting and Indirect Election

The basic model assumes selectors are independent—the choice of one selector doesn’t influence the choice of another. But of course that’s not the case in reality. If we relax this assumption we can see how correlation in selector support effectively reduces coalition size.

The more people’s choice of support one person can influence (how many people their support correlates with), the more valuable they are as a member of the coalition, and the less the people influenced are. This applies to influential writers, speakers, celebrities, prominent community figures, owners of media outlets and so on.

Bloc voting is when a group votes similarly, usually based on the directives of one person.

In such a case that person becomes highly valuable as a member of the coalition, since their support is effectively equivalent to the size of the group that follows them. The leader would want them in the coalition, but not their followers.

Whether the followers benefit from the bloc leader being in the coalition depends on whether that leader shares their rewards with them, which will depend, like just the leader of the country, on the structure of that group (See note about fractality in Scope).

When leaders can’t reward people directly for their support, like in democracies where the vote is anonymous, they may still be able to reward groups. For example in Israel each ballot box is counted independently, and then the results from each ballot box and in each town is made publicly available. You can see the last election results here. This makes it very easy for politicians to invest more in places that support them and ignore those that don’t.

Bloc voting can be institutionalized through indirect election, where instead of directly choosing the leader, citizens choose electors who choose the leader for them.

The US has the electoral college. In Israel the prime minister is chosen by the Knesset. In both cases they’re not completely free to support whoever they want, the US electors can have limitations set on them by the states, and in Israel Knesset members need to be careful of displeasing their supporters, but in both cases it still reduces the influence of the people on the final outcome.

(The Dictator’s Handbook splits the selectorate in two to make this distinction between those who can potentially influence, which they call the “nominal selectorate” or the “Interchangeables”, and those who actually choose, which they call the “real selectorate” or the “Influentials”. Though this distinction is useful for bloc voting and indirect elections, it’s not consequential elsewhere, so I chose not to use it.)

Selectorate theory suggests that leaders have an interest to increase things that cause vote correlation such as ethnic, racial, religious, linguistic and other social divides. Residents benefit instead from increased independence of votes.

Term Limits and the Verge of Deposition

Leaders that expect to be deposed the next time they’re challenged have nothing to lose, but much to gain if they can manage onto hold to power. Therefore they’ll be more willing to do reckless things to survive, like going for a diversionary war.

A term limit creates two opposing effects.

It reduces the incumbent’s advantage, because they can’t supply private goods beyond the end of their term. This forces the leader to work harder to please their supporters.

It removes any reselection incentives by decoupling policy performance and survival, making the leaders stop working for the state, and turn kleptocratic.

The second effect comes from having nothing to lose, but since there’s also little to gain from reckless actions, the leader is more likely to turn to kleptocracy to make the best of the remaining time than to do something that will keep them in power. Civic minded leaders may use this freedom to take actions that the public would like but the coalition wouldn’t.

Post-office consequences for kleptocracy can reduce the second effect.

Enforcing term limits requires the winning coalition to remove the incumbent. Since in small coalitions the value of inclusion and risk of exclusion are higher, the members don’t want to enforce the limit and risk exclusion. This is why autocracies rarely have them, democracies often do, and some autocracies (mainly those with rigged-elections) have fake, unenforced term limits.

Political survival

The theory predicts that leaders in autocracies survive longer in office than in democracies, with monarchies in between.

This stems from the Incumbent’s advantage in guaranteeing inclusion in the coalition and promising private goods. So as the coalition expands and public goods become more important, the incumbent’s advantage diminishes.

Small coalition > competition is over the provision of private goods > The incumbent has a big advantage

Large coalition > competition is over the best public goods policy > The incumbent has a smaller advantage

In the early period in office the new leader still hasn’t learned affinities and sorted out his coalition, and therefore he lacks the incumbency advantage. Competitors will prefer to depose them as quickly as possible to take advantage of that. Therefore the early phases are most dangerous, but if the new leader survives them, they can persist for very long. This affects small-coalition systems more than large ones since their leaders are more dependent on private goods. This creates a higher variability in tenure in small coalition systems than large coalition systems.

Autocracies often have leaders like Stalin and Gaddafi who ruled for 39 and 42 years respectively. But they also more often have leaders like Bachir Gemayel who only survived two weeks in office before being assassinated. In democracies most elected leaders serve their full term, and are voted out after one or several terms if they don’t hit a term limit.

Former leaders are dangerous to current leaders, as they’re similar to a challenger with very good mutual knowledge of affinities with their supporters. The more important political survival is to the leader, the more incentive new incumbents have to permanently get rid of (say, by killing) the deposed leader. This leads us to expect that deposed incumbents are most likely to be killed or exiled in small coalition systems, and even more so when the selectorate is large. This can be seen as another reason leaders will want to keep power, though that’s not included in the model.

Death

When leaders are terminally ill, coalition members know that soon they will stop receiving private goods. This breaks their loyalty and drives them to defect. It might even become a competition of who defects more quickly to the new leader.

This makes small coalition leaders hide their health status from their supporters. This effect diminishes with coalition size as private goods become less important.

One way leaders can mitigate it is by having credible heirs who will take their place but keep the same coalition. Then coalition members have less to worry about not being included in the next coalition, and are happier to stay loyal.

Longtermism

Everything Leaders do they do with the purpose of keeping and gaining power, therefore as long as the coalition doesn’t know, any effects their policies have after they leave office are unimportant. Policies that will have a good effect in the future are good only if the coalition knows. Similarly, Policies that will have a bad effect in the future are bad only if the coalition knows.

As we saw in the last section, democratic leaders survive much less than autocratic leaders, so although autocratic leaders provide far less public goods, we can expect them to invest far more in the long term.

Even though we can expect regular public goods like rule of law, education, and infrastructure to be much better in democracies, we should expect to see that trend disappear for long term goods like green technology, carbon capture, AI safety, pandemic preparedness, and so on. Green technology is a slight exception in that list, as it is a long term good heavily valued by most democratic coalitions.

Autocrats invest more in the long term, but for themselves and their friends, not the public.

Term limits should make this even more extreme, as leaders cannot even hope to last more than usual or come back after a time.

Competence

We can model competence as an ability to produce more goods from the same pool of resources. You can think about it as competent leaders paying less for goods, or as competent leaders simply having more resources—the math is the same.

Competent leaders and challengers are able to offer more goods than their opponent, and so find it easier to attain and retain office.

If the competence of the challenger is known, the leader will take it into account in his spending strategy—spending more against a competent challenger and less against an incompetent one. As far as the challenger’s competence is unknown, the leader has to make a bet on how much to spend to be confident about surpassing the challenger’s spending ability.

Since competent leaders spend less, they have more surplus revenue to use however they like.

Over time, all systems would select for competence. But the selection pressure is much higher in large coalitions than small coalitions.

Economic Effects

Taxes

There are three constraints on tax rates:

High taxes diminish how much people work. This tends to be the limiting factor in autocracies.

The coalition is affected by taxes, so it has to be compensated. This tends to be the limiting factor in democracies.

Tax collection isn’t free, it requires resources and people to collect them.

As the coalition shrinks and the selectorate expands, autocracies tend to extract as much resources as they can from residents to give large rewards to the coalition and keep large amounts to themselves.

In small coalition systems, the coalition is compensated with private goods, which In the real world could also be tax exemptions. When the coalition is large, the leader cannot compensate them as much, since public goods cost more, and has to lower the tax rate.

Low taxes can also be considered a public good, which are inversely correlated with coalition size.

The theory predicts that as the winning coalition shrinks, taxes grow, and as the coalition grows taxes shrink.

Small coalition > High tax rate

Large coalition > Low tax rate

The lower tax rate in democracies is offset by the higher economic activity.

Though not part of the model, in the real world collecting taxes isn’t free, and we can expect that the higher the taxes the more people would try to evade them and the more collecting them would cost. This can also offset the lower tax rate in democracies, and act as another limit for autocracies.

But you’re probably thinking, “I live in a democratic country and I pay high taxes, what’s up?”. Indeed, many people pay high taxes in democracies—which seems counter to what the theory suggests—but it’s part of a progressive tax system. There isn’t one tax rate for everyone like the abstraction in the theory. In some places, under a certain income you don’t pay income tax at all. And there are various extra benefits for things like getting married and having children.

On the other hand, autocracies often don’t report correct tax rates or extract resources from citizens in roundabout ways, like forcing them to sell produce to the government, which the government then sells internationally at a much higher price. Autocrats may even raise tax rates beyond the point that maximizes revenue as a form of oppression.

We can also expect that the more competent at providing public goods the government is the more large coalitions will approve of higher taxes, but still not nearly as high as in autocracies.

The result should be that autocracies extract more resources in total from residents than democracies. We should also expect autocracies to tax the poor the most and the rich the least, while expecting democracies to do the opposite.

Economic Activity, Leisure and Black Markets

Per-capita income is directly related to coalition size.

This graph shows the functional relationship between coalition size, tax rates and economic activity predicted by selectorate theory.

Everyone would like not to pay taxes while their fellow citizens continue to do so (well, at least everyone that doesn’t assign much importance to notions of fairness). As taxes grow people are more tempted not to pay them, and instead engage in the black market.

Leaders never want people to avoid paying taxes. But, they might offer that as a private reward to coalition members, either in the form of tax exemptions in the law, or through selective enforcement of black market laws.

The theory predicts that as the coalition shrinks, people will engage more in black market activities, and leaders will enforce anti black market laws more selectively.

Spending and Welfare

As loyalty decreases, the proportion of revenue spent goes up (and surplus goes down), and as the coalition expands more of that spending goes towards public goods.

Some things considered public goods by the authors and are expected to increase with coalition size:

Protection of property rights, protection of human rights, national security, Rule of law, free trade, transparency, low taxes, education, better balanced markets, healthcare and social security.

In general, anything considered a public good by the coalition is expected to increase with coalition size.

Economic Growth is predicted to increase with coalition size since evidence shows it’s related to some of the things considered public goods.

The authors also predict that “the total value of private goods will be higher in the initial period of incumbency—the transition period from one leader to another—than in subsequent years and that the overall size of the winning coalition will shrink after the transition period.”

Corruption

The authors suggest 3 reasons for corruption, all of which are much worse in small coalition systems, and exacerbated by strong loyalty norms:

Complacency: As far as reducing corruption can be considered a public good, small coalition leaders have no interest to pursue that and instead prefer to be complacent.

Sponsored Corruption: Allowing corruption can be a private benefit given to supporters.

Kleptocracy: The stealing of wealth from the state directly by the leader.

I think there’s a fourth mode of corruption that is more common in large coalitions, is consistent with the theory and explains why democracies still feel so full of corruption. I explain it in the Gifts section under Further Implications.

Additional Sources of Revenue

In the basic model the only source of revenue for the leader is tax revenue. But it’s easy to see what would be the effects on the country from an extra revenue stream for the leader. We’ll explore three possible sources: Natural resources, debt and foreign aid.

Natural Resources

An abundance of natural resources can create another income stream for the leader and reduce the leader’s dependence on the economic activity of citizens.

In small coalition systems, this allows the leader to raise taxes even further.

In large coalition systems, it allows the leader to lower taxes even further.

National Debt

The basic model assumes that spending can be lower than the tax revenue, but cannot be higher. Later in the book the authors check what happens if that assumption is removed and spending is allowed to grow beyond revenue.

Debt acts like another source of revenue and increases kleptocracy.

Foreign Aid

Monetary foreign aid is usually given mostly to small coalition systems, where residents are poor and are in need of it. But if the resources are given to the leader to distribute to the population, the leader is expected to take much of it to themselves.

This gets worse when the leader is in crisis too. If the leader lacks resources to provide private rewards to their coalition, they will have an even greater incentive to distribute foreign aid money away from the public and, in this case, toward the coalition.

If a body wants to give foreign aid and wants the leader to make political reforms in the public’s favor, they have to condition the aid on the reform. Otherwise, aid given before a reform helps the leader fund rewards for his coalition, and is more likely to prevent these reforms rather than incentivize them.

Selectorate theory suggests that to be effective at improving the lives of residents, foreign aid should be conditional on prior political reforms, especially ones that hurt political survival. The aid should be transferred to independent organizations and administered by them, without interference by the recipient government. Evaluation of the success of aid should focus on outcomes, and not just how much aid was given. More aid should be given to those who demonstrate effective use of it.

But wait, what reason do leaders even have in providing foreign aid to other countries according to the model? Foreign aid is part of foreign policy, which is discussed later, and can influence the policy of the receiving country. That influence can be a public good if it aligns with the interests of the citizens.

Immigration and Emigration

When people feel that the system doesn’t work in their favor, they have three options:

Exit: Leave the country to a more favorable place.

Voice: Try to change the system.

Loyalty: Stay loyal and wait for better times.

This section will focus on the first option, and the next section will focus on the second.

In this model, the reason for emigrating is to increase your access to public goods and, if you’re lucky, private goods, so emigration is expected intuitively to be from poor polities to rich polities, and from small-coalition systems to large-coalition systems.

Disenfranchised, and selectorate members to a lesser extent, are most likely to take this option. Coalition members already benefit from their position, and are unlikely to be better off elsewhere.

Polities are affected by emigration. Every emigrant is one less person that can be taxed. In non-proportional systems, every selectorate member who emigrates also weakens the loyalty norm. Emigration especially harms small-coalition leaders, who benefit from kleptocracy, and they are likely to prevent it. We see that in autocracies like North Korea and the Soviet Union.

Receiving polities are also affected by immigration. Immigrants increase the population size and the price of public goods. If they are enfranchised it expands the selectorate, and in a proportional system, the coalition as well—increasing spending on public goods. If they are not enfranchised, the population grows but the coalition shrinks in proportion to it, making the leader spend less on public goods.

Polities may make immigration easier or harder, making them more or less preferable for emigrants. When large-coalition states make immigration easier, they hurt the leaders of small-coalition systems by making it easier for their subjects to leave.

Potential emigrants have to weigh their decision against how difficult immigration is, and how rich, public good oriented and welcoming their target nation is.

Since there are many countries, the barriers to immigration are easier to overcome than the barriers to emigration.

I find Switzerland an interesting case study for immigration policy. It’s very hard to gain Swiss citizenship, point-in-fact, nearly 25% of Switzerland’s residents aren’t citizens, or in the language of the theory, are disenfranchised. But these are mostly foreigners that came there knowing they won’t get citizenship. More than that, these mostly aren’t refugees who are looking to run away from some terrible country, but well-off people living in democratic countries where they’re either in the winning coalition or have a high chance of getting into it (though, in democracies that matters less).

Reading Martin Sustrik’s post on the Swiss political system, I intuit that they have a large minimum size for the winning coalition. Most of that coalition doesn’t want to expand the selectorate and bring more people in, and yet due to its size, Switzerland is producing so much public goods that people prefer to be disenfranchised in Switzerland than enfranchised in their home country.

Coups and Revolutions

If migrating isn’t a good option, people can try to alter the system. There are several ways people may go about doing that—From passing laws, to constitutional amendments, and up to assassinations, coups, revolutions and civil wars.

Protests and Revolts

Selectorate members with a small chance of entering the coalition might seek to expand the coalition in hope they’ll be included, or just throw out the current members and hope to replace them (“Seize the means of production”).

The disenfranchised have no chance of entering the coalition as long as they remain disenfranchised, and need a more fundamental change.

These are the groups most likely to rebel against small-coalition, large-selectorate systems.

The winning coalition is expected to oppose these attempts, as they have different interests. But they also have their own way of changing the system:

Coups and Purges

The leader and coalition may also take action to change the system. Remember, Leaders want to shrink the coalition and expand the selectorate. The coalition wants to expand the selectorate, and to either shrink or expand the coalition. We’ll call the act of shrinking the selectorate or the coalition by removing some of its members purging.

Whether the coalition prefers to shrink or expand depends on where they are on the welfare graph. When the coalition is on the lowest point of the graph, where both expanding and shrinking the coalition increases their welfare, they’re conflicted on which direction to go in. Some may support reduction while others support expansion.

Purging the Selectorate

Given the chance, after a coup for instance, coalition members are glad to purge the selectorate, as it weakens the loyalty norm and forces the leader to spend more. Though the total spending increases, this doesn’t benefit the selectorate and disenfranchised much, as most of that spending is directed towards the coalition.

Purging the Coalition

The leader is always happy to purge the coalition. For the coalition it’s more complicated.

Members of a coalition on the left side of the welfare function can benefit from purging the coalition as long as they’re not the ones purged, as they will get a larger share of the rewards. But, if the coalition shrinks while the selectorate doesn’t, the loyalty norm is strengthened and the total amount spent on the coalition goes down. Which effect dominates determines whether coalition members benefit from their fellow members being purged or not.

Purging the Selectorate and the Coalition

This is the optimal purge for the non-purged, small-coalition members. They can get the benefits of both types of purges. Their share of private goods grows, and if the selectorate was reduced more than the coalition, such that the loyalty norm weakens, total spending also goes up.

Expanding the Coalition

On the right side of the welfare function, even non-purged coalition members never benefit from purging the coalition. Instead they benefit from expanding the coalition. But the leader would still like to purge the coalition, so they have conflicting interests.

This further predicts that once a coalition is far enough right on the welfare curve, they cannot possibly have anything to gain from shrinking the coalition. This predicts that the larger a coalition, the more stable the system will be.

Expanding the Selectorate

Leaders always want to expand the selectorate in proportion to the coalition, and the coalition always wants to stop them. Large coalitions are fine with expanding the selectorate as long as the coalition also expands proportionally.

Purging the Selectorate and expanding the Coalition

This is the ideal case for a coalition on the right side of the welfare graph, and the worst case for a leader.

Civil Wars and Revolutions

Going beyond protests and coups, the authors expand the model to talk about civil wars and revolutions.

The goal of revolution in this model is to either take control of part of the nation (creating a new one), or replace the existing selectorate with another (including the leader, of course). The American Revolutionary War is an example of the first, and the French Revolution is an example of the second.

The model suggests that revolutionaries would be motivated by the prospect of overthrowing the current system so they, the excluded, become the included. The revolution attempt is modeled as a civil war between the disenfranchised (the excluded), and those in the selectorate who chose to oppose them, where each side tries to rally people/strength to their side, and whoever has more wins.

Those in the selectorate can either join, oppose or ignore the revolutionaries. The selectorate has two advantages over the disenfranchised.

Those in power have an incentive to monopolize military ability to be able to defeat a revolution, so they either only train those in the selectorate, or induct those who are skilled into the selectorate. If instead the military was disenfranchised, they would just overthrow the system. So the first advantage of the selectorate is military ability. Formally, this is represented by a multiplier on their strength. Various things can change the value of this multiplier, like the technology available, but that’s outside the scope of the model.

The second advantage is a greater ability to mobilize, due to an asymmetry of motivation. The disenfranchised can benefit from the revolution if it succeeds and they become selectors, but stand the risk of oppression and death if it fails. Passivity is safe for the disenfranchised, but not for the selectorate. If the revolution succeeds the selectorate will lose their current privileges. But like the disenfranchised, fighting is dangerous for them and it might deter them from fighting back.

The revolutionary leader promises a new alternative system. The disenfranchised calculate the expected benefits and costs from joining the revolution, and decide to join if it’s worth it. The better the system the revolutionary leader promises relative to the current one the easier it will be to recruit. The ability of the leader to promise private goods in the new system solves the free rider collective action problem that would appear if they could only offer more public goods.

Selectors make the same calculation, and decide based on it whether to fight back. The better the promised system relative to the current one, the less inclined they will be to fight back. The worse it is, the more they’ll be willing.

This makes large-coalition systems immune to revolution. A new system with a large winning coalition isn’t better for the current selectorate, so a revolutionary leader can’t improve their situation. If the leader promises a smaller coalition, they will replace the current selectorate with their supporters and the current coalition would lose their chances of getting private goods and get less public goods. They will also have trouble recruiting, as even the disenfranchised benefit from the high amount of public goods, and they’re probably a much smaller group than the selectorate, making it impossible to recruit enough supporters to defeat the defenders.

Small-coalition, small-selectorate systems are vulnerable to revolution. There are way more disenfranchised than selectors, and their motivation to revolt is high. The selectorate, and especially the winning coalition, benefits greatly from such a system and will fiercely defend them.

In Small-coalition, large-selectorate systems, there are less disenfranchised, but the selectorate may have it almost as bad as they do, and will not be willing to defend the system—They might even join the revolution. Given the competing effects of selectorate size, the authors are uncertain what selectorate size would make revolutions more common, and do not make predictions. But they do predict that such systems have less chance of surviving a revolutionary movement so they focus their efforts oppressing the ability to recruit and organize for a revolution.

This leads to an expected difference in the members of the military in small and large coalition systems. Small coalition systems have to include the military in the selectorate, or else it would lead a revolution. Large coalitions don’t need to worry about revolution and so can professionalize the army and include people outside the selectorate.

Outcomes of revolution

I wrote that the revolutionary leader promises a new, better system, with a larger selectorate and usually a larger coalition, and indeed, the theory suggests that the leader is sincere when they make this promise. But once the revolution is successful and the revolutionary becomes a leader, their incentives become that of a leader, and suddenly a big coalition is not in their favor.

The model predicts that if unconstrained, leaders will choose small-coalition, large-selectorate systems. Yet some revolutionaries like Nelson Mandela and George Washington greatly expanded the coalition after they won. Therefore, if a revolution results in an expansion of the winning coalition, it must be due to constraints.

One form of constraint is a non definitive win. When Mandela’s revolution succeeded it wasn’t a decisive win, and they had to form a coalition agreement with the former power. The rules were not the decision of a single person.

Another form of constraint is not having a single definitive leader to the revolution. In America the revolution was a joint victory by the thirteen colonies.

Large-coalition systems are expected to have little severe anti-government action taken by residents. But in the absence of deterrence, selectorate theory predicts that small-coalition, large-selectorate systems will have the most, and the most intense, domestic resistance. That’s why they turn to:

Oppression

To prevent coups, revolts, and other forms of challenges, leaders can turn to oppress their population. We’ll see when and who leaders oppress the most, and how they go about doing it.

Every opposer compares the benefits of success to the risks of failure. Oppression deters opposers by increasing the risk of failure. To be successful, leaders intensify oppression with the expected gains of successful opposition, making the risk of failure match or overwhelm it.

Leaders use oppression to stay in power. The motivation to stay in power is a function of the value of holding office, and the risk from losing it. Small coalition leaders get the most value out of office, and also have the highest chance to be punished when deposed. Large coalition leaders get the least out of office, but are allowed to walk out with what they got. The incentive to oppress opposition increases with the motivation to stay in office. Therefore large coalition leaders have a low motivation to oppress opposition, and small coalition leaders will attempt to hold office by any means possible.

Oppressing Challengers

The greater the inequality between the welfare of the leader and the welfare of the coalition and selectorate, the more tempting it is to challenge the incumbent. To counteract that the leader will intensify oppression on challengers.

In large coalitions the disparity between leader welfare and coalition/selectorate welfare is small, and thus oppression of challengers is also small.

A larger selectorate (stronger loyalty norm) also increases the disparity of welfare and oppression of challengers.

Oppressing Defectors

Since challengers from the winning coalition have an advantage over other challengers, leaders more fiercely oppress their own supporters who lead challenges.

Leaders also oppress anyone who supports challengers, and especially their own supporters, as they’re the most influential.

Void of oppression, any selector not in the incumbent’s coalition will join the challenger’s coalition as that’s their only chance of entering the coalition. Oppression discourages that. The extent of this type of oppression grows with the benefit of inclusion in the coalition. Put another way, “a leader has the greatest incentive to oppress selectors when the selectors stand to gain the most from unseating them”, which is when the coalition is small.

Oppressing The Disenfranchised

Disenfranchised have an incentive to revolt when public goods provision is low. Small coalition leaders have a great incentive to oppress them.

Finding Oppressors

Just as no ruler rules alone, no oppressor oppresses alone. Those who carry out the leader’s oppression are more willing to do what it takes when they benefit from their rule.

Coalition members are an obvious choice. They’re willing to oppress any source of opposition. This explains why the military and secret police are key members of the coalition in autocracies.

Selectorate members may be willing to oppress the disenfranchised if they benefit from the current system, even if they don’t benefit from the current leader. This happens in small-coalition, small selectorate systems, as the loyalty norm is weak and they have a good chance to be included in the coalition.

Coalition members have a conflict of interest in punishing challengers from within the coalition, as they benefit from the existence of credible challengers to the leader. The leader provides private goods to their supporters so they don’t defect. If oppression removes all possible challengers, the leader no longer has to provide anything. Leaders can solve this dilemma for the coalition by hiring selectorate members to punish insider challengers. This could be the selectorate member’s way to get into the coalition.

Large coalition leaders should find it hard to recruit people willing to oppress their fellow citizens, as the benefits of inclusion are small. They can also count on getting back into power if they lose it due to the higher turnover rate in large coalition systems.

Credible Oppression

Like any punishment, oppression depends on the credibility of the oppressor’s threat to punish the oppressed. In particular these are the things required for credible oppression:

The leader is capable of retaining power and the opposition may fail. Leaders who lose power cannot punish those who opposed them, so threats are less effective when opposers believe they can succeed. Small coalition leaders are better at retaining power, and so are more credible oppressors.

Oppression has to be connected to opposition. Random oppression doesn’t deter opposition, but it does increase the motivation for it.

War and Peace

The authors start the sixth chapter with an excerpt from Sun Tsu’s The Art of War, and an excerpt from a speech by Casper Weinberger on the Weinberger Doctrine, to illustrate the differences between the approach to war in small coalition and large coalition systems. The full section is worth reading, but is too long to include here.

The authors set out to explain the phenomena of Democratic Peace—that democracies do not fight wars with one another—and more specifically, these empirical tendencies:

Democracies are not immune from fighting wars with non-democracies.

Democracies tend to win a disproportionate share of the wars they fight

Democratic dyads choose more peaceful dispute settlement processes than other pairings do.

In wars they initiate, democracies pay a smaller price in terms of human life and fight shorter wars than nondemocratic states.

Transitional democracies appear to fight one another.

Larger democracies seem more constrained to avoid war than are smaller democracies.

To see the consequences of selectorate theory on war, we have to expand the model to a dyadic model, where we have two polities, and set the rules of engagement between them.

In this model, when leaders enter a dispute with leaders of other polities, they each either decide to fight or negotiate a settlement. If either chooses to fight, they both choose how much of their available resources to commit to the war effort. Like anything else, any amount spent on defense is an amount not spent on other things. Who wins is a function of regular defense spending (a public good) and war effort spending (which comes out of the private goods budget).

Residents receive payoffs according to the dispute’s outcome (whether through war or negotiation), and if they’re coalition members, the resources not consumed in the war effort. Then the selectors in each state decide whether to retain to replace the current leader.

The size of the coalition changes war strategies by changing which type of good the coalition focuses on more, and therefore which one the leader does as well. In a small coalition the leader is best off saving resources for the coalition rather than spending them on war. A defeat, unless specified otherwise, affects everyone equally—it doesn’t affect the leader and coalition more than other members.

To clarify—It’s not the outcomes themselves that are better or worse depending on coalition size, but increased effort at winning decreases the ability to give private rewards, which is more detrimental to survival the smaller the coalition is.

So like in the case of taxes, it’s easy for the leader to compensate small coalitions for defeat, and difficult for large coalition leaders. Therefore, large coalition leaders try harder to win wars, and avoid them in the first place if they don’t think they can win.

Further, this means that large coalition leaders are more likely to win wars. And since two large coalition leaders both anticipate that both would try hard if they war, they’d rather resolve conflicts peacefully.

Small coalition leaders try less hard, but still sometimes fight wars because the cost of losing is smaller for them.

There is an exception though, leaders will always try hard if they worry that defeat will directly cause them to lose their position. For example in WW2 both small-coalition and large-coalition leaders were nearly certain to lose their position or their lives upon defeat, so they either tried hard or surrendered their independence for survival.

At the other extreme are wars that require little resources to win, which both large and small coalition leaders may be happy to initiate and invest the little it takes to win. Colonial expansion can fit this category.

Small coalition > Higher focus on private goods > Less available resources to spend on war > Higher chance to be reelected upon defeat > low motivation to win wars > Willing to fight both unlikely-to-win and likely-to-win wars > Less likely to win wars they start

Large coalition > Lower focus on private goods > More available resources to spend on war > Lower chance to be reelected upon defeat > high motivation to win wars > Reluctant to fight unlikely-to-win wars, but willing to fight likely-to-win wars > More likely to win wars they start

Since democracies are happy to take on easy wars, how aggressive they are is not inherent, but depends on the situation.

If we assume that lower casualties act like a public good—since the smaller the coalition the less casualties consist of coalition members or their children—then we can also expect democracies to care more about the life of their soldiers and have lower casualties. Same case for winning fast.

We’ll compare disputes between three pairings of polities.

Autocrat VS Autocrat

Neither tries hard if there’s a war. Each attacks if it believes that on average it can get more from conflict than negotiations. To paraphrase the authors, Because the war’s outcome is not critical to their survival, the decision to fight is more easily influenced by secondary factors not assessed in the model, like uncertainty, rally-round-the-flag effects, and personal whims of leaders.

Autocrat VS Democrat

Though autocrats are willing to fight, they are reluctant to attack democracies if they anticipate they will reciprocate with force. Since democrats try hard, autocrats know they’re likely to lose. However, since democrats are reluctant to fight wars they’re unlikely to win, they’re more likely to offer concessions when they aren’t certain enough they’ll win. This gives autocrats a strategy of creating disputes and making demands of democrats, who they know won’t be certain enough of winning, in order to take advantage of their concessions.

Therefore autocrats are expected to start many disputes with democrats, but few of them will escalate to violence.

Democrats are more likely to initiate wars with autocrats than with democrats, but still only if they’re likely to win. Autocrats are likely to fight back and not offer concessions, since the price of losing is smaller for them.

Israel, where I live, is a great example of this. How could such a small country constantly win wars against several countries much larger than it, even when they attack together? Some attribute it to Jewish ingenuity, some to Arab disorganization. This model gives a different perspective.

Though small, Israel is a democratic country, and all of Israel’s opponents are somewhere along the monarchy-autocracy line. So Israel tries hard, perhaps even harder than other countries would due to the worry that loss wouldn’t just be some loss of independence or an economic blow, but an existential danger, both to the citizens and, perhaps more importantly, the leader.

On the other hand, its opponents don’t try hard, and can only spend so much on war before displeasing their small coalitions.

Honestly, this paints a bleak picture for me, as it suggests Israel may have an incentive to keep these countries autocratic. On the one hand, a democratic Egypt or Syria is (according to the model) less likely to attack Israel. On the other hand, if they do attack the war would be far more devastating than any war Israel previously had, and it’s far more likely Israel will lose. And the size difference would make Egypt and Syria more likely to attack Israel than if Israel had a similar size to them.

Israel’s other front is against regimes that are weaker, and even much weaker, than it. Terrorist organizations like Hamas and Hezbollah aren’t a credible existential threat to Israel. Israel can conceivably attack Hamas tomorrow and land a decisive victory. It doesn’t, because the cost is high and uncertain. It would not be a popular move.

Hamas knows that, so they make relatively small attacks against the citizens of Israel (something a dictatorship couldn’t care less about, but a democracy cares a lot), and get concessions from Israel. When Israel does retaliate, it’s not enough to deter an autocratic leadership.

Democrat VS Democrat

A democrat will initiate war against another democrat only if they’re sufficiently sure they’ll win, or that their opponent will offer concessions instead of fighting back. A democrat will only fight back if they believe they have sufficiently high chances of winning, otherwise they will concede.

Foreign Policy

In the last sections we haven’t given much thought to why a leader would choose to go to war, except as one of two solutions to a dispute. We also didn’t give much thought to the question of what they intend to do after they win. In this section we’ll explore war aims, and how the outcome of war in the losing state is affected by the winner state. We’ll need to add a few more assumptions to do that.

Foreign policy regards actions leaders take to get an advantage in international competition against other nations, in order to survive domestically. The model assumes foreign policy efforts are a public good.

The winner in war either wants to obtain resources from the defeated state, force policy changes, or force structural changes (the makeup of the selectorate and the coalition).

These are treated as regular goods and are split by the leader between public goods, private goods, and personal benefit. War aims are a mix between private and public goods that depends on the size of the coalition and the selectorate—Small coalitions drive leaders to seek private goods in war, and large coalitions drive them to seek public goods.

The postwar settlement process is modeled as a struggle in which whoever spends more relative to the other gets more. Foreign policy spending is determined by coalition and selectorate size.

Commitment and Compliance

The settlement has to be maintained somehow, and various things can make it more and less difficult.

We’ll split settlements into ones that require active compliance from the loser and ones that only require passive compliance. The UN’s agreement with Iraq after the Gulf War that it would allow inspections of their disarmament required active compliance. Territorial changes only require passive compliance as the defeated state has to actively challenge the winner to get back territory. Active compliance is harder to enforce than passive compliance, and leaders take that into account when forming their war aims.

Further, It’s likely the defeated leader would like to go back to their previous policy if they could, leading to a commitment problem for the loser and an enforcement problem for the winner. Even if the loser wanted to follow the agreement and could credibly demonstrate that, internal pressures can stand in their way. If a challenger suggests a more attractive policy that includes breaking the agreement, it’ll be hard for the leader to survive without also breaking the agreement, especially in large-coalition systems.

If, however, the new policies are in the interests of the citizens and the coalition is large, the commitment and compliance problem is reduced.

Installing a Puppet

To mitigate the commitment and compliance problem, the winner can replace the losing leader and install a puppet.

Like any other leader, a puppet still has their own interests and faces domestic pressures. If the leader loses the ability to remove the puppet from its position it will stop being loyal to them. Still, Installing a puppet increases the chances of compliance, but requires further military investment to achieve a total victory. Winners who install a puppet are incentivized to also install a small-coalition, large-selectorate regime in the defeated state, since in these regimes leaders have the most power and survive longest.

Large coalition leaders are most likely to install puppets since they spend most on foreign policy.

Structural Changes

If the winner chooses to make structural changes in the defeated state—change the sizes of the coalition and selectorate, as well as who’s included—they will make them smaller if their own interests are different from the ones of the residents, and make them larger if they do.

If we look at the US’s history of modifying other countries, we can see Iran as an example of pushing a country in an autocratic direction, and West Germany and Japan as examples of pushing countries that had similar interests to them after the war in a more democratic direction. It’s important to note that in Germany and Japan’s case the move toward democracy wasn’t instant, but instead took several years during which both countries were managed from the outside. So the move to democracy can be very slow and costly.

Making the state more autocratic can help a puppet leader rule, so such structural changes often come together with the installation of puppets, while making the defeated state more democratic is unlikely to come together with installing a puppet.

This further strengthens the bleak image of Israel’s relation with our neighbors. If Israel just has it easier when her neighbors are autocratic, our foreign policy efforts are likely to keep enforcing it, even if citizens like me hope our neighbors will get to have better lives under better regimes.

Territory/Resources

Taking territory from the loser continues the war after it was already won, and the defeated leader can attempt to get the territory back, so leaders aim for territorial expansion only if they benefit from it. Territory can be valuable in two ways,

Strategic value comes from strategic territory that helps the state to win wars.

Resource value comes from resource-rich territory.

Autocratic leaders benefit more from resources than democratic leaders as they get to keep more to themselves. This also means that democratic leaders would be more willing to return resource-rich territory. Territorial expansion shifts resources from the loser to the winner, weakening the former and strengthening the latter.

Strategic territory increases the ability of the leader to provide the public good of security, and the ability to defend other gains from war. Autocratic leaders may value strategic territory for the reduction in resource requirement in defense, but democratic leaders value it much more.

Small coalition > Leader gets more value from resources and has lesser need to defend citizens > Prefers resource-rich land to strategic land > Less willing to give back resource-rich land > More likely overall to seek territorial expansion

Large coalition > Leader gets less value from resources and has greater need to defend citizens > Prefers strategic land to resource-rich land > More willing to give back resource-rich land > Less likely overall to seek territorial expansion

As usual, the size of the selectorate has a small “autocratic” effect on large coalition systems, and a more pronounced effect on small coalition systems.

Further Implications

These are four more things that I think the theory implies but are not discussed by the authors.

Satisfy != Benefit

Implicit in the theory, but not made explicit by the authors, is that the leader has to satisfy their supporters, but that does not necessarily mean doing what’s good for them. If a leader can make people believe policy x (which is better for the leader) is better than policy y (which is better for the people), the leader can do x, get the personal gains, and not lose support. This is part of why journalism is important, and why weak journalism fosters bad policy. In small coalition systems, it’s easy to simply censor information and suppress the press. Large coalitions won’t put up with that, but a flood of irrelevant information can do the job just as well, without reducing satisfaction. Charismatic leaders give less and get more.

Voting Methods

Selectorate theory implies that the most important thing about the way a leader is chosen, is how much of the population they have to satisfy in order to get and stay in office. So voting methods which reward being approved by a supermajority of the population should result in better policy for the people. I say reward instead of require because systems that require supermajority can become weaker and less stable. The authors give an extreme example of Poland in the 18th century which gave veto power to all legislators, which led to foreign powers easily stopping any decision being passed by bribing just one person. Also see Abram Demski’s Thoughts on Voting Methods which discusses voting methods and support levels.

Gerrymandering can also be used to manipulate the voting system into giving some people less voting power than others, thus making the coalition smaller.

Voting Age

The theory says that in large coalition systems, the less disenfranchised people there are, the better. In modern democracies usually the only people who are disenfranchised (except non-citizen immigrants) are kids. Which suggests a motive for lowering the voting age (see also). It also discourages any form of limitation on voting rights, such as intelligence tests or maximum age limits.

Gifts

In a small coalition system, especially ones with a large selectorate, the leader is almost always the richest, most powerful person in the country. This is of course because they can steal more from the state, but also because they stay for longer, and can extract much more resources from the population. Unless you become part of the coalition, any riches you get that draw the attention of the state can, and probably will, be taken from you.

This also means that usually no one under the leader can bribe them, only foreign parties.

In large coalition systems, this is very different. The leader can only steal so much from the state, only stays for so long, and cannot extract resources as they please. Combined with the prosperity large coalitions bring, this creates a situation where the leader is rarely the richest member in their country.

Thus it opens the opportunity to bribe the leader with gifts (and promises of gifts, lest they’ll be discovered too early).