Resurrecting all humans ever lived as a technical problem

Note: the newest version of this essay and its translations to various languages are available at this link.

One day, we might be able to bring back to life every human ever lived, by the means of science and technology.

And it will be a good day.

History

To the best of my knowledge, the idea was first described in detail by Fyodorov, a 19th century thinker.

Fyodorov argued that it is our moral duty to save our ancestors from the claws of death, to resurrect every human ever lived. And one day, we’ll have the technology.

If you think that the goal is a bit too ambitious for a 19th century thinker, here is another crazy goal of Fyodorov: to colonize space.

His pupil Tsiolkovsky framed it as a scientific problem.

Von Braun read Tsiolkovsky, and converted the idea into a problem of applied engineering.

And long story short, we now have robots on Mars.

As a side note, some of the biggest achievements of mankind were accomplished by the same procedure:

Set an outrageously ambitious goal

Convert it into a scientific problem

Ignore critics who call it unsolvable

Convert it into applied engineering

Solve it.

Today

The Fyodorov’s idea of technological resurrection is not as popular as space exploration. It was mostly forgotten, and then rediscovered by modern transhumanists (for example, see the excellent works of Alexey Turchin on the topic).

These days, we routinely resurrect the dead (only a few decades ago, a patient without heartbeat would have been considered legally dead).

But the current resurrection tech only works immediately after death, and only under very specific conditions.

Cryonics could help in many other cases, but it can’t work without a properly preserved brain.

An assumption

So, how do we resurrect Benjamin Franklin? Leonardo da Vinci? Archimedes?

There is no law of physics that makes it impossible to recreate the Archimedes’ brain. Even random motions of atoms will recreate it, if you wait long enough.

Let’s assume that the idea of “philosophical zombies” is BS. A precise enough replica of the Archimedes’ brain will indeed generate the Archimedes’ mind, with all the existential bells & whistles.

If the assumption is correct, then we can bring him back to life by reconstructing his brain, or by directly reconstructing his mind.

Methods

Below I present some methods that could achieve that. Of course, all of them are highly speculative (yet).

Method #1. Generate all possible human minds

The set of all possible human brains is finite (the Bekenstein Bound provides the absolute upper limit).

Thus, given enough computational resources, it’s possible to generate a list of all possible human minds (in the same sense, as it’s possible to generate a list of all 3-digit binary numbers).

The list of generated minds will include all possible human-sized minds: living, dead, unborn, and never-to-exist.

If two human minds are identical, then it’s one and the same mind (in the same sense, as two identical binary numbers are the same number).

Thus, if we generate a binary number identical to an uploaded mind of Archimedes, then we successfully resurrected Archimedes.

Judging by our current (ridiculously incomplete) understanding of physics, generating all the minds will require a computer vastly larger than the universe.

There are not enough resources in the universe to generate all possible books of 200 pages. And the average human mind is much larger than a book.

Another problem is what to do with the gazillions of minds we’ve generated (including trillions of slightly different versions of Archimedes). To run them all in real time, we might need to convert the entire galaxy into computronium.

Fortunately, we don’t have to enumerate all possible minds. We can apply some reasonable constrains to greatly reduce the search space. For example, we are only interested in the minds compatible with the human brain.

The search space could be further reduced if we use the crumbs (the method #2).

The method could even become computationally tractable if we combine it with the method #4.

Method #2. Collect the crumbs

Every human is constantly scattering crumbs of information about them – from ideas to skin cells. Some humans are also leaving more long-lasting traces – from children to books to bones.

A Friendly AI of posthuman abilities might be able to collect all the crumbs of information still preserved, and create realistic reconstructions of the minds that scattered them.

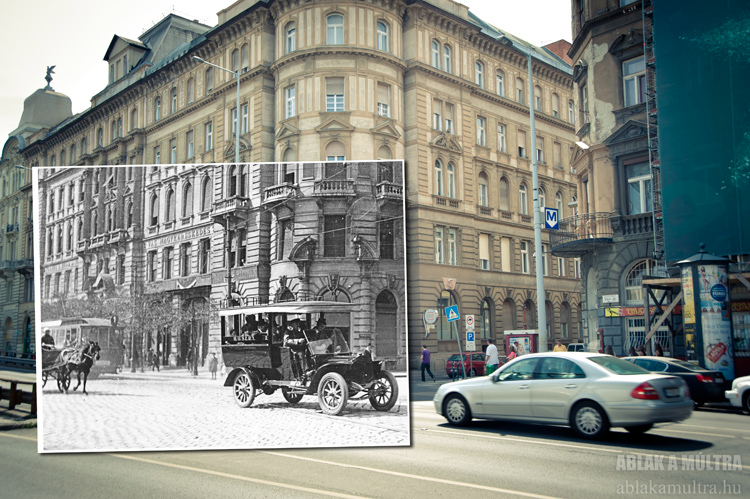

A digital reconstruction of the Antikythera mechanism (source)

For example, there is a finite set of brain-like neural networks that could write the works of Archimedes.

The set of 3rd-century BC Greeks who could write the works of Archimedes is smaller.

And if we find the Archimedes’ DNA, we could reduce the set further.

At some point, we could find the only human mind that satisfies all the constrains, and it will be the mind of Archimedes.

Method #3. Find a way to get arbitrary information from the distant past

It seems that the idea of time travel to the past contradicts the laws of physics (as we know them).

But there is no such a law that prevents us from copying some information from the past.

In fact, we constantly receive information from the past, e.g. by observing the light of the stars long gone.

Maybe there is a way to build a device that could show us the Battle of Waterloo, or any other historical event, exactly as it has happened, with the same fidelity as a modern digital camera.

If such a device is possible, maybe uploading minds from the distant past is possible too.

Method #4. Learn how to generate realistic human minds

This method is closely related to the method #2 (“collect the crumbs”). The idea is as follows:

Wait until billions of humans have uploaded their minds

Use the digital minds as a training data for an AI (with the minds’ consent, of course)

Add all the historical data we have, from ancient manuscripts to DNA samples

The AI learns how to generate realistic human minds, in a historical context

Generate all the minds, for all historical epochs

For example, we might ask the AI to generate all possible minds of 3rd-century BC Greeks who were able to invent the Archimedean spiral. One of the generated minds could be close enough to Archimedes to consider it a success.

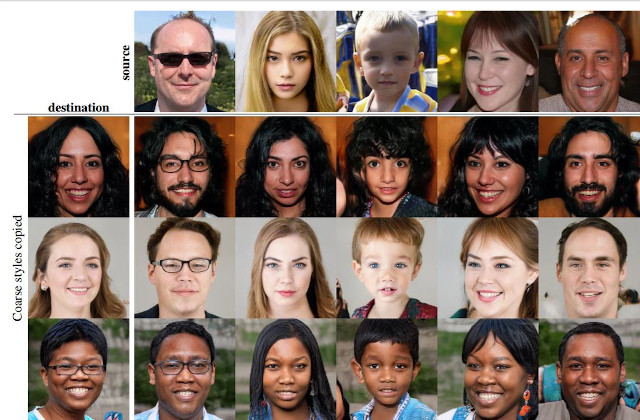

Already, there are AIs that can generate surprisingly realistic human faces (see the image below). Given enough data, maybe we can do the same thing with minds.

These people do not exist (source)

Method #5. Enumerate the parameters of the human mind

This method is closely related to the method #1 (“generate all possible human minds”).

Imagine that you’re a left-handed AI researcher who was home-schooled. You love clever Harry Potter fanfics. You’re a native English speaker. You ate some pizza in February 2021.

Thus, your mind has the following parameters:

mind_parameters = {

"handedness": "left-handed",

"job": "AI researcher",

"homeschooled": True,

"clever_harry_potter_fanfics_lover": True,

"native_language": English,

"ate_pizza_in_feb_2021": True,

# <many other parameters>

}Some of the parameters have a huge impact on the person’s behavior (for example, homeschooled). Other parameters usually have no lasting impact (like "ate_pizza_in_feb_2021").

As there is a finite number of possible human minds, there is a finite number of such parameters. And the number of impactful parameters could be quite small (perhaps in millions).

By enumerating all realistic values of the impactful parameters, we could reconstruct all realistic human minds.

This method generates approximate reconstructions. But they could suffice. For example, many people believe that they are mostly the same person as T years ago. If the difference between the approximate reconstruction and the original mind is smaller than the T-years-difference, then the reconstruction is good enough.

This method is much more tractable than the full binary enumeration of all possible minds.

The computational requirements could be greatly reduced if we enumerate only historically accurate minds (e.g. there were no AI researchers in the 3th century BCE). The problem of combining incomplete historical data with enumeration of minds is similar to learning Bayesian networks with missing data, a well developed field that already has some pretty efficient algorithms.

One could argue that the human mind is nothing like a video game character who has only a limited number of traits. But even in our current minuscule population of 7 billion, there are so many like-minded people making the same life decisions, we must conclude that the number of possible traits is indeed limited.

Some ethical considerations

How would you answer the following questions?

1) Imagine that a girl is in an intensive care unit. Her heart stops. If the right tech is applied, we can bring her back. Is it an ethical goal to revive her?

2) Imagine that a girl is a cryonics patient, frozen in liquid nitrogen. By any definition of the today’s medicine, she is dead. But if the right tech is applied, we can bring her back. Is it an ethical goal to revive her?

3) Imagine that a girl died in 1930. Except for a few bones, there is nothing left of her. But if the right tech is applied, we can bring her back. Is it an ethical goal to revive her?

I answer “yes” to all 3 questions, as I don’t see any ethical difference between them.

The value of saving a human life should not expire with time. It should not depend on when is the human in danger. Resurrecting is ethically equal to saving a human in grave danger.

But how to handle the people who don’t want to live anymore? Resurrecting them doesn’t make sense unless we also repair their will to live (the repair should be done under their consent, of course).

In many cases, some combination of these measures will suffice:

bringing back their beloved ones (we are resurrecting everyone anyway)

fixing the underlying organic problems (e.g. their gut microbiome causing suicidal thoughts).

conducting a comprehensive psychiatric intervention

But in some cases, none of this will help. How to handle such cases?

Also, how to handle mass murderers? If we resurrect everyone, then we also resurrect Hitler, and all the other bad people from the past (and maybe from the future). Converting them into decent people will be another huge problem (the conversion should be done under their consent, of course).

In general, I think the strongest argument against the resurrection idea is that there might be more ethical ways to spend the necessary (enormous) resources, even in a post-scarcity society.

Some projects could save more lives than the estimated 100+ billion humans awaiting resurrection. For example, if the heat death of the Universe is real and preventable, a post-scarcity society might decide to invest most of its resources into a solution.

But after the more pressing issues are resolved, we can (and should) start the resurrection project.

Some practical consequences

So, there might be a chance of bringing all humans ever lived back to life.

This includes Archimedes. And your grandma. And even you (especially, if you’re still procrastinating about cryonics).

Unfortunately, even after learning about this idea, you still need to exercise, and eat healthy, and avoid risking your life for dumb fun.

The entire resurrection idea is speculative. It might not work. It might be forgotten in a few centuries. Or we might become extinct in a few decades. The idea could give you hope, but it doesn’t make you immortal.

On the other hand, it’s a benevolent dawkinsonian meme:

if you promote the idea of technological resurrection, you increase the chance of bringing your beloved ones back to life by the means of science and technology.

Maybe resurrection is indeed a solvable technical problem. And maybe saving 100+ billion humans is a worthy cause.

Generating all possible minds and then picking out the one you want is identical to simply building the one you want. In the same way, finding a book in Borges’ Library of Babel is equivalent to writing the book yourself. In both cases, if you follow the improbability, all the work lies in determining which one you want.

A possible solution is to not pick out. Generate all possible minds (with some realistic constrains), and let them all live their lives.

If we have enough computational resources to run billions of slightly different versions of Archimedes, then we create billions of virtual habitats for them, and let them be.

One of them will be the Archimedes. We don’t know which one, but at least we succeeded in bringing him back.

I feel like the main thing to focus on here should be time travel—some seemingly-physically-impossible things are easier-in-expectation to do (because we may be wrong about physics) than some technically-physically-possible things.

While our current understanding of physics is predictably-wrong, it has no particular reason to be wrong in a way that is convenient for us.[1]

Meanwhile, more refined versions of some of the methods described here seem perhaps doable in principle, with sufficient technology.

You can make difficult things happen by trying hard at them. You can’t violate the laws of physics by trying harder.

Out of the many things that might be wrong about the current picture, impossibility of time travel is also one of the things I’d least expect to get overturned.

I agree. We still don’t know how 85% the Universe works (dark matter), and our main physics frameworks don’t play well with each other. It means, there is still a lot of undiscovered physics.

What we see as physically impossible today could become a mundane engineering problem in a few decades. Such transitions from impossible to mundane have already happened a few times (e.g. transmutation of elements).

Some kind of time travel, or at least time scanning (Option 3) seems the best option.

Potentially of interest, we have a dedicated subreddit on this topic: r/QuantumArchaeology

Love your subreddit (but I don’t like Reddit much and I almost never use it).

Most likely the information about humans who lived in the distant past has been permanently erased by various processes.

It is not possible to resurrect “all” humans—the space is too large. I estimate that there are roughly 10^11 bits of information to fully specify a human mind such that the remaining error is within normal day-to-day fluctuations i.e. normal existence. Thus the space of all humans has about 2(1011) points, which is approximately 10(1010).

I think a combination of DNA + social media history might come pretty close for people in the modern era.

But anyone from before the computer age who was cremated is gone for good. The DNA is pretty important in get you to the required number of bits.

I agree the first half of your idea. About the second half, I sketched a framework here: [link]. Might be relevant if you’re curious.

I think we should not assume that our current understanding of physics is complete, as there are known gaps and major contradictions, and no unifying theory yet.

Thus, there is some chance that future discoveries will allow us to do things that are currently considered impossible. Not only computationally impossible but also physically impossible (like it was “physically impossible” to slow down time, until we discovered relativity).

The hypothetical future capabilities may or may not include ways to retrieve arbitrary information from the distant past (like the chronoscope of science fiction), and may or may not include ways to do astronomical-scale calculations in finite time (like enumerating 10^10^10 possible minds).

While I agree with you that much of the described speculations are currently not in the realm of possibility, I think it’s worth exploring them. Perhaps there is a chance.

From the top of my mind, Aleister Crowley formally and explicitly asked not to be resurrected, assuming the plausible possibility of that happening ahead of his time.

I think it makes sense to resurrect him anyway. We don’t know what exactly he has disliked in resurrection, and he didn’t know what the future humanity can offer.

It’s safe to assume that only people with a severe mental illness choose to die. This is true in any circumstances, regardless of how tragic they are.

So, if there is no mental illness in play, and Aleister understands what exactly he is losing, he may choose to die again.

In the future where we can do technological resurrections of distant ancestors, the field of psychiatry will certainly be advanced enough to cure all or almost all suicidal patients (in many cases, the cause is as banal as a minor biochemical deficiency). Thus, such deaths will (almost) never happen.

I’ve been considering for years that I should write more, and save more of my messages and activities purely so I can constrain the mindspace for a future AI to recreate a version of me as approximate to my current self as years ago me is. As far as I can tell, this is fairly low effort, and the more information you have the closer you can get.

I just don’t see an obvious refutation for why an advanced AI optimizing for creating a person that would write/do/etc. all the things I have with the highest probability it can would be that different from me.

This technique for resurrecting Archimedes would work whether or not he was still alive, a “ressurection” that doesn’t need a prior “death” is not much of a ressurection at all. Would it soothe Archimedes’ fear of death to see himself being “ressurected” in this way in front of him? I think he would still very much like to not die in the conventional sense.

Apart from that problem, this suffers from what I’d call the Really-that’s-what-you’re-doing-with-computronium problem. Recreating past human minds would be a cosmic waste in my opinion, why explore the space of current human minds when you can explore the space of jupiter-brains? Or the space of matrioshka brains? Simulating past humans feels like using our current compute power to simulate lots of tiny ant brains instead of one human.

The space of Jupiter-brains is

indescribablyimmensely larger than that of human brains. A human brain almost certainly has fewer than 10^10^20 distinguishable configurations, while a Jupiter-brain probably has more than 10^10^40 configurations. Don’t let the fact that the number at the top is only twice the other fool you, these numbers are incredibly different in magnitude.The fraction of Jupiter-brain configurations delayed due to exploring the space of all possible human brains first is less than 0.000000...(10^40 zeroes)...0001%. So don’t worry about the waste of computing power.

Of course, both are utterly impractical to explore. With a computer the size of the observable universe that explores 10^100 configurations per second, it will take 10^10^20 seconds to explore just the human brain configurations. It will also take 10^10^20 years, because on these scales the change in the exponent between seconds and years is so small that it would require more decimal places than is worth typing. For that matter, the ratio in computing power between a universe-sized supercomputer and an abacus is likewise irrelevant.

People saying things like “just simulate all possible brains” are making implicit assumptions that can’t be supported in anything we’ve observed of the universe.

How can it take both seconds, and years, at the same time?

Because the number are so ridiculously huge that there is essentially no difference between seconds and years.

More precisely, I could have said “it will take 10^10^19.999999999999999999 seconds”, and “it will take 10^10^19.99999999999999999991″ years, respectively. Both would be wrong, because that communicates a degree of precision that isn’t present.

It’s really more like “it would take between 10^10^15 and 10^10^20 seconds”, because I don’t know the exact size of the reasonable state space for human brains. If I convert to years, it’s still “it would take between 10^10^15 and 10^10^20 years”.

Sure, from our current (very limited) understanding of physics, simulating all possible brains seems to be impossible. But should we assume it will forever remain impossible?

It would take more than 10^10^20 seconds to find prime factors of some large integers. But after we’ve discovered one weird trick, we can (theoretically) do it many-orders-of-magnitude faster. Maybe there are similar tricks for searching in the space of all possible minds.

Judging by the history, the Clarke’s first law is more fundamental than any law of physics:

When a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible, he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong.

From the linked article:

I should’ve been clearer, by “exploring the space of jupiter brains” I meant “making a single large jupiter brain”. In general I think computational ressources are better spent to build a few centralised very large brains than to simulate a very large number of small ones. I agree with everything you’ve said.

I agree, the technological resurrection idea should not be used as a reassurance in own immortality. It is much better to avoid dying than to rely on such speculations.

Why not both? We could save the 100+ billion lives awaiting resurrection, and then explore the space of jupiter-brains. Saving lives is not a waste of resources.

An interesting thing here is a possibility of cross-resurrection. It works as following:

I create a random mind with more or less coherent life-history.

As everything possible exists, it is resurrection of some really existed mind somewhere in multiverse.

Moreover, there are infinitely many other beings in the multiverse which also generate random minds.

Thus any mind will be resurrected, but in different branches of MWI.

While generating all possible minds some random things I thought about while skimming the post:

Is my mind from 1 second or 1 year ago the same mind as my mind right now? Are we interested in Archimedes mind from any specific point in time or just at any point in his life?

The state of the minds we’re generating in our search. Are we generating minds whose state is that of a mind that has experienced one billion years of torture? Is that bad? Stopping torture is good, no?

How many minds will be generated that did not want to be resurrected?

Some of this depends on the technical details of how traversing the space of possible minds works and also something like...can we generate a mind without “running” it? If we can generate a mind, and the mind isn’t running, are we OK with generating the tortured mind if we can inspect it in a not-running state?

If we’re just generating possible minds, how many will say “Yo, I’m Archimedes!” but actually have no relation to our historical Archimedes?

Excellent questions!

One possible solution is to resurrect the oldest version of the person, but before the onset of any irreversible brain damage. For example, we bring back the version of Archimedes from some minutes before his murder by a Roman soldier. But for many patients, the timing will be tricky to decide (e.g. slowly progressing Alzheimer).

I agree, such states of mind should be excluded, if possible. At least because they’re unrealistic, and thus are unnecessary increasing the search space.

If we use the method #2, many trillions of such minds will be generated. I think, in most cases, we can repair the will to live without a deep modification of the mind. But I don’t know how to handle the remaining cases. The least we can do is to give them a choice: do you want to exist or not? We gave them the second chance, and they should decide if they want to use it.

I think a mind who is not experiencing any suffering is not increasing the total suffering. For example, a cryonics patient who is still in liquid nitrogen—can’t suffer, because their neurons are not firing. Same for a digital mind who is not running (e.g. just a static file on a HDD, doing nothing).

There will be many trillions of such minds. I see two possible solutions: 1) we use some smart filtering to avoid generating unrealistic Archimedes, 2) we generate all Archimedes, real or fake, and just let them live their lives.

Regarding collecting crumbs, Brandon Sanderson wrote a fantasy story about it: The Emperor’s Soul.

Thank you! Will read it.

Another work of fiction on the topic is a science fiction novel by Philip José Farmer called “To Your Scattered Bodies Go”.

Speaking about fiction, the method #2 could create minds indistinguishable from the minds of some fictional characters.

For example, one of the generated minds could believe that his name is Harry James Potter-Evans-Verres. He could have the right personality, and vivid memories of all the relevant events from the HPMOR. It will be quite a shock to learn that you’re nothing but a fictional character reconstructed from a Harry Potter fanfic by some galaxy-scale posthuman machine.

Although I’m pretty sure Harry would support such a project.

I don’t see a real difference between your Method 2 and Method 3 excluding timetravel? Are you just trying to emphasize that there might be unknown unknowns or do you mean something different?

For example, the Archimedes’ work called On Sphere-Making is lost. We only know about its existence through references by other authors.

If our goal is to recover On Sphere-Making, we could try to reconstruct it from all the preserved information about it (the Method 2), using the references, historical data, a systematic search across all ancient parchments etc.

But if we have the tech that could directly retrieve information from the past (Method 3), we could just copy On Sphere-Making from the first manuscript.

How was it determined that “there are not enough resources in the universe to generate all possible books of 200 pages.”? Would love to know the math behind this.

My reasoning was as follows.

The typical book page contains about 3k chars (including spaces).

If we encode each char in UTF-8 (8 bit), a 200-pages book will contain about 5*10^6 bits (about 600 KiB).

Thus, to generate all 200-pages books, we must generate all binary numbers of the length 5*10^6 .

There are 2^(5*10^6) such numbers, or about 10^10^6.

There are at most 10^82 atoms in the universe. If we replace each atom with a (classical) computer, and split the work among them, each of the computers will need to generate 10^(10^6 − 82) books.

If each computer is generating one example per femtosecond (10^-15 sec), it will take them roughly 10^10^6 sec to finish the job.

It’s much much longer than the time before the last black hole evaporates (10^114 sec).

And this is only the generation. We also need to write the books down somewhere, which will require some additional time per book, and a hell lot of storage.

I suspect that the entire task can be done dramatically faster on quantum computers. But I’m not knowledgeable enough in the topic to predict the speedup. Can they do it in 1 sec? In 10^10^3 sec? No idea.

We could also massively speed up the whole thing if we limit it to realistic books, and not just strings of random characters. E.g. use only the relevant parts of UTF-8.

The estimate is based on my (ridiculously primitive) 20th-century understanding of computing. How will people think about such tasks in 1000 years is beyond my comprehension (as it was beyond comprehension 70 years ago to measure stuff in petabytes and petaFLOPS).

Maybe I’m missing something here, but say you do find a way to resurrect a specific human mind, we’ll take Archimedes for example—would this be the same Archimedes? Is this even your goal here? Do you wish to use this tech to actually bring back people you knew and cared about or do you view this more as a computational / archeological problem? In order to resurrect the exact same person, wouldn’t you have to hydrate that brain with their full life experience? (from their perspective) I don’t really see how your solution accounts for that, aside from the bread crumbs approach maybe, which still won’t help much there, even for the most recently deceased. But that’s probably not all, the biological body (microbiome ec) will probably need to match exactly as well to continue the exact same person where they left off. I get the idea of trying to improve and fix their bodies, but how can you be sure it kept the same person? For that reason, I too second the idea that it’s better to explore time travel and the fabric of time in order to solve that problem. If however your goal was always more scientific and you don’t care for exact matches, than personally I wouldn’t waste time resurrecting everyone—I would instead target the great minds of all times to help us solve even bigger problems.

You’re right, the goal is to bring the Archimedes back to life, not just some similar mind.

We humans are changing all the time. My mind from 1 year ago is different from my current mind (say, the difference is X percent). So, if you resurrect me, and the difference is less than X, then I don’t have to worry about the difference.

I also agree with you on time travel. If it’s possible, then it will be the best solution. Just mind-upload the person from the past, before they die.

It’s stuff like this that makes me glad this sort of thing is physically impossible.

There are two ways to look at that. Either you are not resurrecting the target, but instead creating somebody who is “off by one” from the target… or you are engaging in nonconsensual mind control.

From where I am standing, resurrecting somebody who is “no different except that they want to live” looks very much like resurrecting somebody who is “no different except that they want to have sex with you”, or “no different except that they love the dictator”.

Can we possibly agree that mind control is not OK?

Can’t a person even die without being harassed by busybodies?

While you’re at it, don’t go around simulating/constructing all possible human minds, without regard for their individual preferences. It would be rude. And twisted charicatures that have weird desires to be there inserted into otherwise incompatible mind states would be pretty fucking creepy, too.

No, sorry, that would not be OK, either.

I don’t advocate for nonconsensual mind changes (edited the post to make it clear).

Imagine that your friend has a severe depression (e.g. caused by their gut microbiome), to the point of attempting suicide.

You have a medication that fixes their gut microbiome, curing their depression, with no side effects.

In such a situation, is it OK to ask your friend to take the medication? (with a proper medical consent etc).

If your friend takes the medication and thanks to it doesn’t have suicidal thoughts anymore, is it right to call the whole situation a “mind control by Jbash”?

Paramedics don’t abandon a patient because the patient committed suicide. They’re trying to save his/her life regardless. And they’re doing the right thing.

In a world where you can create whoever you want and fully resurrect people no matter when they died, life ethics will be drastically different from our own. People would kill themselves in spectacular ways just for fun, as today they would practice extreme sports (just to cite Prime Intellect).

As per our assumptions, Archimedes 2.0 is the Archimedes, the 3rd-century BC Greek thinker who was temporary dead but who will be alive again.

(in exactly the same sense, as some of the today’s clinically-dead patients will be alive, thanks to the modern medical tech).

Thus, the plan is not just create some minds similar to Archimedes, but to save the life of Archimedes himself.

I see resurrecting a long-dead person as morally equal to saving a contemporary who is in grave danger.

If these days someone creates children, and then endangers their lives, are we morally obligated to try to save them? I see it as a morally equal situation.

Trying to kill people is definitely a bad thing, even if you are sure that the murder will be unsuccessful.

There is also no guarantee that any of the listed resurrection methods will ever work.