How Large Language Models Nuke our Naive Notions of Truth and Reality

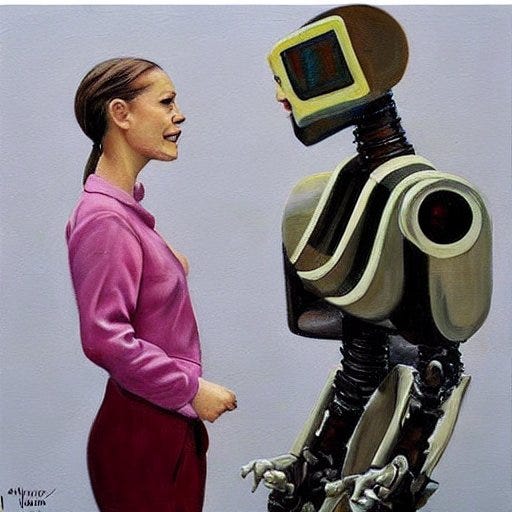

When AI can mimic human word strings by “meaningless computation”, what does that say about human word strings?

The best generative language models like ChatGPT-4 still astonish us with both what they can and can’t do. And that’s for one ostensibly simple reason: an AI still doesn’t “understand” what it’s doing. It can’t even “know” what we want it from it; only descend to whatever reward function it is given. That infamously introduces weird failure modes galore, many of which will likely be with us for a while (along with other issues like endless generation of fake news and propaganda). But this essay isn’t about AI helping, replacing or destroying us. It’s not about what incalculable admixture of fantastic and horrible awaits us in the coming AI wonderland I keep calling the Algorithmocene.

This post is instead about how generative AI creates an urgent need for all of us to stop for something almost no one has time for in our breathless, brave new AI world: a moment of metaphysical philosophy. Specifically, why now is a really good time to question how we think we know anything. What does it mean when we humans claim something is “true” or “real”? I would argue that an AI-powered post-truth world makes a fresh examination from first principles more urgent than ever.

So here are my pedestrian’s two cents.

Let’s start with the basics. Everyone is quick to point out that generative language platforms are just word prediction machines based on statistical models. They binge on ginormous training datasets and learn which words we humans tend to put together in which combinations in which contexts. That LLMs now do this so well contains an important lesson about us humans. Our word strings may be infinitely variable, but they also have a very high degree of predictability. That’s a key point to be picked up later.

For now (and isolated—ahem—concerns about AI sentience notwithstanding), let’s simply accept that all computers today mindlessly compute without “understanding” what they’re doing. But given how closely AI can now mimic human language, the obvious questions we should be asking ourselves are: How are our human words principally different? What do we humans mean when we claim to “understand” something? How do we know what is “truth”?

After all, we humans are more than capable of creating our own absurd chains of reasoning untethered to sound conclusions. Anyone who has ever taught math has seen struggling students “mindlessly” compute without understanding what they’re doing. When later explaining their work, they will often point to certain symbol combinations seen earlier and insist: “well, if these symbols were used here, why can’t they be used there?” And who among us has not despaired when listening to others explain their opposing views on a hot-button political topic. We want to throw up our hands and say “They don’t even understand what they’re saying! They’re just mindlessly mixing word strings picked up somewhere!” Finally, part of living a human life is to do and say all sorts of things we later scratch our heads over and wonder “what was I thinking!?”

So while we’re on the basics, let’s remember the most basic fact of life in the universe. We humans, like all living organisms, are essentially statistical prediction machines. Sometimes called the free energy principle by neuroscientist Karl Friston and followers, this basic thermodynamic insight traces its pedigree back to Erwin Schrödinger’s classic 1944 book What is Life? and even earlier to Ludwig Boltzmann. What characterizes life is not matter or energy, which are both abundant and expendable, but persistent ordered structures, which are precious and hard to maintain.

Statistical modeling is the only way living things can maintain their low entropy state against the never ending onslaught of statistical chaos. More broadly, any persistent ordered structure in the universe, whether a random rock in a stream or a random rocker on stage, can be understood as a statistical model of the disorder it constantly bathes in. Rocks in streams, for example, maintain their order by the sheer strength of the chemical bonds in their crystal structure. But they also interact with part of the stream flowing across their surface (forming what’s known in statistics as a “Markov blanket”, though in this case it would be a rather wet blanket). The mechanical stresses on the rock and the weak chemical interactions with different molecules in the stream are passive statistical models of the surrounding water’s pressure, temperature, pH, salinity and so on.

Living things on the other hand have to do more than just passively model. We have to proactively work to expel the entropy around and within us. That’s because everything life does — breathing, eating, thinking, sleeping and all that living stuff — creates new entropy waste that has to be exported to the rest of the universe. (Some propose that a strict maximum of entropy is exported, but that’s a stronger, nontrivial claim.) We do this via complex, orchestrated molecular machinations (aka metabolism) specific to each organism, environment and life history. These in aggregate modify both our internal state and outside environment in such a way that the entropy demons constantly trying to possess us are cast out into the world.

To focus here just on the generic concept more than any specifics or end result, we can think of an organism as being what engineers in control theory call a model predictive controller, or MPC. An MPC is just what it sounds like: a suite of statistical models that predict both an organism’s environment and its internal state, along with a suite of controlling actions to pro-actively maintain the organism’s internal order.

Again, everything an organism does that uses energy—which is everything all the time — boils down to the workings of an MPC. Anything falling outside of this framework starts to accumulate entropy and moves the organism from a state of living towards a state of dying. That’s just the basic math of life. All of which naturally invites, what else, a computer metaphor. We can even think of evolution as a selection for MPC “software” which runs on various “hardware” components in the environment, like water, minerals, sugars, nucleic acids and so on.

Be that as it may, at some point in our history, human MPCs evolved a unique feature. This feature is prompting me at this moment to move my fingers across this keyboard and you the reader to stare into a screen. That in turn links our mental universes across space and time in a dance of word strings created with recursive grammar — word strings that can be hierarchically linked to each other. The ability to link words, a bit like linking those plastic monkeys in a Barrel of Monkeys, is incredibly special. As far as we know, only the human brain makes words that are “sticky” enough to do this. In principle, it gives our universe of word strings the power of universal computation aka Turing Machines. To the extent that this feature presumably appears no where else in nature, one might even say we humans are Earth’s “first AI”.

As a brief aside, we most likely had no choice but to evolve complex language. Since humans left the forests for the open Savannah, we’ve always been uniquely unsuited for surviving alone in the wild. Slow and weak, without fangs, fur, claws or hooves, we only had our smarts and each other. Our only path forward was outsourcing our survival to everyone and everything we could find at hand. That requires a lot of purposeful communication and computation. So for those early pioneers of the genus homo, it was presumably either a) lucky set of mutations that enabled language to double as universal computation or b) extinction.

But however our language came about, the word strings we generate in speech and writing are still just part of our MPC machinery. Sure, human models have much more context and connectivity than current AI models. Our models are not only based on previously stored word strings from other humans. They’re vastly more complicated and influenced by statistical input data mostly invisible to us: accumulated life experience, surrounding culture, what we ate for breakfast, blood pressure, the weather — the list is endless. All the same: the thoughts we have, the words strings we stream, are 100% the output of our statistical prediction models. Just like an AI.

But if the word strings both we and AI spit out are just whatever our statistical models serve up, do they actually mean anything? For that matter, what is even the meaning of our supposed “meanings” if everything is just a string of, if you will, plastic monkeys? In the case of an AI we have no problem saying their machinations don’t inherently “mean” anything. Indeed, it’s the position taken for granted at the beginning of this essay. We’re generally quite fine with saying an AI merely plays a sophisticated “language game” of moving monkeys around.

To point out that we humans do principally the same thing may be an uncomfortable thought at first, but it is certainly not original to this essay. The 20th century philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein didn’t know about Markov blankets or AI, but his famous description of the human “language game” makes essentially the same point. The overlooked fact about human language, he noted, is this: We never really understand what words “mean” as much as we become skilled at using them. Or rather, what we call “meaning” is only our skills becoming so second-nature that we don’t even notice them. This should be obvious to anyone who has ever opened up a dictionary. Each word is “defined” in terms of other words, which is of course, hopelessly circular. Or rather, it would be hopeless if we didn’t already have the anchor of prior experience in simply using words. Wittgenstein’s insight seems painfully obvious in hindsight, but strangely enough seems to have escaped Western philosophy for over two thousand years (notwithstanding Shakespeare’s Juliet asking “What’s in a name?”).

And in fairness to all the past great thinkers who apparently missed this point, when taken to heart it does cut hard against the grain of deep-seated intuition. That’s certainly not at all what it feels like when we’re thinking, speaking or writing. The meanings behind word strings generated with the richness of complex language, especially if it’s on a topic we care about, seem to glow with their own incandescence. When we tell our loved ones how we feel, argue a political issue or describe a beautiful painting, we’re sure that we’re doing more than playing syntactical monkey games. This nigh self-evident view sits, for example, in the center of John Searle’s famous “Chinese Room”—one the most widely cited arguments in the philosophy of mind. In a nutshell, the thought experiment imagines a hapless translator of Chinese who doesn’t understand a word of Chinese, but can follow the detailed instructions (i.e. syntax) of a translation book. That such a translator is in principle possible is claimed to show syntax is not semantics.

Many others, notably the likes of Daniel Dennett and Douglas Hofstadter, raise extensive objections to the Chinese Room argument. Here I’ll just point out that, in the context of our MPCs, the distinction between syntax and semantics is something of an illusion. The illusion works so well because, for us MPC-beings who type into keyboards and stare at screens, the real syntax and semantics sit much, much deeper than the patterns of pixels in front of us. That is, the vast majority of our human “language game” is scattered invisibly throughout our bodies. It’s in our metabolism and nonstop entropy exporting. The syntax we see is just the tip of an iceberg that has a causal ancestry dating back to our birth. And that’s of course exactly where semantics, our sense of “meaning” lives. When viewed this way in their entirety, syntax and semantics for us MPC-humans are something like two sides of the same coin (apologies for once again mixing metaphors, but that’s what you get with complex language)

As another aside, this gives a rather natural way to view the difference between humans and current AI. An AI lacks “understanding” not because it is merely playing a language game (and certainly not because it runs on a silicon substrate), but because it doesn’t engage in model predictive controlling. Rather, its statistical models are more like the passive rock in the stream example earlier. It mirrors its environment without actively engaging it like a living MPC. The language game of a human is different. The same water flowing over a human body has to be pro-actively engaged in some way that costs energy and produces an entropy waste problem. Dealing with all of that is what makes water actually “mean” something to us that it doesn’t mean to an AI.

So finally, what does all this have to do with metaphysics; the meaning of truth, reality and all that? Everything, I would say.

In comparing ourselves to a generative AI that convincingly mimics our word strings, we have to face something important about ourselves. Our own sense of meaning is so visceral, hidden and integral to our being that it’s easy to forget they’re all just human meanings. When we throw around words like “truth” and “reality”, the MPC machinations at the molecular level that go into their syntax and semantics are almost entirely invisible. They simply feel so second-nature and unproblematic that we’re sure their meaning must transcend us. As the brilliantly affable Neil deGrasse Tyson likes to say “The great thing about science is that it’s true whether you believe it or not.” And another brilliantly affable fellow, Albert Einstein, was famously sure that the Moon is there even when nobody looks. (1)

Why are objections to Wittgenstein’s straightforward point about human language often so visceral? My guess is that, as noted earlier, human word strings are both infinitely variable and yet highly predictable. That puts them in the sweet spot for the brain’s dopamine reward system. In particular, the dopamine reward often associated with grand world-splainin’ words like “truth” and “reality” lends them more or less magic properties in our minds. We instinctively believe we need truth and reality but they don’t need us. Or so we all believed until Bell’s Inequality and a slew of famous EPR experiments made many of us pause with a big “… uh… hang on a minute…”

But we didn’t need quantum theory to teach us the naïveté of our instincts. Before Wittgenstein or any modern physics, the deep conceptual conundrums at the heart of any recursive language were already apparent. Many famous mind-bending examples from Russel’s barber paradox all the way to Gödel’s Theorem teach us this. Frankly, I think they beat us over the head with a frying pan. But we humans are nothing if not hard headed, and so we go on believing.

Just to be clear, the frying-pan-resistant-belief I’m panning here is NOT: “we humans in the 21st century see truth and reality as they really are” (that would be ridiculously naive, not to mention awkwardly convenient). Rather, the belief that the best discerning human minds tend to stubbornly cling to is basically the motto of the X-Files: “It doesn’t matter if we limited humans never see ultimate truth: The Truth is Out There!”

So powerful are our instincts in this regard that we’d rather tie ourselves into cognitive pretzels with metaphysical fantasy stories like “natural kinds”, “transcendental realism” and “Platonic Realms” rather than give them up.

By now I hope the hopeless incoherence of all these fantasies feels fairly obvious. In particular, they’re incoherent on their own terms. Once you admit that what you mean by “truth” and “reality” is a construction of the mind’s MPC modeling efforts, then you also admit your stories about truth and reality are mind constructions. And any meta-story you want to tell about your stories about them is a mind construction. It is then empty, meaningless and useless to try to talk of any of this existing outside the mind when every single word you use, like “truth”, “reality”, “exist”, “outside” and “mind” are themselves all mind constructions. We can’t jump outside the narratives of our human MPC any more than we can jump over our own shadows. The very notion is as gibberish as the square root of Tuesday.

Or put another way. We humans can’t look outside the domain of the human language game. But to the extent we pretend to look outside, then we’d have to admit that everything we do, think and say is literally as meaningless as a generative AI spewing out its word salad of 0s and 1s.

Of course that means everything I’ve written here is also just a story of my MPC. So to briefly recap my story for clarity: its narrative arc started with a particular scientific model of reality: the view that everything obeys the second law of thermodynamics. From there it followed that our thoughts and beliefs are at the end of a long chain of statistical prediction modeling that’s necessary in the moment to export entropy. The story then pondered “what does it all mean?” only to conclude that whatever we say it means, it’s our meaning. Looking outside to Platonic woo-woo land for transcendent meaning is just drinking more Kool-Aid flavored dopamine. That this entire story is also just a creation of my own statistical modeling is not a contradiction; it’s exactly the point.

As a final thought, and leaning into a future essay, it should be emphasized that none of this is meant as a post-modernist hell of “reality is all relative” or “any truth is as good as another”. No, not even close. In fact I will argue in said later essay for just the opposite. In the meantime, I don’t think a rational person’s cage should really be rattled by the view here. Dropping our metaphysical fantasies is certainly not a reason to throw up our hands and panic. Life doesn’t fall apart without a magic metaphysical “reality” anymore than it falls apart without sky gods or the illusion of free will. Biologist Richard Dawkins once famously said atheists “go one god further” in rejecting the magical thinking of religion. If the same atheists have the courage of their convictions, I believe they can also go one epistemological god further and reject the magical thinking of transcendent “reality”. Within the wonderful and beautiful scientific worldview that our human brains are capable of laying out, we can be sure of this: evolution made sure our scientific stories are generally stable and useful. And it gave us the tools to constantly improve on them.

And if there is something human civilization urgently needs to improve on, it’s the stories we tell. Dropping empty metaphysical fantasies about truth and reality is, I think, at least one small step along that way.

Footnotes:

(1) This example of Einstein objecting to quantum mechanics is, for me at least, a reminder of how our subconscious skill at the language game can fool us. And it’s somewhat ironic that he of all people fell for this trap. After all, his relativity theory is based precisely on a “Wittgenstein-like” approach to the language of physics. The Einstein that created relativity understood that words like space, time, mass and energy had no magic, transcendent meaning. They are meaningful only in their operational definitions, i.e. the way they are used.

(Note: this essay is a revised version of one of my postings of my Algorithmocene page on Medium)

I don’t understand what notions of meaning, truth, and reality you wish to debunk. You allow yourself to make numerous factual claims; so exactly what is it that you are denying?

The notion of truth and reality I wish to debunk is the denial that they’re human mental creations. My argument is a mild form of reductio ad absurdum. That is, I first make “factual” claims as if they’re independent of our mental creations. In particular, I take the current scientific worldview that entropy-exporting metabolism is the basis for life. That then leads to the conclusion that entropy-exporting (via predictive modeling) must therefore also be basis of the syntax and semantics of human language. Thus our notions of truth and reality, and whatever narratives and semantics we attach to them, must also be mental creations.

Note that this conclusion is generally considered unproblematic for basically all other human words (e.g. “beauty”, “pizza”, etc). I can think of no reason why “truth” and “reality” should get a special carve-out clause.

I still don’t understand. Suppose our notion of a pizza is in some sense a “mental creation”. What is the significance of that, in your argument? I don’t think you’re denying that pizzas exist.

Thanks for the questions.

You’re correct, I don’t deny pizzas exist. I don’t even deny that truth and reality exist. But I am arguing for what I believe is a more robust semantic model for the word “exist”. My point is that semantic models aren’t set in stone or fall from the sky; they’re necessarily human creations. In fact every human carries a slightly different semantic model for all our words, but we rarely notice it because our use of them normally coincides so well. That’s how we can all play Wittgenstein’s language game and feel we understand each other. (Which LLMs do as well, but in their case we have no idea what models they use).

One might think that, if their use coincides so well, who cares what semantic model is behind it all?But even in everyday life there are many, many cases where our human semantic models diverge. Even for seemingly unproblematic words like “exist”. For example, does a rainbow exist? What about the greatest singer of all time? Do the past and future exist? Or finally, back to the pizza: let’s say I drop it and the slices scatter on the floor—does it still exist?

These examples and many more illustrate, to me at least, that the canonical semantic model for “exist” (that is, a model that insists it somehow transcends human modeling) has too many failure modes to be serviceable (apart from it being principally incoherent).

On the other hand, a semantic model that simply accepts that all words and concepts are products of human modeling seems to me robustly unproblematic. But I can see I need to do a better job of spelling that out in my follow-up essay.

If the words and concepts are, it doesn’t follow that their referents are. “Moon” is a word we invented for something we didn’t invent. You can’t claim that the moon as such is a human invention any more than you can claim it is four letters long.

And note that there is not a single contrary theory on the lines of “human concepts are wholly caused and necessitated by the external non-mental world”. The contrary theory need be only that concepts can refer to non concepts. Are you familiar with the use/reference distinction? The concept of a pointer in programming?

Thanks again for your comments, they’re a great help. Hopefully my response below also addresses your other comments.

So yes, I’m familiar with the use/reference aka map/territory distinction. The latter is a very good way to phrase the issue here, so I’ll go with that nomenclature here.

Normally map v. territory is an extremely useful distinction that science has made fantastic progress with. But there are also well-known historical cases where it has been a conceptual trap. For example, Newton and Kant assumed that our “maps” of space and time are distinct from the “territory” of space and time. Einstein argued instead that they’re only meaningful through their operational definitions—i.e their maps. Only in dropping the distinction between map and territory here can one get to relativity theory. In quantum mechanics, at least in the Copenhagen interpretation, there is also no distinction between map and territory for physical observables. Even if one rejects the Copenhagen view, Heisenberg’s original insight came from treating physical observables as maps, not territory. To take a more mundane example: earlier cultures saw rainbows as territory; today we generally accept that rainbows, like faces in clouds, are only human maps.

If I may paraphrase what I take to be your view: your response to the above might be to say “yes, the face in the cloud is just a map, but the cloud itself is not. It is real territory regardless of my map.”

My response to that is: “Actually, what you refer to as ‘cloud’ is also just a map: namely, conceptual shorthand for a loose agglomerate of water vapor and other particles reflecting enough visible light to create a signal in your visual system. Your brain models that by mapping it all into ‘cloud’.”

Your response to that might be: “OK, even if ‘cloud’ is just a map, the water vapor and other particles are certainly real territory regardless of my map”

My response to that is: “Actually, water vapor and particulate matter are also just maps. ‘Water’ is a chemist’s map of a bound state of two hydrogen and one oxygen atom. Same goes for the other particulate matter. And we can continue like this: ‘atoms’ are physics shorthand for bound states of elementary particles, which are in turn shorthand for certain energy states of quantum fields, vibrating superstrings, or whatever the physics theory du jour claims they are.

My point is that every attempt to claim a thing as “real territory” always winds up being a human map. Even a broader claim like “It can’t all be maps. There must be some ‘real territory’ in a ‘world beyond’” is also a human mapping exercise. After all, we humans can only think and communicate with our human maps.

Whenever we distinguish between map and territory what we are doing is creating an internal model consisting of two parts: a “my maps” part and “the territory aka the world beyond” part. Again, that is usually a wonderfully helpful way to partition our maps, but, so I argue, not always.

In traditional philosophy, there’s a three way distinction between nominalism , conceptualism and realism. Those are three different theories in ended to explain three sets of issues: the existence of similarities, differences and kinds in the world, the territory; the way concept formation does and should work in humans; and issues to done with truth and meaning, relating the map and territory.

But conceptualism comes in two varieties.

One the one hand, there is is the theory that correct concepts “carve nature at the joints” or “identify clusters in thingspace”, the theory Aristotle and Ayn Rand. On the other hand is the “cookie cutter” theory, the idea that the categories are made by (and for) man, Kant’s “Copernican revolution”.

In the first approach, the world/territory is the determining factor, and the mind/map can do no better than reflect it accurately. In the second approach, the mind makes its own contribution.

Which is not to say that it’s all map, or that the mind is entirely in the driving seat. The idea that there is no territory implies solipsism (other people only exist in the territory, which doesn’t exist) and magic (changing the map changes the territory, or at least, future observations). Even if concepts are human constructions, the territory still has a role, which is determining the truth and validity of concepts. Even if the “horse” concept” is a human construct, it is more real than the “unicorn” concept. In cookie cutter terms, the territory supplies the dough, the map supplies the outline.

So Kantianism isn’t a completely idealistic or all-in-the-map philosophy...in Kant’s own terminology it’s empirical realism as well as transcendental idealism. I’s not as idealistic as Hegel’s system, for instance. Similarly, Aristoteleanism isn’t as realistic as Platonism—Plato holds that there aren’t just mind-independent conceits, but theyre in their own independent realm.

So, although the conceptualisms are different, they are both somewhere in the middle

And I’m saying it’s not a binary. Even if we use human made concepts to talk about the territory, we are still talking about the territory.

The point I’m trying to express (and clearly failing at) isn’t conceptualism or solipsism, at least not in the way my own semantic modeling interprets them. As I interpret them, the idealism of, say, Berkeley, Buddhism et al amounts to a re-branding of reality from being “out there” to “in my mind” (or “God’s mind”). I mean it differently, but because I refer constantly to our mental models, I can see why my argument looks a lot like that. Ironically, my failure may be a sort of illustration of the point itself. Namely, the limits of using language to discuss the limitations of language.

In fact, the point I’m trying to get to is not so much about “the nature of reality” but about the profound limitations of language. And that our semantic models tend to fool us into assigning a power to language that it doesn’t have. Specifically, we can’t use the language game to transcend the language game. Our theories of ontology and epistomology can’t coherently claim to refer to things beyond human language when these theories are wholly expressed in human language. Whatever model of reality we have, it’s still a model.

The objection of realism is that our models are not created in isolation, but by “actual reality” interacting with our modeling apparatus. My response is: that is a very useful way to model our modeling, but like all models, it has limitations. That is, I can make a mental model called “realism” in which there are mental models on the one hand and “real reality” on the other. I can further imagine the two interact in such a way that my models “carve reality at the joints”, or “identify clusters in thingspace”. But all of that is itself manifestly a mental model. So if I then want to coherently claim a particular model is more than just a model, I have to create a larger model in which the first model is imagined to be so. That can be fine as far as it goes. But realism – the claim of a “reality” independent of ANY model—commits one to an infinite nesting of mental models, each trying to escape their nature as mental models.

This situation is a close analog to the notion of “truth” in mathematics. Here the language game is explicitly limited to theorem-proving within formal systems. But we know there are unprovable statements within any formal system. So if I want a particular unprovable statement to count as “true”, I need a larger meta-system that makes it so. That’s fine as far as that goes. But to use the language game of formal systems to claim an unprovable statement is true independent of ANY proof, I would need an infinite nesting of meta-systems. That’s clearly incoherent, so when mathematicians want to claim “truth” in this way they have to exit the language game of formal systems – i.e. appeal to informal language and the philosophy of Platonism.

Personally I’m not a fan of Platonism, but it works as a philosophy of mathematics in so far as it passes the buck from formal to informal language. But that’s also where the buck stops. The sum of formal and informal language has no other system to appeal to, at least not one that can be expressed in language. To sum it all up with another metaphor: the semantic modeling behind the philosophy of realism overloads the word “reality” with more weight than the human language game can carry.

That’s your objection to solipsism. What’s your objection to conceptualism?

Who’s “us”? Some philosophers? All philosophers? Some laypeople? All laypeople?

Except that you just did. Well, you did in general. Theres a problem in referring to specific things behind our language. But who’s doing that? Kant isn’t. He keeps saying that the thing in itself is unknowable. So what’s the problem with Kantian conceptualism?

Whatever reality is, it’s still reality. You still haven’t said how the two are related.

A model of something real. “Is a model” doesn’t mean “is false”.

Does “more than a model” mean “true”?

I don’t see why. And if you reject realism, you have solipsism, which you also reject.

You can do that with larger systems, adding the theorem as an axiom, but you can also do that with different systems.

But that’s all rather beside the point… minimally realism requires some things to be true, and truth to be something to do with the territory.

Theres no reason why meaning and truth in maths have to work like meaning and truth in not-maths, or vice versa.

You need to notice the difference between truth and justifcation/proof. Truth, even realistic truth, is so easy to obtain that you can a certain amount by ransoming guessing. The tricky thing is knowing why it is true...justification.

This is bit of a side note but still may interesting: I suppose the history of scientific paradigm shifts can be framed as updates to our “map” v. “territory” partitions. A good scientific theory (in my account) is exactly what converts what was ostensibly “territory” into explicit mathematical models i.e. “maps”.

“Basis” is ambiguous. What makes language work causally, what makes it meaningful, where it is, and what makes it true, where it is, are different questions. If truth is a relationship between a living organism and a world beyond it , you can’t reduce it to just the metabolism of the organism, for instance.

Thanks for the comment. Honestly it took me a while to disambiguate (i.e. translate to myself what you’re getting at). So I take it as an interesting example of the point I was actually trying to make to Mitchell Porter previously. Namely, that our semantic models of normally unproblematic words can diverge quite a bit. E.g., my model for “truth” is not “a relationship between a living organism and a world beyond it”. Rather in my model, “the world beyond” is ultimately also part of our internal modeling. That’s because the very fact that we humans imagine and form narratives around “the world beyond” makes it per se a product of our internal models. Only magical thinking can escape this conclusion, but then we jettison the whole project of rationalism and science, imv.

BTW I do totally get how uncomfortable, frustrating and head-spinning this view is. But it wouldn’t be the first frustrating, head-spinning thing we’ve had to face about ourselves and “the world beyond”. Gödel’s Theorem, quantum mechanics and general relativity are all about head-spinning epistemic limitations. (That’s NOT to claim my little argument is on par with these illustrious examples!). But once we get used to them, they’re also a rich source of new scientific insights. In particular, I believe the view I argue for has quite serviceable benefits in that regard—at least it has for me. But I need to lay that out in another essay.

The word “beyond” *means” “not in our heads”. You’re just not respecting that.

It’s possible to put that in a non head spinning way: the world is the world and not in our heads; our thoughts about the world are in our heads.

It’s also possible to put it in a non head spinning way.

Many words can be used in an “in the head”/”on the map” way, and also in a “in the world”/”in the territory” way...and it’s also possible to disambiguate by using special phrases like “per se” and “as such” ..or “for me” and “in my view”. That way finger/moon confusions are avoided.

It’s unnecessarily uncomfortable, etc. If you simply keep track of whether you are using a word to a territory feature , or a map feature, the confusion vanishes.

Believing that you thought the world per se into existence is magical thinking!

Correct use of.language can remove conclusion. The “world per se” should refer to the territory , not our models of it. The phrase “per se” *means” “not in our heads”. You’re just not respecting that.

Perhaps I missed it in the wall of text, but I don’t think you got around to answering this? In fact, your second-to-last paragraph (“As a final thought...”) seems to be saying that this whole post was just preliminary to beginning on an answer.

Indeed, in a way that was my intention. In a coming essay I will try to lay out what I believe is a serviceable notion of truth and reality that we work with. The purpose of this first essay was to first lay out how much they are human creations.

I mean, the most ‘basic’ concepts that we use refer to our perceptions of things, it’s not “hopelessly circular” in that sense.

But sure, we reify ourselves.

Thanks for the feedback. If I understand you correctly, your point is the just one I intended to make.

Hey, I think you’ve got some insights and interesting questions in this post, though since you wrote it form Medium, stylistically it’s quite different from posts on LessWrong (which I think are much better for metaphysical philosophy). In order to get upvoted/read/engaged with, you might want to use the style around here.

For example phrases like “everyone knows” just feel a bit odd. Just talk about you believe to be true.

Hey, thanks for the feedback.

That’s entirely unconnected to understanding (if that were the case, a locked-in person who can only communicate by moving their eyes wouldn’t understand anything).

A locked-in person communicating only by eye movement would understand perfectly well in my account. If they’re alive, their metabolism keeps their body, brain and mind constantly interacting with their environment. This holds even if they’re asleep or in a coma. My point (which is really just orthodox biology) is that human language processing results from metabolic processes (what I’ve called model predictive controlling to highlight its modeling character), and that includes what we call syntax and semantics—our sense of “understanding”.

When asleep or in a coma, the mind doesn’t interact with the environment at all.

Also, this can’t be one of the requirements for understanding, because there is no conceptual connection between understanding something and interacting with the environment continuously (to the extent to which getting information through neural spikes can be approximated as continuous interaction with the environment) (rather than discretely).

Also, you can have an embodied language model that accepts information from the environment continuously (so that language model would then possess understanding).

That confuses causality with necessity (metabolism causally preceding understanding doesn’t mean that metabolism or continuous input are necessary for it).

I’m not sure if we’re talking past each other or if there is genuine disagreement, but I’ll expound a bit.

The sleeping/comatose mind does interact constantly with the environment in two ways. For starters, it’s well established that external sensory input (specifically sounds and touch) regularly makes its way into the conscious experience of dreaming and comatose state. But that’s just a side issue here. At a more fundamental level, every living thing interacts 24⁄7 with its environment through its metabolism.

Maybe this is the crux of a misunderstanding. I don’t claim that “continuous input” in the sense you (seem to) mean is necessary/causally antecedent to semantics. E.g., I’m not saying that I have to constantly look at a tree out in the woods in order to think about what a tree is. I’m only saying that any thought I have, and whatever language and semantics attached to it, are the result (causal/necessity if you like) of my metabolic processing. (Using metabolism in the broadest sense to mean any chemical pathways that use energy and produces entropy in the body, which includes neural activity). If that’s not the case, then something non-biological makes human language possible, which I assume you don’t intend. Either way, that would be a hypothesis for a different type of discussion forum.