I endorse and operate by Crocker’s rules.

I have not signed any agreements whose existence I cannot mention.

I endorse and operate by Crocker’s rules.

I have not signed any agreements whose existence I cannot mention.

“I’d add X to my priorities if I had 3x more time per day.” is not how I’d understand “X is my 3rd tier priority.”, so this would require additional explanation, whereas talking about it in terms of clones would require much less additional explanation.

Yeah, fair. “Nth serial clone’s priority”?

Maybe something with Harry Potter’s Time-Turner?

This seems oriented around modern examples, but I’d also be curious to hear pre-modern examples.

I thought that writing (as well as basic math) might technically fit your criteria, as it remained inaccessible to the majority for millennia, but maybe there weren’t really plenty of incentives to spread it, and/or the common folk would not have benefited from it that much, given everything else about the society at the time.

(Perhaps some ambitiously altruistic prince at some point tried to teach his peasants to write, but they were like “I don’t have time for this because I need to take care of my cows and my rice”.)

You can think about it in terms of clones, e.g. instead of “I’d do it if I had 2x more time”, you say “if I had a clone to have things done, the clone would do that thing” (equivalent in terms of work hours).

So you can say “that’s my 1st/2nd/3rd/nth clone’s priority”.

In which case, what they care about (their “actual” domain of utility/preference) is not [being in a specific city], but rather something more like “trajectories”.

I’m writing this mostly because I’m finding it horrifying that it appears the LessWrong consensus reality is treating “nonconsent” stuff as a cornerstone of how it views women.

Can you elaborate/give examples of this?

This post has also inspired some further thinking and conversations and refinement about the type of agency/consequentialism which I’m hoping to write up soon.

Did you end up publishing this?

(though this will probably be different in future rounds—SFF wants to

Looks like you cut off a part of the sentence.

There are some Ok options for getting tax-deductibility in the UK. I am still working on some ways for people in other European countries to get tax-deductibility.

Last year you had an arrangement with Effektiv Spenden. I wonder what happened that ES is not mentioned in this year’s post.

What do you mean by “ally” (in this context)?

IIRC Eric Schwitzgebel wrote something in a similar vein (not necessarily about LLMs, though he has been interested in this sort of stuff too, recently). I’m unable to dig out the most relevant reference atm but some related ones are:

https://faculty.ucr.edu/~eschwitz/SchwitzAbs/PragBel.htm

https://eschwitz.substack.com/p/the-fundamental-argument-for

https://faculty.ucr.edu/~eschwitz/SchwitzAbs/Snails.htm (relevant not because it talks about beliefs (I don’t recall it does) but because it argues for the possibility of an organism being “kinda-X” where X is a property that we tend to think is binary)

Also: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alief_(mental_state)

What’s SSD?

(Datapoint maybe of relevance, speaking as someone who figured that his motivation is too fear-driven and so recalled that this sequence exists and maybe is good for him to read to refactor something about his mind.)

Does that feel weird? For me it does—I feel a sense of internal resistance. A part of me says “if you believe this, you’ll stop trying to make your life better!” I think that part is kinda right, but also a little hyperactive.

It doesn’t feel weird to me at all. My first-order reaction is more like “sure, you can do it, and it can cause some sort of re-perspectivization, change in the level of gratitude, etc., but so what?”.

(Not disputing that changing the thresholds can have an effect on motivation.)

It seems to me like the core diff/crux between plex and Audrey is whether the Solution to the problem needs to take the form of

The top level of the system having some codified/crystallized values that protect the parts, leaving their agency plenty of room and optionality to flourish.

Some sort of decentralized but globally adaptive mycelium-like cooperation structure, where various components (communities, Kamis) act in just enough unison to prevent really bad outcomes and ensuring that we remain in a good basin.

Plex leans strongly towards “we need (1) and (2) is unstable”. Audrey leans at least moderately towards “(2) is viable, and if (2) is viable, then (2) is preferred over (1)”.

If I double click on this crux to get a crux upstream of it, I imagine something like:

How easy is it to screw over the world given a certain level of intelligence that we would expect from a bounded Kami-like system (+ some plausible affordances/optimization channels)?

Consequently:

How strong and/or centrally coordinated and/or uniformly imposed do the safeguards to prevent it need to be?[1]

And then:

What is the amount of “dark optimization power” (roughly, channels of influence that can be leveraged to achieve big outcomes, likely to be preferred by some sort of entity but that we (humans) are not aware of) that can be accessed by beings that we can expect to exist within the next decades?

This collapses a lot of complexity of potential solutions into three dimensions but just to convey the idea.

(FYI, I initially failed to parse this because I interpreted “‘believing in’ atoms” as something like “atoms of ‘believing in’”, presumably because the idea of “believing in” I got from your post was not something that you typically apply to atoms.)

Strongly normatively laden concepts tend to spread their scope, because (being allowed to) apply a strongly normatively laden concept can be used to one’s advantage. Or maybe more generally and mundanely, people like using “strong” language, which is a big part of why we have swearwords. (Related: Affeective Death Spirals.)[1]

(In many of the examples below, there are other factors driving the scope expansion, but I still think the general thing I’m pointing at is a major factor and likely the main factor.)

1. LGBT started as LGBT, but over time developed into LGBTQIA2S+.

2. Fascism initially denoted, well, fascism, but now it often means something vaguely like “politically more to the right than I am comfortable with”.

3. Racism initially denoted discrimination along the lines of, well, race, socially constructed category with some non-trivial rooting in biological/ethnic differences. Now jokes targeting a specific nationality or subnationality are often called “racist”, even if the person doing the joking is not “racially distinguishable” (in the old school sense) from the ones being joked about.

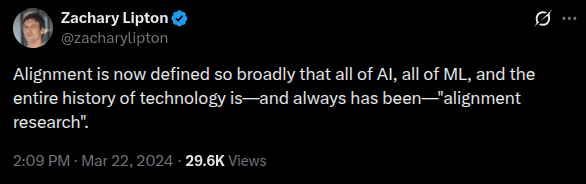

4. Alignment: In IABIED, the authors write:

The problem of making AIs want—and ultimately do—the exact, complicated things that humans want is a major facet of what’s known as the “AI alignment problem.” It’s what we had in mind when we were brainstorming terminology with the AI professor Stuart Russell back in 2014, and settled on the term “alignment.”

[Footnote:] In the years since, this term has been diluted: It has come to be an umbrella term that means many other things, mainly making sure an LLM never says anything that embarrasses its parent company.

See also: https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/p3aL6BwpbPhqxnayL/the-problem-with-the-word-alignment-1

https://x.com/zacharylipton/status/1771177444088685045 (h/t Gavin Leech)

5. AI Agents.

it would be good to deconflate the things that these days go as “AI agents” and “Agentic™ AI”, because it makes people think that the former are (close to being) examples of the latter. Perhaps we could rename the former to “AI actors” or something.

But it’s worse than that. I’ve witnessed an app generating a document with a single call to an LLMs (based on the inputs from a few textboxes, etc) being called an “agent”. Calling [an LLM-centered script running on your computer and doing stuff to your files or on the web, etc] an “AI agent” is defensible on the grounds of continuity with the old notion of software agent, but if a web scraper is an agent and a simple document generator is an agent, then what is the boundary (or gradient / fuzzy boundary) between agents and non-agents that justifies calling those two things agents but not a script meant to format a database?

There’s probably more stuff going on required to explain this comprehensively, but that’s probably >50% of it.

What’s your sample size?

Can you give a sample of those weird versions of AI safety?