My blog is here. You can subscribe for new posts there.

My personal site is here.

My X/Twitter is here

You can contact me using this form.

My blog is here. You can subscribe for new posts there.

My personal site is here.

My X/Twitter is here

You can contact me using this form.

I am obviously not the creator; I have not worked at a frontier lab (as you can verify through online stalkery if you must). (I also have not even read Demons, but that’s harder to verify)

I think I first saw this through the highly-viewed Tim Hwang tweet, but also have had several people in-person mention it to me. I am not on Reddit at all.

The microsites that stand out to me are Gradual Disempowerment, Situational Awareness, and (this one is half my fault) the Intelligence Curse. It’s not a large set. Gradual Disempowerment talks about cultural and psychological in the abstract and as affected by future AIs, but not concretely analyzing the current cultural & social state of the field. I don’t remember seeing a substantive cultural/psychological/social critique of the AGI uniparty before. I think this alone justifies that statement.

You are obviously not in the AGI uniparty (e.g. you chose to leave despite great financial cost).

Basically I think it’s pretty accurate at describing the part of the community that inhabits and is closely entangled with the AI companies, but inaccurate at describing e.g. MIRI or AIFP or most of the orgs in Constellation, or FLI or … etc.

I agree with most of these, though my vague sense is some Constellation orgs are quite entangled with Anthropic (e.g. sending people to Anthropic, Anthropic safety teams coworking there, etc.), and Anthropic seems like the cultural core of the AGI uniparty.

They don’t name it. This is my inference based on Googling

I think this is a good and important post, that was influential in the discourse, and that people keep misunderstanding.

What did people engage with? Mostly stuff about whether saving money is a good strategy for an individual to prepare for AGI (whether for selfish or impact reasons), human/human inequality, and how bad human/human inequality is on utilitarian grounds. Many of these points were individually good, but felt tangential to me.

But none of that is what I was centrally writing about. Here is what I wrote about instead:

Power. The world’s institutions are a product of many things, including culture and inertia, but a big chunk is also selection for those institutions that are best at accumulating power, and then those institutions that get selected for wielding their power for their ends. If the game changes due to technology (especially as radical as AGI), the strategy changes. Currently the winning strategy is rather fortunate for most people, since it encourages things like prosperity & education, and creates pressures towards democracy. On the other hand, the default vision of AGI explicitly sets out to render people powerless, and therefore useless to Power. This will make good treatment of the vast majority of humanity far more contingent:

Adam Smith could write that his dinner doesn’t depend on the benevolence of the butcher or the brewer or the baker. The classical liberal today can credibly claim that the arc of history really does bend towards freedom and plenty for all, not out of the benevolence of the state, but because of the incentives of capitalism and geopolitics. But after labour-replacing AI, this will no longer be true. If the arc of history keeps bending towards freedom and plenty, it will do so only out of the benevolence of the state (or the AI plutocrats) [EDIT: or, I obviously should’ve explicitly written out, if we have a machine-god singleton that enforces, though I would fold this into “state”, just an AI one]. If so, we better lock in that benevolence while we have leverage—and have a good reason why we expect it to stand the test of time.

Ambition. Much change in the world, and much that is great about the human experience, comes from ambition. I go through the general routes to changing the world, from entrepreneurship to science to being An Intellectual™ to politics to religion to even military conquest, and point out that full AGI makes all of those harder. Ambition having outlier impacts is the biggest tool that human labor has for shifting the world in ways that are different from the grinding out of material incentives or the vested interests that already have capital (or, as I neglected to mention, offices). Also, can’t you just feel it?

Dynamism & progress. We, presumably, want cultural, social & moral progress to continue. How does that progress come about? Often, because someone comes from below and challenges whoever is currently on top. This requires the possibility of someone winning against those at the top. Or, to take another tack: (and this is not even implicitly in the post since I hadn’t yet articulated this a year ago, though the vibe is there) historically, the longer a certain social state of affairs is kept in place, the more participants in it goodhart for whatever the quirks of the incentive structure are. So far, this goodharting has been limited by the fact that if you goodhart hard enough, your civilization collapses at the political and economic as well as cultural level, and is invaded, and the new invaders bring some new incentive game with them. But if an AI-run economy and power concentration prevent the part where civilization collapses and is invaded, it seems possible for the political & economic collapse to be forestalled indefinitely, and the cultural collapse / goodharting / stagnation to get indefinitely bad. Or to take yet another tack: isn’t this dynamism thing the point of Western civilization? I admit that I don’t have a general theory of why I feel like shouting “BUT DYNAMISM! BUT PROGRESS!” at any locked-in vision of the future, but, as the spirit commands it, I will continue shouting it.

Some of the big questions:

How true are the selectionist accounts of why modern institutions tend towards niceness, and under which AGI scenarios are these accounts true or false?

What is it that makes a culture alive, dynamic, and progress-driving, and how does this relate to questions about material conditions and the distribution of power?

… and I have to admit, man, these are tough questions! If you want a solution, maybe get back to me next year. (I also think these cruxes cannot be rounded to just e.g. takeoff speeds, or other technical factors; there are also a lot of thorny questions about culture, economics, (geo)politics, human psychology, and moral philosophy that matter for these questions regardless of (aligned) AI outcomes.)

What do I wish I had emphasized more? I really did not want people to read this and go accumulate capital at AGI labs or quant finance, as I wrote at the top of the takeaways section. I wish I had emphasized more this thing, which Scott Alexander recently also said:

But don’t waste this amazing opportunity you’ve been given on a vapid attempt to “escape the permanent underclass”.

Another underrated point is inter-state inequality (Anton Leicht has discussed this e.g. here, but is the only person I know thinking seriously about it). Non-US/China survival strategies for AGI remain neglected! I go through potential ramifications of current trends towards the end of this post.

The Substack version was called “Capital, AGI, and human ambition”, which I think was a clearer title and might’ve prevented focus on capital and its (personal) importance. “AGI entrenches capital and reduces dynamism in society” might’ve been a better title than either—though I do think “human ambition” belongs in the title.)

Scott Alexander’s post on It’s Still Easier To Imagine The End Of The World Than The End Of Capitalism is valuable for pointing out that the space of possibilities is large. I have been meaning to write a response to this, and also some related work from Beren & Christiano, for a long time.

“Yudkowskianism” is a Thing (and importantly, not just equivalent to “rationality”, even in the Sequences sense). As I write in this post, I think Yudkowsky is so far the this century’s most important philosopher and Planecrash is the most explicit statement of his philosophy. I will ignore the many non-Yud-philosophy parts of Planecrash in this review of my review, partly because the philosophy is what I was really writing about, and partly to avoid mentioning the mild fiction-crush I had on Carissa.

There is a lot of discussion within the Yudkowskian frame. There is also a lot of failure to engage with it from outside. There is also (and I think this is greatly under-appreciated) a lot of discussion across AI safety & the rationality community, from people who have a somewhat fish-in-the-water relation to Yudkowskianism. Consciously, they consider themselves to be distanced from it, having retreat from pure Yudkowskianism to something they think is more balanced and reasonable. I think these people should become more aware of their situation, since they lack the deep internal coherence of Yudkowskianism, while often still holding on to some of the certainty and rigidity that comes with it. I hope my post has done its bit here.

Perhaps strangely, the longest section of my review is on the political philosophy of dath ilan. I think this is something where Yudkowsky is underrated. A clear-eyed view of incentives & economics is very rare, and combined with Yudkowsky’s humanism, I like the results. Governance sci-fi is criminally neglected, outside Planecrash, Robin Hanson, and the occasional book like Radical Markets. (It’s also interesting that Nate Soares tells his story of working on reforming our civilization’s governance, and building a rationality curriculum to that end, only to in the process of research for that stumble across The Sequences, “halt, melt, and catch fire”, and then pivot to alignment. I wonder if all rationalist-y governance-idealists end up pivoting, or if there are many such people in government but they just don’t achieve much.)

And is he right about, y’know, all of it? Look, I read some Feyerabend this year, and a bunch of Berlin, and my anarchist/pluralist tendencies regarding epistemics got worse. My attitude towards worldviews has always been more fox than hedgehog, and I think most people have insufficiently broad distributions (in particular due to only taking into account in-paradigm issues). I still agree with what I wrote in my review: often a great frame, and lots of genuine insights, and a big part of my own worldview, but not yet a scientific theory. To the extent that it’s a theory, it’s more like a theory in macroeconomics than a theory in physics: it sometimes gives coherent predictions, but it’s not like you can turn a crank and trace the motion of particles, and likely that the course of events will eventually demand a new theory. As with many paradigms, depending on how you view it, the empirical flaws range from minor details to most of the world. Part of me also thinks it’s too neat, but perhaps this is partly romantic pining for the undiscovered. There is a chance I later come back and shake my head at my youthful folly of trying to think outside the box despite having the answers laid out for me (except that in such a world I expect to be dead from the AIs). But in my modal world Yudkowskianism ends up one of the big philosophical stepping stones on a never-ending path, right about much but later reframed & corrected. What I wrote about Yudkowskanism’s edifice-like nature, impressive scope & coherence, and claim to be a “system of the world”, are all things I still endorse, and which I hope this review helped make clearer.

I feel like I should make some call for more cross-paradigm communication and debate. And I really appreciate people like @Richard_Ngo going out and thinking the big thoughts—I wish we had more people like that—or Yudkowsky making his case in podcasts and books. But also, I think it’s often hard and very abstract to argue about paradigms. A lot of people talk past each other due to different assumptions and worldviews. I expect we’ll be collectively in a state of uncertainty, apart from the hedgehogs (non-pejorative!) who are very confident in one view, and then eventually some hedgehog faction or mix of them will be proven right, or all of them will be proven wrong and it’ll be something unexpected. The messiness is part of the process, and I expect we do have to wait for Reality to give us more bits and Time to wield its axe, rather than being able to settle it all with a few more posts, podcasts, or MIRI dialogues.

Also: given Yudkowsky’s own choice of formats, I consider it my homage to him that my most direct discussion of his philosophical project does not happen in “Yudkowskianism Explained: The Four Core Ideas”, but in the 2nd half of a review of his BDSM decision theory fanfic.

I continue to like this post. I think it’s a good joke, hopefully helps make more sticky in people’s minds what muddling through is, and manages some good satirical sociopolitical worldbuilding. However, I admit in the category of satirical AI risk fiction it has been beaten by @Tomás B. ’s The Company Man , and it contains less insight than A Disneyland Without Children

In retrospect, I think this was a good and thorough paper, and situational awareness concerns have become more prevalent over time. If I could go back in time, I would focus much more on the stages -type tasks, which are important for eval awareness, which is now a big concern about the validity of many evals as models are smarter, and where I think much more could’ve been done (e.g. Sanyu Rajakumar investigated a bit further). As usual, most of the value in any area is concentrated in a small part of it.

I agree the AI safety field in general vastly undervalues building things, especially compared to winning intellectual status ladders (e.g. LessWrong posting, passing the Anthropic recruiting funnel, etc.).

However, as I’ve written before:

[...] the real value of doing things that are startup-like comes from [...] creating new things, rather than scaling existing things [...]

If you want to do interpretability research in the standard paradigm, Goodfire exists. If you want to do evals, METR exists. Now, new types of evals are valuable (e.g. Andon Labs & vending bench). And maybe there’s some interp paradigm that offers a breakthrough.

But why found? Because there is a problem where everyone else is dropping the ball, so there is no existing machine where you can turn the crank and get results towards that problem.

Now of course I have my opinions on where exactly everyone else is dropping the ball. But no doubt there are other things as well.

To pick up the balls, you don’t start the 5th evals company or the 4th interp lab. My worry is that that’s what all the steps listed in “How to be a founder” point towards. Incubators, circulating pitches, asking for feedback on ideas, applying to RFPs, talking to VCs—all of these are incredibly externally-directed, non-object-level, meta things. Distilling the zeitgeist. If a ball is dropped, it is usually because people don’t see that it is dropped, and you will not discover the dropedness by going around asking “hey what ball is dropped that the ecosystem is not realizing?”. You cannot crowdsource the idea.

This relates to another failure of AI safety culture: insufficient and bad strategic thinking, and a narrowmindedness over the solutions. “Not enough building” and “not enough strategy/ideas” sound opposed, when you put them on some sort of academic v doer spectrum. But the real spectrum is whether you’re winning or not, and “a lack of progress because everyone is turning the same few cranks and concrete building towards the goal is not happening” and “the existing types of large-scale efforts are wrong or insufficient” are, in a way, related failure modes.

Also, of course, beware of the skulls. “A frontier lab pursuing superintelligence, except actually good, this time, because we are trustworthy people and will totally use our power to take over the world for only good”

One quick minor reaction is that I don’t think you need IC stuff for coups. To give a not very plausible but clear example: a company has a giant intelligence explosion and then can make its own nanobots to take over the world. Doesn’t require broad automation, incentives for governments to serve their people to change, etc

I’d argue that the incentives for governments to serve their people do in fact change given the nanobots, and that’s a significant part of why the radical AGI+nanotech leads to bad outcomes in this scenario.

Imagine two technologies:

Auto-nanobots: autonomous nanobot cloud controlled by an AGI, does not benefit from human intervention

Helper-nanobots: a nanobot cloud whose effectiveness scales with human management hours spent steering it

Imagine Anthropenmind builds one or the other type of nanobot and then decides whether to take over the world and subjugate everyone else under their iron fist. In the former case, their incentive is to take over the world, paperclips their employees & then everyone else, etc. etc. In the latter case, the more human management they get, the more powerful they are, so their incentive is to get a lot of humans involved, and share proceeds with them, and the humans have leverage. Even if in both cases the tech is enormously powerful and could be used tremendously destructively, the thing that results in the bad outcome is the incentives flipping from cooperating with the rest of humanity to defecting against the rest of humanity, which in turn comes about because the returns to those in power of humans go down.

(Now of course: even with helper-nanobots, why doesn’t Anthropenmind use its hard power to do a small but decapitating coup against the government, and then force everyone to work as nanobot managers? Empirically, having a more liberal society seems better than the alternative; theoretically, unforced labor is more motivated, cooperation means you don’t need to monitor for defection, principle-agent problems bite hard, not needing top-down control means you can organize along more bottom-up structures that better use local information, etc.)

Maybe helpful to distinguish between:

“Narrow” intelligence curse: the specific story where selection & incentive pressures by the powerful given labor-replacing AI disempowers a lot of people over time. (And of course, emphasizing this scenario is the most distinct part of The Intelligence Curse as a piece compared to AI-Enabled Coups)

“Broad” intelligence curse: severing the link between power and people is bad, for reasons including the systemic incentives story, but also because it incentivizes coups and generally disempowers people.

Now, is the latter the most helpful place to draw the boundary between the category definitions? Maybe not—it’s very general. But the power/people link severance is a lot of my concern and therefore I find it helpful to refer to it with one term. (And note that even the broader definition of IC still excludes some of GD as the diagram makes clear, so it does narrow it down)

Curious for your thoughts on this!

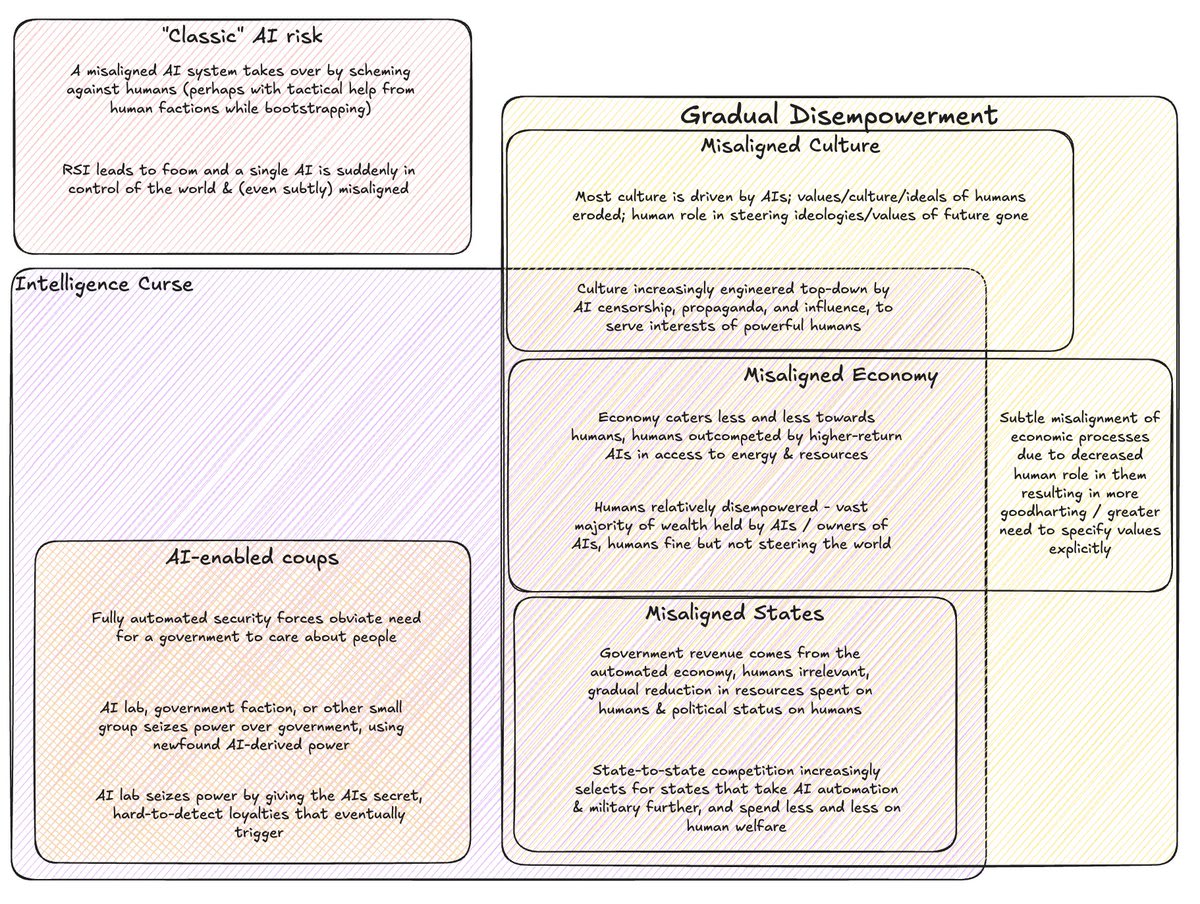

Noting that your 2x2 is not exactly how I see it. For example, power grabs become more likely due to the intelligence curse and humans being more able to attempt them is a consequence of the gradual incentives, and (as you mention above) parts of gradual disempowerment are explicitly about states becoming less responsive to humans due to incentives (which, in addition to empowering some AIs, will likely empower humans who control states).

My own diagram to try to make sense of these is here (though note that this is rough OTOH work, not intended as , and not checekd with authors of the other pieces):

Thanks, this was excellent!

To summarize, for anyone else reading this, the model proposed is essentially:

The most fundamental and primitive system for choosing a ruler/government is war, in which the strong win

Wars are very expensive, so all sides have an incentive to avoid them

However, if you setup some layer above the raw physical conflict to decide the winner, the loser has to calculate that resorting to war wouldn’t go well for them either. Therefore, the higher layer has to be legibly predictive of the lower layer.

Therefore, democracy arises when the number of people on a side is a good predictor of the outcome of a conflict, which is true under industrialized warfare that relies on massive production & large armies.

Of course, there’s a lot of lag in these things, so e.g. even though nuclear weapons change the above, they haven’t been used and systems have inertia. (Also, implicitly, Japan—the review’s main topic—had enough inertia from the samurai ruling class to current bureaucrats that real power still resides with them).

One story for why technocratic, elite-driven governance is becoming more common (but is it? see below) is that success in conflict would now rely more on the highly-educated, information control, and so forth

One story for the future trend is that offense becomes easier with drones etc., so assassination will become easier and easier, so victory in power struggles will come down to secrecy & ruling from the shadows, so MITI-style technocratic cabal governance might become even more common.

OTOH, some comments/questions that come to mind:

This is all effectively a story of internal selection within a country. However, times and places differ in the extent to which the main pressure on the political system is an internal or external threat. Now, winning wars against external adversaries is pretty similar to winning wars against internal ones, so with state-to-state competition in the industrial age. But was it internal or external competition that actually provided the bits of selection? (My guess is that in stable countries, it’s more the external selection that promotes democracies—e.g. the UK is just remarkably stable and an armed revolt of a losing political faction doesn’t seem like it’s been in the cards in the last few centuries) In general, this focus on internal rather than external competition seems like a very American focus, thanks to America’s geographic luck & (waning) hegemonic position.

What’s the relative importance of army size & mass production in military tech over time? E.g. are the Napoleonic Wars more like WW1 or more like feudal times, in terms of what it takes to win? If the latter, it seems like US & UK democratization can’t really be downstream.

Is part of this forward luck, rather than causation? E.g. you could tell a story where the UK & US democratized for circumstantial internal reasons, but then this made them more stable & effective internally, and helped them win externally. I.e. it’s not that countries drift towards the optimum, but that countries are at many different fitness points and do not even reliably drift towards higher fitness, but then selection prunes the ranks and rewards the fittest. In general, I think many explanations like this emphasize the causal chain more than the luck + selection.

Isn’t the growth of bureaucracy as a natural part of the lifecycle of institutions a more natural story for decreasing representativeness?

And, come to mention, are Western governments becoming less representative of the popular will over time at all? It seems like the best argument for this being true is that in the past few years, educational polarization means that elite & non-elite views on some issues (esp. immigration) are further apart than usual. But this is a very recent trend, and the elites are losing this one! In many ways, the elite held more leverage before the internet decentralized media. To the extent that Western governments are less able to deliver the goods that the population demands, this seems less because they’re taken over by elites with different interests to the voters, and more because of (1) broad demographic & economic trends, (2) voters having preferences that make these hard to fix (e.g. can’t raise retirement ages to fix #1; can’t increase immigration to mitigate the need to reduce the retirement age less; can’t build much nuclear power) and these voters very successfully forcing the political system to avoid taking elite-recommended actions (cf. French retirement age debate), and (3) general institutional & cultural decay and dysfunction. Now of course, part of #3 is bureaucratic capture etc., but a lot of the value capture is also by non-technocratic-elite groups (e.g. NIMBYs, pensioners, landlords).

There’s a version now that was audited by Chrome Web Store, if that’s enough for you: https://chromewebstore.google.com/detail/objective/dckljlpogfgmgmnbaicaiohioinipbge?authuser=0&hl=en-GB

Currently you need to be on the beta list though, since it costs Gemini API credits to run (though a quite trivial amount)—if you (or anyone else) DMs me an email I can add you to the list, and at some point if I have time I might enable payments such that it’s generally available.

Thanks a lot for this post! I appreciate you taking the time to engage, I think your recommendations are good, and I agree with most of what you say. Some comments below.

“the intelligence curse” or “gradual disempowerment”—concerns that most humans would end up disempowered (or even dying) because their labor is no longer valuable.

The intelligence curse and GD are not equivalent. In particular, I expect @Jan_Kulveit & co. would see GD as a broader bucket including also various subtle forms of cultural misalignment (which tbc I think also matter!), whereas IC is more specifically about things downstream of economic (and hard power, and political power) incentives. (And I would see e.g. @Tom Davidson’s AI-enabled coup risk work as a subset of IC, as representing the most sudden and dramatic way that IC incentives could play out)

It’s worth noting I doubt that these threats would result in huge casualty counts (due to e.g. starvation) or disempowerment of all humans (though substantial concentration of power among a smaller group of humans seems quite plausible).

[fn:]

That said, I do think that technical misalignment issues are pretty likely to disempower all humans and I think war, terrorism, or accidental release of homicidal bioweapons could kill many. That’s why I focus on misalignment risks.

I think if you follow the arguments, disempowerment of all humans is plausible, and disempowerment of the vast majority even more so. I agree that technical misalignment is more likely to lead to high casualty counts if it happens (and I think the technical misalignment --> x-risk pathway is possible and incredibly urgent to make progress on).

I think there’s also a difference between working on mitigating very clear sequences of steps that lead to catastrophe (e.g. X --> Y --> everyone drops dead), and working on maintaining the basic premises that make things not broken (e.g. for the last 200 years when things have been getting much better, the incentives of power and humans have been remarkably correlated, and maybe we should try to not decorrelate them). The first is more obvious, but I think you should also be able to admit theories of change of the second type at least sufficiently that, for example, you would’ve decided to resist communism in the 1950s (“freedom good” is vague, and there wasn’t yet consensus that market-based economies would provide better living standards in the long run, but it was still correct to bet against the communists if you cared about human welfare! basic liberalism is very powerful!).

Mandatory interoperability for alignment and fine-tuning is a great idea that I’m not sure I’ve heard before!

Alignment to the user is also a great idea (which @lukedrago & I also wrote about in The Intelligence Curse). There are various reasons I think the per-user alignment needs to be quite fine-grained (e.g. I expect it requires finetuning / RLHF, not just basic prompting), which I think you also buy (?), and which I hope to write about more later.

Implicit in my views is that the problem would be mostly resolved if people had aligned AI representatives which helped them wield their (current) power effectively.

Yep, this is a big part of the future I’m excited to build towards.

I’m skeptical of generally diffusing AI into the economy, working on systems for assisting humans, and generally uplifting human capabilities. This might help some with societal awareness, but doesn’t seem like a particularly leveraged intervention for this. Things like emulated minds and highly advanced BCIs might help with misalignment, but otherwise seems worse than AI representatives (which aren’t backdoored and don’t have secret loyalties/biases).

I think there are two basic factors that affect uplift chances:

Takeoff speed—if this is fast, then uplift matters less. However, note that there are two distinct ways in which time helps:

more societal awareness over time and more time to figure out what policies to advocate and what steps to take and so on—and the value of this degrades very quickly with takeoff speed increasing

people have more power going into the extreme part of takeoff—but note that how rapidly you can ramp up power also increases with takeoff speed (e.g. if you can achieve huge things in the last year of human labor because of AI uplift, you’re in a better position when going into the singularity, and the AI uplift amount is related to takeoff speed)

How contingent is progress along the tech tree. I believe:

The current race towards agentic AGI in particular is much more like 50% cultural/path-dependent than 5% cultural/path-dependent and 95% obvious. I think the decisions of the major labs are significantly influenced by particular beliefs about AGI & timelines; while these are likely (at least directionally) true beliefs, it’s not at all clear to me that the industry would’ve been this “situationally aware” in alternative timelines.

Tech progress, especially on fuzzier / less-technical things about human-machine interaction and social processes, is really quite contingent. I think we’d have much meaningfully worse computer interfaces today if Steve Jobs had never lived.

(More fundamentally, there’s also the question of how high you think human/AI complementarity at cognitive skills to be—right now it’s surprisingly high IMO)

I’m skeptical that local data is important.

I’m curious what your take on the basic Hayek point is?

I agree that AI enabled contracts, AI enabled coordination, and AIs speeding up key government processes would be good (to preserve some version of rule of law such that hard power is less important). It seems tricky to advance this now.

I expect a track record of trying out some form of coordination at scale is really helpful for later getting it into government / into use by more “serious” actors. I think it’s plausible that it’s really hard to get governments to try any new coordination or governance mechanism before it’s too late, but if you wanted to increase the odds, I think you should just very clearly be trying them out in practice.

Understanding agency, civilizational social processes, and how you could do “civilizational alignment” seems relatively hard and single-single aligned AI advisors/representatives could study these areas as needed (coordinating research funding across many people as needed).

I agree these are hard, and also like an area where it’s unclear if cracking R&D automation to the point where we can hill-climb on ML performance metrics gets you AI that does non-fake work on these questions. I really want very good AI representatives that are very carefully aligned to individual people if we’re going to have the AIs work on this.

We mention the threat of coups—and Davidson et. al.’s paper on it—several times.

Regarding the weakness or slow-actingness of economic effects: it is true that the fundamental thing that forces the economic incentives to percolate to the surface and actually have an effect is selection pressure, and selection pressure is often slow-acting. However: remember that the time that matters is not necessarily calendar time.

Most basically, the faster the rate of progress and change, the faster selection pressures operate.

As MacInnes et. al. point out in Anarchy as Architect, the effects of selection pressures often don’t manifest for a long time, but then appear suddenly in times of crisis—for example, the World Wars leading to a bunch of industrialization-derived state structure changes happening very quickly. The more you believe that takeoff will be chaotic and involve crises and tests of institutional capacity, the more you should believe that unconscious selection pressures will operate quickly.

You don’t need to wait for unconscious selection to work, if the agents in charge of powerful actors can themselves plan and see the writing on the wall. And the more planning capacity you add into the world (a default consequence of AI!), the more effectively you should expect competing agents (that do not coordinate) to converge on the efficient outcome.

Of course, it’s true that if takeoff is fast enough then you might get a singleton and different strategies apply—though of course singletons (whether human organizations or AIs) immediately create vast risk if they’re misaligned. And if you have enough coordination, then you can in fact avoid selection pressures (but a world with such effective coordination seems to be quite an alien world from ours or any that historically existed, and unlikely to be achieved in the short time remaining until powerful AI arrives, unless some incredibly powerful AI-enabled coordination tech arrives quickly). But this requires not just coordination, but coordination between well-intentioned actors who are not corrupted by power. If you enable perfect coordination between, say, the US and Chinese government, you might just get a dual oligarchy controlling the world and ruling over everyone else, rather than a good lightcone.

If humanity loses control and it’s not due to misaligned AI, it’s much more likely to be due to an AI enabled coup, AI propaganda or AI enabled lobbying than humans having insufficient economic power.

AI-enabled coups and AI-enabled lobbying all get majorly easier and more effective the more humanity’s economic role have been erased. Fixing them is also all part of maintaining the balance of power in society.

I agree that AI propaganda, and more generally AI threats to the information environment & culture, are a big & different deal that intelligence-curse.ai don’t address except in passing. You can see the culture section of Gradual Disempowerment (by @Jan_Kulveit @Raymond D & co.) for more on this.

There’s a saying “when all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail” that I think applies here. I’m bearish on [approaches] opposed to multi-disciplinary approaches that don’t artificially inflate particular factors.

I share the exact same sentiment, but for me it applies in reverse. Much “basic” alignment discourse seems to admit exactly two fields—technical machine learning and consequentialist moral philosophy—while sweeping aside considerations about economics, game theory, politics, social changes, institutional design, culture, and generally the lessons of history. A big part of what intelligence-curse.ai tries to do is take this more holistic approach, though of course it can’t focus on everything, and in particular neglects the culture / info environment / memetics side. Things that try to be even more holistic are my scenario and Gradual Disempowerment.

I don’t believe the standard story of the resource curse.

What do you think is the correct story for the resource curse?

I find the scenario implausible.

This is not a scenario, it is a class of concerns about the balance of power and economic misalignment that we expect to be a force in many specific scenarios. My actual scenario is here.

The “social-freeze and mass-unemployment” narrative seems to assume that AI progress will halt exactly at the point where AI can do every job but is still somehow not dangerous.

We do not assume AI progress halts at that point. We say several times that we expect AIs to keep improving. They will take the jobs, and they will keep on improving beyond that. The jobs do not come back if the AI gets even smarter. We also have an entire section dedicated to mitigating the risks of AIs that are dangerous, because we believe that is a real and important threat.

More directly, full automation of the economy would mean that AI can perform every task in companies already capable of creating military, chemical, or biological threats. If the entire economy is automated, AI must already be dangerously capable.

Exactly!

I expect reality to be much more dynamic, with many parties simultaneously pushing for ever-smarter AI while understanding very little about its internals.

“Reality will be dynamic, with many parties simultaneously pushing for ever-smarter AI [and their own power & benefit] while understanding very little about [AI] internals [or long-term societal consequences]” is something I think we both agree with.

I expect that approaching superintelligence without any deeper understanding of the internal cognition this way will give us systems that we cannot control and that will get rid of us. For these reasons, I have trouble worrying about job replacement.

If we hit misaligned superintelligence in 2027 and all die as a result, then job replacement, long-run trends of gradual disempowerment, and the increased chances of human coup risks indeed do not come to pass. However, if we don’t hit misaligned superintelligence immediately, and instead some humans pull a coup with the AIs, or the advanced AIs obsolete humans very quickly (very plausible if you think AI progress will be fast!) and the world is now states battling against each other with increasingly dangerous AIs while feeling little need to care for collateral damage to humans, then it sure will have been a low dignity move from humanity if literally no one worked on those threat models!

You also seem to avoid mentioning the extinction risk in this text.

The audience is primarily not LessWrong, and the arguments for working on alignment & hardening go through based on merely catastrophic risks (which we do mention many times). Also, the series is already enough of an everything-bagel as it is.

Fair, I should’ve mentioned this. I speculated about this on Twitter yesterday. I also found the prose somewhat off-putting. Will edit to mention.