Note: this is from my personal blog here.

A strange phenomenon plagues public discourse. Subtle and largely detached from the culture war, it often manages to evade detection. Can you spot it in each of the following arguments or discussion points?

Drugs like cocaine and heroin are bad. They are ruinous to users’ health, and use imposes a large negative externality on society.

We should decriminalize drugs. There is no reason to tear families apart and ruin lives for the sake of regulating consciousness.

Most American adults should exercise more. Exercise has a plethora of mental and physical health benefits, after all, and most adults are sedentary.

This expansion of unemployment insurance is bad. It creates distortionary incentives and will reduce workforce participation.

All four arguments completely ignore the first-order, direct effects of the practice in question!

Drug use and the war on drugs might impose serious costs on society, but we can’t forget that drugs themselves are fun to use! Exercise may be very important to personal wellbeing, but don’t ignore that (for some people, some of the time) exercise sucks! And we can talk about the second-order consequences of any sort of social welfare program, but let’s not neglect that the money directly improves poor people’s lives!

Saying this out loud sounds trivial, almost stupid. But I think “first-order effect neglect,” as I’ll call it, is a serious issue with public discourse.

When was the last time…

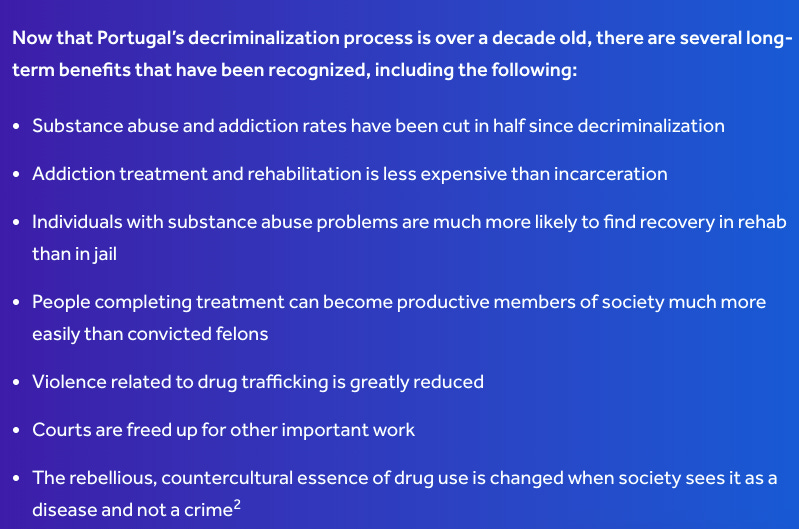

When was the last time that you heard a debate over the merits of drug legalization consider the stupidly-obvious fact that drugs make people happy? I don’t know if I ever have! Consider this list from the first result of my Google search for “pros and cons drug decriminalization.”

These are all valid and important points to consider, but nowhere is a mention of the most direct and obvious effect of drug use: if 10% more people smoke weed because of decriminalization, that’s a lot in chemical-induced pleasure!

Some public discussions have only a mild case of the disease. Consider Biden’s COVID relief package, as well as the larger discourse about public assistance in America. I’m sure there are better examples, but I managed to find this tweet pretty quickly.

As an observer of the online liberal-technocrat-effective altruism nexus, I see points like this made on Twitter or elsewhere from time to time. But—as the tweet’s sarcastic tone indicates—the Discourse too often neglects the simple, obvious, and direct positive impacts of giving people money.

Am I being unfair? Take a look at this list from the first result of my Google search for “pros and cons of basic income”

At the risk of beating a dead horse, there is no mention of the fact that money makes people better off, so giving them money is good. This is sort of gestured at in the second benefit listed, “people would have the freedom to return to school or stay home to care for a relative,” but even this point associates the benefit with doing something economically productive (education) or helping someone other than the recipient (caring for a relative). Nowhere on the list does it say “people can now buy things they like.”

What’s going on?

It is important to note that “first-order effect neglect” of some policy or idea is by no means limited to that idea’s opponents. In other words, it can’t be explained solely by ideological incentives. So, what are some other possible explanations?

1. Fish in water (or humans in air)

For one thing, first order effects might seem so obvious that explicit recognition would appear awkward or forced. The “water we swim in” analogy isn’t perfect, since fish (presumably) don’t have any concept of water.

Humans, though, have an understanding of air. We implicitly know that we’re surrounded by a gaseous mix of some sort even when we are not explicitly considering the fact. Nonetheless, it requires some sort of unusual stimulus to regard the air as a thing in and of itself. Ask someone to enumerate the things in a room, and “air” will likely fail to make the list. Even when the air is a vehicle for some physical sensation, such as cold, we still may think of “cold” itself as the relevant object itself instead of as a property of the air.

I think this likely explains a lot of the problem. First-order effects are the air we walk in. Of course drugs feel good. Of course exercise is hard. You don’t need to tell me that.

But banality can beget its own destruction. When everyone knows (or simply believes) that everyone else knows something (who in turn know that everyone else knows, ad infinitum), there is no direct reason for a person to state the fact. Humans, though, aren’t omniscient agents with perfect memories. If some fact remains unstated for too long (because of it’s mutually-understood “obviousness,”) it can drift out of some people’s—or everyone’s—conscious consideration.

2. Signalling

No blog post would be complete without a more cynical explanation. I don’t think this one is entirely disentangled from the former—rather, this might be the mechanism by which the “humans in air” phenomenon occurs. There are couple different points here:

Coming up with indirect, non-obvious effects of some policy or idea signals intelligence or wit.

Explicitly stating obvious, first-order effects might signal social ineptitude and/or lack of wit.

The first point is pretty self-explanatory; you don’t get smart points for saying “money lets people buy things,” but you do get smart points for saying “a basic income decreases downside risk associated with entrepreneurship, so we should expect it to boost socially-productive innovation and risk taking.”

The second is more subtle, For one thing, stating the obvious might indicate that you don’t know the direct effect is “common knowledge.” Think of a math major working on homework with a friend who says out loud “since 3x=15, we can divide both sides by 3 which means that x=5.” Sounds kinda dumb, right? Math majors are *supposed* to know that the mechanics of this operation are trivial and obvious.

This itself can have two implications

A lack of social awareness about what is common knowledge (that ‘everyone knows we can divide both sides by 3’)

A lack of direct knowledge/intelligence/wit (that the operation in question is trivial to the speaker himself).

Countersignaling

My favorite part of our signaling-centric-psychology is countersignaling.

If not stating the obvious signals some amount of wit, stating the obvious might come to signal that a person is so self-assured of his social status and intelligence that he isn’t worried about coming across as dumb or inept. Further, at some point the “obvious” first order effects stop being obvious, so stating them is a sort of direct signal of independent thinking.

That’s what I’m taking advantage of with this blog post! At least consciously, I am intending to do more of the “‘obvious’ things aren’t obvious anymore” thing instead of the “I’m so secure that I can state something that is genuinely obvious to everyone” countersignal, but there might be some of that going on as well.

3. Domains of respectability

A third explanation involves the fact that some types of effects or values are considered more important/legitimate or higher status than others. The pleasure people get from heroin is regarded as lower and less valuable than the social benefits associated with reducing mass-incarceration, regardless of which is larger in an absolute utilitarian sense.

I’m not quite sure why, but it seems that simple, first-order effects are often indeed lower status than higher-order effects. Perhaps it has something to do with direct effects often affecting people at the individual level, whereas secondary effects are more likely to affect communities and societies.

Once again, I am unsure how entangled this is with the last two explanations; it doesn’t seem entirely distinct. Focusing on high status second-order concerns might be a signal that one has lofty, respectable values, but it also might just be a more directly effective argument in favor of one’s point.

Conclusion

I’ve relied heavily on the examples of drug use, exercise, and public cash assistance, but I can think of more.

D.C. statehood being considered solely in terms of its effect on electoral politics rather than in terms of whether its citizens should have political representation, a point made by countersignaling-extraordinaire Ezra Klein.

2. Universal healthcare being considered in terms of its effect on total healthcare spending, aggregate public health, or labor market fluidity instead of whether it would directly improve people’s lives (proof).

3. Neglecting the intrinsic value of hobbies/activities of any kind, as with this poster:

Is there any hope that we can elevate the salience of direct effects? I think so!

We’re already seeing some improvements in the “give people cash” discourse as I described above. As folks realize that “obvious,” “common knowledge” things are no longer so obvious, emphasizing direct effects will become more directly appealing as an argumentative device and will come to signal wit instead of ineptitude.

So, take advantage of countersignaling and make some stupidly-obvious points that aren’t getting made!

I’ve noticed a similar neglect of obvious first order effects too. Intuitively the signalling and counter-signalling explanations seem the most likely to be correct to me.

This reminds me of the following popular meme template:

In this template you have very smart people and very dumb people coming to the same conclusion by using similar simple arguments, while the moderately intelligent come up with complex, clever, but ultimately wrong arguments for why the obvious policy choice is incorrect. Here, I’ve made a version with the very dumb & very smart arguing that death is bad using the obvious argument that “it kills people”, while the moderately intelligent person argues that death is good because of various commonly argued second-order pro-death arguments.

Parenting advice is an interesting example that might shed some light on what’s going on here. It’s 100% clear that as a parent you are “supposed” to care entirely for your kid’s long-term well-being, ignoring the short term, and short term considerations are only important as a kind of practical “you can only push so hard” issue. The more you manage to successfully optimize your kid for the long term, the better a parent you are in the eyes of society, and that’s all there is to it.

Humans do tend to favor the short term in most domains, sometimes to what seems like a stupid degree. It seems to me that in general, many direct effects are short-term effects, and many second-order effects are postulated long-term effects. So maybe exhorting about second-order effects and ignoring direct effects are really an attempt to get people to pay an appropriate amount of heed* to the long term. I certainly see that in some of your examples.

* As Eliezer memorably wrote in his meta-honesty post:

I very much, personally, disagree with the parenting philosophy you’ve outlined! (I’m NOT also claiming that you share that philosophy. I hope you don’t!)

Children – and everyone is one! – only have one life! There is no ‘long-term’ – when does that start? At 30? 40? 50?

The long-term includes now! It started in the past actually. And the point really is (or should be) to ‘maximize the integral’ of ‘living a good life’, not preparing for some ‘future’ that never arrives.

As a parent myself, I want my child to live a great life, including today, tomorrow, both short-term, and long. I don’t want to reward them only because of a practical “you can only push so hard” limitation on the amount of unpleasantness they can bear.

I also want to push back on this being “100% clear … in the eyes of society”. There are others that disagree with this as I do. And I’d expect most people do too, to at least some extent. People’s ‘revealed preferences’ certainly don’t seem to match these supposed prescriptions – not generally and definitely not “100%”.

That’s fair, I might have been being a little hyperbolic, and I don’t mean to say that no other people care about kids’ short-term well-being. I was more pointing at the fact that if you look for discussions or advice about parenting decisions (e.g. what school to go to, how to interact with them, what activities they should do day-to-day) the majority of the focus will typically be on medium- and long-term effects (e.g. educational outcomes, behavioral training, physical and cognitive development) while ignoring the obvious direct effects on the kid, much like the example in the post about the benefits of tennis.

Yes, that’s a good point – and it’s probably, at least partly, a ‘selection effect’ too, i.e. parents that actively seek advice are probably those that are (overly) worried about medium and long term effects/consequences. And it’s certainly the case that some parents, or all parents some of the time, neglect important the medium and long term.

But there is parenting advice along the lines of what I endorse – and it’s great! And I think many people do support a lot of things along those lines, if only tacitly, e.g. ‘free range’ kids kinds of things.

(And of course I’m incredibly sympathetic to parents that are terrified of harming their children in any way, especially inadvertently. It really is an awesome responsibility!)

Have you considered the possibility that people do not list first-order effects to individuals because huge swaths of the political establishment do not actually care about people they don’t know?

The water they swim, the air they breathe: Bringing up how something affects the outgroup’s feefees is not “obvious” or “direct”, it’s bringing up Nth-order civil breakdown effects in the most vague and indirect way possible, with figuring out all the critical details left as an exercise for the listener.

We live in a society; aka we have a tenuous contract to be copacetic and trade resources with others. They give the smallest amount of fucks about the outgroup’s happiness because an unhappy outgroup may have second-order effects in breaking down civil society with associated third-order effects on them and theirs.

I think this fails to explain why even when the people talking are directly affected (such as with the UBI example, which would affect everyone) we don’t see as much focus on the direct effects of the policy.

This leads me to believe it could somewhat be the opposite of what you suggested. If I say that UBI would give people money, and so it’s good, people may suspect me of only advocating for a UBI because I selfishly wanted money, rather than for more pro-social reasons. However if I say UBI is good because it allows for young couples to start families, increasing the birth rate & population, then because I am not in a young couple there is no chance I could be arguing for such a policy for purely selfish reasons, so must be arguing for it because I genuinely believe it will help others.

So people may argue using nth order effects because those effects will explicitly disclude the affects of the policy on the arguer.

This is a good point. Could also be that discussing only points that might impact oneself seems more credible and less dependent on empathy, even if one really does care about others directly.

In my experience, in most crowds there are certain aspects of issues that are considered acceptable topics of conversations, and others that aren’t. Stoners are fine talking about the details of how to have fun with drugs, bad trips, the price of weed, etc. But try to discuss the research on the possible psychiatric issues of chronic marijuana use and it’s a faux pas. At the dinner tables of middle class healthcare professionals, it’s often the other way around.

This is maybe connected to the discussion around filtered evidence. The Blues only want to talk about personal experience with drugs, while the Greens only talk about it from a “public health perspective.” And yeah, when we chop up reality like this, it becomes very difficult to find the truth.

There are some pragmatic considerations to this, e.g. ‘harshing their high’. I wouldn’t think people that drink alcohol are unaware of the health risks (and other complications), so bringing it up would pretty reasonably be interpreted as criticism, or your trying to convince or persuade them to give up something they enjoy and choose to do despite the risks.

But I’ve had interesting discussions with stoners about the possible psychiatric issues of marijuana, and drinkers about their health issues due to drinking, so I’m not sure that it’s ‘unacceptable’ – at all anyways. I can certainly appreciate why anyone wouldn’t want to be ‘badgered’ about the risks of something they still choose to do! (I find it annoying when people do it to me.)

I also wouldn’t think it unreasonable that, ex. parents watching their children play American football wouldn’t also want to, at that time, talk about the attendant risks of head injuries. At least in that case, I’d presume they were already aware of the claims about those risks and had made a decision to let their kid(s) play anyways.

uuhhhh most of the middle class health care professionals I know are stoners

The image of this tweet isn’t present here, only on Substack.

Thanks very much. Just fixed that.

That assumes that decriminalization increases drug usage but it’s questionable that this is what happened. In Glenn Greenwalds Cato report which is a base for a lot of the this discussion he says: “Although postdecriminalization usage rates have remained roughly the same or even decreased slightly when compared with other EU states, drug‐related pathologies — such as sexually transmitted diseases and deaths due to drug usage — have decreased dramatically. ”

Changes in drug use is not a a direct effect of police action on drug users. The direct effect of police action on drug users is them spending time in prison.

Yes, you’re correct. As others have correctly noted, there is no unambiguous way of determining which effects are “direct” and which are not. However, suppose decriminalization does decrease drug use. My argument emphasizes that we would need to consider the reduction in time spent enjoying drugs as a downside to decriminalization (though I doubt this would outweigh the benefits associated with lower incarceration rates). It seems to me that this point would frequently be neglected.

I’ve been thinking about this – thanks!

One problem is that ‘direct’ or ‘first-order’ is ultimately nebulous. There is no unique direct effect or first-order consequence to anything, i.e. it depends crucially on context, scale, scope, etc..

Consider the direct effects or first-order consequences of a heroin overdose. Restricting ourselves to the macroscopic, i.e. human-scale, I’d imagine that a heroin overdose is initially very positive! It does seem a little … insensitive? besides the point? to emphasize “Heroin overdoses are really great until you start to die shortly thereafter!”.

A part of not emphasizing the direct effects or first-order consequences is an implicit claim that, whatever they are, they are swamped (or maybe simply just outweighed) by subsequent effects or consequences.

Hence the long-term focus of a lot of your examples, e.g. unemployment insurance, basic income.

Similarly, consider rent control – it really is awesome and amazing! At least it is for the people that ‘win the lottery’ and get to live in a rent controlled unit. And yet, overall, it’s a terrible deal for everyone.

But I’m not against including all of the effects and consequences, including the ‘direct’ or ‘first-order’ ones – we should shut up and multiply (or add, or whatever).

Indeed, and I think this is worth emphasizing.

One effect of drugs is making people feel good, but a more immediate effect is, say, molecules of THC diffusing into the bloodstream or whatever.

We could say that we don’t care about that in context but we do care about people feeling good, but… in some contexts “it makes people feel good” probably should be considered below the threshold of what we care about? At any rate it’s not obvious to me that it should never be.

Similarly, “money makes people better off” isn’t a direct effect of giving them money—it’s mediated by the fact that people can use that money to buy things. And another effect of giving someone money is (usually) that some other account somewhere now has less money, that seems equally as direct as the person in question having more money.

I do think this post is getting at something important. Like, I agree that “people too often ignore that drugs make people feel good” is likely true, and it seems plausibly relevant that it’s a now immediate effect than some others. But I also worry that “this is the immediate effect” is trying to justify them on grounds that don’t work?

And even that’s not quite completely true. I’m pretty sure people are generally happier immediately after you give them money, even before they spend it! (They correctly anticipate being able to use that money as you describe, i.e. buying or paying for things.)

Yes, that’s my ‘concern’ as well. Even when ‘direct’ effects aren’t explicitly stated, it doesn’t seem like that’s always, or even mostly, because those effects are being ignored as much as that (implicitly) they shouldn’t be the dominant consideration. That’s a harder thing to disentangle generally.

Saw an example of this in Hacker News today. California and Cambridge, MA removed algebra from their middle school math curriculum for a stated reason of equity. Here’s the Boston Globe challenging the equity argument with another equity argument:

In contrast the blogger Noahpinion points out the direct effect, but then also ties it to equity. Later he (unfairly) accuses the proponents of removing math of hereditarian, un-progressive views on education.

Why does Noahpinion mention equity even after bringing up the direct effect? I think it’s because equity is a frame that everyone (in the debate among progressives) cares about, so your argument is guaranteed to at least land. Some people care more about equity than the direct effect of teaching advanced students more math. This is basically explanation 3 (domains of respectability), but it’s less about status and more about being universally important vs maybe not important to the opponents of your argument.

I agree with the main idea. You could even argue that it’s a diseased way of thinking, in the same sense as materialism. People focus on the “objective” pros and cons, the subjective is entirely neglected.

But the person who makes music because he loves music is much more healthy than the person who makes music because he wants to sell it for money.

Your examples are mainly cases in which the direct effects are subjective and/or psychological. My creative thinking is stunted right now, but with more examples we’d be able to tell if this effect is a fallacy caused by neglecting the obvious, or if it’s a result of utilitarian thinking which neglects psychological values.

I also want to nitpick a bit: Drugs aren’t a good long-term strategy to happiness.

Edit: I was under the wrong impression that this was a new post. Oh well, surely this kind of engagement is more healthy.

Four arguments you start with also have “heres what I think other people should do” in common. If someone is deciding on whether or not use drugs or whether or not to exercise they will not miss the “fun” and “sucks” parts you point out below. When you Hanson out the “real” goal of saying something like that it’s not strange at all, altho it might be explaining away too much, I’m not sure.

Good post. I think when you look at the likely neural wiring underlying concerns like the ones you’re bringing up, it’s simply the case that unless you’ve developed the type of logic loops which actively consider these types of issues, they just don’t occur to most people at a conscious level. This is an argument for the “Fish in the water” possibility.

For instance, the first ‘caveperson’ who discovered that eating rotten food would likely make you sick might have gone around telling everyone that “eating rotten food might make you sick” as he or she had probably eaten rotten food, gotten sick but didn’t die.

This meant their brains created a new circuit which equated the experience of eating rotten food, getting sick, and then not being sick after they recovered, and ‘making the connection’ between these experiences, neurally speaking. The risk of death involved would likely recruit a large amount of neural wiring to cement the importance of this event into their very being.

Additionally, they could report back to people why they got sick becausethey had lived to talk about it, and could now formulate a plan to avoid getting sick and possibly dying from the same thing in the future.

So this news might have started the rounds in the tribe, and all of a sudden there was legislation passed to look for rotten food and discard it, and everyone’s neural circuitry was modified to include this new idea that rotten food was unsafe and might be the cause for many of the mysterious deaths in the tribe. Because they only had one media outlet they all paid attention to, which had really good investigation and reporting and didn’t serve up opinion as fact or twist the facts in horrible and destructive ways, this new idea of Food Safety was communicated and absorbed efficiently by all members of the tribe with a few exceptions.

Some people, liked to eat rotten food, maybe they fermented grapes or hops or something which turned into alcohol, so they argued that it wasn’t all rotten food that would kill you, as the neural wiring they had, included this enjoyment of fermented foods.

All of these ideas though, the arguments and counter-arguments, were ‘at the forefront’ of the tribes thinking as the top level thinking they were doing included these concepts and the neural wiring which encoded these ideas in their brains was at the top levels of consideration in these thought loops., both at the individual level and at the tribal level, as the neural loops in the individuals brains resembled the logic loops formed in the tribe as certain members discussed certain things with some people, but discussed other things with other people, and might totally avoid even crossing paths with yet others so that no discussion took place.

As time progressed though, this wiring became lower level consideration as it was consolidated into larger thoughts and ideas, as additional experiences caused that wiring to become tertiary or below higher order thinking. The people who made alcohol might have created businesses so that their major concerns regarding these concepts were economically based, and since the tribe was dealing with this issue of rotten food, instead of just at an individual level of concern, fewer people were getting sick and dying.

Much later though, people just began to assume the food they ate was safe because other people were supposed to be concerned with these issues. Food safety legislation created a group of people who kept ideas about rotten food at the forefront of their minds all the time, so that other people didn’t have to waste mental and physical effort to do so. This tribe delegated the work of maintaining Food Safety to Food Inspectors, who were ‘experts’ in the field.

So the amount of neural wiring and circuitry dealing with these ideas in the broader tribe became less and less as they relied on the experts to maintain food safety more and more. So the obviousness of safety issues of Food was pruned from the neural circuitry of the majority of the tribe, so that they could grow new neurons and make connections between other concepts and help the tribe progress in other ways.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Much later on though, we have the Internet, which allows everyone to be an expert on everything! There are few real experts left because of the democratization of knowledge and expertise, and the growing field of AI and ML means eventually humans won’t need to devote any neural wiring to anything but the cultivation of pleasure!

We will off load all this horrible ‘thinking about uncomfortable things’ and ‘critically thinking about our culture’ to computers so we won’t have to worry anymore! Instead we will focus on ‘lolz’ and creating new memes and doing drugs and reproducing in the correct proportions, even though computers will still come up with funnier/more ironic lolz and deeper and more meaningful memes, and will create better drugs and allow us to experience the best sex humans have ever had!

The matrix seems scary until you realize there won’t be any Morpheus’s to wake us from our dreams, so we’ll never know it when all of our neural wiring has been repurposed for reasons we’ll never know about! We will finally become real fish, without the ability to even contemplate the water around us! At that point, even talking about the obvious implications of flawed application of technological effort will seem so lower class everyone will just ignore it and laugh while they get high off rotten food and have orgasms which last for days at a time!

The Left seems to think all social issues boil down to education, not taking into account some people are just stupid. The Right tends to think that all social issues have roots in lack of motivation/taking personal responsibility, without taking into account that there are many in circumstances that just cannot exercise those without hurting others.

Mod note: We generally try to keep generalizations about political parties, and general central culture-war stuff out of most of the site discussion. I think this comment is fine, but I would prefer the comments on this post not become a “the left thinks or the right thinks” type of discussion, which I think is rarely fruitful.

Just wanna say I think this is good moderation policy, and thank you for upholding it.

I’m not sure what you mean by “this is comment is fine”. I don’t think it’s a good comment, but I don’t have strong feelings about it, e.g. being deleted.

Yeah, I meant it as “I think this comment is OK and shouldn’t be deleted or cause the author to get a warning, but it seemed like the kind of thing that could lead to followup comments that would be quite bad”

Thanks for the clarification! I think your “mod note” comment serves as an effective and eminently sensible ‘warning’ anyways.