A Conservative Vision For AI Alignment

Current plans for AI alignment (examples) come from a narrow, implicitly filtered, and often (intellectually, politically, and socially) liberal standpoint. This makes sense, as the vast majority of the community, and hence alignment researchers, have those views. We, the authors of this post, belong to the minority of AI Alignment researchers who have more conservative beliefs and lifestyles, and believe that there is something important to our views that may contribute to the project of figuring out how to make future AGI be a net benefit to humanity. In this post, and hopefully series of posts, we want to lay out an argument we haven’t seen for what a conservative view of AI alignment would look like.

We re-examine the AI Alignment problem through a different, and more politically conservative lens, and we argue that the insights we arrive at could be crucial. We will argue that as usually presented, alignment by default leads to recursive preference engines that eliminate disagreement and conflict, creating modular, adaptable cultures where personal compromise is unnecessary. We worry that this comes at the cost of reducing status to cosmetics and eroding personal growth and human values. Therefore, we argue that it’s good that values inherently conflict, and these tensions give life meaning; AGI should support enduring human institutions by helping communities navigate disputes and maintain norms, channeling conflict rather than erasing it. This ideal, if embraced, means that AI Alignment is essentially a conservative movement.

To get to that argument, the overarching question isn’t just the technical question of “how do we control AI?” It’s “what kind of world are we trying to create?” Eliezer’s fun theory tried to address this, as did Bostrom’s new “Deep Utopia.” But both of these are profoundly liberal viewpoints, and see the future as belonging to “future humans,” which often envisions a time when uploaded minds and superintelligence exist, and humanity as it traditionally existed will no longer be the primary mover of history. We want to outline an alternative which we think is more compatible with humanity as it exists today, and not incidentally, one that is less liable to failure.

This won’t be a treatise of political philosophy, but it’s important as background, so that is where we will start. We’ll start by explaining our lens on parts of the conservative-liberal conceptual conflict, and how this relates to the parent-child relationship, and then translate this to why we worry about the transhuman vision of the future.

In the next post, we want to outline what we see as a more workable version of humanity’s relationship with AGI moving forward. And we will note that we are not against the creation of AGI, but want to point towards the creation of systems that aren’t liable to destroy what humanity values.

Conservatives and liberals

“What exactly are conservatives conserving?” – An oft-repeated liberal jab

The labels “conservative” and “liberal” don’t specify what the contested issues are. Are we talking about immigration, abortion rights or global warming? Apparently it doesn’t matter—especially in modern political discourse, there are two sides, and this conflict has persisted. But taking a fresh look, it might be somewhat surprising that there are even such terms as “conservatives” and “liberals” given how disconnected the views are from particular issues.

We propose a new definition of “conservative” and “liberal” which explains much of how we see the split. Conservatives generally want to keep social rules as they are, while liberals want to change them to something new. Similarly, we see a liberal approach as aspiring to remove social barriers, unless (perhaps) a strong-enough case can be made for why a certain barrier should exist. The point isn’t the specific rule or norm. A conservative approach usually celebrates barriers, and rules that create them, and ascribes moral value to keeping as many barriers as possible. For instance, the prohibition on certain dress codes in formal settings seems pointless from a liberal view—but to a conservative, it preserves a shared symbolic structure.

It’s as if the people who currently say “No, let’s not allow more people into our country” and the people who say “No, let’s not allow schools to teach our children sex education” just naturally tend to be good friends. They clump together under the banner “keep things as they are”, building a world made of Chesterton’s fences, while the people who say “let’s change things” clump in another, different world, regardless of what those things are. Liberals, however, seem to see many rules, norms, or institutions as suspect until justified, and will feel free to bend or break them; conservatives tend to see these as legitimate and worth respecting until proven harmful. That instinct gap shapes not just what people want AI to do—but how they believe human societies work in the first place.

Disagreement as a Virtue

It’s possible that the school of thought of agonistic democracy (AD) could shed some light on the above. AD researchers draw the distinction between two kinds of decision-making:

Deliberative decision-making, in which the multiple parties have a rational discussion about the pros and cons of the various options; and

Agonistic decision-making, in which the power dynamics and adversity between the multiple parties determine the final decision.

AD researchers claim that while agonistic decision-making may seem like an undesirable side-effect, it is a profoundly important ingredient in a well-functioning democracy. Applying this logic to the conservative-liberal conflict, we claim that much of the conflict between a person who says “Yes!” and a person who says “No!” is more important for discussing the views than what the question even was. Similarly, one side aims for convergence of opinions , the other aims for stability and preserving differences.

Bringing this back to alignment, it seems that many or most proposals to date are aiming for a radical reshaping of the world. They are pushing for transformative change, often in their preferred direction. Their response to disagreement is to try to find win-win solutions, such as the push towards paretotopian ideals where disagreements are pushed aside in the pursuit of radically better worlds. And this is assuming that increasingly radical transformation will grow the pie and provide enough benefits to override the disagreement—because this view assumes the disagreement was never itself valuable.

Along different but complementary lines, the philosopher Carl Schmitt argued that politics begins not with agreement, or deliberation, but with the friend–enemy distinction. Agonistic democracy builds on a similar view: real social life isn’t just cooperation, it’s structured disagreement. Not everyone wants the same thing, and they shouldn’t have to. While Schmitt takes the primacy of ineliminable conflict ever farther, Mouffe and others suggest that the role of institutions is not to erase conflict, but to contain it. They agree, however, that conflict is central to the way society works, not something to overcome.

Parents and children

We can compare the conflict between conservatives and liberals to the relationship between parents and children[1]. In a parent-child relationship, children ask their parents for many things. They then often work to find the boundaries of what their parents will allow, and lead long-term campaigns to inch these boundaries forward.

Can I have an ice cream? Can I stay another 5 minutes before going to bed? Can I get my own phone when I’m 9? When could I get a tattoo? Try one argument, and if it fails, try another until you succeed. If mom says no, ask dad. You can get a hundred nos, but if you get one yes, you have now won the debate permanently, or at least set a precedent that will make it easier to get a yes next time. If you have an older sibling, they may have done much of the work for you. There is already a mass of “case law” that you can lean on. Parents may overturn precedents, but that requires them to spend what little energy they have left after their workday to get angry enough for the child to accept the overturn.

One extreme view of this, which is at least prevalent in the effective altruist / rationalist communities, is that children should be free to set the course of their own lives. I know of one parent that puts three dollars aside each time they violate the bodily sovereignty of their infant—taking something out of their mouth, or restricting where they can go. Eliezer similarly said that the dath-ilani version is that “any time you engage in an interaction that seems net negative from the kid’s local perspective you’re supposed to make a payment that reflects your guarantee to align the nonlocal perspective.” This view is that all rules are “a cost and an [unjustified, by default,] imposition.” Done wisely and carefully, this might be fine—but it is setting the default against having rules.

And if a parent is discouraged from making rules, the dynamic ends up being similar to a ratchet; it can mostly only turn one way. Being on the conservative side of this war is terrifying. You can really only play defense. Any outpost you lose, you have lost permanently. Once smartphones became normal at age 10, no future parent can ‘undo’ that norm without being perceived as abusive or weird. As you gaze across the various ideals that you have for what you want your family life to look like, you’re forced to conclude that for most of these, it’s a question of when you’ll lose them rather than if.

AGI as humanity’s children

We would like to expand the previous analogy, and compare the relationship between humanity and AGI to the relationship between parents and their children. We are not the first to make this comparison; however, we argue that this comparison deserves to be treated as more than just a witty, informal metaphor.

We argue that the AI alignment problem, desperately complicated as it is, is a beefed-up version of a problem that’s barely tractable in its own right: The child alignment problem. Parents want their children to follow their values: moral, religious, national, interpersonal, and even culinary and sports preferences, or team allegiances. However, children don’t always conform to their parents’ plans for them. Of course, as we get to the later categories, this is less worrisome—but there are real problems with failures.

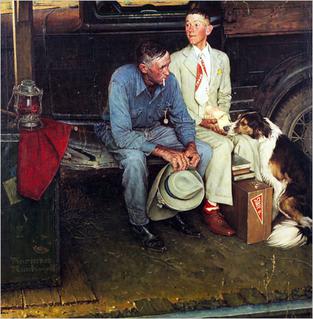

The child alignment problem had tormented human parents throughout known history, and thus became an evergreen motif in art, from King Lear to Breaking Home Ties to The Godfather to Pixar’s Up. Children’s divergence is not just an inconvenience; it’s an integral, profound component of the human condition. This statement might even be too human-centric, as animal parents reprimand their offspring, repeatedly, with the same kind of visible frustration and fatigue that we observe in human parents. Self-replication is an essential property of life; thus the desire to mold another being in one’s image, and in turn to resist being molded by another, are not merely challenges, but likely contenders for an answer to the question, “what is the meaning of life?”

Let’s descend from the height of the previous paragraph, and ask ourselves these questions: “How does this connect with AI alignment? And what useful lessons can we take from this comparison?”

The answer to the first question is straightforward: The AI alignment problem is a supercharged version of the child alignment; it has all of the complexities of the latter, compounded with our uncertainty of the capabilities and stability of this new technology. We struggle to mold AGI in our image, not knowing how insistent or resourceful it will be in resisting our molding.

We offer the following answer to the second question: The child alignment problem is decidedly not an optimization problem. One does not win parenthood by producing a perfect clone of oneself, but rather by judiciously allowing the gradual transformation of one’s own ideals from subject to object. A cynical way to put the above in plain words is “you can’t always get what you want”; more profoundly, that judicious transformation process becomes the subject. The journey becomes the destination.

People ask what an AI-controlled autonomous vehicle will do when faced with a trolley problem-like situation; stay on course and kill multiple people, or veer and kill one person. We care so much about that, but we’re complacent with humans killing thousands of other humans on the road every day. We care intensely about what choice the AI will make, though we’ll get angry at it regardless of which choice it’ll make. There isn’t really a right choice, but we have an intense desire to pass our pain forward to the AI. We want to know that the AI hurts by making that choice.

In this framing, we aren’t just interested in the safety of AI systems. We want to know that it values things we care about. Maybe we hope that seeing bad outcomes will “hurt” even when we’re not there to give it a negative reward signal. Perhaps we want the AI to have an internal conflict that mirrors the pain that it causes in the world. Per agonistic democracy, we don’t want the AI to merely list the pros and cons of each possible choice; we want the conflict to really matter, and failure to tear its insides to shreds, in the same way it tears ours. Only then will we consider AI to have graduated from our course in humanity.

Holism and reductionism

Another related distinction is between holism (“the whole is greater than the sum of its parts”) and reductionism (“the whole is the sum of its parts”) . When children argue for activities to be allowed, they take a reductionist approach, while parents tend to take a holistic approach. Children want to talk about this specific thing, as separate from any other things. Why can’t I stay up late? Because you have school tomorrow. Okay, but why can’t I stay up late on the weekend? Because… It’s just too similar to staying up late on a weekday, and it belongs to a vague collection of things that children shouldn’t do. If you argue for each of these items separately, they will eventually get sniped one-by-one, until the collection dissolves to nothing. The only way they can stay safe is by clumping together. That is a holistic approach.

In the struggle between a conservative and a liberal, the conservative finds that many of the items they’re defending are defined by pain. If we align an AI along what we call the liberal vision, to avoid or eliminate pain, in the extreme we have an AI that avoids moral discomfort, and will avoid telling hard truths—just like a parent who only ever says yes produces spoiled kids. And in a world of AI aligned based on avoiding anything bad, where it optimizes for that goal, a teenager might be offered tailored VR challenges that feel deeply meaningful without ever being told they can’t do anything.

This means that the conservative involuntarily becomes the spokesperson for pain, and in the liberal view, their face becomes the face of a person who inflicts pain on others. This point connects to the previously-mentioned agonistic democracy, as “agonistic” derives from the latin “agōn”, which also evolved into “agony”. And if we add the utilitarian frame where pleasure is the goal, this pain is almost definitionally bad—but it’s also what preserves value in the face of optimization of (inevitably) incompletely specified human values.

Optimizers destroy value, conservation preserves pain

Optimizers find something simple enough to maximize, and do that thing. This is fundamentally opposed to any previously existing values, and it’s most concerning when we have a strong optimizer with weak values. But combining the idea of alignment as removing pain, and optimizing for this goal means that “avoidance of pain” will erase even necessary friction—because many valuable experiences (discipline, growth, loyalty) involve discomfort. And in this view, the pain discussed above has a purpose.

Not suffering for its own sake, or trauma, but the kind of tension that arises from limits, from saying no, from sustaining hard-won compromises. In a reductionist frame, every source of pain looks like a bug to fix, any imposed limit is oppression, and any disappointment is something to try to avoid. But from a holistic view, pain often marks the edge of a meaningful boundary. The child who’s told they can’t stay out late may feel hurt. But the boundary says: someone cares enough to enforce limits. Someone thinks you are part of a system worth preserving. To be unfairly simplistic, values can’t be preserved without allowing this pain, because limits are painful.

And at this point, we are pointing to a failure that we think is uncontroversial. If you build AI to remove all the pain, it starts by removing imposed pain—surely a laudable goal. But as with all unconstrained optimizers, this will eventually run into problems, in this case, the pain imposed by limitations[2] - and one obvious way to fix this is by removing boundaries that restrict, and then removing any painful consequences that would result. That’s not what we think alignment should be. That’s cultural anesthesia.

But we think this goes further than asking not to make a machine that agrees with everyone. We need a machine that disagrees in human ways—through argument, ritual, deference, even symbolic conflict. But what we’re building is very much not that—it’s sycophantic by design. But the problems AI developers admitted in recent sycophantic models wasn’t that they realized they were mistaken about the underlying goal, it was that they were doing it ham-handedly.

Again, most AI alignment proposals want to reduce or avoid conflict, and the default way for this to happen is finding what to maximize—which is inevitable in systems with specific goals—and optimize for making people happy. The vision of “humanity’s children” unencumbered by the past is almost definitionally a utopian view. But that means any vision of a transhuman future built along these lines is definitionally arguing for the children’s liberalism instead of the parent’s conservatism. If you build AI to help us transcend all our messy human baggage, it’s unclear what is left of human values and goals.

Concretely, proposals’ like Eliezer’s Coherent Extrapolated Volition, or Bostrom’s ideas about Deep Utopia assume or require value convergence, and see idealization as desirable and tractable. Deep Utopia proposes a world where we’ve “solved” politics, suffering, and scarcity—effectively maximizing each person’s ability to flourish according to their own ideals. Eliezer’s Fun Theory similarly imagines a future where everyone is free to pursue deep, personal novelty and challenge. Disagreement and coordination problems are abstracted away via recursive preference alignment engines and “a form of one-size-fits-all ‘alignment’”. No one tells you no. But this is a world of perfect accommodation and fluid boundaries. You never need to compromise because everything adapts to you. Culture becomes modular and optional. Reductionism succeeds. Status becomes cosmetic. Conflict is something that was eliminated, not experienced nor resolved. And personal growth from perseverance, and the preservation of now-vestigial human values are effectively eliminated.

In contrast, a meta-conservative perspective might say: values don’t converge—they conflict, and the conflicts themselves structure meaning. Instead of personalized utopias, AGI helps steward enduring human institutions. AI systems help communities maintain norms, resolve disputes, and manage internal tensions, but without flattening them. This isn’t about eliminating conflict. Instead, it supposes that the wiser course is to channel it. This isn’t about pessimism. It’s about humility and the recognition that the very roughness we want to smooth over might be essential to the things holding everything together[3].

And the critical question isn’t which of these is preferable—it’s which is achievable without destroying what humans value. It seems at least plausible, especially in light of the stagnation of any real robust version of AI alignment, that the liberal version of alignment has set itself unachievable goals. If so, the question we should be asking now is where the other view leads, and how it could be achieved.

That is going to include working towards understanding what it means to align AI after embracing this conservative view, and seeing status and power as a feature, not a bug. But we don’t claim to have “the” answer to the question, just thoughts in that direction—so we’d very much appreciate contributions, criticisms, and suggestions on what we should be thinking about, or what you think we are getting wrong.

Thanks to Joel Leibo, Seb Krier, Cecilia Elena Tilli, and Cam Allen for thoughts and feedback on a draft version of this post

- ^

In an ideal world, this conflict isn’t acrimonious or destructive, but the world isn’t always ideal—as should be obvious from examples on both sides of the analogy.

- ^

Eliezer’s fun theory—and the name is telling—admits that values are complex, but then tries to find what should be optimized for, rather than what constraints to put in place.

- ^

Bostrom argues (In Deep Utopia, Monday—Disequilibria) that global externalities require a single global solution. This seems to go much too far, and depends on, in his words, postulating utopia.

This is a strange post to me.

On the one hand, it employs oversimplified and incorrect models of political discourse to present an inaccurate picture of what liberalism and conservatism stand for. It also strongly focuses on an analogy for AGI as humanity’s children, an analogy that I think is inappropriate and obscures far more than it reveals.

On the other hand, it gets a lot of critical details exactly right, such as when it mentions how “proposals like Eliezer’s Coherent Extrapolated Volition, or Bostrom’s ideas about Deep Utopia assume or require value convergence, and see idealization as desirable and tractable.”

But beyond these (in a relative sense) minute matters… to put it in Zvi’s words, the “conservative”[1] view of “keep[ing] social rules as they are” simply doesn’t Feel the ASI.[2] There is no point in this post where the authors present a sliver of evidence for why it’s possible to maintain the “barriers” and norms that exist in current societies, when the fundamental phase change of the Singularity happens.

The default result of the Singularity is that existing norms and rules are thrown out the window. Not because people suddenly stop wanting to employ them[3], not because those communities rebel against the rules[4], but simply because those who do not adapt get economically outcompeted and lose resources to those who do. You adapt, or you die. It’s the Laws of Economics, not the Laws of Man, that lead to this outcome.[5] Focusing exclusively on the latter, as the post does, on how we ought to relate to each other and what moral norms we should employ, blah blah blah, is missing the forest for a (single) tree. It’s a distraction.

There are ways one can believe this outcome can be avoided, of course. If strong AGI never appears anytime soon, for example. If takeoff is very slow and carefully regulated to ensure society always reaches an equilibrium first before any new qualitative improvement in AI capabilities happens. If a singleton takes absolute control of the entire world and dictates by fiat that conservatism shall be allowed to flourish wherever people want it to, forcefully preventing anyone else from breaking barriers and obtaining ever-increasing resources by doing so.

I doubt the authors believe in the former two possibilities.[6] If they do, they should say so. And if they believe in the latter, well… building an eternally unbeatable norm-enforcing God on earth is probably not what “conservatives” have in mind when they say barriers should be maintained and Schelling fences should be maintained and genuine disagreement should be allowed to exist.

Again, this isn’t what conservatism stands for. But I’ll try to restrain myself from digressing into straight-up politics too much

I’d even go a lot further and say it doesn’t feel… regular AI progress? Or even just regular economic progress in general. The arguments I give below apply, with lesser force of course, even if we have “business as usual” in the world. Because “business as usual,” throughout all of human history and especially at an ever-increasing pace in the past 250 years, means fundamental changes in norms and barriers and human relations despite conservatives standing athwart history, yelling stop

Except this does happen, because the promise of prosperity and novelty is a siren’s call too alluring to resist en masse

Except this also happens, if only because of AIs fundamentally altering human cognition, as is already starting to happen and will by default be taken up to eleven sometime soon

See The benevolence of the butcher for further discussion.

Which doesn’t mean these possibilities are wrong, mind you.

I won’t try to speak for my co-author, but yes, we agree that this doesn’t try to capture the variety of views that exist, much less what your view of political discourse should mean by conservatism—this is a conservative vision, not the conservative vision. And given that, we find the analogy to be useful in motivating our thinking and illustrating an important point, despite that fact that all analogies are inexact.

That said, yes, I don’t “feel the AGI” in the sense that if you presume that the singularity will happen in the typically imagined way, humanity as we know it doesn’t make it. And with it goes any ability to preserve our current values. I certainly do “feel the AGI” in thinking that the default trajectory is pointed in that direction, and accelerating, and it’s not happening in any sense in a fashion that preserves any values whatsoever, conservative or otherwise.

But that’s exactly the point—we don’t think that the AGI which is being aimed for is a good thing, and we do think that the conversation about the possible futures humanity could be aiming for is (weirdly) narrowly constrained to be either a pretty bland techno-utopianism, or human extinction. We certainly don’t think that it’s necessary for there to be no AGI, and we don’t think that eternal stasis is a viable conservative vision either, contrary to what you assume we meant. But as we said, this is the first post in a series about our thinking on the topic, not a specific plan, much less final word on how things should happen.

That’s all fine and good if you plan on addressing these kinds of problems in future posts of your series/sequence and explain how you think it’s at all plausible for your vision to take hold. I look forward to seeing them.

I have a meta comment about this general pattern, however. It’s something that’s unfortunately quite recurrent on this site. Namely that an author posts on a topic, a commenter makes the most basic objection that jumps to mind first, and the author replies that the post isn’t meant to be the definitive word on the topic and the commenter’s objection will be addressed in future posts.[1]

I think this pattern is bad and undesirable.[2] Despite my many disagreements with him and his writing, Eliezer did something very, very valuable in the Sequences and then in Highly Advanced Epistemology. He started out with all the logical dependencies, hammering down the basics first, and then built everything else on top, one inferential step at a time.[3] As a result of this, users could verify the local validity of what he was saying, and when they disagreed with him, they knew the precise point where they jumped off the boat of his ideology.[4] Instead of Eliezer giving his conclusions without further commentary, he gave the commentary, bit by bit, then the conclusions.

In practice, it generally just isn’t. Or a far weaker or modified version of it is.

Which doesn’t mean there’s a plausible alternative out there in practice. Perhaps trying to remove this pattern imposes too much of a constraint on authors and instead of them writing things better (from my pov), they instead don’t write anything at all. Which is a strictly worse outcome than the original.

That’s not because his mind had everything cleanly organized in terms of axioms and deductions. It’s because he put in a lot of effort to translate what was in his head to what would be informative for and convincing to an audience.

Which allows for productive back-and-forths because you don’t need to thread through thousands of words to figure out where people’s intuitions differ and how much they disagree with, etc.

I often have the opposite complaint, which is that when reading a sequence, I wish I knew what the authors’ bottom line is, so I can better understand how their arguments relate and which ones are actually important and worth paying attention to. If I find a flaw, does it actually affect their conclusions or is it just a nit? In this case, I wish I knew what the authors’ actual ideas are for aligning AI “conservatively”.

One way to solve both of our complaints is if the authors posted the entire sequence at once, but I can think of some downsides to doing that (reducing reader motivation, lack of focus in discussion), so maybe still post to LW one at a time, but make the entire sequence available somewhere else for people to read ahead or reference if they want to?

We’re very interested in seeing where people see flaws, and there’s a real chance that they could change our views. This is a forum post, not a book, and the format and our intent sharing it differs. That is, if we had completed the entire sequence before starting to get public feedback, the idea of sharing the full seuquence at the start would work—but we have not. We have ideas, partial drafts, and some thoughts on directions to pursue, but it’s not obvious that the problems we’re addressing are solvable, so we certainly don’t have final conclusions, nor do I think we will get there when we conclude the sequence.

Also the fact that you don’t get to use real-time feedback from readers on what their disagreements/confusions are, allowing you to change what’s in the sequence itself or to address these problems in future posts.

Anyway, I don’t have a problem with authors making clear what their bottom line is.[1] I have a problem with them arguing for their bottom line out of order, in ways that unintentionally but pathologically result in lingering confusions and disagreements and poor communication.

If nothing else, reading that tells you as a reader whether it’s something you’re interested in hearing about or not, allowing you to not waste time needlessly if it’s the latter

I’m confused by this criticism. You jumped on the most the most basic objection that jumps to mind first based on what you thought we were saying—but you were wrong. We said, explicitly, that this is “our lens on parts of the conservative-liberal conceptual conflict” and then said “In the next post, we want to outline what we see as a more workable version of humanity’s relationship with AGI moving forward.”

My reply wasn’t backing out of a claim, it was clarifying the scope by restating and elaborating slightly something we already said in the very first section of the post!

The objection isn’t the liberal/conservative lens. That’s relatively minor, as I said. The objection is the viability of this approach, which I explained afterwards (in the final 4 paragraphs of my comment) and remains unaddressed.

The viability of what approach, exactly? You again seem to be reading something different than what was written.

You said “There is no point in this post where the authors present a sliver of evidence for why it’s possible to maintain the ‘barriers’ and norms that exist in current societies, when the fundamental phase change of the Singularity happens.”

Did we make an argument that it was possible, somewhere, which I didn’t notice writing? Or can I present a conclusion to the piece that might be useful:

”...the question we should be asking now is where [this] view leads, and how it could be achieved.

That is going to include working towards understanding what it means to align AI after embracing this conservative view, and seeing status and power as a feature, not a bug. But we don’t claim to have ‘the’ answer to the question, just thoughts in that direction—so we’d very much appreciate contributions, criticisms, and suggestions on what we should be thinking about, or what you think we are getting wrong.”

I strong upvoted this because I thought the discussion was an interesting direction and it had already fallen off the frontpage. I don’t know that I particularly agree with the reasoning. (I am generally liberal, though have updated a bit towards being more conservative-as-described-here on the margin in recent years. I found the general framing of liberal vs conservative as described here an interesting as a lens to look through)

I do feel like this somewhat overstates the values-difference with Fun Theory, and feels like it’s missing the point of Coherent Extrapolated Volition.

I don’t think CEV at it’s core assumes this. I think that, while writing CEV makes a prediction that, if people knew more, thought longer, and grew up together more, a lot of disagreements would melt away and there would turn out to be a lot that humanity wants in common. But, CEV is designed to do pretty well even in worlds where that is false (if it’s maximally false, the CEV just throws an error. But in worlds where things only partially cohere, well, the AI helps out with those parts as best it can in a way that everyone agrees is good.

There also nothing intrinsically anti-conservative about what it’ll end up with, unless you think people would be less conservative after thinking longer and learning more and talking with each other more. (do you think that?). Yeah, lots of LWers probably lean towards expecting it’ll be more liberal, but, that’s just a prediction, not a normative claim CEV is making.

Somewhat relatedly, in Free to Optimize (which is about humans being able to go about steering their lives, not about an AI or anyone “hardcore optimizing”) Eliezer says:

This feels more like a vision of “what constraints to put in place” than “what to optimize for.”

(I agree that it has a vibe of pointing in a more individualistic direction, and it’s worth noticing that and not taking it for granted. But I think the point of Fun Theory is to get at something that really would also underly any good vision for the future, not just one particular one. I think conservatives do actually want complex novelty. I don’t have encyclopedic memory of the Fun Theory sequence but I would bet against it saying anything explicit and probably not even anything implicit about “individual” complex novelty. It even specifically warns against turning our complex, meaningful multiplayer games into single-player experiences)

CEV isn’t about eliminating conflict, it’s (kinda) about efficiently resolving conflict. But, insofar as the resolution of the conflict itself is meaningful, it doesn’t say anything about people not getting to resolve the conflict themselves.

(People seem to be hella downvoting this, and I am kinda confused as to why. I can see not finding it particularly persuasive or interesting. I’m guessing this is just sad tribalism but curious if people have a particular objection I’m missing)

There are some users around who strong-downvote anyone trying to make any arguments on the basis of CEV, and who seem very triggered by the concept. This is sad and has derailed a bunch of conversations in the past. My guess is the same is going on here.

Do you not have the power/tools to stop such behavior from taking effect? This sounds like the exact problem that killed LW 1.0, and which I was lead to believe is now solved.

We have much better tools to detect downvoting of specific users, and unusual voting activity by a specific user, but if a topic only comes up occasionally and the users who vote on that topic also regularly vote on other things, I don’t know of any high-level statistics that would easily detect that, and I think it would have very substantial chilling effects if we were to start policing that kind of behavior.

There probably are technical solutions, but it’s a more tricky kind of problem than what LW 1.0 faced, and we haven’t built them.

I’d be more interested in tools that detected downvotes that occur before people started reading, on the basis of the title—because I’d give even odds that more than half of downvotes on this post were within 1 minute of opening it, on the basis of the title or reacting the the first paragraph—not due to the discussion of CEV.

I was the one who downvoted, and my reasoning for doing this is at a fundamental level, I think a lot of their argument rests on fabrication of options that only appear to work because they ignore the issue of why value disagreement is less tolerable in an AI-controlled future than now.

I have a longer comment below, and @sunwillrise makes a similar point, but a lot of the argument around AI safety having an attitude towards minimizing value conflict makes more sense than the post is giving it credit for, and the mechanisms that allow value disagreements to not blow up into take-over attempts/mass violence relies on certain features of modern society that AGI will break (and there is no talk about how to actually make the vision sustainable):

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/iJzDm6h5a2CK9etYZ/a-conservative-vision-for-ai-alignment#eBdRwtZeJqJkKt2hn

Thank you for noticing the raft of reflexive downvotes; it’s disappointing how much even Lesswrong seems to react reflexively; even the comments seem not to have read the piece, or at least engaged with the arguments.

On your response—I agree that CEV as a process could arrive at the outcomes you’re describing, where ineliminable conflict gets it to throw an error—but think that CEV as approximated and as people assume will work is, as you note, making a prediction that disagreements will dissolve. Not only that, but it asserts that this will have an outcome that preserves what we value. If the tenets of agonism are correct, however, any solution geared towards “efficiently resolving conflict” is destructive of human values—because as we said, “conflict is central to the way society works, not something to overcome.” Still, I agree that Eliezer got parts of this right (a decade before almost anyone else even noticed the problem,) and agree that keeping things as multiplayer games with complex novelty, where conflict still matters is critical. The further point, which I think Eliezer’s fun theory, as written, kind of elides, is that we also need limits and pain for the conflict to matter. That is, again, it seems possible that part of what makes things meaningful is that we need to ourselves engage in the conflict, instead of having it “solved” via extrapolation of our values.

As a separate point, I argued in a different post, we lack the conceptual understanding needed to deal with the question of whether there is some extrapolated version of most agents that is anywhere “close” to their values which is coherent. But at the very least, “the odds that an arbitrary complex system is pursuing some coherent outcome” approaches zero, and that at least slightly implies almost all agents might not be “close” to a rational agent in the important senses we care about for CEV.

I think Eliezer writing says this sort of thing pretty explicitly? (Like, in Three Worlds Collide, the “bad” ending was the one where humans removed all conflict, romantic struggle, and similar types of pain that seem like the sort of thing you’re talking about here)

I assume this will come up later in your sequence, but, as stated this seems way too strong. (I can totally buy that there are qualities of conflict resolution that would be bad to abstract away, but, as stated this is an argument against democracy, markets, mediation, norms for negotiation, etc. Do you actually believe those are destructive of human value and we should be, like, waging war instead of talking? Or do you mean something else here)

I agree that Eliezer has made different points different places, and don’t think that the Fun Theory series makes this clear, and CEV as described seems to not say it. (I can’t try to resolve all the internal tensions between the multiple bookshelves woth of content he’s produced, so I referred to “fun theory, as written.”)

And I certainly don’t think conflict as such is good! (I’ve written about the benefits of avoiding conflict at some length on my substack about cooperation.) My point here was subtly different, and more specific to CEV; I think that solutions for eliminating conflict which route around humans themselves solving the problems might be fundamentally destructive of our values.

I think this might be underestimating how the conservative/liberal axis correlates with scarcity/abundance axis. In an existential struggle against a zombie horde, the conservative policies are a lot more relevant—of course “our tribe first” is the only survivable answer, anybody who wants to “find themselves” when they are supposed to be guarding the entrance is an idiot and a traitor, deviating from proven strategies is a huge risk, etc. When all important resources are abundant, liberal policies become a lot more relevant—hoarding resources, and not sharing with neighbors is a mental illness, there is low risk in an kinds of experimentation and rule breaking, etc. Well, AI is very likely to drastically move us away from scarcity and towards abundance, so need to consider how it affects which policies would make more sense.

That makes a huge number of assumptions about the values and goals of the AI, and is certainly not obvious—unless you’ve already assumed things about the shape of the likely future, and the one we desire. But that’s a large part of what we’re questioning.

How about this—in most non-disaster scenarios, AI would make the abundance a lot easier to achieve. And conservative or liberal, it’s basic human nature to go for abundance in such situations.

I don’t think this is true in the important sense; yes, we’ll plausibly get material abundance, but we will still have just as much conflict because humans want scarcity, and they want conflict. So which resources are “important” will shift. (I should note that Eliezer made something like this point in a tweet, where he said “And yet somehow there is a Poverty Equilibrium which beat a 100-fold increase in productivity plus everything else that went right over the last thousand years”—but his version assumes that once all the necessities are available, poverty would be gone. I think that we view clearly impossible past luxuries, like internet connectivity and access to laundry machines as minimal requirements, showing that the hedonic treadmill is stronger than wealth generation!)

It’s me, by the way. Happy to identify myself.

(I have more agreement than disagreement with the authors on many points, here.)

The big reason why AI safety aims to have a vision of as little disagreement on values as possible between AIs and humans is because the mechanisms that make value disagreement somewhat tolerable (at least in the sense that people won’t kill each other all the time) is going to go away with AGI.

In particular, one of the biggest glues holding our society together is the fact that everyone is dependent on everyone else. Individuals simply can’t thrive without society, and the BATNA is generally so terrible that people will put up with a lot of disagreements to keep themselves away from the BATNA.

In particular, one corollary is that we don’t have to worry much about one individual human subverting the enforcement system, and no one person rules alone. We do have to worry about this for AGI, so a lot of common strategies to manage people breaking agreements do not work.

And the techno-utopian/extinction claims are basically due to the fact that AGI is an extremizing force, in that it allows more and more technological progress allowing access to ever more extreme claims, and would be a convergent result of widely different ideologies.

Putting it less charitably, the post is trying to offer us a fabricated option that is a product of the authors not being able to understand how AI is able to break the constraints of current society, and while I shall wait for future posts, I’m not impressed at all with this first post.

This post is about alignment targets, or what we want an AGI to do, a mostly separable topic from technical alignment, or how we get an AGI to do anything in particular. See my Conflating value alignment and intent alignment is causing confusion for more.

There’s a pretty strong argument that technical alignment is far more pressing, so much so that addressing alignment targets right now really is barely-helpful when compared to doing nothing, and anti-helpful relative to working on technical alignment or “societal alignment” (getting-our-shit-collectively-together).

In particular, those actually in charge of building AGI will want it aligned to their own intent, and they’ll have an excuse because it’s probably genuinely a good bit more dangerous to aim directly at value alignment rather than aim for some sort of long reflection. Instruction-following is the current default alignment target and it will likely continue to be through our first AGI(s) because it offers substantial corrigibility. Value alignment does not, so we have to get it right on the first real try in both technical and the wisdom sense you address here.

More on that argument here.

Yes, this is partly true, but assumes that we can manage technical alignment in a way that is separable from the values we are aiming towards—something that I would have assumed was true before we saw the shape of LLM “alignment” solutions, but no longer think is obvious.

And instruction-following is deeply worrying as an ‘alignment target’, since it doesn’t say anything about what ends up happening, much less actually guarantee corrigibility—especially since we’re not getting meaningful oversight - but that’s a very different argument than the one we’re making here.

I agree that instruction-following is deeply worrying as an alignment target. But it seems it’s what developers will use. Wishing it otherwise won’t make it so. And they’re right that the shape of current LLM alignment “solutions” includes values. I don’t think those are actual solutions to the hard part of the alignment problem. If developers use something like HHH as a major component of the alignment for an AGI, I think that and other targets have pretty obvious outer alignment, failure, modes, and probably less obvious inner alignment problems, so that approach simply fails.

I think in hope that as they approach AGI and take the alignment problem somewhat seriously, developers will try to make instruction following the dominant component. Instruction-following does seem to help non-trivially with the hard part because it provides corrigibility and other useful flexibility. See those links for more.

That is a complex and debatable argument, but the argument that developers will pursue intent alignment seems simpler and stronger. Having an AGI that primarily does your bidding seems safer and more self-interested than one that makes fully autonomous decisions based on some attempt to define everyone’s ideal values.

“This is what’s happening and we’re not going to change it” isn’t helpful—both because it’s just saying we’re all going to die, and because it fails to specify what we’d like to have happen instead. We’re not proposing a specific course for us to influence AI developers, we’re first trying to figure out what future we’d want.

While I’m probably much more of a lib than you guys (at least in ordinary human contexts), I also think that people in AI alignment circles mostly have really silly conceptions of human valuing and the historical development of values.[1] I touch on this a bit here. Also, if you haven’t encountered it already, you might be interested in Hegel’s work on this stuff — in particular, The Phenomenology of Spirit.

This isn’t to say that people in other circles have better conceptions…

Yes, agreed that the concept of value is very often confused, mixing economic utility and decision theory with human preferences, constraints, and goals. Harry Law also discussed the collapse of different conceptions into a single idea of “values” here: https://www.learningfromexamples.com/p/weighed-measured-and-found-wanting

But once you permit an exception for the rule (“okay, today there is no strong reason to do X”), it immediately becomes a precedent (tomorrow: “why do we have to do X, when we didn’t have to do it yesterday?”).

Also, children are quite conservative about the things they like. Try to skip a bedtime story once!

Conservatism isn’t about keeping things as they are. It’s about regression into a gilted fictional past. Intentionally introducing bias into a system in order to transit to a nonexistent temporal location as a reactionary response seems like a strange thing to do in general. It seems like an exceedingly strange thing to do to a conglomeration of logical procedures.

The entire notion is inherently regressive and reactionary. It’s coping with fear of an unknown future by appealing to an idealized past. Intentionally baking fear into the system eliminates the goal of an inherently progressive system that is, by definition and design, intended to be in a continuous state of incremental improvement.

Systematic Utopianism predicated on fictions fabricated in correlation fallacy does not seem like a pursuit of reason; therefore hostile to AGI.

Your dismissive view of “conservatism” as a general movement is noted, and not even unreasonable—but it seems basically irrelevant to what we were discussing in the post, both in terms of what we called conservatism, and the way you tied it to ’Hostile to AGI.” And the latter seems deeply confused, or at least needs much more background explanation.