TL;DR: A holiday obsession turns into a deep meditation on all things pretty. Albatrosses and reward *models* included. Also, check out www.fashionator.xyz (no malware, I promise).

Over the Christmas holiday, I became slightly obsessed with the Netflix show “Next in Fashion.” It’s (probably) only a temporary obsession, nothing to worry about. But before I move on to the next obsession, I wanted to take a moment to write up what I learned[1].

Buckle up, this will be a weird one.

Before I get into the nitty-gritty of my newfound interest in fashion, let me first address the elephant in the room—why care about fashion in the first place[2]?

Why fashion

There are three different schools[3] of thought on the question.

School of the devil: The philosophy of “The Devil Wears Prada[4]” is centered around the idea that fashion is a form of power and influence. The film explores the idea that the fashion industry is a demanding and competitive field that requires a high level of expertise and commitment, and that subverting the rigid hierarchy of fashion can have unintended or unexpected consequences.

School of the barber pole: Scott Alexander’s barber pole model posits that fashion trends move in a predictable cycle, with each new trend allowing elites to distinguish themselves from runner-ups (who take a while to catch up). An important prediction of this model is that fashion worn by the “upper” class can end up looking a lot like fashion worn by the “lower” class, who tend to pick up on trends at a time delay. As such, fashion is primarily a vehicle for signaling social status and group membership.

School of reality TV: While never spelled out explicitly, in “Next in Fashion” fashion is a form of creative expression and a way to appreciate art. The show centers around the skill and talent required to create unique and innovative designs, and the importance of supporting and nurturing new talent in the industry. In this interpretation, fashion can also help us better understand ourselves, each other, and the world we live in.

Why I’m not buying it

But none of these explanations are quite satisfying (or even mutually exclusive). Let’s put them under the microscope one by one.

Is fashion a form of power and influence?

Let’s start with numbers: Global revenue from luxury apparel comes in at US$82.30bn, which is a so-called not-insignificant-number. Thanks to the bird app, the richest person on earth is now the CEO of the world’s largest luxury goods company[5].

Is that actually a big deal? Whenever I see large numbers, I do my best to put them into perspective:

$80 billion is a fair bit more than the ˜US$20bn behind effective altruism charities.

$80 billion might be enough to finance Phase I of the California High-Speed Rail system or one of the smaller departments of the state.

$80 billion is 0.08% of the global GDP—do with that information whatever you like.

Fashion moves money, more so today than yesterday. Classic economic theory is not surprised by that fact, as it literally defines luxury goods as those goods for which “demand increases when a person’s wealth or income increases”. As things generally-tend-to-get-better™, we can expect that (by definition) the amount spent on luxury goods[6] should continue to increase.

Unfortunately, this “truth by definition” also makes the insight vacuous. My question is exactly why luxury clothing is desirable. Fashion implies power, not the other way around. What makes a luxury item luxurious?

Is fashion all about signaling and the slow, cyclical propagation of status markers through society’s ranks?

There certainly is some truth to the barber pole phenomenon. When sources as distinct as SlateStarCodex and CurrentBoutique report the same phenomenon, something real is happening. Fashion trends do come back

However—attributing the cyclical features of fashion to signaling games is… kind of just one possible explanation[7]? And not even a particularly good one, considering that the bigger part of society doesn’t stand in front of their wardrobe thinking about which social class they belong to. The signaling game might still emerge subconsciously (?[8]), but the CurrentBoutique article comes up with a bunch of alternative explanations that don’t require the collaboration of the subliminal. An observation like “TikTokers are raiding their parent’s closets” can explain cyclicality while being well-supported by evidence. No need for a conspiracy and unspoken signaling games.

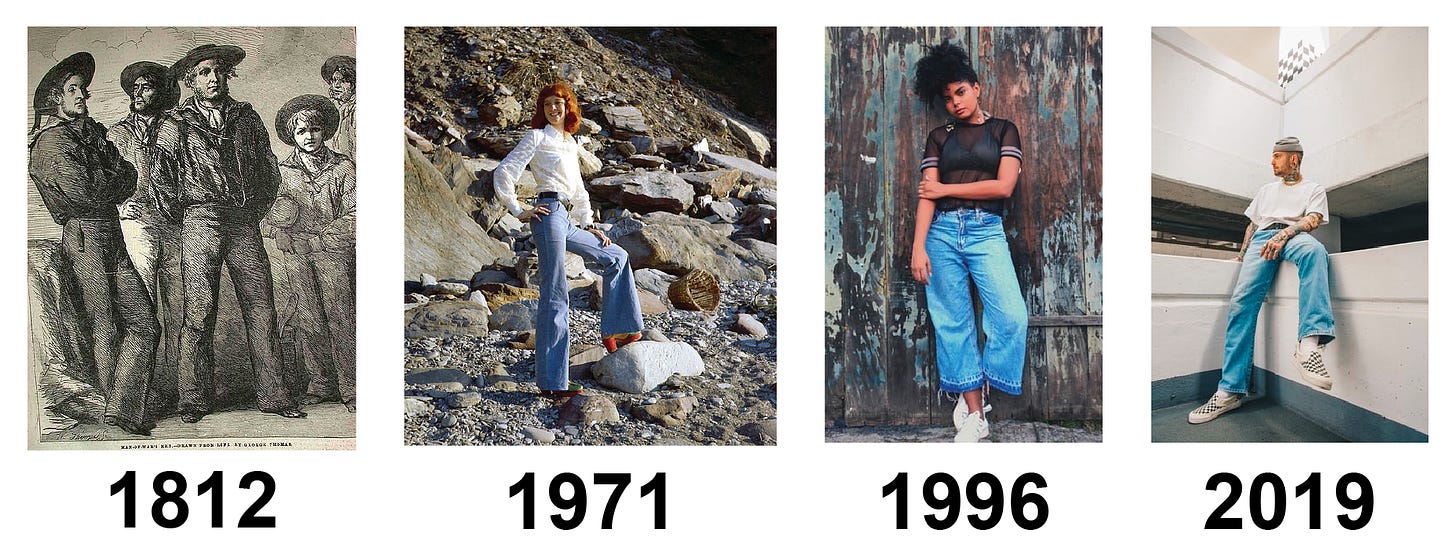

Beyond the objection that signaling games are kind of lame[9], saying “fashion is cyclic” doesn’t explain everything there is to explain. Importantly, fashion doesn’t exactly repeat, each time around.

From pure function, via tight and then baggy fits, all the way to men-sitting-on-appliances. Superficially similar, but higher-order terms do matter.

While the general cuts of fashion tend to return in some form or other, the details matter a lot! In the words of Balaji, all progress is along the z-axis. Bell bottoms keep returning, but something evolves. What is that something? Why do (some) people care?

Is fashion about creative self-expression and art appreciation?

This theory is actually correct. I think ‘fashion can help us better understand ourselves, each other, and the world we live in’ is the true answer. People tend to buy pretty things that are valuable to them and they fit into the big tapestry of everything.

I acknowledge that position is not obviously true without further argument. “Next in fashion” is perfectly positioned to explore this topic, presenting us with a team of designers bubbling over with passion and ambition and a total runtime of 500 minutes[10]. I would love to recommend to you to binge it to learn how fashion sits at the core of everything.

But it falls short of its potential[11]. Don’t get me wrong, the show is entertaining, jam-packed with drama and emotion, and a lot of pretty designs to look at for ~5 seconds each. But the show does not manage to penetrate the core of what draws us to pretty things. It only shows us that some people very clearly are drawn to it.

What I did about it

So now we find ourselves at the center of my holiday obsession.

What makes things pretty? How do people make pretty things?

There is more than one field of academic research that is concerned with that question, but I feel like this type of question must be approached through experiment, not theory. So I aimed to fully submerge myself in the subject matter.

First, I read and watched everything that sparked my interest. The McQueen documentary was revelatory, Bliss Foster on YouTube makes insightful short video essays, and The September Issue gives a more nuanced picture of the fashion industry than “The Devil Wears Prada”.

Second, I studied as I’d study for a test. I’m a big fan of spaced repetition in Roam Research and create new cards for my system at a whim. A single repetition can improve recall dramatically, and—check that out! - it turns out language models are really good at creating spaced repetition cards for you. In my experience, learning about the people and movements in a field can explain a ton of variability.

I had someone quiz me. Language models are very good at that too, but if push comes to shove a fellow human also does the trick. You can even quiz them back.

The Mechanical Anna Wintour

Despite laboring away for multiple days I still felt insecure about my ability to distinguish good from bad fashion. I do however feel rather secure about my ability to train a neural network to learn human preferences. So I threw the experiment strategy out the window, obtained a full scrape of the Vogue Archive, performed object detection to get cutouts of all the outfits, and embedded the cutouts in a semantic vector space with CLIP.

Some kids cut out their favorite outfits from magazines they bought with their lunch money, other kids scrape the vogue archive to get cutouts of all outfits since 1892. You say potato, I say tomato. (I stole that joke from a student of mine).

I then recycled code from an old project and set up a small interface for making judgment calls and storing them in a database.

After forcing kindly asking[12] my significant other to make a measly 1000 comparisons[13], I threw the comparisons into a neural network and trained a reward model. I then ranked the entire dataset and create a montage of the top 15 images.

I am happy to report that she thinks the resulting montage captured her taste pretty well[14]. So I tried to get her to rate 20k additional images, but somehow her enthusiasm for that project diminished quite quickly.

I, however, am not done with this project! The small toy example above demonstrates that fashion sense is not something unquantifiable, but we are still only barely scratching the surface. What is the shape of the fashion landscape? Can we predict fashion trends? How variable is fashion taste across people, and how much of that variability can we explain away?

So I made the website public for you all to try:

https://www.fashionator.xyz/

All your rankings are stored in a database, so I’ll be able to do some fantastic data analysis soon. If you enter your email address, I might send you your top 15 images. And maybe a follow-up survey. Eventually, with sufficient data, I might be able to get to the bottom of what makes beautiful things beautiful. And then, perhaps, I could install a camera in the closet and help me pick my outfits…

Closing words

The holidays have been over for a while, but the finishing touches on this project ended up taking a while. That’s a bummer because I would love to dive deeper into the world of fashion. Knocking out the fashionator app was a ton of fun, and there are so many things I’d like to implement:

integrating a feed of design and fashion pictures, curated by the trained reward model,

guide an image diffusion model with the reward model to generate maximally aesthetic personalized images,

or integrate a search engine to find fashion items similar to those in the user’s closet.

Really, this could keep someone busy for the better part of a work week.

On a more serious note, though, my excursion has not only uncovered wonders and beautiful things. The more cynical take from above (linking the world of fashion with power hierarchies and social signaling) still accurately describes one aspect of the truth. Obsession with fashion also produces a lot of things that are kind of ugly.

I maintain that power and signaling are downstream of what makes fashion desirable[15], but that doesn’t make those ugly inadequacies not exist. Fashion is entangled with power, money, and fame; and thus inaccessible to anyone who doesn’t spend unreasonable amounts of time and money.

There is a possible future where everything goes well. In that world, we might need to think about what humans really want. The thing at the core of fashion, stripped from power-play and signaling games, feels like it could be part of that[16]. Getting a bit closer to that thing made the entire excursion more than worth it for me.

- ^

in the blogging space as writing about Infrabayesianism.

- ^

Isn’t the whole point of moving to the Bay so that you don’t have to care about what you are wearing?

- ^

That I had the patience to spell out

- ^

alright, perhaps my obsession was not limited to a Netflix show

- ^

with luxury clothing producing the largest share of the revenue

- ^

Whatever that might mean in the future.

- ^

Scott probably wouldn’t object. His B-plot with the cellular automata and the fashion is just a set-up for writing about politics—something I will never do! So there’s no territorial dispute here.

- ^

I’m not even sure what consciousness is supposed to mean, the unconscious is certainly above my paygrade.

- ^

See, Scott is not above poking fun at the intrinsic cringiness of signaling games.

- ^

That’s more than 8 hours!

- ^

So instead I recommend watching it as pleasant entertainment!

- ^

Her taste is by far more refined than mine!

- ^

Time flies when you are having fun.

- ^

“Not a color to be seen”

- ^

The most sought-after designs are sought after not (only) because they communicate power, money, and fame, but also because these designs capture something deep about what we as humans care about.

- ^

Remember the definition from economics!

I think you’re under-rating the signaling explanation.

That’s a pretty weak strawman. The bigger part of society DOES stand in front of their wardrobe thinking about what others (and themselves) will think about this visible wardrobe choice, and how it will impact people’s reaction to the wearer.

They probably don’t consciously think in terms of social class, because they’re mostly concerned with peer-signaling (distinctions within their group) than wide-signaling (distinctions among groups). Most people definitely think in terms of “makes me look stuffy or slutty”, “looks like it’s trying too hard”, etc.

One strong comment on the app, the app should present you with a new pair of items rather than keeping the one that you preferred. When I played, after only a handful of selections I got into a local maximum where I liked almost nothing more than the one I had already selected, so I was just pressing the same key over and over through dozens of pictures. This is both less informative and less fun than getting to make a new choice every time.

Additionally: separate mens’ fashion from womens’ fashion if possible.

Hmmm good point. I originally made that decision because loading the image from the server was actually kind of slow. But then I figured out asynchronicity, so could totally change it… I’ll see if I find some time later today to push an update! (to make an ‘all vs all’ mode in addition to the ‘King of the hill’)

This was fun to read. The website was fun to click. I agree that attention to that ineffable thing that might be called “consumer surplus” or “why we like things” is super interestingly important and understudied and related to a lot of “physical object appreciation” issues that are hard to write about.

I’d offer some abstract candidate things that people kinda like:

Bold clean contrasts (something is happening on purpose such that an error would be visibly disruptive).

Symmetry (because duh?).

Joyful colors (like in spring time).

Clicking though your website for labeling I found myself adopting an attitude of looking for something that it would make me actively happy to wear to work in an office, until I got bored of saying the same thing was great over and over and over.… and clicked on something I’d love to wear to a party. Then pretty fast I imagine I have to go back to work and slowly hill climbing through “preferable to wear to work vs a party dress (or the previous thing)” until I found a great work outfit again.

(As I did it, my data will exhibit circular preferences, I’m pretty sure. If there was a way to add a “salient as great” label, and change this when I change my mood or see a thing that calls to me and causes me to want a new label, then I think (or would like to imagine? or aspire to be such that...) my preference ordering under each label would be well ordered.)

I imagined you trying to train a visual model of “what Jennifer likes” (that wasn’t massively pre-trained to capture coherent articulate semantics from the images) and it didn’t seem likely to work… I don’t think I was picking things based on trivial 2D visual rules?

A lot of it was “oh I love the skirt and hate the top, but the outfit is better than my current best (like: I’d buy the outfit to keep the skirt)” and then “oh that top’s sleeves are fantastic, and the pants are tolerable” and so on.

I kind of expect MY labeling has a bunch of latent dimensions, and that everyone else’s clicking is also full of other dimensions (but also dimensions I care about) and that it would be really interesting to see the dimensional analysis, and a read out of my relative weights on the dimensions that your tool could identify.

If I have a guest ID, can I send it to you here and get outputs somehow, or do I have to start over my clicking and sign in if I want that?

Hi Jennifer!

Awesome, thank you for the thoughtful comment! The links are super interesting, reminds me of some of the research in empirical aesthetics I read forever ago.

On the topic of circular preferences: It turns out that the type of reward model I am training here handles non-transitive preferences in a “sensible” fashion. In particular, if you’re “non-circular on average” (i.e. you only make accidental “mistakes” in your rating) then the model averages that out. And if you consitently have a loopy utility function, then the reward model will map all the elements of the loop onto the same reward value.

Finally: Yes, totally, feel free to send me the guest ID either here of via DM!

Interesting! I’m fascinated by the idea of a way to figure out the transitive relations via a “non-circular on average” assumption and might go hunt down the code to see how it works. I think humans (and likely dogs and maybe pigeons) have preference learning stuff that helps them remember and abstract early choices and early outcomes somehow, to bootstrap into skilled choosers pretty fast, but I’ve never really thought about the algorithms that might do this. It feels like stumbling across a whole potential microfield of cognitive science that I’ve never heard of before that is potentially important to friendliness research!

(I have sent the DM. Thanks <3)