A new year has come. It’s 2024 and note-taking isn’t cool anymore. The once-blooming space has had its moment. Moreover, the almighty Roam Research isn’t the only king anymore.

The hype is officially over.

At this time of year, when many are busy reflecting on the past year while excitingly looking into the future, I realized it’s a good opportunity to look back at Roam’s madness timeline. The company that took Twitterverse and Silicon Valley by storm is now long after its breakthrough.

Roam was one of those phenomena that happen every other few years. Its appearance in our lives not only made the “tools for thought” niche fashionable. It marked a new era in the land of note-taking apps. In conjunction with a flourishing movement of internet intellectuals[1], it sparked a tsunami of new tools.

Followed by a cult of believers, Roam’s growth was meteoric. It quickly joined the exclusive million ARR club and raised money from notable investors while reaching a soaring valuation. It was living the dream.

In the post-mortem of the note-taking mania, Roam’s hype was replaced by dramas, scandals, and rants questioning its future. Although Roam is still very much alive and kicking, its legacy can already be seen.

The Roam effect

2020 is best known for the breakout of a historic pandemic. In the parallel tech universe, it was also the year when note-taking apps went off the charts, and not only by user surging. The buzz of Roam ignited a fresh discourse among productivity enthusiasts.

In the prehistoric era before Roam, the green giant elephant of Evernote had long dominated the somewhat sleepy note-taking space. The awakening moment came shortly after Notion entered the world, capturing the attention of an industry.

After we’ve learned how to build a second brain[2] in Notion, it was time to move forward to more advanced concepts. The rise of Roam popularized quirky terms like Memex, and Zettelkasten to a broader audience.

Apart from Roam’s rapid growth, it was the beginning of a golden age for PKM fanatics. A rise of internet intellectuals brought topics like Evergreen Notes, and Digital Gardens to the forefront.

The small niche soon turned into a vibrant community. At one point it seemed everyone had become zealous note-takers. Roam, the community’s beloved, sparked dual engagement, leading to its discovery and reshaping the note-taking space.

Outlining the outline

Taking notes usually happens in the form of bullet points. It’s one of the most effective ways to extract thoughts into a written or typed word. Whether during a meeting or a self-brainstorming session, it’s likely to find yourself jotting down notes in a bullet list.

The bullet point doesn’t need an introduction. It’s an ancient convention for everyday tasks like to-dos and grocery lists. However, it went under the radar in modern software, as Jordan Moore tweeted once:

I’ve been pondering on the reasons why. I figured one might be related to its unappealing shape: plain, boring, and repetitive. A bullet point feels like a raw material, an atomic unit:

Atoms are the basic building blocks of all matter. Each chemical element has distinct properties, and they can’t be broken down further without losing their meaning.

Modern design thinking (sorry, not this) would probably try hard to manipulate and overdesign the bullet point pattern until it embodies legitimate 21st-century aesthetics. Its wide acceptance across many communities is completely dissonant with mainstream design culture. It’s not surprising that Roam had its first baptism of fire within niche researchers’ communities and not in tech communities such as designers or seasoned SV founders.

Popular document-based tools like Notion and Coda have built their products with a visual approach. Notion popularized not only the .so domain but also introduced a new way of writing and creating web pages. Prompting a command menu by typing ”/” to insert built-in widgets like image galleries or rich data tables now seems ubiquitous in software across many fields. From conducting research to creating forms online—tools like Tally, Linear, Craft, and Dovetail are only a few that joined this movement in recent years.

Although borrowing the same slash-to-command feature, Roam embraced a more unconservative approach. It replaced buttons with [[weird syntax]], repurposed the sidebar, and popularized the term “graph” in a non-database context.

As Dan Shipper put it:

The underlying genius of Roam is that it is structured not like a tool, but like a programming language.

Indeed Roam is very much inspired by a niche programming language called Clojure. Furthermore, it’s built with it. It’s a flexible, small syntax language imparting a plasticine feeling. One can achieve many things using a small amount of building blocks. Much like Roam.

Over the past few years, we’ve seen a growing number of productivity and note-taking apps. Like Roam, they are all document-centric, with an editor at the heart of their products. Yet, they reside in a distant corner of the matrix.

Notion and Co. are all focused on workplace collaboration like task management and shared knowledge bases, packaged in a multiplayer experience. In the pure field of note-taking apps, there are Bear and Drafts which take a more classic vibe, like Apple Notes.

On the other hand, Roam focuses heavily on the text experience. Designed for personal use, it provides a unique freeform experience.

At its core, Roam is an Outliner—a bullet list structured software. Exploring the origins[3]

Read more: 1) Yury Molodtsov, The Evolution of Outliners 2) Wörtergarten, A history of outliners of Outliners goes way back to the 1980s when Dave Winer worked on ThinkThank. In contemporary software, Workflowy and later Dynalist are seen as evangelists for popularizing the outlining system. Despite its long history, Outliners remained a tiny niche.

Roam’s extreme minimalist design might look simple on the surface. It suggests a simple, even dull interface to work in. As with any other Outliner, its main component is a bullet point.

Over the last decade, we’ve seen “complex” design patterns evolve. The infinite canvas, chatbot interface, and even the command line have become omnipresent in today’s tools. Compared to bullet points, these patterns are more appealing: sleek, and playful to use. Interacting with an interface through the act of drawing, or chatting might be more satisfying than typing bullet points over and over again. These patterns offer instant and rich feedback whereas bullet points are less immersive.

One of the things Roam excels at is remixing ideas—turning old ideas into modern art. A prime example is the revival of bi-directional linking, an idea first described as “associative trails” in Vannevar Bush’s 1945 essay “As We May Think”. In his work, Bush imagined the Memex, a futuristic device allowing individuals to store, access, and link information. The Memex would serve as a personal knowledge base through associative indexing:

The owner of the memex, let us say, is interested in the origin and properties of the bow and arrow… First he runs through an encyclopedia, finds an interesting but sketchy article, leaves it projected. Next, in a history, he finds another pertinent item, and ties the two together. Thus he goes, building a trail of many items. Occasionally he inserts a comment of his own, either linking it into the main trail or joining it by a side trail to a particular item. When it becomes evident that the elastic properties of available materials had a great deal to do with the bow, he branches off on a side trail which takes him through textbooks on elasticity and tables of physical constants. He inserts a page of longhand analysis of his own. Thus he builds a trail of his interest through the maze of materials available to him.

A decade and a half later, Ted Nelson began working on a hypertext system, known as “Project Xanadu”. Influenced by Bush’s work, Nelson prototyped a digital library where all kinds of documents could be found, anywhere in the world. Unlike Bush, Nelson’s idea was to create a collective repository of information rather than a personal one. In Nelson’s version, associative indexing was called “zippered lists”, or more famously “transclusion”:

These zippered lists would allow compound documents to be formed from pieces of other documents

Project Xanadu, Wikipedia

While being influential in the development of the World Wide Web, both projects fell short of their original visions. In hindsight, they might be considered instances of technology being ahead of time.

Nevertheless, it had to take a few more decades for the same idea to resurface again. In the Roam version, associative indexing is called bi-directional linking, and it’s an important core part of the experience.

Inspired by nvALT, Roam borrowed the notation of [[double-bracket]] to link between entries. The experience is akin to writing a self-dictionary, where each entry gets a unique interpretation. Anything that goes between the brackets automatically becomes a link to a standalone page. Each page references every instance of the same “dictionary entry”.

This workflow enables resurfacing entire or partial entries. Roamers might add new comments, thoughts, or contexts as they remix existing pages or paragraphs into new entries. A modern Memex.

On nonlinear-ism

Traditionally, modern software is designed in a linear structure. Notably known as the “workspace”— a popular file cabinet structure, that reminds the parent-child relationship. Working in this structure conveys a feeling of playing a “pass the parcel” game. Every time you open a folder, the next one is revealed.

All this makes sense, as linearity is a human structure. From supermarket shopping to life skill courses, experiences are designed in a linear, progression path. The common streak pattern can be seen from afar in mediation apps, online coding courses, and learning apps.

Additionally, software follows a structured sequence. Starting with a sign-up and onboarding flow, such experiences are designed to walk the customer through a defined path. While trying to avoid the “blank page problem”, they become schematic.

And yet, Roam had challenged this approach.

After signing up, it seems like you get dropped into the deep water without any buoy[4]. Although learning Roam is a gradual journey, its opinionated editor design features only a daily-titled entry on a blank canvas.

It’s the “blank page problem” in its all glory.

Unlike most software, Roam is non-linear by nature. The fundamental essence of Roam is the ability to log entries and reference them over time. Roam acts as a time machine, allowing exploration across past, present, and seemingly future entries.

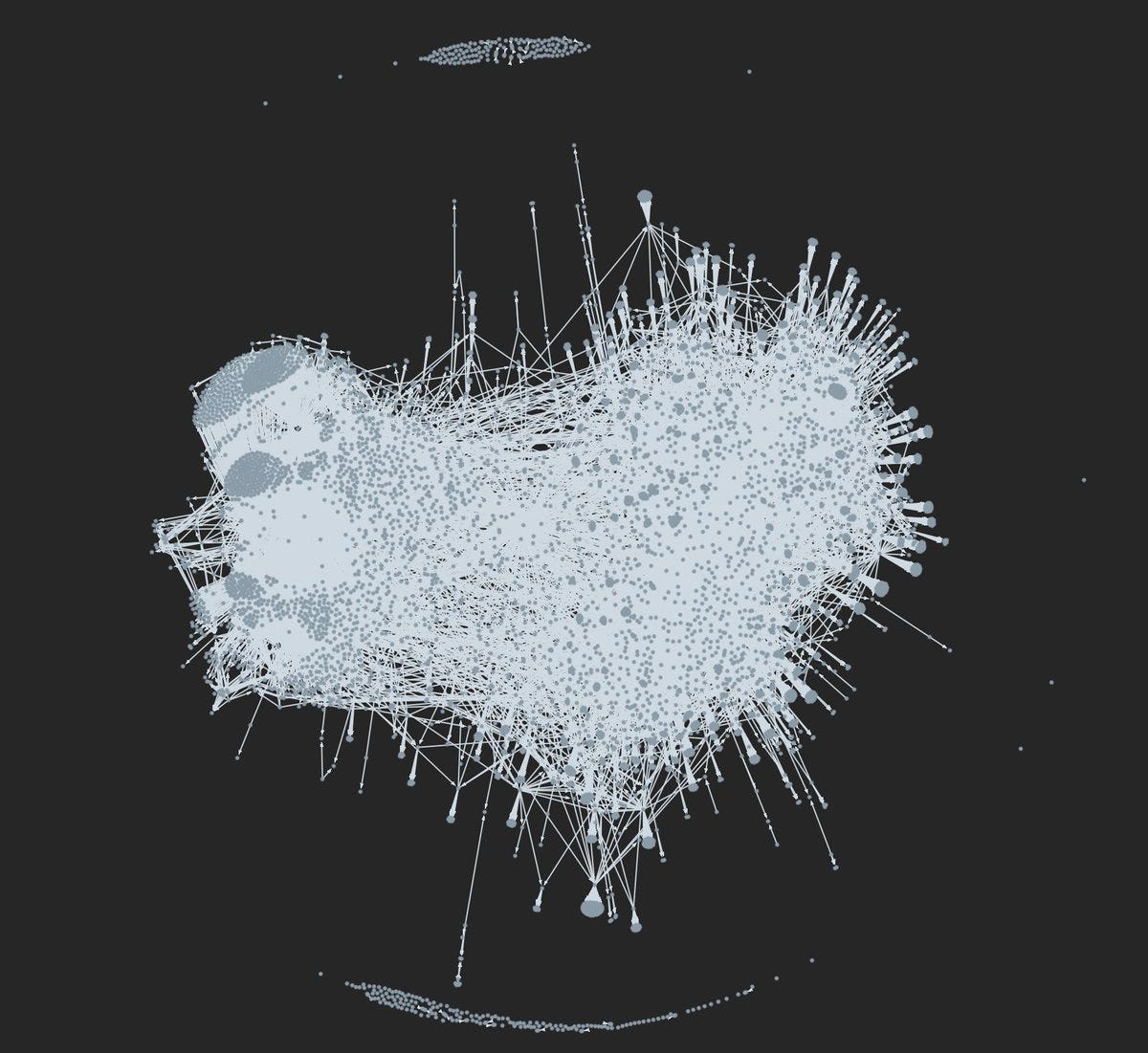

The Roam workspace is called a knowledge graph, and it takes a different approach. There’s no top-down hierarchy. There are no nested folders. Entried turns to pages, which live on the same level. Pages are treated as nodes, and their relationships are determined by how they are linked to each other.

These nodes become overwhelming very fast. Piles of texts get stacked and pages become scattered, conveying a sense of losing control. I remember this odd feeling just from visiting Roam’s homepage for the first time.

At the time, taking notes in the Roam-way required adapting a new mental model. Learning the formatting and syntax was challenging, even for tech-savvies. Roam might have chosen a more standard onboarding to ease that pain, but I suspect grasping Roam is more of a cognitive rather than a usability barrier.

Leaving the “I need to first understand this product’s benefits” approach outside the scope might be derived as a result of prioritization. However, it did fuel the FOMO with a burst of tutorials, courses, and workshops of live onboarding sessions.

Mastering Roam involves a daunting learning curve, not just in terms of the hours invested but in the depth and complexity of the knowledge required. In that sense, Roam reminds the process of learning a new skill, rather than a product. It involves understanding many new concepts and acquiring knowledge. It demands patience, more than a simple onboarding process of a few seconds or minutes.

After the “fall”

Roam popularized the networked thinking method, transforming it from an unheard-of niche to a widespread practice. It led people to switch from the librarian to the gardener mode, advocating a manifesto switching away from Evernote.

Roam’s impact echoed through many different spheres. The overall excitement around it and its un-boarding led people to become advocates.

Nat Eliason created the famous “Effortless Output” course and sold it like hot-(expensive)-cakes at the time. Before productivity gurus like Ali Abdaal and Thomas Frank began making tutorial videos, people like Shu Omi has leveraged Roam’s rise to start a YouTube career.

The rumor about an exciting new tool quickly spread. It had fulfilled the dream of any Silicon Valley-based startup: becoming recognized by the upper class. Kevin Rose, Patrick Collison, Venkatesh Rao, Erik Torenberg, Jeff Morris Jr. , and visakan veerasamy were among the first investors and customers.

However, its success created a vacuum. As a company that drew so much attention, it developed high expectations from the vast crowd. Once Roam started to feel stale, fans turned into vocal critics. Rants have been discussing Roam’s performance, product development, and even its co-founder’s personality.

A massive influx ensued as people abandoned the allegedly sinking ship to find others to jump onto. Ironically, it was Roam that paved the way for alternatives. As soon as Roam gained traction, it proved there was room for more networked thinking tools. A growing list of Outliners integrated with bi-directional linking started to appear like mushrooms after the rain.

Many seized the opportunity to build alternatives focused on different approaches. A landscape map can be drawn out only from a few of them: Athens Research (RIP), and Logseq took the open-source direction. Reflect focused on trendy UX and more advanced features. Obsidian was built with a local-first principle, while Subconscious has taken the blockchain/protocol approach.

Long live the bullet list!

Yet, the decline of Roam’s popularity isn’t tied only to its seeming lack of growth or scale. In other posts writers

Casey Newton and Dan Shipper describe a shared experience. It seems to be a misalignment between the tool and its premise:

But the original promise of Roam — that it would improve my thinking by helping me to build a knowledge base and discover new ideas — fizzled completely.

Casey Newton, Why note-taking apps don’t make us smarter

At least for me—and most of the people I know—we got a garbage dump full of crufty links and pieces of text we hardly ever revisit.

Dan Shipper, The Fall of Roam

Even famous Nat Eliason once tweeted that he went full circle back to analog notes.

From a personal standpoint, I can relate to this notion. I’ve never been an avid note-taker. The least I do is open the Apple Notes app or sketch down ideas and wireframes in my sketchbook. Finding a systematic way to capture thoughts and ideas was never my thing. It always seemed too rigorous to me. And as a non-university graduate, methods like GTD or PARA sound like academic courses I should avoid.

I did spend a few long months using Roam. Similarly to Shipper’s experience, I ended up with a beautiful mess of a gigantic amount of information. However, as I mentioned before, figuring out how to use Roam requires a mental adaptation. Navigating a sea of text blocks isn’t a fit for everyone. I also remember that humanities and STEM subjects are two different expertise, for two types of people.

When software lacks a soul

I rant quite a lot about the current state of product design in tech. It’s one of the topics that most interest me. It’s also a big source of motivation for writing this very own publication.

Finding a soul as a product today seems rare in software. The rise of CSS frameworks like Tailwind and others has lowered the bare minimum entry for making a good-looking design. It made life easier but at the same time seemed to degenerate people’s creativity. Alongside trends that come and go, many products and websites look very much the same.

More profoundly there’s this idea of smallness I adore, once brought to my attention by designer Ben Pieratt:

What I’ve noticed since leaving Svpply is that other industries treat their 1% differently. In the fashion or magazine industries for instance, they give the creative output of their star members their full attention. The 1% is the whole thing. There’s no open invitation to contribute content to Monocle.

With hindsight, I feel the reason Svpply never grew into anything substantial is because we misread the opportunity. Smallness was the steam that drove our engine and we opened the gasket.

The familiar social network pattern is to aspire to convert the whole world into a member.

We think there’s room for a different approach. A social network that’s both niche and healthy. A social network that’s more magazine than platform.

The desire to build an empire, instead of a small village is one of the biggest evils in tech. For many startup founders, the holy grail is to achieve the hockey stick—an ethos that has long been spreaded by VCs and tech veterans.

User declining might be a negative metric for showing in investor updates. However, in some cases, such a scenario can be quite healthy for a product to sustain. Roam’s fall may not be that genuine after all. I wonder whether it’s just the narrative that plays into the hands of VC-like minds and traditional publications that chase after these kinds of “failures”.

Looking from a distance of 12,000 km might be deceptive, but the smallness thesis seems to apply to Roam[5]. Eliminating the noise is a good quality for any software, especially after a super-hype that everyone wants to be a part of. It only makes sense that not all of Roam’s early adopters were the right audience: even the greatest evangelists who seemingly made a fortune out of the hype, or those who were most recognized with it.

Backlinks might have become a convention that’s here to last, but writing a {{query: {or: [[using]] [[components]] }}} isn’t for everyone. But that’s largely part of Roam’s soul. Productivity aficionados and note-taking enthusiasts, particularly in the Roam style are a very specific niche. In a recent post, members of the Roam community praised the “lack of new features”, or “it still looks like 2020” as a feature, not a bug[6]. It seems that Roam found its true believers, and not just those who once purchased a Believer plan and canceled it. Roam’s community may have shrunk, but it remains strong.

Despite new successors having taken the lead in the ever-lasting competition of note-taking apps, Roam remains unique. From day one it didn’t look like a Tailwind-themed website. It didn’t incorporate big drop-shadow buttons or trendy animations. Others might be flashier, elegant, or shinier, but Roam’s uniqueness is reflected by how it doesn’t “fit” the conventional design model. Conor, Roam’s co-founder once summed up this view in response to an unsolicited redesign of Roam’s homepage:

From the beginning, there was something about Roam’s simplicity. It wasn’t been aligned with what people used to see. The monotony of its homepage and “boring” colors reflected a sense of boredom. It felt naive but in a good way.

It didn’t look like a copycat.

Instead, Roam was, and still just being itself.

- ^

People like Maggie Appleton, Tom Critchlow, Andy Matuschak, and Anne-Laure Le Cunff

- ^

The term was coined by Tiago Forte

- ^

Read more: 1) Yury Molodtsov, The Evolution of Outliners 2) Wörtergarten, A history of outliners

- ^

The static, floating ”?” icon is available, but it doesn’t serve as a guiding tour toward a defined path.

- ^

I’m well aware of the fact Roam is a VC-backed company. However, from the outside, it seems that despite being “driven” by other interests, it takes a different approach, which is not growth at all costs.

- ^

Is there an alternative to constantly adding endless features? Can software be designed to operate without daily updates, similar to programming languages?

I have to say, I still don’t understand the cult of Roam or why people were so impressed by, eg. the

[[link]]syntax borrowed from English Wikipedia (which introduced it something like 18 years before on what is still the most widely-read & edited wiki software in history), which you remark on repeatedly. Even in 2019 in beta it just seemed like a personal wiki, not much different from, say, PmWiki (2002) with some more emphasis than usual on the common backlink or ‘reverse citation’ functionality (that so many hypertext systems had supported going back decades in parallel with Xanadu ideas). It may be nicer than, say, English Wikipedia’s “WhatLinksHere” (which has been there since before I began using it early in the 2000s), but nothing to create a social-media cult over or sell “courses” about (!).But if the bubble has burst, it’s not hard to see why: any note-taking, personal knowledge management, or personal wiki system is inherently limited by the fact that they require a lot of work for what is, for most people, little gain. For most people, trying to track all of this stuff is as useful as exact itemized grocery store receipts from 5 years ago.

Most people simply have no need for lots of half-formed ideas, random lists of research papers, and so on. This is what people always miss about Zettelkasten: are you writing a book? Are you a historian or German scholar? Do you publish a dozen papers a year? No? Then why do you think you need a Zettelkasten? If you are going to be pulling out a decent chunk of those references for an essay or something, possibly decades from now, then it can be worth the upfront cost of entering references into your system, knowing that you’ll never use most of them and the benefit is mostly from the long tail, and you will, in the natural course of usage, periodically look over them to foster serendipity & creativity; if you aren’t writing all that, then there’s no long tail, no real benefit, no intrinsic review & serendipity, and it’s just a massive time & energy sink. Eventually, the user abandons it… and their life gets better.

Further, these systems are inherently passive, and force people to become secretaries, typists, reference librarians, archivists, & writers simply to keep it from rotting (quite aside from any mere software issue), to keep it up to date, revise tenses or references, fix spelling errors, deal with link rot, and so on. (Surprisingly, most people do not find that enjoyable.) There is no intelligence in such systems, and they don’t do anything. The user still has to do all the thinking, and it adds on a lot of thinking overhead.

So what comes after Roam and other personal systems which force the user to do all the thinking? I should think that would be obvious: systems which can think for the user instead. LLMs and other contemporary AI are wildly underused in the personal system space right now, and can potentially fix a lot of these issues, through approaches like actively surfacing connections instead of passively waiting for the user to make them on their own and manually record them, and can proactively suggest edits & updates & fixes that the user simply approves in batches. (Think of how much easier it is to copyedit a document using a spellcheck as a series of Y/N semi-automatic edits, than to go through it by eye, fixing typos.)

However, like most such paradigm shifts, it will be hard to tack it onto existing systems. You can’t reap the full benefits of LLMs with some tweaks like ‘let’s embed documents and add a little retrieval pane!’. You need to rethink the entire system and rewrite it from the ground up on the basis of making neural nets do as much as possible, to figure out the new capabilities and design patterns, and what to drop from the old obsolete personal wikis like Roam.

From what it sounds like, the Roam community would never stand for that, and I have a lot of doubts about whether it makes sense economically to try. It seems like if one wanted to do that, it would be better to start with a clean sheet (and an empty cap table).

Fernando Boretti has a good 2022 post “Unbundling Tools for Thought” I don’t think I saw before, but which makes some of these points at greater length and I largely agree with.

Adding to my reading list, thanks.

Not sure exactly what’s meant by roam community but Subconscious are thinking about that stuff. I forget what exactly they’re doing with it, I haven’t been paying attention to it (maybe I’m the roam community), but I think it was something like… it goes and surfaces something from the past to remind you of it to make sure things you might have forgotten about get linked together. (Gosh that would be bad for my productivity.)

Subconscious sounds like a different codebase and group, which is not paying any money to Roam, so I would define it as ‘not the Roam community’ and illustrating the problem for anyone who wants to do a startup on ‘Roam 2’.

From my personal perspective, I think Roam brought to attention a different type of software and vibe which were dominated SV type startups. Through Roam, I’ve learned about all those fancy-old ideas and concepts. I guess I was coming from a more mainstream corner of the tech scene.

My excitement declined as the hype too, and as you describe, I couldn’t understand its real benefits as I didn’t have a strong enough reason to use it.

Coming to Roam a few years later, after starting a publication, has made the difference as I’m less focused on [[double-bracketing]] but just taking notes, gradually and only when I’m feeling like it.

As I’ve tried to explain over and over, including once to Conor, if you want to improve thinking (rather than, say, “knowledge management” (text snippet / link management?)), you have to watch thinking think, think about how thinking thinks, and ask thinking what it would need in order to think better. No one who sets out to build so-called “tools for thinking” ever does this. They instead think of cool-sounding things to have, and then get excited imagining how those things might free your thoughts from the nested directory structure or whatever, and come up with unassailable arguments about that.

I am interested in all the ways we could improve our thinking. It was my initial impression that Andy Matuschak’s Tools for Thought seem to aim at this, and I was convinced by his Evergreen Notes thesis. You’re probably already familiar with his work.

Can I get your input on why current note-taking systems fail at supporting at thinking and some alternatives? Or if note-taking itself is missing the point, how can we augment good thinking?

That’s a big question, like asking a doctor “how do you make people healthy”, except I’m not a doctor and there’s basically no medical science, metaphorically. My literal answer is “make smarter babies” https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/jTiSWHKAtnyA723LE/overview-of-strong-human-intelligence-amplification-methods , but I assume you mean augmenting adults using computer software. For the latter: the only thing I think I know is that you’d have to all of the following steps, in order:

Become really good at watching your own thinking processes, including/especially the murky / inexplicit / difficult / pretheoretic / learning-based parts.

Become really really good at thinking. Like, publish technical research that many people acknowledge is high quality, or something like that (maybe without the acknowledgement, but good luck self-grading). Apply 0.

Figure out what key processes from 1. could have been accelerated with software.

Thank you for the response.

Any physical or mental system meant to improve thinking and cognition for anyone right now. One obvious example is writing, which extends our capacity to think and remember. Another would be SRS, which helps solidify our memory.

But your reply points at the more important inner mental systems. Sadly, I don’t know any simple, obvious way to do the 0th step.

In hindsight, LW is all about the 0th step.

These days, I’ve left both traditional and roam-like note-taking apps behind because they all left me with collections of half finished notes on ideas/writings that I would seldomly revisit again. Instead I started to just use Anki for all my note-taking. It’s not made for this use case, but it is part of my daily workflow anyway and it solves my biggest problem of stale notes by making me revisit them regularly.

With Anki I record any fleeting ideas as standalone notes, without an “answer” component. Later, when these note come up for review I spend a few moments to refine each idea. This keeps the notes dynamic and evolving. If the idea turns into something promising, I’ll add an item on my normal ToDo list for some dedicated in-depth exploration of this idea. Conversely, if the idea seems like a dead end, I’ll suspend it so it is not shown anymore during review.

The feature I’m missing most is being able to easily link to related notes. Anki’s notes can be grouped into decks, and tagged, but I find jumping to the note browser and entering search terms cumbersome.

Example of the note-taking workflow: I have an idea of an Anki feature which would automatically link related notes to each other, and e. g. show the links at the bottom of each answer card. I suspect that text embeddings could help there. So I add a note “Using text embeddings for automatic Anki note linking” to my Ideas deck. The next time this card is shown during review I might edit it to add “Implement as an Anki plugin that will regularly run on and update all notes in the collection” and the next time maybe some thought about an implementation detail like ”? how to make sure that the links it placed in the note by the plugin are ignored for embedding purposes”.

It seems like the anki for notetaking is https://www.remnote.com/ ? Suggested here https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/CoqFpaorNHsWxRzvz/what-comes-after-roam-s-renaissance?commentId=9LY2cTTAKbaJsBCNf

I’m using a different but similar approach of incorporating SRS into Roam instead ( https://vlad.roam.garden/apply-Spaced-Repetition-to-evergreen-notes-that-you-want-to-remember-or-periodically-rise-to-attention ).

I’m still on Roam and using it every day. For me, it’s not “a lot of work”, it’s what’s necessary to keep track of my thoughts to the point that I feel like my mental workspace is clean. I’ve journaled a lot since I was a kid. I think better in writing.

This is my permanent diary. I will probably have it for the rest of my life, if they keep supporting it. Twenty years from now, I’ll want to know what I was doing today!

I also log literally all links of “general interest” in my browsing history in my public Roam. does anyone care? Probably not, but it matters to me.

Roam doesn’t make me smarter. To be honest, in my current life I don’t especially need to be smarter. But I do think it makes me more consistent and coherent. It helps me realize when I’ve had a thought before, and what thoughts I keep coming back to. It helps me “listen to my own voice”, which is an antidote to peer pressure. And it helps me see change over time—what things I’ve said in the past that seem foolish now, how long it takes me to emotionally process things (sometimes years!), etc.

Just want to plug my 2019 summary of the book that started it all.

How to take smart notes (Ahrens, 2017) — LessWrong

It’s a good book, for sure. I use Logseq, which is similar to Roam but more fitted to my habits. I never bought into the Roam hype (rarely even heard of it), but this makes me glad I never went into it.

I think the whole roam fad may have been an example of a phenomenon I’m noticing where these fundamentally social apes that we are cannot conceive of an activity failing to become social, the idea that what I see isn’t what others see, or the idea that there are activities that can’t be shared, is unnatural and unintuitive to us. Roam would have made a lot of sense as a new kind of social network oriented around collaboratively, iteratively building evergreen knowledge together, and it vibed like it was that, and I think that’s why there was so much excitement, but due to the way Roam works and the shoddy way it was built, it actually couldn’t grow into that. The human sense for social fun isn’t smart enough to notice that it wasn’t going to happen and so it took a long time to wind down.

Specifically, multiplayer roam has no notification system, and it’s siloed into groups. They don’t have per-block/per-page read/write permissions, meaning that you kind of have to be sharing all of the notes in a graph or none of them, and as far as I’m aware there are no communities that makes sense for. Most peoples’ notes end up being mostly private, rough or intimate.

But massively multiplayer roam as a concept is totally possible, it just has to be built in a different way, with different systems.

It’s one of the things I want to build.

For me, some stuff fell into disrepair when I realized no one else was going to read it or add to it, which I think is mostly due to a bad model for shared use, but a lot of other stuff kept growing and turned out to be really transformative. I’ve continued using it as a very good, very long todo list, a pensieve to relinquish and defer burdensome thoughts into, to sort every possible idea I could be pursuing and to prioritize the one currently most important thing.

Some other pages that’ve remained active over the years:

recipes

tasteweb engineering notes, pitch concepts

UFO stuff (some interesting evidence, but mostly debunkings). I guess this could add up to a post eventually.

“people”, a list of various things to talk about with people next time we’re in a room together, if we ever are. The uncertainty, that we may not meet, is the reason I think it’s important to externalize these thoughts.

Subconscious isn’t blockchain. The noosphere protocol has the foundational features of a smart contract system, but it doesn’t seem quite secure enough against inconsistencies/double-spends to run finance (and that’s not an aspiration they seem to have), and the sacrifices it makes will make it cheap and easy to scale horizontally/federate. The protocol it’s most similar to is bluesky’s ATProtocol. I actually wanted to complain to them that they’re too similar and they should merge, but noosphere started developing before ATProtocol existed, so who can blame them really.

Although a part of me does wonder, if a protocol like atproto took off, whether people would start doing finance on it, security be damned, and then legal enforcement and auditing would come along and it would be effectively secured through international social technologies and trusted computing instead of cryptographic technologies and game theory and we might just end up in the same place. It would be a weird future.

Strong evaporative cooling of group beliefs vibes.

No one mentioned Remnote? It’s the one Roam replacer that seems to beat Roam on many of the things it was good at.

I way prefer remote storage, having lost a hard drive before, so I don’t like Obsidian much.

There’s tana https://twitter.com/AndyAyrey/status/1791679301362016519?t=Wo8e4NcWJqY4pcHRjMYgAQ&s=19

“daily” in “daily updates” is hyperbole, but you can probably get most of the way there with

a subscription-based model (annual and/or monthly)

periodic updates to ensure it works properly when the underlying platform changes (like when Apple adds dark mode to its OS and exposes this to websites with

prefers-color-scheme).The second bullet point is important, at least occasionally. I dropped my beloved VoodooPad because it never got a publicly-released version that supports dark mode that works on macOS, iOS, and iPadOS. I figure VoodooPad is nearly dead because its current owners can’t figure out how to turn it into something that gets enough revenue to justify the time that it would take to make it a modern app.

At any rate, the notes I had in VoodooPad got moved into Ulysses some time after the Ulysses team added projects back in 2022. Ulysses is not a good personal wiki (internal linking isn’t nearly as low-friction as in Obsidian), but it’s adequate for my purposes and I dislike having a gazillion different personal-wiki software packages that I need to divvy my attention between.

As far as update cadence goes…

If you look at Ulysses’ Releases page and make note of the dates in the headings, you can see that they’ve been steadily, but not all that quickly, been releasing features. There’s probably at least one programming language out there with this release cadence, but I wouldn’t know which one it is.