My journey to the microwave alternate timeline

Cross-posted from Telescopic Turnip

Recommended soundtrack for this post

As we all know, the march of technological progress is best summarized by this meme from Linkedin:

Inventors constantly come up with exciting new inventions, each of them with the potential to change everything forever. But only a fraction of these ever establish themselves as a persistent part of civilization, and the rest vanish from collective consciousness. Before shutting down forever, though, the alternate branches of the tech tree leave some faint traces behind: over-optimistic sci-fi stories, outdated educational cartoons, and, sometimes, some obscure accessories that briefly made it to mass production before being quietly discontinued.

The classical example of an abandoned timeline is the Glorious Atomic Future, as described in the 1957 Disney cartoon Our Friend the Atom. A scientist with a suspiciously German accent explains all the wonderful things nuclear power will bring to our lives:

Sadly, the glorious atomic future somewhat failed to materialize, and, by the early 1960s, the project to rip a second Panama canal by detonating a necklace of nuclear bombs was canceled, because we are ruled by bureaucrats who hate fun and efficiency.

While the Our-Friend-the-Atom timeline remains out of reach from most hobbyists, not all alternate timelines are permanently closed to exploration. There are other timelines that you can explore from the comfort of your home, just by buying a few second-hand items off eBay.

I recently spent a few months in one of these abandoned timelines: the one where the microwave oven replaced the stove.

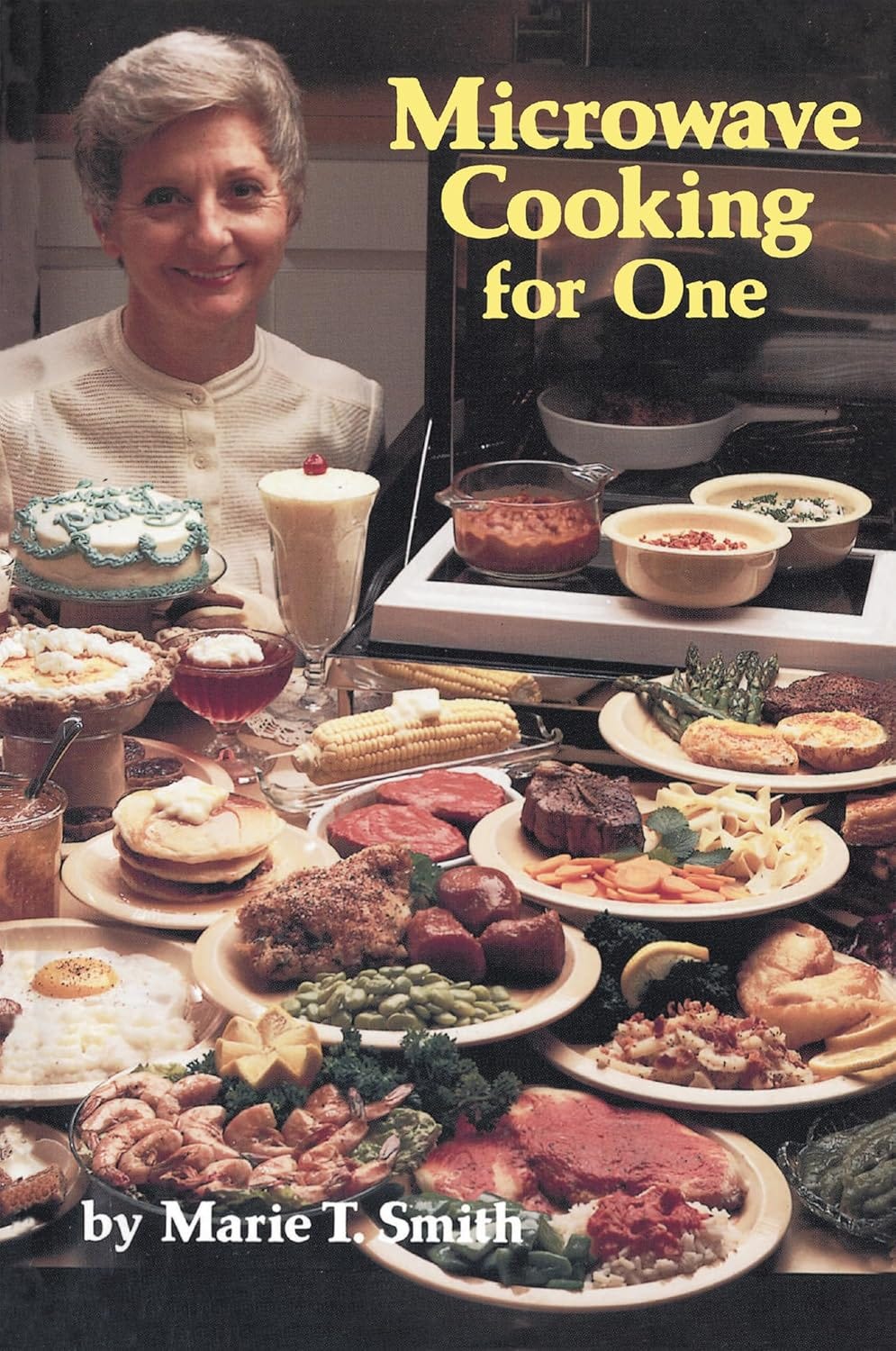

First, I had to get myself a copy of the world’s saddest book.

Microwave Cooking, for One

Marie T. Smith’s Microwave Cooking for One is an old forgotten book of microwave recipes from the 1980s. In the mid-2010s, it garnered the momentary attention of the Internet as “the world’s saddest cookbook”:

To the modern eye, it seems obvious that microwave cooking can only be about reheating ready-made frozen food. It’s about staring blankly at the buzzing white box, waiting for the four dreadful beeps that give you permission to eat. It’s about consuming lukewarm processed slop on a rickety formica table, with only the crackling of a flickering neon light piercing through the silence.

But this is completely misinterpreting Microwave Cooking for One’s vision. Two important pieces of context are missing. First – the book was published in 1985. Compare to the adoption S-curve of the microwave oven:

When MCfO was published, microwave cooking was still a new entrant to the world of household electronics. Market researchers were speculating about how the food and packaging industries would adapt their products to the new era and how deep the transformation would go. Many saw the microwave revolution as a material necessity: women were massively entering the workforce, and soon nobody would have much time to spend behind a stove. In 1985, the microwave future looked inevitable.

Second – Marie T. Smith is a microwave maximalist. She spent ten years putting every comestible object in the microwave to see what happens. Look at the items on the book cover – some are obviously impossible to prepare with a microwave, right? Well, that’s where you’re wrong. Marie T. Smith figured out a way to prepare absolutely everything. If you are a disciple of her philosophy, you shouldn’t even own a stove. Smith herself hasn’t owned one since the early 1970s. As she explains in the cookbook’s introduction, Smith believed the microwave would ultimately replace stove-top cooking, the same way stove-top cooking had replaced campfire-top cooking.

So, my goal is twofold: first, I want to know if there’s any merit to all of these forgotten microwaving techniques. Something that can make plasma out of grapes, set your house on fire and bring frozen hamsters back to life cannot be fundamentally bad. But also, I want to get a glimpse of what the world looks like in the uchronia where Marie T. Smith won and Big Teflon lost. Why did we drift apart from this timeline?

Out of the frying pan, into the magnetron

Before we start experimenting, it’s helpful to have a coarse intuition of how microwave ovens work. Microwaves use a device called a magnetron to emit radiation with wavelengths around 5-10 cm, and send it to bounce around the closed chamber where you put your food. The idea that electromagnetic radiation can heat stuff up isn’t particularly strange (we’ve all been exposed to the sun), but microwaves do it in an odd spooky way. Microwaves’ frequency is too low to be absorbed directly by food molecules. Instead, it is just low enough that, in effect, the electric field around the molecules regularly changes direction. If the molecules have a dipole moment (as water does), they start wiggling around, and the friction generates plenty of heat.

As far as I can tell, this kind of light-matter interaction doesn’t occur to a noticeable degree anywhere on Earth, except in our microwave ovens. This is going to be important later: the microwave is weird, and it often behaves contrary to our day-to-day intuitions. (For example, it’s surprisingly hard to melt ice cubes in the microwave. This is because the water molecules are locked in a lattice, so they can’t spin as much as they would in a liquid.) Thus, to tame the microwave, the first thing we’ll need is an open mind.

With that in mind, let’s open the grimoire of Microwave Cooking for One and see what kind of blood magic we can conjure from it.

The book cover, with its smiling middle-aged woman and its abundance of provisions, makes it look like it’s going to be nice and wholesome.

It’s not going to be nice and wholesome.

Microwave cooking is not about intuition. It’s about discipline. The timing and the wattage matter, but so do the exact shape and size of the vessels. Smith gives us a list of specific hardware with exceedingly modern names like the Cook’n’Pour® Saucepan or the CorningWare™ Menu-ette® so we can get reproducible results. If you were used to counting carrots in carrot units, that has to stop – carrots are measured in ounces, with a scale, and for volume you use a metal measuring cup. Glass ones are simply too inaccurate for where we are going.

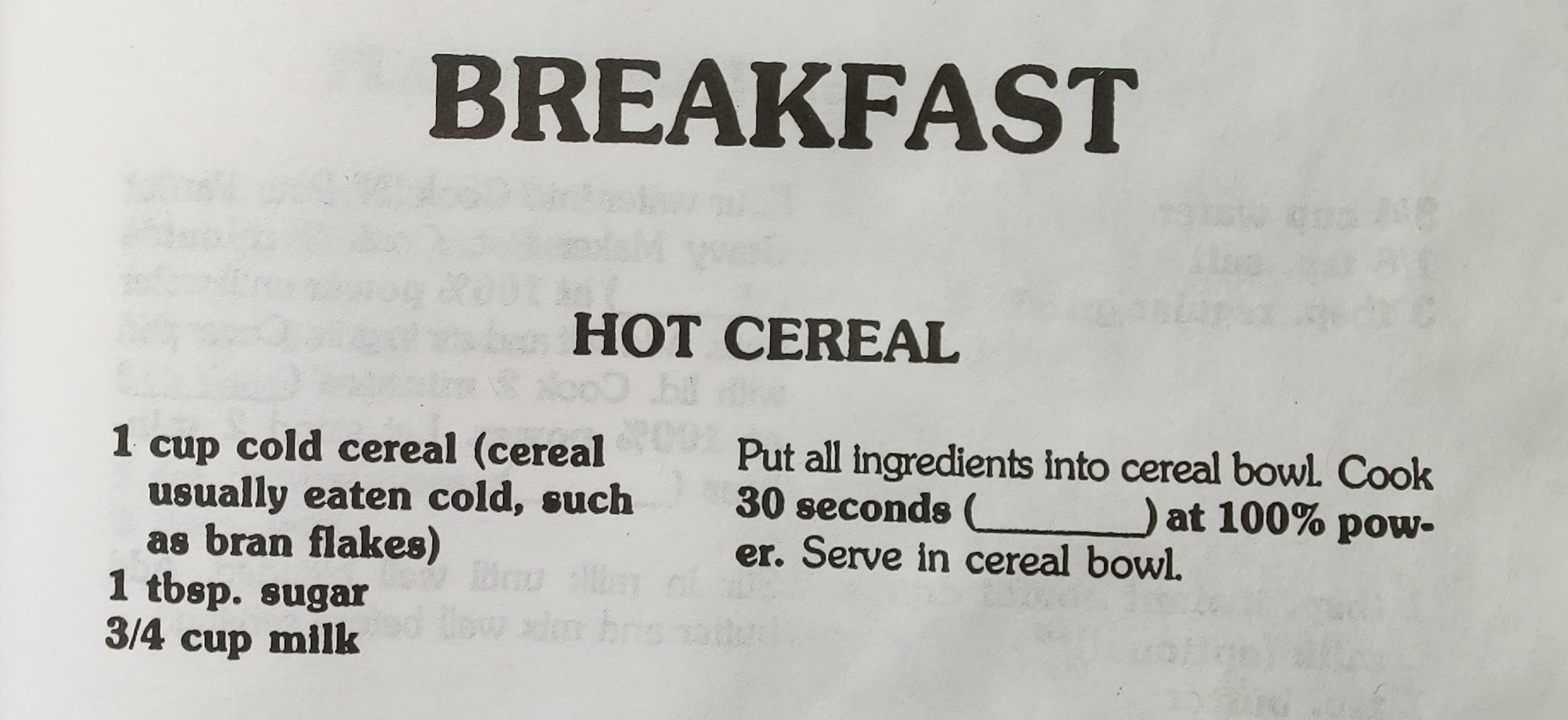

The actual recipe section starts with the recipe for a bowl of cereal, which I am 70% sure is a joke:

Whenever a cooking time is specified, Smith includes “(____)” as a placeholder, so you can write in your own value, optimized for your particular setup. If your hot cereal is anything short of delicious, you are invited to do your own step of gradient descent.

A lot of recipes in the book involve stacking various objects under, above, and around the food. For vegetables, Smith generally recommends slicing them thinly, putting them between a cardboard plate and towel paper, then microwaving the ensemble. This works great. I tried it with onion and carrots, and it does make nice crispy vegetables, similar to what you get when you steam the vegetables in a rice cooker (also a great technique). I’d still say the rice cooker gives better results, but for situations where you absolutely need your carrots done in under two minutes, the microwave method is hard to beat.

But cardboard contraptions, on their own, can only take us this far. They do little to overcome the true frontier for microwave-only cooking: the Maillard Reaction.Around 150°C, amino acids and sugars combine to form dark-colored tasty compounds, also known as browning. For a good browning, you must rapidly reach temperatures well above the boiling point of water. This is particularly difficult to do in a microwave – which is why people tend to use the microwave specifically for things that don’t require the Maillard reaction.

But this is because people are weak. True radicals, like Marie T. Smith and myself, are able to obtain a perfectly fine Maillard reaction in their microwave ovens. All you need is the right cookware. Are you ready to use the full extent of microwave capabilities?

Tradwife futurism

In 1938, chemists from DuPont were trying to create a revolutionary refrigerant, when they accidentally synthesized a new compound they called teflon. It took until the early 1950s for the wife of a random engineer to suggest that teflon could be used to coat frying pans, and it worked. This led to the development of the teflon-coated frying pan.

In parallel, in 1953, chemists from Corning were trying to create photosensitive glass that could be etched using UV light, when they accidentally synthesized a new compound they called pyroceram. Pyroceram is almost unbreakable, extremely resistant to heat shocks, and remarkably non-sticky. Most importantly, the bottom can be coated with tin oxide, which enables it to absorb microwave radiation and become arbitrarily hot. This led to the development of the microwave browning skillet.

In the stove-top timeline where we live, the teflon-coated pan has become ubiquitous. But in the alternate microwave timeline, nobody has heard of teflon pans, and everybody owns a pyroceram browning skillet instead.

I know most of you are meta-contrarian edgelords, but nothing today will smash your Overton window harder than the 1986 cooking TV show Good Days, where Marie T. Smith is seen microwaving a complete cheeseburger on live TV using such a skillet.

I acquired mine second-hand from eBay and it quickly became one of my favorite objects. I could only describe its aesthetics as tradwife futurism. The overall design and cute colonial house drawings give it clear 1980s grandma vibes, but the three standoffs and metal-coated bottom give it a strange futuristic quality. It truly feels like an object from another timeline.

The key trick is to put the empty skillet alone in the microwave and let it accumulate as much heat as you desire[1] before adding the food. Then, supposedly, you can get any degree of searing you like by following the right sequence of bleeps and bloops.

According to Marie Smith, this is superior to traditional stove-top cooking in many ways – it’s faster, consumes less energy, and requires less effort to clean the dishes. Let’s try a few basic recipes to see how well it works.

You’ll microwave steak and pasta, and you’ll be happy

Let’s start with something maximally outrageous: the microwaved steak with onions. I’d typically use olive oil, but the first step in Smith’s recipe is to rub the steak in butter, making this recipe a heresy for at least three groups of people.

The onions are cooked with the veggie cooking method again, and the steak is done with a masterful use of the browning skillet.

I split the meat in two halves, so I could directly compare the orthodox and heretical methods.[2] The results were very promising. It takes a little bit of practice to get things exactly right, but not much more than the traditional method. The Pyroceram pan was about as easy to clean as the Teflon one. I didn’t measure the energy cost, but the microwave would probably win on that front. So far, the alternate timeline holds up quite well.

As a second eval, I tried sunny-side up eggs. On the face of it, it’s the simplest possible recipe, but it’s surprisingly hard to master. The problem is that different parts of the egg have different optimal cooking temperatures. Adam Ragusea has a video showcasing half a dozen techniques, none of which feature a microwave.

What does Marie Smith have to say about this? She employs a multi-step method. Like with the steak, we start by preheating the browning skillet. Then, we quickly coat it with butter, which should instantly start to boil. This is when we add the egg, sprinkle it lightly with water, and put it back in the oven for 45 (___) seconds. (Why the water sprinkling? Smith doesn’t explain. Maybe it’s meant to ensure the egg receives heat from all directions?)

Here again, I was pleased with the result – I’d go as far as saying it works better than the pan. With that success, I went on to try the next step of difficulty: poached eggs.

Poached eggs are my secret internal benchmark. Never in my life have I managed to make proper poached eggs, despite trying every weird trick and lifehack I came across. Will MCfO break my streak of bad luck?

Like for veggies, the egg is poached in the middle of an assemblage of multiple imbricated containers filled with specific amounts of water and pre-heated in a multi-step procedure. We are also told that the egg yolk must be punctured with a fork before cooking. (What happens if you don’t? The book doesn’t say, and I would rather not know.)

The recipe calls for 1 minute and 10 seconds of cooking at full power. Around the 1 minute and 5 seconds mark, my egg violently exploded, sending the various vessels to bounce around the walls of the oven. And listen, as I said, I came to this book with an open mind, but I expect a cookbook to give you at least enough information to avoid a literal explosion. So I wrote “LESS” in the “(____)” and never tried this recipe again.

The rest of the book is mostly made of variations of these basic methods. Some recipes sound like they would plausibly work, but were not interesting enough for me to try (for example, the pasta recipes primarily involve boiling water in the microwave and cooking pasta in it).

All in all, I think I believe most of the claims Smith makes about the microwave. Would it be possible to survive in a bunker with just a laptop, a microwave and a Cook’n’Pour SaucePan®? I think so. It probably saves energy, it definitely saves time washing the dishes, and getting a perfect browning is entirely within reach. There were failures, and many recipes would require a few rounds of practice before getting everything right, but the same is true for stove-top cooking.

On the other hand, there’s a reason the book is called Microwave Cooking for One and not Microwave Cooking for a Large, Loving Family. It’s not just because it is targeted at lonely losers. It’s because microwave cooking becomes exponentially more complicated as you increase the number of guests. I am not saying that the microwave technology in itself cannot be scaled up – if you really want to, it can:

you are not a true pro-natalist

But these industrial giant microwaves are processing a steady stream of regular, standard-sized pieces of food. Homecooking is different. Each potato comes in a different size and shape. So, while baking one potato according to MCfO’s guidance is easy and works wonderfully, things quickly get out of hand when you try baking multiple potatoes at the same time. Here is the sad truth: baking potatoes in the microwave is an NP-hard problem. For a general-purpose home-cooking technology, that’s a serious setback.

The weird thing is, the microwave maximalists of the 1980s got the sociology mostly right. People are preparing meals for themselves for longer and longer stretches of their lives. Women are indeed spending less time in the kitchen. The future where people cook For One – the one that was supposed to make the microwave timeline inevitable, arrived exactly as planned. And yet, the microwave stayed a lowly reheating device. Something else must be going on. Maybe the real forking path happened at the level of vibes?

Microvibes

To start with the obvious, the microwave has always been spooky, scary tech. Microwave heating was discovered by accident in 1945 by an engineer while he was developing new radar technologies for the US military. These are the worst possible circumstances to discover some new cooking tech – microwave manufacturers had to persuade normal civilians, who just watched Hiroshima on live TV, to irradiate their food with invisible electromagnetic waves coming from an object called “the magnetron”. Add that to the generally weird and counterintuitive behavior of food in the microwave, and it’s not surprising that people treated the device with suspicion.

Second, microwave cooking fell victim to the same curse that threatens every new easy-to-use technology: it became low-status tech. In Inadequate Equilibria, Eliezer makes a similar point about velcro: the earliest adopters of velcro were toddlers and the elderly – the people who had the most trouble tying their shoes. So Velcro became unforgivably unfashionable. I think a similar process happened with microwaves. While microwave ovens can cook pretty much any meal to any degree of sophistication, the place where they truly excel is reheating shitty canned meals, and soon the two became inseparable in the collective mind, preventing microwaves from reaching their full potential for more elaborate cuisine.

Third, compared to frying things in a pan, microwave cooking is just fundamentally less fun. I actually enjoy seeing my food transform into something visibly delicious before my eyes. But microwave cooking, even when done perfectly right, gives you none of that. You can still hear the noises, but not knowing what produced them makes them significantly more ominous. Some advanced recipes in MCoF call for 8 minutes at full power, and 8 minutes feel like a lot of time when you are helplessly listening to the monstrous anger of the oil, the stuttering onions’ rapid rattle, and the shrill, demented choirs of wailing pork ribs.

With all that said, I do think Microwave Cooking for One is an admirable cookbook. The recipes are probably not the finest cuisine, but they’ll expand your cooking possibilities more than any other recipe book.[3] What I find uniquely cool about Marie T. Smith is that she started with no credentials or qualifications: she was a random housewife who simply fell in love with a new piece of technology, spent a decade pushing it to its limits, and published her findings as a cookbook. Just a woman and a magnetron. You can just explore your own branch of the tech tree!

Let’s not oversell it – if your reference class is “tech visionaries”, maybe that’s taking it a bit too far. If your reference class is “Middle-aged Americans from the eighties who claim they can expand your horizons using waves”, then Marie T. Smith is easily top percentile.

- ^

To illustrate the fact that things can get really hot in a microwave oven, here is a tutorial for smelting metals in the microwave. You just need a graphite crucible and very tolerant roommates.

- ^

For maximum scientific rigor, I should have done a blind comparison, but I didn’t – in part because I’m lazy, in part because asking someone else to do the blinding feels like breaking the rules. It’s microwave cooking For One. I must face it alone. It is my journey.

- ^

My main complaint with Microwave Cooking for One is that it doesn’t have an entry for “birthday cake”. Come on Marie, you had one job.

This feels like a throwback to the LW of yore in an excellent way. Bravo.

My general philosophy on cooking is “if it can’t be cooked it in the microwave, then I ain’t cooking it”, so this post is right up my alley!

I’m guessing you never tried to cook eggs in a microwave before. The exploding egg problem is relatively well known. The typical solution is to puncture the egg to release the steam that builds up between the white and the yolk, since that’s what causes the explosion. They even sell special dishes for making poached eggs in the microwave.

Also, pasta is incredibly easy to cook in the microwave. Again, they sell a special dish for it, which is basically just a long plastic rectangle so you can cook long noodles. Shorter noodles are also allowed. The main challenge is keeping the thing from boiling over, which can be achieved with a combination of salted water, oil, and not trying to cook too much at once. Pasta will cook in water that’s not at a roiling boil, though it takes longer, but the end result is about the same.

Rice, potatoes, carrots, and lots of other things are also quite easy to cook in the microwave. Even fish is pretty easy to cook in one, although I don’t recommend it because it makes a lot of fish smell (unless you like that).

One of the most fun LW posts I’ve read in a while, thanks a lot for writing it!

What recipe would you recommend for someone who doesn’t have a microwave browning skillet? I’d like to try it, but I don’t want to purchase a skillet until I’ve tasted the potential myself.

I laughed so hard through most of this, good writing!

I would venture that the problem is not the microwave, it’s that this is not a natural set of methods for humans. I expect my hypothetical circa 2045 household robots to handle a lot of cooking in ways that maximize efficiency beyond what this human would want to bother with.

This was a super fun read! Especially with the recommended soundtrack.

I recently found some vegan pork buns that are ready after 4 minutes in the microwave. They come in microwave safe plastic, that kinda looks like a cup holder from a fast food place. You fill the bottom with a little bit of water before putting them in.

On the day my partners and I discovered them, we ate both packets in one sitting, then went back to the store and bought another 5 packets, and ate another 3 that day. Microwaves are incredible! People need to know this!

I currently live somewhere with just a microwave and hotplate, so this is intriguing to me. One question—when Marie says “100% power” in a cookbook from 1985, do you need to tone it down somewhat for modern microwaves?

Source for the “meme from LinkedIn”: https://x.com/waitbutwhy/status/1367871165319049221

I need instructions for finding a microwave browning skillet in a non English speaking county, where Corningware might not have existed.