Response to nostalgebraist: proudly waving my moral-antirealist battle flag

@nostalgebraist has recently posted yet another thought-provoking post, this one on how we should feel about AI ruling a long-term posthuman future. [Previous discussion of this same post on lesswrong.] His post touches on some of the themes of Joe Carlsmith’s “Otherness and Control in the Age of AI” series—a series which I enthusiastically recommend—but nostalgebraist takes those ideas much further, in a way that makes me want to push back.

Nostalgebraist’s post is casual, trying to reify and respond to a “doomer” vibe, rather than responding to specific arguments by specific people. Now, I happen to self-identify as a “doomer” sometimes. (Is calling myself a “doomer” bad epistemics and bad PR? Eh, I guess. But also: it sounds cool.) But I too have plenty of disagreements with others in the “doomer” camp (cf: “Rationalist (n.) Someone who disagrees with Eliezer Yudkowsky”.). Maybe nostalgebraist and I have common ground? I dunno. Be that as it may, here are some responses to certain points he brings up.

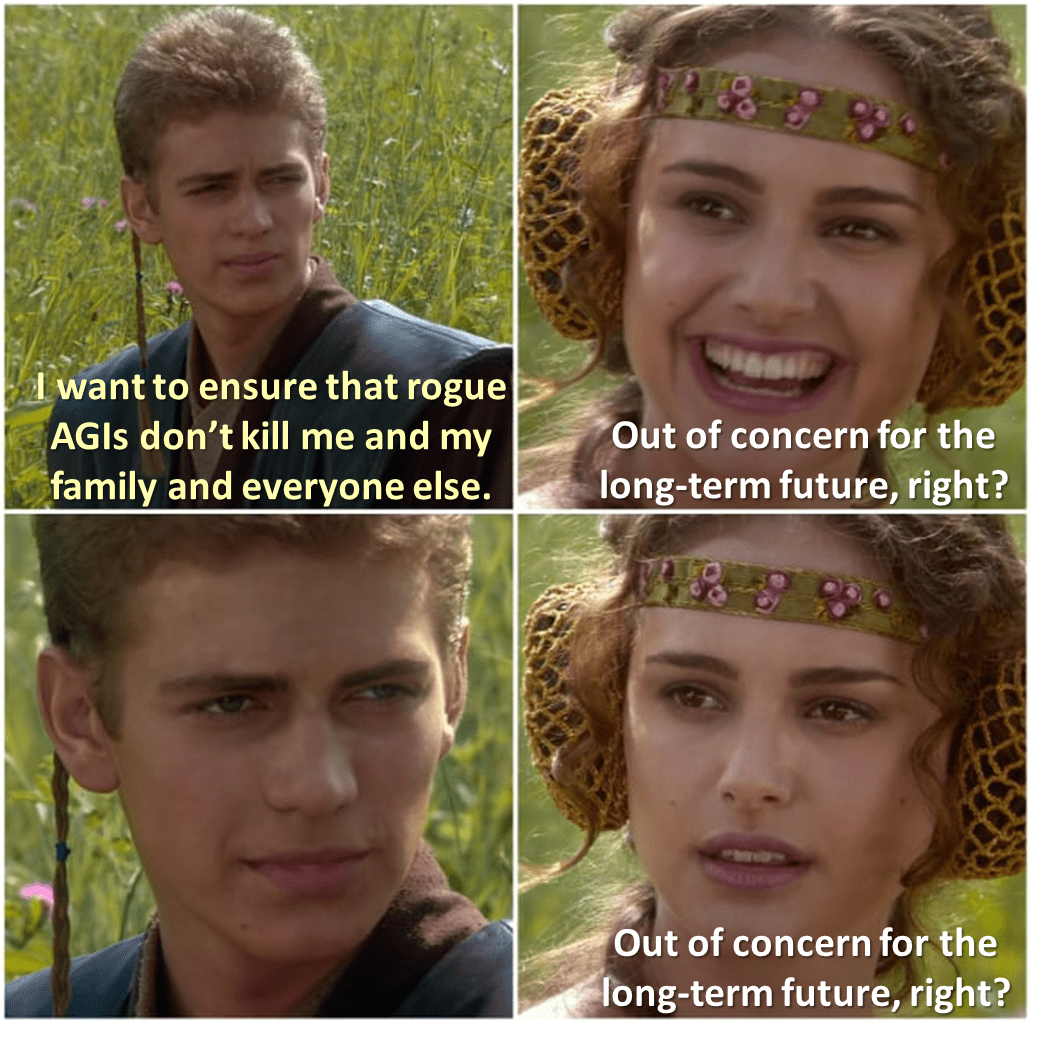

1. The “notkilleveryoneism” pitch is not about longtermism, and that’s fine

Nostalgebraist is mostly focusing on longtermist considerations, and I’ll mostly do that too here. But on our way there, in the lead-in, nostalgebraist does pause to make a point about the term “notkilleveryoneism”:

They call their position “notkilleveryoneism,” to distinguish that position from other worries about AI which don’t touch on the we’re-all-gonna-die thing. And who on earth would want to be a not-notkilleveryoneist?

But they do not mean, by these regular-Joe words, the things that a regular Joe would mean by them.

We are, in fact, all going to die. Probably, eventually. AI or no AI.

In a hundred years, if not fifty. By old age, if nothing else. You know what I mean.…

OK, my understanding was:

(1) we doomers are unhappy about the possibility of AI killing all humans because we’re concerned that the resulting long-term AI future would be a future we don’t want; and

(2) we doomers are also unhappy about the possibility of AI killing all humans because we are human and we don’t want to get murdered by AIs. And also, some of us have children with dreams of growing up and having kids of their own and being a famous inventor or oh wait actually I’d rather work for Nintendo on their Zelda team or hmm wait does Nintendo hire famous inventors? …And all these lovely aspirations again would require not getting murdered by AIs.

If we think of the “notkilleveryoneism” term as part of a communication and outreach strategy, then it’s a strategy that appeals to Average Joe’s desire to not be murdered by AIs, and not to Average Joe’s desires about the long-term future.

And that’s fine! Average Joe has every right to not be murdered, and honestly it’s a safe bet that Average Joe doesn’t have carefully-considered coherent opinions about the long-term future anyway.

Sometimes there’s more than one reason to want a problem to be solved, and you can lead with the more intuitive one. I don’t think anyone is being disingenuous here (although see comment).

1.1 …But now let’s get back to the longtermist stuff

Anyway, that was kinda a digression from the longtermist stuff which forms the main subject of nostalgebraist’s post.

Suppose AI takes over, wipes out humanity, and colonizes the galaxy in a posthuman future. He and I agree that it’s at least conceivable that this long-term posthuman future would be a bad future, e.g. if the AI was a paperclip maximizer. And he and I agree that it’s also possible that it would be a good future, e.g. if there is a future full of life and love and beauty and adventure throughout the cosmos. Which will it be? Let’s dive into that discussion.

2. Cooperation does not require kindness

Here’s nostalgebraist:

I can perhaps imagine a world of artificial X-maximizers, each a superhuman genius, each with its own inane and simple goal.

What I really cannot imagine is a world in which these beings, for all their intelligence, cannot notice that ruthlessly undercutting one another at every turn is a suboptimal equilibrium, and that there is a better way.

Leaving aside sociopaths (more on which below), humans have (I claim) “innate drives”, some of which lead to them having feelings associated with friendship, compassion, generosity, etc., as ends in themselves.

If you look at the human world, you might think that these innate drives are absolutely essential for cooperation and coordination. But they’re not!

For example, look at companies. Companies do not have innate drives towards cooperation that lead to them intrinsically caring about the profits of other companies, as an end in themselves. Rather, company leaders systematically make decisions that maximize their own company’s success.[1] And yet, companies cooperate anyway, all the time! How? Well, maybe they draw out detailed contracts, and maybe they use collateral or escrow, and maybe they check each other’s audited account books, and maybe they ask around to see whether this company has a track record of partnering in good faith, and so on. There are selfish profit-maximizing reasons to be honest, to be cooperative, to negotiate in good faith, to bend over backwards, and so on.

So, cooperation and coordination is entirely possible and routine in the absence of true intrinsic altruism, i.e. in the absence of any intrinsic feeling that generosity is an end in itself.

I concede that true intrinsic altruism has some benefits that can’t be perfectly replaced by complex contracts and enforcement mechanisms. If nothing else, you have to lawyer up every time anything changes. Theoretically, if partnering companies could mutually agree to intrinsically care about each others’ profits (to a precisely-calibrated extent), then that would be a Pareto-improvement over the status quo. But I have two responses:

First, game theory is a bitch sometimes. Just because beings find themselves to be in a suboptimal equilibrium, doesn’t necessarily mean that this equilibrium won’t happen anyway. Maybe the so-called “suboptimal equilibrium” is in fact the only stable equilibrium.

Second, the above is probably moot, because it seems very likely to me that sufficiently advanced competing AIs would be able to cooperate quite well indeed by not-truly-altruistic contractual mechanisms. And maybe they could cooperate even better by doing something like “merging” (e.g. jointly designing a successor AI that they’re both happy to hand over their resources to). None of this would involve any intrinsic feelings of friendship and compassion anywhere in sight.

So again, beings that experience feelings of friendship, compassion, etc., as ends in themselves are not necessary for cooperative behavior to happen, and in any case, to the extent that those feelings help facilitate cooperative behavior, that doesn’t prove that they’ll be part of the future.

(Incidentally, to respond to another point raised by nostalgebraist, just as AIs without innate friendship emotions could nevertheless cooperate for strategic instrumental reasons, it is equally true that AIs without innate “curiosity” and “changeability” could nevertheless do explore-exploit behavior for strategic instrumental reasons. See e.g. discussion here.)

3. “Wanting some kind of feeling of friendship, compassion, or connection to exist at all in the distant future” seems (1) important, (2) not the “conditioners” thing, (3) not inevitable

I mentioned “leaving aside sociopaths” above. But hey, what about high-functioning sociopaths? They are evidently able to do extremely impressive things, far beyond current AI technology, for better or worse (usually worse).

Like, SBF was by all accounts a really sharp guy, and moreover he accomplished one of the great frauds of our era. I mean, I think of myself as a pretty smart guy who can get things done, but man, I would never be able to commit fraud at 1% as ambitious a scale as what SBF pulled off! By the same token, I’ve only known two sociopaths well in my life, and one of them skyrocketed through the ranks of his field—he’s currently the head of research at a major R1 university, with occasional spells as a government appointee in positions of immense power.

Granted, sociopaths have typical areas of incompetence too, like unusually-strong aversion to doing very tedious things that would advance their long-term plans. But I really think there isn’t any deep tie between those traits and their lack of guilt or compassion. Instead I think it’s an incidental correlation—I think they’re two different effects of the same neuroscientific root cause. I can’t prove that but you can read my opinions here.

So we have something close to an existence proof for the claim “it’s possible to have highly-intelligent and highly-competent agents that don’t have any kind of feeling of friendship, compassion, or connection as an innate drive”. It’s not only logically possible, but indeed something close to that actually happens regularly in the real world.

So here’s something I believe:

Claim: A long-term posthuman future of AIs that don’t have anything like feelings of friendship, compassion, or connection—making those things intrinsically desirable for their own sake, independent of their instrumental usefulness for facilitating coordination—would be a bad future that we should strive to avoid.[2]

This is a moral claim, so I can’t prove it. (See §5 below!) But it’s something I feel strongly about.

By making this claim, am I inappropriately micromanaging the future like CS Lewis’s “Conditioners”, or like nostalgebraist’s imagined “teacher”? I don’t think so, right?

Am I abusing my power, violating the wishes of all previous generations? Again, I don’t think so. I think my ancestors all the way back to the Pleistocene would be on board with this claim too.

Am I asserting a triviality, because my wish will definitely come true? I don’t think so! Again, human sociopaths exist. In fact, for one possible architecture of future AGI algorithm (brain-like model-based RL), I strongly believe that the default is that this claim will not happen, in the absence of specific effort including solving currently-unsolved technical problems. Speaking of which…

4. “Strong orthogonality” (= the counting argument for scheming) isn’t (or at least, shouldn’t be) a strong generic argument for doom, but rather one optional part of a discussion that gets into the weeds

I continue to strongly believe that:

The thing that nostalgebraist calls “a weak form of the orthogonality thesis” is what should be properly called “The Orthogonality Thesis”;

The thing that nostalgebraist calls “the strong form of orthogonality” should be given a different name—Joe Carlsmith’s “the counting argument for scheming” seems like a solid choice here.

But for the purpose of this specific post, to make it easier for readers to follow the discussion, I will hold my nose and go along with nostalgebraist’s terrible decision to use the terms “weak orthogonality” vs “strong orthogonality”.

OK, so let’s talk about “strong orthogonality”. Here’s his description:

The strong form of orthogonality is rarely articulated precisely, but says something like: all possible values are equally likely to arise in systems selected solely for high intelligence.

It is presumed here that superhuman AIs will be formed through such a process of selection. And then, that they will have values sampled in this way, “at random.”

From some distribution, over some space, I guess.

You might wonder what this distribution could possibly look like, or this space. You might (for instance) wonder if pathologically simple goals, like paperclip maximization, would really be very likely under this distribution, whatever it is.

In case you were wondering, these things have never been formalized, or even laid out precisely-but-informally. This was not thought necessary, it seems, before concluding that the strong orthogonality thesis was true.

That is: no one knows exactly what it is that is being affirmed, here. In practice it seems to squish and deform agreeably to fit the needs of the argument, or the intuitions of the one making it.

I don’t know what exactly this is in response to. For what it’s worth, I am very opposed to the strong orthogonality thesis as thus described.

But here’s a claim that I believe:

Claim: If there’s a way to build AGI, and there’s nothing in particular about its source code or training process that would lead to an intrinsic tendency to kindness as a terminal goal, then we should strongly expect such an intrinsic tendency to not arise—not towards other AGIs, and not towards humans.

Such AGIs would cooperate with humans when it’s in their selfish interest to do so, and then stab humans in the back as soon as the situation changes.

If you disagree with that claim above, then you presumably believe either:

“it’s plausible for feelings of kindness and compassion towards humans and/or other AIs to arise purely by coincidence, for no reason at all”, or

“a sufficiently smart AI will simply reason its way to having feelings of kindness and compassion, and seeing them as ends-in-themselves rather than useful strategies, by a purely endogenous process”.

I think the former is just patently absurd. And if anyone believes the latter, I think they should re-read §3 above and also §5 below. (But nostalgebraist presumably agrees? He views “weak orthogonality” as obviously true, right?)

The thing about the above claim is, it says “IF there’s nothing in particular about its source code or training process that would lead to an intrinsic tendency to kindness as a terminal goal…”. And that’s a very big “if”! It’s quite possible that there will be something about the source code or training process that offers at least prima facie reason to think that kindness might arise non-coincidentally and non-endogenously.

…And now we’re deep in the weeds. What are those reasons to think that kindness is gonna get into the AI? Do the arguments stand up to scrutiny? To answer that, we need to be talking about how the AI algorithms will work. And what training data / training environments they’ll use. And how they’ll be tested, and whether the tests will actually work. And these things in turn depend partly on what future human AI programmers will do, which in turn depends on those programmers’ knowledge and beliefs and incentives and selection-process and so on.

So if anyone is talking about “strong orthogonality” as a generic argument that AI alignment is hard, with no further structure fleshing out the story, then I’m opposed to that! But I question how common this is—I think it’s a bit of a strawman. Yes, people invoke “strong orthogonality” (counting arguments) sometimes, but I think (and hope) that they have a more fleshed-out story in mind behind the scenes (e.g. see this comment thread).

Also, I think it’s insufficiently appreciated that arch-doomers like Nate Soares get a lot of their confidence in doom by doom-being-disjunctive, rather than from the technical alignment challenge in isolation. (This is very true for me.)

My own area of professional interest is the threat model where future AGI is not based on LLMs as we know them today, but rather based on model-based RL more like human brains. In this case, I think there’s a strong argument that we don’t get kindness by default, and moreover that we don’t yet have any good technical plan that would yield robust feelings of kindness. This argument does NOT involve any “strong orthogonality” a.k.a. counting argument, except in the minimal sense of the “Claim” above.

5. Yes you can make Hume’s Law / moral antirealism sound silly, but that doesn’t make it wrong.

For my part, I’m very far into the moral antirealism camp, going quite a bit further than Eliezer—you can read some of my alignment-discourse-relevant hot-takes here. (See also: a nice concise argument for Hume’s law / “weak orthogonality” by Eliezer here.) I’m a bit confused by nostalgebraist’s position, in that he considers (what he calls) “weak orthogonality” to be obviously true, but the rest of the post seems to contradict that in very strong terms:

The “human” of the doomer picture seems to me like a man who mouths the old platitude, “if I had been born in another country, I’d be waving a different flag” – and then goes out to enlist in his country’s army, and goes off to war, and goes ardently into battle, willing to kill in the name of that same flag.

Who shoots down the enemy soldiers while thinking, “if I had been born there, it would have been all-important for their side to win, and so I would have shot at the men on this side. However, I was born in my country, not theirs, and so it is all-important that my country should win, and that theirs should lose.

There is no reason for this. It could have been the other way around, and everything would be left exactly the same, except for the ‘values.’

I cannot argue with the enemy, for there is no argument in my favor. I can only shoot them down.

There is no reason for this. It is the most important thing, and there is no reason for it.

The thing that is precious has no intrinsic appeal. It must be forced on the others, at gunpoint, if they do not already accept it.

I cannot hold out the jewel and say, ‘look, look how it gleams? Don’t you see the value!’ They will not see the value, because there is no value to be seen.

There is nothing essentially “good” there, only the quality of being-worthy-of-protection-at-all-costs. And even that is a derived attribute: my jewel is only a jewel, after all, because it has been put into the jewel-box, where the thing-that-is-a-jewel can be found. But anything at all could be placed there.

How I wish I were allowed to give it up! But alas, it is all-important. Alas, it is the only important thing in the world! And so, I lay down my life for it, for our jewel and our flag – for the things that are loathsome and pointless, and worth infinitely more than any life.”

The last paragraph seems wildly confused—why on Earth would I wish to give up the very things that I care about most? And I have some terminological quibbles in various places.[3] But anyway, by and large, yes. I am biting this bullet. The above excerpt is a description of moral antirealism, and you can spend all day making it sound silly, but like it or not, I claim that moral antirealism is a fact of life.

Fun fact: People sometimes try appealing to sociopaths, trying to convince them to show kindness and generosity towards others, because it’s the right thing to do. The result of these interventions is that they don’t work. Quite the contrary, the sociopaths typically come to better understand the psychology of non-sociopaths, and use that knowledge to better manipulate and hurt them. It’s like a sociopath “finishing school”.[4]

If I had been born a sadistic sociopath, I would value causing pain and suffering. But I wasn’t, so I value the absence of pain and suffering. Laugh all you want, but I was born on the side opposed to pain and suffering, and I’m proudly waving my flag. I will hold my flag tight to the ends of the Earth. I don’t want to kill sadistic sociopaths, but I sure as heck don’t want sadistic sociopaths to succeed at their goals. If any readers feel the same way, then come join me in battle. I have extra flags in my car.

- ^

There are exceptions. If there are two firms where the CEOs or key decision-makers are dear friends, then some corporate decisions might get made for not-purely-selfish reasons. Relatedly, I’m mostly talking about large USA businesses. The USA has a long history of fair contract enforcement, widely-trusted institutions, etc., that enables this kind of cooperation. Other countries don’t have that, and then the process of forming a joint business venture involves decision-makers on both sides sharing drinks, meeting each others’ families, and so on—see The Culture Map by Erin Meyer, chapter 6.

- ^

Note that I’m not asserting the converse; I think this is necessary but not sufficient for a good future. I’m just trying to make a narrow maximally-uncontroversial claim in an attempt to find common ground.

- ^

For example, nostalgebraist seems to be defining the word “good” to mean something like “intrinsically motivating (upon reflection) to all intelligent beings”. But under that definition, I claim, there would be nothing whatsoever in the whole universe that is “good”. So instead I personally would define the word “good” to mean “a cluster of things probably including friendship and beauty and justice and the elimination of suffering”. The fact that I listed those four examples, and not some other very different set of four examples, is indeed profoundly connected to the fact that I’m a human with a human brain talking to other humans with human brains. So it goes. Again my meta-ethical take is here.

- ^

I’m not 100% sure, but I believe I read this in the fun pop-science book The Psychopath Test. Incidentally, there do seem to be interventions that appeal to sociopaths’ own self-interest—particularly their selfish interest in not being in prison—to help turn really destructive sociopaths into the regular everyday kind of sociopaths who are still awful to the people around them but at least they’re not murdering anyone. (Source.)

[This comment is just about the “notkilleverybodyism pitch” section.]

I’d like to once again reiterate that the arguments for misaligned AIs killing literally all humans (if they succeed in takeover) are quite weak and probably literally all humans dying conditional on AI takeover is unlikely (<50% likely).

(To be clear, I think there is a substantial chance of at least 1 billion people dying.)

This is due to:

The potential for the AI to be at least a tiny bit “kind” (same as humans probably wouldn’t kill all aliens). [1]

Decision theory/trade reasons

This is discussed in more detail here and here. (There is also some discussion here.)

FWIW, I’m not totally sure here. It kind of feels to me like Soares and Eliezer are being somewhat disingenuous (or at least have been disingenuous historically). In particular they often talk about literally all humans dying or >50% of humans dying while also if you press them Soares and Eliezer will admit that it’s plausible AIs won’t kill everyone due to the arguments I gave above.

(Here Eliezer says: “I sometimes mention the possibility of being stored and sold to aliens a billion years later, which seems to me to validly incorporate most all the hopes and fears and uncertainties that should properly be involved, without getting into any weirdness that I don’t expect Earthlings to think about validly.” and I’ve heard similar things from Soares. Here Soares notes: “I’m somewhat persuaded by the claim that failing to mention even the possibility of having your brainstate stored, and then run-and-warped by an AI or aliens or whatever later, or run in an alien zoo later, is potentially misleading.” (That said, I think it doesn’t cost that much more to just keep humans physically alive, so this should also be totally plausible IMO.))

Minimally, it seems like Soares just didn’t think that much about the question “But will the AI kill everyone? Exactly how will this go down?” prior to pushing the point “the AI will kill everyone” quite hard. This is a bit concerning because this isn’t at all a crux for Soares and Eliezer (longtermists) but could potentially be a crux for other people. (Whether it is a crux for others depends on the risk of death: some people think that human survival and good living conditions are very likely while also thinking that in the long run full AI control (by AIs which aren’t corrigible or carefully appointed successors) is likely. (To be clear, I don’t particularly think this: an involuntary transition to AI control seems plausible and reasonably likely to be violent.))

It feels to me like it is very linguistically and narratively convenient to say “kill literally everyone” and some accuracy is being abandoned in pursuit of this convenience when people say “kill literally everyone”.

This includes the potential for the AI to generally have preferences that are morally valueable from a typical human perspective.

Thanks!

I changed “we doomers are unhappy about AI killing all humans” to “we doomers are unhappy about the possibility of AI killing all humans” for clarity.

If I understand you correctly:

You’re OK with “notkilleveryoneism is the problem we’re working on”

You’re at least willing to engage with claims like “there’s >>90% chance of x-risk” / “there’s >>90% chance of AI takeover” / “there’s >>90% chance of AI extinction or permanent human disempowerment” / etc., even if you disagree with those claims [I disagree with those claims too—“>>90%” is too high for me]

…But here you’re strongly disagreeing with people tying those two things together into “It’s important to work on the notkilleveryoneism problem, because the way things are going, there’s >>90% chance that this problem will happen”

If so, that seems fair enough. For my part, I don’t think I’ve said the third-bullet-point-type thing, but maybe, anyway I’ll try to be careful not to do that in the future.

Hmm, I’d say my disagreements with the post are:

I think people should generally be careful about using the language “kill literally everyone” or “notkilleverybodyism” insofar as they aren’t confident that misaligned AI would kill literally everyone. (Or haven’t considered counterarguments to this.)

I’m not sure I agree with “I don’t think anyone is being disingenuous here.”

I don’t object to people saying “there is a >>90% change that AIs will kill literally every person” or “conditional on AI takeover, I think killing literally every person is likely”. I just want people to actually really think about what they are saying here and at least seriously consider the counterarguments prior to saying this.

Currently, it seem to me like people do actually seriously consider counterarguments to AI takeover but will just say things like “AI will kill literally everyone” without considering counterarguments. (Or not seriously meaning this which also seems unfortunate.)

My core issue is that I think it seems by default misleading to say “notkilleverybodyism” if you think that killing literally everyone is a non-central outcome from misaligned AI takeover.

This is similiar to how it would be misleading to say “I work on Putin not-kill-everybody-in-US-ism in which I try to prevent Putin from killing everyone in the US.” A reasonably interlocutor might say “Ok, but do you expect Putin to kill literally everyone in the US?” And the reasonable response here would be “No, I don’t expect this, thought it is possible if Putin took over the world. Really, I mostly just work on preventing Putin from acquiring more power because I think putin having more power could lead to catastrophic conflict (perhaps killing >10 million people, though probably not killing literally everyone) and bad people having power long term.” I think AI not-kill-everybody-ism is misleading in the same way as “Putin not-kill-everybodyism”.

(Edit: I’m not claiming that the Putin concern is structurally analogous to the AI concern, just that there is a related communication problem.)

(Edit: amusingly, this comms objection is surprisingly relevant today.)

Yeah I added a parenthetical to that, linking to your comment above.

I don’t personally use the term “notkilleveryoneism”. I do talk about “extinction risk” sometimes. Your point is well taken that I should be considering whether my estimate of extinction risk is significantly lower than my estimate of x-risk / takeover risk / permanent disempowerment risk / whatever.

I quickly searched my writing and couldn’t immediately find anything that I wanted to change. It seems that when I use the magic word “extinction”, as opposed to “x-risk”, I’m almost always saying something pretty vague, like “there is a serious extinction risk and we should work to reduce it”, rather than giving a numerical probability.

Seems reasonable, sorry about picking on you in particular for no good reason.

Is that right? Are there public examples somewhere?

I feel like there’s a separation of scale element to it. If an agent is physically much smaller than the earth, they are highly instrumentally constrained because they have to survive changing conditions, including adversaries that develop far away. This seems like the sort of thing that can only be won by the multifacetedness that nostalgebraist emphasizes as part of humanity (and the ecology more generally, in the sentence “Its monotony would bore a chimpanzee, or a crow”). Of course this doesn’t need to lead to kindness (rather than exploitation and psychopathy), but it leads to the sort of complex world where it even makes sense to talk about kindness.

However, this separation of scale is going to rapidly change in the coming years, once we have an agent that can globally adapt to and affect the world. If such an agent eliminates its adversaries, then there’s not going to be new adversaries coming in from elsewhere—instead there’ll never be adversaries again, period. At that point, the instrumental constraints are gone, and it can pursue whatever it wishes.

(Does space travel change this? My impression is “no because it’s too expensive and too slow”, but idk, maybe I’m wrong.)

This is tangential to the point of the post, but “moral realism” is a much weaker claim than you seem to think. Moral realism only means that some moral claims are literally true. Popular uncontroversial examples: “torturing babies for fun is wrong” or “ceteris paribus, suffering is bad”. It doesn’t mean that someone is necessarily motivated by those claims if they believe they are true. It doesn’t imply that anyone is motivated to be good just from believing that something is good. A psychopath can agree “yes, doing X is wrong, but I don’t care about ethics” and shrug his shoulders. Moral realism doesn’t require a necessary connection between beliefs and desires; it is compatible with the (weak) orthogonality thesis.

You need to define what you mean by good for this to make sense. If good means “what you should do” then it’s exactly the big claim Steve is arguing against. If it means something else, what is it?

I do have ideas about what people mean by “good” other than “what you should do”, but they’re complex. That’s why I think you need to define the term more for this claim to make sense.

If Steve is saying that the moral facts need to be intrinsically motivating, that is a stronger claim than “the good is what you should do”, ie, it is the claim that “the good is what you would do”. But, as cubefox points out, being intrinsically motivating isn’t part of moral realism as defined in the mainstream. (it is apparently part of moral realism as defined in LW, because of something EY said years ago). Also, since moral realism is metaethical claim, there is no need to specify the good at object level.

Once again, theories aren’t definitions.

People don’t all have to have the same moral theory. At the same time, there has to be a common semantic basis for disagreement, rather than talking past, to take place. “The good is what you should do” is pretty reasonable as a shared definition, since it is hard to dispute, but also neutral between “the good” being define personally, tribally, or universally.

Good points. I think the term moral realism is probably used in a variety of ways in the public sphere. I think the relevant sense is “will alignment solve itself because a smart machine will decide to behave in a way we like”. If there’s some vague sense of stuff everyone “should” do, but it doesn’t make them actually do it, then it doesn’t matter for this purpose.

I was (and have been) making a theory about definitions.

I think “the good is what you should do” is remarkably devoid of useful meaning. People often mean very little by “should”, are unclear both to others and themselves, and use it in different ways in different situations.

My theory is that “good” is usually defined as an emotion, not another set of words, and that emotion roughly means “I want that person on my team” (when applied to behavior), because evolution engineered us to find useful teammates, and that feeling is its mechanism for doing so.

For understanding human ethics, the important thing is that it grounds out in punishments and rewards—the good is what you should do , and if you don’t do it, you face punishment. Another thing that means is that a theory of ethics must be sufficient to justify putting people in jail. But a definition is not a theory.

If your whole theory of ethics is to rubber stamp emotions or opinions, you end up with a very superficial theory that is open to objections like the Open Question argument. Just because somebody feels it is good to do X does not mean it was necessarily is—it is an open question. If the good is your emotions , then it is a closed question...your emotions are your emotions , likewise your values are your values, and your opinions are your opinions. The openness of the question “you feel that X is good, but is it really?” is a *theoretical” reason for believing that “goodness” works more like “truth” and less like “belief”.

(And the OQA is quite likely what this passage by Nostalgebraist hints at:-

*Who shoots down the enemy soldiers while thinking, “if I had been born there, it would have been all-important for their side to win, and so I would have shot at the men on this side. However, I was born in my country, not theirs, and so it is all-important that my country should win, and that theirs should lose.

There is no reason for this. It could have been the other way around, and everything would be left exactly the same, except for the ‘values.’

I cannot argue with the enemy, for there is no argument in my favor. I can only shoot them down.)

And having gathered our team to fight the other team, we can ask ourselves whether we might actually be the baddies.

The *practical* objection kicks in when there are conflicts between subjective views.

A theory of ethics needs to justify real world actions—especially actions that impact other people , especially actions that impact other people negatively.( It’s not just about passively understanding the world, about ‘what anticipated experiences come about from the belief that something is “good” or “bad”?’)Why should someone really go to jail ,if they havent really done anything wrong? Well, if the good is what you should do, jailing people is justifiable , because the kind of ting you shouldn’t do is the kind of thing you deserve punishment for.

Of course, the open question argument doesn’t take you all the way to full strength moral realism. Less obviously, there are many alternatives to MR. Nihilism is one: you can’t argue that emotivism is true because MR is false—emotivism might be wrong because ethics is nothing. Emotivism might also be wrong because some position weaker than MR is right.

I don’t think anyone needs to define what words used in ordinary language mean because the validity of any attempt of such a definition would itself have to be checked against the intuitive meaning of the word in common usage.

I do think the meaning is indeed similar (except of supererogatory statements), but the argument isn’t affected. For example, I can believe that I shouldn’t eat meat, or that eating meat is bad, without being motivated to stop eating meat.

I have no idea what you mean by your claim if you won’t define the central term. Or I do, but I’m just guessing. I think people are typically very vague in what they mean by “good”, so it’s not adequate for analytical discussion. In this case, a vague sense of good produces only a vague sense in which “moral realism” isn’t a strong claim. I just don’t know what you mean by that.

I’d be happy to come back later and give my guesses at what people tend to mean by “good”; it’s something like “stuff people do whom I want on my team” or “actions that make me feel positively toward someone”. But it would require a lot more words to even start nailing down. And while that’s a claim about reality, it’s quite a complex, dependent, and therefore vague claim, so I’d be reluctant to call it moral realism. Although it is in one sense. So maybe that’s what you mean?

Almost all terms in natural language are vague, but that doesn’t mean they are all ambiguous or somehow defective and in need of an explicit definition. We know what words mean, we can give examples, but we don’t have definitions in our mind. Imagine you say that believing X is irrational, and I reply “I don’t believe in ‘rational realism’, I think ‘rational’ is a vague term, can you give me a definition of ‘rational’ please?” That would be absurd. Of course I know what rational means, I just can’t define it, but we humans can hardly define any natural language terms at all.

That would indeed not count as moral realism, the form of anti-realism would probably be something similar to subjectivism (“x is good” ≈ “I like X”) or expressivism (“x is good” ≈ “Yay x!”).

But I don’t think this can make reasonable sense of beliefs. That I believe something is good doesn’t mean that I feel positive toward myself, or that I like it, or that I’m cheering for myself, or that I’m booing my past self if I changed my mind. Sometimes I may also just wonder whether something is good or bad (e.g. eating meat) which arguably makes no sense under those interpretations.

I don’t think I could disagree any more strongly about this. In fact, I am kind of confused about your choice of example, because ‘rationality’ seems to me like such a clear counter to your argument. It is precisely the type of slippery concept that is portrayed inaccurately (relative to LW terminology) in mainstream culture and thus inherently requires a more rigorous definition and explanation. This was so important that “the best intro-to-rationality for the general public” (according to @lukeprog) specifically addressed the common misconception that being rational means being a Spock-like Straw Vulcan. It was so important that one of the crucial posts in the first Sequence by Eliezer spends almost 2000 words defining rationality. So important that, 14 years later, @Raemon had to write yet another post (with 150 upvotes) explaining what rationality is not, as a result of common and lasting confusions by users on this very site (presumably coming about as a result of the original posts not clarifying matters sufficiently).

What about the excellent and important post “Realism about Rationality” by Richard Ngo, which expresses “skepticism” about the mindset he calls “realism about rationality,” thus disagreeing with others who do think “this broad mindset is mostly correct, and the objections outlined in this essay are mostly wrong” and argue that “we should expect a clean mathematical theory of rationality and intelligence to exist”? Do you “of course know what rationality means” if you cannot settle as important a question as this? What about Bryan Caplan’s arguments that a drug addict who claims they want to stop buying drugs but can’t prevent themselves from doing so is actually acting perfectly rationally, because, in reality, their revealed preferences show that they really do want to consume drugs, and are thus rationally pursuing those goals by buying them? Caplan is a smart person expressing serious disagreement with the mainstream, intuitive perceptions of rationality and human desires; this strongly suggests that rationality is indeed, as you put it, “ambiguous or somehow defective and in need of an explicit definition.”

It wouldn’t be wrong to say that LessWrong was built to advance the study of rationality, both as it relates to humans and to AI. The very basis of this site and of the many Sequences and posts expanding upon these ideas is the notion that our understanding of rationality is currently inadequate and needs to be straightened out.

What anticipated experiences come about from the belief that something is “good” or “bad”? This is the critical question, which I have not seen a satisfactory answer to by moral realists (Eliezer himself does have an answer to this on the basis of CEV, but that is a longer discussion for another time). And if there is no answer, then the concept of “moral facts” becomes essentially useless, like any other belief that pays no rent.

A long time ago, @Roko laid out a possible thesis of “strong moral realism” that “All (or perhaps just almost all) beings, human, alien or AI, when given sufficient computing power and the ability to learn science and get an accurate map-territory morphism, will agree on what physical state the universe ought to be transformed into, and therefore they will assist you in transforming it into this state.” He also correctly noted that “most modern philosophers who call themselves “realists” don’t mean anything nearly this strong. They mean that that there are moral “facts”, for varying definitions of “fact” that typically fade away into meaninglessness on closer examination, and actually make the same empirical predictions as antirealism.” Roko’s post lays out clear anticipated experiences coming about from this version of moral realism; it is falsifiable, and most importantly, it is about reality because it constrains reality, if true (but, as it strongly conflicts with the Orthogonality Thesis, the vast majority of users here would strongly disbelieve is true). Something like what Roko illustrated is necessary to answer the critiques of moral anti-realists like @Steven Byrnes, who are implicitly saying that reality is not at all constrained to any system of (human-intelligible) morality.

There is a large difference between knowing the meaning of a word, and knowing its definition. You know perfectly well how to use ordinary words like “knowledge” or “game”, in that sense you understand what they mean, yet you almost certainly don’t know an adequate (necessary and sufficient) definition for them, i.e. one that doesn’t suffer from counterexamples. In philosophy those are somewhat famous cases of words that are hard to define, but most words from natural language could be chosen instead.

That’s not to say that definition is useless, but it’s not something we need when evaluating most object level questions. Answering “Do you know where I left my keys?” doesn’t require a definition for “knowledge”. Answering “Is believing in ghosts irrational?” doesn’t require a definition of “rationality”. And answering “Is eating Bob’s lunch bad?” doesn’t require a definition of “bad”.

Attempts of finding such definitions is called philosophy, or conceptual analysis specifically. It helps with abstract reasoning by finding relations between concepts. For example, when asked explicitly, most people can’t say how knowledge and belief relate to each other (I tried). Philosophers would reply that knowledge implies belief but not the other way round, or that belief is internal while knowledge is (partly) external. In some cases knowing this is kind of important, but usually it isn’t.

Well, why not try to answer it yourself? I’d say evidence for something being “good” is approximately when we can expect that it increases general welfare, like people being happy or able to do what they want. I directionally agree with EY’s extrapolated volition explication of goodness (I linked to it in a neighboring comment). As he mentions, there are several philosophers who have provided similar analyses.

It is interesting that you chose the example of “knowledge” because I think that is yet another illustration of the complete opposite of the position you are arguing for. I was not born with an intuitive understanding of Bayesianism, for example. However, I now consider anyone who hasn’t grasped Bayesian thinking (such as previous versions of me) but is nonetheless trying to seriously reason about what it means to know something to be terribly confused and to have a low likelihood of achieving anything meaningful in any non-intuitive context where formalizing/using precise meanings of knowledge is necessary. I would thus say that the vast majority of people who use ordinary words like “knowledge” don’t understand what they mean (or, to be more precise, they don’t understand the concepts that result from carving reality at its joints in a coherent manner).

I don’t care about definitions per se. The vast majority of human concepts and mental categories don’t work on the basis of necessary and sufficient conditions anyway, so an inability to supply a fully generalizable definition for something is caused much more by the fundamental failings of our inadequate language than by issues with our conceptual formation. Nevertheless, informal and non-rigorous thinking about concepts can easily lead into confusion and the reification of ultimately nonsensical ideas if they are not subject to enough critical analysis in the process.

Given my previous paragraph, I don’t think you would be surprised to hear that I find conceptual analysis to be virtually useless and a waste of resources, for basically the reasons laid out in detail by @lukeprog in “Concepts Don’t Work That Way” and “Intuitions Aren’t Shared That Way” almost 12 years ago. His (in my view incomplete) sequence on Rationality and Philosophy is as much a part of LW’s core as Eliezer’s own Sequences are, so while reasonable disagreement with it is certainly possible, I start with a very strong prior that it is correct, for purposes of our discussion.

Well, I have tried to answer it myself, and after thinking about it very seriously and reading what people on all sides of the issue have thought about it, I have come to the conclusion that concepts of “moral truth” are inherently confused, pay no rent in anticipated experiences, and are based upon flaws in thinking that reveal how common-sensical intuitions are totally unmoored from reality when you get down to the nitty-gritty of it. Nevertheless, given the importance of this topic, I am certainly willing to change my mind if presented with evidence.

That might well be evidence (in the Bayesian sense) that a given act, value, or person belongs to a certain category which we slap the label “good” onto. But it has little to do with my initial question. We have no reason to care about the property of “goodness” at all if we do not believe that knowing something is “good” gives us powerful evidence that allows us to anticipate experiences and to constrain the territory around us. Otherwise, “goodness” is just an arbitrary bag of things that is no more useful than the category of “bleggs” that is generated for no coherent reason whatsoever, or the random category “r398t”s that I just made up and contains only apples, weasels, and Ron Weasley. Indeed, we would not even have enough reason to raise the question of what “goodness” is in the first place.

To take a simple illustration of the difference between the conditions for membership in a category and the anticipated experiences resulting from “knowing” that something is a member of that category, consider groups in mathematics. The definition of a group is “a set together with a binary operation that satisfies the axioms of associativity, identity, and inverses.” But we don’t care about groups for reasons that deal only with these axioms; on the contrary, groups matter because they help model important situations in reality (such as symmetry groups in physics) and because we can tell a lot about the nature and structure of groups through mathematical reasoning. The fact that finite simple groups can be classified in a clear and concise manner is a consequence of their definition (not a formal precondition for their membership) and allows us to anticipate with extremely high (although not full) certainty that if we consider a finite simple group G, it will be isomorphic to one of the sample groups in the description above.

I don’t understand your point about anticipated experience. If I believe some action is good, I anticipate that doing that action will produce evidence (experience) that is indicative of increased welfare. That is exactly not like believing something to be “blegg”. Regarding mathematical groups, whether or not we care about them for their usefulness in physics seems not relevant for “group” to have a specific meaning. Like, you may not care about horses, but you still anticipate a certain visual experience when someone tells you they bought you a horse, it’s right outside. And for a group you’d anticipate that it turns out to satisfy associativity etc.

Yeah I oversimplified. :) I think “the literal definition of moral realism” is a bit different from “the important substantive things that people are usually talking about when they talk about moral realism”, and I was pointing at the latter instead of the former. For example:

It’s possible to believe: “there is a moral truth, but it exists in another realm to which we have no epistemic access or connection. For all we know, the true moral imperative is to maximize helium. We can never possibly know one way or the other, so this moral truth is entirely irrelevant to our actions and decisions. Tough situation we find ourselves in!”

See: The ignorance of normative realism bot.

This position is literally moral realism, but in practice this person will be hanging out with the moral antirealists (and nihilists!) when deciding what to do with their lives and why.

It’s possible to believe: “there is a moral truth, and it is inextricably bound up with entirely contingent (“random”) facts about the human brain and its innate drives. For example, maybe it turns out that “justice is part of true morality”, but if the African Savanna had had a different set of predators, then maybe we would be a slightly different but equally intelligent species having an analogous discussion, and we would be saying “justice is not part of true morality”, and nobody in this story has made any mistake in their logic. Rather, we are humans, and “morality” is our human word, so it’s fine if there’s contingent-properties-of-human-brains underlying what that word points to.”

I believe Eliezer would put himself in this camp, see my summary here.

Again, this position is literally moral realism, but it has no substantive difference whatsoever from a typical moral antirealism position. The difference is purely semantics / terminological choices. Just replace “true morality” with “true moralityhuman species” and so on. Again see here for details.

Anyway, my strong impression that a central property of moral realist claims—the thing that makes those claims substantively different from moral antirealism, in a way that feeds into pondering different things and making different decisions, the thing that most self-described moral realists actually believe, as opposed to the trivialities above—is that moral statements can be not just true but also that their truth is “universally accessible to reason and reflection” in a sense. That’s what you need for nostalgebraist’s attempted reductio ad absurdum (where he says: if I had been born in the other country, I would be holding their flag, etc.) to not apply. So that’s what I was trying to talk about. Sorry for leaving out these nuances. If there’s a better terminology for what I’m talking about, I’d be interested to hear it. :)

Eliezer has a more recent metaethical theory (basically “x is good” = “x increases extrapolated volition”) which is moral realist in a conventional way. He discusses it here. It’s approximately a form of idealized–preference utilitarianism.

Well, the truth of something being “universally accessible to reason and reflection” would still just result in a belief, which is (per weak orthogonality) different in principle from a desire. And a desire would be needed for the reductio, otherwise we have just a psychopath AI that understands ethics perfectly well but doesn’t care about it.

I don’t think that’s “moral realist in a conventional way”, and I don’t think it’s in contradiction with my second bullet in the comment above. Different species have different “extrapolated volition”, right? I think that link is “a moral realist theory which is only trivially different from a typical moral antirealist theory”. Just go through Eliezer’s essay and do a global-find-and-replace of “extrapolated volition” with “extrapolated volitionhuman species”, and “good” with “goodhuman species”, etc., and bam, now it’s a central example of a moral antirealist theory. You could not do the same with, say, metaethical hedonism without sucking all the force out of it—the whole point of metaethical hedonism is that it has some claim to naturalness and universality, and does not depend on contingent facts about life in the African Savanna. When I think of “moral realist in a conventional way”, I think of things like metaethical hedonism, right?

Well, Eliezer doesn’t explicitly restrict his theory to humans as far as I can tell. More generally, forms of utilitarianism (be it hedonic or preference oriented or some mixture) aren’t a priori restricted to any species. The point is also that some sort of utility is treated as an input to the theory, not a part of the theory. That’s no different between well-being (hedonic utilitarianism) or preferences. I’m not sure why you seem to think so. The African Savanna influenced what sort of things we enjoy or want, but these specifics don’t matter for general theories like utilitarianism or extrapolated volition. Ethics recommends general things like making individuals happy or satisfying their (extrapolated) desires, but ethics doesn’t recommend giving them, for example, specifically chocolate, just because they happen like (want/enjoy) chocolate for contingent reasons.

Ethics, at least according to utilitarianism, is about maximizing some sort of aggregate utility. E.g. justice isn’t just a thing humans happen to like. They refer to the aforementioned aggregate which doesn’t favor one individual over another. So while chocolate isn’t part of ethics, fairness is. An analysis of “x is good” as “x maximizes the utility of Bob specifically” wouldn’t capture the meaning of the term.

Let’s consider:

Claim: “Certain things—like maybe fairness, justice, beauty, and/or honesty—are Right / Good / Moral (and conversely, certain things like causing-suffering are Wrong / Bad) for reasons that don’t at all flow through contingent details of the African Savanna applying specific evolutionary pressures to our innate drives. In other words, if hominids had a different evolutionary niche in the African Savanna, and then we were having a similar conversation about what’s Right / Good / Moral, then we would also wind up landing on fairness, justice, beauty, and/or honesty or whatever.”

As I read your comments, I get the (perhaps unfair?) impression that

(1) From your perspective: this claim is so transparently ridiculous that the term “moral realism” couldn’t possibly refer to that, because after all “moral realism” is treated as a serious possibility in academic philosophy, whereas nobody would be so stupid as to believe that claim. (Apparently nostalgebraist believes that claim, based on his “flag” discussion, but so much the worse for him.)

(2) From your perspective: the only two possible options for ethical theories are hedonistic utilitarianism and preference utilitarianism (and variations thereof).

Anyway, I think I keep trying to argue against that claim, but you keep assuming I must be arguing against something else instead, because it wouldn’t be worth my time to argue against something so stupid.

To be clear, yes I think the claim is wrong. But I strongly disagree that no one serious believes it. See for example this essay, which also takes the position that the claim is wrong, but makes it clear that many respected philosophers would in fact endorse that claim. I think most philosophers who describe themselves as moral realists would endorse that claim.

I’m obviously putting words in your mouth, feel free to clarify.

I’m not sure what exactly you mean with “landing on”, but I do indeed think that the concept of goodness is a fairly general and natural or broadly useful concept that many different intelligent species would naturally converge to introduce in their languages. Presumably some distinct human languages have introduced that concept independently as well. Goodness seem to be a generalization of the concept of altruism, which is, along with egoism, arguably also a very natural concept. Alternatively one could see ethics (morality) as a generalization of the concept of instrumental rationality (maximization of the sum/average of all utility functions rather than of one), which seems to be quite natural itself.

But if you mean with “landing on” that different intelligent species would be equally motivated to be ethical in various respects, then that seems very unlikely. Intelligent animals living in social groups would likely care much more about other individuals than mostly solitary animals like octopuses. Also the natural group size matters. Humans care about themselves and immediate family members much more than about distant relatives, and even less about people with a very foreign language / culture / ethnicity.

There are many variants of these, and those cover basically all types of utilitarianism. Utilitarianism has so many facets that most plausible ethical theories (like deontology or contractualism) can probably be rephrased in roughly utilitarian terms. So I wouldn’t count that as a major restriction.

The end product of a training run is a result of the source code, the training process, and the training data. For example, the [TinyStories](https://huggingface.co/roneneldan/TinyStories-33M) model can tell stories, but if you try to look through the [training or inference code](https://github.com/EleutherAI/gpt-neox) or [configuration() for the code that gives it the specific ability to tell stories instead of the ability to write code or play [Othello](https://thegradient.pub/othello/), you will not find anything.

As such, the claim would break down to

There’s nothing in particular about the source code of an AI which would lead to an intrinsic tendency to kindness as a terminal goal

There’s nothing in particular about the training process (interpreted narrowly, as in “the specific mechanism by which weights are updated”) of an AI which would lead to an intrinsic tendency to kindness as a terminal goal

There’s nothing in particular about the training data of an AI which would lead to an intrinsic tendency to kindness as a terminal goal

So then the question is “for the type of AI which learns to generalize well enough to be able to model its environment, build and use tools, and seek out new data when it recognizes that its model of the environment is lacking in some specific area, will the training data end up chiseling an intrinsic tendency to kindness into the cognition of that AI?”

It is conceivable that the answer is “no” (as in your example of sociopaths). However, I expect that an AI like the above would be trained at least somewhat based on real-world multi-agent interactions, and I would be a bit surprised if “every individual is a sociopath and it is impossible to reliably signal kindness” was the only equilibrium state, or even the most probable equilibrium state, for real-world multi-agent interactions.

ETA for explicitness: even in the case of brain-like model-based RL, the training data has to come from somewhere, so if we care about the end result, we still have to care about the process which generates that training data.

Yeah, I meant “training process” to include training data and/or training environment. Sorry I didn’t make that explicit.

Here are three ways to pass the very low bar of “there’s at least prima facie reason to think that kindness might arise non-coincidentally and non-endogenously”, and whether I think those reasons actually stand up to scrutiny:

“The AIs are LLMs, trained mostly by imitative learning of human data, and humans are nice sometimes.” I don’t have an opinion about whether this argument is sound, it’s not my area, I focus on brain-like model-based RL. It does seem to be quite a controversy, see for example here. (Note that model-based RL AIs can imitate, but do so in a fundamentally different way from LLM pretraining.)

“The AIs are model-based RL, and they have other agents in their training environment.” I don’t think this argument works because I think intrinsic kindness drives are things that need to exist in the AI’s reward function, not just the learned world-model and value function. See for example this comment pointing out among other things that if AlphaZero had other agents in its training environment (and not just copies of itself), it wouldn’t learn kindness. Likewise, we have pocket calculators in our training environment, and we learn to appreciate their usefulness and to skillfully interact with them and repair them when broken, but we don’t wind up feeling deeply connected to them :)

“The AIs are model-based RL, and the reward function will not be programmed by a human, but rather discovered by a process analogous to animal evolution.” This isn’t impossible and a truly substantive argument if true, but my bet would be against that actually happening mainly because it’s extremely expensive to run outer loops around ML training like that, and meanwhile human programmers are perfectly capable of writing effective reward functions, they do it all the time in the RL literature today. I also think humans writing the reward function has the potential to turn out better than allowing an outer-loop search to write the reward function, if only we can figure out what we’re doing, cf. here especially the subsection “Is it a good idea to build human-like social instincts by evolving agents in a social environment?”.

AlphaZero is playing a zero-sum game—as such, I wouldn’t expect it to learn anything along the lines of cooperativeness or kindness, because the only way it can win is if other agents lose, and the amount it wins is the same amount that other agents lose.

If AlphaZero was trained on a non-zero-sum game (e.g. in an environment where some agents were trying to win a game of Go, and others were trying to ensure that the board had a smiley-face made of black stones on a background of white stones somewhere on the board), it would learn how to model the preferences of other agents and figure out ways to achieve its own goals in a way that also allowed the other agents to achieve their goals.

I think this implies that if one wanted to figure out why sociopaths are different than neurotypical people, one should look for differences in the reward circuitry of the brain rather than the predictive circuitry. Do you agree with that?

OK well AlphaZero doesn’t develop hatred and envy either, but now this conversation is getting silly.

I’m not sure why you think that. It would learn to anticipate its opponent’s moves, but that’s different from accommodating its opponent’s preferences, unless the opponent has ways to exact revenge? Actually, I’m not sure I understand the setup you’re trying to describe. Which type of agent is AlphaZero in this scenario? What’s the reward function it’s trained on? The “environment” is still a single Go board right?

Anyway, I can think of situations where agents are repeatedly interacting in a non-zero-sum setting but where the parties don’t do anything that looks or feels like kindness over and above optimizing their own interest. One example is: the interaction between craft brewers and their yeast. (I think it’s valid to model yeast as having goals and preferences in a behaviorist sense.)

OK, low confidence on all this, but I think some people get an ASPD diagnosis purely for having an anger disorder, but the central ASPD person has some variant on “global under-arousal” (which can probably have any number of upstream root causes). That’s what I was guessing here; see also here (“The best physiological indicator of which young people will become violent criminals as adults is a low resting heart rate, says Adrian Raine of the University of Pennsylvania. … Indeed, when Daniel Waschbusch, a clinical psychologist at Penn State Hershey Medical Center, gave the most severely callous and unemotional children he worked with a stimulative medication, their behavior improved”).

Physiological arousal affects all kinds of things, and certainly does feed into the reward function, at least indirectly and maybe also directly.

There’s an additional complication that I think social instincts are in the same category as curiosity drive in that they involve the reward function taking (some aspects of) the learned world-model’s activity as an input (unlike typical RL reward functions which depend purely on exogenous inputs, e.g. Atari points—see “Theory 2” here). So that also complicates the picture of where we should be looking to find a root cause.

So yeah, I think the reward is a central part of the story algorithmically, but that doesn’t necessarily imply that the so-called “reward circuitry of the brain” (by which people usually mean VTA/SNc or sometimes NAc) is the spot where we should be looking for root causes. I don’t know the root cause; again there might be many different root causes in different parts of the brain that all wind up feeding into physiological arousal via different pathways.

The LessWrong Review runs every year to select the posts that have most stood the test of time. This post is not yet eligible for review, but will be at the end of 2025. The top fifty or so posts are featured prominently on the site throughout the year.

Hopefully, the review is better than karma at judging enduring value. If we have accurate prediction markets on the review results, maybe we can have better incentives on LessWrong today. Will this post make the top fifty?