A Comprehensive Guide to Running

Just because you can run, it doesn’t mean that you know how to do it properly.

This systematic review showed that:

50% of runners experience an injury each year that prevents them from running for a period of time, and 25% of runners are injured at any given time.

Running-related musculoskeletal injuries (RRMIs) are common among runners. These RRMIs are usually caused by the application of relatively small loads over many repetitive cycles.

When your form is wrong, because running is a repetitive motion, you are compounding the same mistake over and over—a surefire way to get injured. So it’s important to not assume that you know what you’re doing. Running is more complicated than it looks.

I’ve been running for over a decade, and I’ve made almost every mistake possible. I put together this comprehensive guide to help both beginners and experienced runners alike. The sections are presented in descending order of importance (starting with the most important topic: injury prevention).

Once you understand the basics of running, it’s a fun sport/hobby to do by yourself or with friends, the runner’s high feels good, there’s a sense of accomplishment from getting faster, the aerobic exercise gives you energy throughout the day, and you sleep better at night.

Now let’s get started with the most important topic of all.

1. Injury Prevention

(A) Good Running Technique

A physical therapist once told me that good running form is essentially “controlled falling.” You can try the following right now: stand up straight and begin leaning forward while bending at your ankles (like Michael Jackson in the song Smooth Criminal). Keep leaning forward until you’re forced to take a step to stop yourself from falling onto the ground. Did you notice which part of your foot you landed on?

You probably landed on your midfoot (and not on your heels or on your forefoot/toes). (Note: this demo works better when you’re wearing shoes).

(i) Midfoot Striking

Your midfoot is where you want to land with each step while running. Many people run by landing on their heels (known as “heel striking”) too far in front of their bodies (known as “overstriding”)—don’t do this! Experienced runners know that:

Striking the ground on your heel and in front of the body is essentially creating a braking force, sending you backward. When you heel strike, you put excessive stress on your lower legs and knees, increasing the risk of injuries such as shin splints, stress fractures, and runner’s knee.

Landing on your midfoot improves running efficiency, and more importantly, mitigates injury risk compared to heel striking.

So how do you avoid heel striking and learn how to land on the midfoot?

(ii) A 10-16° Forward Lean

To avoid heel striking, lean forward more by bending at the ankles (like Michael Jackson), but do not bend at the waist. A 10-16° angle is optimal for a forward lean. Your head, shoulders, waist, and ankle should be in a straight line.

Running upright, with a 0° forward lean, increases the likelihood of heel striking. And with a forward lean greater than 16°, you might tumble forward onto the ground—ouch. (By the way, Michael Jackson was only able to do a 45° lean because of a clever illusion).

Still unsure on whether you’re heel striking? Try the following. Run upright and really exaggerate a prominent heel strike (by flexing your toes back). Then slowly lean forward at the ankles as you run. As you keep leaning forward more and more, you’ll notice that it’s impossible to land on your heels. Finally, maintain that forward lean and stop tensing your feet. This is what landing on your midfoot should feel like.

(iii) Arms

Pumping your arms harder will not make you faster (unless you’re doing an all-out sprint). Your overall speed comes from your legs, not your arms. The arms are there just to keep you balanced.

Keep your arms bent at a 90° angle, with your fingers curled as if you’re loosely holding an imaginary egg. While you run, your hands should cross your body slightly, but they shouldn’t cross the nipple on the opposite side of your body.

I’ve covered (1) midfoot striking, (2) the forward lean, and (3) arms—the three pillars of good form. Now let’s turn to another aspect of injury prevention: a structured running plan.

(B) Training Structure

Even though you know good running form now, you can still get injured if you don’t understand the basics of a weekly training structure.

(i) Zone Training

You should not perform every run at the same intensity. Instead, you should vary your runs according to different heart rate zones.

These zones can either be (1) calculated based on percentages of your maximum heart rate, or (2) you can estimate them based on vibes.

(1) Calculation:

220 - (your age) = MHR (maximum heart rate, which is measured in beats per minute (BPM)).

So for me that’s 220 − 26 = 194 BPM, which I sometimes achieve when doing an all-out sprint.

The five heart rate zones are then calculated based on a percentage of your maximum heart rate. So for me:

Zone 1 is 50-60% of my MHR, or 94-114 BPM

Zone 2 is 60-70% of my MHR, or 114-134 BPM

Zone 3 is 70-80% of my MHR, or 134-154 BPM

Zone 4 is 80-90% of my MHR, or 154-174 BPM

Zone 5 is 90-100% of my MHR, or 174-194 BPM

GPS watches are great because they can track which heart rate zone you’re running in:

If you plan to train in Zone 2 for the day, periodically look at your watch and adjust your speed. → Heart rate in Zone 3-5? Slow down. Only in Zone 1? Pick up the pace.

After your workout, these watches show the time spent in each zone:

(2) Vibes:

If you don’t want to run with a watch or phone, here’s what the heart rate zones feel like based on vibes:

Zone 1 — Can talk for hours with no problem.

Zone 2 — Can maintain a conversation, but only a few sentences at a time. You’re on the edge between breathing through your nose and having to breathe through your mouth.

Everyone’s Zone 2 is different depending on their cardiovascular fitness.

A new runner may be in Zone 2 while running at a 14 minute/mile pace.

My friend in Chicago who runs 80 miles/week is in Zone 2 while running at a 7 minute/mile pace. His body’s cardiovascular system has become incredibly efficient after years of training. So for him, a 7 minute/mile pace feels like a light jog, but it might feel like an all-out sprint to somebody new to running.

Zone 3 — Can only exchange one sentence at a time. Breathing has become more labored and is now fully through the mouth.

Zone 4 — Can only say a word or two before taking several breaths. This should feel comfortably difficult, but not an all-out sprint.

Colloquially it’s known as a “tempo run” if you stay in Zone 4 for the duration of a run.

Zone 5 — No conversation possible.

This is only achieved during speed workouts or a race.

These training zones are useful if your goal is to get faster (or just not injured). You should use them in combination with the 80⁄20 Principle.

(ii) The 80⁄20 Principle

Imagine going to a gym and attempting your maximum bench press, then coming back the next day to attempt your maximum bench press again, and doing it the next day, and the next…This is stupid. Your body needs time to rest. You will get injured doing this.

The same thing applies to running. Performing every run, day after day, at a high intensity is asking for trouble. And trouble is what I got. The #1 mistake I made for years (which led to many avoidable injuries) was performing all my runs at the same high intensity.

So how do you avoid this and not get injured?

80% of runs should be performed at Zone 2. These easy runs help the body recover from the 20% of runs you perform at Zone 4 or Zone 5.

This is what my running schedule looks like:

Monday — Speed workout on a track, consisting of 400m and 800m reps performed at Zone 4-5, with 3 minutes of rest between reps

Tuesday — Rest day (no run)

Wednesday — Zone 2 run

Thursday — Zone 2 run

Friday — Tempo run (a Zone 4 run)

Saturday — Zone 2 run

Sunday — Zone 2 run

Four of my six runs are at Zone 2—that’s only 66% and not 80%. But take a look at my total time spent running:

My four Zone 2 runs are ~25 minutes each for a total of 100 minutes.

My Zone 4 tempo run is only ~20 minutes.

My Zone 4-5 speed workout is cumulatively ~10 minutes (not counting the time spent resting).

So 100 of my 130 minutes spent running each week is in Zone 2, which is close to 80%. The 80⁄20 Principle for zone training is about the quantity of time, not the number of sessions, spent in each zone.

I stopped getting injured when I started following the 80⁄20 Principle of training, especially once I combined it with the 10% Rule.

(iii) The 10% Rule

If you run your first ever mile today, can you run a marathon tomorrow? No. You’ll probably get injured attempting a marathon. Your body isn’t accustomed to that level of exertion. If you don’t want to get injured, follow the 10% Rule.

The 10% Rule: Only increase the distance or the speed of your runs by at most 10% each week. Don’t increase both in the same week.

Mileage:

Let’s say this is your current running schedule:

Two miles, 4x/week at Zone 2, at a 12 minute/mile pace.

One mile, 1x/week at Zone 4-5, at an 8 minute/mile pace.

Your total mileage is 9 miles/week. Increasing to 10 miles is roughly a 10% increase. Per the 10% Rule, if you increase your mileage in a week, do not also increase your speed that week.

Note: if you’re running 3x/week and want to start running 4x/week, make sure your total mileage for the week doesn’t jump more than 10%.

Speed:

Using the same setup as before:

Two miles, 4x/week at Zone 2, at a 12 minute/mile pace.

One mile, 1x/week at Zone 4-5, at an 8 minute/mile pace.

Instead of increasing your mileage, you could focus on getting faster. For example, try performing your Zone 2 runs at an 11:45 minute/mile pace. If that pace is too fast and pushes you out of Zone 2 and just barely into Zone 3, that’s okay. Do that faster pace for a week, and as your cardiovascular health improves, that new pace will become Zone 2 for you.

Alternatively, you could focus on increasing the pace of your Zone 4-5 run for a particular week.

By following the 10% Rule, you gradually build your muscles and endurance without overwhelming your body with too much running.

(iv) Where to Start if You’re a Beginner

The 10% Rule is meant to prevent you from doing too much. But how much running should you start with per week if you’re a beginner?

I haven’t found a good answer on the internet. Most sources say you’ll be fine if you start by running 10-20 minutes, 3x/week.

I would suggest trying to find your Zone 2 pace and your Zone 4 pace, then start building a training plan (using the 80⁄20 Principle and the 10% Rule) based on your current level of fitness.

(C) Change Shoes Every 250-350 miles

Let’s assume you’ve been running pain-free for the last six months. Your form is good, you follow the 80⁄20 Principle, and adhere to the 10% Rule. But suddenly, you’re starting to experience consistent knee pain, or shin splints, or some other pain on your runs. This could indicate that your shoes are worn out.

Modern running shoes only last 250-350 miles. After that, their tread gets worn out and they lose their cushioning.

See this article: 6 Signs It’s Time to Replace Your Running Shoes

Don’t feel like tracking your accumulated mileage by hand? Consider using the Strava app. It can track the number of miles you’ve used a pair of shoes for, and send you an alert once you’ve reached 250-350 miles. Once you have, throw them out and buy new shoes.

For all other aches and pains…

(D) Hire a Coach or Visit a Physical Therapist

They’re experts. They’re effective. And they’re inexpensive—about $50-100/session.

In my experience, visiting an expert has an extremely high ROI. They can help finetune any running form problems, or provide rehab exercises to help you recover from an injury.

(i) What to Do if You’re Injured

After a decade of running, I tacitly know the difference between discomfort from normal exertion, versus pain that could be indicative of an injury. For beginners, that can be difficult to recognize. So what’s a good benchmark to use?

If your pain is more than a 5 on a scale of 1-10, stop running for the day. If the pain persists for multiple days in a row—you’re probably injured.

Follow the saying: when in doubt, get it checked out. A running professional can diagnose you and provide rehab. Or you can just wait a few days, or weeks, to see if it gets better on its own.

Note: any aches or pains felt for the first half mile of running can sometimes resolve themselves if you just keep going as your body warms up. But after a half mile, if something still doesn’t feel good, stop for the day. Your body has likely not fully recovered from previous runs.

For the love of god, just don’t push through the pain thinking you’re a badass. You’ll just fuck yourself up even more. If you’re in pain, stop running.

If you’re injured and still want to do cardio, consider cross-training. Other sports like cycling, swimming, elliptical, etc., can also be performed with 80⁄20 Zone training to improve your cardio. Just make sure they don’t exacerbate the pain in any way.

(E) Runner’s Stitch

While running, if you’ve ever felt a sharp pain in your abdomen (under your ribs on the left or right side), this is not an injury. This is called a runner’s stitch.

In my experience, runner’s stitches happen when I’m not adequately prepared in terms of my nutrition or hydration (the topics I’ll cover in the next section).

If you’re experiencing a runner’s stitch during a run, there is a remedy:

Let’s say the stitch is on your right side. Breathe in through your nose while landing on your right foot, and breathe out hard through your mouth and stomp on your left foot while continuing to run. Heads-up: this is going to suck. But after 30-60 seconds the stitch should go away. Then you can resume running normally.

Yes, it is possible (but rare) to have a runner’s stitch on both sides. The same remedy applies—you’ll just have to do one side for 30-60 seconds until it’s resolved, and then the other side.

Again, with proper nutrition and hydration, you probably won’t experience this pain during your runs.

2. Nutrition/Hydration

Avoid eating 1 hour within a run. Doing so increases the likelihood of an upset stomach or a runner’s stitch. If you run first thing in the morning, fasted cardio is 100% okay to do—that’s how I do most of my runs.

Avoid drinking lots of water right before a run for the same reason.

I normally wake up, drink a little water, go for a run, and then eat breakfast.

(A) Nutrition

Simple rule: eat like shit, gonna run like shit.

A few months ago, I binged on pizza and beer at a party on a Saturday night. The next morning I went for a run and almost shit my pants.

Try to eat mostly whole foods (as opposed to processed/junk food). I’ve eaten the same breakfast/lunch/dinner every day for 3 years (which I wrote about here). It works for me.

(B) Hydration

You’ll know if you’re hydrated depending on the color of your pee.

Dehydration can lead to worse performance and sometimes a runner’s stitch. Overhydration is also unpleasant (because there’s an uncomfortable pressure of needing to pee).

(i) Are Electrolytes Necessary?

Electrolytes are minerals that restore your energy levels. They can be obtained via beverages (like Gatorade or LMNT), or through a healthy diet.

Are sports drinks with electrolytes mandatory? No. I just eat my normal meals after a run and feel fine.

It’s only at the elite levels of running, or marathons, when you need to start meticulously tracking your energy levels.

3. Should I Warm-Up?

The purpose of warming up is to decrease stiffness and increase performance. Warming up consists of slowly running a short distance of 0.25-0.5 miles (typically done at Zone 1-2), and then doing some dynamic stretches.

Is warming-up always necessary? Eh, usually not. For the bulk of your runs performed at Zone 2, you don’t need to warm-up. The only time I warm-up is before speed workouts and races.

After running a slow half mile, here are my warm-up exercises (which altogether only take ~5 minutes to do):

Hip openers (done forwards and backwards)

4. Gear

Don’t spend too much. Running is an inexpensive sport/hobby.

(A) Shoes

There are two basic types of shoes, each cost ~$100:

Trainers—higher in cushion and protect your legs from the high impact of running. They’re the shoe of choice for all of your Zone 2 training.

Racing flats—more lightweight than trainers because they have less cushioning. They’re your shoe of choice for speed workouts, tempo runs, and races.

Racing flats are not required. For my first 9 years of running, I only used trainers (this brand, specifically). It’s only this past year that I bought my first pair of racing flats. Why? Because I’m getting a lot faster—a few less ounces of weight in my shoes makes a difference in performance for me.

As previously mentioned, I use the Strava app to tell me when I’ve run 250-350 miles in a pair of shoes. Then I replace them.

(B) Clothes

Athletic socks

Athletic shorts/pants

How long should your shorts be? (← sarcastic replies😉)

For shirts and underwear:

Cotton is fine, but it absorbs sweat and can make you feel heavier

“Wick-away” polyester/nylon materials absorb less sweat

Hat and sunglasses are good

For speed workouts and races, I recommend removing your hat because:

“Wearing [a hat] during a race can actually increase your body temperature slightly, which could, in turn, elevate your heart rate. According to a 2019 military study, wearing a hat during exercise can increase your body temperature by up to four per cent.”

(C) GPS Watch

Virtually everyone in my run club uses GPS running watches. They can show your mile pace, what heart rate zone you’re in, and log your runs.

I bought my first GPS watch—a Garmin 245—two years ago. It’s lightweight and more convenient than holding my phone. A little expensive at $200, but a game changer in terms of performance and data tracking.

I’m biased towards the watch because it’s awesome, but I also did my first 8 years of running with just my phone. If you get serious about running, consider buying a GPS running watch.

5. How to Get Faster

If you just want to putter along at Zone 2 or Zone 3 a few times per week and don’t care about getting faster, have fun!

If you want to get faster (and keep increasing your cardiovascular health in the process), here’s how:

One speed workout per week

One tempo run per week

Lose weight

Lift weights at a gym

Note that temperature affects your performance

If you choose to do only one of these, do a speed workout.

(A) Speed Workout

To increase your maximum speed, 1x/week do a speed workout. This can be performed at a high school or college track, or a park, or anywhere where your path is not obstructed.

A speed workout is performed by repeating short intervals at a challenging, fast pace (often at or above your 5K race pace).

A simple version could be to run 400m at Zone 4-5. Do that for 4 to 8 reps total, taking 3 minutes to rest in between reps.

Note: after finishing a speed workout, do not sit down or bend over. You’ll probably cramp up. Instead, keep walking around for a few minutes.

Do a speed workout 1x/week, and the rest of your runs at Zone 2. You’ll start getting faster.

If you want to get even faster, read on.

(B) Tempo Run

To increase your endurance, include a tempo run 1x/week. This should be in addition to your speed workout, not as a replacement, because the speed workouts will yield the most improvements.

The tempo run is a sustained run at Zone 4 (about 20-30 seconds slower per mile than your 5K race pace). It should feel challenging, but it shouldn’t dip into Zone 5.

(i) What’s the Difference Between Speed Workouts and Tempo Runs?

Speed workouts help you get faster by strengthening your leg muscles, therefore increasing your top-end speed.

During intense exercise, lactic acid builds up in your muscles and causes fatigue. Tempo runs increase your endurance by improving your body’s ability to clear lactic acid, therefore delaying fatigue and helping you run faster for longer.

(C) Lose Weight

From author Matt Fitzgerald’s excellent book Racing Weight: How to Get Lean for Peak Performance:

A 160lbs runner expends 6.5% more energy than a 150lbs runner at the same pace.

Body fat and muscle tissue compete with each other for energy in the form of oxygen and fuel (glucose). With less body fat, more energy will be directed to your muscles.

For serious runners, this is an excellent book. It goes into detail on how to actually achieve fat loss.

(D) Lift Weights at a Gym

Lifting weights accomplishes three big goals for runners according to Jason Fitzgerald (a USATF-certified running coach):

It prevents injuries by strengthening muscles and connective tissues.

It helps you run faster by improving neuromuscular coordination and power.

It improves running economy, which is how efficiently a runner uses oxygen to sustain a given pace, by encouraging coordination and stride efficiency.

Here, we diverge into two paths, depending on if you’ve lifted before:

(i) You’re an Experienced Lifter

If you’re confident in your lifting abilities, then go do some lower and upper body days in a gym once or twice per week.

(ii) You’ve Never Been to a Gym Before

If you’re curious about lifting and don’t want to get injured, I recommend one of two options:

Hire a personal trainer for a few sessions.

It’s critical that your form is good while lifting weights, otherwise you could get injured. A personal trainer will set you up for success and teach you all the basics.

Ask a friend (who is an experienced lifter) for help.

One time a friend asked me to help her learn how to lift—I dropped everything in my life to bestow upon her all of my gym knowledge. I’m talking lifting technique, different exercises, hypertrophy knowledge, optimizing sleep and recovery—the whole gambit. She lost 5lbs of fat in two months and gained some muscle.

If you’re ever not feeling confident about performing a particular exercise, search “How to do [XYZ] exercise” on YouTube. I recommend Scott Herman. He’s an OG fitness creator who’s posted tons of simple 1-minute videos on how to perform nearly every exercise in the gym.

Note: gym people are often friendly and will help you if you have questions. If you ask someone for help and they’re a dick, ask someone else. If I was there, I would be happy to help you. 🙂

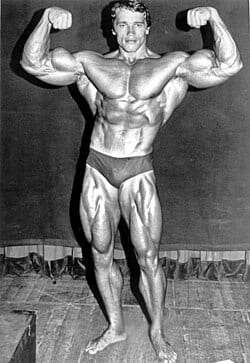

(iii) Can You Gain Too Much Muscle?

Increasing your overall muscle will help you become a more robust and faster runner…to a point. Bodybuilders with tons of extra muscle, just like people with excess fat, are also slowed down by gravity. If you want to run faster but you look like Arnold Schwarzenegger, consider losing some muscle.

Note: there is a difference in optimal body size depending on which running discipline you choose. Sprinters need more muscle to generate explosive force, whereas marathoners need to be as light weight as possible. Again, Matt Fitzgerald’s book Racing Weight: How to Get Lean for Peak Performance is an excellent guide for finding your optimal running weight.

Generally, weight lifting has helped me run faster for longer. Worth it.

(E) Temperature Affects Your Performance

50-60°F is optimal running weather. Any warmer than this, and your body will be forced to divert energy to cooling you down, instead of using that energy to run faster.

If your Zone 2 pace at 60°F is 9:00 minutes/mile, at 85°F your Zone 2 pace may be closer to 10:00 minutes/mile. This is why I prefer to run in the morning.

6. Sign up for a Race! Join a Run Club!

(A) Races

Once you’ve been running for a few months, consider signing up for a race—they’re fun! They’re an opportunity to test your limits and beat your personal record (PR).

Races are cheap. The simplest one is the 5K race (~3.1 miles) and usually costs ~$30-60. Marathons are more expensive at ~$100-300.

Here’s some advice from a veteran runner (me): don’t go out too fast. Most beginners make this mistake. If you plan to run your 5K at a consistent 8 minute/mile pace, when the starting gun sounds, don’t blaze out of the gate at a 6 minute/mile pace—you’ll drastically slow down from fatigue a mile or two into the race.

Want to perform well? Run negative splits. This means each mile should be progressively run faster. So your first mile could be run in 8:05 minutes, your second mile in 8:00 minutes, and your final mile in 7:55 minutes.

Post-race refreshments are free and usually include bananas, water, sports drinks, donuts, and more. Dig in, you earned it.

Overall, races are super fun, and runners are a supportive community. Highly recommend.

(B) Run Clubs

Live in a major city? You probably have an active run club in your area. Check for them on social media.

They’re free, filled with supportive/chill people who are into fitness, and it’s a good community (I’ve made friends through my run club; other people use them for dating).

7. Other Resources

For more on running, cardiovascular fitness, and lifting, check these out:

Racing Weight: How to Get Lean for Peak Performance

As previously mentioned, this is for achieving an ideal racing weight.

Running Science: Optimizing Training and Performance

Cool book that discusses the science of lots of niche running topics.

Born to Run: A Hidden Tribe, Superathletes, and the Greatest Race the World Has Never Seen

A fun book to read for inspiration.

Dr. Peter Attia on YouTube is a longevity expert and exercise fanatic. He’s created lots of content on Zone training and cardiovascular fitness.

Scott Herman has posted tons of simple 1-minute YouTube videos on how to perform nearly every exercise in the gym.

Hansons Marathon Method: Run Your Fastest Marathon the Hansons Way

I haven’t read this book, but one of my friends uses it as a guide to running marathons.

Note: marathon training is a bit specialized, but the same principles of running (ie: the 80⁄20 Principle and the 10% Rule) still apply.

8. Questions?

Have any questions? Google stuff, hire a running coach for a session or two, or leave a comment here—maybe I can help. 🙂

Am I missing anything? Leave a comment and I’ll consider adding it to this guide.

A lot of fitness advice is geared towards the safety/efficiency frontier—i.e. how to improve your fitness quickly but without too much injury risk. However, I’m personally equally interested in the comfort frontier. For example, if it’ll take me 3x longer to reach the same vo2 max by only ever running at <=70% of my max heart rate, I may still prefer that because it’s so much more pleasant to run at that exertion level.

How should a new runner handle the stabbing lung pain and overall feeling of being about to die? I have been unable to find any running speed that avoids these issues, even if it’s actually slower than my usual easy walking pace.

I’m a new-ish runner, and I think I had a similar problem when I started. I couldn’t jog slowly enough to not be immediately winded. I say immediately, but I could go for a few tens of seconds, I think? Less than a minute, and I would be surprised if it was even 30 seconds.

So, I started jogging for just long enough that I was touching the edge of being out of breath, but nothing really hurt, and then I would walk until I caught my breath and felt like I could do another short jog.

I still can’t jog for that long, but it’s way longer than before; and now I can go harder once or twice a week and it feels pleasantly intense rather than intensely painful.

Also, I don’t want to make it sound like a heart-rate monitor is necessary, because I don’t think it is, but I found that getting a (reliable) heart-rate monitor was really illuminating for me. In my case, there was initially just no jogging pace that would not put me well above zone 2. I experimented a bit and found that speed-walking was the only way I could stay in zone 2, and even then, I would slowly climb up into 3 by the end of my route. (Even more interesting was finding out that, for me, that “Gah! I’m dying!” feeling was me smacking into zone 5, which I can now use to calibrate the intensity of my harder runs.)

One of the more valuable insights I got from my heart-rate monitor was that I was trying to train at a way higher intensity than my fitness level allowed, which helped me chill out and stop injuring myself so often.

Good question. If you’re new to cardio and running is too painful for you, I’d suggest trying another less strenuous discipline like biking. As you get better at biking and your cardiovascular fitness improves, you could try running again at a slow pace.

Another option is to walk on an incline treadmill. You could increase the incline steepness each week or go for longer to improve.

I don’t know your fitness/general health. If you smoke, for example, I can’t imagine your lungs would feel good during a run.

It just takes time. Your diaphragm will eventually stop being so annoying.

This is/was me. I finally realized I couldn’t actually start with straight running, at least not for more than a minute or two at a time between walking. Things got better when I paid more attention to heart rate zones. Actual running will put me in the red zone way too fast, so I do things like really fast walking or treadmill incline to hit more moderate heart rate zones.

Good advice, but note that it doesn’t apply to all running, but specifically to street or track running. Trail is different in a few notable ways.

Major differences:

You want more of a forefoot strike. Your stride will be more like the motion of pedaling a bike, where your front foot is actually coming back in when it hits the ground. This is particularly important going downhill, as it reduces load on the knee & tendons. Likewise, if you leave a little room for your back foot to go back at the end of the stride, you can save yourself if you get snagged on a root or something.

Get a low heel-toe drop trail shoe to facilitate this stride, improve traction, and facilitate better ground feel.

Let your arms hang at your sides. It feels weird, but on longer runs (2 hrs+), your biceps will not like the bounce that comes with the bend.

Epistemic status: generally aligned with pro recommendations, injury free for 15 years, starting once I adopted these practices.

Injury free for 15 years is impressive. Nice!

What’s your opinion on starting to run with barefoot shoes? I’ve recently started using barefoot shoes due to overpronation and ankle instability (worked very well), so I’ve been a bit hesitant to use narrow cushioned shoes again for running. Any resources you recommend on this topic?

I took up running about a year ago, shortly after starting to wear bearfoot shoes. I only run in barefoot shoes and have had no problems. I suspect it helped that I “learned to run” in barefoot shoes, and that ordinarily one would have to change their stride to fit the shoe better, e.g. by landing mid foot instead of heel striking. I also, as I was a new runner, started off with extremely low volume (~10km a week), which also probably helped build foot strength.

I’m pretty happy overall, though am now tempted to get some proper running shoes for races, as the zero energy return is sad if you care about speed.

If you’re going to switch to barefoot shoes from cushioned shoes, go very slow and take it easy. There are a lot of foot muscles that are weaker by using cushioned shoes regularly. A sudden jump to barefoot shoes can easily lead to injury (I know some people who’ve gotten injured switching to barefoot shoes and immediately just doing their normal runs).

I’d recommend walking in them for a week, then light jogs for a couple weeks, before attempting any serious runs.

Sounds like they’re working well for you, though, so that’s good! If you want to switch back to cushioned shoes, the same slow process is required.

Yeah, I’ve ramped up slowly and did not get injured :) Although, I did not do any long runs in those yet.

Do you think the proper running technique would be different for barefoot shoes? I’ve heard that, with barefoot running, it’s better to go forefoot first to use the arch muscles to absorb the shock, or something like that.

I’m not the guy to ask. I’ve never tried barefoot shoes.

Your explanation for forefoot striking makes sense to me.

I feel like this conflates overstriding with heel-striking[1]. Overstriding—one’s feet land too much in front of one’s center of mass. Even consulting your own image, the runner marked as ‘mid-foot striking’ could be heel-striking without changing anything in the overall posture.[2] Though, I agree that mid-foot striking is still definitely better than heel-striking on net.

Specifically, I think the claims about braking and excessive stress are false for heel-striking when decoupled from overstriding.

I know plenty of runners with good running technique and years of experience who are lifelong heel-strikes. Though, I’m a forefoot to midfoot striker myself.

Agreed, thanks! I changed the preceding paragraph to reflect this:

In general, a 10-16° forward lean should take care of both heel striking and overstriding.

I currently do Cardio Interval Training, around 2 to 3 times a week.

More specifically, I typically do 3 or 4 cycles of sprinting to get my heart rate above 170 bpm, keeping my HR above 170 for about 50 seconds, and then slowing to a brisk walk for 120 seconds. (I’m gradually increasing the intense periods and shrinking the moderate-rest periods.) The I’m aiming for a quick, intense, cardiovascular exercise for optimizing my nighttime HRV.

Should I be concerned about doing that as frequently as every other day?

No you shouldn’t be concerned. What you’re doing is a form of HIIT training (ie: High Intensity Interval Training), which is great for cardiovascular health and boosting your metabolism.

While you’re choosing to perform HIIT with running, it’s not really running in the general sense that I’ve described in this post. For example, you could perform HIIT with biking, or jump rope, or swimming; anything to increase your heart rate for the duration of some intervals. The sport of running is more about completing longer distances for a sustained time.

As long as you feel healthy and nothing hurts, I don’t see anything wrong with doing HIIT as frequently as every other day for your general health. I like your approach of gradually increasing the intensity and shrinking the rest periods. Seems good!

readers of this post may also enjoy the simpler following post: how to run without all the pesky agonizing pain

I prefer to toe-strike to reduce knee and hip impact. Is this a bad idea?

Toe-striking is preferable for sprinters since they want to spend as little time on the ground as possible. Plus, sprinters are starting from a crouched position which forces them to toe-strike initially.

For casual running, toe-striking places more pressure on the calves. The calves are a smaller muscle group compared to your glutes, hips, quads, and hamstrings (which can absorb more impact).

If you toe-strike and you’re pain-free, then there’s no problem with it. If, however, you’re feeling pain and want to change your foot strike position, do so very slowly (over a few weeks with reduced speed). Any changes to foot position introduces the use of new muscles in the feet that are not used to that type of impact.

Thanks. I used to tumble, so my calves and Achilles are pretty robust. Having an extra hinge to spring from improves comfort.

Not in my experience, which is substantial, but perhaps specific to me.

This is a great writeup! I’d consider myself a pretty experienced runner, but the technique for getting rid of side stitches was new to me.

If you’re a beginner, you can probably get away with stretching the 10% rule a little bit. If you’re only running 3 miles per week (mpw), you don’t need to limit yourself to 3.3 miles the next week − 4 is probably fine, even though that’s a 33% increase. ~10 mpw is where I’d start implementing the 10% rule.

That said, I cannot emphasize enough how important it is to build up your running volume slowly and carefully. I’ve had two overuse injuries in the last year: one from increasing mileage too quickly, the other from increasing intensity too quickly.

My cross country coach in high school taught me the technique for side stitches. Sucks to do in the moment, but it works every time.

100% agreed on the mileage. The 10% Rule becomes more important once you cross that 10 miles/week threshold.