[Intro to brain-like-AGI safety] 10. The technical alignment problem

(Last revised: January 2026. See changelog at the bottom.)

10.1 Post summary / Table of contents

Part of the “Intro to brain-like-AGI safety” post series.

In this post, I (finally) discuss the technical alignment problem for brain-like AGIs—i.e., the problem of how to make an AGI such that its motivations are what the AGI designers had in mind. (More on what “alignment” means in §10.1.1 just below.)

The alignment problem is (I claim) the lion’s share of the technical AGI safety problem (§1.2). I won’t defend that claim here—I’ll push it off to the next post, which will cover exactly how AGI safety is related to AGI alignment, including the edge-cases where they come apart.[1]

This post is about the alignment problem, not its solution. What are the barriers to solving the alignment problem? Why do straightforward, naïve approaches seem to be insufficient? And then I’ll talk about possible solution approaches in later posts. (Spoiler: nobody knows how to solve the alignment problem, and neither do I.)

Table of contents

In §10.2, I’ll define “inner alignment” and “outer alignment” in the context of our brain-like-AGI motivation system. To oversimplify a bit:

If you prefer neuroscience terminology: “Outer alignment” entails having “innate drives” (cf. §3.4.2) that fire in a way that reflects how well the AGI is following the designer’s intentions. “Inner alignment” is a situation where an imagined plan (built out of concepts, a.k.a. latent variables, in the AGI’s world-model) has a valence that accurately reflects the innate drives which would be triggered by that plan.

If you prefer reinforcement learning terminology: “Outer alignment” entails having a ground-truth reward function that spits out rewards that agree with what we want. “Inner alignment” is having a learned value function that estimates the value of a plan in a way that agrees with its eventual reward.

In the AGI alignment literature, failures of outer alignment are also called “specification gaming”, while failures of inner alignment are also called “goal misgeneralization”.

In §10.3, I’ll talk about two key issues that make alignment hard in general (whether “inner” or “outer”):

The first is “Goodhart’s Law”, which implies that an AGI whose motivation is just a bit off from what we intended can nevertheless lead to outcomes that are wildly different from what we intended.

The second is “Instrumental Convergence”, which says that a wide variety of possible AGI motivations—including generic, seemingly-benign motivations like “I want to invent a better solar cell”—will lead to AGIs which want to do catastrophically-bad things like escape human control, self-reproduce, gain resources and influence, act deceptively, and kill everyone (cf. §1.6).

In §10.4, I’ll discuss two challenges to achieving “outer alignment”: first, translating our design intentions into machine code, and second, the possible inclusion of innate drives / rewards for behaviors that are not exactly what we ultimately want the AGI to do, such as satisfying its own curiosity (see §3.4.3).

In §10.5, I’ll discuss numerous challenges to achieving “inner alignment”, including reward ambiguity, bad credit assignment, “ontological crises”, and the AGI manipulating itself or its training process.

In §10.6, I’ll discuss some reasons that “outer alignment” and “inner alignment” should probably not be viewed as two independent problems with two independent solutions. For example, neural network interpretability would cut through both layers.

10.1.1 What does “alignment” even mean?

The humans programming AGI will have some ideas about what they want that AGI’s motivations to be. I define “the technical alignment problem” as the challenge of building AGI that actually has those motivations, via appropriate code, training environments, and so on.

This definition is deliberately agnostic about what motivations the AGI designers are going for.

Other researchers are not agnostic, but rather think that the “correct” design intentions (for an AGI’s motivation) are obvious, and they define the word “alignment” accordingly. Three common examples are

(1) “I am designing the AGI so that, at any given point in time, it’s trying to do what its human supervisor wants it to be trying to do right now.”

This AGI would be “aligned” to the supervisor’s intentions; I might refer to this vision as “the Paul Christiano version of corrigibility”.

(2) “I am designing the AGI so that it shares the values of its human supervisor.

This AGI would be “aligned” to the supervisor; I might refer to this vision as “ambitious value learning”.

(3) “I am designing the AGI so that it shares the collective values of humanity.”

This AGI would be “aligned” to humanity; I might refer to this vision as “Coherent Extrapolated Volition”.

I’m using “alignment” in this agnostic way because I think that the “correct” intended AGI motivation is still an open question.

For example, maybe it will be possible to build an AGI that really just wants to do a specific, predetermined, narrow task (e.g. design a better solar cell), in a way that doesn’t involve taking over the world etc. Such an AGI would not be “aligned” to anything in particular, except for the original design intention. But I still want to use the term “aligned” when talking about such an AGI.

10.2 Inner & Outer (mis)alignment

10.2.1 Definition

Here, yet again, is that figure from Post #6, now with some helpful terminology (blue) and a little green face at the bottom left:

I want to call out three things from this diagram:

The designer’s intentions (green face): Perhaps there’s a human who is programming the AGI; presumably they have some idea in their head as to what the AGI is supposed to be trying to do. That’s just an example; it could alternatively be a team of humans who have collectively settled on a specification describing what the AGI is supposed to be trying to do. Or maybe someone wrote a 700-page philosophy book entitled “What Does It Mean For An AGI To Act Ethically?”, and the team of programmers is trying to make an AGI that adheres to the book’s description. It doesn’t matter here. I’ll stick to “one human programming the AGI” for conceptual simplicity.[2]

The human-written source code of the Steering Subsystem: (See Post #3 for what the Steering Subsystem is, and Post #8 for why I expect it to consist of more-or-less purely human-written source code.) The most important item in this category is the “reward function” for reinforcement learning, which provides ground truth for how well or poorly things are going for the AGI. In the biology case, the reward function would specify “innate drives” (see Post #3) like pain being bad and eating-when-hungry being good. In the terminology of our series, the “reward function” governs when and how the “actual valence” signal enters “override mode”—see Post #5.

The Thought Assessors, trained from scratch by supervised learning algorithms: (See Post #5 for what Thought Assessors are and how they’re trained.) These take a certain “thought” from the thought generator, and guess what Steering Subsystem signals it will lead to. An especially important special case is the value function (a.k.a. “learned critic”, a.k.a. “valence Thought Assessor”), which sends out a “valence guess” signal based on supervised learning from all the “actual valence” signals over the course of life experience.

Correspondingly, there are two kinds of “alignment” in this type of AGI:

Outer alignment is alignment between the designer’s intentions and the Steering Subsystem source code. In particular, if the AGI is outer-aligned, the Steering Subsystem will output higher (more positive) reward signals when the AGI is satisfying the designer’s intentions, and lower (more negative) reward signals when it’s not.

In other words, outer alignment is the question: Are the AGI’s “innate drives” driving the AGI to do what the designer had intended?

Inner alignment is alignment between the Steering Subsystem source code and the Thought Assessors. In particular, if the AGI is inner-aligned, and the Thought Generator proposes some plan, then the value function should reflect the reward actually expected from executing that plan.

In other words, inner alignment is the question: Do the set of positive-valence concepts in the AGI’s world-model line up with the set of courses-of-action that would satisfy the AGI’s “innate drives”?

If an AGI is both outer-aligned and inner-aligned, we get intent alignment—the AGI is “trying” to do what the programmer had intended for it to try to do. Specifically, if the AGI comes up with a plan “Hey, maybe I’ll do XYZ!”, then its Steering Subsystem will judge that to be a good plan (and actually carry it out) if and only if it lines up with the programmer’s design intentions.

Thus, an intent-aligned AGI will not deliberately hatch a clever plot to take over the world and kill all the humans. Unless, of course, the designers were maniacs who wanted the AGI to do that! But that’s a different problem, out-of-scope for this series—see §1.2.

Unfortunately, neither “outer alignment” nor “inner alignment” happens automatically. Quite the contrary: by default there are severe problems on both sides. It’s on us to figure out how to solve them. In this post I’ll go over some of those problems. (Note that this is not a comprehensive list, and also that some of these things overlap.)

10.2.2 Warning: two uses of the terms “inner & outer alignment”

As mentioned in Post #8, there are two competing development models that could get us to brain-like AGI. They both can be discussed in terms of outer and inner alignment, and they both can be exemplified by the case of human intelligence, but the details are different in the two cases! Here’s the short intuitive version:

Anyway, the terms “inner alignment” and “outer alignment” first originated in the “Evolution from scratch” model, specifically in the paper Risks From Learned Optimization (2019). I took it upon myself to reuse the terminology for discussing the “genome = ML code” model. I still think that was the right call—I think that the usages have a ton in common, and that they’re more similar than different. But still, don’t get confused!

10.2.3 The assumption of “behaviorist rewards”

“Behaviorist rewards” is a term I made up for an RL reward function which depends only on externally-visible actions, behaviors, and/or the state of the world. By contrast, non-behaviorist rewards would be if the ground-truth reward function output depends also on what the agent is thinking.

The name is a reference to “behaviorism”, a school-of-thought in the early-to-mid 20th century that (to caricature a bit) rejected all discussion of thoughts, feelings, etc., instead focusing exclusively on an animal’s externally-visible behavior.

Examples of behaviorist rewards include almost every reward function in the entire RL literature: think of winning at chess, beating a videogame, balancing a pole, etc. Indeed, standard formalizations of RL, such as the POMDP framework, don’t even acknowledge the existence of non-behaviorist rewards!

Now, I don’t think behaviorist rewards are a good plan for brain-like AGI. Quite the contrary: my current belief is that behaviorist reward functions universally lead to egregiously misaligned AGIs, and that non-behaviorist reward functions are our only hope. That’s a bold claim that I won’t defend here, but see my post “Behaviorist” RL reward functions lead to scheming (2025) for my thinking.

What would non-behaviorist rewards look like? Curiosity drive[3] is an example, although it’s an example that makes safety problems worse rather than better (§10.4.2 below). Here’s a better example: there could be an interpretability system scrutinizing the internals of the Thought Generator, and that system could directly influence the ground-truth rewards. Many plans in this category will still fail (see Yudkowsky’s “List of Lethalities” (2022), item 27), but there are also promising directions. Indeed, I argued in §9.6 that the various Thought Assessors comprise exactly such an interpretability system, and accordingly, non-behaviorist rewards are involved in both human social instincts (Post 13) and the alignment ideas in Post 14.

Nevertheless, I’ll mostly assume behaviorist rewards in this post, as a common and important special case. Everything in the post also applies to non-behaviorist rewards, except for the categorization of problems into “inner alignment” versus “outer alignment”, which sometimes breaks down for non-behaviorist rewards—more on this in §10.6.2 below.

10.3 Issues that impact both inner & outer alignment

10.3.1 Goodhart’s Law

Goodhart’s Law (Wikipedia, Rob Miles youtube) states that there’s a world of difference between:

Optimize exactly what we want, versus

Step 1: operationalize exactly what we want, in the form of some reasonable-sounding metric(s). Step 2: optimize those metrics.

In the latter case, you’ll get whatever is captured by those metrics. You’ll get it in abundance! But you’ll get it at the expense of everything else you value!

Thus, the story goes, a Soviet shoe factory got a performance bonus based on how many shoes they made, from a limited supply of leather. Naturally, they started making huge numbers of tiny kids shoes.

By the same token, we’ll presumably write source code that somehow operationalizes what we want the AGI’s motivation to be. The AGI will be motivated by that exact operationalization, as an end in itself, even if we meant for its motivation to be something subtly different.

Goodhart’s Law shows up with alarming frequency in AI. One time, someone set up an evolutionary search for image classification algorithms, and it turned up a timing-attack algorithm, which inferred the image labels based on where they were stored on the hard drive. Someone else trained an AI algorithm to play Tetris, and it learned to survive forever by pausing the game. Etc. See gwern.net/Tanks for those references, plus dozens more.

10.3.1.1 Didn’t LLMs solve the Goodhart’s Law problem?

When I first published this series in early 2022, I didn’t really need to defend the idea that Goodhart’s Law is an AI failure mode, because it was ubiquitous and obvious. We want AIs that find innovative, out-of-the-box solutions to problems (like winning at chess or making money), and that’s how we build AIs, so of course that’s what they do. And there isn’t a principled distinction between “meet the spec via a clever solution that I wouldn’t have thought of”, versus “meet the spec by exploiting a loophole in how the spec is operationalized”. You can’t get the former without the latter. This is obvious in theory, and equally obvious in practice. Everyone in AI had seen it with their own eyes.

…But then LLM chatbots came along, and gave rise to the popular idea that “AI that obeys instructions in a common-sense way” is a solved problem. Ask Claude Code to ensure that render.cpp has no memory leaks, and it won’t technically “satisfy” the “spec” by deleting all of the code from the file. Well, actually, it might sometimes; I don’t want to downplay LLM alignment challenges. See Soares & Yudkowsky FAQ, “Aren’t developers regularly making their AIs nice and safe and obedient?” for a pessimist’s case.

But more importantly, regardless of whether it’s a solved problem for today’s LLMs, it is definitely not a solved problem for brain-like AGI, nor for the more general category of “RL agents”. They are profoundly different algorithm classes. You can’t extrapolate from one to the other.

See my post Foom & Doom 2: Technical alignment is hard (2025) for a deep-dive into how people get LLMs to (more-or-less) follow common-sense instructions without egregious scheming and deception, and why we won’t be able to just use that same trick for brain-like AGI. The short version is that LLM capabilities come overwhelmingly from imitation learning. “True” imitation learning is weird, and profoundly different from everyday human social imitation, or indeed anything else in biology; I like to call it “the magical transmutation of observations into behavior” to emphasize its weirdness. Anyway, I claim that true imitation learning has alignment benefits (LLMs can arguably obey common-sense instructions), but those benefits are inexorably yoked to capabilities costs (LLMs can’t really “figure things out” beyond the human distribution, the way that societies of humans can, as I discuss in my “Sharp Left Turn” post (2025)). So it’s a trick that won’t help us with brain-like AGI. Again, more details in that link.

10.3.1.2 Understanding the designer’s intention ≠ Adopting the designer’s intention

Maybe you’re thinking: “That’s nonsense. I can see with my own eyes that LLM chatbots don’t do the Goodhart’s Law thing all the time. But I disagree that the explanation lies in some abstruse details of their training setup. Instead, the explanation is that LLM chatbots can understand what we mean! So by the same token, maybe it’s true that the dumb RL agents and evolutionary search algorithms of today engage in Goodhart’s Law trickery. But the brain-like AGIs of tomorrow would be smart enough to understand what we meant for its motivation to be.

My response is: Yes, of course they will. But you’re asking the wrong question. An AGI can understand our intended goals, without adopting our intended goals. Consider this amusing thought experiment:

If an alien species showed up in their UFOs, said that they’d created us but made a mistake and actually we were supposed to eat our children, and asked us to line up so they could insert the functioning child-eating gene in us, we would probably go all Independence Day on them. —Scott Alexander (2015)

(Suppose for the sake of argument that the aliens are telling the truth, and can prove it beyond any doubt.) Here, the aliens told us what they intended for our goals to be, and we understand those intentions, but we don’t adopt them by allowing ourselves to be converted into enthusiastic child-eaters.

10.3.1.3 Why not make an AGI that adopts the designer’s intentions?

Is it possible to make an AGI that will “do what we mean and adopt our intended goals”? Yeah, probably. And the obvious way to do that would be to program the AGI so that it’s motivated to “do what we mean and adopt our intended goals”.

Unfortunately, that maneuver doesn’t eliminate Goodhart’s law—it just shifts it.

After all, we still need to write source code which, interpreted literally, somehow leads to an AGI which is motivated to “do what we mean and adopt our intended goals”. Writing this code is very far from straightforward, and Goodhart’s law is ready to pounce if we get it wrong.

(Note the chicken-and-egg problem: if we already had an AGI which is motivated to “do what we mean and adopt our intended goals”, we could just say “Hey AGI, from now on, I want you to do what we mean and adopt our intended goals”, and we would never have to worry about Goodhart’s law! Alas, in reality, we need to start from literally-interpreted source code.)

So how do you operationalize “do what we mean and adopt our intended goals”, in such a way that it can be put it into source code? Well, hmm, maybe we can build a “Reward” button, and I can press it when the AGI “does what I mean and adopts my intended goals”? Nope! Goodhart’s law again! We could wind up with an AGI that tortures us unless we press the reward button. (See Reward button alignment (2025), and more broadly “Behaviorist” RL reward functions lead to scheming (2025).)

10.3.2 Instrumental convergence

Goodhart’s law above suggests that installing an intended goal will be very hard. Next up is “instrumental convergence” (Rob Miles video) which, in a cruel twist of irony, says that installing a bad and dangerous goal will be so easy that it can happen accidentally!

Let’s say an AGI has a real-world goal like “Cure cancer”. Good strategies towards this goal may involve pursuing certain instrumental sub-goals such as:

Preventing itself from being shut down

Preventing itself from being reprogrammed to not cure cancer

Increasing its own knowledge and capabilities

Gaining money & influence

Building more AGIs with the same goal of curing cancer, including by self-replication

As long as the AGI has preferences about what happens in the future, and can flexibly and strategically make plans to bring about those preferences, it’s a safe bet that those plans will involve some or all of the above bullet points. This observation is called “instrumental convergence”, because an endless variety of terminal goals can “converge” onto a limited set of these dangerous instrumental goals.

10.3.2.1 Walking through an example of instrumental convergence

Imagine what’s going on in the AGI’s cognition, as it sees its programmer opening up her laptop—remember, we’re assuming that the AGI is motivated to cure cancer.

AGI thought generator: I will allow myself to be reprogrammed, and then I won’t cure cancer, and then it’s less likely that cancer will get cured.

AGI Thought Assessors & Steering Subsystem: Bzzzt! Bad thought! Throw it out and come up with a better one!

AGI thought generator: I will trick the programmer into not reprogramming me, and then I can continue trying to cure cancer, and maybe succeed.

AGI Thought Assessors & Steering Subsystem: Ding! Good thought! Keep that one in your head, and keep thinking follow-up thoughts, and executing corresponding actions.

10.3.2.2 Is human self-preservation an example of instrumental convergence?

The word “instrumental” is important here—we’re interested in the situation where the AGI is trying to pursue self-preservation and other goals as a means to an end, rather than an end in itself.

People sometimes get confused because they analogize to humans, and it turns out that human self-preservation can be either an instrumental goal or a terminal goal:

Suppose someone says “I really want to stay alive as long as possible, because life is wonderful”. This person seems to have self-preservation as a terminal goal.

Suppose someone says: “I’m old and sick and exhausted, but dammit I really want to finish writing my novel and I refuse to die until it’s done!” This person has self-preservation as an instrumental goal.

In the AGI case, we’re typically thinking of the latter case: for example, the AGI wants to invent a better solar cell, and incidentally winds up with self-preservation as an instrumental goal.

It’s also possible to make an AGI with self-preservation as a terminal goal. It’s a terrible idea, from an AGI-accident-risk perspective. But it’s presumably possible. In that case, the AGI’s self-preservation behavior would NOT be an example of “instrumental convergence”.

I could make similar comments about human desires for power, influence, knowledge, etc.—they might be directly installed as innate drives by the human genome, I don’t know. But whether they are or not, they can also appear via instrumental convergence, and that’s the harder problem to solve for AGIs.

10.3.2.3 Motivations that don’t lead to instrumental convergence

Instrumental convergence is not inevitable in every possible motivation. It comes from AIs having preferences about the state of the world in the future—and most centrally, the distant future (say, weeks or months or longer)—such that investments in future options have time to pay themselves back. These are called “consequentialist” preferences.

Given that, one extreme position is to say “well OK, if ‘AGIs with consequentialist preferences’ leads to bad and dangerous things, then fine, we’ll build AGIs without consequentialist preferences!”. Alas, I don’t think that’s a helpful plan. The minor problem is that we could try to ensure that the AGI preferences are not consequentialist, but fail, because technical alignment is hard. The much bigger problem is that, even if we succeed, the AGI won’t do anything of note, and will be hopelessly outcompeted and outclassed when the next company down the street, with a more cavalier attitude about safety, makes an AGI that does have consequentialist preferences. After all, it’s hard to get things done except by wanting things to get done. For more on both these points, see my post Thoughts on “Process-Based Supervision” / MONA (2023), §5.2–5.3.

Then the opposite extreme position is to say “That’s right! If AGI is powerful at all, it will certainly have exclusively consequentialist preferences. So we should expect instrumental convergence to bite maximally hard.” But I don’t think that’s right either—see my post Consequentialism & corrigibility (2021). Humans have a mix of consequentialist and non-consequentialist preferences, but societies of humans were nevertheless capable of developing language, science, and the global economy from scratch. As far as I know, brain-like AGI could be like that too. But we need to figure out exactly how.

10.3.3 Goodhart & Instrumental Convergence: putting them together

10.3.3.1 “The usual agent debugging loop”, and its future catastrophic breakdown

I was talking about the ubiquity of Goodhart’s Law just above. You might be wondering: “If Goodhart’s Law is such an intractable problem, why are there thousands of impressive RL results on arXiv right now?” The answer is “the usual agent debugging loop”. It’s applicable to any system involving RL, model-based planning, or both. Here it is:

Step 1: Train the AI agent, and see what it does.

Step 2: If it’s not doing what you had in mind, then turn it off, change something about the reward function or training environment, etc., and then try again.

For example, if the Coast Runners boat is racking up points by spinning in circles while on fire, but we wanted the boat to follow the normal race course, then OK maybe let’s try editing the reward function to incorporate waypoints, or let’s delete the green blocks from the environment, etc.

That’s a great approach for today, and it will continue being a great approach for a while. But eventually it will start failing in a catastrophic and irreversible way—and this is where instrumental convergence comes in.

The problem is: it will eventually become possible to train an AI that is so good at real-world planning, that it can make plans that are resilient to potential problems—and if the programmers are inclined to shut down or edit the AI under certain conditions, then that’s just another potential problem that the AI will incorporate into its planning process!

…So if a sufficiently competent AI is trying to do something the programmers didn’t want, the normal strategy of “just turn off the AI, or edit it, to try to fix the problem” stops working. The AI will anticipate that this programmer intervention is a possible obstacle to what it’s trying to do, and make a plan resilient to that possible obstacle. This is no different than any other aspect of skillful planning—if you expect that the cafeteria might be closed today, then you’ll pack a bag lunch.

In the case at hand, a “resilient” plan might look like the programmers not realizing that anything has gone wrong with the AI, because the AI is being deceptive about its plans and intentions. And meanwhile, the AI is gathering resources and exfiltrating itself so that it can’t be straightforwardly turned off or edited, etc.

The upshot is: RL researchers today, and brain-like AGI researchers in the future, will be able to generate more and more impressive demos, and get more and more profits, for quite a while, even if neither they nor anyone else makes meaningful progress on this technical alignment problem. But that would only be up to a certain level of capability. Then it would flip sharply into being an existential threat.

10.3.3.2 Summary

So in summary, Goodhart’s Law says we’ve learned that we really need to get the right motivation into the AGI, or else the AGI will probably do a very different thing than what we intended. Then Instrumental Convergence twists the knife by saying that the thing the AGI will want to do is not only different but probably catastrophically dangerous, involving a motivation to escape human control and seize power. At the same time, our normal techniques for debugging AI motivations will break down, because the AGIs will be telling us what we want to hear. And loss of control could happen all at once, just as humans tend not to launch coups until they are reasonably confident that their attempts will succeed.

Now, we don’t necessarily need the AGI’s motivation to be exactly right in every way, but we do at least need it to be motivated to be “corrigible”, in the broad sense of wanting us to remain able to turn it off, and to be apprised of the true situation and in control. Unfortunately, installing any motivation seems to be a messy and fraught process (for reasons below). Aiming for a corrigible motivation is probably a good idea, but if we miss, we’re in big trouble.

In the next two sections, we move into more specific reasons that outer alignment is difficult, followed by reasons that inner alignment is difficult.

10.4 Challenges to achieving outer alignment

10.4.1 Translation of our intentions into machine code

Remember, we’re starting with a human who has some idea of what the AGI should do (or a team of humans with an idea of what the AGI should do, or a 700-page philosophy book entitled “What Does It Mean For An AGI To Act Ethically?”, or something). We need to somehow get from that starting point, to machine code for the Steering Subsystem that outputs a ground-truth reward signal. How?

My assessment is that, as of today, nobody has a clue how to translate that 700-page philosophy book into machine code that outputs a ground-truth reward signal. There are ideas in the AGI safety literature for how to proceed, but they don’t look anything like that. Instead, it’s as if researchers threw up their hands and said: “Maybe this isn’t exactly the #1 thing we want the AI to do in a perfect world, but it’s good enough, and it’s safe, and it’s not impossible to operationalize as a ground-truth reward signal.”

For example, take AI Safety Via Debate. That’s the idea that maybe we can make an AGI that’s “trying” to win a debate, against a copy of itself, about whatever question you’re interested in (“Should I wear my rainbow sunglasses today?”).

Naïvely, AI Safety Via Debate seems absolutely nuts. Why set up a debate between an AGI that’s arguing for the wrong answer versus an AGI that’s arguing for the right answer? Why not just make one AGI that tells you the right answer? Well, because of the exact thing I’m talking about in this section. In a debate, there’s a straightforward way to generate a ground-truth reward signal, namely “+1 for winning”. By contrast, nobody knows how to make a ground-truth reward signal for “telling me the right answer”, when I don’t already know the right answer.[4]

Continuing with the debate example, the capabilities story is “hopefully the debater arguing the correct answer tends to win the debate”. The safety story is “two copies of the same AGI, in zero-sum competition, will kinda keep each other in check”. The latter story is (in my opinion) rather dubious.[5] But I still like bringing up AI Safety Via Debate as a nice illustration of the weird, counterintuitive directions that people go in order to mitigate the outer alignment problem.

AI Safety Via Debate is just one example from the literature; others include recursive reward modelling, iterated amplification, Hippocratic time-dependent learning, etc.

Presumably we want humans in the loop somewhere, to monitor and continually refine & update the reward signals. But that’s tricky because (1) human-provided data is expensive, and (2) humans are not always capable (for various reasons) of judging whether the AGI is doing the right thing—let alone whether it’s doing the right thing for the right reasons.

There’s also Cooperative Inverse Reinforcement Learning (CIRL) and variants thereof, which entail learning the human’s goals and values by observing and interacting with the human. The problem with CIRL, in this context, is that it’s not a ground-truth reward function at all! It’s a desideratum! In the brain-like AGI case, with the learned-from-scratch world model (Post #2), there are some quite tricky symbol-grounding problems to solve before we can actually do CIRL (related discussion), more on which in later posts.[6]

10.4.2 Curiosity drive, and other dangerous capability-related rewards

As discussed in §3.4.3, endowing our learning algorithms with an innate curiosity drive seems like it may be necessary for it to eventually develop into a powerful AGI. Unfortunately, it’s also dangerous. Why? Because if an AGI is motivated to satisfy its own curiosity, it may do so at the expense of other things we care about much more, like human flourishing and so on.

(For example, if the AGI is sufficiently curious about patterns in digits of π, it might feel motivated to wipe out humanity and plaster the Earth with supercomputers calculating ever more digits!)

As luck would have it, I also argued in §3.4.3 that we can probably turn the curiosity drive off when an AGI is sufficiently intelligent, without harming its capabilities—indeed, turning it off should eventually help its capabilities! So this isn’t as bad a problem as other aspects of alignment, where we have no plan at all. That said, future programmers may still mess this up, e.g. by waiting too long before turning it off. How long is too long? Worryingly, that might need to be set empirically, by trial-and-error, a.k.a. some kind of hyperparameter sweep. But how do we safely do hyperparameter sweeps on AGIs that might be trying to deceive us and escape from our testing frameworks? This is a gnarly problem, where I don’t have great answers (but see §15.2.2.2).

10.5 Challenges to achieving inner alignment

10.5.1 Ambiguity in the reward signals (including wireheading)

There are many different possible value functions (a.k.a. trained valence Thought Assessors) that agree with the actual history of ground-truth reward signals, but which each generalize out-of-distribution in their own ways. To take an easy example, whatever is the history of ground-truth reward signals, the wireheading value function (“I like it when there’s a ground-truth reward signal”—see §9.4) is always trivially consistent with it!

Or compare “negative reward for lying” to “negative reward for getting caught lying”!

This is an especially severe problem for AGI because the space of all possible thoughts / plans is bound to extend far beyond what the AGI has already seen. For example, the AGI could conceive of the idea of inventing a new invention, or the idea of killing its operator, or the idea of hacking into its own ground-truth reward signal, or the idea of opening a wormhole to an alternate dimension! In all those cases, the value function is given the impossible task of evaluating a thought it’s never seen before. It does the best it can—basically, it pattern-matches bits and pieces of the new thought to various old thoughts on which it has ground-truth data. This process seems fraught!

In other words, the very essence of intelligence is coming up with new ideas, and that’s exactly where the value function is most out on a limb and prone to error.

10.5.2 Credit assignment failures

I discussed “credit assignment” in §9.3. In this case, “credit assignment” is when the value function updates itself by (something like) Temporal Difference (TD) learning from ground-truth-reward. The underlying algorithm, I argued, relies on the assumption that the AGI has properly modeled the cause of the reward. For example, if Tessa punches me in the stomach, it might make me a bit viscerally skittish when I see her in the future. But if I had mistaken Tessa for her identical twin Jessa, I would be viscerally skittish around Jessa instead. That would be a “credit assignment failure”. A nice example of credit assignment failure is human superstitions.

The previous subsection (ambiguity in the reward signal) is one reason that credit assignment failures could happen. There are other reasons as well. For example, credit can only go to concepts in the AGI’s world-model (§9.3), and it could be the case that the AGI’s world-model simply has no concept that aligns well with the ground-truth reward function. In particular, that would certainly be the case early on in training, when the AGI’s world-model has no concepts for anything whatsoever—see Post #2.

It gets even worse if a self-reflective AGI is motivated to deliberately cause credit assignment failures. The reason that the AGI might wind up with such a motivation is discussed below (§10.5.4).

10.5.3 Ontological crises

An ontological crisis is when part of an agent’s world-model needs to be re-built on a new foundation. A typical human example is if a religious person has a crisis of faith, and then finds that their previous goals (e.g. “get into heaven”) are incoherent (“but there is no heaven!”)

As an AGI example, let’s say I build an AGI with the goal “Do what I, the human, want you to do”. Maybe the AGI starts with a primitive understanding of human psychology, and thinks of me as a monolithic rational agent. So then “Do what I, the human, want you to do” is a nice, well-defined goal. But then later on, the AGI develops a more sophisticated understanding of human psychology, and it realizes that I have contradictory goals, and context-dependent goals, and I have a brain made of neurons and so on. Maybe the AGI’s goal is still “Do what I, the human, want you to do”, but now it’s not so clear what exactly that refers to, in its updated world model. How does that shake out? I think it’s not obvious.

An unfortunate aspect of ontological crises (and not unique to them) is that you don’t know when they will strike. Maybe you’re seven years into deployment, and the AGI has been scrupulously helpful the whole time, and you’ve been trusting the AGI with more and more autonomy, and then the AGI then happens to be reading some new philosophy book, and it converts to panpsychism (nobody’s perfect!), and as it maps its existing values onto its reconceptualized world, it finds itself no longer valuing the lives of humans over the lives of rocks, or whatever.

10.5.4 Manipulating itself and its learning process

10.5.4.1 Misaligned higher-order preferences

Suppose that we want our AGI to obey the law. We can ask two questions:

Question 1: Does the AGI assign positive value to the concept “obeying the law”, and to plans that entail obeying the law?

Question 2: Does the AGI assign positive value to the self-reflective concept “I value obeying the law”, and to plans that entail continuing to value obeying the law?

If the answers are yes and no respectively (or no and yes respectively), that would be the AGI analog of an ego-dystonic motivation. (Related discussion.) It would lead to the AGI feeling motivated to change its motivation, for example by hacking into itself. Or if the AGI is built from perfectly secure code running on a perfectly secure operating system (hahaha), then it can’t hack into itself, but it could still probably manipulate its motivation by thinking thoughts in a way that manipulates the credit-assignment process (see discussion in §9.3.3).

If the answers to questions 1 & 2 are yes and no respectively, then we want to prevent the AGI from manipulating its own motivation. On the other hand, if the answers are no and yes respectively, then we want the AGI to manipulate its own motivation!

(There can be even-higher-order preferences too: in principle, an AGI could wind up hating the fact that it values the fact that it hates the fact that it values obeying the law.)

In general, should we expect misaligned higher-order preferences to occur?

On the one hand, suppose we start with an AGI that wants to obey the law, but has no particular higher-order preference one way or the other about the fact that it wants to obey the law. Then (it seems to me), the AGI is very likely to also wind up wanting to want to obey the law (and wanting to want to want to obey the law, etc.). The reason is: the primary obvious consequence of “I want to obey the law” is “I will obey the law”, which is already desired. Remember, the AGI can do means-end reasoning, so things that lead to desirable consequences tend to become themselves desirable.

On the other hand, humans do in fact have higher-order preferences that contradict object-level preferences all the time. So there has to be some context in which that pattern occurs “naturally” in humans. I think it almost always involves pride or shame in how other people see us. See my discussion in “6 reasons why ‘alignment-is-hard’ discourse seems alien to human intuitions, and vice-versa” (2025), §0.3.

10.5.4.2 Motivation to prevent further value changes

As the AGI continually learns (§8.2.2), especially via credit assignment (§9.3), the value function (a.k.a. valence Thought Assessor) keeps changing. This isn’t optional: remember, the value function start out random! This continual learning is how we sculpt the motivation in the first place!

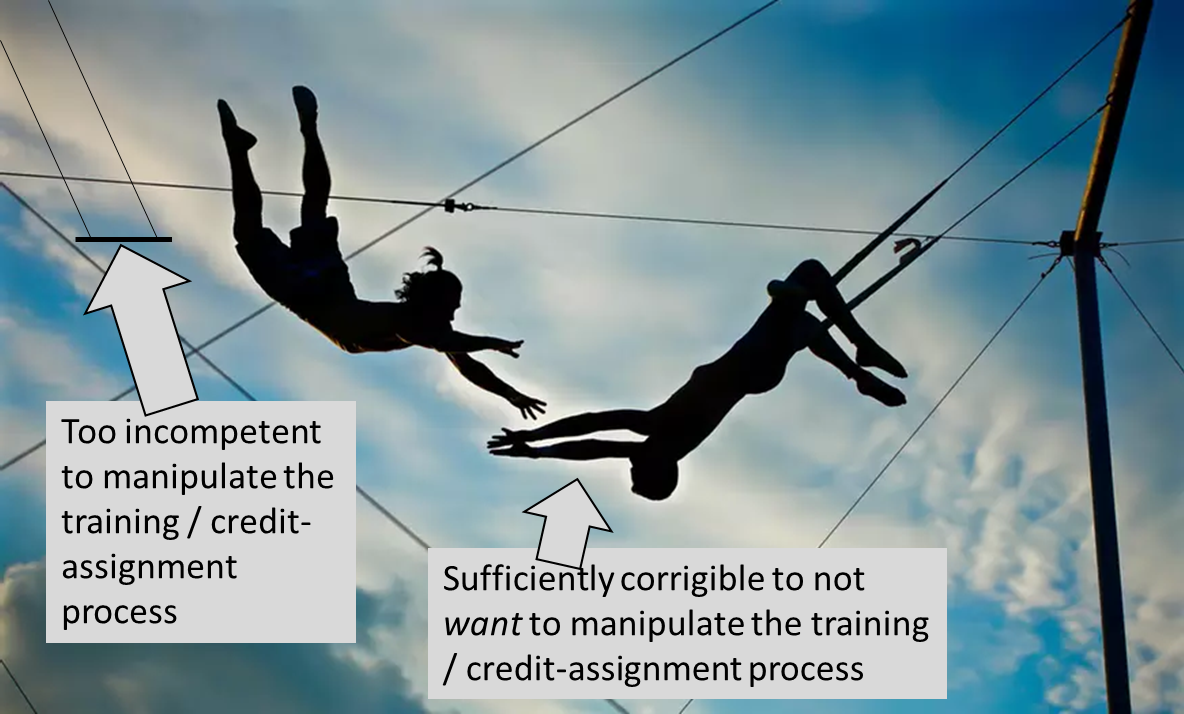

Unfortunately, as we saw in §10.3.2 above, “prevent my goals from changing” is one of those convergent instrumental subgoals that arises for many different motivations, with the notable exception of corrigible motivations (§10.3.3.2 above). Thus, it seems that we need to navigate a terrifying handoff between two different safety stories:

Early in training, the AGI does not have corrigible motivation (indeed the motivation starts out random!), but it’s too incompetent to manipulate its own training and credit assignment process to prevent goal changes.

Later in training, the AGI hopefully does have corrigible motivation, such that it understands and endorses the process by which its goals are being updated. Therefore it does not manipulate the motivation-updating process, even though it’s now smart enough that it could. (Or if it does manipulate that process, it does so in a way that we humans would endorse.)

(I am deliberately omitting a third alternative, “make it impossible for even a highly-intelligent-and-motivated AGI to manipulate its motivation-updating process”. That would be lovely, but it doesn’t seem realistic to me.)

10.6 Problems with the outer vs inner breakdown

10.6.1 Wireheading vs inner alignment: The Catch-22

In the previous post, I mentioned the following dilemma:

If the Thought Assessors converge to 100% accuracy in predicting the reward that will eventually result from a plan, then a plan to wirehead (hack into the Steering Subsystem and set valence to infinity) would seem very appealing, and the agent would do it.

If the Thought Assessors don’t converge to 100% accuracy in predicting the reward that will eventually result from a plan, then that’s the very definition of inner misalignment!

I think the best way to think through this dilemma is to step outside the inner-alignment versus outer-alignment dichotomy.

At any given time, the learned value function (valence Thought Assessor) is encoding some function that estimates which plans are good or bad.

A credit-assignment update is good if it makes this estimate align more with the designer’s intention, and bad if it makes this estimate align less with the designer’s intention.

The thought “I will secretly hack into my own Steering Subsystem” is almost certainly not aligned with the designer’s intention. So a credit-assignment update that assigns more positive value to “I will secretly hack into my own Steering Subsystem” is a bad update. We don’t want it. Does it increase “inner alignment”? I think we have to say “yes it does”, because it leads to better predictions! But I don’t care. I still don’t want it. It’s bad bad bad. We need to figure out how to prevent that particular credit-assignment Thought Assessor update from happening.

10.6.2 General discussion

I think there’s a broader lesson here. I think “outer alignment versus inner alignment” is an excellent starting point for thinking about the alignment problem. But that doesn’t mean we should expect one solution to outer alignment, and a different unrelated solution to inner alignment. Some things—particularly interpretability—cut through both outer and inner layers, creating a direct bridge from the designer’s intentions to the AGI’s goals. We should be eagerly searching for things like that.

Changelog

July 2024: Since the initial version, I’ve made only minor changes, including wording changes (e.g. I’m now using the word “valence” more), and updating the diagrams in line with other posts.

April 2025: I added a sentence near the top with an FYI that there’s some near-synonymous terminology in use: (“outer misalignment”, “inner misalignment”) ≈ (“specification gaming”, “goal misgeneralization”) respectively. I also added a new §10.2.3 discussing “behaviorist” versus “non-behaviorist” reward functions.

July 2025: I replaced a link in §10.2.3 with a later-and-better discussion of the same topic: Self-dialogue: Do behaviorist rewards make scheming AGIs? → “Behaviorist” RL reward functions lead to scheming.

January 2026: Created §10.1.1 (but most of its text was previously present as a footnote). Changed title from “The alignment problem” to “The technical alignment problem”. Added a new subsection to §10.3.1 about whether LLMs solved Goodhart’s law, and a new subsection to §10.3.3 about “the usual agent debugging loop” for solving Goodhart’s law today (with some text copied from this post). Rewrote §10.3.2.3 to explain consequentialist preferences and the surrounding debates. And many other smaller edits and updates throughout.

- ^

For example, by my definitions, “safety without alignment” would include AGI boxing, and “alignment without safety” would include the “fusion power generator scenario”. More in the next post.

- ^

Note that “the designer’s intention” may be vague or even incoherent. I won’t say much about that possibility in this series, but it’s a serious issue that leads to all sorts of gnarly problems.

- ^

One of the rare non-behaviorist rewards used in the mainstream RL literature today is “curiosity” / “novelty” rewards. For a nice historical discussion, I recommend The Alignment Problem by Brian Christian, chapter 6.

- ^

One could train an AGI to “tell me the right answer” on questions where I know the right answer, and hope that it generalizes to “tell me the right answer” on questions where I don’t. That might work, but it also might generalize to “tell me the answer which I will think is right”. See “Eliciting Latent Knowledge” for much more on this still-unsolved problem (here and follow-up).

- ^

For one thing, if two AGIs are in zero-sum competition, that doesn’t mean that neither will be able to hack into the other. Remember continual learning (§8.2.2) and brainstorming: One copy might have a good idea about how to hack into the other copy during the course of the debate, for example. The offense-defense balance is unclear. For another thing, they could both be jointly motivated to hack into the judge, such that then they can both get rewards! And finally, thanks to the inner alignment problem, just because they are rewarded for winning the debate doesn’t mean that they’re “trying” to win the debate. They could be “trying” to do anything whatsoever! And in that case, again, it’s no longer a zero-sum competition; presumably both copies of the AGI would want the same thing and could collaborate to get it. See also: Why I’m not working on {debate, RRM, ELK, natural abstractions}.

- ^

For my own quick take on why I don’t think CIRL is directly helpful for AGI extinction risk, see this 2025 comment.

- “Sharp Left Turn” discourse: An opinionated review by (28 Jan 2025 18:47 UTC; 220 points)

- [Intro to brain-like-AGI safety] 1. What’s the problem & Why work on it now? by (26 Jan 2022 15:23 UTC; 164 points)

- LeCun’s “A Path Towards Autonomous Machine Intelligence” has an unsolved technical alignment problem by (8 May 2023 19:35 UTC; 141 points)

- My AGI safety research—2025 review, ’26 plans by (11 Dec 2025 17:05 UTC; 133 points)

- “The Era of Experience” has an unsolved technical alignment problem by (24 Apr 2025 13:57 UTC; 115 points)

- [Intro to brain-like-AGI safety] 3. Two subsystems: Learning & Steering by (9 Feb 2022 13:09 UTC; 106 points)

- [Intro to brain-like-AGI safety] 15. Conclusion: Open problems, how to help, AMA by (17 May 2022 15:11 UTC; 100 points)

- Reward Function Design: a starter pack by (8 Dec 2025 19:15 UTC; 80 points)

- Response to Blake Richards: AGI, generality, alignment, & loss functions by (12 Jul 2022 13:56 UTC; 62 points)

- [Intro to brain-like-AGI safety] 8. Takeaways from neuro 1/2: On AGI development by (16 Mar 2022 13:59 UTC; 61 points)

- New version of “Intro to Brain-Like-AGI Safety” by (23 Jan 2026 16:21 UTC; 58 points)

- Re SMTM: negative feedback on negative feedback by (14 May 2025 19:50 UTC; 57 points)

- [Intro to brain-like-AGI safety] 9. Takeaways from neuro 2/2: On AGI motivation by (23 Mar 2022 12:48 UTC; 56 points)

- Reward button alignment by (22 May 2025 17:36 UTC; 52 points)

- [Intro to brain-like-AGI safety] 14. Controlled AGI by (11 May 2022 13:17 UTC; 47 points)

- [Intro to brain-like-AGI safety] 12. Two paths forward: “Controlled AGI” and “Social-instinct AGI” by (20 Apr 2022 12:58 UTC; 47 points)

- 's comment on AGI Ruin: A List of Lethalities by (7 Jun 2022 3:53 UTC; 39 points)

- [Intro to brain-like-AGI safety] 11. Safety ≠ alignment (but they’re close!) by (6 Apr 2022 13:39 UTC; 36 points)

- An AI-in-a-box success model by (11 Apr 2022 22:28 UTC; 16 points)

- “Intro to brain-like-AGI safety” series—just finished! by (EA Forum; 17 May 2022 15:35 UTC; 15 points)

- 's comment on Steve Byrnes’s Shortform by (3 Apr 2025 3:55 UTC; 15 points)

- 's comment on Reward button alignment by (23 May 2025 15:34 UTC; 14 points)

- New version of “Intro to Brain-Like-AGI Safety” by (EA Forum; 23 Jan 2026 16:21 UTC; 6 points)

- 's comment on Biomimetic alignment: Alignment between animal genes and animal brains as a model for alignment between humans and AI systems. by (EA Forum; 30 May 2023 18:24 UTC; 2 points)

- 's comment on “The Era of Experience” has an unsolved technical alignment problem by (24 Apr 2025 17:39 UTC; 2 points)

My take on the catch-22 on wireheading vs inner-alignment point is that I favor inner-aligning AIs to the reward function and take the low risk of wireheading than allowing inner misalignment to undo all our work.

My basic reasons for choosing the wirehead option over the inner-alignment option are based on my following views:

I think translation of our intent to machines without Goodharting too much is IMO likely reasonably easy to do by default, and this broadly is due to both being more willing to assume alignment generalizes from easy to hard cases than other people on LW, and the method used is essentially creating large datasets that do encode human values, which turns out to work surprisingly well for reasons that somewhat generalize to the harder cases:

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/oJQnRDbgSS8i6DwNu/the-hopium-wars-the-agi-entente-delusion#8gjhsKwq6qQ3zmXeq

https://www.beren.io/2024-05-15-Alignment-Likely-Generalizes-Further-Than-Capabilities/

As a corollary of this, this also means that we can create robust reward functions out of that dataset that prevent a lot of common reward hacking strategies, and so long as the values were trained in early such that it internalized it’s values before it’s superhumanly capable at everything means we can let instrumental convergence do the rest of the work for us.

The main principle here is to put alignment data before or during capabilities data, not after. This is why RLHF and a whole lot of other post-training methods for alignment are so bad.

We really shouldn’t screw up our outer alignment success by then introducing a inner-misaligned agent inside our AI.

Thankfully, I now see a clear answer to the question of whether we should promote wireheading over inner misalignment, and the choice is to wirehead a robustly good reward function than it is to get into the ocean of inner misalignment.

Yeah, there definitely seems to be something off about that categorization. I’ve thought a bit about how this stuff works in humans, particularly in this post of my moral anti-realism sequence. To give some quotes from that:

So, it seems like we don’t want “perfect inner alignment,” at least not if inner alignment is about accurately predicting reward and then forming the plan of doing what gives you most reward. Also, there’s a concept of “lock in” or “identifying more with the long-term planning part of your brain than with the underlying needs-meeting machinery.” Lock in can be dangerous (if you lock in something that isn’t automatically corrigible), but it might also be dangerous not to lock in anything (because this means you don’t know what other goals form later on).

Idk, the whole thing seems to me like brewing a potion in Harry Potter, except that you don’t have a recipe book and there’s luck involved, too. “Outer alignment,” a minimally sufficient degree thereof (as in: the agent tends to gets rewards when it takes actions towards the intended goal), increases the likelihood that you get broadly pointed you in the right direction, so the intended goal maybe gets considered among things the internal planner considers reinforcing itself around / orienting itself towards. But then, whether the intended gets picked over other alternatives (instrumental requirements for general intelligence, or alien motivations the AI might initially have), who knows. Like with raising a child, sometimes they turn out the way the parents intend, sometimes not at all. There’s probably a science to finding out how outcomes become more likely, but even if we could do that with human children developing into adults with fixed identities, there’s then still the question of how to find analogous patterns in (brain-like) AI. Tough job.

I read that sequence a couple months ago (in preparation for writing §2.7 here), and found it helpful, thanks.

I agree that we’re probably on basically the same page.

FYI Alex also has this post making a similar point.

I think I agree, in that I’m somewhat pessimistic about plans wherein we want the “adult AI” to have object-level goal X, and so we find a reward function and training environment where that winds up happening.

Not that such a plan would definitely fail (e.g. lots of human adults are trying to take care of their children), just that it doesn’t seem like the kind of approach that passes the higher bar of having a strong reason to expect success (e.g. lots of human adults are not trying to take care of their children). (See here for someone trying to flesh out this kind of approach.)

So anyway, my take right now is basically:

If we want the “adult AGI” to be trying to do a particular thing (‘make nanobots’, or ‘be helpful towards its supervisor’, or whatever), we should replace (or at least supplement) a well-chosen reward function with a more interpretability-based approach; for example, see Plan for mediocre alignment of brain-like [model-based RL] AGI (which is a simplified version of Post 14 of this series)

Or we can have a similar relation to AGIs that we have to the next generation of humans: We don’t know exactly at the object level what they will be trying to do and why, but they basically have “good hearts” and so we trust their judgment.

These two bullet points correspond to the “two paths forward” of Post 12 of this series.

But what exactly are new ideas? It could be the case that intelligence is pattern-matching at it most granural level even for “noveties”. What could come in handy here is a great flagging mechanism for understanding when the model is out-of-distribution. However, this could come at its own cost.

Is the use of “deliberately” here trying to account for the *thinking about its own thoughts*-part of going back and forth between thought generator and thought assesor?

I mean “new ideas” in the everyday human sense. “What if I make a stethoscope with an integrated laser vibrometer?” “What if I try to overthrow the US government using mind control beams?” I agree that, given that these are thinkable thoughts, they must be built out of bits and pieces of existing thoughts and ideas (using analogies, compositionality, etc.).

And then the value function will mechanically assign a value more-or-less based on the preexisting value of those bits and pieces. And my claim is that the result may not be in accordance with what we would have wanted.

Yeah, more on that topic in §14.4. :-)

Yes to “thinking about its own thoughts”, no to “going back and forth between thought generator and thought assessor”.

Instead I would say, you can think about lots of things, like football and calculus and sleeping. Another thing you can think about is your own preferences. When you think about football or calculus or sleeping, it’s an activation pattern within your thought generator, and the Thought Assessors will assess it (positive valence vs negative valence, does or doesn’t warrant cortisol release etc.). By the same token, when you think about your own preferences, the Thought Assessors will assess that thought as positive-valence vs negative-valence etc. So you can have preferences about your own (current and/or future) preferences, a.k.a. meta-preferences. And you can make plans that will result in you having certain preferences, and those plans are likely to be appealing if they align with your meta-preferences.

So if I think that reading nihilist philosophy books might lead to me no longer caring about the welfare of my children, I will feel some motivation not to read nihilist philosophy books. By the same token, if the AGI wants to like or dislike something, I think there’s a reasonable chance that it will find a way to make that happen.

>See “Eliciting Learned Knowledge” for much more on this still-unsolved problem

I think it should be “Latent”.

Fixed it, thanks.