Related: The case for logical fallacies

Julia Galef makes an interesting point in her recent book The Scout Mindset: our beliefs come as tangled knots, not isolated strings. Changing one belief often implies that we change many others.

Consider Sarah, whose relationships, political beliefs, worldview, daily activities, and ethical code are all fundamentally derived from her religious beliefs. Sarah can’t merely decide that God doesn’t exist or that Hinduism is correct instead of Judaism or whatever; if taken to heart, such a change in worldview would imply reform of virtually every other aspect of her life: her belief that abortion is intrinsically immoral, her belief that contributing significant time and money to her congregation is an ethical and meaningful thing to do, and her belief that it is good and appropriate to go to Synagogue every Friday, among countless others

If Sarah wishes to maintain a harmonious, coherent set of practices, beliefs, and attitudes, it would take a tremendous amount to convince her that God isn’t real—crucially, more than if this belief were siloed away from the rest of her life and mind.

This isn’t an indictment of religion. It would take an equally huge amount of evidence to convince me that I should convert to orthodox Judaism—more than if my non-religiosity was siloed away from my other beliefs and behaviors.

The key clause, though, is “if Sarah wishes to maintain a harmonious, coherent set of practices, beliefs, and attitudes.” Why should Sarah wish to do so? Why should anyone?

The case against hypocrisy

Before making the case for hypocrisy, let me explain why, in many respects, hypocrisy is bad and maintaining a consistent set of practices and beliefs is good. I’m not just steelmanning to strengthen my later argument; hypocrisy often really is something to be avoided. The word has several definitions, but I’ll use Merriam-Webster’s

Definition of hypocrisy

1. a feigning to be what one is not or to believe what one does not : behavior that contradicts what one claims to believe or feel

Also, much of the rest of this post will apply to plain old inconsistency, or holding two or more contradictory beliefs.

In general, from a non-religious perspective, our beliefs do not intrinsically matter (to others, that is; they may directly impact our own conscious experience). Our actions do. It doesn’t matter whether you believe that animal suffering is bad, or that Trump is awesome, or that we should end homelessness. It matters whether you act on those beliefs, perhaps by foregoing factory farmed animal products, voting and donating to the Trump 2024: Make America as Great as it was From 2016-2020 campaign, or becoming a YIMBY activist in your city.

The thing with action is that sometimes it’s hard. Chicken nuggets taste good. Voting can be a hassle. Getting rid of single family zoning might decrease your property value.

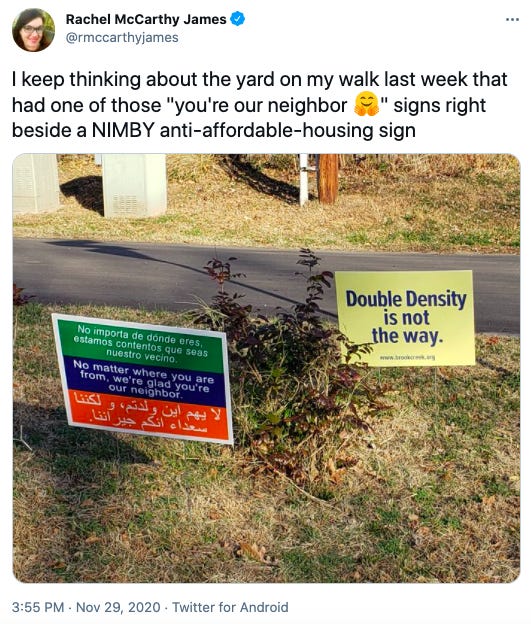

Our natural, moral distaste for hypocrisy is a decent solution. We get outraged when someone who professes to believe X does or believes something in that seems to conflict with X. That’s why Tweets like this one are so delicious.

To a large extent, this is a force for good! Lots of people are well-intentioned and want to believe true, good things, and many succeed in doing so. Our aversion to hypocrisy is a clever socio-psychological mechanism to turn good beliefs into good deeds. The process might look something like this:

John becomes convinced that buying factory farmed eggs is bad.

He keeps buying factory farmed eggs out of habit and behavioral inertia.

He feels bad about being a hypocrite or becomes worried that others will see him as a hypocrite.

John stops buying factory farmed eggs.

Cool. Now, for the contrarian take.

The case for hypocrisy

One man’s modus ponens is another man’s modus tollens.

- Confucius (just kidding, I don’t know who said it first)

Our aversion to hypocrisy can also have the opposite effect. For example…

John becomes convinced that buying factory farmed eggs is bad.

He keeps buying factory farmed eggs out of habit and behavioral inertia.

He feels bad about being a hypocrite or becomes worried that others will see him as a hypocrite.

John decides that buying factory farmed eggs actually isn’t bad, or just tries to forget about it (and this need not come from conscious deliberation).

Ok, you might ask, why is hypocrisy the problem here? If John didn’t feel bad about being (seen as) a hypocrite, wouldn’t he have kept buying factory farmed eggs anyway? Maybe. He certainly would have found it easier to continue buying the eggs while holding the intellectual belief that doing so is wrong.

But aversion to hypocrisy isn’t the only reason people do things.

Even if John doesn’t care one iota about his hypocrisy per se, he might eventually decide to stop buying the eggs for some other reason in the same way he might donate to the Humane League since doing so isn’t in direct contradiction with the belief “buying factory farmed eggs is fine.”

Maybe he doesn’t give up eggs but does start making an offsetting donation to effective animal welfare charities. Maybe he starts buying humane-certified eggs most of the time. Whatever you think about their moral worthiness, these alternatives might be available to John in a way that egg abstinence is not

Identity

This is particularly likely if John’s egg consumption is tangled up with other beliefs and identities.

For instance, say John is a die-hard keto bro who thinks Big Vegan is conspiring with the seed oil industry, Big Pharma, and the FDA to push inflammatory and insulin-spiking fruits, grains, and unsaturated fats on the American people, and understands his egg consumption as a vote against this industrial complex.

Ok, fine. If John’s ultimate goal in life is to avoid hypocrisy but he is unwilling to forego the eggs, he’ll do whatever it takes to avoid the conclusion that buying factory farmed eggs is wrong. And if he does this, he’ll never have a reason to explore alternatives like making an offsetting donation or spending a bit to purchase a more ethical brand.

Now, let’s say John has a bit more tolerance for his own hypocrisy. Or, to use a less-loaded word, “compartmentalization.” For a while, John recognizes that factory farmed eggs are bad but keeps buying them anyway. Without the need to immediately resolve this apparent conflict, John’s modus tollens turns into something almost like modus pollens:

In less pretentious academic terms, ‘Compartmentalization is ok’ John’s reasoning goes like this:

It still might be wrong to buy factory farmed eggs, even if I do keep buying them (‘not Q’ does not imply ‘not P’).

My identity is wrapped up in egg consumption, so I will keep buying eggs (not Q).

Ok, factory farmed eggs are still bad. (P)

If I accept (2) and (3), what should I do about it? Maybe donate to THL and try to find a more ethical brand when I can.

and Anti-hypocrisy John’s reasoning goes like this:

If it is wrong to buy factory farmed eggs, I won’t buy them (if P then Q).

My identity is wrapped up in egg consumption, so I will keep buying eggs (not Q).

Therefore it can’t be wrong to buy factory farmed eggs (not Q, therefore not P).

What’s going on here?

Strictly speaking, Anti-hypocrisy John could logically and coherently donate money or do something similar just like is ‘Compartmentalization is ok’ alter ego. But, in the real world, my claim is that an aversion to hypocrisy/inconsistency often leads to a hasty rejection (likely not after conscious deliberation) of whichever of the two conflicting actions or beliefs is easier for one to reject.

For John, that means forgetting about or ignoring the ethics of egg consumption before he even has time to ponder whether there might be a decent-but-imperfect way of sorta reconciling his conflicting beliefs and actions

Two wrongs don’t make a right

A hyper-simplified illustration:

Jane believes bad thing 1 and bad thing 2, which are perfectly consistent.

Tim believes bad thing 1 and good thing 2, which are contradictory and render him a hypocrite.

Which person would you rather be? Well, I’d rather be Tim. Intellectual consistency is not the highest value, and I’d rather be half right than entirely, consistently wrong. If Tim decides that hypocrisy must be avoided at all costs, he has two choices:

Believe bad thing 1 and bad thing 2

Believe good thing 1 and good thing 2.

As an empirical matter, which option Time goes with probably depends on whether he is more personally invested in question 1 or question 2. But Tim doesn’t know which beliefs and actions are ‘good.’ No one says to themselves “sucks that I believe things that are immoral and false, but at least I’m not a hypocrite.”

Instead, an aversion to hypocrisy serves as a potent motivation for coming to the conclusion that one’s preferred action or belief is in fact true or good. Sometimes this will happen to be correct, but often it will not. Permitting hypocrisy gives us some breathing room to make the decision.

Conclusion

I’m not making the claim that we should ignore or unequivocally embrace hypocrisy. However, tolerance for inconsistency can better allow people to gradually change their behaviors and beliefs without facing the near-impossible task of wholesale behavioral or ideological reform.

Ultimately, I think that tolerating hypocrisy is generally wise when the “worse” of two conflicting beliefs is more closely held or linked with a person’s identity. Our tangled knot of beliefs is only tangled insofar as hypocrisy must be avoided, and sometimes taking a knife to the rope is the only way to improve the knot.

The OP, as well as the other hypocrisy-favorable posts linked by Abram here in the comments, seem to do a poor job IMO at describing why anti-hypocrisy norms could be important. Edit: Or, actually, it seems like they argue in favor for a slightly different concept, not what I’d call “hypocrisy.”

I like the definition given in the OP:

The OP then describes a case where someone thinks “behavior x is bad,” but engages in x anyway. Note that, according to the definition given, this isn’t necessarily hypocrisy! It only constitutes hypocrisy if you implicitly or explicitly lead others to believe that you never (or only very infrequently) do the bad thing yourself. If you engage in moral advocacy in an honest, humble or even self-deprecating way, there’s no hypocrisy.

One might argue (e.g., Katja’s argument) that it’s inefficient to do moral advocacy without hypocrisy. That seems like dubious naive-consequentialist reasoning. Besides, I’m not sure it’s empirically correct. (Again, I might be going off a subtly different definition of “hypocrisy.”) I find arguments the most convincing when the person who makes them seems honest and relatable. There are probably target audiences to whom this doesn’t apply, but how important are those target audiences (e.g., they may also not be receptive to rational arguments)? I don’t see what there’s to lose by not falsely pretending to be a saint. The people who reject your ideas because you’re not perfect, they were going to reject your ideas anyway! That was never their true rejection – they are probably just morally apathetic / checked out. Or trolls.

The way I see it, hypocrisy is an attempt to get social credit via self-deception or deceiving others. All else equal, that seems clearly bad.

I’d say that the worst types of people are almost always extreme hypocrites. And they really can’t seem to help it. Whether it’s deceit of others or extreme self-deception, seeing this stuff in others is a red flag. I feel like it muddles the waters if you start to argue that hypocrisy is often okay.

I don’t disagree with the view in the OP, but I don’t like the framing. It argues not in favor of the hypocrisy as it’s defined, but something in the vicinity.

I feel like the framing of these “pro-hypocrisy” arguments should rather be “It’s okay to not always live up to your ideals, but also you should be honest about it.” Actual hypocrisy is bad, but it’s also bad to punish people for admitting imperfections. Perversely, by punishing people for not being moral saints, one incentivizes the bad type of hypocrisy.

tl;dr hypocrisy is bad, fight me.

(As you may notice, I do have a strong moral distaste for hypocrisy.)

See also my argument against anti-hypocricy norms, Rob’s argument against hypocrisy as an argument against anything, Katja’s pro-hypocrisy argument, and this 2014 post by the_duck.

Looks like I’m in good company!

I opened this article with intention to argue against your point (without knowing what it will be).

It showed to me how highly I value consistency and despise hypocrisy. And I realize now how it can make it more difficult for me to change my beliefs.

So, thank you for this. I’ll try to keep it in my mind.

I think people are already tolerant of the level of hypocrisy that can be useful. For example, a new convert to Islam will have more slack in doing unislamic things.

Anyhow, this is not an isolated matter. Any kind of punishment has the potential to create adverse effects; Banning ransom payments can cause secret ransom payments, banning drugs powers gangs, banning one carcinogenic chemical can make companies use an even worse carcinogenic chemical, … . There is no general solution to these, but I’m inherently skeptical of claims that favor the status quo of “rabbits” in a rabbit-stag game.

I think of modularity/composability of beliefs like lego. It is important for pieces to be able to be different so they serve different tasks, yet also important for them to maintain certain properties so that they remain connectable to other lego. Pieces that conform along more dimensions will be more composable and thus more usable in many different ways (more generic pieces) while pieces that conform along fewer dimensions can accomplish more specialized tasks but also create limits on how well they interface with other pieces (super specialized pieces that ‘are only good for their specific purpose’ in specialty sets.)

Can you provide concrete examples of the specialized pieces?

Detailed maps of technical or personal subjects. Like knowing particular idiosyncracies of your job or relationships.

There are a bunch of issues where I disagree with something. And I could take some meaningless action like many of the ones mentioned, like not buying something in order to protest, but it won’t matter.

Similarly I could spend my whole income to help 1 homeless person or warren Buffett could donate his whole fortune to fix income inequality. But it doesn’t make us hipocrites if we don’t do this action : a real fix for these problems requires a rule change. A federal law to force higher housing densities, a wealth tax on all billionaires not just buffet.

What do you mean by ‘real fix’ here? What if said that real-real fix requires changing human nature and materialization of food and other goods out of nowhere? That might be more effective fix, but it is unlikely to happen in near future and it is unclear how you can make it happen. Donating money now might be less effective, but it is somehow that you can actually do.

A real fix is forcing everyone in a large area to contribute to fixing a problem. If enough people can’t be compelled to contribute the problem can’t be fixed. Doing something that costs you resources but doesn’t fix the problem and negatively affects you vs others who aren’t contributing but are competing with you isn’t a viable option.

In prisoners dilemma you may preach always cooperate but you have to defect if your counterparty won’t play fair. Similarly warren Buffett can preach that billionaires should pay more taxes but not pay any extra voluntarily until all billionaires have to.

But that’s a fix to a global problem that you won’t fix anyway. What you can do is allocate some resources to fixing a lesser problem “this guy had nothing to eat today”.

It seems to me that your argument proves too much—when faced with a problem that you can fix you can always say “it is a part of a bigger problem that I can’t fix” and do nothing.