Beware unfinished bridges

This guy don’t wanna battle, he’s shook

’Cause ain’t no such things as halfway crooks- 8 Mile

There is a commonly cited typology of cyclists where cyclists are divided into four groups:

Strong & Fearless (will ride in car lanes)

Enthused & Confident (will ride in unprotected bike lanes)

Interested but Concerned (will ride in protected bike lanes)

No Way No How (will only ride in paths away from cars)

I came across this typology because I’ve been learning about urban design recently, and it’s got me thinking. There’s all sorts of push amongst urban designers for adding more and more bike lanes. But is doing so a good idea?

Maybe. There are a lot factors to consider. But I think that a very important thing to keep in mind are thresholds.

It will take me some time to explain what I mean by that. Let me begin with a concrete example.

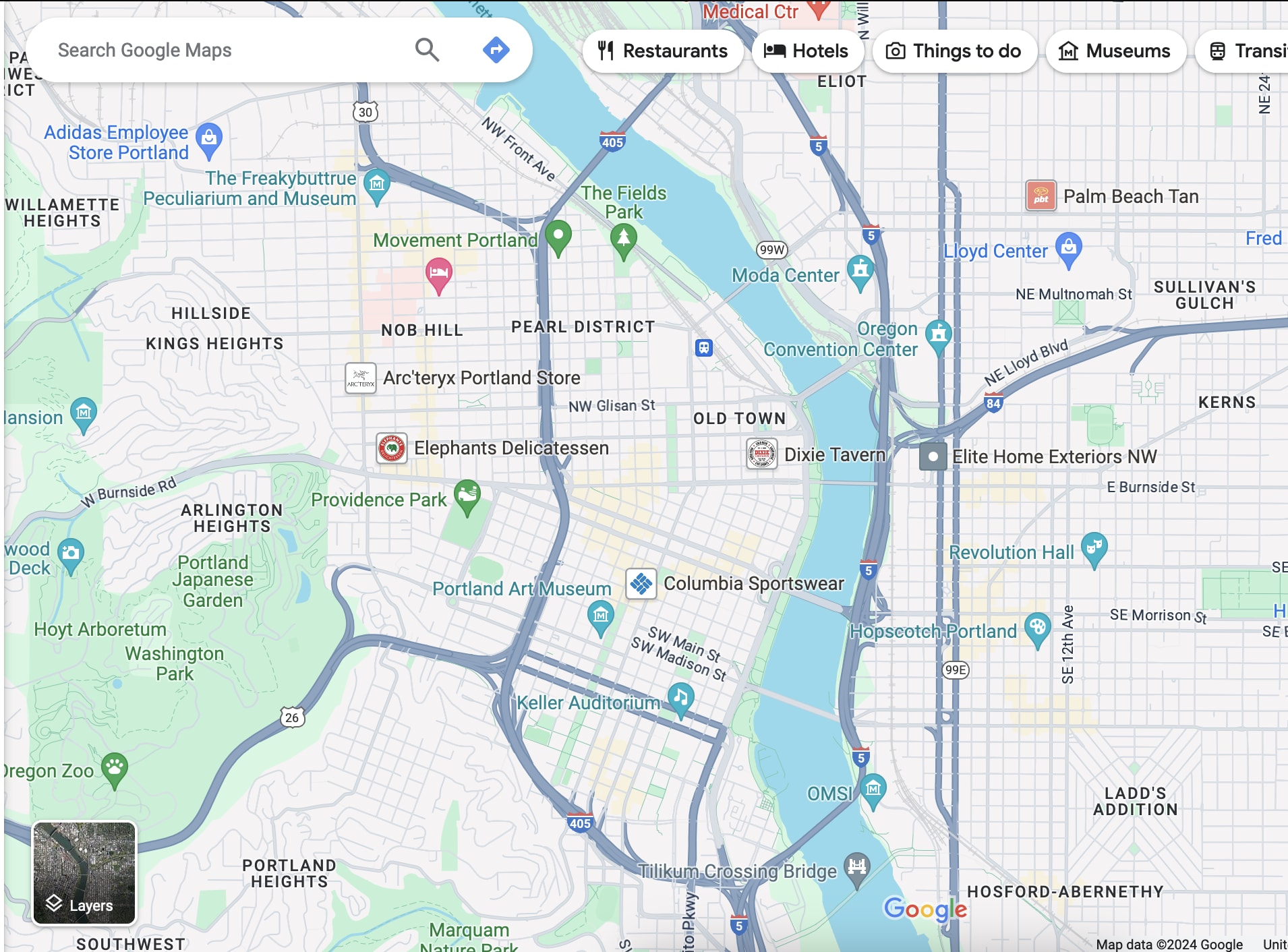

I live in northwest Portland. There is a beautiful, protected bike lane alongside Naito Parkway that is pretty close to my apartment.

It basically runs along the west side of the Willamette River.

Which is pretty awesome. I think of it as a “bike highway”.

But I have a problem: like the majority of people, I fall into the “Interested but Concerned” group and am only comfortable riding my bike in protected bike lanes. However, there aren’t any protected bike lanes that will get me from my apartment to Naito Parkway. And there often aren’t any protected bike lanes that will get me from Naito Parkway to my end destination.

In practice I am somewhat flexible and will find ways to get to and from Naito Parkway (sidewalk, riding in the street, streetcar, bus), but for the sake of argument, let’s just assume that there is no flexibility. Let’s assume that as a type III “Interested but Concerned” bicyclist I have zero willingness to be flexible. During a bike trip, I will not mix modes of transportation, and I will never ride my bike in a car lane or in an unprotected bike lane. With this assumption, the beautiful bike lane alongside Naito Parkway provides me with zero value.[1]

Why zero? Isn’t that a bit extreme? Shouldn’t we avoid black and white thinking? Surely it provides some value, right? No, no, and no.

In our hypothetical situation where I am inflexible, the Naito Parkway bike lane provides me with zero value.

I don’t have a way of biking from my apartment to Naito Parkway.

I don’t have a way of biking from Naito Parkway to most of my destinations.

If I don’t have a way to get to or from Naito Parkway, I will never actually use it. And if I’m never actually using it, it’s never providing me with any value.

Let’s take this even further. Suppose I start off at point A, Naito Parkway is point E, and my destination is point G. Suppose you built a protected bike lane that got me from point A to point B. In that scenario, the beautiful bike lane alongside Naito Parkway would still provide me with zero value.

Why? I still have no way of accessing it. I can now get from point A to point B, but I still can’t get from point B to point C, point C to point D, D to E, E to F, or F to G. I only receive value once I have a way of moving between each of the six sets of points:

A to B

B to C

C to D

D to E

E to F

F to G

There is a threshold.

If I can move between zero pairs of those points I receive zero value.

If I can move between one pair of those points I receive zero value.

If I can move between two pairs of those points I receive zero value.

If I can move between three pairs of those points I receive zero value.

If I can move between four pairs of those points I receive zero value.

If I can move between five pairs of those points I receive zero value.

If I can move between six pairs of those points I receive positive value.

I only receive positive value once that threshold is met.

Why does this matter? Well, say that you are the city of Portland and you are deciding whether to add an unprotected bike lane between points A and B. You have to ask yourself in what way you expect this new unprotected bike lane to add value for people.

If you just add that one bike lane and then stop, I don’t see the new bike lane getting many people past a threshold that would yield positive value for them. I think it’d function largely as an unfinished bridge.[2]

However, if the new bike lane is one step in a larger plan to build a complete bridge, so to speak, then that starts seeming to me like something that might be a good idea. The “larger plan” part is crucial though: you only get value once the bridge is complete, so if you’re going to start building a bridge, you better make sure you have plans to finish it.

Literal unfinished bridges provide negative value to all users, and stand as a monument to government incompetence, degrading the will to invest in future infrastructure.

Short bike lanes provide positive value to at least some users. They stand as a monument to the promise of a substantial, interconnected bike grid. They incrementally increase people’s propensity to bike. They push the city toward a new, bike-friendly equilibrium. The same is true for mass transit generally when the components that have been built work well. Portland ought to be thinking about its population-level utility over the long run, not your personal utility now.

As such, I think that “unfinished bridges” is a misleading metaphore for the S-curve phenomenon you are talking about, and “beware” is probably not the right take when it comes to the idea of incrementally moving along S-curves. In fact, when the S-curve is the payoff for incremental steps toward a desired goal, “take heart” seems more correct. Incremental moves along an S-curve bring you closer to saturation faster than it would seem, judging by linear extrapolation of the marginal gains of each incremental step. I added labels to Tiuto’s plot that reflect this change in interpretation.

Edit: There are multiple reasons all the incremental steps toward saturation of the S-curve aren’t always taken at once. In the case of bike lanes, availability of funds, land, and political will are sporadic. Incremental opportunities must be seized where possible over the course of years or decades. In other cases, there may be uncertainty in how to design the buildout to maximize the level of saturation that becomes incrementally resolved over time, such as a startup that’s trying to find product/market fit or a politician who’s trying to determine what platform would maximize their vote share by gauging the public’s reaction to a sequence of political appearances.