[Valence series] 4. Valence & Social Status (deprecated)

~~

~~

UPDATE JUNE 2024: THIS POST IS DEPRECATED!!

THE NEW VERSION IS: Valence & Liking / Admiring

~~

~~

4.1 Post summary / Table of contents

Part of the Valence series.

(UPDATE JAN 2024: I think this post has some issues, and is at best just a small piece of the social status puzzle. I am now working on a new and hopefully-much-better longer post on social status phenomena in general.)

The previous three posts built a foundation about what valence is, and how it relates to thought in general. This post will now discuss how valence sheds light on the social world specifically, with a particular emphasis on social status.

Section 4.2 presents my main thesis for this post: The core of social status involves a situation where Person X has beliefs about the valence felt by (a generic) Person Y when they think about Person Z. If this valence tends to be positive, then X will describe the situation by saying that Z has high status.

Section 4.3 mentions “dual strategies theory”—the idea that prestige and dominance are two different social rankings. I am using “status” to mean specifically “prestige”, not “dominance”.

Section 4.4 discusses our tendency to “mirror” people whom we respect, in their careers, beliefs, and so on.

Section 4.5 proposes that we have an “innate status drive”, and speculates on how it works.

Section 4.6 discusses other possible valence-related social innate drives, most of which I remain pretty uncertain about.

Section 4.7 argues that my felt social status is different from my self-esteem, but that the former can have an outsized impact on the latter.

Section 4.8 is a brief conclusion.

4.2 Main thesis: The core of social status involves a situation where Person X has beliefs about the valence felt by (a generic) Person Y when they think about Person Z

That’s a bit of a mouthful, but let’s walk through it step by step.

Start with the simpler (albeit noncentral) case where Person X = Person Y in the section heading. Even more specifically, let’s say Person X = Person Y = me, and Person Z = Tom Hanks.

So, as our first example, suppose my brain tends to assign a positive valence to thoughts of Tom Hanks. I might say “Tom Hanks is really great” or “I like Tom Hanks” or “I have a lot of respect for Tom Hanks”. My brain would apply the Halo Effect to him (see §3.4.4) and I’m more inclined to give the benefit of the doubt to anything having to do with him (see §2.4.3).

Now, in this situation, I might say: “As far as I’m concerned, Tom Hanks has a high social status”, or “In my eyes, Tom Hanks has high social status.” This is an unusual use of the term “high social status”, but hopefully you can see the intuition that I’m pointing towards.

Next step: Suppose lots of people likewise assign positive valence to thoughts of Tom Hanks, including pretty much everyone who knows him, or knows of him, or interacts with him. And suppose that this fact is common knowledge. Then I would just say: “Tom Hanks has high social status”, without any caveats.

What about more complicated cases? Suppose most Democrats find thoughts of Barack Obama to be positive-valence, but simultaneously most Republicans find thoughts of him to be negative-valence, and this is all common knowledge. Then I might sum that up by saying “Barack Obama has high status among Democrats, but Republicans view him as pond scum”.

4.3 Terminological note: I’m using “status” to mean prestige, not dominance

In “dual strategies theory” (see Elephant in the Brain for a friendly introduction), there are two kinds of “status”, namely prestige and dominance. These correspond roughly to being “widely-respected” and “widely-feared” respectively.

I’m adopting a different terminology, where the word “status” is a synonym of “prestige” specifically. This seems to be how the word “status” is almost always used in practice, at least in my own social circles.

If I want to talk about dominance, I’ll just use the word “dominance”. If I want to talk about dominance and prestige lumped together, I guess I’ll say “dominance and prestige”, but I find that this combination rarely comes up in conversation anyway.

4.3.1 …But still, what about dominance?

Going back to the prestige-versus-dominance split of §4.3 above, I claim the distinction is pretty straightforward:

If, when lots of people think of Person X, their brains tend to respond with positive valence, then that fact is related to X’s social status / prestige (as above);

If, when lots of people think of Person X, their brains tend to respond with fear of them (or awe, or something in that vicinity) then that fact is related to X’s dominance.

That’s all I have to say on the topic of dominance.

4.4 Our tendency to mimic people we respect, in their careers, preferences, clothes, beliefs, etc.

I think there’s a general tendency wherein, if Person X whom I respect (i.e. who elicits high valence in my mind) is doing Thing Y, then I’ll be tempted to do Y too.

To explain this fact, we don’t need any specific innate mechanisms beyond the general concepts that I’ve already discussed in this series. Instead, I think it’s just the same thing as the phenomenon of §2.5.1: if different concepts “go together”, then TD learning will tend to push their respective valences towards each other. Thus, if the thought of Person X tends to evoke highly positive valence, and I often think about how Person X is doing Thing Y, then the valence that my brain assigns to Thing Y is liable to go up as well. And then, naturally (§2.4.3), I’m going to want to do Thing Y myself (or at least, I’ll think it’s a good thing to do in general, even if it’s not really a good fit for me personally).

More generally, if people you respect (assign high valence to) tend to have certain careers, clothes, personality traits, slang, beliefs, etc., then your brain is going to start assigning high valence to all those things, and thus also assign higher valence to any other people associated with those things, and also higher valence to the idea of getting those things for ourselves. (And we might say that those clothes, beliefs, etc. are high-status clothes, high-status beliefs, etc., at least in our eyes)

4.5 Innate status drive

4.5.1 I think status-seeking is an innate drive, not a learned strategy

For everything I’ve said so far in this post, there needn’t be anything special and specific in the brain underlying status per se. The same brain mechanisms that associate positive valence with the thought of a particular chair, can likewise associate positive valence with the thought of a particular person. And by the same token, we can have beliefs about how this mechanism is playing out in other people’s heads, again just like we can have beliefs about anything else that other people are thinking and feeling. No status-specific brain components are required for that.

But I do think there’s something special and specific that the genome builds into the brain for status drive, i.e. a reflex that says: if I believe that other people (especially other people I respect) find thoughts of me to be high valence, then that belief is itself intrinsically rewarding to me.

Stepping back a bit: As I’ve mentioned in §2.5 and discussed in much more detail elsewhere, I think there’s a sharp and important distinction between “innate drives” versus the various products of within-lifetime learning. One way to tell them apart is that, if something is not a human cross-cultural universal, then it’s unlikely to be directly related to an innate drive. But the converse is not true: If something is a cross-cultural universal, then maybe it’s directly related to an innate drive, or an alternative possibility is that everyone has similar learning algorithms, and everyone has similar life experience (in certain respects), so maybe everyone winds up adopting the same habits. Let’s call that alternative possibility “convergent learning”.

Applying this general idea to status-seeking behavior, I believe that this kind of behavior is empirically a cross-cultural human universal. So two hypotheses would be: it’s a direct innate drive, or alternatively, it’s “convergent learning”—each person learns from life experience that lots of good things happen when they have high status.

Anyway, my strong belief is that it’s the former—a direct innate drive, not “convergent learning”. That belief comes from various sources, including how early in life status-seeking starts, how reliable it is, the person-to-person variability in how much people care about their status, and the general inability of people to not care about status, even in situations where it has no other downstream consequences.

Here’s another piece of evidence, maybe: I think some high-functioning sociopaths are (in many but not all respects) examples of what it looks like for a person to operate in the social world via pure learned strategy rather than innate social drives. How does their status-seeking behavior compare to normal? My impression is: they are substantially more open-minded to forgoing social status than normal. In particular, there’s a strategy of “getting other people to pity me”. This strategy seems to be a good way to extract favors from people, and high-functioning sociopaths famously use this strategy way more than most people.[1] But this strategy seems to require a lack of status-seeking—being pitied is not exactly a high-status move! So maybe that’s another bit of evidence that status-seeking normally derives from an innate drive, not from within-lifetime learning of instrumentally-useful social strategies.

Incidentally, I find that, in the evolutionary psychology literature, there’s a widespread tendency to entirely ignore the possibility of “convergent learning”. So, I am in agreement with the mainstream that there’s an innate social status drive, but only because I think the mainstream got lucky.

4.5.2 How might an innate status drive work?

If I’m right, then how does that innate drive work? Neuroscientific details would be way out of scope (and I don’t know them anyway). But in broad strokes, I propose the following recipe:

If I think a thought …

…and the thought entails a different Person X thinking Thought which is about me…

…and if, in my thought , I imagine that Person X finds Thought to have [positive / negative] valence…

…then my brain assigns [positive / negative] valence to Thought .

The slightly-more-detailed version would involve a mechanism that enables my brainstem to detect and react to transient empathetic simulations. In a post last year, I surmised that most human social innate drives, from schadenfreude to compassion, involve that kind of mechanism. But I didn’t have any good examples at the time. Well, the above status drive recipe is my first good example! Or so I hope—I still need to flesh it out into a more detailed model, like with nuts-and-bolts pseudocode along with how it’s implemented in neuroanatomy. (And then proving that hypothesis experimentally would be far harder still.)

Two more details:

First, I think the above recipe is oversimplified, and that one of the missing ingredients is the valence that I assign to Person X. For example, as a public blogger, sometimes I learn that some random teenager somewhere knows who I am and thinks fondly of me. If so, that’s great, and I would feel happy about that. But suppose instead that I learn that Taylor Swift knows who I am and thinks fondly of me. Then that would feel way way more exciting to me! (I’m a big fan.) I think explaining this contrast requires an extra ingredient in the innate drive recipe above.

Second, there might be an adaptation mechanism—if you have a lot of status, then thoughts of other people respecting you gradually lose some or most of their positive valence. Instead you get positive valence for thoughts of other people respecting you more than the baseline expectation.

4.6 Other valence-related social innate drives?

This section is pretty speculative, but here are some thoughts:

Supposedly, status can contribute to sexual attraction. More specifically, the stereotype I’ve heard involves women being more attracted to high-status men, other things equal. I don’t know if that’s true, but if it is, I think it would have to be a specific innate mechanism installed into our brain by the genome. I don’t think it can be explained as an incidental side-effect of other stuff that I’ve talked about.

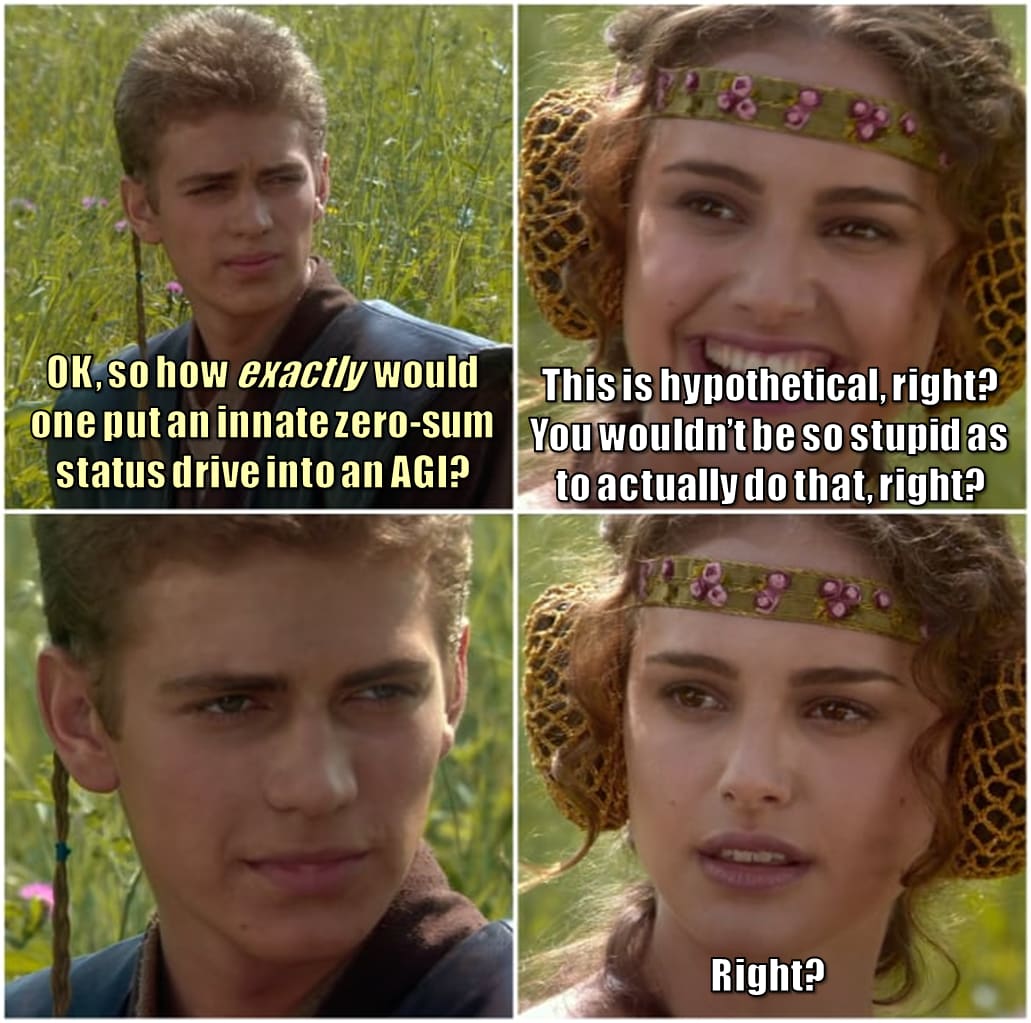

I think there’s something about status competition that I’m still missing. From an evolutionary perspective, status competition is no mystery—for example, insofar as mating opportunities is a zero-sum game, a person should care about whether their status is higher or lower than other people’s, not just whether they are viewed positively or negatively on an absolute scale. But from a mechanistic perspective, what I wrote in §4.5.2 seems inadequate to explain status competition. For example, according to the §4.5.2 story, it seems perfectly possible for there to be an omni-prestigious society, wherein everybody thinks that everybody is great (i.e., everyone assigns positive valence to everyone), and everybody is happy about that. Right? But that doesn’t seem to happen—maybe some Buddhist monks have great respect for everybody, but normal people don’t. Here are some non-mutually-exclusive options for how the §4.5.2 status drive story might turn (approximately) zero-sum:

“Convergent learning” (§4.5.1)—For example, if I have high status, and other people have higher status, and therefore I can’t find mating opportunities, I could notice what’s happening (either implicitly through experience or explicitly through reason), and wind up wanting not just high status, but higher status than other people. I’m sure that kind of thing happens to some extent, although my current guess is that it’s not central.

Envy—I think there’s an innate mechanism in the brain for envy (although I don’t know how it works in detail, see here). I think this mechanism is generic, not specific to status-in-particular. But it would apply to status just like anything else. Thus, if I have positive status (people generally think well of me), but other people have even more positive status, that could leave me feeling miffed, thanks to plain old envy.

A finding-someone-to-blame drive—There seems to be an innate drive that somehow (directly or indirectly) makes people motivated to find someone to blame when things aren’t going well. I don’t know how such a drive works mechanistically in the brain, but if it exists, then one of its consequences would be that there’s a force ensuring that at least some salient people are low-status and reviled at any given time, contrary to the “omni-prestigious society” fantasy story above.

Something else I’m not thinking of.

People seem to be averse to assigning a different valence to Concept X than their friends do. For example, if I think Zoe stinks, then I kinda want other people to think that too; likewise, if I think Marvel superhero movies are better/worse than DC superhero movies, then other things equal, I probably would prefer it if my close friends agree. Is this a separate innate drive? My current guess is no; I think it’s just an indirect partly-learned consequence of the main innate status drive I described above. The story would go like: If my friends dislike Marvel movies, and then my friends find out that I like Marvel movies, then my friends’ brains will now have an association between me and Marvel movies, and per §2.5.1 my friends’ brains will assign a marginally lower valence to me, and I anticipate all this from experience and intuition, and I don’t like it thanks to my innate status drive. Thus, if I like Marvel movies, then I want my friends to like Marvel movies too, and if they don’t, I might lie about it (or change my preferences via strategies parallel to §3.3) to fit in.

In-group versus out-group dynamics could be related to the above bullet point. In particular, perhaps we should operationalize “in-group” as “the people who tend to have similar valence assignments as me, particularly on important and salient things & people”? Again, I’m not sure if that’s fundamental, versus an indirect consequence of something else. But it does seem to be part of the story. In particular, people seem to treat valence assignments as a major type of tribal / alliance signal (cf. applause lights, Simulacra Level 3, etc.)

4.7 My self-esteem (i.e., the valence I assign to “myself”) is not the same as my felt social status. But it is strongly affected by my felt social status

I have a self-concept too, and like all concepts, it has a valence; something like “how good or bad I feel about myself in general right now”. I don’t think this is the same as my felt social status—I think my felt social status comes from the indirect thing I described above, wherein I’m thinking about what other people are thinking about me.

But it is indirectly related to my felt social status. As mentioned above (§4.4), we tend to settle into the same valence assignments as our friends and in-group. For example, if my friends and in-group think that Marvel movies are great, I’m liable to wind up feeling that way too, other things equal. By the exact same mechanism, if my friends and in-group think that I suck as a person, then I’m liable to wind up feeling that way too, other things equal. The previous sentence is equivalent to: “If I feel like I have [high / low] social status, then I am liable to wind up with [positive / negative] self-esteem.”

4.8 Conclusion

I still have some lingering uncertainties, but the basic connection between social status and valence seems really obvious to me in hindsight—almost trivial—and thus I find it weird that I don’t recall ever seeing it in the literature, or really anywhere else. (Old Scott Alexander blog posts are closest.) Has anyone else? I’m very interested to hear your thoughts, ideas, references, counterexamples, and so on in the comments section.

The next post will be the last of the series, discussing how I think valence signals might shed light on certain aspects of mental health and personality.

Thanks to Seth Herd, Aysja Johnson, Justis Mills, Charlie Steiner, Adele Lopez, and Garrett Baker for critical comments on earlier drafts.

- ^

Source: Martha Stout’s book: “After listening for almost twenty-five years to the stories my patients tell me about sociopaths who have invaded and injured their lives, when I am asked, “How can I tell whom not to trust?” the answer I give usually surprises people. The natural expectation is that I will describe some sinister-sounding detail of behavior or snippet of body language or threatening use of language that is the subtle giveaway. …None of those things is reliably present. Rather the best clue is, of all things, the pity play. …Pity from good people is carte blanche… Perhaps the most easily recognized example is the battered wife whose sociopathic husband beats her routinely and then sits at the kitchen table, head in his hands, moaning that he cannot control himself and that he is a poor wretch whom she must find it in her heart to forgive. There are countless other examples, a seemingly endless variety, some even more flagrant than the violent spouse and some almost subliminal.” Also, I’ve known two high-functioning sociopaths in my life (I think), and they were both very big into the “pity play”.

Agreed, and I think the reason is just that the thesis of this post is not correct. I also see several reasons for this other than status competition:

The central mechanism is equally applicable to objects (I predict generic person Y will have positive valence imagining a couch), but the conclusion doesn’t hold, so the mechanism already isn’t pure.

I just played with someone with this avatar:

If this were a real person, I would expect about half of all people to have a positively valenced reaction thinking about her. I don’t think this makes her high status.

Even if we preclude attractive females, I think you could have situations where a person is generically likeable enough that you expect people to have a positive valence reaction thinking about them, without making the person high status (e.g., a humble/helpful/smart student in a class (you could argue there’s too few people for this to apply, but status does exist in that setting)).

You used this example:

But I don’t think it works that way. I think Obama—or in general, powerful people—have high status even among people who dislike them. I guess this is sort of predicted by the model since Republicans might imagine that generic-democrat-Y has high-valenced thoughts about Obama? But then the model also predicts that the low-valenced thoughts of Republicans wrt Obama lower his status among Democrats, which I don’t think is true. So I feel like the model doesn’t output the correct prediction regardless of whether you sample Y over all people or just the ingroup.

(Am I conflating status with dominance? Possibly; I’ve never completely bought into the distinction, though I’m familiar with it. I think that’s only possible with this objection, though.)

Many movie or story characters fit the model criteria, and I don’t think this generally makes them high status. I also don’t think “they’re not real” is a good objection because I don’t think evolution can distinguish real and non-real people. Other mechanisms (e.g., sexual and romantic ones) seem to work on fictional people just fine.

Suppose the laws of a society heavily discriminate against group X but the vast majority of people in the society don’t. Imo this makes people of X low status, which the model doesn’t predict.

Doesn’t feel right under introspection; high status does not feel to me like other-people-will-feel-high-valence-thinking-about-this-person. (I consider myself hyper status sensitive, so this is a pretty strong argument for me.) E.g.:

I don’t think I can. These seem like two distinct things to me. I think I can strongly like someone and still feel like not even I personally attribute them high status. It’s kind of interesting because I’ve tried telling myself this before (“In my book, {person I think deserves tons of recognition for what they’ve done} is high status!”), but it’s not actually true; I don’t think of them as high status even if I would like to.

My guess it that status simply isn’t derivative of valence but just its own thing. You mentioned the connection is obvious to you, but I don’t think I see why.

An idea on 4.6:

I think it can be explained as an incidental side-effect of other stuff that you’ve talked about.

It could be that women’s brains learn that they can channel influence via men interested in them. A stereotype I have heard is that men are interested in women. This leaves the question of how that is genetically wired, maybe via selective attention, but we can maybe take it as an empirical fact. So, if women learn many strategies to harness men’s influence, they will naturally learn that some men have more of it.

I understand your comment as kinda saying “ultimately it is beneficial to women to have relationships with high-status men”.

If so, I think that’s not a satisfactory explanation because:

I think people basically don’t voluntarily choose who they’re sexually attracted to,

Relatedly, I think if Person X expects to benefit (for whatever reason) from feeling sexual attraction towards Person Y, there’s no (within-lifetime) mechanism that translates that fact into an actual feeling of sexual attraction towards Person Y.

Right? Or sorry if I’m missing your point.

sNot quite. But I didn’t think the sexual attraction thing thru either. I think sexual attraction could be two different but correlated things: Seeking out powerful men and sexual feelings toward attractive men. Because power and health correlate and because the halo effect emphasizes this, we may conflate these two.

So I’m saying (medium to low confidence, just-so-story):

A) Women seek out powerful men because of general reward prediction:

Men are paying attention to women (however that happens, but the story is probably alike).

Women learn that their behaviors influence men’s attention and behavior (model prediction).

Women learn that their influence on men is benefiting them (in the sense of grounding out in well-being inputs to the steering system) more if the men are more powerful (reward prediction).

That makes women seek out more powerful men.

B) Independently, women seek out healthy men because of specific sexual attraction:

Men have observable health/fitness/beauty attributes that can be sensed by simple detectors feeding into the steering system (symmetry, depth of voice, some smells).

Women’s steering systems reward some sexual behaviors (“genital friction”).

Women learn to predict reward for such interactions (typically with men).

There must be some randomization for when this mechanism triggers because, as you say, it is quite unpredictable.

But, it is more likely to trigger and get learned to be associated with powerful men because these are sought out more as per A).

Some thought on 4.3

Why would your brain assign positive valence to these thoughts? These thoughts about persons specifically, beyond what it learns of what thinking and speaking and acting related to them entail?

I’m not saying the brain can’t reward such thoughts. It can for sure learn what people are and that people can have an outsized influence on the success of its actions. But I want to drill down on what it would mean if the brain would selectively reward such thoughts. I think there is a risk of self-reinforcing or circularity. Thinking of people is rewarding because thinking of people is warding, so do more of it.

I notice that you do not use the symmetrical expression “respond with negative valence”. Is that because there is no antagonistic “negative valence” neurotransmitter? I know that there are neurotransmitters for stress but it seems that antagonistic learning works differently in the brain than dopamine reward, or?

I feel like you could ask the same question about any valence-of-a-concept (§2.4). Why would your brain assign positive valence to “democracy”, beyond what it learns of what thinking and speaking and acting related to democracy entails? And my answer is: it’s a learned normative heuristic (§2.4.3). By the same token, if, on many occasions, I find myself having a good time in Tom-Hanks-associated movies, impressing my friends with Tom-Hanks-associated witticisms, etc., so my brain winds up with a more general heuristic that I should be motivated by Tom-Hanks-involving things (with the caveats in §2.4.1.1), and then it applies that normative heuristic to novel situations like “other things equal I want to buy a Tom Hanks action figure” or “other things equal, if I learn that Tom Hanks does X, I should update in the direction of X being a good idea”.

There’s an “inference algorithm” (what the brain should do right now) and there’s a “learning algorithm” (how the brain should self-modify so as to be more effective in the future). I’ve been focusing almost exclusively on the inference algorithm in this series. Your comment here is kinda mixing up the inference algorithm and learning algorithm in a weird-to-me way. Like, if my brain right now is assigning positive valence to thoughts-involving-Tom-Hanks, then I will find such thoughts and ideas motivating right now (inference algorithm), but my brain won’t necessarily update those thoughts and ideas to be even more motivating in the future (learning algorithm). That would depend on the error signal going into the learning algorithm, which is a different thing and outside the scope of this series. Does that help?

OK, the more complete version would be

If, when lots of people think of Person X, their brains tend to respond with positive valence, then that fact is related to X having high social status / prestige (as above);

If, when lots of people think of Person X, their brains tend to respond with negative valence, then that fact is related to X having low social status / prestige (as above);

If, when lots of people think of Person X, their brains tend to respond with fear of them (or awe, or something in that vicinity) then that fact is related to X having high dominance.

If, when lots of people think of Person X, their brains tend to respond with lack-of-fear of them (or lack-of-awe, or feeling-of-safety, or feeling-of-the-stakes-being-low, or something in that vicinity) then that fact is related to X having low dominance.

I’m thinking of valence as a signal that can swing both positive and negative, as opposed to a positive-valence signal in the brain and a separate negative-valence signal in the brain. I acknowledge that there are areas in the brain where positive and negative contributions get calculated separately, but I think those pathways mostly get merged back together (positive minus negative) into a final all-things-considered valence signal.

Wait, do you mean this abstractly, or in the sense that there is a signal in the brain (a neurotransmitter etc.) that can be both positive and negative? How would that work biophysically?

A neuron can have a normal baseline of activity, and then be more-active-than-baseline sometimes and less-active-than-baseline other times. Phasic dopamine is the famous example that I especially have in mind here (cf. “dopamine pause” versus “dopamine burst”). I presume there are other examples too, but that’s something of a guess.

Here’s another option: If Signal X inhibits Neuron Group Z, and Signal Y excites Neuron Group Z, then we can abstractly subtract Signal X from Signal Y to get an abstract signal that can swing both positive and negative, and have coherent effects in the brain of either sign, even if there isn’t any one physical signal corresponding to that.

Do I understand correctly that the baseline of tonic dopamine sets the zero point and the bursts or absence of bursts indicate the positive/negative signal around that zero point?

The second option also makes general sense to me. It would more reliably result in absolute reward signals as the zero point is indeed the absence of either signal. I wonder if there are such neuron groups that do have such inhibition properties as you propose.

Yes, that is what I was saying, except “pause” is different from “absence of burst”. E.g.

So 1-8Hz is the baseline / zero point, a “burst” is more activity than baseline, and a “pause” is less activity than baseline.

There’s a beginner-friendly discussion of dopamine neurons in Brian Christian’s Alignment Problem book, if memory serves.

There are inhibitory synapses all over the brain—probably a comparable number to excitatory synapses (I don’t know the exact ratio offhand). Inhibitory synapses often (maybe “usually”) use GABA as the neurotransmitter, while excitatory synapses often use glutamate as the neurotransmitter.

Thanks for the primer.

1-8Hz is quite a range. I guess the base rate is not stable even within an individual. That would imply that the zero point is not actually fix. Given that tge brain can also achieve the effect with inhibitory synapses, I wonder whether there is a reason for this.

I also wonder what would happen if existing neuronal networks were trained with varying zero points. Would that improve learning like dropout is improving generalization?

Great post! I love the whole valence sequence!

I agree with the central thesis 4.2 that social status is defined by Person X’s perception of the positive feelings Person Y has towards Person Z. I also agree with the elaborations in 4.3 and 4.4. I have a tangent question about 4.3 and 4.6 that I comment on separately. But I think your innate status-drive claim of 4.5 doesn’t hold, and the convergent learning (plus other factors) is the more likely explanation. I will reply to your arguments in order and conclude with a specific counterexample and some speculation of my own.

Universality

You can’t have it both ways with the universality. Generality of behavior as proof of genes and variability as proof of genes. First, you say status-drive is universal:

versus saying

If there is inter-person variability, that reduces how universal it is, no? This is more of a nitpick though, because I do not disagree with the examples given.

You also mention other sources for your claim.

how early in life status-seeking starts, how reliable it is

This could also point to status awareness being learned early, which would also explain its universality as we are exposed to social cues very early and existentially depend on the care of other people very early on.

the general inability of people to not care about status

This is evidence, but a weak one because people tend to cling to the status quo, which seems likely explained by a more general mechanism.

Sociopaths

Psychopaths and I also guess sociopaths often have traumatic childhoods, and that indicates a different learning experience and, thus likely other strategies, thus not contradicting the general learning hypothesis. Compare also the 2x2 life strategies suggested in Scott Alexander’s Book Review Evolutionary Psychopathology.

Mechanism

You ask

and you propose

But your hard-wired brain has no way of rewarding this thought specifically! There is no input to the steering system that can distinguish between these thoughts. It can not even distinguish what a person or agent is initially and has to learn that based on cues such as faces and coherent behavior.

And you mention counterexamples yourself I want to flesh out.

Taylor Swift

Explaining this contrast does not require an extra ingredient if you go by learning and predicting outcomes: Your brain will reasonably predict that attention by Taylor Swift might come with a lot of upsides!

High Status

That would be easy to explain as learned behavior—it is just less beneficial to you yourself to be respected if you don’t need the attention—but it would be hard for an adaptation mechanism to lock on.

I want to end with...

A Counter Example

I’m a counterexample. I feel no status-regulating emotions (that I’m aware of). I have often wondered about it. Is it a genetic thing? Is it related to my introversion? One possible explanation I came up with is that I somehow feel high status (without being aware of it). A high-status person doesn’t need to worry about other people’s status and can magnanimously be nice to everyone (and feel even more high-status in response). But that would also be counter to your hypothesis because I required another wheel to explain it.

I asked ChatGPT about it and it suggested that it might be related to my Big 5 type. It speculated that I might be low in neuroticism and high in openness and agreeableness—which I am! It also suggested neurological mechanisms by which status-blindness might be mediated. For example

Individuals high in neuroticism often exhibit a more pronounced response to stress.

Agreableness may be mediated by higher levels of oxytocin and lower cortisol.

I think these point to interesting ways in which genes do influence status regulation.

Sorry if it wasn’t clear. I want to distinguish two things:

Variability across people who grow up in a similar culture and environment — As a rule, I think that kind of thing is often evidence of innate drives rather than convergent learning, because if adopting a certain habit or preference is a robustly good idea, why would only some people do that? (I can think of exceptions; this is just a general rule.)

Variability across cultures — As a rule, I think that kind of thing is usually evidence that innate drives are not directly incentivizing the behavior in question, but rather it’s a learned cultural norm.

I think status drive exists in all cultures, and I also think that within a culture, some people are more intrinsically motivated by status than others. Those both point towards an innate drive, IMO. That’s what I meant, although of course you’re entitled to disagree.

I agree with this restatement. Makes sense. Sorry that I got it wrong.

For any innate drive, there is (and has to be) an innate parameter converting its output into units of valence. And, like any innate parameter, we should expect this parameter to be at least somewhat different in different people (and to be heritable).

Take hunger drive as an example. I think in some people, if the hypothalamus has evidence of slight malnourishment, it translates into strong valence boost for a-plan-to-eat-soon; in other people, the setting of some important parameter is lower, so if the hypothalamus has evidence of substantial malnourishment, it translates into a modest valence boost for a-plan-to-eat-soon. For example, my own children seem to feel almost no desire to eat when they’re hungry; instead they just get progressively more cranky, for quite a while. (I’m sure if they went a whole day without food, they would feel hungry like anyone; also, once they actually start eating, then they “realize” they were hungry.) A more famous example is the well-known differences among dog breeds in food drive. Another example: I think some people just inherently feel pain to be more aversive and distressing than others, in general, holding the physical injury fixed, because of innate “connection strengths” in their brain (or innate sensitivity of the peripheral nerves or whatever). I sometimes get very morally outraged when people misattribute those kinds of innate differences to strength-of-character or whatever.

So by the same token, I think there’s a human-universal calculator in (probably) the hypothalamus that calculates how much evidence of me-having-high-status are evinced by a certain thought, and there’s a conversion factor F such that X units of status-evidence converts to F·X units of valence, and I guess your brain happens to have a low F (so low that the status-calculator has no noticeable downstream effects at all), whereas most other people have somewhat higher F, and some people have much much higher F.

(More realistically, there are probably several innate adjustable parameters that can affect status-drive—not just the one final “conversion factor into units of valence” step, but also stuff upstream of that.)

Fair enough.

Can relate. Same with my kids. Many responses to stimuli seem to be expressed less for my kids and me.

I’d say this points more to a general sensual input weighing though and less to a specific status thing (which would be hard to weight as such abstract things have no absolute grounding).

As mentioned in §4.5.2, I hope to prove you wrong by spelling out a very detailed model of this in the near future. :)

Looking forward to it!