The Story of the Reichstag

When the Red Army was conquering Berlin, capture of Reichstag was seen as an important symbolic act. For Russians, the Reichstag was a symbol of the Nazi Germany. Nazis, however, never used the building, seeing it as a symbol of the despised democracy.

When the building was finally captured Soviet soldiers flew a flag from the roof of the building. The iconic photograph of the moment is not entirely truthful though. Rising smoke in the background has been added a few days later. The editor has also noticed that the soldier securing the soldier who was holding the flag had watches on both wrists. He corrected the error using a needle.

Soviet soldiers, as they were progressing westward through the Eastern Europe, were notorious for looting watches. Some of them were wearing multiple on each wrist.

As the old joke goes: What did marshal Konev say when they were dragging the Prague astronomical clock away? “Часы тяжелые.” (“The times are hard.” or, alternatively, “The clock is heavy.”)

When a footage from Yalta conference was shown in cinemas in Eastern Europe, the sequence where Roosevelt shook Stalin’s hand invariably elicited cries of “Mind your watch!”

To veer off in completely random direction: When George W. Bush visited Albania, the footage of him shaking hands with the crowd shows a watch on his wrist at one moment but no watch few seconds later. Immediately, conspiracy theories sprang up. They were, however, quickly debunked by the White House spokesperson: “The President has not been robbed. He took his watch off.”

Anyway, back to the Reichstag.

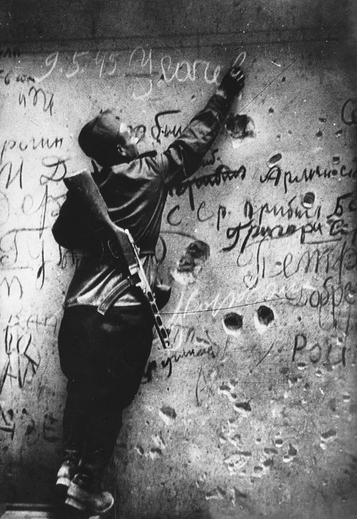

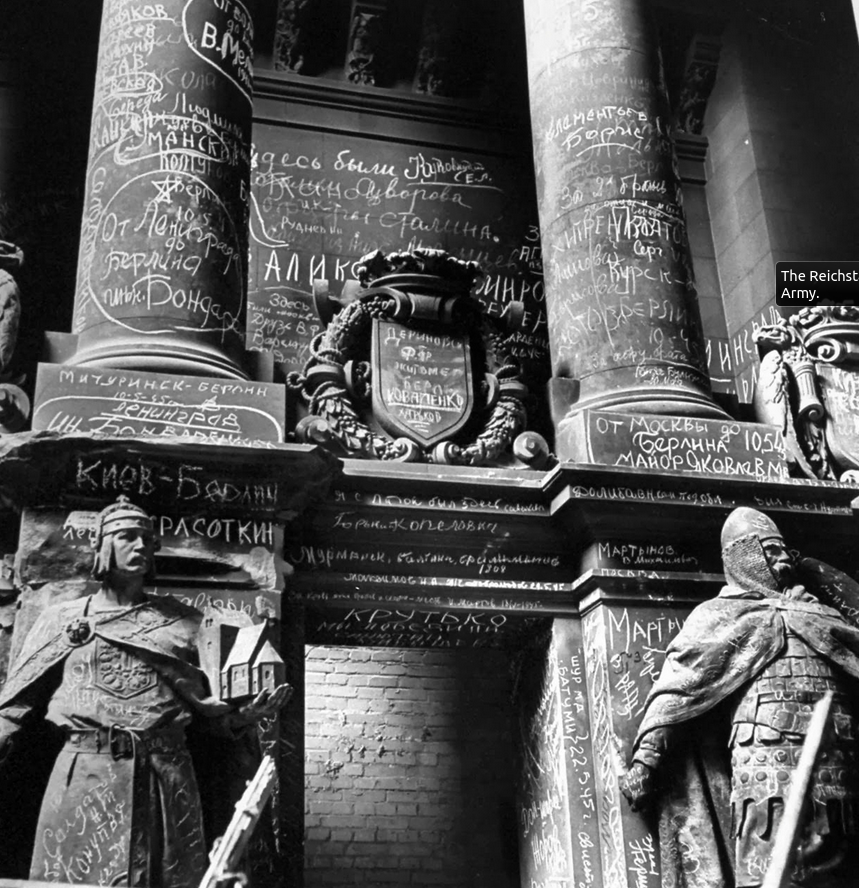

Red Army Soldiers covered the building with graffiti.

These were simple inscriptions saying “Kiew—Berlin. Krasotkin.” “From Moscow to Berlin. Major Yakovlev.” “Sergey was here.” and similar.

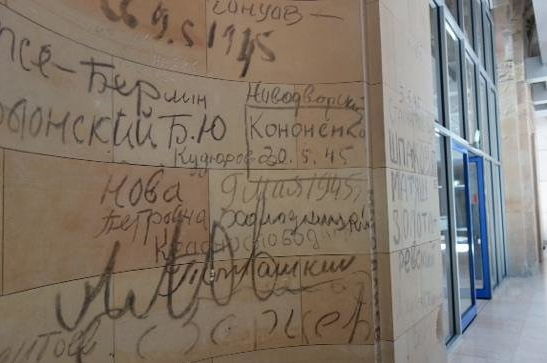

When the building of Reichstag was being repaired after the war it turned out that cleaning the walls would be too expensive. Those were poor times. The builders therefore decided to build clean hallways just by raising a thin smooth walls covering the original walls.

After the unification of Germany, when the Reichstag was being repurposed to become the seat of the parliament once again the builders drilled a hole into the outer wall and discovered that the old Russian inscriptions were still there, untouched.

It was decided to remove the wall and leave the graffiti at different locations in place, on public display.

I think the fact reveals something about the German political culture. I am having a hard time imagining that, say, Americans would keep such a witness of their defeat in the Capitol. That is, if the soldiers from Pearl Harbor were somehow able to get to Washington and leave Japanese inscriptions behind.

What I, personally, like about it is its ambiguity.

The inscriptions can be interpreted in a crude way. As a message to German parlamentarians: Mess it up and you’ll see the Cossacks in the Reichstag again.

But there’s also a much more subtle, even intimate, interpretation. Note how there’s no Stalin’s declaration of victory in the building. But there are graffiti from all those Andreys and Georgiys, common boys dragged out of their villages, sent fighting, killing, being killed, seeing their freinds dying, looting and raping along the way until they arrived in Berlin. Those inscriptions are a reminder that Germany is not an island for herself. That those people, whether she wills or not, are part of her fate as much as they are part of the fate of Russia.

February 5th, 2012

It feels special to be in a place where layers of history just sit there, unerased.

One of our friends back in Moscow was a good tour guide, and I mean good tour guide. A typical yarn from him, just walking along a random street: “That side there used to be a graveyard, as the area was being rebuilt they cut up the headstones and used them for curbs. One time me and a friend flipped one over - ” and he stops and points to a random curbstone with some old, old letters cut into it.

On key insight is that Germany may be the only country in history to have accepted that it was on the wrong side of a war*. This exception explains a lot about the subsequent history of Europe.

As a comparison, official Japanese history has a very ambiguous vision of WW2, and top government officials regularly visit graveyards where war criminal have been buried...

This is something I would like to study one day. There seems to have been a turn in German public attitude at some point. As far as I can say from what I’ve read, it haven’t yet happened in early 50′s. Denazification programme and Nurnberg trials were felt to be a farce a it’s unclear whether they could have contributed to the change. Some public figures (e.g. Adenauer) may have lead by example, but frankly, I don’t know.

If people here, especially Germans, have any insights on the topic, it would be great if they could share.

I haven’t studied this in detail but as a German common knowledge would be that the main change in public attitude came around 1968.

The hippies were influential in challenging the political status quo in many countries and changing the German public attitude towards the Nazis being very bad happened at that time.

There are also lots of different things that happened in the cold war where Germans felt supported by other countries. The military occupation that existed in Germany also allowed the Allies to do various small things to affect German public attitudes.

Nitpick:

Wikipedia mostly agrees with this, except it says the hammer and sickle was original (and shows what it claims to be the undoctored photo). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raising_a_Flag_over_the_Reichstag

The reference comes from Prof. Wolfram Pyta from University of Stuttgart. However, given that Wikipedia disagrees and that the fact doesn’t add any added value to the article anyway, I am removing it.

It’s quite unclear that they are responsible for setting it on fire. It’s basically a conspiracy theory without good evidence and we know from private diaries that top NS personal was surprised that it was set on fire.

Fair enough. I’ve just wrote what I’ve been taught in school. I’ll remove the sentence.

While obviously the Nazi’s did a lot of bad things the winner did write history and that means that conspiracy theory that made the Nazi’s look bad made it into the general curriculum.

Given the state of diplomatic relations between Germany and it’s historical enemies France and Poland, and given the state of diplomatic relations between Japan and it’s neighbours China and Korea, I think the answer is already pretty obvious…

Fascinating anecdote, thanks for sharing!

Why did they fight so hard to defend it then? IIRC the battle for the Reichstag was pretty fierce.

My understanding is that, even if the parliament had no more effective power, it was still used for ceremonial purposes.

The last time it convened was in 1942, when it formally gave to Hitler supreme power.

To be more precise, in a Girardian sense Germany and France where able to reconcile thanks to using the Nazis/Pétain as scapegoats. Hence the factually dubious but politically crucial discourse of both De Gaulle and Adenauer after the war (“Nazis where a minority, Germans where only following out of fear, they didn’t know about the Holocaust” and “from the beginning everybody in France was supporting De Gaulle”). This allowed both countries to cast their culpability away while still accepting that their governments did evil things, and for German to consider the defeat as a liberation. In Japan, the only condition of the capitulation was that the Emperor would stay on the throne. This made it impossible to operate the same scapegoating and this is why Japan has such an ambiguous attitude toward the war (plus the atomic bombs gave them a very good reason to present themselves as victims, even if the destructions at Hiroshima and Nagasaki where not really different from classical bombings such as Tokyo or Dresden).

Point taken.

Still, it feels a bit different. The 9/11 memorial is honoring the good Americans killed by the bad terrorists. But the inscriptions in the Reichstag are definitely not honoring the good Germans killed by bad Soviets. They were, after all, whether willingly or not, fighting for the Nazis. But neither are they honoring the Soviets. They were fighting for Stalin, for the Stasi, for Berlin families being separated by the Wall. It’s hardly a memorial at all. If there’s any moral to be taken, then it is that history is, in the end, not about the good and the bad, but about Alexey from Pskov and Hans from Göttingen, maybe neither of them a particularly good person, but both of them being swept alike by the uncaring forces of history.

-

That doesn’t seem in the same ballpark to me.

-

Nagasaki and Hiroshima and the Rape of Nanking are generally considered atrocities rather than military victories. They aren’t shameful or embarrasing to remember (for the victims.) Pearl Harbor was an early defeat in a war the US eventually won handily.

A better comparison would be if the US had a memorial to the time the British burned the White House during the war of 1812. Maybe they do, but if so I haven’t heard of it. I guess this is a test we could do!

That somehow doesn’t feel quite right—something of a different class of things, unless you’re saying that the general American perception now is we deserved the attack.

I would think perhaps the Vietnam War memorial might be a better case—still not quite the same (I might even go as far as to say something of a mirror image).

-