We know that Molochian situations are everywhere, from the baggage claim to the economy. It’s a metaphor that helps us understand the pernicious nature of negative-sum games—when our rational short-term individual decisions create a system that is detrimental to all, making us complicit in our own subjugation.

But what about the foundational story? What should the original victims of Moloch do?

I mentioned in Who is Moloch? that the Canaanites were acting rationally by offering the occasional child for sacrifice, but that’s not entirely true. We can actually find an optimal strategy through using some Game Theory!

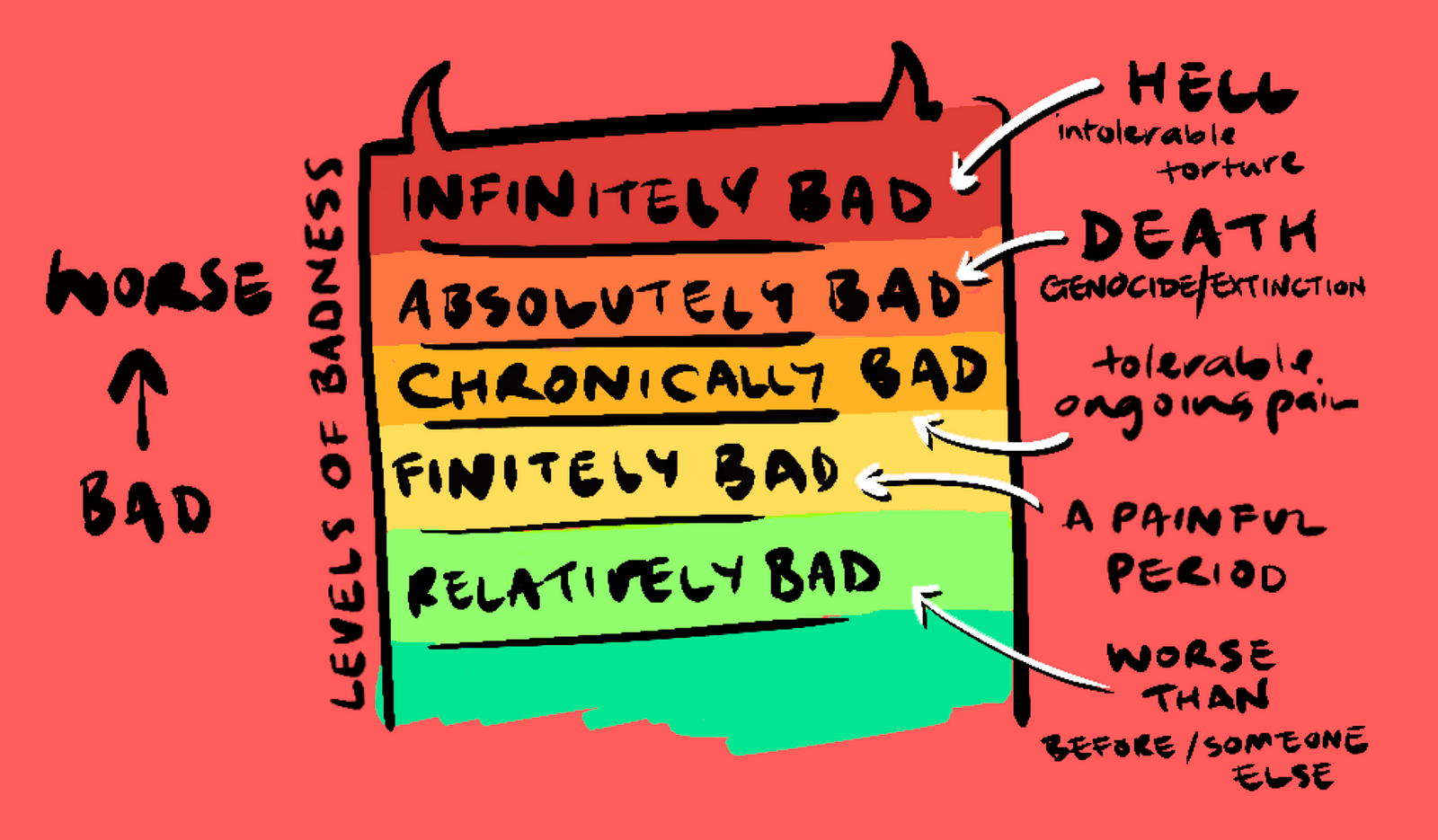

Right now we have a chronically bad situation. So, if on one hand, the tyrant can and will destroy literally everything, this is an absolutely bad outcome, a game-over scenario, this is indeed worse than a chronically bad situation. But if there is a chance that some of the population can survive the consequences of refusing to submit, leading to the starvation of Moloch, then you are measuring a chronically bad situation with a finitely bad situation. And a situation that is finitely bad, as long as it is not absolutely bad (game over) is better than a chronically bad situation.

So. the optimal solution is to rebel and starve the tyrant.

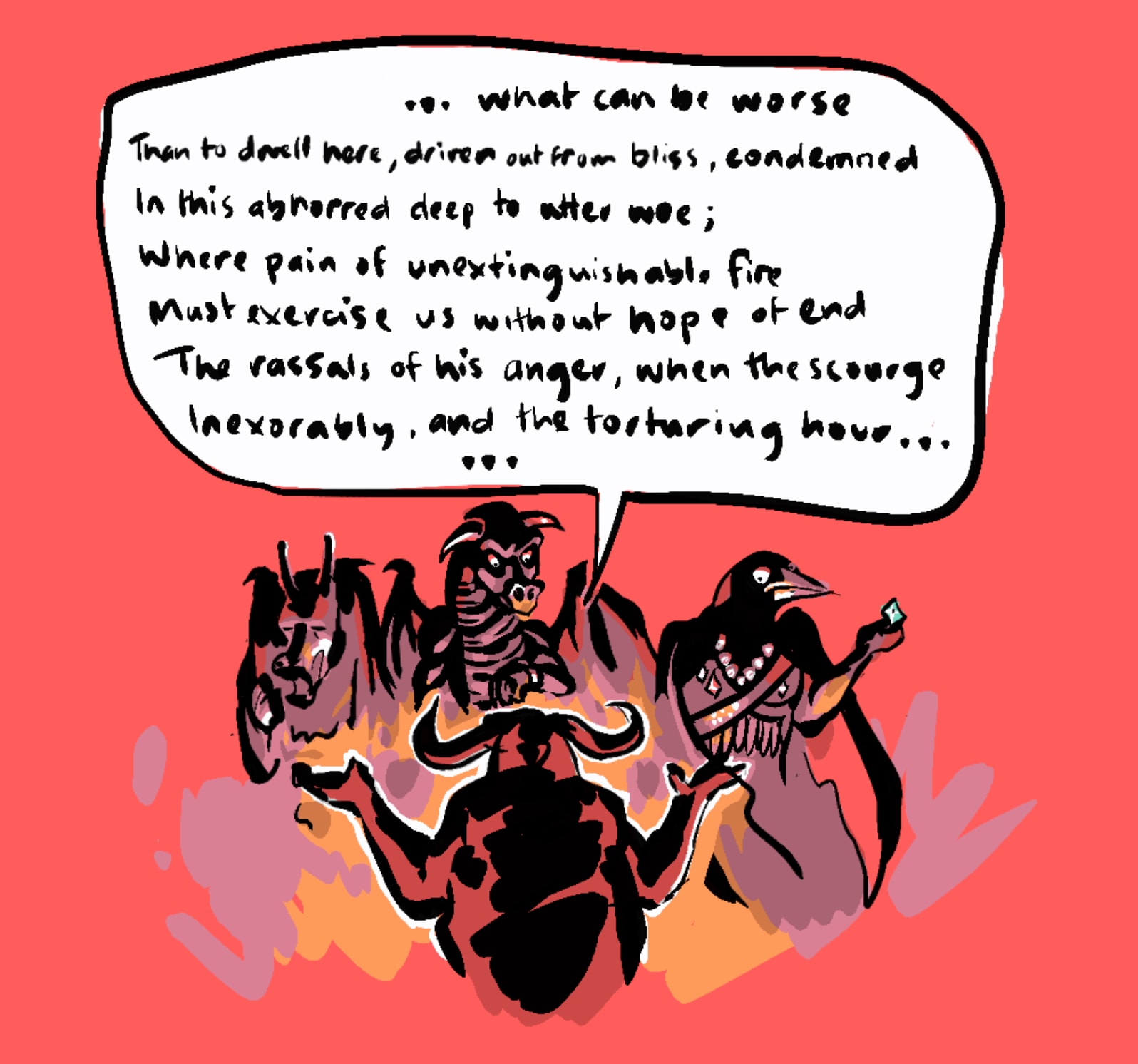

Ironically, in John Milton’s Paradise Lost, this is the path for which Moloch advocates when addressing his wretched compatriots; open war against God. Now, Satan famously stated…

“Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heav’n” — Satan

Moloch goes one further, to propose (and I’m paraphrasing) that it’s even better to risk death attempting to conquer Heaven, than to rule in Hell.

But this is not the only answer. When we look closer, a better solution becomes evident. The Bible portrays the Canaanites (Moloch’s victims in this case) as a war-like, expansionist culture—an account we should approach with some skepticism, given that it also endorses genocide against the Canaanites. Nevertheless, for the sake of argument, let’s accept their allegiance with Moloch is precisely to gain his support for their perpetual conquests (which is right up the belligerent Moloch’s alley). So, it is actually the desire for conflict and expansion that is driving this unhappy arrangement. Let go of that mandate, and they no longer need Moloch—problem solved.

So…

In Game Theory we are often given an alternative with regards to solutions. This solution however, serves as a reminder that beyond theory, in the messy throes of real-life dilemmas, it’s often crucial to seek out a third option, one that’s beyond the established parameters.

It only works so long as the Cannanites can be assured that they can get the resources that they need to support their growing population without inevitably coming into conflict with the neighboring Israelites. For the vast majority of human history, this has not been the case, as the only resource that really mattered was (agricultural) land. An empire that wishes to support more people requires more land, and if the neighboring lands are already claimed, they must be taken, by force.

The choice isn’t between fighting a war and doing nothing, the choice is between fighting a war and slow starvation.

True, though there are many examples of conquerors who expanded for the sake of an expansionist philosophy or glory: Alexander the Great, The Mongols, The Assyrians, The Crusades… off the top of my head. The Germans in WWII definitely justified expansion for the sake of living space (Lebensraum), so there are examples of expansion at least being justified in the way you mention. And of course colonialism is justified in the same way.

I think what you’re saying is logical, but the example, being metaphorical, is more to illustrate that we should question critically what it is we actually want before conceding a price to pay for it. As you say, it might be necessary, but it also might not.

The corollary to my point is that it does no good for the Cannanites to abandon their expansionist ideology unless they can ensure that the Israelites, Philistines, Egyptians, Assyrians, and everyone else also commits to peace as well. In the absence of a general forswearing of expansionist ideologies, one faction committing to abandoning expansionism is unilateral disarmament.

We actually have an example of this: Japan. From 1633 to 1639 the Tokugawa Shogunate imposed a set of policies that banned expansionism, foreign trade, and expelled representatives from European countries. In the process, Japan gave its up its firearms and reverted to the sword. Because Japan was an island nation, without any major known natural resources, far from the then-existing trade routes, they were able to get away with this policy for quite a long time. But quite a long time isn’t forever, and in 1854, the outside world came knocking.

I take your point, it requires everyone to behave themselves (I’m actually familiar with this history, I went down a Japanese history rabbit hole about this time last year, fascinating), but if we continue with Japan we find that due to a third option of trading-with-other-nations (beginning with the Meiji restoration I think...) Japan continues to operate as a sovereign nation without the need to expand (with the exception of its ill-fated and frankly bonkers attempt to expand in WWII...).

So, again it’s good to look for answers outside the paradigm of expand or die. Cooperation and trade are non-zero-sum options that are available in the messy and therefore less theoretically-bound real world, as opposed to a formal game theory scenario.

But I think the expansionist trap you describe is a real thing and an important cautionary tale, which could perhaps be applied to our modern perpetual growth model of economics and its attendant consumerism (here I am sounding like a first year sociology major).

Japan switched hard from isolationism to expansionism almost immediately after the Meiji restoration. This started with the first Sino-Japanese war, in 1894, during which Japan invaded and annexed Korea. This continued with the Russo-Japanese War of 1905, where the Japanese defeated the Russians and took control of Port Arthur and the Sakhalin Islands. This continued with the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931, which eventually bled into World War 2 after the Japanese preemptively attacked the US in order to enable their expansion into Southeast Asia.

During this time, the Japanese self-consciously adopted the ideological, governance and military structures of expansionist European nations in order to avoid being left behind and dominated. That’s why the Japanese parliament is called the Diet, a German word. The Japanese Navy was explicitly modeled after the British Navy.

It was only after the Japanese were thoroughly defeated by the United States and Soviet Union that they transitioned to their current model of focusing on commercial success over military expansion. They were able to do that because, in the wake of World War 2, they were given explicit security guarantees by one of the two major global hegemons at the time.

Ah, yes now you’ve jogged my memory about all the attempted expansionism in between. You make a solid case that they didn’t step outside of the expand-or-die dichotomy willingly.

The point I’m trying to make is that the third option was there (perhaps it wasn’t feasible before WWII, I’m not sure), but the third option (mutually beneficial trade and cooperation) ended up sustaining Japan from WWII to the present without the need for expansion.

The point of the post is that often there is often a third option outside of expand-or-die, and it’s worth questioning what that could be in any given problem. But thanks for all the very good points—I absolutely agree with you that there have been civilisations that have had to, or have seemed to have to, expand in order to survive. Thanks for your well-considered points, and the spot-on history (apologies for the patchiness of mine).

First, I agree with the ultimate point that looking for creative solutions is the right approach to many real-world problems. Harsh tradeoffs are real sometimes, but you should really make sure you’re exhuasting your options before accepting them. And don’t trust leaders who assure you “we’ve got to sacrifice to Moloch,oh and that also means I get to stay in charge”.

A nitpick: starving Moloch is only a better solution if you care about everyone and not just yourself. Humans profess to care about everyone a lot more than they really do, becuase doing that (and even thinking that) is strategically useful.

But when it’s time to make decisions like “should we refuse to sacrifice even though half of us will be killed”, people make much more selfish decisions. A 100% chance of living under Moloch usuallly sounds better than freeing your descendents from Moloch but accdepting a 50% chance of dying.

That’s why Moloch is a problem, so solutions need to address the individual perspective.

A bit bleak… but yes, your logic checks out, and hence why coordination problems are so sticky (I did sort of claim to solve the problem didn’t I? Oops, back to the drawing board).