Extreme outcomes drive tax revenue

Power Laws

Let’s do a thought experiment.

The year is 1800. You’re a loan officer at a bank. Farmers come to you asking for a loan—maybe to purchase new equipment, buy more land, or make investments to improve their farm’s productivity. What are your criteria for granting a loan?

You’ll primarily want to do 2 things: avoid the losers, and reduce risk. To avoid the losers, you’ll want to learn about a farmer’s reputation and character. Are they honest and hard working? Do they have any major vices that might undermine their productivity? To reduce risk, you’ll assess the value of their collateral. How valuable is the land the bank would repossess in the case of a default?

In short, you’re much more interested in minimizing downside than you are in maximizing upside. Why? Well, giving a loan to an excellent farmer probably isn’t going to make you much more money than giving a loan to a median farmer. If a farmer has an incredible yield and produces 3x more than expected—which is very unlikely—you don’t get paid 3x the interest. Your goal is to maximize the number of loans in your portfolio that don’t default. Most of your loans are given to farmers with fairly consistent profiles—similar plans, business models, skill sets, and characteristics. You’re hoping for a consistent batting average, and you aren’t counting home runs.

Now, let’s jump to the present. Instead of a loan officer, you’re a venture capitalist, investing in early stage startups, hoping to maximize the value of your fund. How does this change your criteria?

As a VC, extreme outcomes drive the return on your fund. Accordingly, you care more about unique advantages and differentiators that give a startup a chance at becoming the winner in its category. Most investments will lose money, and many will go to zero, so the structure of financing needs allows for uncapped success when you pick a winner. You want to bet on startups that, if massively successful, could return the value of your entire fund or more.

The difference is that venture capital is ruled by power laws. Unlike a normal distribution, power laws mean that extreme outcomes drive the average, making the average very different from the median or most common outcome. This is how a VC can make money even though most investments fail—the average is pulled up by outliers.

In a power law world, landing big wins is more important than reducing downside in the median scenario.

Income tax returns follow power laws

The vast majority of the US Government’s revenue are taxes on the earnings of citizens. Human capital is the primary asset of the US Government. And those tax returns follow power laws.

According to the Tax Foundation, the median taxpayer earns about $47,000, and likely pays around $3,300 in federal taxes. The average federal tax paid is $14,279 - over 4x higher than the median. Extreme values at the top pull up the average.

Despite frequent proclamations to the contrary, high earners pay a disproportionately large share of federal income taxes. The top 1% pay close to half of all federal income taxes. The top 10% pay over 75% of all federal income taxes.

Source: Tax Foundation

This does not mean we need to lower taxes on the wealthy. It suggests that any increased yield from minor improvements at the top are likely to dwarf the potential savings in the bottom or middle. Resources might be better spent helping more Americans become high earners without too much concern for breaking even on the median citizen. Like a VC, we could focus more on increasing the number of home runs and less on a consistent batting average.

Despite this, attitudes across the political spectrum tend to focus more on minimizing downside risks—like the loan officer—rather than optimizing upside potential. On the right, the priority is often to limit spending on social services and encourage self-reliance with minimal government support, essentially cost cutting at the bottom. On the left, public spending aims to “level the playing field” rather than empowering high-potential individuals to maximize their productivity and raise the standard of living for everyone, overlooking the disproportionate gains to be had at the top.

In an agrarian society of the past, the “loss minimization” perspective probably made sense. For instance, would extensive formal education result in 10x returns from a society of pre-industrial farmers? That seems unlikely. It was more practical to focus on helping the median citizen become moderately productive, and prevent too many individuals from becoming burdens to society.

In today’s power law society, it’s more productive to focus on hitting home runs.

Outsized Returns

Another way of thinking about this is to put yourself in the government’s shoes.

Let’s say I make you a deal: I’m going to pick a random high school graduate and give you their share of tax revenue, forever.

What would you do to maximize the value of this investment? Would you encourage taking the first minimum wage job available, or spending time learning and exploring to find a career in which they could thrive?

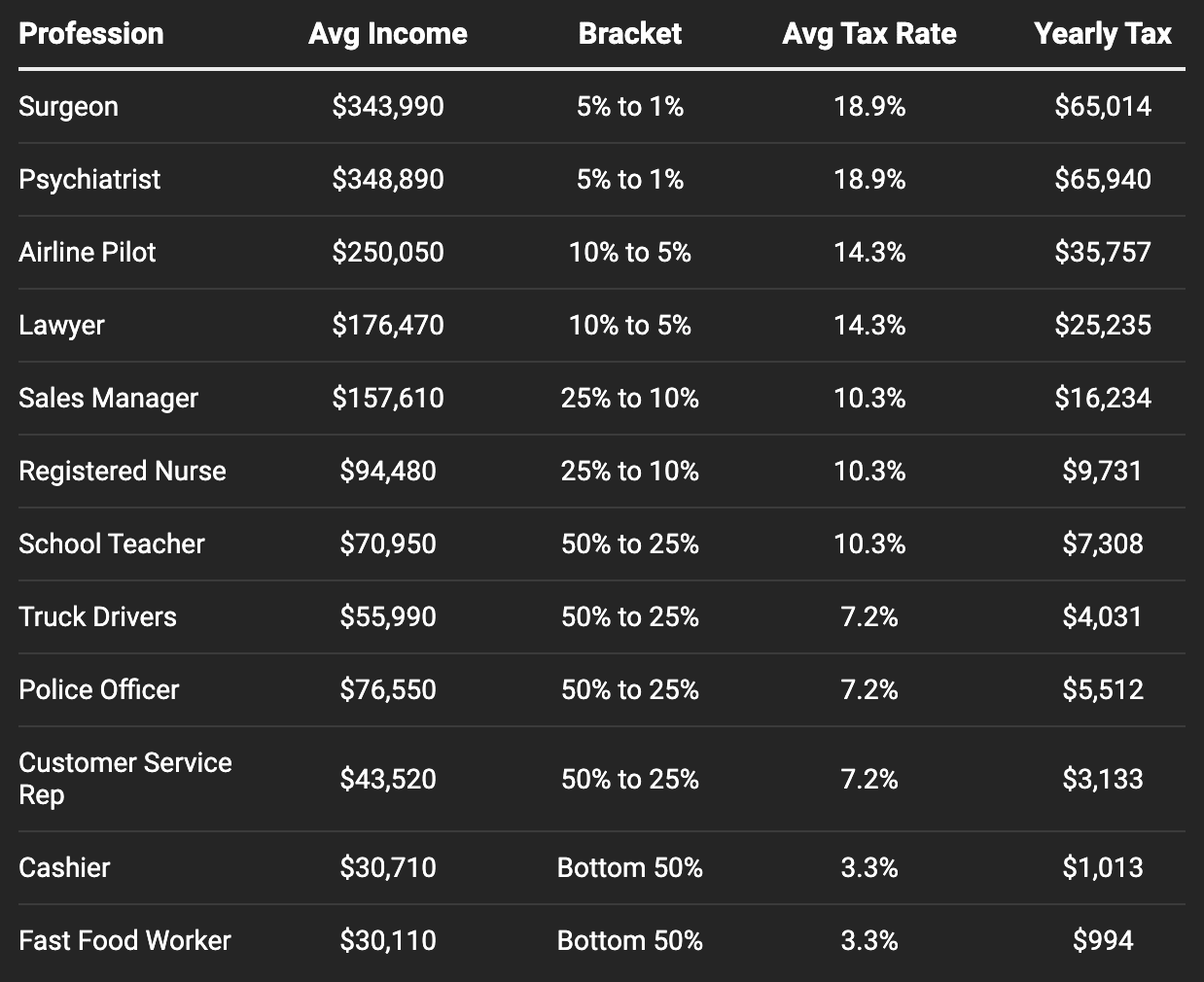

Looking only at federal income taxes, this is how much your investment might return every year depending on which income bucket they fall into.

If you’re unlucky, and you decide not to invest in your graduate, the student might fall into the bottom 50% of earners. Your graduate might make $30,000 a year as a cashier, and you might make $700 a year. If you get this for 40 years, you’ll have collected $28,000 over your graduate career.

If your graduate manages to make it into just above the top 50% - perhaps as a truck driver making $56,000 a year, or a police officer making $76,000 a year—you might make $5000 a year, or $200,000 over 40 years. This is already 7x higher, and neither of these careers requires a college education.

A graduate who makes it into the top 5% might be sending you $65,000 a year.

Here’s a sampling of options, along with what your yearly federal tax return could look like over the course of their career.

Incomes from Bureau of Labor Statistics; Tax brackets from Tax Foundation

But of course, average stats for various careers don’t do justice to the power laws at play, because they don’t capture the chance of your graduate becoming a massive success. If your graduate makes it into the top 1%, on average, they’ll be sending you close to $700,000 dollars every year.

Even distribution within the top 1% is also dominated by power laws—so this average is likely much higher than the median return within the 1% - again suggesting a focus on big wins.

What would a private equity firm do, presented with the same deal, for an entire underperforming school district? Would they optimize for short term self-sufficiency, or invest heavily to produce as many high earners as possible? It’s hard to know exactly how, but I suspect they’d find a way to turn at least some of those kids into home runs.

Focus on Home Runs

What would this look like? Similar to a VC, it could mean focusing more on unique differentiators and prioritizing big wins over median losses.

This might manifest in many different ways across public services.

In public education, we might focus less on proficiency across a standard set of skills and instead cultivate individual superpowers to give students a chance at becoming top performers in specific categories. We might double down on gifted or high-performing students, fully recognizing the benefit they bring to society by realizing their potential.

While there are a wide variety of programs to support the jobless, including limited reskilling and retraining, many of these programs focus on immediate needs and self-sufficiency, and less on helping individuals become positive-ROI in the long term. Instead of encouraging the jobless to accept the first minimum-wage job available, we might enable taking time to learn high-value skills, or starting a business. If even a small percentage of participants become high earners as a result, it could quickly recoup the overall costs of such a program.

Similarly, public discussion about immigration often focuses on perceived costs rather than the potential for tax revenue. High-skilled immigrants, especially those on H1B visas in sectors like tech and healthcare, often earn salaries well over $160,000. Unfortunately, the demand for H-1B visas far exceeds supply, even though each additional immigrant in this category generates substantial positive tax revenue from the outset—enough to offset public spending for multiple individuals in the bottom tax brackets.

We might actively seek out and invest in underutilized talent or underemployed high-potential individuals. We might even allow anyone to apply for an open-ended grant to dramatically increase their own earnings potential, contingent on presenting a feasible plan to do so. Today’s internet makes it possible for anyone with the time and will to learn almost anything at a low cost. A relatively small grant might give someone on minimum wage—making $15,000/year—the free time they need to learn a new skill over six months that could quickly 10x their earning potential. If just a small percentage of recipients make it into high-paying careers, the initial investment would be recouped many times over.

These are just hypothetical examples that may or may not work in practice, but they serve to highlight the lack of policies focused on unlocking major potential gains at the top. While the best interventions might not be immediately obvious, any properly incentivized party would aggressively invest in finding out which ones work, because of the massive upside of any success.

In our power law world, helping a small proportion of the population achieve high-earning potential generates returns that can cover generous benefits for everyone else. Home runs pay for a lot of strikeouts.

Human capital is the US Government’s primary asset, and in today’s day and age, those returns follow power laws. We should start acting like it.

It would be cool if we could get more than 1% of the working population into the top 1% of earners, for sure. But, we cannot. The question then becomes, how much of what a top 1% earner earns is because they are productive in an absolute sense (they generate $x in revenue for their employer/business), vs. being paid to them because they are the (relative) best at what they do, and so they have more bargaining power?

Increasing people’s productivity will likely raise earnings. Helping people get into the top 1% relative to others, just means someone else is not in the top 1%, who counterfactually would have been. Your post conflates the two a bit, and doesn’t make the distinction between returns to relative position vs. returns to absolute productivity, measuring a “home run” as getting into the top x%, rather than achieving a specified earnings level.

If I look past that, I agree with the ideas you present for increasing productivity and focusing on making sure high-potential individuals achieve more of their potential. But… I am somewhat leery of having a government bureaucracy decide who is high potential and only invest in them. It might make more sense, given the returns on each high potential individual and the relatively small costs to making sure everyone has access to the things they would need to realize their potential, to just invest in everyone, as a strategy aimed at not missing any home runs.

Hey @Myron Hedderson, thanks for reading and for the thoughtful comment!

The 1% in this article is just a proxy for that level of success—we claim is that we can grow the number of people who achieve the level of success typically seen in the top 1%, not that we can literally grow the 1%. Productivity and the economy isn’t zero sum, so elevating some doesn’t mean bumping others down (although I acknowledge that there are some fields where relative success is a driver of earnings).

I agree I could have been more clear about this a little bit, and I considered it—I just thought it was a bit of a distraction from the core point. Maybe I was wrong :) I appreciate the feedback.

“I am somewhat leery of having a government bureaucracy decide who is high potential and only invest in them.” − 100% agree with this point. I see this mostly as pushing for a better way of allocating efforts and budgets that are already being spent, but I like your framing around marking sure “everyone has access” instead of picking winners.

Your black table of income levels and taxes paid has something wrong with it. I looked at the Tax Foundation link you provide, and it says something rather different from what you report.

Here is how I read their numbers compared to yours

Top 5%: 23.3% rate vs. your 18.9%

Top 10%: 21.5% rate vs. your 14.3%

Top 25%: 18.4% rate vs. your 10.3%

Top 50%: 16.2% rate vs. your 7.2%

I also note that your row for School Teachers has the same bracket as truck drivers and police officers, but the rate for teachers is from the next bracket up.

Hey @NeroWolfe.

I think you’re looking at the wrong numbers. For example, their 23.3% for the top 5% INCLUDES the top 1%, which skews the averages precisely because of the power laws at play.

The have another table further down where they break this out:

In many ways, that’s an odd framing of the question(s) at hand: governments don’t just blindly try to maximise their tax revenue/the state’s productive capacity (although maybe they should do more of that?), and to some extent there are good reasons why they don’t (the very many citizens who are never going to make it into the top 1% — because that’s what one percent means — certainly prefer it if the tradeoff is a little more in their favour, and for mostly good reasons), etc.

Yours is a political opinion I agree with — it means that governments should help people I like, and fund stuff I find cool and important to have! — but if someone comes up and say to you that they care much more about other things than being maximally productive as a country, I don’t see arguments to reply to that in your post.

In that respect, the way you framed that as “productive people give the government more revenue” rather than something like “productive people build cool stuff everyone gets to enjoy” is interesting, but also makes it easier for someone to say that they just care about other things. All that means that, to me, this post sounds a lot more like a political opinion than the average LW post.

I wholeheartedly agree with the general idea, though: especially in my corner of Europe, people don’t seem to be very encouraged to try things and maximise the amount of interesting/important things they do, at least not as much as in the Bay Area, and I’d love to live in a world where people improve themselves more and do cool stuff more.

Hey @TeaTieAndHat, thank you for the comment!

I think the core idea I’m trying to get across—and the reason I hoped this was a good fit for LW—is not about how govs can maximize revenue for its own sake, but that as a society we could do a much better job caring for the 99% by acknowledging the power laws behind wealth creation and focusing more on increasing our yield at the top.

This is true even if your goal as a government is NOT to maximize productive capacity, because cost / revenue is the bottleneck preventing you from funding everything else. Shifting policy to take advantage of this could let us better support all the “non-productive” things we care about: higher safety nets, public arts, etc.

So for example—if your goal as a country is to raise the standard of living via benefits to the bottom 50% of earners, unintuitively, the best to fund this is to help more high-potential folks become high-earners. Moving a single person from the 5% to the 1% generates enough revenue to pay for many dozens of basic incomes in the bottom quartile.

Thanks again for the thoughtful read and the feedback!

Yeah, I know that, that it’s just that you decided to approach the problem from that angle. And, on the one hand, it was more interesting that way, but on the other hand I was a bit surprised, basically, by what that framing ended up bringing forward vs leaving in the background — re-reading my comment, I still agree with the facts of what I said, but my tone was a bit harsher than I’d wanted.

In fact it’s very interesting: I’m still not surprised that governments don’t do it the way you suggest they should, because people in the bottom 99% want to be treated as well as people in the 1%, or because they prefer to be helped rather than left behind and then given money, etc., but I agree that it would in principle work better the way you describe, and that we often neglect that!