Summary of John Halstead’s Book-Length Report on Existential Risks From Climate Change

1 Introduction

(Crossposted from my blog—formatting is better there).

Very large numbers of people seem to think that climate change is likely to end the world. Biden and Harris both called it an existential threat. AOC warned a few years ago that “the world is going to end in 12 years if we don’t address climate change.” Thunberg once approvingly cited a supposed “top climate scientist” making the claim that “climate change will wipe out humanity unless we stop using fossil fuels over the next five years.” Around half of Americans think that climate change will destroy the planet (though despite this, most don’t consider it a top political issue, which means that a sizeable portion of the population thinks climate change will destroy the planet, but doesn’t think that means we should prioritize it over taxes and healthcare).

I was taught by my science teacher in ninth grade that climate change was an existential threat—and for a while, I believed him. But for the last few years, I’ve thought that this was seriously overhyped. While climate scientists sometimes make hyperbolic statements about climate change ending the world in their role as activists, this is not the consensus view and it’s not the view that all but a small number of climate scientists seriously endorse.

To get to the bottom of this dispute, I decided to read John Halstead’s report on existential risks from climate change.

Halstead’s report is the most detailed report on existential risks from climate change to date. It tries to comprehensively lay out all the ways that climate change might cause extinction and spans hundreds of pages. It was also thoroughly vetted by 19 experts.1 Its conclusion: climate change is not an existential risk of more than negligible likelihood. The odds that climate change kills everyone are very near zero. Halstead summarizes “my best guess estimate is that the indirect risk of existential catastrophe due to climate change is on the order of 1 in 100,000, and I struggle to get the risk above 1 in 1,000.”

If this is correct, and indeed I think it is, then a major portion of the Democratic party has been engaged in outrageous hyperbole. They are claiming a high likelihood of existential catastrophe from something with odds of existential catastrophe well below one in a thousand. This would be a bit like someone claiming that we’ll all die unless we eradicate malaria in the next decade. While it has become fashionable to call out climate denialism on the right—as, indeed, it should be—we should not neglect the perhaps even more common form of climate denialism on the left.

Falsely telling people that we’ll all die soon unless we torpedo the global economy is quite a pernicious form of misinformation, leading to both mass terror and support for dangerous policies. We should be worried about climate misinformation on the left for the same reason we should be worried about it on the right. When people have a wildly distorted picture of the scale of some problem—whether they downplay it or overestimate its severity—this is incredibly dangerous. Falsely believing that something will kill everyone on the planet is not a minor error.

Yet errors from those on the right are also serious. Climate change is likely to increase wild animal suffering2 by staggeringly large amounts. As we’ll see, climate change is likely in the long run to lead to vastly more organisms suffering and dying painfully. It will also probably kill many millions of people. So while it probably won’t doom the world, it’s quite a bad thing, and I’d generally be supportive of taking more actions to address climate change.

Here’s the plan for this essay. Each section will be about something bearing significantly on the climate change debate. Specifically, what the sections will be about is:

How much warming there will be.

How past warming periods have gone.

How warming will likely affect agriculture.

Whether warming will trigger ecosystem collapse that will annihilate global agriculture.

How warming will affect heat stress and sea level rise.

Whether warming will trigger tipping points.

Economic costs.

Impacts on migration.

Impacts on global wars.

Section 11 will conclude and draw various takeaways from the previous discussion.

2 How much warming will there be?

You rarely hear about the amount of progress we’ve made on climate change. For a while, various models predicted much faster growth in CO2 emissions than we in fact observed. More recent models have been more optimistic about how much warming we’ll observe. There are a few reasons for this.

First, the cost of renewable energy has gone down drastically. This has been dramatically underestimated. Halstead writes:

Historically, models have been too pessimistic on cost declines for solar, wind and batteries: out of nearly 3,000 Integrated Assessment Models, none projected that solar investment costs would decline by more than 6% per year between 2010 and 2020. In fact, they declined by 15% per year

This chart from Our World In Data shows just how rapidly solar costs have declined:

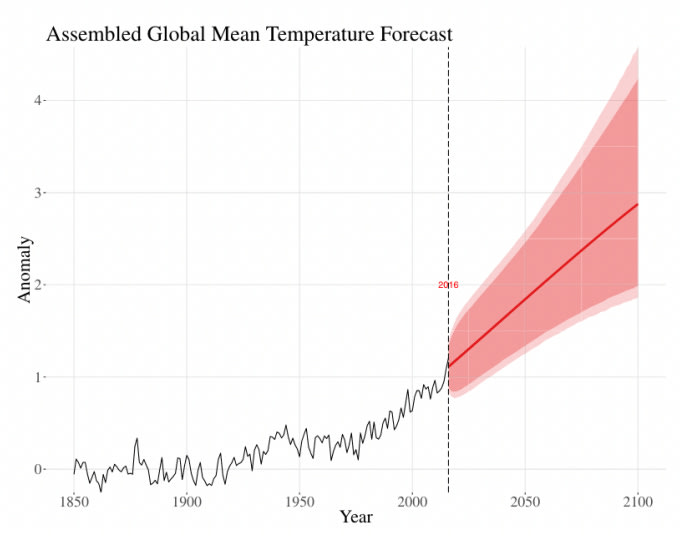

Second, countries have taken more dramatic climate action than was anticipated. Countries representing 2⁄3 of global emissions have committed to net-zero by 2050. China committed to net zero by 2060. In many cases, countries’ GDP has risen while their emissions have fallen. For these reasons and others, those predicting future emissions have generally grown more optimistic over time. One representative temperature forecast comes from from Liu et al:

After reviewing a great battery of studies from Liu et al, Meinshausen et al, Climate Action Tracker, and more, Halstead concludes “On current policy (i.e. RCP4.5), by 2100 we are most likely to end up with around 2.7°C of warming and there is a 1 in 20 chance of more than 3.5°C… “the chance of more than 6°C of warming is on RCP4.5, …seems likely well below 1%, given that the upper 95th percentile is 3.5°C.” Scenarios with very rapid warming of 8 degrees, for instance, are vanishingly unlikely.

(Though see here for a different perspective with significantly higher credence in extreme warming scenarios. What that post argues is that we shouldn’t have as much credence in mainstream climate models, so very high warming scenarios aren’t as unlikely as Halstead claims. The author is someone I know, and he’s extremely smart and studied Earth science, though overall, I lack the expertise to evaluate who is right. In either case, risks are fairly low.)

3 How past warming periods have gone

There have been some periods in the past during which high releases of CO2 correlated with mass extinctions. During the end Permian disaster, volcanic activity released huge amounts of CO2 and other gasses—with devastating effect. About 90% of marine species died off, and species on land fared little better. Yet this was unlikely to be mostly caused by CO2, as historically species have been relatively proficient at surviving higher CO2 concentrations.

Surprisingly, in the geological record, high CO2 concentrations are usually correlated with flourishing and abundance, not mass die-offs.

During the Mid-Cretaceous period, for instance, “temperatures were around 20ºC warmer than pre-industrial levels, while CO2 levels were between 500ppm and 1,000ppm.” Despite this, the rate of species extinction did not increase. During the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, temperatures went up 5°C over just 3,000 to 20,000 years. It was much hotter than it is today. The same was true during the Eocene. Despite this, rather than having species extinction, there was a period of rapid growth in organism number and biodiversity. And the same was true of the warming periods during the Miocene, Mid-Pliocene, the last interglacial, and the transition into the Holocene from the last glacial.

However, these were in the distant past and warming is likely to be much less rapid during them than during the present day. Thus, they’re not entirely representative but they still tell us something. The transition into the Holocene was most recent and had most rapid warming, so the fact that there was mostly just shifts in the distribution of species without much extinction gives some reason for optimism.

While some claim that climate change was responsible for the recent mass extinction of megafauna—of the wooly mammoth, giant ground sloth, etc—this isn’t the most likely scenario. Probably it was caused by humans overhunting these creatures. This is because:

Most of the mass extinctions followed shortly after humans first entered a continent.

Only big animals went extinct, which makes sense if we were hunting them but is otherwise unprecedented in Earth’s history.

Most of these animals evolved more than a million years ago and survived many warm periods. It would be unlikely that they’d all suddenly get wiped out by a warm period right before our existence.

In fact, during the warm period from the Pleistocene into the Holocene, humans survived and flourished. Humans at the time mostly lived in Africa. Survival was much more precarious than it is today, given the existence of modern technology. Thus, if we survived before, that’s at least some weak reason for optimism.

Now, it’s true that before the breakup of Pangea, warming periods generally led to mass extinctions. But this hasn’t been true for hundreds of millions of years—since the breakup of Pangea. Why is this? One answer is that the ecology of Pangea made it bad at removing CO2 from the atmosphere. Another is that these extinctions were often combined with large amounts of volcanic activity. Pangea’s geography made it very vulnerable to the gasses released from rampant volcanism.

The overall takeaway from this section is that climate change has not generally caused major species extinction. In other cases when temperatures have been much higher, species have generally flourished. Admittedly, previous warming has been quite a bit slower, so this is not a perfect analogue. But it’s at least some reason to think that a few degrees of warming doesn’t spell automatic doom.

4 Agriculture

One of the most concerning potential impacts of climate change is on agriculture. Some have forecasted that climate change would led to mass starvation on a global scale by depressing global crop yields. But Halstead doesn’t buy it.

Crop yields have been massively increasing globally and are continuing to increase. Thus, for climate change to cause dramatic mass starvation, it would have to offset the quite consistent trend of growth. This seems unlikely. Halstead notes “Calories per person have increased by 20% to 50% in almost all regions since 1961.”

There are three mechanisms by which climate change might decrease crop yields:

It will lead to greater thermal stress on livestock.

It will raise the risk of drought in various regions.

It will expose agricultural workers to greater heat stress and flood, making it harder for them to work.

However, there are two mechanisms by which it might increase crop yields:

Higher temperatures lead to a longer growing season.

Higher CO2 levels boost plant growth and speed up photosynthesis.

After reviewing a meta analysis by Challinor et al, as well as studies by Zhao et al, Jagermayer et al, Hasegawa et al, Tigchelaar et al, and Gaupp et al, Halstead estimates overall losses from thermal stress are likely to be, assuming 2 degrees of warming, a very tiny fraction of global crop production. One study’s rather representative guesses of losses from thermal stress caused by climate change was:

Wheat: 161,000 tonnes (or 0.02% of 2018 production)

Maize: 2,753,000 tonnes (or 0.3% of 2018 production)

Soybean: 265,000 tonnes (or 0.08% of 2018 production)

Halstead’s overall guess, after reviewing a bunch more studies, is that climate change will negatively impact food production somewhat but not disastrously. He concludes:

However, the existing evidence suggests that, with warming of 4°C, total global food production will very probably be higher than today. Even though food demand will rise this century, food consumption per person will also very probably be higher than today. There is some evidence that synchronised food production declines for some major food crops will increase, but these shocks will occur against a baseline in which food yields and production are much higher.

He estimates that even 9.5 degrees of warming—basically the highest reasonable level even if we burn through all fossil fuels—would not destroy global agriculture. There are no realistic scenarios by which climate change would majorly devastate global agriculture.

Overall, therefore, agricultural collapse from climate change is not likely to be a serious threat. While it provides some reason to try to mitigate climate change, it’s not likely to dramatically reshape the world.

5 Ecosystem collapse and threats to agriculture

One possible way that climate change could be an existential threat is if it collapses global ecosystems—and this destroys global agriculture. But Halstead argues that we are neither likely to see major species loss, nor global ecosystem collapse, nor would global ecosystem collapse eviscerate global agriculture.

Since 1500, about 900 recorded species have gone extinct. This means that present extinction rates are much higher than the natural background rate—as is true of most statistics in the world, Our World In Data has a nice chart illustrating this:

(I sometimes wonder whether there are any important statistical results that Our World In Data doesn’t have a cool chart illustrating).

But still, extinction has been slow enough that we’re quite far away from a mass extinction. It would take about 18,000 years of species loss at the level it’s been at since 1980 to reach a mass extinction. This gives us plenty of time to adapt. Now, this is probably an underestimate, because it ignores the number of species we’ve made endangered which haven’t yet gone extinct. But even taking into account more aggressive estimates, it will likely take thousands of years for us to trigger a mass extinction.

Halstead reviews a few studies estimating how much biodiversity loss climate change will cause, and estimates that there will not be a mass extinction in the near future. Thus, while species die-offs will continue, a mass extinction will not—at least not of the sort that could imperil agriculture.

In addition, most extinctions have been local and regional. But these cannot threaten agricultural yields. Halstead notes:

Following the discovery of the Hawaiian Islands by the Polynesians 1500 years ago, they eliminated so many species that even the decadal global extinction rate would have been exceptional. This has next to no bearing on the risk of ecological collapse outside of Hawaii. (It also did not cause catastrophic ecosystem collapse in Hawaii).

Thus, damage to biodiversity only threatens global civilisation if local biodiversity is declining in all regions.

However, most animal die-offs (95% since 2012) have been relegated to islands. For this reason, the kind of broad, system-wide collapse needed to imperil ecosystems is very unlikely. And most of this has been brought about by unregulated egg taking and hunting. Perhaps the sentence I found most surprising in the whole report is “The rate of continental species extinctions is close to one estimate of the ‘natural’ background rate.”

Though the world experienced centuries of deforestation, this trend has been reversed. Forest cover has been increasing for decades. Thus, annihilation of forests is unlikely to spark a major ecosystem collapse. And dire trends about biodiversity are largely overblown, having historically overestimated real losses. Mark Vellend notes:

Although it is declining globally, biodiversity is increasing or stable in many regions. This is because losses are being offset by increasing numbers of introduced or ‘invasive’ species. Various meta-analyses have shown that local species richness is fairly stable

…

Interestingly, our study was followed in quick succession by three other meta-analyses using independent data from different taxa and ecosystems showing essentially the same thing—no significant directional biodiversity change when averaged across many studies

Thus, there is unlikely to be massive species die-off or the sort of mass extinction some pessimists have forecasted.

Even if there is, it’s hard to see how this could threaten food production by very much. While the loss of pollinator species would decrease food yields, outside of that, it’s hard to see what could go so wrong. Our World In Data notes “studies suggest crop production would decline by around 5% in higher income countries, and 8% at low-to-middle incomes if pollinator insects vanished.” This would be bad, but not catastrophic.

Most likely there is no specific planetary boundary that would trigger mass ecosystem collapse. Instead, losses often beget more losses, but there’s no specific tipping point. Many of the richest countries in the world have the least intact biodiversity, and have not faced significant welfare declines as a result of that. Additional reasons to doubt that biodiversity collapse will destroy agricultural production include:

The area most likely to be richest in the future (China, the U.S., Europe) often have the least biodiversity. This is not what we’d expect if significant biodiversity correlated with flourishing.

Despite Eurasia—and especially England—having had enormous loss of biodiversity and mass ecosystem destruction for the last thousand years, agricultural production increased enormously. Mass ecosystem destruction did not lead to any major agricultural devastation. On the common view among environmentalists, that environmental degradation begets more environmental devastation until one has hit inevitable irreversible catastrophe, this is not what one would expect. If biodiversity loss is so deadly, it should have produced some serious harms by now.

Thus, the argument that climate change is an existential threat because it will undermine biodiversity is badly flawed. It relies on the following inference chain:

Global warming + habitat loss + human predation + pollution —> global species loss —> global ecosystem collapse —> global agricultural catastrophe.

Each step seems extremely doubtful. There will not be major global species loss, nor global ecosystem collapse, and if there were, it would not trigger an agricultural catastrophe.

6 Heat stress and sea level rise

Extreme temperatures make going outside deeply unpleasant. Often people die of heatstroke, and climate change clearly makes this worse. But how bad could this be?

One study—that was likely overly pessimistic—estimated that climate change could increase global deaths by around 1% (though even if this happened, it would be more than compensated for by other declines in mortality, so global mortality rates would keep droppping). This study also neglected various adaptation measures. It also relied on pretty low estimates of growth and high estimates of climate change. So near the highest end estimate is that climate change could cause around 5 million extra deaths per year.

While this is likely to be an overestimate, even if it’s only a million extra deaths a year, it means mitigating climate change is very important. Climate change doesn’t need to literally kill everyone to be major and bad.

Sea level will probably rise by about .75 meters in the next century. Now, while richer countries can generally mitigate against this—and around 30 million people live below sea level—poorer countries cannot. For this reason, large numbers of people in poor countries might be forced to leave. Probably a few hundred thousand people will be displaced annually, mostly in Asia.

In the much longer term, however, climate change will majorly boost sea levels. In 10,000 years time, sea level will be about 10 meters higher because of climate change. Thus, if you’re a longtermist, sea level rise is potentially pretty important. However, in the far future we are likely to have vastly greater prosperity. In any case, it’s not really an existential threat—just likely to cause massive human suffering.

7 Tipping points

Tipping points are mechanisms by which climate change begets more climate change. There are various mechanisms by which climate change will broach critical thresholds that make future climate change more severe. These include:

Permafrost release: permafrost is melted ice. It has a ton of carbon. When it melts, carbon is released, leading to more carbon being released. This effect is likely to be real but negligible compared to the direct effect of warming. It will raise temperatures by about .1 C on the high end.

Methane clathrates: clathrates are ice containing trapped methane. As these melt, methane is released. However, this is probably not a big risk for a few reasons. First, overall methane emissions from permafrost release have so far been minor. Second, most methane that is released doesn’t reach the atmosphere. Third, past warming in the paleoclimate record didn’t cause much methane release. Fourth, most experts seem to agree with this conclusion, and this tends to be the result of studies on the subject.

Amazon forest dieback: higher temperatures might lead to destruction of forests, thus releasing CO2. However, while early studies thought this could be significant, this fledgling consensus has been overturned, and the person who came up with the idea has said he’s now less concerned about it than he was originally. In fact, the negative effects of warming on forests could very well be overwhelmed by the positive effects on forests.

Boreal forest dieback: boreal forests are in the cold climate of high latitudes in the Norther Hemisphere. While the North is likely to experience diebacks, the South is likely to see expansions, so the IPCC thinks this is unlikely to be a major source of warming.

Collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation: AMOC is a system of wind currents that balances the climate by hot and cool air around. However, it is dependent on climatic conditions that are likely to be disrupted by climate change. If AMOC were shut down, there would be major cooling of the Northern Hemisphere and warming of the Southern Hemisphere. The North Atlantic might cool by a whopping 1-2 degrees. This is one of the more worrying tipping points, and it could severely impact weather conditions. If the AMOC collapsed, this would trigger major cooling in the Northern hemisphere which could be quite bad for global agriculture. The AMOC is unlikely to collapse entirely, but will likely be weakened somewhat. In expectation this is bad but not catastrophic.

West African Monsoon: a monsoon is a reversal of winds. It brings rainfall to West Africa and the Sahel. Overall though, climate change impacts the West African monsoon in various ways and the net effects are unclear but likely a bit bad because it will make weather patterns less predictable.

Indian Monsoons: same basic story.

Cloud feedbacks: these are likely the most worrying tipping points. Warming causes greater precipitation, leading to more clouds forming, which traps in more heat. Cloud feedbacks are the main reason why, in the past, the climate’s sensitivity to more warming have increased at higher temperatures (which means when the temperatures get higher, it becomes easier to get still higher temperatures). This is the most likely scenario for very extreme warming (~13 degrees), but is still extremely unlikely. While this kind of extreme warming would be unlikely to cause extinction—for similar high-temperature periods haven’t had mass extinctions—it could be really, really bad, and would pose non-trivial existential risks in the offchance it occurred.

For these reasons, while climate change will likely trigger more climate change, hothouse earth scenarios, where most warming is triggered by feedback loops, are quite unlikely. (Halstead also presents a bunch of reasons the hothouse earth scenario is bogus). Claims that feedback loops will snowball (bad analogy perhaps???) uncontrollably until the Earth becomes like Venus are not supported by most scientific evidence. If higher temperatures were capable of such incredible feats, we’d have become Venus during past eons when temperatures and CO2 levels were far higher. And even if such feedback mechanisms were put in place, such all water on Earth would be on track to all be lost to the atmosphere, it would take hundreds of millions of years for this process to be complete! During this time, there’d be plenty of time to adapt.

When estimating the existential risks from very extreme climatic scenarios, with around 10 degrees of warming, Halstead writes:

My back of the envelope model suggests that the chance of burning all the fossil fuels over all time is 1 in 500,000. If we burn all of the recoverable fossil fuels (3,000 GtC), there is a 1 in 6 chance of more than 9.6ºC. This suggests that over all time, the direct risk of extinction from climate change over all time is on the order of 1 in 3 million.

Thus, the only scenarios where tipping points are a serious existential threat is one that is very unlikely to arise in practice. The Earth will not become Venus.

8 Economic costs

By 2100, experts estimate GDP is likely to rise between 200% and 2000%. Over the course of the last century, per capita GDP rose about 450%—and overall GDP rose 1800%. In light of this, even if climate change is bad for the economy, it is unlikely to be catastrophic.

Halstead distinguishes two kinds of economic studies on climate damages:

Top down studies that attempt to estimate the effect of climate change on aggregate economic outcomes, like GDP, directly.

Bottom up studies that assess the effects of climate change on a specific economic sector or category of damages, which can then be aggregated across categories to estimate total damages.

Halstead then lists the results of the various bottom up studies that have been performed. They are broadly similar in holding climate change will reduce GDP by about 5%.

Halstead claims Takakura et al (2019) is the most reliable because it takes into account the greatest range of climate impacts, uses recent literature, and tries to account for non-climatic impacts. He then summarizes a range of top down studies:

Halstead then reviews a great many more studies of different kinds. Overall, he concludes that probably climate change will reduce GDP by around 5%. This seems pretty reasonable. Maybe it’s a bit more, e.g. 9%, but nothing close to the wholesale collapse of industrial civilization. Overall, the GDP will be far higher in a century than it is today, even if climate change makes it a few percentage points lower than it would have otherwise been.

9 Migration

One worry about climate change is that it will displace large numbers of people. A world of rising tensions, mass refugee crises, and displacement of a huge portion of the global population is likelier to succumb to existential catastrophe—or so many proponents of existential risk from climate change claim.

Right now about 23 million people are displaced by weather annually, and about 9 million are displaced by conflict and violence. Most of those displaced stay within their national borders. The number of new international migrants has been about 6 million per year for the last few decades.

Climate change will likely cause a few hundred thousand extra people to relocate annually, by raising the frequency of extreme heat. Taking into account flooding impact, probably it could well be a few million, though most of that will be internal displacement within a country. And while one particularly extreme study by Myers predicted hundreds of millions of refugees, this study used a totally loony methodology, assuming that anyone displaced in an area where climate change was even a partial factor was displaced because of climate change. Myers’ study is not taken seriously by the scholarly community. Halstead cites a battery of studies estimating the net impact on immigration and find the total number, and even the sign, are relativeley unclear:

Overall, climate change is likely to increase the number of migrants by about 10% at the high end, though even the direction of the effect is a bit unclear. Its net impact on the number of people internally displaced is pretty unclear, though it will displace sizeable numbers. The reason the impact is unclear is because those who are displaced often move nearer to the coasts which is made more difficult in a world with more climate change. This is, like the rest of its impacts, likely to be bad but not catastrophic.

10 Conflict

War is wrong—except for the second world war (fighting fascism, nothing wrong with that) and the American revolution and the Crimean war and the hundred years’ war. If climate change caused increasing conflict, especially between nuclear-armed powers, perhaps that could increase the chance of extinction.

Interestingly, the literature has generally found historically that cooling periods, not warming periods, are generally associated with international strife. This is somewhat evidentially significant, though we should be hesitant to extrapolate from history to the modern day. The fact that England in 1300 was more peaceful during warmer periods tells us something, but not a ton, about the impacts of climate change.

Fortunately, there have been more detailed analyses of modern-day studies. The IPCC’s takeaways from the studies that had been performed on the correlation, in the modern era, between conflict and wars was:

There’s little evidence linking climate change to interstate conflicts.

Climate change likely increases the odds of civil conflict—conflict within a nation. One major way it does this is by deleteriously affecting agriculture.

Water scarcity might affect civil conflict, though this is a bit unclear.

Climate change has been a small driver of civil conflict relative to other factors.

The future effect is relatively unclear.

Sakaguchi, Varughese, and Auld analyzed the existing literature on the impact of climate change on wars. In this context, a positive finding means one that finds that climate change increases the risk of war. The chart below shows their discovery—62.3% of studies find small increases in the risk of conflict as a result of climate change (though there is some substantial risk of selection bias).

Burke et al argue that when one looks only at the high quality studies performed on the subject, the relationship is much less noisy: climate change clearly boosts risks of conflict. However, this study has been subject to a great degree of criticism. Overall, Halstead concludes:

The Burke et al result is highly sensitive to the choice of time period and becomes much weaker or disappears after 2002, in a way that is inconsistent with one of Burke et al’s projections.

The Burke et al result is highly sensitive to the definition of civil war.

The Burke et al projection is one about severity, not onset, and the severity of conflicts is noisy and declining on the most plausible measures.

After reviewing other studies by Dell et al, Klomp and Bulte, and others, Halstead estimates that at the highest end, warming-related conflicts will cause roughly an extra 40,000 deaths by 2100. This is much less significant than most of the other harms of climate change. Everyone in the literature, even those with more pessimistic estimates, seems to agree that the impact of climate change on wars is small compared to other factors. Experts tend to think it maybe explains about 10% of the variation in conflicts at the high end.

Halstead then sets out to estimate the impact of climate change on great-power war. He thinks there are four mechanisms by which climate change might raise the risk of great-power war. But he doesn’t really buy any of them.

Causing water wars: in fact, wars over water are rare, and water scarcity is far more likely to lead to cooperation than conflict. One study notes “The only recorded incident of an outright war over water was 4500 years ago between two Mesopotamian city-states, Lagash and Umma.” In fact, the net effect of water scarcity on wars might go the other way: water scarcity usually fosters cooperation which raises the odds of peaceful resolutions to other conflicts. Overall, water scarcity making conflict more likely is probably bogus.

Imposing economic costs: As we’ve seen before, the economic costs from climate change are likely to be real but non-catastrophic. In addition, the association between economic growth and war is very unclear.

Raising the risk of civil conflict: This effect, as we’ve seen, is likely to be fairly negligible. Climate change will likely increase the risk of civil wars, but non-catastrophically. It is true, however, that greater civil instability raises the odds of broader regional and global wars.

Spurring mass migration: As already discussed, climate change is likely to have pretty limited impact on migration, and the net effect is somewhat unclear. There’s been no observed correlation between migration and international conflict.

The great-powers in the world are the U.S., China, and Russia. It’s very hard to see how hotter climates and more refugees would increase the odds of any of these countries fighting—especially because these hotter climates are concentrated on poorer countries that aren’t major international players. The only potential nuclear-armed conflict that climate change could seriously affect is between India and Pakistan, where, in both countries, a sizeable portion of people work in agriculture. Halstead then attempts to model risks quantitatively and finds that the risk of an existential catastrophe from great-power war caused by climate change is likely around 1 in 100,000 and very pessimistically nearer to 1⁄1,000.

Some have worried that higher temperatures could cause war by prompting individuals to be more prone to aggression. People act out more at higher temperatures. However, this effect size is very small. Halstead looks at a bunch of studies estimating this effect and concludes:

Overall, the effect of temperature on aggression seems like a negative effect of climate change, but one that is very small and will be swamped by the other determinants of aggression.

11 Conclusion

Climate change is real. It’s likely to be pretty bad. It will likely increase refugee flows, damage agriculture, make war a bit more common than it would otherwise be, and displace people by raising sea levels. There are also various worrying tipping points that could exacerbate its effects. Probably we’re in for about 2.7 degrees of warming. And while the sign of this effect is unclear, it’s also likely to increase wild animal suffering by staggering amounts.

But for all that, it’s not an existential threat. The world survived—and flourished—during past periods of warming. Each of the supposed mechanisms by which climate change might doom the world are fanciful and ridiculously unlikely. General ecosystem collapse, great-power war, conflicts over agriculture, mass refugee flows—none of these are likely results.

I would suggest that, at least in considering its human impacts, we should treat climate change a lot like we treat other global problems. Everyone agrees poverty is bad. In fact, poverty might raise the odds of conflict and extinction in various ways. But no one seriously proposes that poverty is an existential threat which we can only survive if we comprehensively address in the next five years by shutting down the global economy.

Those who claim climate change is likely to end the world have been involved in a kind of deeply pernicious climate misinformation that counterintuitively makes it harder to address climate change. We shouldn’t only be concerned about right-wing climate denial. It is not the only kind of climate misinformation, as Joseph Heath has pointed out. When people hear predictions of existential catastrophe, several bad things can happen:

It sounds crazy so they ignore it.

They conclude we’re all going to die, and get depressed, thinking that action is futile.

They think we’re all going to die, then wait a bit, see we don’t, and conclude it was all bullshit.

Each of these mean that climate change alarmism can set back climate progress. People often take existential risks from AI less seriously because a world where AI kills everyone is very different from the current world. If climate alarmists claim climate change will usher in an existential catastrophe that will bring about hell on Earth, this is just too different from the world that most people are used to. As a result, people don’t take seriously the very real death and suffering it will cause.

Much of the reason the environmentalist movement has burned through their credibility faster than humanity has burned through fossil fuels is they’ve repeatedly prophesied doom. Yet doom hasn’t come. As a result, people don’t take the next prediction of doom seriously.

Lastly, people become depressed and despondent, rather than serious activists for change when they think we’re all going to die. As Stephen Pinker notes, of those who think the world will end in a century, most of them agreed with the statement “The world’s future looks grim so we have to focus on looking after ourselves and those we love.” It’s not good psychologically for half of Americans to think that climate change will destroy the planet. Pinker, once again:

Few writers on technological risk give much thought to the cumulative psychological effects of the drumbeat of doom. As Elin Kelsey, an environmental communicator, points out, “We have media ratings to protect children from sex or violence in movies, but we think nothing of inviting a scientist into a second-grade classroom and telling the kids the planet is ruined. A quarter of [Australian] children are so troubled about the state of the world that they honestly believe it will come to an end before they get older.” According to recent polls, so do 15 per cent of people worldwide, and between a quarter and a third of Americans. In The Progress Paradox, the journalist Gregg Easterbrook suggests that a major reason that Americans are not happier, despite their rising objective fortunes, is “collapse anxiety”: the fear that civilization may implode and there’s nothing anyone can do about it.

Thus, climate alarmism of the sort that has spread like wildfire is immoral, false, and counterproductive. We are not doomed, and hyperbolic claims that we are stall real, pragmatic action on climate change. The dominant communications strategy of the modern environmental movement—find the most outrageously hyperbolic claim, quote it uncritically, ideally while overstating its conclusions—is a recipe for mass terror and alarmism but not for reasonable action. The truth is quite a bit more mundane: climate change is real and serious but not existential.

This seems right, and I’m glad to have book-length explanations and investigations of it. “Climate change is not an x-risk” is the kind of thing you can easily (and correctly) prove to yourself in a matter of hours, but it is surprisingly hard to get other people to both notice and admit it, especially en masse.

I will say this was not so clear 20+ years ago. Back then we hadn’t yet shown the runaway warming scenarios were unlikely, clean energy was far from cheap anywhere in the world, many industrial processes had no clear path to electrification, and affordable energy storage for homes/vehicles/grids or management of a high-renewables grid seemed like a distant dream to most who claimed to be experts. A lot of the messaging we still hear today was ossified based on that, which is a common problem for any situation where fast-moving tech frontiers can cause or fix medium to long term problems.

Ironically since the core topic is ecological, many people who are experts in a field have no sense of how different pieces of different systems interact beyond the obvious first order effects. They also tend to underestimate the long-term impact of sustained technological advancement. I think, to a significant degree, this is because forecasters tend to peg the modal scenario as the most defensible and therefore more likely. (Last year I heard a Bloomberg analyst basically declare this is what they do, and thankfully the audience of VCs seemed to understand this made the forecasts much less valuable). Problem is, most attempts to make large breakthrough advances fail, so this ensure the forecasts of tech progress are slow and incremental, but the reality is some percentage will succeed and accelerate things. (Also ironically, as I understand it, this pulled in the opposite direction for AI 2027, where the modal timeline was faster than what any of the authors endorsed on reflection, they just weren’t confident which hard steps would actually be major obstacles).

Personally I think the messaging really has been actively damaging to creating effective policy, and we’d have made even more progress reducing climate change with more honest, clear-headed, and strategically-sound activism. It’s an obvious lie/mistake, so those not already convinced look at the activists touting it and respond with some version of, “You’re clearly not worth listening to, and might be actively dangerous to leave unopposed.” And this is not specific to climate—it’s applicable to many other prominent/salient issues. This also makes it dramatically harder to discuss actual x-risks in ways that get people to pay attention, which I think is a significant part of why AI x-risk gets immediately downgraded to things like job loss in many peoples’ minds.

How do you do that? I’ve spent several hours researching the topic and I’m still not convinced, but I think there’s a lot I’m still missing, too.

My current thinking is

Existential risk from climate change is not greater than 1%, because if it were, climate models would show a noticeable probability of extinction-level outcomes.

But I can’t confidently say that existential risk is less than 0.1% because the assumptions of climate models may break down when you get into tail outcomes, and our understanding of climate science isn’t robust enough to strongly rule out those tail outcomes.

Ok, fair, ‘prove’ is a strong word and we can have different opinions on both the probability estimate of climate-induced-extinction and the threshold for that probability being low enough to count as ‘not an x-risk.’

In order to actually wipe out all humanity, such that there were no residual populations able to hang on long enough to recover and rebuild, the climate would need to change faster than any human population, anywhere in the world, could adapt or invent solutions. Even if life sucked for a decade or a millennium, or if there were only 10k of us left in a few enclaves worldwide, that could still avert extinction. Considering the range of environments humans can survive in today, that’s an extremely high bar. Considering the pace of technological advance we have been ability to achieve under duress, it’s even higher. Climate change could cause catastrophic events that are extremely disruptive to huge numbers of people. It could, over the scale of decades, make it much harder for the world to support the current population of humans using current technology. It could force mass migrations over decades of large numbers of people. But IMO, none of those are enough to wipe out all of humanity faster than we could develop solutions for some subset of us to survive.

It could, however, trigger resource wars that increase other forms of x-risk, like nuclear and biological warfare. I wasn’t counting that as climate change x-risk in my accounting, not sure if you were.

I directionally agree but I don’t think that’s the sort of reasoning in which you can be >99.9% confident.

I’m also concerned about runaway warming making earth uninhabitable. Climate models suggest that won’t happen but Halstead (implicitly) expects a <0.001% chance of runaway warming which seems hard to justify to me.

I also don’t think I would estimate anywhere near that low, especially since the risk is spread over many years. On a per-year basis that is near or below asteroid x-risk level. 99.9 to 99.99 seems like the right range to me.

Are you saying 99.9 to 99.99 per year, or total?

Total, but I don’t think the difference is as large as it might seem. Fundamentally, barring another collapse that stops our advancement, I don’t think we have more than about a century, at the high end, before we reach a point technologically where we’re no longer inescapably dependent on the climate for our survival. Which means almost all my probability for how climate could cause human extinction involves something drastic happening within the next handful of decades.

Most of that remaining probability looks something like “We were wrong to reject the methane clathrate gun hypothesis, and also the older, higher estimates of how much carbon they contain were right. There really can be catastrophic release over just a few years that kills all life in the seas and makes the world essentially jump forward several hundred years’ worth of carbon emissions all at once.” There are other catastrophic events that could happen—sudden collapse of the west antarctic ice sheet, rapid shutdown of the gulf stream—but none I know of that would literally render the planet uninhabitable or unable to support enough humans to eventually recover.

Ok, it sounds like we agree on pretty much everything except what it means for something to “be an existential risk”. I think 0.01% still counts as a risk worth worrying about (or it would, if AI x-risk weren’t multiple orders of magnitude higher).

Why not read and review the IPCC report? I am confused by why this seems to not be the most popular recommendation for people on this forum who want to understand the most up-to-date scientific consensus on climate change risk. It’s written by an international community of scientists, it’s very accessible with further higher-level overviews aimed at decision-makers and the broader public, all claims include an estimated level of uncertainty (and are very conservative) and you can follow the citations for any particular claim made. The website is great, the writing and figures are very clear.

I would not recommend Halstead’s report to someone trying to learn more about this topic. His summary of the research is not great in my opinion. This is a huge topic that touches many fields and even an expert in one of these research areas would struggle to put together a good overview of all of the others. But as I skimmed through this I noticed a few takes that are quite...off, and papers that I know to be outdated or widely considered erroneous being used as evidence for claims.

Some more context for those interested: Climate impact research is almost never looking at ‘worst case’ scenarios, but plausible outcomes. Papers looking at projections with high warming levels are often older, when it was less certain that much action would be taken to curb emissions, and very high warming scenarios seemed more likely. Also, climate science has very different confidence levels than climate impact research. Climate science is heavily based on physics, and doesn’t have to deal with the messiness of animal and human biology and behaviours and so on. Impact research is much murkier, as it depends on accurate understanding of the way animals, plants and humans respond to conditions that are outside of what has previously been observed, and often cannot be studied in RCTs. A lack of scientific consensus that extreme impacts are likely should not be mistaken for the presence of scientific consensus that extreme impacts are unlikely.

Do you think you can learn something useful about existential risk from reading the IPCC report?

FWIW I only briefly looked at the latest report but from what I saw, it seemed hard to learn anything about existential risk from it, except for some obvious things like “humans will not go extinct in the median outcome”. I didn’t see any direct references to human extinction in the report, nor any references to runaway warming.

This equivocates between Venusian conditions and “Hothouse Earth.” “Hothouse Earth” merely refers to the melting of the ice caps, a situation that the Earth has experienced, and which is thus definitely possible, but which is not an x-risk.

Values difference rather than an error? I don’t imagine that “preventing wild animal suffering” ranks particularly highly on the list of things “those on the right” are concerned with. Or anyone who’s close to mainstream politics, really.

I agree entirely with the core claims of “climate change is not a credible x-risk”, “impacts of climate change are vastly overstated by mainstream media” and “the mainstream discourse around climate change is incredibly harmful”. Doomerism and anxiety help no one—and deceiving people into taking climate action trades off your future credibility.

I’ve done this kind of evaluation before, just with much less rigor, and came to similar conclusions: anthropogenic climate change is very much real, but extinction risk from climate change isn’t. Climate change still has mundane harms, and is likely to be worth fighting anyway.

I haven’t seen that discussed much, and I’ve been thinking of making an LW post to put that out there myself. Good to see someone else has.

The only credible “kill chain” for mass causalities from <3C climate change that I could find was “temperature increases → agricultural failures → famine”. Partially mitigated by agricultural adaptations and general agricultural productivity gains—but not every country can afford complex infrastructure for agricultural adaptation, and there are countries that are both dangerously poor and lack the infrastructure and institutions for effective food distribution. So local agricultural failures coupled with a global spike in food prices could cause a lot of death and suffering.

Which may be a real pathway to a death toll of up to 600 million, over decades—a noticeable uptick from the status quo of ~9 million hunger-related deaths per year.

Survivorship bias makes us underestimate climate risks (but not most anthropogenic risks) as well as climate fragility.