The recent banality of rationality (and effective altruism)

[Neurotic status: Until recently, I’ve felt entirely comfortable telling friends, family, and co-workers that I’m a rationalist (or an aspiring rationalist)—that it wouldn’t out-group me among them, or if it did, it was probably worth being out-grouped over. I will happily continue to use Bayesian reasoning, but I can’t rep the label “IRL” right now. The distal reasons for this change are (1) I believe rationalism and effective altruism as movements are losing their ability to self-correct, (2) I’m not in a position to help fix (1). I hope this is temporary or that I’m wrong. I started writing last week, and there may have been development since then that I missed. I love you all like a milkshake.

I avoided using easily searchable terms below to keep out the riffraff.]

I started rewatching Deadwood last week. I previously finished it sometime around 2008. It was the right amount of time to wait. I’ve forgotten enough that it’s entertaining again.

Spoilers ahead

I was more impressed than I remembered with the first trial of Jack McCall as portrayed in the series. In real life, there was a Jack McCall who killed Wild Bill Hickok while he was playing poker, and there is some evidence that Wild Bill was holding “Aces and Eights” when Jack shot him in Deadwood.

Doing some cursory searches, the portrayal of Jack McCall’s first trial in the series isn’t entirely historically accurate, and the series, in general, elides uncomfortable truths about “settler isopolities” (as both IMDB trivia and scholarly literature attest to). But the gist and broad strokes appear correct enough for the scope of the point I’m trying to make.

At the time of this shooting, Deadwood was an illegal settlement on land designated for the Lakota. Meaning there was no formal legal authority for adjudicating such crimes.

In the absence of proper authority, the inhabitants of the illegal settlement (camp) self-organize and form a court to conduct a trial. They create a process to select jurors, a judge, a defense lawyer, and a prosecution lawyer. They decide on a venue and date for the trial. Then the trial happens. Voilà!

The Deadwooders (Deadwoodans? Deadwoodites? Deadwoodganders?) found themselves in an unprecedented circumstance. Yet, they devised a viable plan and executed it, maintaining order in the camp. I find this to be inspirational and embarrassing. What happened to our capacity for spontaneous cooperation?

Let us calculate!

Two score and three years ago, I signed up to take Philosophy of Logic. The Philosophy Department was fighting over which faculty member had to teach it that year, and by the first day of class. A professor volunteered to teach just the first day and give an introduction to the topic, taking pains to clarify he probably wouldn’t be involved in the rest of the course. I wish I could remember his name because his introductory lecture changed my worldview. Though, I dropped it that semester to take it later with an instructor who thought teaching Logic was less of a chore and more of a pleasure. I know. Cool story, right? Let me get to the point.

His lecture was similar to what Audrey Borowski writes in a blog post about Gottfried Leibniz and the notion that reasoning and epistemology could be formalized to a point where the moment a dispute becomes heated, for example, a cool-headed philosopher could interject a phrase and all the parties involved would realize “oh, we can just calculate the answer!”

Crucially, Leibniz had concerned himself with the formalization and the mechanization of the thought process either through the invention of actual calculating machines or the introduction of a universal symbolic language – his so-called ‘Universal characteristic’– which relied purely on logical operations. Ideally, this would form the basis for a general science (mathesis universalis). According to this scheme, all disputes would be ended by the simple imperative ‘Gentlemen, let us calculate!’.

While I sometimes get into heated disputes, I don’t enjoy the disputes or how I feel after them. I like this idea of quickly and logically resolving them so that the conflict, at least, is no longer so heated. It also has the happy side-effect of making the parties involved better attuned to reality. I was impressed that Rational Animations introduced their video on Bayesianism with that same story. In the current year, Bayesianism is about as close as you can get to what Leibniz was after here.

I’d have to imagine nearly every self-describing rationalist or effective altruist groks this. More than that, many (or most) have read about the Robber’s Cave, the Blues and the Greens, The Toxoplasma of Rage, I Can Tolerate Anything Except The Out Group, and much of the other wisdom on related topics from Dan Kahan to Danny Kahneman.

The recent banality

It wasn’t long ago that rationalists could brag about beating the experts. Lately, despite being armed to the teeth with the knowledge necessary to deal with unprecedented circumstances and settle heated in-group disputes gracefully, our performance is mediocre in both cases.

Like others, I see this month’s events splitting us into tribal groups. But I see this as regrettable subpar behavior for us rather than a victim of circumstance kind of thing. The infighting and splitting are what I’d expect to happen in other organizations when something controversial occurs. It would be average and, to a degree, understandable “over there.” In our case, we should be uniquely equipped to avoid it. What went wrong?

I saw many dispositive takes in November along the lines of “no one could have seen this coming.” Or, more ironically, “the experts (that we so often outperform) couldn’t have predicted this, so we shouldn’t feel that bad.”

I felt like a question would be the most appropriate response there. “How were our models deficient in such a way that this was not included or assigned a negligible probability?” Maybe there were genuine attempts (not just hand-wringing) at that discussion that I missed? I’m happy to be wrong if that’s the case.

There was an excellent discussion about November and related implications on The Bayesian Conspiracy podcast (episode 175), except for a few seconds where it managed to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory. Towards the end of a lengthy back-and-forth about effective altruism as a movement, the conversation goes like so (sorry if I got the names mixed up).

Steven: So you think self-aggrandizing sociopaths [who are in EA] suck?

David: Yes

Steven: And I agree with you. That has nothing to do with EA aside from [the fact that] they have as many of those as any organization does.

I saw a lot of this “don’t hate on us; we’re average” in various forms. The entire point here is that we’re developing ways of thinking and working that should allow us to perform above average. If that’s not happening, and we don’t particularly care that it’s not, what are we doing here? I’d like to hear, “don’t hate on us; we’re learning and adapting.”

I see that the early January and November responses have different anti-patterns. I haven’t been following the fallout of the second January response close enough to comment specifically.

January: lack of punctuated synthesis, dialectic health

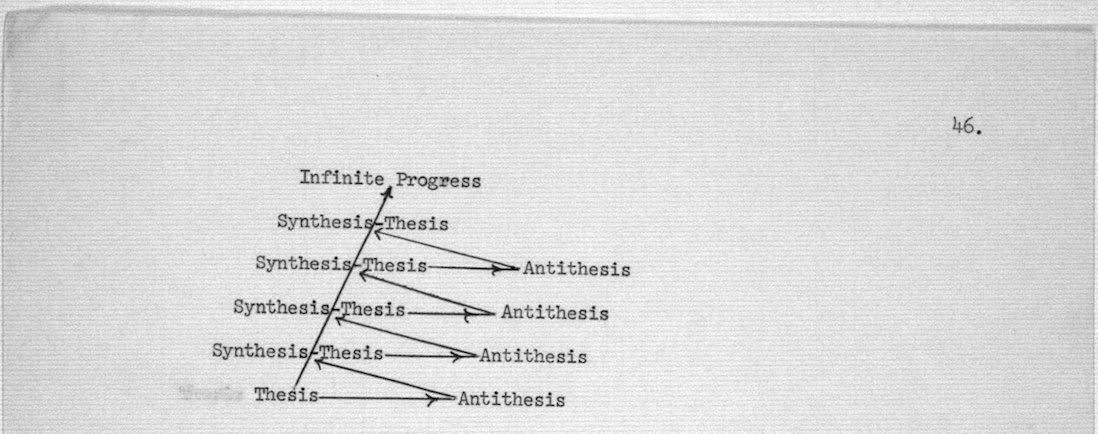

“Let us calculate!” ideally should mean that a group of such like-minded people, while not always in a synthesis state, are always trying to find our way to the next synthesis. In a meta sense, I’m not particularly concerned with what takes someone brings to a forum (assuming the forum keeps a balance of openness and moderation). I’m more concerned with people leaving a discussion or lingering in it without coming closer to a synthesis.

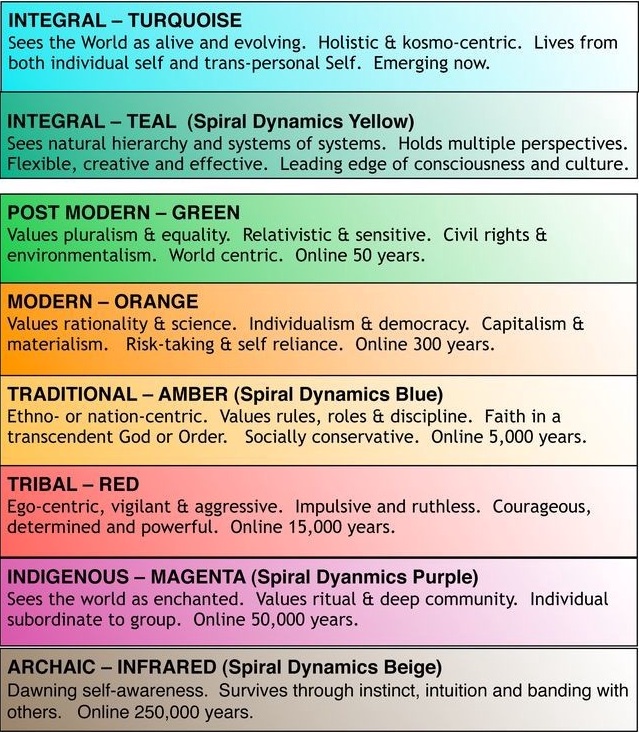

I’m not here to stan for Integral, and I’m not an expert in it. I just want to add a bit more color (no pun intended) to the description of dialectic health, or lack thereof. I’m used to seeing a lot of Teal/Yellow here. Meaning systems thinking types that can model multiple perspectives. No one can maintain that 100% of the time, but recently I have seen people retreating to Green or Orange and then sometimes all the way down to Red.

I will stan for Transactional Analysis, although I get it if this triggers your woo-allergies. It is an apt but not a perfect analogy here. It applies to the extent that finding yourself or your interlocutors exclusively in Critical Parent, Nurturing Parent or Adaptive Child states is a sign that synthesis is probably getting further away—or you’re heading towards an unfortunate “synthesis.” If the Critical Parents win, it will be some fascist letter-of-the-law rule-following. If the Nurturing Parents win, the synthesis position will sound like it was written on molly. If the Adaptive Children win, the synthesis will be like eating a box of cake mix while binge-watching anime. (Blindboy’s episodes Creaking Ditch Pigeon and Rectum Pen Pals are very good on this topic, although misleadingly named, probably named while the author was in Free Child).

The recent dialectic flavors have hints of Manichaeism (there is the good side, and then there are the new members of the out-group), Discordianism (just confused schism-seeking, not the fun quirkiness) and “anti-Seldonism.” I made up that last term, but it’s related to a passage in Asimov’s Second Foundation.

So he [Hari Seldon] created his Foundations according to the laws of psychohistory, but who knew better than he that even those laws were relative. He never created a finished product. Finished products are for decadent minds. His was an evolving mechanism and the Second Foundation was the instrument of that evolution.

I mean anti-Seldonism in the sense that we’re allowing ourselves to be argued into a corner where we unintentionally present rationalism or effective altruism like finished products, both in philosophy and in practice.

November: HUGLAGHALGHALGHAL Deference Fields

[Internal dialogue regarding all-caps term use: Are there less noisy concepts that combine having sex and taking drugs? Partying? Nah. I’m thinking about drugs that brighten people’s days in addition to the ones that spice up their nights. I could pick a sexy druggy god like Dionysus or Xōchipilli? Ow! I could call them Dionysian Deference Fields. I like the alliteration, but Dionysian is maybe too loaded a term. Like, I don’t mean it as contrasted to Apollonian. HUGLAGHALGHALGHAL it is, though operationally defined to include all varieties of sex or taking drugs (not necessarily at the same time).]

Without being judgy, I want to talk about how I saw people not talk about HUGLAGHALGHALGHAL in a way that circumspectly explored its potential as a distal causal factor in the events of November. It’s unclear to me if it was common or rare among our cultural compatriots in 242. For my point, its amount and frequency are not particularly relevant.

Lifestyle practices in 242 (the ones often covered in the news media) are practices that many of us also follow or have sympathy for. As relevant here, many of us are neurodivergent or are strong advocates of better living through chemistry. It’s common for us to take prescriptions or supplements for that purpose. Also relevant, many of us find ourselves interested in non-traditional relationships.

Readers are likely familiar with Ugh Fields and Somebody Else’s Problem (SEP) Fields.

This field operates when: (1) There is HUGLAGHALGHALGHAL common in our culture, but that is considered deviant in mainstream culture, for which we, understandably, would like not to have generally associated with a propensity for wrongdoing. (2) Wrongdoing occurs (or is alleged), and the would-be wrongdoers also HUGLAGHALGHALGHAL in ways familiar to us, so we jump to diminish the possibility of any causal connection between the two.

How could any 242 HUGLAGHALGHALGHAL have been a causal factor?

I will self-disclose a bit here, but as an appeal to what I believe are pervasive experiences in a way that makes this possibility clear.

I have a shifting stack of drugs (Rxs and supplements) I’ve taken for 20+ years to pass as gracefully as possible amongst neurotypicals. That stack includes an ADHD-treating stimulant. Even with an excellent psychiatrist’s help, managing these is not easy. When the stack needs to adapt to my circumstances, it often impacts my work performance. If I’m not careful, that can have real consequences.

When Scott says (paraphrasing hopefully fairly) he thinks it’s unlikely that a dopaminergic drug shifting complicated risk curves in the brain was particularly relevant, that’s saying too much and too little. Having been an end-user of psychopharmacology for two score and more, if I could go back in time, the question I’d ask is more general. “Are you responsibly managing your medication/supplements at a level commiserate to the vast amounts of power you wield?” The point is that there are so many ways that can become a problem, beyond what Scott discussed. Even a small problem in a position as powerful as that could have tsunami-like ripple effects.

I’m in a traditional marriage now. Prior to being married, nearly all of my romantic life had been as a serial monogamist or dating with the goal of serial monogamy. However, the human emotions I experienced during those relationships are close (if not identical) to the emotions humans in non-monogamous relationships experience. The highs and lows in my relationships always affected my work or scholastic performance. I don’t see why that would be fundamentally different for people in 242, regardless of relationship style.

In Zvi’s writeup, he mentions the potential of romantic entanglements but concludes, “I do not see this as central.” (point 43). He may have information I don’t that tells him those are not central. Failing that, I have decades of experience being a human in and out of romantic relationships. That experience tells me the potential significance of those entanglements (or recent disentanglements) was dismissed prematurely.

If there’s anything that in the fullness of time could be a part of a “lessons learned” there, it need not mention non-monogamy. It could focus on managing the complications of people with dual roles in your life. For example, if someone is your romantic partner and the CEO of a company with whom you have close financial ties. Again, with a time machine, I would ask, “are you managing the blended relationships in your company at a level commiserate with the vast amounts of wealth entrusted in it?”

A guess

It’s been an ongoing revelation as to how much money is invested in offshoots of ideas created or popularized by rationalists and effective altruists. This money could be a double-edged sword. Perhaps in-group status has a lot to do with one’s likelihood of getting into a position to receive some of that investment. Maybe people’s actions are becoming more instrumentally driven to improve the optics of their position. That could make it difficult to agree on optimal courses of action and relevant object-level facts.

In Deadwood, almost the reverse was true. If the camp wasn’t functioning with a minimum level of harmony, order and fairness, it put everyone’s ventures at risk. So while there was a lot of politics, it was mostly legible and aligned on “big picture stuff.”

Picture Deadwood, instead, where the predominant economic driver is a large amount of investment money hovering outside the camp. Every Deadwooder is trying to look more popular than other Deadwooders to prove themselves more deserving of investment. New people come to the camp expecting a familiar set of norms and are surprised to find themselves entangled in another’s plot that uses their noob naiveté against them to advance the plotter’s ambitions.

If Cathy Newman is reading, I’m not saying rationalists should organize themselves along the lines of illegal American frontier mining settlements. I’m also not saying we should have self-organized trials.

Why not be the signal you want to hear in the noise?

In an autoplastic sense, I would if I could figure out a way to do that. This is becoming a sport for people who are sufficiently able to prevent/weather any unexpected and undesirable outcomes. I fully admit I’m not there and envious of people who are.

I also don’t have a silver bullet to offer here, but I have two thoughts.

Quality is altruism, earning to give asymptotically approaches rent-seeking

If we’re going to say preventing disasters is altruism, then preventing things like the last FAA outage is for sure altruism. In that case, it could have been prevented with better engineering. You can prevent disasters like that just by doing quality work at your job. This is true for everyone, not just people in tech and manufacturing. Attention to quality in every line of work will help prevent disasters at some scale. If you want to double down, read up on W. Edwards Deming, Joseph M. Juran and Kaizen. Think of all the quality engineering in cars, power plants, airplanes, food, drugs, medical appliances, etc. How many lives has that saved or improved the quality of, compared to a universe where it was all sloppy work?

Imagine you want to make a lot of money as quickly as possible so you can give some away. You make a lot of money successfully doing crypto market arbitrage, and now you have a lot of money to give to charities. Then you move on to other horizons in quantitive trading. What value are you adding? Investopedia says normalizing prices and providing the market with liquidity. I will grant it adds some non-zero value to the world. Playing that game seems to create a lot of disasters, and the value to me feels very abstract.

My spidey-sense tells me that some quant type person could explain why I’m not giving putative market operational benefits from arbitrage nearly enough credit.

If such a person is reading, this is what you sound like to me.

Quant: I like the Super Bowl, and I have all these complicated side bets on it, but it’s so inefficient. We should replace the Super Bowl stadium with a random number generator that adds a little noise to football outcome distributions and simulates the game. Then we could have as many Super Bowls as we want, and we could all make more bets. We’ll make sure all the gamblers understanding earning to give, so more money will go to charity. And when people lose, there will be all these charities to help them.

Then we can have an economy that’s all random number generators, bets on random number generators, bets on the bets on random number generators, bets on the bets on the bets on random number generators… and charities.

Fire Retrain all of your philosophers and reduce your scope

The goals of EA’s notable projects are pretty straightforward, and you don’t need a lot of philosophical overhead to make them happen or understand them. Many problems are caused by people tripping over philosophy that doesn’t need to be there.

Reading EA’s About page, the scope is massive: “find the best ways to help others, and put them into practice.” Let’s say I started an organization whose stated purpose was “find all of the bad things that can happen to people and try to prevent them from happening.” Is there much daylight between those two scope statements? Just whatever is bad that can’t be helped? We’re the kind of people who talk about curing death. So, no difference?

EA should focus on its core strengths. You can’t fix everything. Keep about the five most successful or high priority projects (like for sure AI alignment and GiveWell) under your wing. If you don’t want to give up on something, spin it off into another organization. If you want to discuss intersections at health economics, utilitarianism, and charity, for example, that volatility should probably be far away and under a different name.

It feels like there is something interesting in this post, but I found it scattered and meandering to the point of unreadability, sadly.

I too tried to read this post and couldn’t figure out what its point was most of the time.

The author is going out of his way to not say whatever he is saying. He is writing in allusions that will only make sense to people closely connected to whatever he’s talking about. “242” → Bahamas → FTX is clear enough, but I don’t know what else I’m not getting and it’s not worth the effort to me to find out.

Presumably this is the intended effect.

Was trying not to specifically mention FTX, Nick Bostrom or Max Tegmark. I wanted to keep the audience to people who were familiar with it and not people Googling the topics who were off-forum and not EA or rationalist types.

I tried to make that clear in the introduction.

Huh… thought I would get disagreement, but not for that reason. Thanks for the feedback. I was trying not to use terms that would appear in searches like FTX, Nick Bostrom or Max Tegmark. I did link to relevant posts where I thought it would be unclear.

IMO, the series of crises in the EA movement is at partly related to the fact that the EA movement is obviously having issues.

With that stated, I think EA probably can’t do well for a very basic reason: The idea that you can improve or harm society’s preferences, because there are no preferences of society, since it doesn’t exist. Thus I think EA is trying to do an impossible goal.

This is explored in the post below on Thatcher’s Axiom:

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/YYuB8w4nrfWmLzNob/thatcher-s-axiom

IMO, I think the rationality project/LW is handling these crises far better than EA is doing.

I’m not really sure if they’re separable at this point? There’s so much overlap and cross-posting, it seems like they have the same blood supply.