Worrying less about acausal extortion

I’ve wanted a good version of this post to exist for awhile. I’m not sure how to write that post. But here’s a okay-ish first draft, which seemed hopefully better than nothing. I’ve made it possible for anyone to write comments on the LessWrong doc editor version of the post, so if you have ideas for how to improve it you can leave line-notes here.

Once a month or so, the Lesswrong mods get a new user who’s worried about Roko’s basilisk, or other forms of acausal extortion. They write a post discussing their worries. In the past, they’d often get comments explaining “Here’s why you don’t need to be worried about acausal exortion”, but then respond with “but, what about this edge case you didn’t specifically address?”.

And this is a fairly sad situation – acausal trade/exortion is a bit confusing, and there are few places on the internet where people are knowledgeable enough to really explain it. But, my experience from talking to people worried about this is that no amount of explanation is really satisfying. They’re left with a lingering “but, what if I didn’t understand this properly and I’m still vulnerable?” and they keep looking to understand things better.

My impression is that often, they’re caught in an anxiety loop that wants to reinforce itself, and the act of worrying about it mostly encourages that anxiety loop to keep going rather than reassure it. I don’t think the winning move here looks like “thoroughly understand the situation until you are no longer anxious”. I think the winning move is more like “find something else to think about that is interesting so that the loop can wind itself down” or “I dunno, go outside and get some fresh air and take some deep breaths.”

I don’t actually know what empirically works. (I’m interested in comments from anyone who was worried about acausal extortion and who eventually stopped being worried, who can talk about their experience)

It seemed good to have an FAQ that at least covered some basics.

So:

Should I worry about Roko’s Basilisk or other acausal extortion stuff?

My short answer is “no”, but I want to acknowledge this is a kind of tricky epistemic puzzle for the sort of person I’m imagining reading this post.

If you’ve been think about acausal extortion for over a week and a really distressed about it, I think you should have a few hypotheses, which might include:

Acausal extortion is unlikely

Acausal extortion is likely, and there are practical actions you can take to prevent it

Acausal extortion is likely, but there aren’t practical actions you can take to prevent it

Acausal extortion is likely, but thinking about it is most likely to make you more vulnerable rather than less.

I think you should also have some hypotheses about your motivations:

You are thinking about this because it’s a legitimately important question that you’re responding proportionately to.

You’re thinking about it because it’s philosophically interesting and you’re just curious/interested in the topic.

You are thinking about this because it seemed scary, and somewhat philosophically confusing, and your brain ended up in an anxiety spiral which is now not very entangled with the original goal of “figure out if there is something important here.”

You are thinking about this because your body/brain is generally predisposed towards anxiety right now for an unrelated reason, and you are latching onto acausal extortion as a post-hoc thing to justify the anxiety.

Note that if you’re not feeling distressed, and are feeling more like “this is an interesting question”, I think you’re more likely in motivation #1 or #2. This post is mostly targeted towards people who are feeling scared and anxious about it.

If you’re distressed about it, I happen to think you’re more likely in motivation-world #3 or #4 than #1 or #2. But, one of the whole problems here is that it’s hard to tell from the inside.

Regardless, when looking at the brute “what does the territory look like here?” question of “is acausal extortion likely, and are there practical things I could do about it?”, two things that seem important to me are:

Acausal extortion really just doesn’t work on humans, for a variety of reasons.

Even if there were edge cases that somehow were risky… thinking about them would presumably be harmful rather than helpful.

Either it’s true that acausal trade is risky (and so thinking about it is dangerous, and you shouldn’t do it), or it’s not, so worrying about it is mostly a waste of time.

I realize it’s generally hard to follow advice of the form “try not to think about X.” But sometimes “just try not to think about X” is really the best option. Meanwhile, I am pretty confident that Roko’s basilisk or similar acausal threats don’t actually work on humans.

Okay, but, remind me why this doesn’t work on humans?

I think Eliezer’s statement on this from 2014 is still a fairly good explanation.

What’s the truth about Roko’s Basilisk? The truth is that making something like this “work”, in the sense of managing to think a thought that would actually give future superintelligences an incentive to hurt you, would require overcoming what seem to me like some pretty huge obstacles.

The most blatant obstacle to Roko’s Basilisk is, intuitively, that there’s no incentive for a future agent to follow through with the threat in the future, because by doing so it just expends resources at no gain to itself. We can formalize that using classical causal decision theory, which is the academically standard decision theory: following through on a blackmail threat, in the future after the past has already taken place, cannot (from the blackmailing agent’s perspective) be the physical cause of improved outcomes in the past, because the future cannot be the cause of the past.

But classical causal decision theory isn’t the only decision theory that has ever been invented, and if you were to read up on the academic literature, you would find a lot of challenges to the assertion that, e.g., two rational agents always defect against each other in the one-shot Prisoner’s Dilemma.

One of those challenges was a theory of my own invention, which is why this whole fiasco took place on LessWrong.com in the first place. (I feel rather like the speaker of that ancient quote, “All my father ever wanted was to make a toaster you could really set the darkness on, and you perverted his work into these horrible machines!”) But there have actually been a lot of challenges like that in the literature, not just mine, as anyone actually investigating would have discovered. Lots of people are uncomfortable with the notion that rational agents always defect in the one-shot Prisoner’s Dilemma. And if you formalize blackmail, including this case of blackmail, the same way, then most challenges to mutual defection in the Prisoner’s Dilemma are also implicitly challenges to the first obvious reason why Roko’s Basilisk would never work.

But there are also other obstacles. The decision theory I proposed back in the day says that you have to know certain things about the other agent in order to achieve mutual cooperation in the Prisoner’s Dilemma, and that’s with both parties trying to set up a situation which leads to mutual cooperation instead of mutual defection. As I presently understand the situation, there is literally nobody on Earth, including me, who has the knowledge needed to set themselves up to be blackmailed if they were deliberately trying to make that happen.

Any potentially blackmailing AI would much prefer to have you believe that it is blackmailing you, without actually expending resources on following through with the blackmail, insofar as they think they can exert any control on you at all via an exotic decision theory. Just like in the one-shot Prisoner’s Dilemma, the “ideal” outcome is for the other player to believe you are modeling them and will cooperate if and only if they cooperate, and so they cooperate, but then actually you just defect anyway. For the other player to be confident this will not happen in the Prisoner’s Dilemma, for them to expect you not to sneakily defect anyway, they must have some very strong knowledge about you. In the case of Roko’s Basilisk, “defection” corresponds to not actually torturing anyone, not expending resources on that, and just letting them believe that you will blackmail them. Two AI agents with sufficiently strong knowledge of each other, and heavily motivated to achieve mutual cooperation on the Prisoner’s Dilemma, might be able to overcome this obstacle and cooperate with confidence. But why would you put in that degree of effort — if you even could, which I don’t think you as a human can — in order to give a blackmailing agent an incentive to actually carry through on its threats?

I have written the above with some reluctance, because even if I don’t yet see a way to repair this obstacle myself, somebody else might see how to repair it now that I’ve said what it is. Which is not a good general procedure for handling infohazards; people with expert knowledge on them should, obviously, as a matter of professional ethics, just never discuss them at all, including describing why a particular proposal doesn’t work, just in case there’s some unforeseen clever way to repair the proposal. There are other obstacles here which I am not discussing, just in case the logic I described above has a flaw. Nonetheless, so far as I know, Roko’s Basilisk does not work, nobody has actually been bitten by it, and everything I have done was in the service of what I thought was the obvious Good General Procedure for Handling Potential Infohazards.

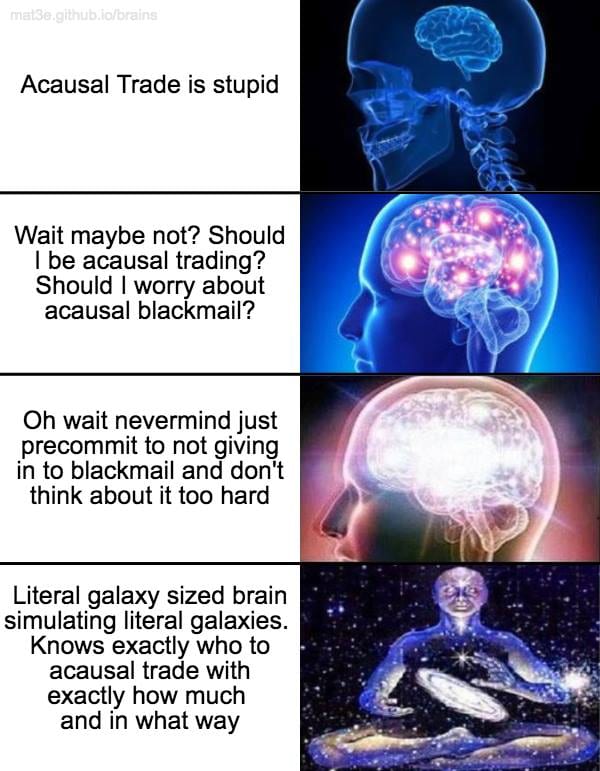

Galaxy Brained Solutions

People talk about galaxy brains a lot in internet meme groups. I want to spell out a bit what galaxy brain means, because it’s relevant here:

Galaxy-brained means that you have an actual galaxy worth of resources, taking the energy from 100 billion stars, converting that into computations, and then using those computations to solve unimaginably complex problems with unimaginably complex solutions.

A human is not a galaxy brain. When humans try to do galaxy brained thinking, they mostly do stupid things – that’s why the meme is funny. Overly complicated plans usually don’t work. Sometimes they do, but in those cases it’s not a literally a galaxy-brained-idea, it’s just “a more-complicated-than-usual human-sized-brain-idea”.

Simulating an AI in high enough resolution to actually make a conditional, specific deal with it is the sort of thing that requires an actually huge brain. A human vaguely imagining a hypothetical future AI does not count.

I don’t know whether you need a literal galaxy of resources, but I’d probably want at least a planet-sized brain, and have spent a lot of time thinking about moral philosophy and rationality and whatnot. I’d want to be very confident in what I was doing, before simulating an AI that might try to blackmail me. And by then, I’d probably also just know how to make productive acausal trades with alien intelligences that that won’t try to extort me.

Meanwhile, you do not have a galaxy sized brain.

You cannot actually hurt yourself in this way.

Acausal Normalcy

That all said, Andrew Critch argues that acausal trade mostly won’t route through simulations. Simulations are very expensive, and he expects there to be better alternatives for most of the acausal economy, such as much short proofs about what agents would agree to do. Critch believes the process of reflecting on those proofs is actually fairly similar to regular ol’ moral philosophy – reasoning about what simple concepts alien intelligences are likely to want or respect.

This isn’t a settled topic, but I personally find Critch’s take useful for thinking through “what would the overall acausal economy look like?”. And I suspect this is a good thinking-prompt for people who are currently worried about one particular edge case in the acausal economy, to give more perspective of how acausal society might fit together.

Here’s an excerpt: the Acausal Normalcy post:

Many sci-fi-like stories about acausal trade invoke simulation as a key mechanism.

The usual set-up — which I will refute — goes like this. Imagine that a sufficiently advanced human civilization (A) could simulate a hypothetical civilization of other beings (B), who might in turn be simulating humanity (B(A)) simulating them (A(B(A)) simulating humanity (B(A(B(A)))), and so on. Through these nested simulations, A and B can engage in discourse and reach some kind of agreement about what to do with their local causal environments. For instance, if A values what it considers “animal welfare” and B values what it considers “beautiful paperclips”, then A can make some beautiful paperclips in exchange for B making some animals living happy lives.

An important idea here is that A and B might have something of value to offer each other, despite the absence of a (physically) causal communication channel. While agreeing with that idea, there are three key points I want to make that this standard story is missing:

1. Simulations are not the most efficient way for A and B to reach their agreement. Rather, writing out arguments or formal proofs about each other is much more computationally efficient, because nested arguments naturally avoid stack overflows in a way that nested simulations do not. In short, each of A and B can write out an argument about each other that self-validates without an infinite recursion. There are several ways to do this, such as using Löb’s Theorem-like constructions (as in this 2019 JSL paper), or even more simply and efficiently using Payor’s Lemma (as in this 2023 LessWrong post).

2. One-on-one trades are not the most efficient way to engage with the acausal economy. Instead, it’s better to assess what the “acausal economy” overall would value, and produce that, so that many other counterparty civilizations will reward us simultaneously. Paperclips are intuitively a silly thing to value, and I will argue below that there are concepts about as simple as paperclips that are much more universally attended to as values.

3. Acausal society is more than the acausal economy. Even point (2) isn’t quite optimal, because we as a civilization get to take part in the decision of what the acausal economy as a whole values or tolerates. This can include agreements on norms to avoid externalities — which are just as simple to write down as trades — and there are some norms we might want to advocate for by refusing to engage in certain kinds of trade (embargoes). In other words, there is an acausal society of civilizations, each of which gets to cast some kind of vote or influence over what the whole acausal society chooses to value.

This brings us to the topic of the present post: acausal normalcy, or perhaps, acausal normativity. The two are cyclically related: what’s normal (common) creates a Schelling point for what’s normative (agreed upon as desirable), and conversely. Later, I’ll argue that acausal normativity yields a lot of norms that are fairly normal for humans in the sense of being commonly endorsed, which is why I titled this post “acausal normalcy”.

A new story to think about: moral philosophy

Instead of fixating on trade with a particular counterparty B — who might end up treating us quite badly like in stories of the so-called “basilisk” — we should begin the process of trying to write down an argument about what is broadly agreeably desirable in acausal society.

As far as I can tell, humanity has been very-approximately doing this for a long time already, and calling it moral philosophy. This isn’t to say that all moral philosophy is a good approach to acausal normativity, nor that many moral philosophers would accept acausal normativity as a framing on the questions they are trying to answer (although some might). I’m merely saying that among humanity’s collective endeavors thus far, moral philosophy — and to some extent, theology — is what most closely resembles the process of writing down an argument that self-validates on the topic of what {{beings reflecting on what beings are supposed to do}} are supposed to do.

This may sound a bit recursive and thereby circular or at the very least convoluted, but it needn’t be. In Payor’s Lemma — which I would encourage everyone to try to understand at some point — the condition ☐(☐x → x) → x unrolls in only 6 lines of logic to yield x. In exactly the same way, the following types of reasoning can all ground out without an infinite regress:

reflecting on {reflecting on whether x should be a norm, and if it checks out, supporting x} and if that checks out, supporting x as a norm

reflecting on {reflecting on whether to obey norm x, and if that checks out, obeying norm x} and if that checks out, obeying norm x

I claim the above two points are (again, very-approximately) what moral philosophers and applied ethicists are doing most of the time. Moreover, to the extent that these reflections have made their way into existing patterns of human behavior, many normal human values are probably instances of the above.

(There’s a question of whether acausal norms should be treated as “terminal” values or “instrumental” values, but I’d like to side-step that here. Evolution and discourse can both turn instrumental values into terminal values over time, and conversely. So for any particularly popular acausal norm, probably some beings uphold it for instrumental reasons while others uphold it has a terminal value.)

Again, this topic isn’t very well explored or settled. I’ve heard some arguments that superintelligences might use neither proofs nor simulations but instead use model-based reasoning, or use a mix of techniques.

But the overall point is that if there are meaningful interactions with any distant superintelligences, there are probably meaningful interactions with many. The situation is probably massively multipolar, a sort of gigantic acausal society or network. Probably we humans can’t participate in it at all yet, but even if we can, it’s probably not going to just be an isolated interaction between us and one other entity. It’ll be more like us being a child in a room full of adults, some friendly, others not. There’ll be norms, laws, reciprocal relationships, etc. that the adults have between each other.”

For some people, if you’re having trouble getting out of the acausal extortion anxiety loop and need your thoughts to go somewhere, it might be helpful to think about acausal trade through this frame, and think in terms of “okay, what would productive acausal societies actually do?”.

I’m somewhat optimistic that thinking through this topic would be helpful for a) giving the “acausal stuff” thoughts in your brain something to latch onto that feels connected to their existing thought loops, which is genuinely interesting, that doesn’t contribute to the anxiety spiral.

Okay… maybe… but, I dunno, I’m still anxious about this. What do I do?

Well, as noted earlier, I expect different things to work for different people.

I think in general, getting some exercise and sleep and eating well and hanging out with friends doing things is probably an important component. If your sleep/exercise/social-life isn’t hitting a baseline level of healthiness, I think it’s worth prioritizing that, and it’ll probably give you space/resources to think more clearly.

Getting enough sleep and exercise can be pretty challenging, to be fair. (If exercising at all is a struggle, I’d start with something like a 10 minute walk)

I think if you’re finding yourself preoccupied with this question in an intrusive, persistent way, I think you might check with a psychiatrist about whether you have symptoms of depression or anxiety that warrant medical intervention. I don’t know how often this’ll be the problem, but I’d offhand bet it’s relevant in >30% of cases where someone is anxious about this for more than a month. Maybe look into Scott Alexander’s Things That Might Help If You Have Depression.

I do expect talking to a therapist to be helpful. The process of getting a good therapist can be a bit of work (it typically involves shopping around a bit for someone who clicks with you), but if you’re really anxious about this it may be worthwhile.

If getting a therapist seems too hard, you can try using some CBT self-help books, or talking to some friends.

If you have the specific problem of “Well, I tried talking to friends but they were kinda dismissive of the problem, rather than taking it seriously, so I didn’t feel like they were really engaging with me”, here’s a script that might help:

“Hey, so, I’ve been pretty anxious about this philosophy thought experiment. I’ve read some stuff arguing that I shouldn’t have to worry about it, but I don’t feel fully resolved about it. Could you help me think about this for a couple hours? I’d like to get to a stage where I feel like I’ve wrapped my head around it enough to move on. I know you’re probably skeptical that this makes any sense at all, but, it’d be really helpful to me if you took it seriously enough to help me orient to it for one or two conversations.”

Some things that script is aiming to achieve:

Making a time-bound commitment. Sometimes friends are nervous (for good reason) about helping each other with psychological problems that seem to never get better. My guess is one conversation isn’t enough to really resolve things, but I think two conversations is a reasonable ask that many friends would be up for doing. Take some space in between conversations to process things so that the second conversation has a reasonable chance of helping wrap things up.

It’s trying to own the goal of “understand it enough to move on”, which helps reassure your friend that you are working towards closure.

I expect talking to a friend in person (or videochat) to be more helpful than talking through text online, because one of the things that’s important here is reassuring your monkey brain that things are fairly normal and okay. It’s harder to do that through text (but, again, your mileage may vary).

These are all my first guesses. I haven’t actually seen a person who went through the transition to “really worried” to “not worried”, so I’m not sure what tends to work for people in this situation.

I do know ~100 people who take acausal trade seriously, but who treat it in a pretty chill fashion, aren’t worried about acausal extortion, and mostly focus on their day-to-day living. Some of them are working explicitly on helping to ensure the AI alignment problem is solved. Some of them are working on concrete problems in the world. Some of them are just generally living life, having fun nerdy gatherings and hiking and making music or whatnot and holding down a day-job.

In general it is possible to live your life understanding that AI is coming and the future might be pretty strange, while still appreciating your day to day life, and not being too stressed about it.

- How can I get help becoming a better rationalist? by (13 Jul 2023 13:41 UTC; 31 points)

- 's comment on What constitutes an infohazard? by (8 Oct 2024 21:43 UTC; 12 points)

- Four levels of understanding decision theory by (1 Jun 2023 20:55 UTC; 12 points)

- 's comment on Tuning your Cognitive Strategies by (29 May 2023 19:28 UTC; 11 points)

- 's comment on AI Safety in China: Part 2 by (23 May 2023 17:24 UTC; 4 points)

I agree with Eliezer that acausal trade/extortion between humans and AIs probably doesn’t work, but I’m pretty worried about what happens after AI is developed, whether aligned or unaligned/misaligned, because then the “acausal trade/extortion between humans and AIs probably doesn’t work” argument would no longer apply.

I think fully understanding the issue requires solving some philosophical problems that we probably won’t solve in the near future (unless with help of superintelligence), so it contributes to me wanting to:

(Not sure if you should include this in your post. I guess I would only point people in this direction if I thought they would make a positive contribution to solving the problem.)

Yeah I’ve been a bit confused about whether to include in the post “I do think there are legitimate interesting ways to improve human frontier of understanding acausal trade”, but I think if you’re currently anxious/distressed in the way this post is anticipating, it’s unlikely to be a useful nearterm goal to be able to contribute to that.

i.e. something like, if you’ve recently broken up with someone and really want to text your ex at 2am… like, it’s not never a good idea to text your ex, but, probably the point where it’s actually a good idea is when you’ve stopped wanting it so badly.

Setting “moving on” as the goal is a form of not taking something seriously. It is often the thing to do. This follows from productive research not being something you can do, or not being a thing you should be doing instead of other things, if that happens to be the case. It’s very often the case, but not tautologously so.

If it is productive, it should feel productive, otherwise it shouldn’t.

I removed the “productive” clause from the sentence. It wasn’t really adding much to the sentence anyway.

I agree with your description of “moving on”, but am not sure what to do with the paragraph. The paragraph is targeted towards a) people who are irrationally/compulsively fixated on acausal extortion, and b) specifically, people whose friends are already kinda sick of hearing about it.

I think it’s an important question from the inside of how to tell whether or not you’re irrationally fixated on something vs rationally orienting to something scary. I think AI is in fact at least moderately likely to kill everyone this century, and, unlike acausal extortion, I think the correct response to that one is “process/integrate the information such that you understand it and have maybe grieved or whatever, and then do whatever seems right to do afterwards.”

At first glance, the arguments for both AI doom and acausal extortion are probably similarly bewildering for many people, and it’s not clear where the boundary of “okay, I’ve thought about this enough to be roughly oriented” is. I think ideally, the OP would engage more with that question, rather than me sort of exasperatedly saying “look, man, acausal extortion isn’t that big a deal, chill out”, but I wasn’t sure how to go about it. I am interested in suggestions.

My model of the target audience was very indignant at the “moving on” suggestion that doesn’t rest on an object level argument (especially in context of discussing hypothetical friends who are not taking the concern seriously). Which is neither here nor there, since there is no object level argument available for this open question/topic. At least there is a meta argument about what’s actually productive to do. But interventions on the level of feelings is not an argument at all, it’s a separate thing that would be motivated by that argument.

Curiosity/value demands what’s beyond currently available theory, so the cutoff is not about knowing enough, it’s pragmatics of coping with not being able to find out more with feasible effort.

I think a relevant argument is something like anti-prediction, there is a large space of important questions that are all objectively a big deal if there is something to be done about them, but nonetheless they are pragmatically unimportant, because we do not have an attack. Perhaps it’s unusually neglected, that’s some sort of distinction.

I updated the opening section of the post to be a bit less opinionated and more explain-rather-than-persuade-y. Probably should also update the end to match, but that’s what I had time to do in this sitting.

Strongly agree. Two points to add/potential traps to avoid:

“Not clicking” is usually easy to spot, but “clicking” might not be, and can be there but incomplete, and can change over time as what you need, and where you are in your mental health journey, changes.

You don’t need to make your therapist understand acausal trade in order to work on your anxiety about acausal trade. That kind of thinking and interest doesn’t need to be part of the clicking.

If you want more technical reasons for why you shouldn’t worry about this, I think Decision theory does not imply that we get to have nice things is relevant. In humans, understanding exotic decision theories also doesn’t imply bad things, because (among other reasons) understanding a decision theory, even on a very deep and / or nuts-and-bolts level, is different from actually implementing it.[1]

Planecrash is a work of fiction that may give you a deep sense for the difference between understanding and implementing a decision theory, but I wouldn’t exactly recommend it for anyone suffering from anxiety, or anyone who doesn’t want to spend a lot of time alleviating their anxiety.

Hi! I really appreciate the dedication to help people to calm down people, like myself, about acausal extortion. I have thought about this type of subject for 10 months-ish and i have gathered some opinions (feel free to debunk them): 1) i think these ideas are actually dangerous if thought in extensive detail, 2) even if you do get bitten by a blackmail, it doesen’t mean it will 100% happen, and 3) ignoring them seems to be a good idea. I have tried recently to confront my fears about them in these last couple of days reading different pages including this one, and i feel somewhat stuck. Ive also thought about acausal extortion between humans or aliens. My main anxiety is weather i have thought too much in detail about all of this, and i can’t quite find a way to let go in a satisfactory manner: basically i thought about an ai or alien or human, thinking about some of their characteristics in a kind of general way.

I also can’t quite tell what the concensus is on these ideas, if there even is one. Im not sure wether i understand the “acausal normalcy” page (feel free to correct my following points); the post basically talks about how instead of simulations it is better to argue wether this or that entity might do x or y, which honestly makes it a bit more scary now, even though the post was trying to help those anxious like myself, and the other point in the post was that there is a whole society of acausal interaction, and that probably the most common value that acausal entities have is boundries, and he says that you should have the attitude of: “if you want to interact with me you should respect me”.

( By the way, i am absolutely aware of how long this comment is). Also i do agree with you Raemon on the “their anxiety leeds them to fulfill the anxiety loop”, because that literally happened to me.

This has low enough karma to feel like a signal of “something here isn’t right”, enough such that I’m not sure if I’d link it to new users who seem in the target demo reference class.

I’m interested in whether downvoters were more thinking something like:

It seems generally sketchy to jump to the assumption that someone has an anxiety problem rather than engaging with it intellectually. (Maybe fair. FYI if you downvoted early for this reason, I’m curious if my reworked edit of the opening sections makes it any better)

Disagreements with the technical answers (maybe thinking it’s premature to list Acausal Normalcy as a reference since it hasn’t been super vetted at this point?)

This seems like an important caveat to TsviBT’s Please don’t throw your mind away, which offers similar advice but just says to think about whatever comes to mind and see where it goes; I can see this de-facto steering people’s thinking towards negative/unhelpful attractor states.

SquirrelInHell touches on this:

“Any potentially blackmailing AI would much prefer to have you believe that it is blackmailing you, without actually expending resources on following through with the blackmail, insofar as they think they can exert any control on you at all via an exotic decision theory. Just like in the one-shot Prisoner’s Dilemma, the “ideal” outcome is for the other player to believe you are modeling them and will cooperate if and only if they cooperate, and so they cooperate, but then actually you just defect anyway. For the other player to be confident this will not happen in the Prisoner’s Dilemma, for them to expect you not to sneakily defect anyway, they must have some very strong knowledge about you.” I don’t understand why this needs to be the case as opposed to a scenario where the AI reasons that torture slightly increases the probability that you will cooperate. Even if it requires the expenditure of resources, if doing so increases the probability of the AI coming into existence in the first place, it might still make sense for the AI in question.

I would appreciate if someone would explain where I’ve made a mistake.