Power Overwhelming: dissecting the $1.5T AI revenue shortfall

This post was originally posted my Substack. I can be reached on LinkedIn and X.

The US economy is all-in on AI, with data center capex responsible for 92% of US GDP growth in the first half of 2025. OpenAI alone is expected to spend $1.4T on infrastructure over the next few years, and caused a controversy on X when asked about its revenue-capex mismatch. So, can AI deliver the required ROI to justify the trillions in capex being put into the ground, or are we doomed to see a repeat of the Telecom bubble?

The industry is operating in a fog of war. On one hand, AI labs like OpenAI and hyperscalers all cite compute shortages as a limiter on growth, and Nvidia continues to crush earnings. But on the other, actual AI revenues in 2025 are an order of magnitude smaller than capex. This post attempts to dissect this fog of war and covers the following:

A state of the union on current AI capex

How the quality and trajectory of AI application revenues impact cloud vendors

Why there is a $1.5T AI revenue shortfall relative to capex

How AI clouds are different from traditional data centers and the fundamental risks in the AI data center business model

How internal workloads from the Magnificent Seven ultimately decide whether we avoid an “AI winter”

A framework for investors to navigate the current market turbulence, across both public and private markets

Let’s dive in.

The dominant narrative is the mismatch between AI capex and AI application revenues

To understand the current state of AI euphoria, it’s helpful to go all the way back to 2022, when the software industry was facing significant headwinds on the back of rising interest rates. The SaaS crash was short-lived, as the launch of ChatGPT in late 2022 rapidly reoriented investor interest around AI. The dominant narrative was that AI would replace headcount, not software budgets, unlocking trillions in net new revenues. There were also technical trends that drove demand for compute: the rise of reasoning models, AI agents, and post-training. As a result, we saw capex rapidly rise in the second half of 2024.

Fast forward to present day, AI revenues have indeed exploded. By the end of 2025, OpenAI expects to reach $20B in annualized revenues while Anthropic is expected to reach $9B. But cracks are beginning to appear: even the most dominant technology companies are seeing their balance sheets shrink due to their AI capex, requiring them to tap into the debt markets.

Are we in bubble territory? My mental model is to look at application layer AI spend, AI cloud economics, and hyperscalers’ own workloads to answer several quintessential questions.

What are revenue scale & growth rates of AI application companies?

Is there a compute overbuild and do AI capex depreciation schedules actually make sense?

For the Magnificent Seven / AI labs: do internal workloads make AI capex “math out”?

Growth rates and quality of revenues are key concerns in software-land

At the app layer, while apps like ChatGPT are delivering real value, a material portion of AI is in a period of experimentation. The unintended effect is that AI revenues get artificially inflated, introducing systemic risk to cloud vendors as they end up deploying capex against potentially phantom demand. We see signs of this across both the private and public markets.

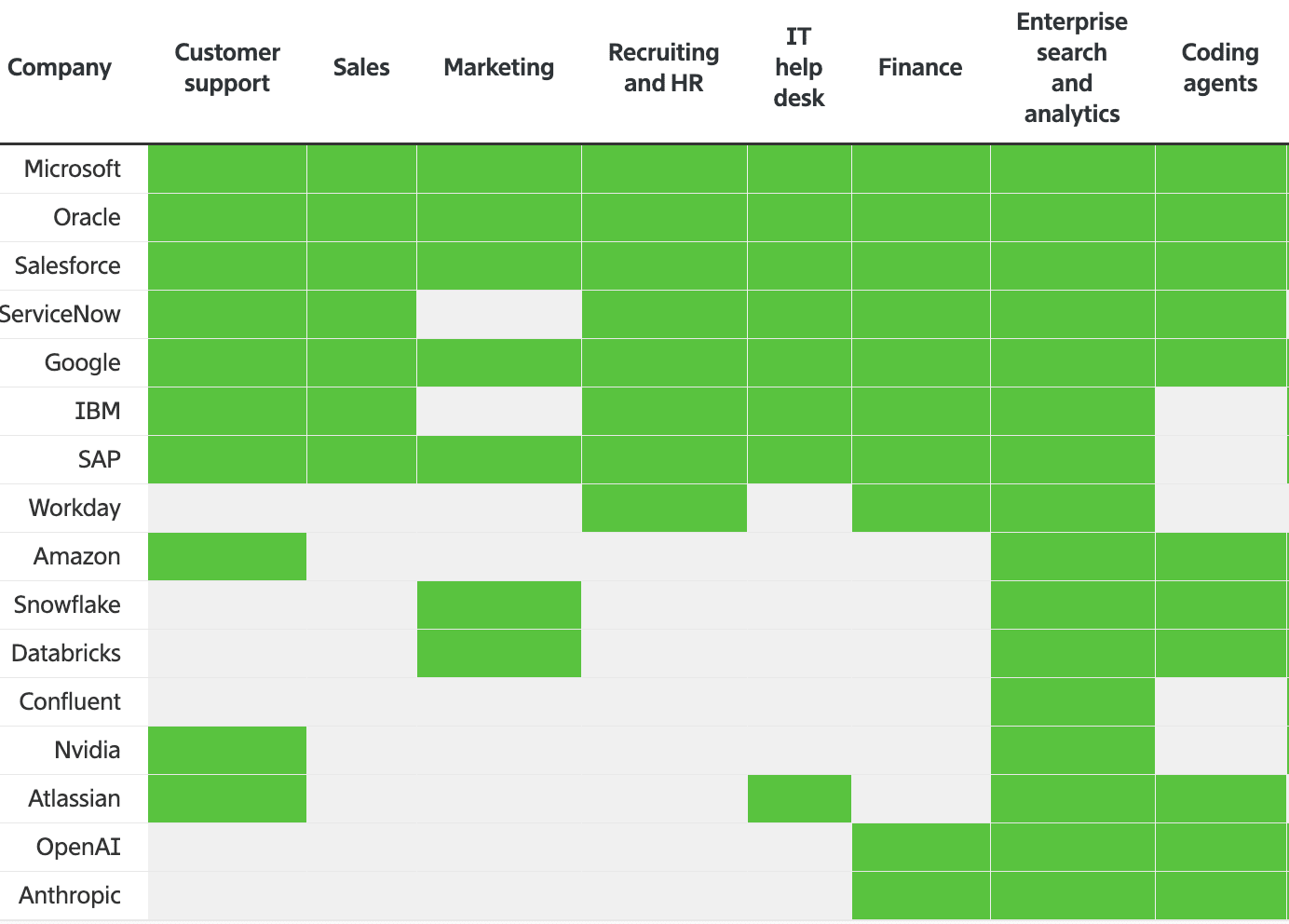

In startup-land, companies serving use cases beyond chatbots and coding are starting to reach scale (the Information estimates that aggregate AI startup revenues are ~$30B as of December 2025). But the quality of these revenues is unclear. Taking enterprise software as an example, AI spend can partially be explained by demand pull-forward as CIOs scramble to implement AI (e.g. AI agents for various use cases) and piloting products from multiple vendors. Already, there are concerns that these deployments are failing to deliver value. After this initial experimentation phase, customers will end up narrowing down their list of vendors anyway. My intuition here is that many enterprise use cases require several iterations of product development and heavy customization to deliver value, slowing the pace of AI diffusion.

Another major risk is the rapid decline in dry powder (capital available to be invested in startups), as startups that fail to raise new capital will also reduce their cloud spend. Given how much capital is deployed to AI startups, VC has an impact on potentially $50B+ of cloud spend. Early-stage startups will be the hardest hit as firms that have traditionally written checks into seed / series A startups are already having trouble fundraising. I expect that the bulk of the remaining dry powder will concentrate to the handful of AI labs that have reached escape velocity as well as “neolabs” (SSI, Thinking Machines, Richard Socher’s lab, etc.).

Moving on to the public markets, we see a re-acceleration and subsequent re-rating of AI “picks-and-shovels” names that provide building blocks like databases, networking, observability (companies in black). These companies sell to established companies and hypergrowth startups (e.g. Datadog selling to OpenAI) and have benefited from the current AI tailwinds. They will be impacted if AI application revenue growth stalls or declines.

In terms of SaaS pure-plays (companies in red), there are two ways we can look at things: the current narrative around SaaS and the actual AI revenues these companies are generating. From a narrative perspective, the consensus is that SaaS companies derive some proportion of their value from complex UIs and risk being relegated to “dumb databases” if AI performs tasks end-to-end. Customers are also experimenting with building software that they’ve traditionally paid for (e.g. building a CRM vs. paying for Salesforce). While some apps can be replaced, many companies are not accounting for the “fully-loaded” costs of running production software in-house (e.g. continuous upgrades, incident response, security).

As a result, even companies with strong growth rates, like Figma, have seen their stock price collapse. The revenue multiples for the vast majority of public software startups have now retreated to their historical medians (see below). One of the few counterexamples is Palantir, which is trading at higher multiples than OpenAI! My view is that investors are conflating two things: the threat of AI, and the natural saturation of SaaS (the plateauing of growth as certain categories of SaaS reach peak market penetration).

The second observation is that SaaS pure-plays are seeing a moderate growth re-acceleration due to AI:

ServiceNow, now at a $13.6B run-rate, expects its $500M in AI revenues to double in 2026

Salesforce’s Agentforce now generates $440M ARR as of its most recent reporting quarter

What this tells us is that AI revenues are growing, but only currently make up a small portion of these companies’ overall revenues. Across public companies and startups, back-of-the-envelope estimates suggest that aggregate AI revenues are in the mid-tens of billions of dollars.

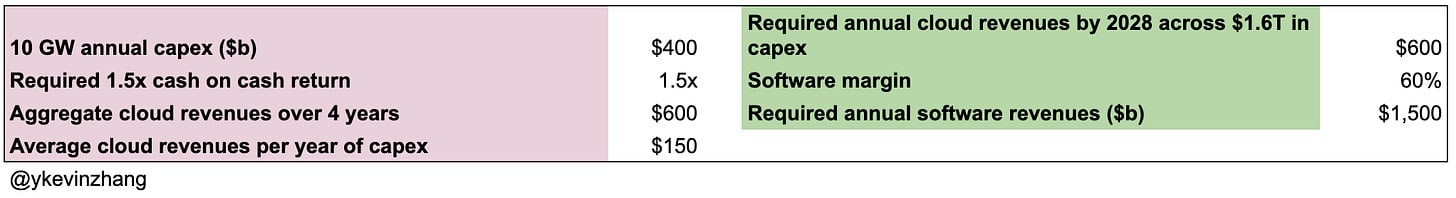

The $1.5T AI revenue hole

This leads us to the next question: what do AI revenues have to grow to in order to justify the trillions in capex that are coming online in the next few years (2027/2028)? We can get a sense of this mismatch from the chart below, which is a highly conservative model of the required lifetime revenues just to pay back cloud capex.

If we make things a bit more realistic:

Capex from non-AI workloads is excluded to illustrate the required incremental AI revenues. One way to do this is to take capex from 2020-2022, which is ~$100B per year, and subtract it from total capex. For example, ~$300B of capex in 2025 would go towards AI, while the remaining ~$100B go toward traditional workloads

$400B (10GW) in annual AI-only cloud capex from 2024 through 2027 ($1.6T in total). This overestimates AI capex in 2024/2025, and significantly underestimates AI capex in 2026/2027

Hyperscalers expect a ~1.5x cash-on-cash return, and cloud revenues are generated equally across the lifetime of the datacenter

4-year hardware life cycle (this makes the revenue math a bit cleaner)

60% software margins (down from typical SaaS gross margins of 80%+)

By 2028, AI inference dominates AI workloads for application-layer companies

Based on the calculations above, we’d need to fill a $1.5T revenue hole by 2028! To put things in perspective, the global SaaS market in 2024 was only ~$400B. The bet at this point is that broad swathes of white collar work will be automated. Even if OpenAI and Anthropic hit their projections in 2028 ($100B for OpenAI, $70B for Anthropic) and AI software collectively generates an additional ~$300B in revenues, we’re still $1T short! Said another way, if AI revenues are ~$50B now, we’d need to grow AI revenues by ~30x by 2028!

Furthermore, only a subset of these revenues actually “flow through” to cloud vendors (in blue).

This is how to understand the flow of revenues:

App-layer companies need a way to deploy their AI features, and can use models from AI labs or train their own models / use open-source ones (Airbnb uses Alibaba’s Qwen). They deploy their models on hyperscalers & neoclouds

AI labs train their models and generate the bulk of their revenues from applications like ChatGPT or via API access. Labs currently rely on hyperscalers & neoclouds but have ambitions of becoming cloud vendors themselves

Hyperscalers & neoclouds sell a broad range of AI services, from bare metal compute to managed API endpoints

Google has offerings at every layer of the stack, with a viable ChatGPT competitor, its own leading model, a $60B run-rate cloud business, and its in-house silicon

If application companies use AI labs’ APIs, their spend won’t directly flow into cloud vendors, as AI labs would be paying cloud hyperscalers as part of their COGS. If there’s a mass migration to open-source models, then AI labs won’t hit their revenue projections. Both scenarios require AI revenues to be greater than $1.5T to account for some of this “double counting”.

We’re not in Kansas anymore: the uncertain economics for AI cloud capex

Now, even if AI revenues catch up, is the AI cloud business model even a good one? Here, the core concern is that AI hardware obsolescence happens faster than for traditional data center hardware. To understand the risks that AI clouds face, it’s helpful to understand what made traditional clouds profitable:

Longer depreciation cycles because Moore’s Law (chip performance doubles every 18 months) had already slowed down, so older generation hardware could maintain pricing power vs. GPU-only hardware

The ability to layer on much higher margin software (database software, observability, etc.)

Predominantly CPU-bound workloads which is great for multi-tenancy, either via virtual machines or containers, though GPU multi-tenancy is now a thing

We can see how profitable a pre-ChatGPT era data center was using a hypothetical $5B data center build, with the following assumptions:

5-year depreciation schedule for IT hardware

5% revenue “step down” from one year to the next to account for older hardware being cheaper to rent

The $5B capex only includes equipment, and not the actual shell (the buildings that house IT equipment, as that lasts significantly longer)

Capex comes online in two phases to account for longer data center build times

Proceeds from depreciated hardware are included for simplicity

Our hypothetical model shows that we get a reasonably attractive ~15% unlevered IRR and ~1.5x cash-on-cash returns. Hyperscalers can juice these returns with leverage given their access to cheap debt. Another thing to note here is that cashflows “pay back” capex as well as other ancillary costs (e.g. R&D, etc.) in ~3 years, and FCF from the “out years” are pure profit.

AI data centers are very different. First, the speed at which Nvidia releases new architectures means that hardware performance has been increasing significantly relative to that of CPUs. Since 2020, Nvidia has released a major new architecture every ~2 years.

As a result, older GPUs rapidly drop in price (see below). The per-hour GPU rental price of the A100, released in 2020, is a fraction of the recently released Blackwell (B200). So, while the contribution margin of the A100 is high, the rapid decline in price / hour means that IRR ends up looking unattractive. Furthermore, a material portion of the inference compute online now is from the 2020-2023 era, when capex was in the ~$50-100B scale. Now that we’re doing $400-600B a year in capex, there is real risk that Mr. Market is overbuilding.

The other risk is the unrealistic depreciation schedules of AI hardware. Most cloud vendors now depreciate their equipment over 6 years instead of 4 or 5. This made sense in the old regime when there wasn’t a real need to replace CPUs or networking equipment every 4 years. In the AI era, 6 years means 3 major generations of Nvidia GPUs! If Nvidia maintains its current pace of improvements and more supply comes online, then serving compute from older GPUs might well become uneconomical, which is why clouds push for long-duration contracts.

Now, if there’s truly significant demand (Google has stated that it needs to double compute 2x every 6 months), then older GPUs will likely be fully utilized and generate good economics. If the counterfactual is true, then clouds without strong balance sheets risk being wiped out.

The Magnificent Seven Cavalry to the rescue?

So far, we’ve established that app-layer AI spend is unlikely to generate enough inference demand, and that AI clouds may be a poor business model. This means that the only remaining buyers of compute are the Magnificent Seven (Alphabet, Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Amazon in particular) and AI labs (specifically their training workloads, as we’ve already accounted for their inference workloads). We can segment their workloads into three buckets:

Net new products, like Google’s AI Overviews replacing traditional search results

“Lift-and-shift” workloads, for example using beefier models for more precise ad targeting or better recommender systems for YouTube Shorts & Instagram Reels

R&D and training runs for new models

In terms of net new product experiences, Google serves as a good example. In October, the search giant announced that it reached 1.3 quadrillion tokens processed monthly across its surfaces (which is purposefully vague marketing). We can estimate what revenue this translates to if Google “bought” this inference on the open market via the following assumptions:

Use publicly facing API pricing for Gemini 3 Pro / Gemini 2.5 Flash (its high-end and low-end models, respectively) and assume that Google generates 80% API margins

Workloads have an 80⁄20 split between low-end and high-end models, and that the ratio between input tokens and output tokens is 4:1

20% volume discount

This results in $17B in cloud revenues from serving AI across Google’s entire product surface, and is likely an overestimation because a portion of these “tokens processed” comes from things like the Gemini API / chatbot (so it’s already accounted for on Alphabet’s income statement).

Moving on to lift-and-shift workloads, Meta’s revenue re-acceleration in Q3 (26% YoY) serves as a case study of how AI was used to generate better recommendations and serve more precise ads. This resulted in a few billion dollars in incremental revenues. We’re likely still in the early innings of these lift-and-shift workloads (e.g. LLMs in advertising), so I expect revenues to continue growing until low-hanging fruits get picked.

Finally, we have R&D compute costs. By 2028, OpenAI’s R&D compute spend is expected to be around ~$40B. Assuming major players (e.g. Alphabet, Meta, OpenAI, Anthropic, etc.) spend similar amounts on R&D, a fair upper limit on total R&D compute is ~$200-300B.

Now, it’s difficult to predict how much will be spent on these three “buckets”, but from a game theory perspective, companies will spend whatever it takes to defend their empires and grow market share. More importantly, the dollars spent on internal workloads reduce the required AI app revenues. Assuming app-layer companies get 60% margins and internal workloads are delivered “at cost”, each dollar of internal workload equals $2.5 of AI app revenues. For example, if internal workloads in total only amount to $200B, then AI app revenues need to hit $1T. However, if internal workloads hit $500B, then app revenues only need to reach $250B! This means that the AI bubble question depends on the spending habits of ~5 companies!

A framework for navigating the AI cycle

My read from this exercise is that there’s likely a moderate overbuild, but not to the extent that alarmists are suggesting. And despite this fog of war, there are actionable insights for investors.

Public markets:

AI will fundamentally change the nature of work, but the broad replacement of human workers will take longer than AI accelerationists expect. Therefore, higher-growth software companies that control key workflows and data integrations will see a re-rating in categories where overhyped AI pilots fail to deliver adequate ROI. This is especially true for software companies that can thoughtfully layer on AI features on top of their existing product surfaces.

Select picks-and-shovel names that can potentially benefit from various technological tailwinds will see outlier returns (e.g. the continued growth of the internet, the explosion of AI inference, agentic commerce, etc.). This is an active area of interest for me.

Neoclouds have seen a run-up this year even accounting for the recent turbulence. The bet they are making is that they can parlay Nvidia’s GPU allocation into becoming hyperscalers themselves. It is unclear whether these companies’ business models make sense, and they might collapse under the weight of their debt

Mag Seven names with significant compute footprints have enough cash flows from their existing businesses to protect them from potentially poor AI cloud economics. The meta game is figuring out which company will receive the mandate of heaven next. Nvidia was king until Google’s Gemini models came out and the world realized TPUs were a thing. Meta is next if it can deliver another strong quarter and its upcoming Llama models are competitive

Startups:

AI startups are where the “action” is happening. Right now, VCs are assigning valuations that assume exit value in the $10B+ scale. This is exceptionally dangerous as current valuations are having material impact on portfolio construction

Therefore, ripping a few hundred million dollars into an established AI lab is higher EV than putting the same quantum of capital in an early-stage startup that will probably get acquihired at 1x liquidation preference

Ultimately, near-term sentiment will hinge on whether OpenAI and Anthropic can sustain their revenue trajectories, as their offerings remain the clearest barometers of AI adoption. But over a longer horizon, the internal workloads of the Magnificent Seven and leading labs, not app-layer revenues, will determine whether today’s capex supercycle proves rational. In this environment, maintaining liquidity is of paramount importance. And if an AI winter does arrive, the dislocation will set the stage for generating exceptional returns.

Huge thanks to Will Lee, John Wu, Homan Yuen, Yash Tulsani, Maged Ahmed, Wai Wu, David Qian, and Andrew Tan for feedback on this article. If you want to chat about all things investing, I’m around on LinkedIn and Twitter!

The projected revenues are provisional, but so is a lot of the capex. About 70% of a datacenter is compute equipment, which is the last thing to be installed. But permitting, power, and to some extent buildings and infrastructure need to be started much further in advance, already planning for the eventual scale, so the eventual scale would be gestured at much earlier than its capex needs to materialize. Only about a year before completion does most of the capex need to be real, while concrete projections might appear several years in advance.

If the project fails to go forward a year before completion, only 5-20% of capex would be spent, and given the uncertainty many such projects would attempt to do everything that’s still predictably buildable on schedule at the last possible moment. If the project fails (or ends up downscaled), the infrastructure that’s already prepared by that point could still wait a few years for the project to resume in some form, without losing a lot of its value. This is analogous to how currently some AI datacenters are being built at sites initially prepared for cryptomining.

Positing 50% margins might be important for AI company valuations, but a “struggling” AI company that undershot its $80bn revenue target and is only making $50bn would still be able to fulfill its $40bn per year obligations on the 4 GW of compute it ordered two years prior, for which $135bn in capex was spent starting a year prior on compute equipment by its cloud partner, which looked at the AI company’s finances and saw that it’s likely going to clear the $40bn bar it cares about. About $40bn was spent starting 1.5 years prior on buildings and infrastructure by its datacenter real estate partner, which similarly looked into the AI company’s finances then. Perhaps only $25bn out of the total $200bn of the overall capex for the 4 GW of compute was spent on preliminary steps based mostly on the AI company’s decision 2 years ago. Even that is not obviously wasted if the project fails to materialize on schedule.

And 2 years ago, what was announced was not the 4 GW project spanning 2 years, but instead a 15 GW $750bn project spanning 5 years, further muddying the waters. The real estate and infrastructure partners felt they could use the time to prepare, the cloud partners felt they could safely downscale the project in 3 years if it looked like it’s not going to work out in full, and the AI company felt the buzz from the press release economy could improve the outcome of its next funding round.

Very good point here—being able to back out does make the capex look less scary.

Business models will change significantly. I speculated here about one likely change. Robotics-related business models will probably become important by 2030.