Once we cure aging, what happens to prisoners serving life sentences?

Biogerontologist Aubrey de Grey claimed that the first person who will live to 1,000 years old has already been born. He believes this unprecedented expansion in lifespan will occur with Longevity Escape Velocity (LEV).

LEV is defined by technologist Ray Kurzweil in his book The Singularity is Nearer as:

A tipping point at which we can add more than a year to our remaining life expectancy for each calendar year that passes.

This means that our life expectancy could increase faster than we age, which under different scenarios would look something like this:

Once we achieve LEV, we’ll have effectively cheated death. How is this possible?

Kurzweil, an unabashed techno-optimist, predicts that during the 2020s, AI will combine with biotechnology to defeat humanity’s current degenerative chronic diseases like cancer, atherosclerosis, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s.

We are now using AI to find new drugs, and by the end of this decade we will be able to start the process of augmenting and ultimately replacing slow, underpowered human trials with digital simulations.

And it’s not just drugs, AI can also decrease the risk of surgery, as well.

The average human surgeon may perform several hundred surgeries per year, amounting to, at most, a few tens of thousands over a full career. By contrast, the AI powering robotic surgeons will be able to learn from the experience of any surgery that system performs, anywhere in the world. In addition, the AI will be able to perform billions of simulated surgeries, tinkering with unusual variables that would be impossible or unethical to train on in a clinical setting.

Ultimately, it may become far safer for AI to perform surgery compared to human hands (similar to how autonomous driving, trained on billions of simulated miles, has already proven to be safer than human drivers—once humanity deploys autonomous driving, we could save the 40,000 people that die annually in traffic accidents in the US, and the 1.2 million people that die every year worldwide).

As AI transforms more and more areas of medicine…we will then be able to start directly addressing the biological factors that now limit lifespan to about 120 years, including mitochondrial genetic mutations, reduced telomere length, and the uncontrolled cell division that causes cancer.

Even more optimistically, Kurzweil foresees (through the trajectory of Moore’s Law) that engineering will develop increasingly smaller computers such that in the 2030s we’ll develop:

Medical nanorobots with the ability to intelligently conduct cellular-level maintenance and repair throughout our bodies.

Take cars as an analogy. My great great grandfather purchased an original 1930 Ford Model A car and it’s been in my family for almost 100 years. It still runs because we’ve carefully maintained it and replaced any dysfunctional parts.

As with cars, the human body is also a machine—a biological one. So with the power of cellular-level nanobots, Kurzweil believes:

We will gain a similar level of control over our biology as we presently have over automobile maintenance. That is, unless your car gets destroyed outright in a major wreck, you can continue to repair or replace its parts indefinitely.

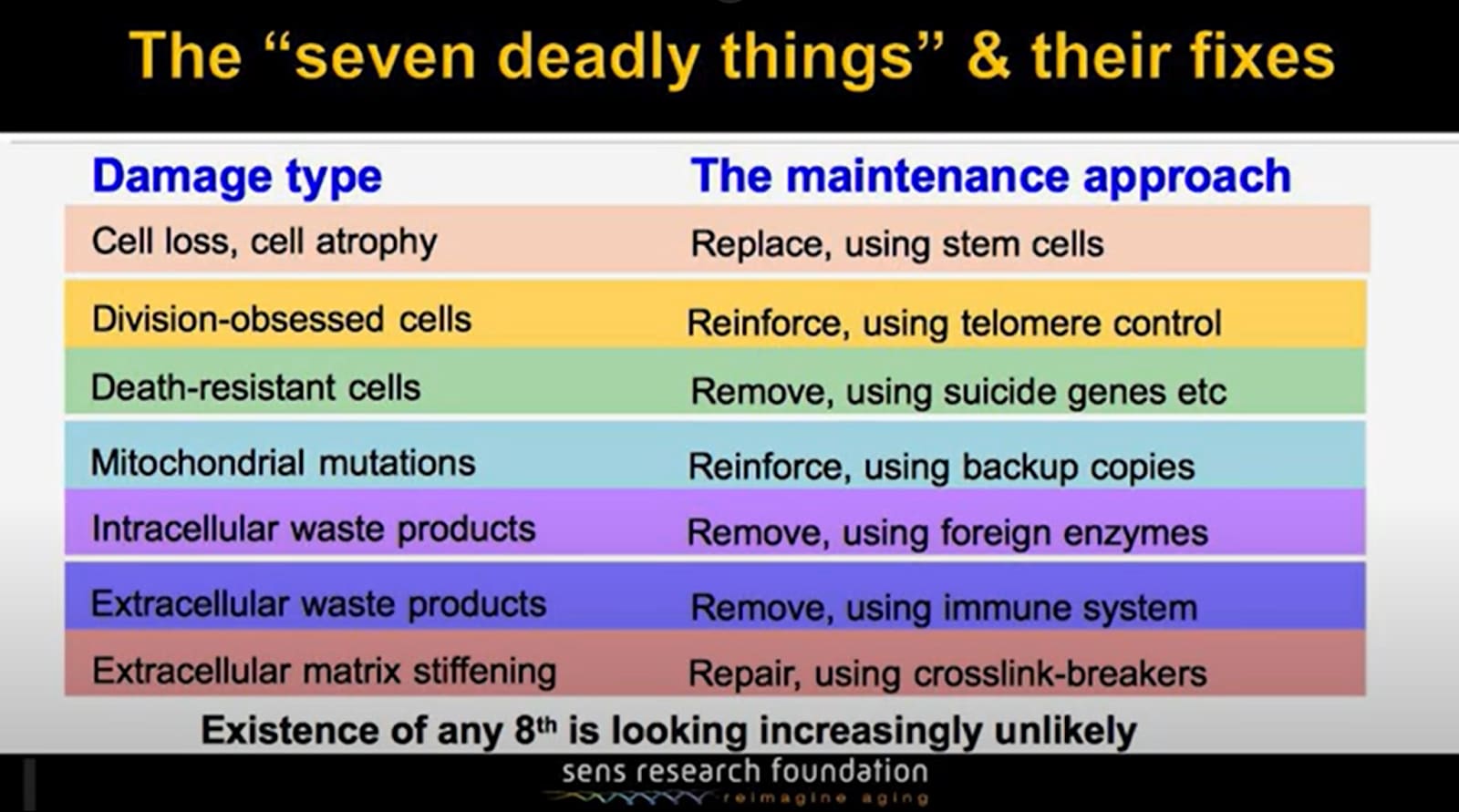

Similar to a mechanic’s checklist for car maintenance (e.g., check the engine pressure, oil level, blinker fluid), Aubrey de Grey in his TED Talk about defeating aging identifies seven core pathways through which the body ages and a checklist of potential solutions to mitigate them:

Through careful maintenance of our bodies, we could go on living to 200 years old, 300 years old, or even 1,000.

My question is:

When we defeat aging and just go on living, what will happen to all our prisoners serving life sentences?

Australian Charles Foussard served the longest recorded sentence, spending 70 years and 303 days in confinement from 1903 until 1974. He was institutionalized in a mental asylum after murdering an elderly man and stealing his boots. Foussard died at the age of 92 while still incarcerated.

This means that Foussard rotted away in an asylum during the invention of the Ford Model T car, World War 1, the discovery of penicillin, the widespread adoption of the radio, The Great Depression, World War 2, the adoption of television, Elvis Presley, the Civil Rights Movement, The Beatles, the first successful heart transplant, the Vietnam War, and putting the first man on the moon.

I don’t think Foussard, deemed criminally insane, ought to have been released. But I do want to challenge the humanity of his sentence and consider it with respect to the upcoming longevity explosion.

When looking at a list of prisoners given long sentences but not technically life imprisonment, it’s conceivable that US prisoner Gregory Aaron Gadlin (incarcerated for 16 counts of robbery and being a felon in possession of a weapon) who began his 967 year prison sentence in 2013 could actually serve his full term.

Obviously the judge who sentenced him expected him to die in prison. Yet legally, he will be set free in the year 2980. Perhaps the law will have to be reinterpreted to argue for the judge’s intent: that the government wants him to die behind bars. But if he duly serves the time he owes, we can’t arbitrarily change the law to prevent his release, right? Nevertheless, after stewing in prison for almost a millennium, do we think it’s a good idea for him to rejoin society?

Alternatively, we could deny prisoners with long sentences access to longevity healthcare and effectively murder them by condemning them to an early death of ~70 when the rest of us are living well past 700. And remember, prisoners are human, too. They are somebody’s son or daughter, somebody’s father or mother.

This begs the question: what’s the point of prison?

Do we want to punish people forever for their misdeeds (forcing them to potentially spend hundreds of years in a cell with the key thrown away), or will we acknowledge the kernel of humanity in criminals and try to rehabilitate them with the eventual goal of societal reintegration?

After all, it’s not Foussard’s fault that he’s criminally insane, right? He didn’t choose to be that way. Who would? He was born that way, or perhaps was molded into the shape of a monster due to a neglected or tortured childhood. Of course, he shouldn’t have simply been given a slap on the wrist and set free, but I think the punishment ought to fit the crime. And eternity in prison seems extreme.

We are coming closer to understanding the neurology of criminals. We know that, for example, shrunken prefrontal cortices and smaller amygdalae promote violence. Soon, we may be able to target and address antisocial behaviour on a neurological level.

If this sounds far-fetched, it’s good to remember that we’ve been here before.

In his book Determined: A Science of Life Without Free Will, author Robert Sapolsky writes that people used to blame epileptics for their condition (because of sins they committed, like masturbation). But scientific advances in neuroscience have shown that epilepsy is caused by overexcited neurons having nowhere to deposit neurotransmitters (and, apparently, not caused by masturbation). So scientists invented a type of medication that helps to treat epilepsy by regulating dopamine sensitivity.

We now view people with epilepsy not as malicious aberrants possessed by the devil, but instead as people with a medical condition.

Another example Sapolsky gives is for learning disabilities:

Kids who are having trouble learning to read and keep reversing letters aren’t lazy and unmotivated; instead, there are cortical malfunctions in their brains that cause dyslexia.

This is [yet] another domain where we have managed to subtract out the notion of blame from the disease (and, in the process, become vastly more effective at treating the disease).

Similarly, we now know that certain genes correlate with aggression. According to a meta-analysis on data from 24 genetically informative studies, “up to 50% of the total variance in aggressive behavior is explained by genetic influences.”

Perhaps we’ll eventually come to view antisocial, violent behaviour as a medical condition—like epilepsy or dyslexia—that needs treatment on the neurological level. So whether it’s for medical or criminal maladies, Sapolsky recommends the following quarantine approach for punishment:

| Quarantine Approach for Punishment | |

| Medical version | Criminology version |

|

|

One day—perhaps just a few decades from now—we’ll be able to give the one in seven people serving life sentences in the US (roughly 200,000 people) a choice:

“Hello, John Doe. As you know, you’re currently serving a life sentence in prison. Your neurological makeup, as it is now, is unsuitable for societal reintegration. Our data suggest that you’re suffering from a kind of…mental sickness…that’s incompatible with getting along with others and predisposes you to impulsive, sometimes violent behavior.

I do, however, have good news.

Similar to how we give people suffering from epilepsy anticonvulsant drugs that regulate their neurotransmitter levels, we’ve found a drug that helps to regulate your violent impulses. We’re willing to provide you this medicine, and once we’re confident that you’re stable and no longer a threat to the greater public, then you may leave prison and return to your family. Or, should you wish to refuse treatment, you’re free to remain locked up, possibly for hundreds or even thousands of years. The choice is yours.”

I don’t think the headline represents a practical or addressable question.

No government or legal system has ever maintained enough continuity to keep doing anything, including keeping any particular person in prison, for 967 years. And even if you technically have continuity in the institutions, before 2980, values and politics will probably have changed many times. The laws will change in all kinds of ways for reasons unrelated to any particular case, and so will the general conditions.

Depending on which ways things swing and in what order, I expect that, long before 2980, this guy will have--

been released;

been “cured” and released;

been executed;

been released, been retroactively de-released, and been released again;

gotten paperclipped along with everybody else;

transcended into a posthuman form and evolved to have completely different personality and motivations;

escaped, changed his name, moved to Fiji, gotten arrested for sodomy, and been sentenced to 3742 years for that; or

something else that will make the question moot.

The posts asks the addressable question of: what should we do about prisoner healthcare?

Ignoring the 967 years scenario (as that’s more of a hypothetical to conjure more abstract or philosophical thoughts in the reader), there’s still the issue of should longevity medicine be given to prisoners or not?

If yes:

Then the government is extending a prisoner’s incarceration (and suffering) for even longer if the prisoner is not set for release within hundreds of years, which seems cruel.

If no:

Then the government is condemning them to a premature death when the rest of us are living longer.

^Both of these options are suboptimal. The best case scenario is that we ignore them and find a third alternative: a rehabilitation-based approach to prison (versus the current confinement-based punishment).

I was with you right up to the part where I heard you implying that any large group of people can be effectively compelled to take any medication consistently over a long period of time. If you have some great way to get everyone to take all the drugs they’re supposed to, then pretty please apply it right now to causing people to take their full courses of prescribed antibiotics instead of just stopping once they “feel better”, and that’ll help slow down our accidental development of resistant bacteria.

Epileptics are a convenient example, because it’s so hard to imagine anyone insisting that they wouldn’t be themself without their seizures, and we don’t hear much about people deciding that the side effects of the medication for it are worse than the disease.

I suspect that the reality of (ongoing) medical treatments for criminal behavior is likely to more closely parallel the challenges that schizophrenics encounter with medication. In that case, the perceived subjective harms of taking the meds are much more closely balanced to the perceived subjective benefits. Most actual everyday average people, the kind of people with the deficits of luck or judgement that often correspond to incarceration, act as if they deeply believe that they should stop taking a medicine once they feel better from the condition it was prescribed to treat.

And even if people can be “fixed” in a one-off treatment, I’m getting popcorn for the lawsuits about religious discrimination when the system eventually encounters a prisoner of a faith with anti-medical views.

I know for Parkinson’s, there are focused ultrasound therapies being tested on patients. These are one time applications that are having lasting positive effects.

If we can apply something similar to antisocial behavior (if it can also be targeted in a specific brain region), then the taking-medicine problem can be avoided.

Apart from reforming criminals and protecting society, the justice system must satisfy victims’ desire for revenge. Otherwise, they or their loved ones will be too willing to execute it by themselves.

And with increased life longevity, it doesn’t feel just to punish someone with only a decade prison sentence for taking away near eternity of other person’s lifetime.

This sounds like you don’t understand how the law actually works. In the real world prisoners are frequently released without serving all the years that they are sentenced to serve. You don’t need to reinterpret the law to release someone earlier, you just need to apply the law as the law is actually applied in practice.

Parole is a thing.

I believe during sentencing a parole eligibility date is set. That date can, interestingly enough, be set way in the future—past the expected lifespan of the criminal.

The list I cited in my post (which is from Wikipedia) includes a section titled “Prisoners sentenced to one life imprisonment with possibility of parole after a period that exceeds a natural human life”.

Admittedly, I’m not the most knowledgeable when it comes to the law, do I have something wrong here?

A better question: can a person who is expecting to be executed sign up to cryonics?

As long as they’re OK with the cryonics provider getting them post-autopsy a week after death.

I really doubt they’re going to get timely access, and the chance that the instructions on that dogtag will be followed is probably about zero.

Can a person who is sentenced to a fine that would wipe out their savings planned for cryonics ask the judge nicely to be executed and frozen instead?

I’ve never seen anything against that in public cryonics signup paperwork, but that would be a great question to ask one of the labs offering it!

The legal system would probably start caring a lot more about prohibiting it once we figure out how to get people back after cryonics.