TL;DR

Dimensionalization is the practice of identifying and using quasi-independent axes or “dials” along which things vary. It’s the mental move behind tradeoff analysis, optimization, and design thinking. You are doing it already!

Unlike categorization or decomposition, dimensionalization preserves complexity but renders it navigable. Mastering it helps you think more clearly, decide more effectively, and communicate with greater precision.

A good decision isn’t just “good.” It’s good along the right dimensions, and good enough on the others to be worth it. You already know this; you just may not have named it. That naming, structuring mental move is dimensionalization. It is what enables us to see nuance.

You probably already dimensionalize:

Watching: familiar vs new, funny vs serious, short vs long.

Weekend: social vs solo, restful vs productive.

Shopping: quality vs price, speed vs reliability.

You don’t need to learn dimensionalization. But getting better at it makes you more precise, faster, and harder to bullshit.

So how does dimensionalization work?

Meta-Dimension 1: Fidelity

Dimensionalization is a perceptual act. It’s how you make fuzzy, complex phenomena legible. You take something like “vibe” or “quality” or “pain” and ask: what are the independent axes along which this varies?

Fidelity is how well your sliders map to reality. High-Fidelity dimensions reveal meaningful differences. They don’t collapse when you zoom out or vanish when you compare two related objects.

What makes dimensions high-Fidelity?

Validity: They track actual meaningful differences.

Stability: They hold up over time, context, or zoom level.

Examples:

High-Fidelity examples:

Quant investing: factor exposure, drawdown, alpha decay.

Software engineering: latency, modularity, throughput.

Listening to music: tempo, rhythmic complexity, texture, spatiality.

Homeowning: layout, light quality, maintenance, appreciation potential.

Making art: balance, composition, color harmony, movement.

Low-Fidelity examples:

Buzzwords without clarification (“Tech Debt”, “Efficiency”).

Aesthetic terms with no shared reference point (“Vibe”, “Quality”).

When Fidelity is low, you can still win, but you’re flying blind.

Meta-Dimension 2: Leverage

Leverage is how much change you get per dial twist. A good dimension is one you can actually move—and that, when moved, actually matters.

Dimensionalization unlocks Leverage. When you know the dimensions of a situation, you can manipulate inputs and predict outputs. You move from “is this good?” to “how does this score along the axes I care about?” Tradeoffs stop being vague feelings and become something you can reason about.

What makes a dimension high-Leverage?

Action: You can turn the dial.

Impact: The dial does something when you turn it.

High-Leverage examples:

Parenting: autonomy vs stimulation, structure vs flexibility.

Climbing: difficulty, exposure, endurance.

Career: compensation, autonomy, growth potential, mission.

Software engineering: modularity, performance, maintainability.

Low-Leverage examples:

Platitudes you can’t directly control (e.g. “more strategic” or “better parent”).

Metrics you don’t need (e.g. “innovativeness” or “meeting satisfaction score”).

Dials that don’t matter (e.g. “gym playlist bpm”).

High-Leverage dimensions are the ones that make tradeoffs visible and worthwhile. When you can dimensionalize, you can identify levers and see what happens when you pull them.

Meta-Dimension 3: Complexity

Dimensionalization only works if you can actually use it. Too many dials and you’ll burn out. Dimensionalization is powerful because it’s selective. It lets you summarize experience in low-dimensional space that your brain can handle.

Complexity is the price you pay to keep your dimensional model in RAM. If you can’t hold the dials in your head, you’ll fall back on gut or default heuristics.

What contributes to Complexity?

Cognitive Load: More sliders = more juggling.

Overfitting: Some dimensions give you theoretical resolution but no practical benefit.

Low-Complexity (good) examples:

Exercise: strength, endurance, recovery.

Personal finance: savings rate, risk tolerance, liquidity.

Parenting: hunger, tiredness, stimulation, attention.

High-Complexity (bad) examples:

Modeling your fitness plan on 30 biometric streams.

Tracking 50+ OKRs in a five-person company.

Running a life dashboard that requires updating a database.

Good dimensionalizations are efficient, not exhaustive. They give you a small set of sliders that explain a lot.

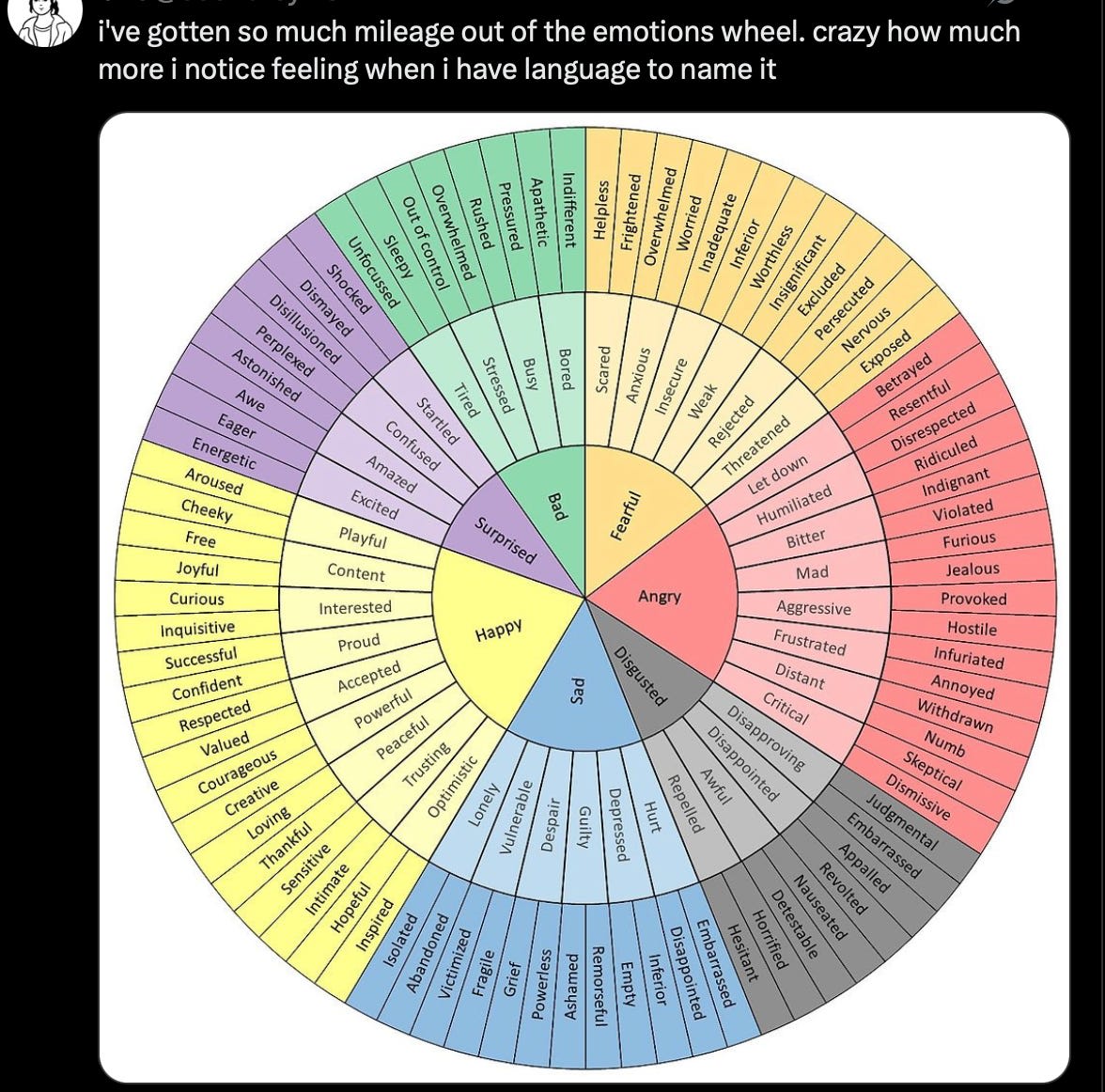

A dimensionalization of emotion. How does it do on Fidelity/Leverage/Complexity?

Summary and Other Considerations

We have dimensionalized dimensionalization into three parts:

Fidelity: how well the axes map to reality

Leverage: what changes when we move along an axis

Complexity: the price we pay to use the model

These meta-dimensions are dials you can tune as you practice dimensionalizing in your own life.

The meta-dimensions do trade off against one another. If you add a dimension to improve Fidelity, you pay for it in Complexity. If you swap an inflexible dimension to one you can modify, improving Leverage, you may reduce Fidelity if the new dimension isn’t causal.

See below for some more considerations, including:

Continuous vs Categorical Dimensions1

Using AI Tools to Dimensionalize2

Add or Remove an Axis?3

Related Terms Across Fields4

Conclusion

Dimensionalization is a lens. It is what smart judgment looks like under the hood.

It’s what you do when you shift from asking “is this good?” to “where is this strong, and where is it weak?”.

It lets you reason instead of react. It lets you compare things that feel incomparable. It helps you optimize without being reductive.

You can try dimensionalizing the next time you need to make a decision, review a meal, or understand a feeling.

Learn to see dimensions as dials. It makes the world editable.

Continuous vs Categorical Dimensions

Categorization says: this is a drama, that is a comedy. Dimensionalization asks: how funny? how tragic? how character-driven? how plot-heavy?

Continuous sliders give you nuance, tradeoff analysis, optimization. Categorical labels are sometimes better for simplicity or communication.

Continuous: Return %, risk level, time to delivery.

Categorical: Genre, cuisine, product tier.

Tradeoffs again! Dimensionalize when it helps. Categorize when it doesn’t hurt.

Using LLMs to Dimensionalize

LLMs can be powerful allies in dimensionalization. You can use them to brainstorm plausible axes in a new domain, rephrase or cluster raw input data into latent dimensions, or simulate how tweaking one variable might cascade through others. LLMs can help extract candidate dimensions, rank them by salience, and even map them onto continuous scales. The key is to treat the LLM not as a decision-maker, but as a dimension-spotter: it helps you surface and test possible ways the world might be sliced.

Try this prompt:

“I am thinking about ______. Dimensionalize it, by identifying dimensions that map to reality (Fidelity), that are in my control (Leverage), and that don’t overfit (Complexity).”

Then you can try:

“Now rank the dimensions by Leverage”

or

“Try making 10 more and then combining them all into a MECE grouping”.

Add or Remove an Axis?

Adding an axis is only worth it if:

It explains variance not captured by others.

It changes the ranking of options.

It lets you make a better decision.

Otherwise, it’s a shiny distraction. Often you are better off combining dimensions to reduce Complexity at the potential cost of Fidelity.

Related Terms Across Fields

Different domains name the same move differently:

English (Subtlety): Balancing conflicting effects—tone, pace, diction—without maxing any one.

Machine Learning (Featurization): Choosing axes of input variation that shadow causality.

Parenting (Maturity): Seeing and balancing many developmental needs instead of maximizing a single virtue.

Software Engineering (Architecture): Designing around modularity, latency, scaling, cost.

Art (Composition): Spatial arrangement of elements with rhythm, emphasis, balance.

Exercise (Periodization): Coordinating training variables across time—intensity, recovery, volume.

Spirituality (Integration): Weaving together mindfulness, ethics, discipline, insight, and grace into a practice.

These are all examples of dimensionalization in domain jargon.

I make music videos and my decision I often make poorly is:

How would you dimensionalize this decision?

Off the top of my head some of the low-leverage dimensions would be the standard metrics like views, like, even reshares. Others might be “timeliness” of the actual content (i.e. what current trends it is very mindful and demure of), and “ethos” which might also be called how “on brand” it is—which I breaks into it’s own series of dimensions.

However in my case the real leverage is: “does this solicit me more music video commissions?”

I’ve tried in the past to break this down into broad categories of dimensions like:

But like… none seem to have any leverage. What in my approach am I doing wrong?

Hi—I love the question.

First, it matters what you choose to dimensionalize: “Dimensionalize Posting Instagram Content” will give you different results from “Dimensionalize Soliciting More Commissions”. And “Dimensionalize Posting Instagram Content with respect to its impact on Soliciting More Commissions” will give you still different results. The key is that dimensionalization tries to give you levers to affect a specific decision or outcome.

Second, I strongly recommend using LLMs to help you dimensionalize. Without domain expertise in these areas, I am not going to provide much edge vs an LLM. You can take your comment, paste it into an LLM, link to this post, and ask for dimensionalization of whatever you want using this framework. Part of the goal of the post is to make it easy for me (and others) to do this :)

Here’s an example, straight from o3:

You can then ask for candidate videos (or provide your own) and have the LLM rank by dimension:

If you don’t like the dimensions or the examples, you can ask for new ones, or pick a different choice to dimensionalize.

Hope this is helpful!

Thank you for the extensive reply, however it still leaves me in the dark of how to spot a dimension that actually provide leverage. In your post you gave several examples of leverage, that’s a start, but what I was hoping for was a narration of the thinking process that lead to those examples that can be applied to many different situations.

One example you give of what is not a lever is:

This seems rather intuitive since it seems like window dressing in the same way that the color of your shorts is a dial that doesn’t matter. However it still doesn’t illuminate which dials do matter and how to find them. I would love to have you deep dive into that across three different domains and then show what commonalities exist between them so that as an exercise for the reader they can apply it to others.

There’s no end to dials that don’t matter and I find LLMs are particularly guilty of providing platitude-laden, non important dials, vague, or irrelevant (celeb tags? Who am I? Hailey Beiber?)

Thanks. Here’s what I would suggest if you want to do Dimensionalization by hand starting with Leverage:

Start with actions you can take, and filter for those that would result in things that matter to your outcome. Or,

Work backwards from things that would matter to your outcome, and filter for those that have triggers that are at least partially in your control.

Then, once you’ve made a list of atomic actions with high Leverage, you can group them in various ways to reduce Complexity and align to your model of ‘how the outcome works’ to increase Fidelity.

FWIW, it feels obvious to me that having celebrities participate in your videos lends credibility (strong social proof) that could lead to additional commissions. Fine if your target commission audience would be put off by this; in that case, you should find audience-relevant signals of credibility. But credibility is probably going to be important regardless of how you achieve it.

Can you give three examples of what that filtering process looks like? Even for things unrelated to my question—having a guide, an example, the thought processes, the heuristics would be invaluable.

And what if I don’t know what matters, hence my ineptitude at finding levers?

The point was it is not a lever in that I do not have access to celebrity participants and don’t know what dials I have to change that. The question wasn’t one of credibility, the question was one of again—how does this manifest as a lever? Again narrative examples of the thought process—how to get there rather than the conclusion reached - would help.

Let’s do one example. Suppose you are trying to get access to celebrity participants for your music videos, since we’ve identified that as high leverage. Let’s start by listing some things that could meaningfully lead to celebrities agreeing to participate:

One of the celebrity’s friends recommends that they work with you

The celebrity sees your video and wants their work treated similarly

Your agent connects with the celebrity’s agent and arranges a quid pro quo

You use archive footage of a celebrity in your video and get their permission after the fact

...

Now we can filter for what is in your control:

You can try to befriend a celebrity’s friends

You can try cold-sending your work to celebrities

You can hire an agent and ask that they help you work with celebrities

You can try to find footage of celebrities who might be amenable to this kind of fair use

...

Of these, hiring an agent strikes me as the most certain way to achieve the outcome.

If we had like 50 options (we can get that by using an LLM), then it would make sense to group them and optimize for Fidelity and Complexity. But for now we are focused solely on a few high-leverage actions and I’m not using an LLM, so I won’t go through the whole dimensionalization process.

If you again find yourself thinking “but I can’t befriend a celebrity’s friends” or something like that, you can just do the exact same exercise to dimensionalize that outcome.