The internet makes it easier to cooperate. That is a simple way to explain what is happening to our society and politics.

Internet technology has progressed by adding layers. In the 1970s, the Internet itself let different computers anywhere in the world communicate with each other. In the 1990s, the World Wide Web added a layer on top of this, which let humans publish their ideas on a web page. In the 2000s social media added new layers, allowing people to reply to each other, share information with their friends, and upvote what they liked. Other apps link these capacities to the offline world. On Kickstarter, people can coordinate to provide seed funding for firms or projects. On Meetup, they can pick a time and place to meet physically. NextDoor links online conversation to real-world neighbourhoods. A unifying theme of many of these new layers is: they make it easier for people to come together to solve problems.

There’s no reason to think this process is finished. For example, we still don’t yet have truly convenient ways to pay each other. It’s easy to pay a company, yes, but not yet trivial for any two people to make a payment via a phone. Apple is moving in that direction. Cryptocurrencies are payment systems that do an end run around State fiat currencies. Easy payments will yet further extend people’s ability to cooperate.

If this all sounds cheerful, why then is politics so chaotic and troubled?

1. Cooperation is not always socially good.

2. Making cooperation technically easier still only allows some people, not everyone, to cooperate.

Cooperation benefits the cooperators, by definition. But it often does so at outsiders’ expense. Cartels cooperate to fix prices. This transfers money from consumers’ pockets to theirs, and as a bonus has deadweight costs which just make everyone worse off. People can cooperate to threaten violence: states originated as gangs cooperating to dominate others and/or defend against other gangs. Or they can cooperate to lobby politicians for policy changes that benefit them. Mancur Olson (a hero of mine) thinks of politics as an arena which is intrinsically biased towards small groups who are capable of cooperating. As my PhD supervisor used to say: the European Union has a Meat Producers’ Association, but no Meat Eaters’ Association.

If the internet made it easier for everyone to cooperate, point 1 wouldn’t matter. When everyone has a place at the table, people can always agree on a solution that’s best for everyone, as Ronald Coase pointed out. This is the techno-utopian vision of the internet as a vast collective brain which argues its way to the best possible world.

But there are many reasons why cooperation is hard, and the internet only fixes some of them. It makes it technically easier to cooperate, by making communication and contracting easier. As a result, the internet benefits those groups for whom only the technical constraints were binding. Relatively, it disadvantages other groups.

Who wins when you unbind the technological constraint? Numerous, geographically diffuse, ideologically united groups.

Numerous groups win because before, it was too hard for them to communicate. Small groups — oligopolists, government ministries, the people who meet at Davos — could already work face-to-face. Today, legislatures find it easier to cooperate against executives. I’ve been surprised by how hard a ride Boris Johnson has had in Parliament, not because he doesn’t deserve it, but because previous governments with 80-seat majorities have essentially had the whip hand. Now, backbenchers with a grievance can work together much more easily: any WhatsApp group can start a rebellion.

For the same reason, geographically diffuse groups win. Marx pointed out that capitalists dug their own grave by bringing working men together in the factory, where they could learn to trust one another. As this kind of manufacturing declined, unions lost power. Now, tech has relevelled the playing field. Without ever needing to meet in person, Deliveroo drivers can unite, and to stop them unionizing, Deliveroo had to fight in the courts.

Ideologically united groups win because they know what they want. Marxists, reactionaries, and others on the fringe of the political compass were confined to small, passionate cliques. Now they can form mega-cliques on Twitter or Reddit. This is the political version of what some dude on the internet called the toaster fucker problem.

Man wakes up in 1980, tells his friends “I want to fuck a toaster”. Friends quite rightly berate and laugh at him, guy deals with it, maybe gets some therapy and goes on a bit better adjusted.

Guy in 2021 tells his friends that he wants to fuck a toaster, gets laughed at, immediately jumps on facebook and finds “Toaster Fucker Support group” where he reads that he’s actually oppressed and he needs to cut out everyone around him and should only listen to his fellow toaster fuckers.

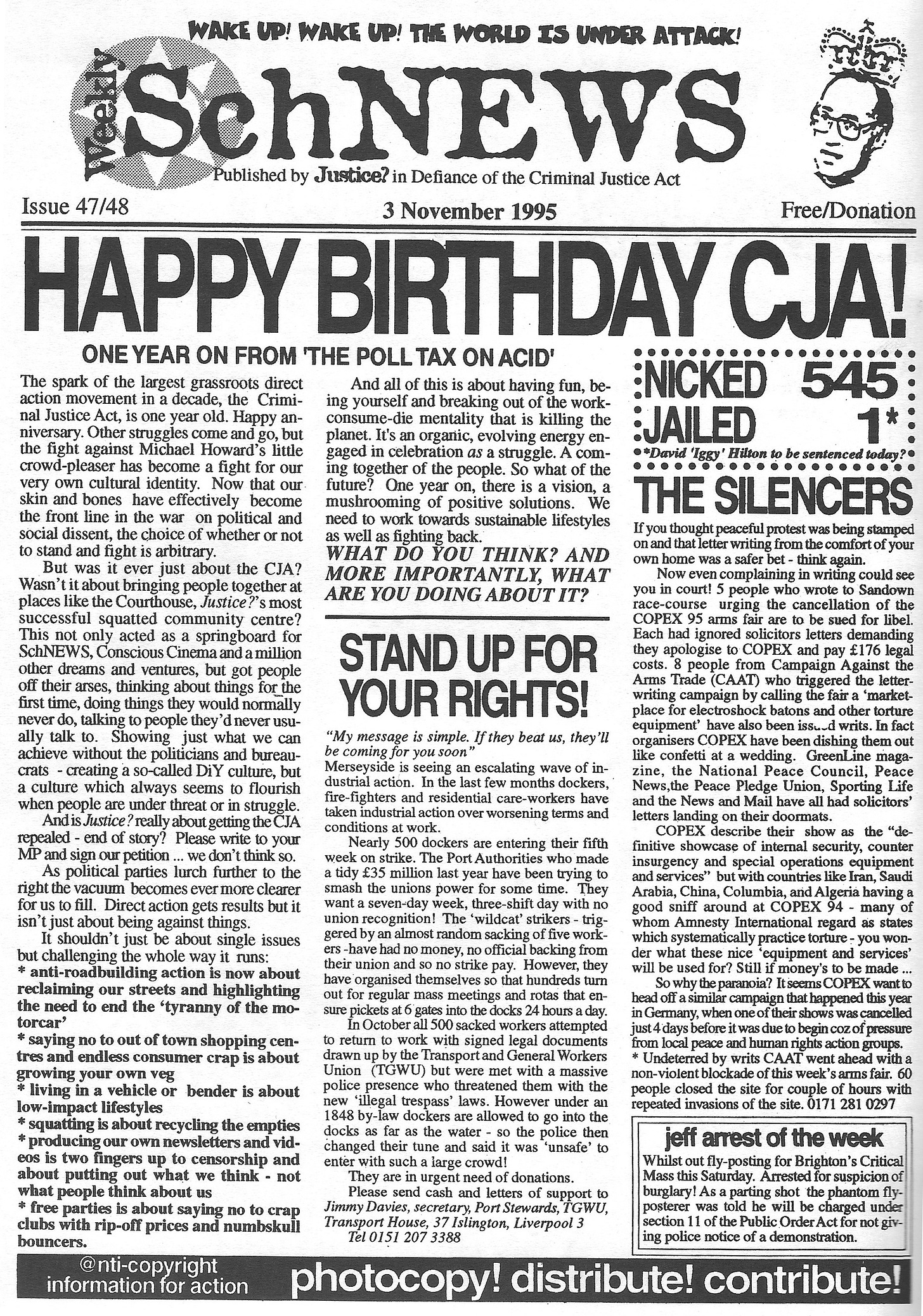

If you’re an anarchist in 1995, you’re printing Schnews and handing it out at festivals. An anarchist now can talk to a million anarchists without leaving his keyboard. Religious extremists win for the same reason.

Thinking about technology helps us understand the turn politics has taken. Twenty years ago the mainstream right was libertarian. Left-wing government was bad because it interfered with people’s freedoms. The right today just thinks left-wing government interferes with the wrong people’s freedoms. It wants that power for itself. We could blame ideological change. But tech is higher up in the causal chain. Cooperating to expropriate others, whether by theft, intimidation, guilt-tripping, legal extortion or political lobbying, has got much easier. Our politics just reflects that. Much of contemporary politics is about getting people together to snatch stuff, under the guise of whatever norm, ideology, meme or slogan will do the trick.

Whole nations can also win from the unbound technological constraint, when the mood takes them. Western governments still have not done enough to support Ukraine, but they have done extraordinarily more than I would have expected, and one reason is that they enraged the hive mind of the Western internet.

These flashes of popular enthusiasm cannot last forever, but when they emerge they can “shift the equilibrium” in politics. Sometimes, technology still unites people.

More often, though, the popular mood is a resource to be fought over, not an actor in itself. Public opinion in mass democracies is intrinsically fickle, because it is not reliably linked to any outcome. In politics, you really can think what you like. There are no penalties for being ill-informed or deluded. As a result, mass opinion can fixate upon issues that are intrinsically trivial: let’s get angry about trans people in sports! Or it can be swayed by clever manipulation. The unbound technological constraint has massively increased the payoffs for this kind of tomfoolery. As Kenneth Mars puts it in Young Frankenstein: “a riot is an ugly thing… but I think it’s just about time that we had one!”

Much ink has been spilt on the various human biases that might underlie our angry, divided politics. But you can’t explain change by a constant. Human psychology was the same in the 1990s, when political apathy was the problem we all worried about (innocent times!) What has changed is communications technology. A new world has emerged ready for use. I think we need a pretentious quote here: flectere si nequeo superos, Acheronta movebo. “If I can’t shift the powers above, I’ll raise Hell.” Freud put that on the frontispiece to The Interpretation of Dreams. It’s a nice description of what modern politics is like, and Western democracies — and maybe other political systems too — need to learn to live with it.

Isn’t this more about coordination rather than cooperation? In game theory, cooperation is specifically about doing a nice thing for someone else.

I’d argue that in game theory, cooperation is an arbitrary label placed on the rows/columns that the researcher wants to bias the reader for. In some cases, it’s used to indicate the rows which are greater total payout even with lower individual payout for some, again as a bias inducer rather than as a defined term which is part of the analysis.

Regardless, the original post is correct in it’s use. “cooperation” can be among a subgroup, even if it’s antagonistic or lower-value to other subgroups or the naive sum of the whole.

I mean, this isn’t a big deal either way, but I suspect that the exposure of the median LWer to game theory consists primarily of the prisoner’s dilemma, where “cooperate” is the standard name for one of the two actions.

I also wondered something like this when reading, but this felt like a bad reason to use the term. But, well, it really just comes down to what you associate with the term.

I think that’s a weird take. A cooperation game typically has actions where you lose, but others gain more (whatever actions others take). Prisoner’s Dilemmas and public goods games are simple examples. The only wrinkle is “what counts as more” if you take seriously the idea that utility is non-comparable across persons. But a weaker criterion is just “everyone would be better off if everyone cooperated”, which again the PD and public goods games satisfy.

You’re right. I didn’t distinguish between the two concepts, because I think cooperation in the colloquial sense – working together for a shared goal – typically involves elements of both.

At its simplest, the internet makes communication easier, especially public communication. That should certainly help to solve coordination problems. It’ll also help solve cooperation problems insofar as (1) communication shapes preferences; (2) people are susceptible to social norms, and communication helps to spread norms, clarify them and make them salient; (3) people can coordinate on structures which enforce cooperation, e.g. punishment for non-cooperators. Examples of (3) might be non-cooperators getting “cancelled”, or e.g. consumer boycotts of firms who exploit labour unethically. And of course, points 1-3 can all also be (ab)used to enable bad kinds of cooperation.

From Neal Stephenson’s Diamond Age:

> For example, we still don’t yet have truly convenient ways to pay each other. It’s easy to pay a company, yes, but not yet trivial for any two people to make a payment via a phone.

It’s kinda funny that in Russia (where I live), that is relatively poor, not very technologically advanced, pretty authoritarian country… it actually is trivial.

Very nice read. One aspect I find fascinating is how international political movements might be effected. One reason nations are defined by borders geographically is that coordination used to be constrained by distance. But that is less and less the case, for example, New Zealand’s anit-lockdown protests were described as “imported” from Canada (“inspired” would probably be more accurate). I think nations will stay geographical, but perhaps something in their character will change. Policies need not just catch “the national mood” but perhaps the international one. For myself, a week after Joe Biden’s election victory Boris Johnson looked like a political dinosaur from a previous insane age. A week before he had looked like a symptom of the times.

I think language barrier is substantial for now and New Zealand and Canada sharing English language is an exception.