With the weakening of the trans-Atlantic alliance, the debate over European integration has entered a new phase. Mario Draghi warns that Europe risks becoming “merely a large market, subject to the priorities of others,” a collection of middling states in a world where the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must. Facing the U.S. that views European fragmentation as advantageous and a China willing to exploit its supply chain dominance, Draghi calls for adopting a pragmatic federalist stance.

Similarly, in this article, Ricardo Hausmann draws on XIX. century history to argue that Europe faces the same challenge Italian and German nationalists once did: building a political community across diverse populations. As Italian statesman Massimo d’Azeglio said after unification: “We have made Italy; now we must make Italians.” The EU has created economic integration but lacks the political identity necessary to command devotion and loyalty to the new political entity.

Stefan Schubert counters that this analogy doesn’t hold. Europe today is fundamentally more diverse than the territories that once became Italy or Germany.

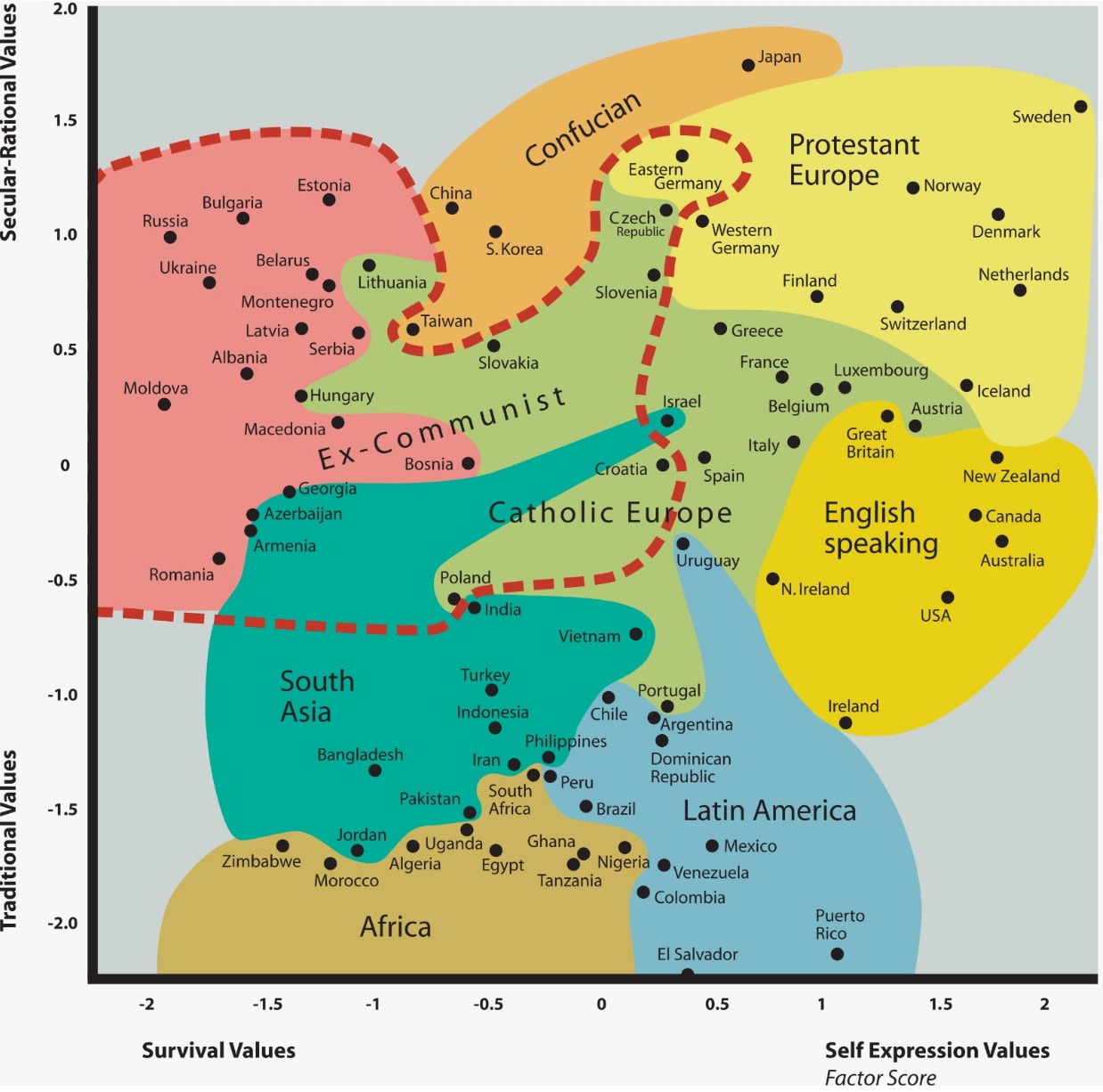

The EU has 24 official languages where Italy or Germany had one. World Values Survey data shows cultural variation within Europe exceeds that within the U.S., China, or India. For example, views on fundamental questions like sexual consent vary dramatically across the continent. Economically, Denmark’s per capita GDP is vastly greater than Bulgaria’s.

The skeptics have a point. Modern Europe is quite diverse. Yet, contrasting it with the countries that unified in XIX. century—Germany, Italy or Switzerland—doesn’t really work.

Consider the language question.

Most people in pre-unification Italy couldn’t speak standard Italian. Only about 10% could and maybe a half could even comprehend it. What we call “Italian dialects” would, without the hindsight of unified Italy, be considered separate languages. Many evolved from vulgar Latin independently, much like Spanish or French. They’re often mutually unintelligible, and Sardinian may even constitute an entirely separate branch of Romance languages. In short, Italians could barely understand each other.

Germany was no different. A Plattdeutsch-speaking artisan from Lübeck could hardly understand a Swabian peasant. A burgher from Munich would have had a hard time understanding a burgher of Strasbourg.

Switzerland presents an even starker case. Where proponents of Italian or German unity could at least pretend a common national language existed, Switzerland had no such luxury. Any attempt to promote German at the expense of French or Italian would have only sparked unrest. Yet Switzerland unified anyway.

Today’s Europe, by contrast, has a significant advantage: many Europeans, especially younger ones, can communicate in English, a lingua franca far more widespread than standard German or Italian ever were in the XIX. century.

Or consider different political systems.

Both pre-unification Italy and Germany encompassed a bewildering variety of governmental forms. Germany had everything from authoritarian monarchies, where the king held near-absolute power, to constitutional monarchies with elected parliaments, to the republican traditions of the Hanseatic and free cities.

Italy was, if anything, more diverse. The peninsula contained absolute monarchies like the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, constitutional monarchies like Piedmont-Sardinia, the theocratic Papal States, with large swathes of territory occupied by Austria.

Switzerland takes political diversity to another level entirely. Some cantons were ruled by a patriciate or by guilds. Some practiced forms of direct democracy in rural assemblies. Other territories were subject lands with no political autonomy whatsoever. Graubünden operated as a kind of anarcho-communal confederation, with self-rule devolved to the village level. And then there was Neuchâtel, which was simultaneously a Swiss canton and a principality ruled by the King of Prussia. Go figure.

By comparison, today’s EU is remarkably homogeneous. Every single member state is a liberal democracy with free elections, independent judiciaries, protection of fundamental rights, and market economies. If you dig into the details, the similarities deepen: with the exception of France, nearly all use some form of proportional representation in their electoral systems. The political spectrum in each country differs, but the basic constitutional framework is essentially the same. The EU has never had to reconcile absolute monarchy with republicanism, theocracy with secularism, or feudalism with democracy. The political distance between Warsaw and Lisbon is trivial compared to the distance between, say, Kingdom of Saxony and the Hanseatic city of Hamburg.

The GDP argument is more complex. It’s true that Denmark’s per capita GDP is nearly twice Bulgaria’s. It’s also true that economic disparities were much smaller in the mid-XIX. century. The reason, of course, is industrialization and its agglomeration effects. Once it happened — and that was mostly after the period of unifications — it accelerated some regions far ahead of others.

One could therefore reasonably argue that XIX. century unifications were possible precisely because these differences hadn’t yet ballooned, and that the window of opportunity has since closed. We now live in a world that is not conducive to unification.

Yet there are signs pointing in the opposite direction.

First, regional differences within states are substantial. Lombardy is 2.3 times wealthier than Calabria, a difference similar to that between Denmark and Bulgaria. Yet separatist movements remain marginal. The Lega once championed independence for Northern Italy but has largely abandoned such demands. Catalonia’s independence movement, despite its prominence, has failed to achieve its goals. Wealthy regions, it seems, are not actually leaving their poorer partners.

Second, the same pattern appears at the EU level. Simple zero-sum logic would suggest a sorting process: poor countries join to access transfers, rich countries leave to avoid paying them. We should see the EU gradually moving eastward and becoming poorer. Yet with the single exception of Brexit — a departure that has served mostly as a cautionary tale — this isn’t happening. The accession process for the poor countries in Balkans stalls and despite occasional posturing and threats, no wealthy member state is seriously pursuing exit.

This doesn’t indicate much enthusiasm for unification, but it does suggest that despite real centrifugal forces, there are counterbalancing centripetal forces at play, and that they may be stronger.

At a more practical level, were the pre-unification countries more economically integrated than the EU member states? Pre-unification Germany had its Zollverein, which was a great improvement over the previous system, but in no way compared to the scale of economic integration seen across the EU today. Italy and Switzerland, on the other hand, had no economic integration to speak of.

Finally, cultural differences present perhaps the most intuitive objection to European unification. How can people from such different traditions form a genuine political community?

In the XIX. century, culture was exceedingly localized. Most people rarely traveled beyond their native village or town. This remained true even much later. My grandmother in Slovakia, well into her seventies, used to recall an incident from her youth in the early 1940s when she traveled to attend a wedding in a neighboring valley. For her, this journey was a unique adventure, an expedition into foreign territory.

Today’s Europe is different. You can hop on a Ryanair flight and travel to the other side of the continent for mere €25. People move freely across borders as part of everyday life. In Bulgaria, let’s say, approximately 20% of the population lives and works abroad, predominantly in other EU countries. And this isn’t just the case for Bulgaria. Across Europe, virtually everyone either has lived abroad themselves or has close friends and family members who have.

Moreover, this isn’t an elite phenomenon limited to cosmopolitan professionals. Visit a Slovak village and you’ll find that men have often worked construction in France or Germany. Women have worked as nurses in Austria or caregivers in Italy. At a somewhat more elite level, the Erasmus program has facilitated cultural exchange on a large scale. Since its inception, roughly 16 million people, about 3% of Europe’s total population, have lived and studied abroad. The number rises each year by 1.3 million. At the most elite level, the cosmopolitanism is simply a given. One attends regular videocalls with colleagues and business partners in other countries or flies around to meet them in person.

Meanwhile, globalization amplifies these effects. Estonian and Portuguese teenagers watch the same YouTube videos. They follow the same TikTok feed. Berliners still eat their currywurst, but they are equally familiar with McDonald’s as their Romanian counterparts are.

One might object that these are superficial similarities. People may all drink Coca-Cola and watch Marvel movies, but does this really change fundamental attitudes about family, authority, or social organization?

The evidence suggests it can. Consider a study on the impact of Brazilian telenovelas on fertility rates. Researchers found that as television coverage expanded across Brazil, bringing telenovelas into new areas, fertility rates declined substantially in those regions. The programming consistently portrayed smaller, more urban families with fewer children. Viewers, even in remote areas with very different traditional family structures, adjusted their own fertility decisions in response.

In short, common people in pre-unification Italy, Germany and Switzerland lived in cultural isolation. Europeans today, whether they like it or not, do not.

All of this doesn’t mean that Eunification would be easy or even possible. However, it does show that the argument that the future European countries in the XIX. century were more homogeneous than the EU member states are today and were thus easier to unify, does not hold water. The diversity that seems insurmountable today is not qualitatively different from what earlier state-builders successfully overcame.

Looking at the data collection, region and country are fairly straightforward, but “Europe” could mean a wide variety of things to a wide variety of people, meaning that the identification numbers might overestimate attachment to the EU as a political structure. Someone might feel attached to the historical Europe, as a cultural and technological force, yet not consider the EU to be meaningfully connected to it.

More directly, I think the core issue that the EU faces is that of interests. Every strong or rising power today can point to a clear set of interests motivating its base of power (usually a majority of citizens) to support it:

The PRC can advertise that it has made its citizens wealthier by facilitating nation-wide industrialization and negotiating trade agreements that have greatly increased living standards. Likewise, it can point to China’s pre-PRC experience under the influence of foreign powers, and the more recent experience of some nearby countries, to claim that this newfound wealth isn’t possible without a strong central government to keep other powers from using the threat of force to rent-seek. Moreover, the PRC can claim that the interests of China are the interests of the overwhelming majority of its current citizens’ descendants—even if they happen to live elsewhere.

Russia can point to the early post-Soviet years as an example of what happens when there isn’t a strong, independent government serving as a check on foreign investors and local oligarchs. Moreover, there is certainly a perception—starting with the Bush administration appearing to spurn early attempts at reconciliation - that the U.S. has committed to being an enemy of Russia, and that without central coordination of resources to deter them, they would forcibly bring back the bad old days of state-permitted looting of everything not nailed down by anyone with a carpet bag full of money. Also, as with the above, it is generally understood that people can be intrinsically Russian regardless of their citizenship, and that their fates are intertwined with the fate of the Russian government. <Backlash / Discrimination, depending on your political leanings> against overseas ethnic Russians post-2020 has cemented this.

America, in part due to ongoing polarization, has two separate proposals to two somewhat-separate bases of power.

To a degree, it is still a nation-state, and can claim that a wealthy America provides opportunities for people who are descendants of the historical American nation. This is a bit less intense than in the above two countries, since these Americans could renounce citizenship and become a fully-assimilated Australian/Spanish/Austrian within the span of one generation, if so inclined, but there is still a perception that the umbrella of American hegemony provides leverage to ordinary citizens. It’s this perception that keeps the pointy end of the U.S. military well-staffed.

The second proposal is as a somewhat international collective of elites, where they can come together to make sure the world remains a good place to do business, and negotiate with “rogue” actors from a shared position of strength. Everyone can attend the same fundraisers, invest in the same companies, and send their children to the same universities to network with each other. Notably, it’s this perception that allows the U.S. to arrange things like the stand-down that enabled the <Arrest / Kidnapping, depending on your political leanings> of Maduro by appealing to local elites who might want their kids to go to Harvard.

A shared language and some cultural overlap isn’t enough to create a nation—there have to be shared interests that motivate people to be willing to work and fight in the interest of the collective.

From what I’ve seen, there is a core political class in Europe which serves as the EU’s base of power and is glad to provide it with support in exchange for coordinating the funding of friendly NGOs and helping to oppose non-aligned political movements, but this is a relatively small group that does not enjoy universal popularity. To meaningfully counterbalance America, Russia, and China, there would need to be a common cause that a large number of people are willing to go above and beyond for—the sort of thing makes workers do more than they’re paid to do and makes soldiers willing to fight rather than rout. The usual motivation is something along the lines of “This nation is the exclusive property of all of your descendants, forever, and the blood and sweat you invest will never be lost to them”, but the Venn diagram of people advocating that for Europe and people who support the EU is very close to two nonintersecting circles.

I think we can overcome most of the cultural differences you mention. In my lifetime we have become noticably more culturally united and I believe the kids who grow up today will be culturally more or less the same across Europe.

A much bigger impediment to European unification is instead something you don’t talk about namely the different political cultures in Europe, including such things as the level of tolerated political corruption.

These differences are also shrinking but there is still some ways to go, I think.