Linked from my Substack

Research is expensive, especially these days. Even though grad students and postdocs are underpaid, it still costs a lot to employ them.[1]

And every year, lab suppliers increase their prices. Overall, it continually gets more expensive to do the same amount of work:

Therefore, in order to carry out my meiosis project, I needed a source of funding. I am just a grad student and usually it is a professor’s job to get grants, but for various reasons I decided to take matters into my own hands.

After my experience with the F31 fellowship and all its paperwork, I was rather turned off by the prospect of applying for an NIH grant (R01 or R21). In the best case, I would have to write a huge application, then wait for months before hearing if it was funded, then more months before actually being able to spend anything. And of course, funding chances are always low with the NIH.

So, I decided to seek out private philanthropic funding. This, as it turned out, was not as simple as I had expected.

Timeline of events

September 2022

I develop my project idea and figure out roughly how much funding I need ($300,000 per year over two years, to cover salaries and lab supplies).

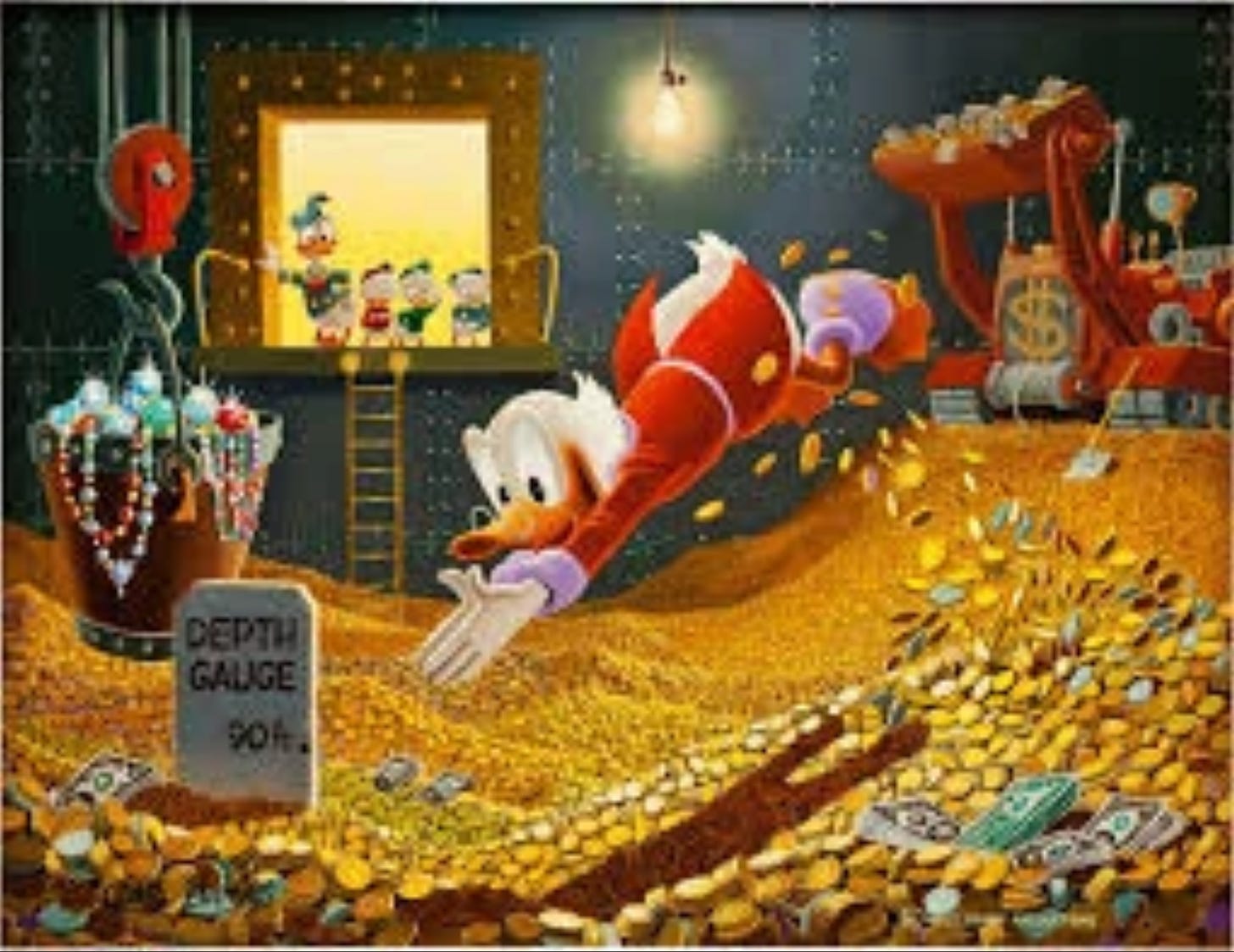

I reach out to some potential funders. I quickly focus on the FTX Future Fund, since they are known to have a giant pile of cash they want to get rid of.

October 2022

I write a formal research proposal and submit it to some FTX Future Fund regrantors.[2]

I also start meeting with some university admins who manage research finances. They agree that we can set the overhead rate at 15%.[3]

October 29: I meet with the regrantors who tell me they are excited about the project.

November 2022

November 3: The FTX Future Fund regrantors announce that they’ve approved the grant, and can I please send them my bank account info for them to wire $300,000?

But before we can accept the funds, my university needs to do due diligence to make sure they’re not criminals.[4]

The Jeffrey Epstein scandal created some strong organizational scar tissue. Perhaps this is a good thing, because . . .

November 8:

November 14: It’s confirmed that I won’t be seeing a cent of the $300,000 from the FTX Future Fund. Well, at least I am not at risk of clawbacks.

Late November: I meet with various other philanthropists, and receive multiple suggestions to apply for a Survival and Flourishing Fund (SFF) Speculation Grant. I start working on the application.

November 17: The Repro Grants are announced. This seems like a perfect fit for my research.

November 20: I submit my initial Repro Grant application. Overall I spent about 6 hours writing it (they claimed it would take 30 minutes, but it’s certainly better than the 100 hours I spent on the F31).

December 2022

December 7: I hear that my initial Repro Grant application was not funded. However, there is still time left in the application period, so I spend another ~6 hours writing a different proposal (focusing on ovarian organoids instead of meiosis).

December 22: I submit my application for a SFF Speculation Grant. Around this time, I am also discussing the project with two private donors who may be interested in funding it. One of these backs out (due, I think, to losing money in the crypto downturn), but the other one is very excited about it.

December 29: SFF agrees to provide $401,000 for the project, with the private donor also providing $300,000. This is at the high end of my requested budget, so I am especially happy about it.

January 2023

January 3: The Repro Grant was funded! Although they only gave me $65,000 out of the $100,000 I requested, it’s still excellent news.

Early January: University admins agree to accept the money from SFF and the Repro Grant. However, they will need to “process” it before I can actually spend anything.

February 2023

University admins are still working on “processing” things. Not much happens that’s visible to me. One item of debate is whether the money should be classified as a “grant” or a “gift”. These are handled by separate administrative teams. It is decided that the $300,000 from the private donor is a “gift” but the $401,000 from SFF is a “grant”. Of course, this creates nearly double the bureaucratic mess.[5]

March 2023

My university admins still haven’t accepted the ReproGrant.

I hear from the admins that, in addition to the negotiated 15% overhead rate, they are planning to charge a “facilities fee” and deduct it from my available funding. They initially estimate that the fee will be $90,000 per year. After I complain a lot, this is decreased to $76,000. I am quite mad about this, especially because my department got a $350,000,000 gift a few months ago to support the facilities.

April 2023

The admins still haven’t accepted the ReproGrant, despite being pestered by multiple emails from me and the ReproGrants people. They are almost done processing the $300,000 gift portion of my funding, so I might actually be able to spend it soon. As long as they finish processing the rest before my this runs out, I will be OK.

In other news, my university receives $300,000,000 from a deep-pocketed donor.

Clearly they will use it to hire more admins.

Pros and cons of private vs. government funding

Based on my experience applying for an NIH grant I can now compare this to my experience getting private funding.

Pros of government funding:

Applications and award terms are standardized

Your university administrators are used to processing these grants and have no excuses to put up obstacles. I actually got a lot of help from some of the administrators at my department (although these are different people than the ones who handle non-government grants).

Government grants are more legible in terms of academic prestige

Cons of government funding:

Applications have tons of paperwork

Low chances of funding

Long time between application and hearing the results

Review panels can be less tolerant of unconventional research

Pros of private funding:

Easy applications

Faster turnaround time. I got notified that my first Repro Grant proposal was not funded about 3 weeks after I submitted the application. Since the application period was still open, I submitted another proposal which did get funded.

Possibly higher chances of funding, if the philanthropists are excited about your research

Cons of private funding:

Award terms are not standardized, which creates more opportunities for university administrators to extract overhead.

Funding may randomly disappear.

It can be hard to find donors who want to fund you.

There may be communication problems between donors and university admins.

On university administrators and their incentives

The large administrative staff at my university is an example of an inadequate equilibrium. Since there are so many administrators, they must charge high overhead rates to pay their salaries. But in order to make the high overhead rate seem justified, the administrators need to do a lot of paperwork, meetings, and other activities requiring a large staff.

At my university there are enough administrators for them to continually “pass the buck” when I ask them to do something. For example: “oh, we don’t handle that, that’s the XYZ Office’s job”. Also, this means I’m still not sure who exactly is in charge of “processing” my funds.

Despite my best efforts, I’ve already been sucked into several hours of meetings, and at the end of each, the conclusion was “we need to have another meeting”. In one of the meetings, an administrator told me, “Your grant isn’t worth our time, we’re looking for people to bring in at least $20,000,000”.

The overall result is that the interests of the donors and researchers are aligned, but the administrators become a barrier between them. And the toll to get money across this barrier is quite high. In the case of government grants, the overhead rate is negotiated ahead of time. With private donations, the university and the donors will argue about the rates. Unless the donor or foundation takes a strong stand (which will slow things down), the adminstrators will end up taking a large cut.

What now?

Despite losing a large chunk of money to “facilities fees”, I still have enough to proceed with the project, albeit with fewer researchers working on it than I had planned. I’ll keep you updated as my research progresses!

- ^

Especially because one needs to pay “tuition costs” to employ a grad student, even when the grad student is taking no classes.

- ^

The Future Fund had so much money, they assigned “regrantors” to give it away.

- ^

To explain overhead rates: the “indirect costs” (i.e. overhead) is charged as a percentage of the “direct costs” (the money I can actually spend). The indirect costs are supposed to cover things like rent on buildings and maintenance for shared equipment.

A 15% overhead rate would mean that for every $100,000 the donor gives me, the donor has to give $15,000 to the university. The overhead rate for NIH grants at my university is 69% (nice). But private foundations are almost always charged a lesser overhead rate; for example, the Gates Foundation has a policy not to pay more than 10%.

- ^

In a separate but amusing instance, they did their vetting on Scott Siskind . . . but they basically just read RationalWiki, took it at face value, and said he had a ton of red flags.

- ^

Another sneaky thing about gifts vs. grants is that gifts nominally have lower overhead rates, but the administrators are free to deduct facilities fees from them, since the donor can’t control how the money gets spent. Grants, on the other hand, have higher overhead rates, but the donor can require that the money actually be spent on research.

Wonder if you could contact the deep-pocket donor and ask them to make their grant conditional on reducing admin overhead.

This is what the 15% overhead rate was about . . . but then my university decided to charge an additional “facilities fee” after receiving the money.

You didn’t get their initial ‘offer’ in writing? Or did they intentionally avoid sending anything on-the-record?

I’m actually surprised considering, as you mentioned, doing paperwork that dots every i and crosses every t is part of the reason for hiring so many administrators.

“Overall, it continually gets more expensive to do the same amount of work”

This doesn’t seem supported by the graph? I might be misunderstanding something, but it seems like research funding essentially followed inflation, so it didn’t get more expensive in any meaningful terms. The trend even seems to be a little bit downwards for the real value.

Grant award amounts remained the same adjusted for the biomedical price index, but the nominal amounts had to double to match the price index increases.

Do you happen to have some quick numbers on hand about this? What’s the overhead?

For example: I make approximately $38,000 a year but it costs approximately $60,000 a year to pay my stipend from a research grant. And this is before overhead rates and facilities fees.

So assuming you are paid of an NIH grant subject to the 69% indirect, that’s ~$100,000 a year?

Right – but the math is a bit different since I have an F31 fellowship.

Congrats!!! By successfully navigating this insane maze you’ve now ‘proven’ that you can obtain funds. You’ll be made to jump through a series of hoops, but assuming your publication history is at all reasonable, you’re pretty much ready for going straight from grad student to PI. I highly highly suggest skipping postdoc hell if you have any chance at all, but if you can’t, just repeat whatever magic you just did and spare yourself the pain of staying there too long. Having your salary go from 36k to ~100k (without passing through the 50k mark) will feel very good.

Good luck with the meiosis project! Rooting for ya!