Introducing Simplexity

“When Charona was trying to explain it to me, she asked me what the most important thing there was. [...]”

″Very good. Anyone who can give a nonrelative answer to that question is simplex.”

- Empire Star, Samuel R. Delany

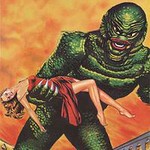

Here’s a small riddle: What do the following three images have in common?

The last picture, which ought be recognizable by readers of the sequences, serves as a clue; so does the quote at the top of the page. But these may be insufficient, so I’ll just put into plain words what ideas these images represent, which by itself reveals part of the answer:

“Human values are so natural that one could very well achieve friendliness in artificial intelligence pretty much by accident, or at least by letting the machines educate themselves, reaching a human (or superior-to-human) respect for life by themselves.”

“The electrons of an atom can be visualized as little tiny billiard balls that go around the nucleus in orbits much like planets go around the sun.”

All three images, therefore, represent different types of fatally flawed thinking that have been directly addressed in past sequences. But this isn’t quite precise, so let me reveal the remainder of the answer as well: These three fallacies can all be said to consist of a very similar pattern of narrow thinking, false fundamental assumptions, and privileged hypotheses.

And this pattern seems so pervasive (in a large multitude of other fallacies as well) that it probably deserves a name of its own.

In Samuel R. Delany’s novella Empire Star, three terms (simplex, complex, and multiplex) are used throughout the novel to label different minds and different ways of thought. Although never explicitly defined, the reader understands their gist to be roughly as follows:

simplex: Able to look at things only from a single, limited perspective.

complex: Able to perceive and comprehend multiple ways of examining things and situations.

multiplex: Able to integrate these multiple perspectives into a new and fuller understanding of the whole.

I will now appropriate the first of these terms to name the above mentioned pattern of biases. It might not be exactly how the author intended it (or then again it might be), but it’s close enough for our purposes:

Simplexity: The erroneous mapping of a territory that occurs due to the treatment of a complex element or a highly specific position or area in configuration space as simpler, more fundamental, or more widely applicable than it actually is.

But because it’s itself rather simplex to think that a single definition would best clarify the meaning for all readers, I’d like to offer a second definition as well.

Simplexity: The assumption of too high a probability of correlation between the characteristics of familiar and unfamiliar elements of the same set.

And here’s a third one:

Simplexity: Treating intuitive notions of simplicity as if referring to the same thing measured by Kolmogorov complexity or used in Solomonoff induction.

These all effectively amount to the same bias, the same flawed way of thinking. Getting back to the images:

In the “Wall-e” picture (which could also have been a “Johnny 5″ picture), we see a simplex view of morality and human values; where such complex systems are treated as simple enough to be stumbled upon even by artificial intelligences that were never deliberately designed to have them...

In the “electron orbits” picture, we see a simplex view of the subatomic world, based on the characteristics of macroscopic objects (like position and velocity) being treated as applicable to the whole of physical reality even at quantum scales.

And lastly, in the “monster and lady” picture, we see a simplex view of attractiveness, based on the personal aesthetic criteria of the artists being treated as applicable to all advanced lifeforms, even ones that have different evolutionary histories.

For those who dislike portmanteus, perhaps a term such as “fake-simplicity” (or even “naivety”) sounds better than “simplexity”. But I think the latter is preferable in a number of ways—for one thing, it helps remind that what starts out seemingly as simplicity (on the human level) may end up as extreme complexity if described mathematically.

Among the differences between simplicity and simplexity is that simplicity can be either in the map or in the territory. Indeed, since as reductionists we believe the territory to be simple at the most fundamental level, a simple map would (all other things being equal) be a better one—simplicity is a virtue.

But simplexity is always in the map: It’s the mind patterning the unfamiliar based on the familiar. Highly useful in an evolutionary sense: humans evolved to be better capable of predicting the actions of other humans than of multiplying three-digit numbers… but ultimately wrong nonetheless whenever it occurs. And the further away from the ancestral environment one gets, the wronger it is likely to be.

And it’s the common basis in cognitive failures that range from The Worst Argument In the World all the way to the just-world fallacy or even to privileging single world hypotheses.

But, lest we seem simplex about simplexity, applying a familiar pattern indiscriminately, this must now be followed by an examination of its different variations...

Next Post: Levels of mindspace simplexity

- 's comment on The flawed Turing test: language, understanding, and partial p-zombies by (17 May 2013 17:36 UTC; 6 points)

- 's comment on Intellectual insularity and productivity by (12 Sep 2012 21:06 UTC; 2 points)

- 's comment on Open Thread, October 1-15, 2012 by (9 Oct 2012 12:02 UTC; 2 points)

A simplex is also a mathematical object which is particularly relevant to some optimization problems. Outside of the context of Empire Star it seems like a mediocre name at best.

They’re square matrices of 150 x 150 pixels.

How comes I didn’t think about that? (The first thing I thought was “I think they all appeared in the Sequences”.)

I think what you call “simplex” is essentially just what the existing English word “simplistic” refers to.

Wall-e: That’s anthropomorphization. It’s not meant to be a realistic depiction of an artificial intelligence, it’s more like the talking animals in The Lion King and countless other cartoons.

Rutherford atom: A reasonable hypothesis once, now a simplified analogy. While it may be misleading when taken at face value, it’s not worthless as an educational tool as long as you make clear that’s an analogy.

Monster and lady: Why are you focusing on the fact that the monster is holding a lady while ignoring the elephant in the room, the gigantic humanoid monster itself? Clearly, again, this is not meant to be a realistic depiction of an alien biological organism, it’s meant to be an allegorical depiction of hostile foreigners (monsters that, stereotypically, “steal our women”).

Even things that aren’t “supposed” to be realistic depictions or projections of likely futures still shape people’s expectations though.

This looks like vocabulary as status rather than vocabulary as communication since I read the post and I’m still not clear on what you mean by the term.

I have a feeling “mindspace” is going to be more of the same.

I’m don’t think this post actually told me anything new, but I upvoted it to encourage the good and engaging use of graphics. The next post will have to have more substantial content to get my upvote, though.

I don’t think the “electron orbits” example counts. Macroscopic objects bipping around with deterministic position and velocity happens not to be how the fundamental building blocks of our universe are put together, but I’d argue that it’s still pretty darn simple. You can write a Newtonian physics simulator in not too many lines of Python.

A Newtonian physics simulator simulates infinitely small conceptual points and/or quantum-cubes in an euclidean space at fixed positions. Not “billiard balls”, AFAIK. I’ve always found the “balls” concept supremely absurd and immediately assumed they were talking about conceptual zero-space point entities.

Otherwise, it seemed very inconsistent to me that the smallest indivisible pieces of reality would have a measurable curved surface and measurable volume (whether physically possible to make these measurements or not). The idea of anything statically perfectly circular or spherical existing in nature was, to my young 13-year-old-mind, obviously inconsistent with the idea that the shortest possible route between two points is a line and that pi happens to be an irrational number (“I mean, infinitely non-regular! How the hell could that happen an infinite amount of times for each surface of a potential infinity of tiny objects bouncing around?!”, would I have said back then). It also seemed like it would fuck up gravity somehow, though I can’t recall the exact train of thought I had back then.

Of course, this is just for the “billiard balls” thing. I agree that it was (and still is in some cases) a very useful model and even the balls make it simpler to explain because it is simplex to most human minds, so on that part I think it’s a fair example. I would, however, have been thoroughly surprised and shaken to learn that it was truly how-things-are that there were tiny literal spheres/balls moving about, rather than conceptual concentrations that represent zero-volume points in space.

There are ways to derive radii of elementary particles—I’m not sure to what extent classical physicists thought these numbers represented actual radii of actual spheres.

How old were you when you learned this part of science? I got the “billiard ball” diagram and analogy when I was fairly young, before I knew a whole lot of science, or the art of questioning what my teacher told me. Looking back, it seems implausible to me to ever “immediately assume” she was talking about “conceptual zero-space point entities”.

After all, isn’t that one reason why some biases and mental images are so hard to grow past? They help form our basis of reality, they’re working deep in our understanding and aren’t easily rooted out just because we’ve updated some aspects of our thinking.

I learned about the actual atomic model, what with how atoms form molecules and all the standard model descriptions, fairly late. I can’t remember the age, but I had already fully learned arithmetic and played a lot with real numbers, and the number zero being what it is, I had already spent a fair amount of time philosophizing over “the nature of nothingness” and what a true zero might really represent, and come to the conclusion that there’s an infinity of “zero” numbers in-between any nonequal real numbers, and as applied to geometry this would translate to an infinity of infinitely small points.

Before learning the actual model as described in classrooms, all my knowledge of atoms came from hearsay and social osmosis and modern culture and various popular medias (TV, pop-sci magazines, etc.)

All I remember was that I had already been told atoms were “the tiny lego blocks of the world” and “so infinitely tiny that they’re impossible to see no matter how big a microscope you make”. From the terms “infinitely”, “tiny”, “impossible”, and “blocks”, and armed with my knowledge about zero applied to geometry, I found natural to infer that the tiny building blocks of the smallest possible size were tiny zero-space points that only have “position” by way of somehow “measuring” their relative distance to other tiny zero-space points. Now that I think about it, that “measuring” term was my first-ever use of a mental placeholder for “THIS IS MAGIC, I HAVE NO IDEA HOW IT WORKS! LET’S DO SCIENCE!”

In retrospect, spending so much time thinking philosophically about the “zero” number and the careless wordings of those that told me about the Atomic Model are probably what made me think this way.

Thanks for sharing. I’m going to have to spend a while trying to envision how that kind of upbringing and pacing would change the way I currently view the world and learn. It certainly seems different from my own. ^_^

You are right in a sense—that example may be somewhat unfair; and actually I originally thought to use a different example, but that one was so messed up that I felt it might require about half a page to describe everything that was wrong with it.

But thing is that even now, after the quantum nature of the subatomic world is known to scientists for many decades, most laymen still imagine electrons like little tiny billiards balls. It’s just easier for human intuition to pattern-match the macroscopic scale onto the quantum scale rather than consider the quantum scale by itself, free of macroscale-preconceptions. It’s just easier for human minds to comprehend macroscopic-style objects...

Moved to Discussion.

You put two words in one and I’m still confused.

Is “The lady down the street is a witch; she did it.” an example of something that is simplex?

Yes, as I understand it. Humans have magical thinking more naturally than causal thinking; ‘Witches’ do ‘magic,’ the sheer fact that the code for “agent defying universal, mathematically simple physics in ways conforming to human expectations” is so short is clear evidence of simplexity.

In that case I believe I understand simplexity.

The world is a complicated place, and reliable generalizations are few and far between.

All three examples seem to fall under the “failure of imagination” category, also known as the Argument from ignorance. Why invent yet another name?

The three examples illustrate less arguments actually stated out loud and more false unconscious ways of thinking. “Failure of imagination” certainly is part of the problem, but as a term it doesn’t really illustrate in my opinion the confusion between human-level intuitive and mathematical notions of “simplicity”, and how that causes a invalid pattern-match that leads to false conclusions...

I don’t see the alien-and-pretty-woman picture as quite representative of either failure of imagination or argument from ignorance. I do think that ArisKatsaris’ notion of “simplexity” is more general than these.

From Wikipedia:

Specifically, “I cannot imagine how anyone could find this girl unattractive, therefore even an alien must find her attractive”.

The orbitals example falls under “appear to be obvious and yet still be false”. So does the FAI one (“good upbringing generally results in good citizenship, so if we educate an AGI properly, it will be friendly”).

Wait, what?

Presumably, any guy out there who is actually going through a reasoning process like what you describes also assumes that all women are lesbians, no? I mean, if they really can’t imagine how anyone could find this girl unattractive, it follows not only that aliens are attracted to her, but that human women are as well.

But it isn’t clear to me that everyone who makes this error also assumes that all women are lesbians.

Therefore it seems there’s something going on besides this sort of argument from incredulity.

At first I was afraid I was petrified at yet another introduction of new jargon, and was going to say as much.

You do have a point. The absurdity metric we [I] commonly confuse with Occam’s Razor does closely resemble “the mind patterning the unfamiliar based on the familiar”, and falsely equating such a resemblance with simplicity. It’s specific enough a mistake to warrant its own name, be it fake-simplicity or “simplexity”.

One of the few times I changed a downvote to an upvote upon reflection. Looking forward to the next post of the series.

Am I the only one that on seeing the title of this post was reminded of this?

Ouch. :-)

This is pretty good. Very insightful, thanks.