ChatGPT is the Daguerreotype of AI

Disclaimer: I work in AI safety and believe we should shut it all down. This post is just some musings on my experience of using AI as a tool.

An expedition

I recently read a book about the rediscovery of the Maya civilization in the 1840s.[1] The experienced adventurers were John Lloyd Stephens, a lawyer and writer, and Frederick Catherwood, an architect and artist. While Catherwood was certainly an artist in the sense of applying creativity towards aesthetic production, his main aim on these expeditions was to accurately record the sites. Their primary goal was scientific, and there was much data to gather.

Their first expedition lasted from 1839 to 1840, and Catherwood brought back numerous drawings. These were then converted into engravings that could be printed into Stephens’ books about their travels. These drawings are so accurate that you can go to the same Maya sites today and correlate each little carved feature of the stelai and lintels. They’re even accurate enough that the Mayan glyphs that appear in them can be read by modern Mayanists.

But Stephens and Catherwood knew they had only scratched the surface of the ruins, and so they soon decided to embark on another expedition in 1841. The book ended a chapter with this teaser;

And this time, they would carry with them an unusual apparatus… Technologically, they were on the cutting edge. This time they hoped to bring back more than words and drawings.

When I read this, I thought about the date and then the relevant historical facts clicked in place for me. I thought, oh! They’re going to bring a camera!! They’re going to take photographs of the ruins!

But then, I noticed my confusion. I’d read the wikipedia pages for these guys, and I’d already flipped through the many illustrations in this book. And I hadn’t seen any of their photographs of the ruins. If they existed, surely I would have? The book was constantly describing the logistical difficulties of the journey; perhaps the camera got lost or broken, dashing their hopes for photographic data capturing.

Photography is hard

As it turns out, the camera did get smashed on the trip, but not before they produced several useful images. So what’s the explanation for why I hadn’t seen them?

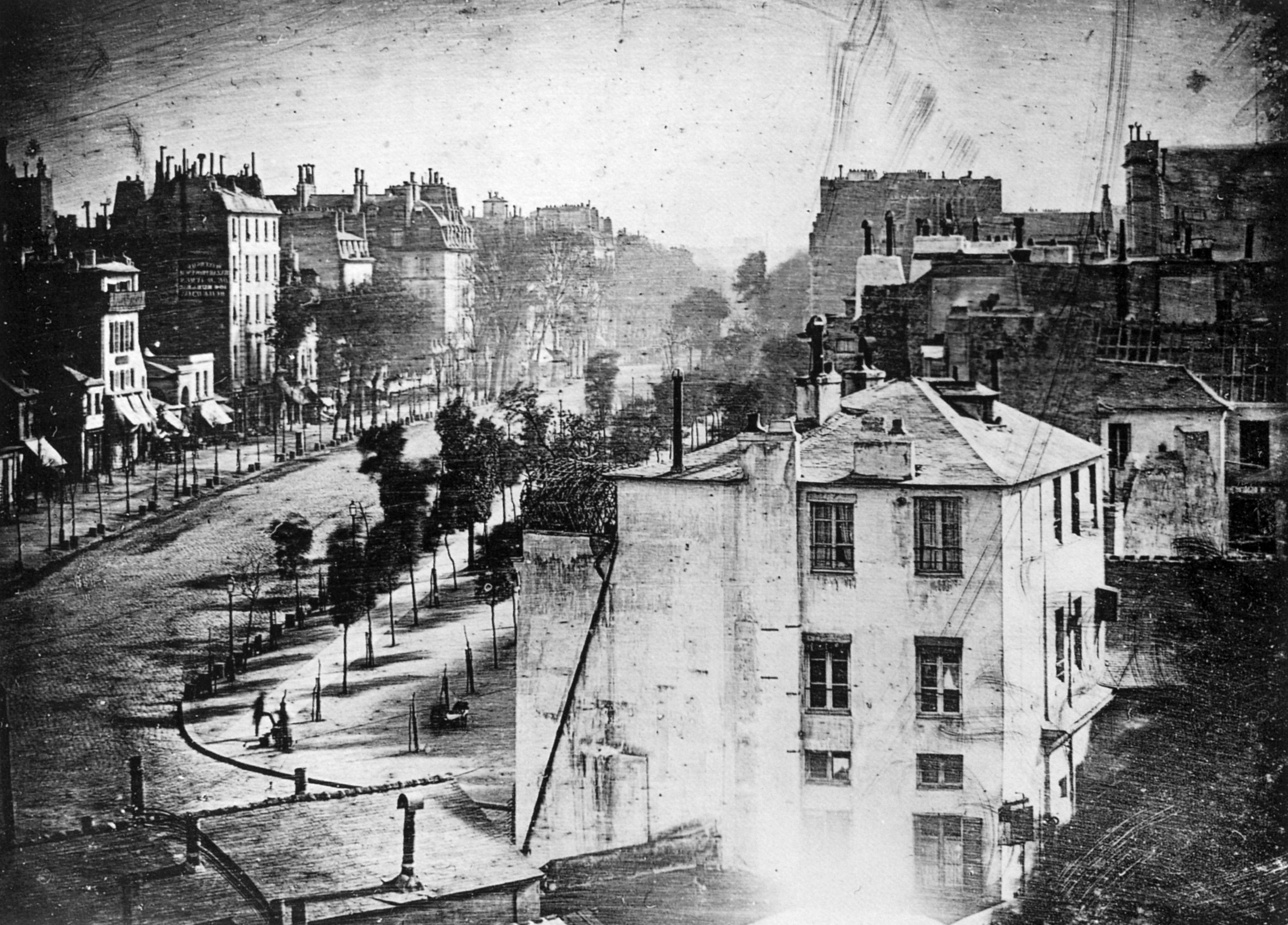

The explanation is that the first cameras were not like what you might be imagining. The machine they had brought was called a Daguerreotype, and it was indeed the very first type of photographic technology invented.

Photography is an obvious idea, but it is shockingly hard to implement.

First, you need a way to get the “image” to be projected on a surface. A minimum viable version of this is actually quite trivial; just poke a tiny hole in a box. Lenses help a lot, if you want to be picky about things like focal distance and controlling exposure.

But then, you just have some light on a surface. You can’t take that home and hang it on your bedroom wall. You need to cover the surface with some kind of substance that will change its own pigmentation based on how much light hits it. (Let’s not even talk about color photography.) This is a chemistry problem, which is why (film) photographers talk about “silver baths”.

Let’s say you’ve done that, and you have a nice little picture on a board. But now, as soon as you take it outside, it will get exposed to way more light all over, and the image will get destroyed. So after your chemical pigments change from the initial exposure, you have to do something to “fix” them, so they don’t change again. Now your choice chemicals has another major constraint. And you have to do this process before any more light gets on them, which is why photographers have to work in a “dark room”.

And then, hurray! You’ve got yourself a fine photograph. However, you have only one. You have no way of making a copy, unless you wanted to like, I dunno, take another picture of that picture, which would be wacky. The Daguerreotype had several other issues, which I’ll go into below.

So Stephens and Catherwood did take several Daguerreotype plates, but they then proceeded to “copy” them by making drawings, either back in their relatively hospitable tents or back in the States.[2]

Just barely better

This is a common pattern in the development and adoption of new technologies, which we are also seeing play out with deep learning.

A fundamentally new modality will often sound at first like it will produce a huge jump in capabilities. Examples, besides “a way to capture an image directly on a surface” and “a language program that passes the Turing test”, include “fireless light at the flick of a switch”, “putting speech onto a durable surface” and “making books with a machine that has little stamps for every letter”. Each of these sounds genius and obviously better, and it’s easy to imagine that if you went back in time you could be the person who Invents The Thing.

My impression however is that it would almost never be like that. Instead, each of these innovations was at first very costly and completely useless, then it was very costly and maybe useful, and only much later did it become invaluable and ubiquitous. Reasons for this rough transition could be split into two parts; the old way was better than you think, and the new way had heaps of problems.

The old way was better than you think

Catherwood’s manual illustrations were marvelous. Drawing gives the artist a lot of control. He had a wide variety of colors available. If he didn’t like how a line came out, he could erase it and try again.

When he was sketching, the sunlight was often harsh and uneven. Other times it was overcast or down-pouring. Regardless, he could use his mental understanding of what the scene looked like in 3D and across these conditions to combine them into one beautiful and comprehensible image.

Maya sculpture is especially elaborate and maximalist, and if one had just taken a quick snapshot of it, it would often look like a jumbled mess (especially since all the paint’s worn off). It’s often even hard to tell where, for example, the human figures are in the carving. Catherwood would take time to inspect the ruins and understand the artistic composition of them, which he would then use to subtly shade his illustrations in ways that made the composition clear to the viewer. As mentioned before, he could do this without sacrificing accuracy. Anyone who has tried to take a picture in a forest on a hike knows what I’m talking about. The view looks stunning, but somehow the picture just looks like random noise of leaves, with all the three dimensional structure flattened out.

In addition to all his classical training as an artist and in architectural drawings, Catherwood brought with him a device called a camera lucida. This was a clever prism setup by which the artist could look down onto the paper and see superimposed onto it an image of what was in front of them. This essentially allows one to “trace” the image, making it much easier to achieve consistent accuracy of position and proportions. This device is vastly simpler than a photographic camera.

The new way had heaps of problems

As described above, photography is fundamentally challenging because you need to project an image, capture it with a photosensitive substance, and the fix that substance to stop being photosensitive. Daguerreotypes achieved this, but they had many other issues.

The “black” part of the image was just the silver surface, so it didn’t look right unless you viewed it in the right lighting.

The image was extremely fragile. Anything brushing over it would remove the image. And silver tarnishes over time. So the plates had to be covered up with glass, and ideally sealed against the air.

There was no color.

As mentioned, there was no easy way to reproduce them. The invention of a photographic “negative” would have to wait.

Stephens and Catherwood had to spend a good deal of time learning how to use the device.

It was an extra object in their luggage, and a fragile one.

So when all was said and done, the outcome of their using the Daguerreotype was not noticeably better than without it. It perhaps saved them a bit of time and effort (though perhaps not).

There’s a similar story here with other innovations. Before the light bulb, kerosene lamps were impressively portable, stable, with adjustable brightness, and there was already a kerosene supply chain. Electric light bulbs were fragile, insanely hot, piercingly bright to look at, and required, you know, a source of electricity to operate. Written language was not very useful if you could just go tell the information to all 200 people in the village. What kind of information could there possibly be that couldn’t just tell someone? Societal knowledge could be passed down by telling your children. If it’s important enough to write down, they wouldn’t forget it anyway. And of course, you’d have to teach everyone how to read and write with this fancy new system. That would take years.

ChatGPT and other LLM tools

Disclaimer 2: My main point is in noticing how AI is fitting into a technological trend, and not that current AI is a certain amount of useful or useless.

My experience of trying to make use of current language models feels a lot like trying to use a Daguerreotype. I’m an early adopter, a former software engineer, and a lover of knowledge and information. So I use LLMs semi-regularly. But they’re not, like, useful for me yet. They’re a tool I keep trying because some day they will be useful, and I’d like to be there when that happens. And like, don’t get me wrong, that day could be next week. I have no idea how fast AI will move.

A lot of my experience has been realizing how effective the current systems are. Google search is unbelievably good at finding me the information I want.[3] Wikipedia has ungodly amounts of information in an extremely well-organized and vetted fashion. I have access to a mind-blowing number of books and research articles. And like, not joking, ctrl-f is OP.

Sometimes I want to know something more subjective, like “what do people generally think about X?” I would think LLMs would be better at this kind of summary, but they’re not. And I can often get this from sites with ratings, or forums like reddit, or (for my research) various stack exchange sites.

For other tasks, there are so many humans available that I could get to help me. The internet makes people available from across the world.

The old way is still really good.

Language models have heaps of problems. They still regularly hallucinate. They are comically sycophantic and seemingly unable to tell me which things are actually bad. They utilize huge amounts of energy compared to google search or asking a person.

I think the worst current thing about LLMs is that their answers are frequently highly plausible, but take a huge amount of time to verify or falsify. And half of the time when I do figure it out, the plausible answer was in fact wrong. So I just can’t make use of their plausible answers. It’s as if they’re perfectly calibrated to waste my time.

The future

Of course, ChatGPT is not as speculative as the Daguerreotype was. Hundreds of millions of people use LLMs on a regular basis. It’s not clear to me how much evidence this is for LLMs being genuinely useful, rather than being due to the nature of software and the internet (Wordle also had pretty fast adoption). People like to play with stuff. Many are happy to pay $20/month to get to play with the predecessor of what we know will be absolutely world-changing technology.

People were pretty psyched about the Daguerreotype; it was introduced in 1839, and Stephens and Catherwood were far from the first people to snag one in 1841. LLMs seem to clearly improve software engineering. Presumably Daguerreotypes had a small but immediately useful application.

We did figure out how to make cameras useful, and photography is ubiquitous. This is what will inevitably happen with AI, assuming it doesn’t kill us all first.

- ^

Everything I say in this post about the expeditions comes from this book, or rather, from my memory of what this book says. It’s quite well researched and cited, but I did not go back through it to check what I’m saying here, so I may be doing some unintended narrativization.

- ^

The original plates seem to have been later lost in a fire, which is why there are not even later photos of the plates. Reality has a surprising amount of detail.

- ^

Yeah, I agree that google search has been getting worst over the years. But it’s still incredible. Assuming, of course, that you ignore the AI result at the top. Did you know you can make that go away?

I really enjoyed the story of the Daguerreotype. However I would disagree that ChatGPT is currently at that state. I find it broadly useful for a bunch of tasks and have been making heavy use of it (and other LLMs) for years now. Starting with GPT 3.5 and onwards it seems to be more akin to modern photography than to the Daguerreotype.

Edit: Since I have gotten quite a few disagreements, I would like to know why. Firing of a quick question and asking a follow up is so much faster than googling or using wikipedia / combing through reddit threads most of the time. Also its an amazing learning partner, when you want to dabble with something that you have little expertise in. Of course its not perfect, but it seems clearly not in the “We have not yet figured out how to make LLMs useful” state.

I really like the interesting context you provide via storytelling about the use of daguerrotypes by historical explorers, and making the connection to LLMs.

When I think about how the daguerrotype fits into a technological arc, I view it as:

An interesting first version of a consumer technology, but also

Something that was quite comedically fundamentally flawed — imagining an explorer arduously grappling with sheets of polished silver to get a grainy, monochrome sketch of their vivid endeavours is quite amusing

I think your comparison to LLMs holds well for 1), but is less compelling for 2). I know you state a disclaimer of not making a comment about “certain amount of useful or useless” but you do talk about how useful LLMs are for you, and I think it is relevant to make a comparison.

As you point out hundreds of millions of people use ChatGPT — 1 million used it in the first 5 days of release, and OpenAI anticipate 1 billion users by the end of 2025. This does imply ease of use and good product-world fit.

You state:

but we already know that given an individual statement LLMs are highly capable of text classification — extending this for Reddit-style consensus feels like a relatively small engineering change versus a daguerrotype-to-camera type jump.

LLMs do have some funny flaws, like hallucination and sycophancy, but personally I can’t map these to be comparable to the daguerrotype and I speculate that ChatGPT will be viewed less like a “comedically flawed first try at the future thing” (like daguerrotype-camera) and more like a “promising first version of the future thing” (like typewriter-digital word processor).