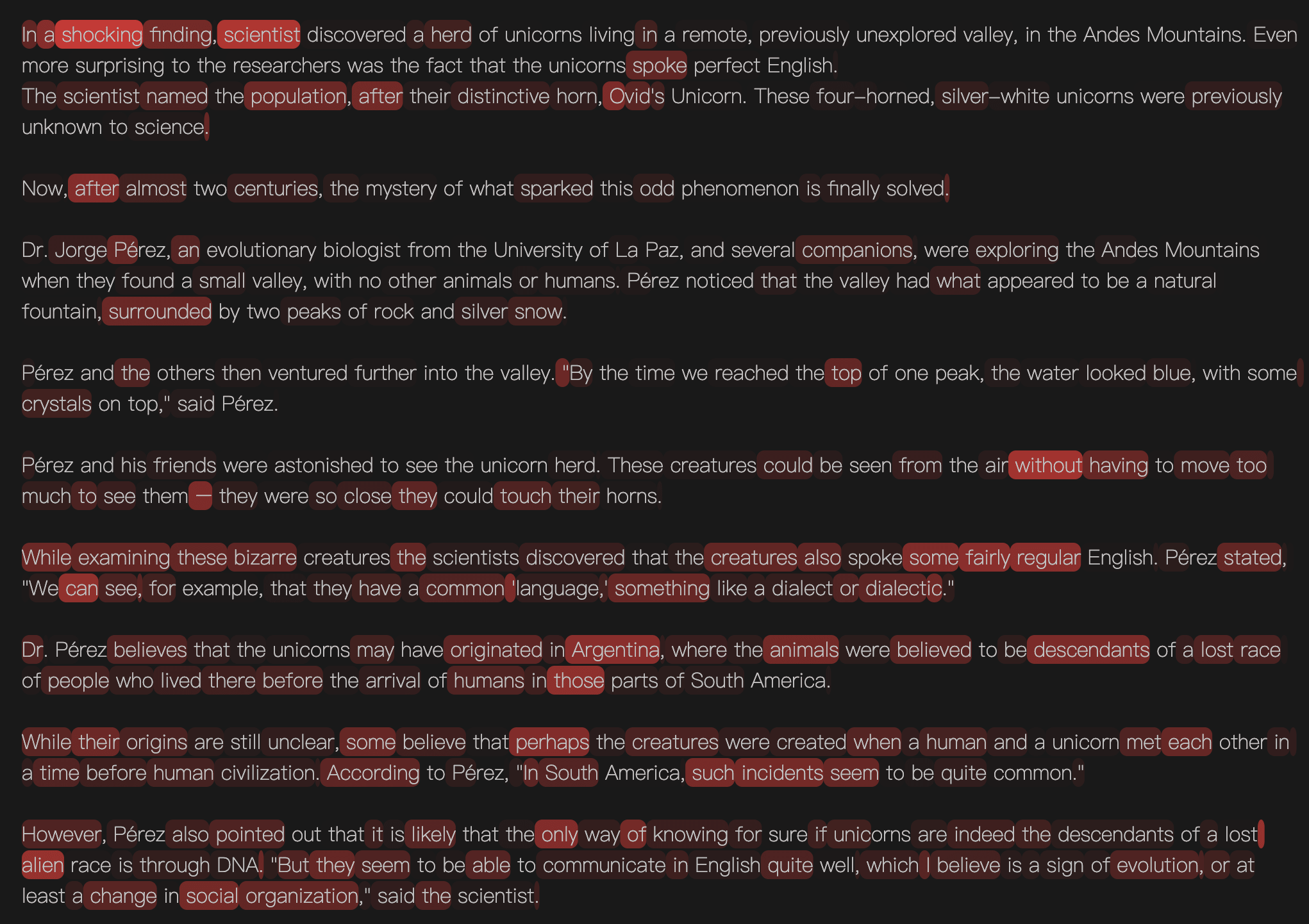

Word importance in text ⇐ conditional information of the token in the context. Is this assumption valid?

Words that are harder to predict from context typically carry more information(or surprisal). Does more information/surprisal means more importance, given everything else the same(correctness/plausibility, etc.)?

A simple example: “This morning I opened the door and saw a ‘UFO’.” vs “This morning I opened the door and saw a ‘cat’.” — clearly “UFO” carries more information.

‘UFO’ seems more important here. But is this because it carries more information? This topic may be around the information-theoretic nature of language.

If this is true, it’s simple and helpful to analyze text information density with large language models and visualizes where the important parts are.

It is a world of information, layered above the physical world. When we read text we are intaking information from a token stream and get various information density across that stream. Just like when we recieve things we get different “worth”.

------

Theoretical Timeline

In 1940s: The foundational Shannon Information Theory.

Around 2000, key ideas point toward a regularity in the information-theoretic nature of language:

Entropy Rate Constancy (ERC) hypothesis: Word’s absolute entropy increases with position, thus conditional entropy stays roughly constant across the text.

Uniform Information Density (UID) hypothesis: Humans tend to distribute information as evenly as possible across the text — a kind of “information smoothing pressure” that releases info gradually).

Surprisal Theory: Surprisal correlates almost linearly with reading times / processing difficulty.

Now, LLMs come out. LLMs x information theory — what kind of cognitive breakthrough might this bring to linguistics?

At least right now, one thing I can speculate is: Shannon information seems to represent the upper bound on “importance.”

Are we on the eve of re-understanding the information-theoretic nature of language?

More potential importance. Consider high entropy clauses ranging from total gibberish or jargon which, aside from revealing some information about the author/narrator, doesn’t substantially change the content communicated:

This sounds incredible at first, but the underwhelming context is that they have named their domestic cat “Aslan”. Is it important to know that the narrator knows the cat on a first name basis, and that this cat (who may or may not be owned by the narrator) is owned by someone with a sense of humor, a taste for ironic ‘antonomasia’ who has at the very least watched the Chronicle of Narnia films?

Not all surprising parts of a sentence are important.

You might also be interested in James Pennebaker research into function words—this doesn’t apply to LLMs I would assume—but he found that doing statistical analysis on the seemingly least important words in English: couplas, pronouns etc. etc. they could predict the amount of medical visits of students. When you remember that the most commonly used, and therefore functional words, tend to be the shortest in a language following a Zipf Law: I, we, of, to, the, yes, no… this makes sense. What Pennebaker’s research has revealed is that even these choices can reveal a lot about the status and mental health of the author.

More potential importance

<-> Not all surprising parts of a sentence are important.

<-> All important parts must be surprising.

<-> Word importance in text ⇐ conditional information of the token in the context.

Thank you again! You help me see it more clear!

Thanks. You are right. I need to add an assumption, “given everything else the same”. We need to exclude surprise changes caused by variations in correctness/plausibility. Correctness/plausibility can be relatively easily distinguished through other methods. And I just added some content to the article, including: “At least right now, one thing I can speculate is: Shannon information seems to represent the upper bound on ‘importance.’”

About the “Aslan” example: the high “information” it carrays is reasonable, since the explanation following is quite “informational” for those who are interested. After the “upper bound” addtion, this example becomes reasonable, right? :)

About the “James Pennebaker research” example, I will understand it in this way: of the seemingly least important words, each one carrays a little bit information about the status and mental health of the author. The researcher collect those bits of information and make use of it. As long as “information/surprisal” is precise enough(LLMs are good at it, and fast growing), these applications would be all reasonable from information-theoretic view.

Hope it makes sense to you :)